Abstract

Overlapping of left ventricular noncompaction (LVNC) and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in the same patient is rare and is associated with a more severe clinical course and unfavorable prognosis. The present report describes the case of a severely regurgitant bicuspid aortic valve in a 68-year-old man with overlapping LVNC and asymmetrical septal hypertrophy. Aortic valve replacement controlled the left ventricular dilatation that occurred secondary to the volume overload induced by the valvular disease. However, even 3 years postoperatively, severe systolic dysfunction persisted due to the preexisting myocardial disease, requiring close and lifelong follow-up with special attention to life-threatening arrhythmias and thromboembolism.

Keywords: Aortic valve replacement, asymmetrical septal hypertrophy, bicuspid aortic valve, left ventricular noncompaction

INTRODUCTION

Left ventricular noncompaction (LVNC) is believed to result from arrest of endomyocardial development in early embryogenesis and is no longer considered a rare cardiomyopathy. Since the clinical course of LVNC in adults is highly variable, ranging from asymptomatic to debilitating heart failure or even life-threatening arrhythmia and sudden death, the prognosis is still unclear.[1] Although reports documenting the combination of LVNC and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) are scarce, the overlapping cardiomyopathy is associated with a more severe clinical course with unfavorable cardiovascular complications, including atrial fibrillation, ventricular tachycardia, and thromboembolism.[2] We present a rare case of a severely regurgitant bicuspid aortic valve (BAV) complicating overlapping LVNC and asymmetrical septal hypertrophy.

CASE REPORT

A 68-year-old man was admitted with progressive heart failure and a brain natriuretic peptide level of >2000 pg/ml despite long-term appropriate medical management. The patient had been diagnosed with HCM at the age of 40 years. At 58 years of age, during admission for deterioration of heart failure that required respiratory management, overlapping LVNC and HCM was diagnosed by echocardiography and left ventriculography [Figure 1 and Video 1]. Coronary angiography noted no significant lesions. Thereafter, he experienced recurrent deterioration of chronic heart failure. He had a family history of cardiac diseases, although the details were unknown.

Figure 1.

Left ventriculography showing the noncompacted myocardium (arrow) [Video 1]

At admission, transthoracic echocardiography showed asymmetrical septal hypertrophy with a maximum wall thickness of 23 mm. Additionally, excessive trabeculation with deep intertrabecular recesses were observed at the apex, lateral and posterior aspects of the left ventricular (LV) wall [Figure 2a]. The ratio between the noncompacted and compacted layers was approximately 2.0–2.5, and color Doppler flow into the intertrabecular recesses from the LV cavity [Figure 2b and Video 2] fulfilled the diagnostic criteria for LVNC. Further, color Doppler echocardiography demonstrated severe aortic regurgitation with a BAV. His LV ejection fraction was reduced to 38% with diffuse LV hypokinesis, and the LV end-diastolic and end-systolic diameters were 77 mm and 62 mm, respectively. We considered that aortic valve replacement (AVR) was required for partial management of chronic heart failure.

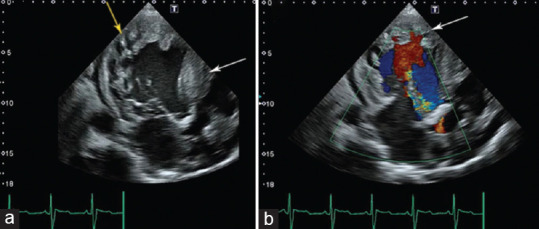

Figure 2.

(a) Transesophageal echocardiography demonstrating the noncompacted myocardium (yellow arrow) and asymmetrical septal hypertrophy (white arrow), (b) Color Doppler echocardiography demonstrating color Doppler blood flow into the intertrabecular recesses (arrow) [Video 2]

Through median sternotomy, the markedly dilated left ventricle was confirmed [Figure 3a and Video 3]. The patient underwent AVR with a 23-mm Inspiris Resilia aortic bioprosthesis (Edwards Lifesciences, LLC, Irvine, CA, USA). The excised native aortic valve was a moderately calcified bicuspid type 1 aortic valve with right-noncoronary cusp fusion [Figure 3b]. The patient’s postoperative course was complicated by the transient need for hemodialysis due to chronic renal failure, ischemic colitis, and long-term respiratory management. The patient was also defibrillated three times for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation with hemodynamic instability despite the use of amiodarone.

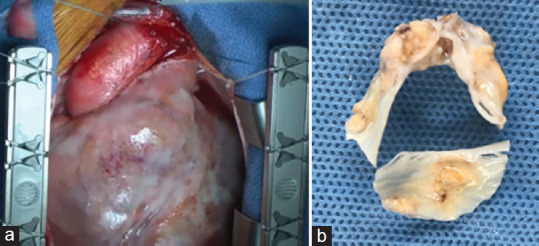

Figure 3.

(a) Intraoperative view of the enlarged left ventricle [Video 3], (b) Moderately calcified bicuspid aortic valve with right-noncoronary cusp fusion

Postoperative echocardiography 3 years after the surgery revealed no improvement of systolic function, with an LV ejection fraction of 22%. However, his LV end-diastolic and end-systolic diameters had decreased to 61 mm and 55 mm, respectively, along with a decrease of his left atrial diameter from 49 to 43 mm. At present, the patient has survived without further hospitalization for worsening heart failure. However, laboratory examinations still reveal an elevated brain natriuretic peptide level of 1243 pg/ml, and the patient continues to take beta-blocker agents and anticoagulant therapy with warfarin to prevent life-threatening arrhythmias and thromboembolism.

