Abstract

Introduction

Warts are the most prevalent clinical manifestation of Human Papilloma Virus (HPV) infections, which vary in morphological pattern depending on the site of the body affected.

Objectives

To evaluate the safety and efficacy of intralesional quadrivalent HPV vaccine versus candida antigen in treatment of multiple recalcitrant non-genital warts.

Methods

A randomized-control clinical trial included 60 cases with multiple recalcitrant warts who were randomly distributed into three groups; Group I included 20 patients who received intralesional candida antigen at a dose of 0.3 mL of 1/1000 solution, Group II included 20 patients who received intralesional quadrivalent HPV vaccine at a dose of 0.3ml and Group III included 20 patients who received intralesional injection 0.3 ml of normal saline 0.9% as a control group). Each agent was injected at the base of the largest wart every three weeks until it was completely cleared, or for a total of four sessions.

Results

the highest response rate was detected in the quadrivalent HPV vaccine group (75% complete response) followed by the candida vaccine group (40% complete response and 15% partial response). Also, regarding the distant response rate, the highest response rate was detected in the quadrivalent HPV vaccine group (72.7% complete response and 27.3% partial response) followed by the candida vaccine group (33.3% complete response and 50% partial response).

Conclusions

Intralesional immunotherapy appears to be effective and safe in treating multiple recalcitrant non-genital warts, with intralesional quadrivalent HPV vaccine outperforming intralesional candida antigen.

Keywords: warts, non-genital, recalcitrant, human papillomavirus vaccine, candida antigen

Introduction

Warts are benign epithelial proliferations resulting from more than 200 serotypes of Human Papilloma Virus (HPV) infection occurring on the skin and mucosa [1]. Warts are not life-threatening or harmful, but they can be embarrassing to the patient when present in the exposed areas of the body. Warts are infectious and can spread by skin-to-skin contact. However, the strains vary in their intensity of contagiousness [2].

Warts are categorized into two types: cutaneous and extracutaneous. Common warts, filiform warts, planter warts, plane warts, anogenital warts are among the cutaneous lesions. Oral common warts, oral condylomata acuminata, focal epithelial hyperplasia, oral florid papillomatosis, nasal papillomas, conjunctival papillomas, laryngeal papillomatosis, and cervical warts are extracutaneous lesions that affect the mucous membranes [3].

Unfortunately, a specific antiviral agent against HPV is lacking and while most warts spontaneously disappear, some persist and are resistant to treatment. All available treatment modalities intend to destroy lesions by chemical agents such as salicylic acid, 5-fluorouracil, and/or by physical destructive methods; eg (electrocautery, cryotherapy, photodynamic therapy and surgical excision). These methods, however might be associated with scarring, pain and high rates recurrence [4–6].

Intralesional antigen immunotherapy represents a promising therapeutic approach for the treatment of different types of warts, particularly if multiple and/or recalcitrant. Immunotherapeutic approaches act by enhancing the host cell-mediated immunity to eliminate the virus rather than just clearing the skin lesions [7].

The efficacy of immunotherapy using a single test antigen and multiple test antigens in the treatment of warts has been investigated with various degrees of success. Tuberculin purified protein derivative (PPD), measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine, mycobacterium w vaccine, interferon-α or β, Candida antigen, and Bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG) vaccine are a few examples of immunotherapeutic drugs that have been researched [8–10] The efficacy of Candida skin-test antigen in wart resolution was demonstrated in the first such trial [11].

Several studies have confirmed the role of a prophylactic quadrivalent HPV vaccine (HPV types 6, 11, 16, and 18) in the prevention of HPV-associated precancerous and cancerous lesions. There might be some cross-reactivity of antigenic epitopes in the HPV types covered by the vaccine and other HPV types responsible for common warts [12–14].

Objectives

In this study we aimed to evaluate and compare the safety and efficacy of intralesional Candida antigen versus quadrivalent HPV vaccine in treatment of multiple recalcitrant non-genital warts.

Methods

Patients

This is a three arm, single blinded, randomized controlled clinical trial included 60 cases.

