Abstract

Anatomy is a foundational subject in medicine and serves as its language. Hippocrates highlighted its importance, while Herophilus pioneered human dissection, earning him the title of the founder of anatomy. Vesalius later established modern anatomy, which has since evolved historically. In Korea, formal anatomy education for medical training began with the introduction of Western medicine during the late Joseon Dynasty. Before and after the Japanese occupation, anatomy education was conducted in the German style, and after liberation, it was maintained and developed by a small number of domestic anatomists. Medicine in Korea has grown alongside the country’s rapid economic and social development. Today, 40 medical colleges produce world-class doctors to provide the best medical care service in the country. However, the societal demand for more doctors is growing in order to proactively address to challenges such as public healthcare issues, essential healthcare provision, regional medical service disparities, and an aging population. This study examines the history, current state, and challenges of anatomy education in Korea, emphasizing the availability of medical educators, support staff, and cadavers for gross anatomy instruction. While variations exist between Seoul and provincial medical colleges, each manages to deliver adequate education under challenging conditions. However, the rapid increase in medical student enrollment threatens to strain existing anatomy education resources, potentially compromising educational quality. To address these concerns, we propose strategies for training qualified gross anatomy educators, ensuring a sustainable cadaver supply, and enhancing infrastructure.

Keywords: Anatomy Education, Medical Students, Anatomy Educator, Cadaver, Anatomy History, Korea

INTRODUCTION

The history of anatomy in ancient times was the history of medicine. Anatomy has been described as the cornerstone of good medical practice1 and the foundation for clinical studies.2 The first person known to have dissected the human body in the western world to understand its structure and function was Alcmaeon of Croton, who lived in ancient Greece around 500 BC.3,4 Hippocrates (BC 460–377) had the belief that medicine should be practiced as a scientific discipline based on the natural sciences, diagnosing and preventing diseases as well as treating them. Also, he believed that physicians should study anatomy.5 During a brief period in ancient history when human dissection was permitted, Herophilus (BC 330–280) and Erasistratos (BC 310–250) revealed the structure and function of the human body through dissection.6 Galen (AD 131–200) advanced anatomical knowledge inherited from his predecessors by supplementing it with insights gained through patient care and animal dissection. He also offered scientific insights into pathophysiology, linking it with disease.7 For approximately 1,300 years, Galen remained a prominent figure in western medicine. Human dissection was prohibited during the Middle Ages. However, in the 13th century, Mondino (1276–1326) published “Anathomia” in 1316, which solidified the importance of anatomy in medical education.8,9

Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) is considered the most outstanding figure among Renaissance artists who studied anatomy. He attempted to understand the human form and function by correlating them, leaving behind over 750 anatomical drawings that are both artistically beautiful and scientifically accurate.3,10 Later, Vesalius (1514–1564), often regarded as the father of modern anatomy, significantly contributed to the field with the publication of the detailed “De Humani Corporis Fabrica” in 1543, establishing anatomy as the cornerstone of modern medicine.10,11

In the early 19th century (1828), there was an explosive population growth in Britain, leading to a significant increase in students aspiring to become doctors. This surge resulted in the establishment and popularization of anatomy and medical schools.12 Many of these students, after their studies, played a crucial role in founding the Department of Anatomy in universities and spreading the teaching of anatomy worldwide.13 At that time, there was a high demand for cadavers for students' dissection practices in medical schools, but the supply was critically low. Cadavers were clandestinely traded in illegal markets.14,15 However, body snatchers or grave robbers significantly contributed to anatomical teaching and played a vital role in advancing anatomy.12,14,16 Due to murders associated with the illicit trade of cadavers, the Anatomy Act was enacted by the British Parliament on August 1, 1832, catalyzing to recognition of the need for anatomical dissection in medical training.12,17 Before 1825, the medical curriculum in Britain consisted of basic sciences and clinical subjects. According to Rothstein, anatomy was fundamental and the most popular and important subject in medical schools.18

Modern anatomy education includes gross anatomy, histology, neuroanatomy, and embryology. The advent of advanced imaging methods like CT and MRI has coincided with the advancement of minimally invasive treatments aimed at particular organs or locations within them. Consequently, a solid grasp of gross anatomy has become more crucial, not just for interpreting the images generated by these advanced techniques, but also for comprehending the route for directing therapy to a precise location.19 In addition, gross anatomy education helps students develop medical professionalism at the initial stage of entering medicine.20,21 It is also recognized to have a significant impact on students' career paths, with those who have experience performing cadaver dissection being more inclined to specialize in surgery,22 which is an essential field of medical practice.