DISCUSSION

With the advances in and spread of diagnostic modalities, several cases with rare overlapping phenotypes of LVNC and HCM have been reported in recent years.[3,4] Among modalities, cardiac magnetic resonance is playing an increasing role in cardiomyopathy, providing phenotypes associated with cardiomyopathy that are missed by echocardiography and better characterizing cardiac morphology of the rare overlapping phenotype.[3,5] Although the genotype–phenotype relationship between these diseases still remains unclear, the overlapping disease is documented to be associated with a high risk of cardiovascular complications and a more severe clinical course.[2] In our case as well, the patient experienced long-term recurrent heart failure requiring transient ventilatory management and a complicated and eventful perioperative course following AVR.

The association between BAV and LVNC has been presented in the literature. Jeong et al. reported that concomitant LVNC was the most prevalent; however, its prevalence in BAV subjects was only 3.4%. In addition, the authors reported that the presence of concomitant cardiomyopathy was independently associated with heart failure in patients with BAV.[6] Recently, BAV research focuses not only on the valve itself but also on its relationship to the left ventricle and aorta. In our case, because the aortic arch was similar in shape to a triangle, the gothic aortic arch was suspected [Figure 3 and Video 3]. Pergola et al. suggested that an increased shear stress due to the gothic aortic arch in certain regions of the aorta can trigger pathological remodeling processes, including arterial stiffness, endothelial dysfunction, and vascular remodeling. Furthermore, the gothic aortic arch anomaly can influence ventricular–vascular interactions, particularly regarding ventricular load and contractility.[7] These changes may be related to the LVNC trigger as a contributing factor.

Several surgical cases of BAVs in patients with LVNC have been previously reported. In most of these cases, there were no complications, and improvement in cardiac function was achieved.[8,9,10] In the present case, systolic function did not improve, although echocardiography demonstrated a reduction in LV and atrial diameters 3 years postoperatively. LVNC has a wider spectrum of disease progression, from a more severe prognosis to a more stable course. The prognosis for symptomatic LVNC patients with LV systolic dysfunction is even worse, especially when the clinical manifestations are extensive, like our case. However, AVR controlled the exacerbation of heart failure that occurred due to the volume overload induced by preexisting myocardial disease.[9,10] Comorbid valve surgery in adults with overlapping LVNC and HCM is extremely rare. Given the natural prognosis of overlapping cardiomyopathy reported in several papers, the postoperative recovery of systolic function is likely to be strongly affected by the gravity of the preexisting myocardial disease. Given our case, the presence of LVNC does not preclude surgical repair for cardiac abnormalities particularly if they contribute to a decline in the patient’s condition.

In summary, we experienced a rare case of a severely regurgitant BAV complicating overlapping LVNC and asymmetrical septal hypertrophy. AVR successfully controlled the LV dilatation due to volume overload secondary to the comorbid valve disease. However, severe systolic dysfunction due to the preexisting overlapping myocardial disease still persisted, requiring close lifelong follow-up, with special attention to life-threatening arrhythmias and thromboembolism.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Videos Available on: https://journals.lww.com/JCEG

REFERENCES

- 1.Parekh JD, Iguidbashian J, Kukrety S, Guerins K, Millner PG, Andukuri V. A rare case of isolated left ventricular non-compaction in an elderly patient. Cureus. 2018;10:e2886. doi: 10.7759/cureus.2886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Komissarova SM, Rineiska NM, Chakova NN, Niyazova SS. Overlapping phenotype:Left ventricular non-compaction and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Kardiologiia. 2020;60:137–45. doi: 10.18087/cardio.2020.4.n728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gonçalves L, Pires I, Santos J, Correia J, Neto V, Moreira D, et al. One genotype, two phenotype:Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with left ventricular non-compaction. Cardiol J. 2022;29:366–7. doi: 10.5603/CJ.2022.0020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kastelic U, Parameswaran AC, Cheong BY. A rare combination of two rare diseases:Left ventricular noncompaction and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:e37. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.03.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kelley-Hedgepeth A, Towbin JA, Maron MS. Images in cardiovascular medicine. Overlapping phenotypes:Left ventricular noncompaction and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2009;119:e588–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.829564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jeong H, Shim CY, Kim D, Choi JY, Choi KU, Lee SY, et al. Prevalence, characteristics, and clinical significance of concomitant cardiomyopathies in subjects with bicuspid aortic valves. Yonsei Med J. 2019;60:816–23. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2019.60.9.816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pergola V, Avesani M, Reffo E, Da Pozzo S, Cavaliere A, Padalino M, et al. Unveiling the gothic aortic arch and cardiac mechanics:Insights from young patients after arterial switch operation for d-transposition of the great arteries. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis. 2023;94 doi: 10.4081/monaldi.2023.2712. [doi:10.4081/monaldi.2023.2712] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hajj-Chahine J, Allain G, Tomasi J, Jayle C, Corbi P. Aortic root replacement in a patient with left ventricular noncompaction. Ann Thorac Surg. 2014;97:e1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wrigley BJ, Rosin M, Banerjee P. Replacement of a congenital bicuspid aortic valve in a patient with left ventricular noncompaction. Tex Heart Inst J. 2009;36:241–3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilbring M, Kappert U, Schön S, Tugtekin SM, Geiger K, Alexiou K, et al. Aortic valve replacement in noncompaction cardiomyopathy at two-year follow-up. J Card Surg. 2009;24:684–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8191.2009.00916.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.