Inclusion Criteria

patients who have multiple recalcitrant non-genital warts.

Recalcitrant warts were defined as warts that persisted for more than one year and were resistant to at least two therapeutic modalities.

Exclusion Criteria

patients on any treatment modality for warts during the last month prior to enrollment, pregnant and lactating females; patients with known hypersensitivity to Candida albicans antigen, with acute febrile illness, autoimmune disease or immunodeficiency were excluded from the study.

Assessments

All patients enrolled in the study were subjected to full history taking, general and dermatological examination to determine number, site, and size of warts and to detect presence or absence of distant warts or other skin diseases. Digital photography was done for all patients at baseline, follow up visits and after completion of treatment sessions.

Patients were randomly distributed into three equal groups:

Group I included 20 patients who received intralesional candida antigen at a dose of 0.3 mL of 1/1000 solution.

Group II included 20 patients who received intralesional quadrivalent HPV vaccine at a dose of 0.3ml.

Group III included 20 patients who received intralesional injection 0.3 ml of normal saline 0.9% as a control group). Following the study completion, these patients were treated.

Each agent was injected every three weeks at the base of the largest wart until it was entirely removed or for a maximum of four sessions. The study was approved by an Ethics Committee of Damietta Faculty of Medicine IRB (00012367-20-12-004), Al-Azhar University, Egypt. Written informed consent was obtained from adult patients and parents of children included into the study.

Evaluation of the Clinical Response

The evaluation of therapeutic response was carried out by evaluating the size and counting the number of injected and distant warts by digital photographic comparison at baseline and at each visit. Complete response (disappearance of the warts and appearance of normal skin), partial response (50%–99% reduction in size) and no response (0%–49% reduction in size). Patients were examined and asked to report any local adverse effects such as erythema, pain, edema, hypopigmentation and hyperpigmentation, as well as systemic side effects like fever, myalgia, headache, and vomiting.

Follow-up

A 6-month follow-up assessment was performed every month after the therapy was completed to detect any recurrence of warts.

Statistical Analysis

The data collected were coded, processed and analyzed with SPSS version 27 for Windows® (Statistical Package for Social Sciences) (IBM, SPSS Inc). Qualitative data as number (frequency) and percent was presented. The Chi-Square test (or Monte-Carlo test) made the comparison between groups.

The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test tested quantitative data for normality. Parametric data were expressed as median ± SD while the non-parametric data were expressed as median (Range). To compare three groups with normally distributed quantitative variables, one-way analysis of the variance (one-way ANOVA) test was used and Kruskal-Wallis test was used if the data were abnormally distributed. For all tests, P values <0.05 are considered significant.

Results

The study included 60 patients with multiple non-genital warts. The median age in group I was 16 years with range between 10 and 39 years, the median age in group II was 14 years with range between 9 and 34 years and the median age in group III was 20 years with range between 10 and 38 years. There was no statistically significant difference between the cases in the different studied groups regarding the age (P = 0.114).

As regards to the sex, there were 40% males and 60% females in group I, there were 35% males and 65% females in group II and there were 25% males and 75% females in group III with no statistically significant difference between the studied groups regarding the sex distribution (P = 0.293).

In regard to type of warts, in group I, the most common type of wart was common warts in 80% of the cases followed by plantar wart in 20% with no cases with plane warts in this group. In group II, the most common type of wart was common warts in 60% of the cases followed by plantar wart in 30% and plane warts in 10% of the cases. In group III, the most common type of wart was plantar warts in 85% of the cases followed by common wart in 15% with no cases with plane warts in this group.

As regards to number of warts, the median number of warts in group I was 3 with range between 3 and 13, the median number of warts in group II was 4 with range between 3 and 12 and the median number of warts in group III was 3 with range between 3 and 7. There was no statistically significant difference between the cases in the different studied groups regarding the number of warts (P = 0.282).

The median disease duration in group I was 20 months with range between 18 and 24 months, the median disease duration in group II was 24 months with range between 18 and 28 months and the median disease duration in group III was 20 months with range between 12 and 24 months. There was no statistically significant difference between the cases in the different studied groups regarding the disease duration (P = 0.059).