In Korea, though it is known that the concept of anatomy was introduced in the Age of Three Kingdoms, anatomy in the modern sense meaning was introduced in the late Joseon Dynasty by western missionary doctors. Since then, anatomy education has played an important role in helping the poorest countries grow to the point where they can provide world-class medical services after colonial rule and the Korean War. Recently, the Korean government announced a plan to increase the medical college seats as a response to the medical demand triggered by public healthcare, essential healthcare, regional imbalances in medical services, and an aging society.23 This brief review focuses on the past and present status of gross anatomy education in Korea, which is the basis of medical education, which holds the greatest contact hours and huge infrastructure for laboratories. In preparation for this review, we conducted a brief telephone survey to determine the current state of anatomy education in Korea and present the results here. In addition, we will simulate the demand for gross anatomy education expected when the government's planned increase in the number of medical college seats progresses. Finally, we will discuss the possibility of solving the problem triggered by the abrupt increase in medical students.

HISTORY OF ANATOMY EDUCATION IN KOREA

While the history of anatomy in Korea is quite long, the actual teaching of anatomy to train doctors began with the introduction of western medicine during the late Joseon Dynasty.24,25 Although anatomy education began with the establishment of medical schools, hands-on dissection started in 1910. From the 1920s onwards, not only dissection practices but also active research on the bones and organs of Koreans through actual dissections became more prevalent.24 Before Korea’s liberation on August 15, 1945, anatomy education in Korea adopted the German-style teaching methods used by Japanese anatomists. After liberation, anatomy education continued to be conducted by anatomists trained during the Japanese colonial period.24,25,26 At that time, anatomy education utilized textbooks from the Japanese colonial era, and there was a severe shortage of professors specialized in anatomy.26 The teaching methods for anatomy were carried out through verbal lectures and educational charts, and the lectures were mainly focused on note-writing.26

In the 1950s, overcoming the painful scars of the Korean War, anatomy education in some medical colleges was conducted as printed-based lectures, and gradually changed to film slide-based lectures.24,25,26 In the early 1970s, with the revision of the medical college curriculum, the hours dedicated to anatomy education were significantly reduced.26 In the 1980s, with the establishment of many new medical colleges, the total number increased to 28. Each newly established medical college had its own unique curriculum.26 During this period, the number of anatomy professors in each medical college was one (4.4%, one college), two (21.7%, five colleges), and three (34.8%, eight colleges), with most of the three or fewer (60.9%) professors in charge of anatomy education.26,27 In the 1990s, the number of medical colleges in Korea sharply increased to a total of 37. In most medical colleges (78.3%), the number of professors responsible for anatomy ranged from 2 to 4.26 With the reduction in anatomy education hours, the teaching method shifted from systematic anatomy to regional anatomy. Some medical schools introduced integrated education (integration of basic medical subjects or integration of basic medical and clinical subjects), leading to changes in traditional anatomy teaching methods.25,26 In the 1990s, the total anatomy education hours (including lectures and practice) varied significantly by medical colleges, but the average was 234.5 hours.26 Since the introduction of the medical graduate school system in the 2000s, most medical colleges have increased clinical practice hours. As a result, not only anatomy but also other basic medical subjects have seen a significant reduction in educational hours.24,25

From the 1970s, as society stabilized, the supply of cadavers for anatomy education decreased. With the increase in newly established medical colleges, anatomy dissection faced many challenges. Especially after the ‘Busan Hyungje Welfare Center Incident’ and the ‘Daejeon Seongji Center Incident’ in 1987, coupled with the non-cooperation of officials from related agencies and changes in social welfare systems, the procurement of cadavers became extremely difficult.24,25 At that time, there were medical colleges where 30 to 40 students dissected one cadaver, reflecting the serious state of anatomy education.24,25 However, with the activation of the organ donation campaign that began in the 1980s, the number of cadaver donors for anatomy education increased. As a result, the situation regarding cadaver procurement began to improve gradually in the late 1990s.24 Since the 2000s, cadavers donated for anatomy dissection in Korea have been legally provided to medical colleges. Most medical colleges rigorously manage and respect the cadavers, ensuring that remains are treated with dignity, either through respectful cremation or burial.24,25 As a result, the widely promoted cadaver donation programs are operating successfully, and public awareness of cadaver donation and dissection has been improving. Currently, most of the cadavers used for anatomy dissection are donated.