Presence of distant warts was reported in 30%, 55% and 15% in group I, II and III respectively with statistically significant difference between the studied groups (P = 0.025, Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the studied patients

| Variable | Group I Candida antigen (N = 20) | Group II Quadrivalent HPV vaccine (N = 20) | Group III Normal saline (N = 20) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||

| Males | 8 (40%) | 7 (35%) | 5 (25%) | 0.293 |

| Females | 12 (60%) | 13 (65%) | 15 (75%) | |

| Age (years) | 16 (10–39) | 14 (9–34) | 20 (10–38) | 0.114 |

| Number of warts | ||||

| Median (Range) | 3 (3–13) | 4 (3–12) | 3 (3–7) | 0.282 |

| Duration of warts (Months) | ||||

| Median (Range) | 20 (18–24) | 24 (18–28) | 20 (12–24) | 0.059 |

| Distant warts | 6 (30%) | 11 (55%) | 3 (15%) | 0.025 |

| Type of warts | ||||

| Common warts | 16 (80%) | 12 (60%) | 3 (15%) | < 0.001 |

| Plantar warts | 4 (20%) | 6 (30 %) | 17 (85%) | |

| plane wart | 0 (0%) | 2 (10%) | 0 (0%) | 0.468 |

| Distant warts | ||||

| 6(30%) | 11 (55%) | 3 (15%) | 0.025 | |

| Previous treatment | ||||

| Cryotherapy | 17 (85%) | 18 (90%) | 20 (100%) | 0.236 |

| Salicylic acid | 19 (95%) | 16 (80%) | 18 (90%) | |

| Laser | 1 (5%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Topical retinoid | 0 (0%) | 1 (5%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Electrotherapy | 1 (5%) | 2 (10%) | 2 (10%) | |

| MMR intralesional injection | 0 (0%) | 1 (5%) | 0 (0%) | |

HPV = Human Papilloma Virus.

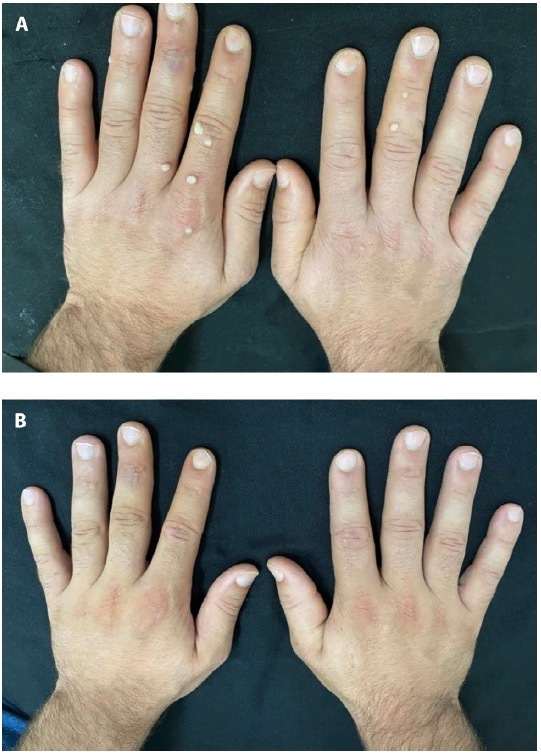

Figure 1.

Male patient 21-year-old with multiple common warts on both hands (A) before, (B) after treatment with intralesional candida antigen.