CURRENT STATUS AND ISSUES OF ANATOMY EDUCATION IN KOREA

A survey was conducted targeting 40 medical colleges nationwide (3 groups according to their locations, Table 1) to investigate the number of students attending anatomy lectures and practical sessions, the number of anatomy professors, the number of professors responsible for gross anatomy lectures and practical sessions, the number of staff members responsible for cadaver management, the number of teaching assistants responsible for gross anatomy education, and the number of cadavers used in gross anatomy practical sessions. The survey was conducted via telephone calls with the anatomy education coordinator of each college in April 2024, and the data were collected based on the average numbers over the past five years.

Table 1. Groups of medical colleges in Korea.

| Group | Region | University |

|---|---|---|

| A | Seoul | The Catholic University of Korea |

| Chung-Ang University | ||

| Ewha Womans University | ||

| Hanyang University | ||

| Korea University | ||

| Kyung Hee University | ||

| Seoul National University | ||

| Yonsei University | ||

| B | Gyeongi-do, Incheon | Ajou University |

| CHA University | ||

| Gachon University | ||

| Inha University | ||

| Sungkyunkwan University | ||

| C | All provinces except Seoul metropolitan area | Catholic Kwandong University |

| Catholic University of Daegu | ||

| Chonnam National University | ||

| Chosun University | ||

| Chungbuk National University | ||

| Chungnam National University | ||

| Dankook University | ||

| Dong-A University | ||

| Dongguk University | ||

| Eulji University | ||

| Gyeongsang National University | ||

| Hallym University | ||

| Inje University | ||

| Jeju National University | ||

| Jeonbuk National University | ||

| Kangwon National University | ||

| Keimyung University | ||

| Konkuk University | ||

| Konyang University | ||

| Kosin University | ||

| Kyungpook National University | ||

| Pusan National University | ||

| Soon Chun Hyang University | ||

| University of Ulsan | ||

| Wonkwang University | ||

| Yeungnam University | ||

| Yonsei University Wonju |

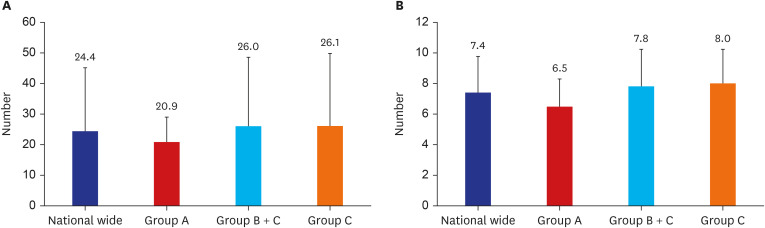

The number of students enrolled in anatomy courses exceeded the official capacity due to additional enrollees, re-takers of classes, etc. (Official capacity: 3,058 students, actual number of students taking anatomy courses: approximately 3,246 students). The average number of anatomy professors per medical college was 4.5, with Group A having an average of 6.5 professors, which was higher than the average of 3.9 professors in Groups B and C (Fig. 1, P = 0.000, Student’s t-test, two-tailed). The average number of professors responsible for gross anatomy lectures and practical sessions was 3.3 per college, indicating that approximately 86.7% of all anatomy professors are involved in teaching gross anatomy lectures and practical sessions (Fig. 1). Thus, most anatomy professors seem to be actively engaged in both gross anatomy lectures and practical sessions. On the other hand, among the eight medical colleges in Group A, the average number of professors responsible for gross anatomy lectures and practical sessions was 5.3 per college, higher than the average of 3.3 professors in the other Groups (Fig. 1, P = 0.001, Student’s t-test, two-tailed). Regarding the number of teaching assistants (TAs) responsible for gross anatomy education, it was found that nationally, each college had fewer than one TA. However, the eight medical colleges in Group A had an average of 2.0 TAs per college, which was more than four times the average of 0.5 TAs in the other Groups (Fig. 1, P = 0.000, Student’s t-test, two-tailed).