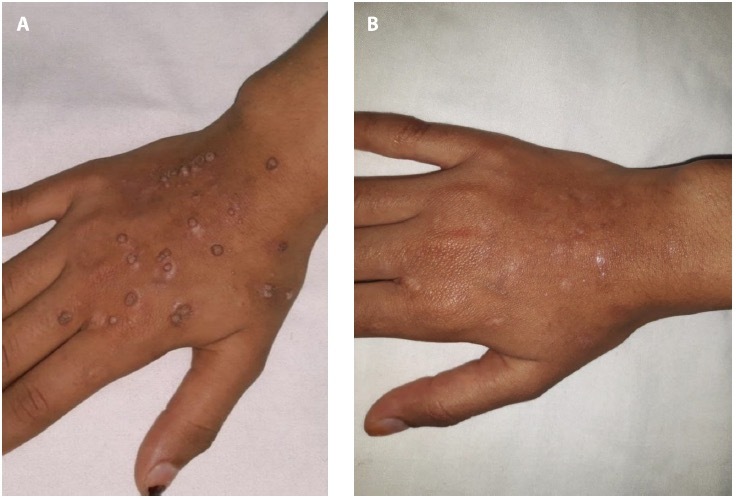

Figure 2.

Female patient 15-year-old with multiple common warts on the right hand (A) before, (B) after treatment with intralesional quad-rivalent HPV vaccine.

Regarding the therapeutic response within the three studied groups, in group I, complete response was reported in (40%) of the cases, partial response in (15%) and no response in (45%). In group II, complete response was detected (75%) of the cases and no response in (25%). In group III, partial response in (10%) of the cases and no response in (90%) there was a statistically significant difference as regarding the local response between the three studied groups with the highest response in group II (quadrivalent HPV vaccine) followed by group I (Candida antigen).

Regarding the response in the distant warts within the three studied groups, in group I, complete response was detected in 2 out of 6 patients (33.3%), partial response in 3 out of 6 patients (50%) and no response in 1 out of 6 patients (16.7%). In group II, complete response was detected in 8 out of 11 patients (72.7%) and partial response in 3 out of 11 patients (27.3%). In group III, no distant partial or complete local response was detected. There was a statistically significant difference as regarding the response between the three studied groups with the highest response in group II (quadrivalent HPV vaccine) followed by group I (Candida antigen, Table 2).

Table 2.

Therapeutic response among the studied patients

| Variable | Group I Candida antigen (N = 20) | Group II Quadrivalent HPV vaccine (N = 20) | Group III Normal saline (N = 20) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complete response | 8 (40%) | 15 (75%) | 0 (0%) | < 0.001 |

| Partial response | 3 (15%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (10%) | |

| No response | 9 (45%) | 5 (25%) | 18 (90%) | |

| Distant response | ||||

| Group I Candida antigen (N = 6) | Group II Quadrivalent HPV vaccine (N = 11) | Group III Normal saline (N = 3) | ||

| Complete response | 2 (33 %) | 8 (72.7 %) | 0 (0%) | 0.002 |

| Partial response | 3 (50 %) | 3 (27.3 %) | 0 (0%) | |

| No response | 1 (16%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (100 %) | |

HPV = Human Papilloma Virus.

Regarding the local side effects, tolerable pain during injection was reported in all the included cases. In group I, other local side effects included erythema in 30%, swelling in 30% and tenderness in 15% of the cases while in group II, erythema was detected in 25% of the cases.

Regarding the distant side effects, fever was detected in 55% and 10% in group I and group II respectively while bone ache was reported in 15% of the cases in group I only (Table 3).

Table 3.

Local and distant side effects among the studied patients

| Variable | Group I Candida antigen (N = 20) | Group II Quadrivalent HPV vaccine (N = 20) | Group III Normal saline (N = 20) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Local side effects | ||||

| Tolerable pain during injection | 20 (100%) | 20 (100%) | 20 (100%) | 0.011* |

| Erythema | 6 (30%) | 5 (25%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Swelling | 6 (30%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Tenderness | 3 (15%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Distant side effects | ||||

| No distant lesions | 9 (45%) | 18 (90%) | 20 (100%) | < 0.001* |

| Fever | 11 (55%) | 2 (10%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Bone ache | 3 (15%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

HPV = Human Papilloma Virus.

No statistically significant difference in the adverse effects was observed between all studied groups.

No recurrence of warts was reported during the 6-month follow-up period in both groups.

Conclusions

In general, practice, non-genital warts are a common. Despite following evidence-based treatment guidelines, a significant percentage of warts do not cure and become recalcitrant.