Fig. 1. Current status of human resources for gross anatomy education in Korea.

Height = average, Error bar = standard deviation.

*P < 0.05.

In terms of the cadavers essential for gross anatomy practical sessions, approximately 450 cadavers are utilized annually for medical students’ anatomy education. While there are variations depending on the Group, the ratio of students to cadavers stands at 7.4 (Fig. 1, 3,246 students/438 cadavers) in Korea. This indicates a challenging educational environment compared to the United States, where the ratio is 5.1 students per cadaver.28 Nationally, each medical college utilizes an average of 11.0 cadavers for anatomy practical sessions. In the eight medical colleges in Group A, the average stands at 16.9 cadavers per college, which is 77.9% higher than the average of 9.5 cadavers in the other Groups (Fig. 1, P = 0.000, Student’s t-test, two-tailed). Regarding the staff responsible for managing the cadavers, the survey found an average of 1.3 staff members per medical college. In the eight universities in Group A, the average was 2.4 staff members per college, while in the medical colleges of Groups B and C, the average was 1.1 staff members per college. This indicates that medical colleges of Group A have more than twice the number of staff compared to the other Groups (Fig. 1, P = 0.000, Student’s t-test, two-tailed). There were no statistically significant differences observed in any of the metrics between Group B and Group C.

Given that the eight medical colleges in Group A have more professors, teaching assistants, cadaver management staff, and cadavers compared to the others in Group B and C it is evident that there is a significant disparity in educational conditions for gross anatomy lectures and practical sessions across the Groups. Since the content and volume of anatomy lectures and practical sessions are expected to be relatively consistent across colleges, it suggests that professors and education assistants in medical colleges in Groups B and C are handling more anatomy-related educational tasks compared to those in the eight medical colleges in Group A. On the other hand, while there was a slight difference in the student-to-professor ratio for anatomy education across Groups, with an average of 24.4 students per professor nationwide, 20.9 in Group A, and 26.0 in Group B and C, this difference was not statistically significant (Fig. 2A). Similarly, the student-to-cadaver ratio was slightly different across Groups, with an average of 7.4 students per cadaver nationwide, 6.5 in Group A, and 7.8 in Groups B and C, but again, this difference was not statistically significant (Fig. 2B). The reason the student-to-professor and student-to-cadaver ratios in Groups B and C are similar to those in Group A, despite having fewer professors and cadavers, could be attributed to the significantly higher student number in the eight medical colleges in Group A. The average student number in Group A’s eight medical colleges is 109.5 students, which is statistically significantly higher than the average of 74.1 students in the other Groups (Fig. 3, P = 0.020, Student’s t-test, two-tailed).

Fig. 2. Current student-to-professor ratio for anatomy education and student-to-cadaver ratio in Korea. (A) Student-to-anatomy professor ratio in Korea. (B) Student-to-cadaver ratio in Korea.

Height = average, Error bar = standard deviation.

Fig. 3. Number of students of medical colleges in Korea.

Height = average, Error bar = standard deviation.

*P < 0.05.

The recruitment of professors capable of conducting gross anatomy lectures and practical sessions has become increasingly challenging in recent years. Primarily, there is a limited number of graduate students specializing in gross anatomy due to its nature as a niche field. Moreover, not many professionals meet the expectations of universities in terms of both teaching and research capabilities. As a result, many universities have been unable to fill vacant anatomy professor positions despite posting job openings for several years. Consequently, some universities have resorted to appointing professionals from other disciplines with strong research capabilities as anatomy professors. These individuals either handle other subfields of anatomy, such as neuroanatomy, histology, and embryology or deliver gross anatomy lectures without participating in practical sessions, merely transmitting textbook content without verifying their teaching skills (personal communication). This ongoing cycle makes it increasingly difficult to attract students who aspire to specialize in gross anatomy or become future anatomy professors, perpetuating a vicious cycle of limited recruitment and specialized training in the field.