This current study was conducted to evaluate the efficacy of intralesional quadrivalent human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine versus Candida antigen in treatment of multiple recalcitrant non-genital Warts.

The current study included 60 cases with multiple recalcitrant non-genital warts who were randomly distributed according to the treatment regimen into three groups; group I that included cases who received intralesional treatment with candida antigen, group II that included cases received intralesional treatment with quadrivalent HPV vaccine and group III that included cases received normal saline as a control group.

In the current study, the incidence of complete response after intralesional candida antigen was 40% and after intralesional injection of quadrivalent HPV vaccine was 75% with no cases with complete response in the control group. Also, partial response was noticed in 15% and 20% in the candida antigen group and control group respectively.

The rate of response to candida antigen was similar to an Egyptian study conducted by Marei et al who showed that 58.3% of studied patients showed complete response [15].

However, although Nassar and her colleagues showed superiority of both candida antigen and HPV vaccine over control, the rate of response was different form our study. In their study, complete clearance of warts was reported in 63.3% of the Candida antigen group, 50% of the bivalent HPV vaccine group and 0% of the control group. A statistically significant difference in the therapeutic responses was found between the treatment and control groups and between both the Candida anti-gen and bivalent HPV vaccine.

The difference between the Candida antigen and bivalent HPV vaccine groups was statistically insignificant [16]. The difference between our study and this study may be explained by the differences in the nature of the treated warts (recalcitrant in our study). Also, the previous study used bivalent vaccine and our study used quadrivalent vaccine that provide greater cross-protection against HPV strains than provided by bivalent vaccine.

The rate of response in the candida antigen group was similar to many other studies including Signore (51%), Clifton et al (47%), Horn et al (54%), King et al (50%), Majid and Imran (56%), Alikhan et al (39%), and Nofal et al. (33.3%) [17–23].

An earlier study has shown higher response rate. Johnson et al showed 74% complete clearance of wart among studied group [24].

The disparities in the success rates between our study and the other related studies might be attributed to factors related to differences in the nature of the treated warts (multiple recalcitrant in our study), degree of HPV resistance and different HPV serotypes, and the number of the studied patients. Also, different injection regimens regarding the manufacturer of the antigen, the amount and concentration of the injected antigen per session, the number of the treatment sessions and the interval between the sessions

Candida antigen works primarily by inducing Th1 cytokines including IFN- and IL-2, which stimulate cytotoxic and natural killer cells to eliminate HPV infection not only at the injection site but also at nearby and distant non-injected sites Nofal et al [25].

In the current study, regarding the distant response rate, the highest response rate was detected in the HPV vaccine group followed by the candida antigen group. In the candida antigen group, complete response was detected in 33.3% and partial response in 50% while in the quadrivalent HPV vaccine group, complete response was detected in 72.7% and partial response in 27.3%.

This disagreed with Nassar et al who showed that the rate of resolution of distant, non-injected warts was 71.4% in the Candida group versus 41.2% in the HPV vaccine group [16].

The difference could be explained due to that the previous study used bivalent vaccine and our study used quadrivalent vaccine that provide greater cross-protection against HPV strains than provided by bivalent vaccine.

The mechanism of action of HPV vaccines in the treatment of warts is not yet established. This might be mediated by the development of IgG neutralizing antibodies directed against HPV-L1 capsid proteins generated as a result of vaccination. Although the HPV strains that cause common warts may be less genetically related to those implicated in cervical, vulvar, and anal cancer, it has been previously postulated that HPV vaccines can provide cross-protection against HPV strains other than those targeted by the individual vaccine administered [26,27].

The combination of drugs, with different mechanisms of action, has been postulated to improve treatment response, decrease adverse effects, and minimize recurrence rate. Many authors have reported better control of HPV infections using combined therapeutic modalities compared with monotherapy in the treatment of warts, particularly the recalcitrant ones [25,28].

One of the advantages of HPV vaccines is that the VLPs are not infectious, since they lack the virus DNA. Therefore, they can be used safely in case of immunosuppression, a major obstacle for other types of immunotherapies. Furthermore, the development of HPV-directed immunity after receiving the vaccine has a double benefit in the treatment of current infection and the prevention of future one [29].

In the current study, in the control group who received intralesional saline, local partial response was achieved in 10% of the cases with no distant response.

Fathy and his colleagues reported that intralesional injection of saline was associated with 20.7% good response and 79.3% poor response after the 5th session in cases with planter warts with no complete clearance of any wart [30].

Also, Mohamed and his colleagues reported a statistically significant decrease in the number of warts after 5 sessions of injection of intralesional saline of warts. The mechanism of action of intralesional saline is unknown; it may be due to exposure of the viral particles to the immune system that later attacks them through the trauma produced during the injection [31].

The difference between our study and these studies may be explained by the differences in the nature of the treated warts (recalcitrant in our study) as the duration of the warts show a significant inverse correlation with the treatment response (the longer the duration, the lower the response). Also the number of the treatment sessions (5 sessions versus 3 sessions in our study).

The main strength point of the current study, the first to evaluate the effectiveness of the quadrivalent HPV vaccine in comparison to the candida antigen and the placebo.

However, the current study had some limitations as it is a single center study and recruited a relatively small sample size that could decrease the power of the obtained results, and there was no efficacy analysis taking into account the size and duration of the lesions. Also, the short duration of follow up did not enable to comment on the long-term outcomes especially the rate of recurrence.

Based on our findings, intralesional antigen immunotherapy seems to be an effective therapeutic option for the treatment of non-genital warts. Additionally, we came to the conclusion that the efficacy of intralesional quadrivalent HPV vaccine was superior to intralesional candida antigen.

Footnotes

Funding: None.

Competing Interests: None.

Authorship: All authors have contributed significantly to this publication.

References

- 1.Doorbar J, Egawa N, Griffin H, Kranjec C, Murakami I. Human papillomavirus molecular biology and disease association. Rev Med Virol. 2015;25(Suppl 1(Suppl Suppl 1)):2–23. doi: 10.1002/rmv.1822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bacaj P, Burch D. Human Papillomavirus Infection of the Skin. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2018;142(6):700–705. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2017-0572-RA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Loo SK, Tang WY. Warts (non-genital) BMJ Clin Evid. 2014;2014:1710. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dall’oglio F, D’Amico V, Nasca MR, Micali G. Treatment of cutaneous warts: an evidence-based review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2012;13(2):73–96. doi: 10.2165/11594610-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gheisari M, Iranmanesh B, Nobari NN, Amani M. Comparison of long-pulsed Nd: YAG laser with cryotherapy in treatment of acral warts. Lasers Med Sci. 2019;34(2):397–403. doi: 10.1007/s10103-018-2613-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nofal A, Marei A, Amer A, Amen H. Significance of interferon gamma in the prediction of successful therapy of common warts by intralesional injection of Candida antigen. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56(10):1003–1009. doi: 10.1111/ijd.13709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aldahan AS, Mlacker S, Shah VV, et al. Efficacy of intralesional immunotherapy for the treatment of warts: A review of the literature. Dermatol Ther. 2016;29(3):197–207. doi: 10.1111/dth.12352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garg S, Baveja S. Intralesional immunotherapy for difficult to treat warts with Mycobacterium w vaccine. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2014;7(4):203–208. doi: 10.4103/0974-2077.150740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chaudhary M, Brar A, Agarwal P, Chavda V, Jagati A, Rathod SP. A Study of Comparison and Evaluation of Various Intralesional Therapies in Cutaneous Warts. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2023;14(4):487–492. doi: 10.4103/idoj.idoj_492_22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ju HJ, Park HR, Kim JY, Kim GM, Bae JM, Lee JH. Intralesional immunotherapy for non-genital warts: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2022;88(6):724–737. doi: 10.25259/IJDVL_1369_20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brunk D. Injection of Candida antigen works on warts. Skin Allergy News. 1999;30:5. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Villa LL, Costa RL, Petta CA, et al. Prophylactic quadrivalent human papillomavirus (types 6, 11, 16, and 18) L1 virus-like particle vaccine in young women: a randomised double-blind placebo-controlled multicentre phase II efficacy trial. Lancet Oncol. 2005;6(5):271–278. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(05)70101-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Venugopal SS, Murrell DF. Recalcitrant cutaneous warts treated with recombinant quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine (types 6, 11, 16, and 18) in a developmentally delayed, 31-year-old white man. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146(5):475–477. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2010.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abeck D, Fölster-Holst R. Quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccination: a promising treatment for recalcitrant cutaneous warts in children. Acta Derm Venereol. 2015;95(8):1017–2029. doi: 10.2340/00015555-2111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marei A, Boghdadi G, Tash RME, Elgharabawy E. Efficacy of intralesional Candida antigen immunotherapy in treatment of recalcitrant warts. Z. agazig University Medical Journal. 2020;26(5):769–774. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nassar A, Alakad R, Essam R, Bakr NM, Nofal A. Comparative efficacy of intralesional Candida antigen, intralesional bivalent human papilloma virus vaccine, and cryotherapy in the treatment of common warts. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87(2):419–421. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2021.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Signore RJ. Candida albicans intralesional injection immunotherapy of warts. Cutis. 2002;70(3):185–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clifton MM, Johnson SM, Roberson PK, Kincannon J, Horn TD. Immunotherapy for recalcitrant warts in children using intralesional mumps or Candida antigens. Pediatr Dermatol. 2003;20(3):268–271. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1470.2003.20318.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Horn TD, Johnson SM, Helm RM, Roberson PK. Intralesional immunotherapy of warts with mumps, Candida, and Trichophyton skin test antigens: a single-blinded, randomized, and controlled trial. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141(5):589–594. doi: 10.1001/archderm.141.5.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.King M, Johnson SM, Horn TD. Intralesional immunotherapy for genital warts. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141(12):1606–1607. doi: 10.1001/archderm.141.12.1606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Majid I, Imran S. Immunotherapy with intralesional Candida albicans antigen in resistant or recurrent warts: a study. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58(5):360–365. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.117301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alikhan A, Griffin JR, Newman CC. Use of Candida antigen injections for the treatment of verruca vulgaris: A two-year mayo clinic experience. J Dermatolog Treat. 2016;27(4):355–358. doi: 10.3109/09546634.2015.1106436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nofal A, Salah E, Nofal E, Yosef A. Intralesional antigen immunotherapy for the treatment of warts: current concepts and future prospects. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013;14(4):253–260. doi: 10.1007/s40257-013-0018-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnson SM, Roberson PK, Horn TD. Intralesional injection of mumps or Candida skin test antigens: a novel immunotherapy for warts. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137(4):451–455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nofal A, Khattab F, Nofal E, Elgohary A. Combined acitretin and Candida antigen versus either agent alone in the treatment of recalcitrant warts. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79(2):377–378. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cyrus N, Blechman AB, Leboeuf M, et al. Effect of Quadrivalent Human Papillomavirus Vaccination on Oral Squamous Cell Papillomas. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151(12):1359–1363. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.2805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gattoc L, Nair N, Ault K. Human papillomavirus vaccination: current indications and future directions. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2013;40(2):177–197. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2013.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Salman S, Shehata SAM, Ibrahim AM, et al. Efficacy of retinoids alone or in combination with other remedies in the management of warts: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34(2):e14793. doi: 10.1111/dth.14793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ferguson SB, Gallo ES. Nonavalent human papillomavirus vaccination as a treatment for warts in an immunosuppressed adult. JAAD Case Rep. 2017;3(4):367–369. doi: 10.1016/j.jdcr.2017.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fathy G, Abo-Elmagd WM, Afify AA. Intralesional combined digoxin and furosemide in plantar warts: Does it work? J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20(8):2606–2611. doi: 10.1111/jocd.13913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mohammed GF, Afify AA-E, Abdel Latif WMAE. Ionic Anti-Viral Intralesional Therapy in Plantar Warts. QJM: An International Journal of Medicine. 2021;114(Supplement_1):hcab093. [Google Scholar]