In summary, as of 2023, the 32 medical colleges of Groups B and C fall significantly short in terms of anatomy lectures and practical session professors, teaching assistants, cadavers, and cadaver management staff compared to the eight medical colleges in Group A. However, due to a smaller student population, these colleges maintain a gross anatomy educational environment that is somewhat comparable to that of medical colleges in Group A. Nevertheless, the workload per professor and per teaching assistant is likely higher in the 32 medical colleges of Groups B and C than in those of Group A. The current study focused primarily on gross anatomy among various subjects taught in anatomy classrooms due to time constraints. This study focused on examining the human resources, cadaver status, and infrastructure related to education. Subsequent research will be necessary to investigate other subjects and explore aspects such as the number of educational hours, practical session hours, and teaching methods for these subjects.

ANTICIPATED CHALLENGES IN ANATOMY EDUCATION WITH THE INCREASE IN MEDICAL COLLEGE SEATS

If the number of medical college students continues to increase, it is anticipated that the anatomy education environments, which have been barely maintained despite limited educational resources, will significantly deteriorate. Particularly, an increase in the student population at medical colleges of Groups B and C is expected to further worsen the anatomy education environment. Table 2 predicts the situation at anatomy education sites based on the scale of the increase in medical college admissions. The current nationwide student-to-anatomy professor ratio is 24.4 students per professor, and the ratio of students per cadaver is 7.4 (Fig. 2). To maintain these ratios with an increase in student numbers by 500, 1,000, and 2,000, we calculated the additional professors and cadavers needed (Table 2). For an increase of 500 students, approximately 20 more anatomy professors and 68 additional cadavers would be required. For an increase of 1,000 students, about 41 more professors and 135 additional cadavers would be needed. For an increase of 2,000 students, roughly 82 more professors and 270 additional cadavers would be necessary.

Table 2. Numbers of professors and cadavers needed to maintain the current anatomy education environments for each possible increase in the number of medical college seats in Korea.

| Increased number of medical college seat | 0 | 500 | 1,000 | 2,000 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of professors needed | 0 | 20 | 41 | 82 |

| Number of cadavers needed | 0 | 68 | 135 | 270 |

Considering the current number of anatomy professors nationwide is 92 (25 in Group A and 67 in Groups B and C), and there are 30 TAs responsible for anatomy education nationwide, it appears to be extremely challenging to secure the additional anatomy professors and TAs needed in the short term. In the case of an increase of 2,000 students, even if all the 30 anatomy TAs nationwide are promoted to professors, there will still be a shortage of 52 professors, leaving no assistants remaining. A more significant challenge is that many of the current professors responsible for anatomy education, around 23, are expected to retire within the next five years.29 In the cases of University A in Gyeonggi-do and University B in Gyeongsang-do, two anatomy teaching professors from each institution are set to retire within the next two years. To prepare additional cadavers, the number of staff members responsible for cadavers must also increase.

At present, each anatomy professor in Korea handles 24.4 students, and even when including TAs who participate in practical training as capable individuals, the number is 17.8 students per faculty member. In contrast, the United Kingdom (UK) has a ratio of 13.3 students per educator,30 indicating a severe shortage of qualified educators for gross anatomy education in Korea. Given this situation, an increase in medical college enrolment would undoubtedly exacerbate the inadequacies in gross anatomy education. Considering the number of current gross anatomy professors who are expected to retire within the next five years, it’s not difficult to anticipate a further shortage of instructors capable of teaching gross anatomy, even if there is no increase in medical student enrolment. This pressing issue needs to be addressed promptly to prevent a decline in the quality of anatomy education.

Finally, to support anatomy education, infrastructural elements such as lecture halls, labs, and multimedia environments are essential. While this review did not delve into the specific numbers for each university's educational infrastructure, most institutions only have infrastructure tailored to their current student numbers. Therefore, an increase in medical college seats requires not only securing human and cadaver resources for anatomy education but also investing in educational infrastructure. Just as University C in the Jeolla-do which saw an increase in enrolment following the closure of Seonam University, took approximately five years to establish educational infrastructure aligned with the increased numbers showing that the planning, design, and construction processes require not only financial resources but also considerable time. Thus, significant challenges are anticipated until educational environments adapted to the increased student body are fully prepared.

PROPOSAL TO MAINTAIN THE QUALITY OF ANATOMY EDUCATION IN KOREA

Given the current state and conditions of gross anatomy education in Korea, along with the societal demand for an increase in healthcare professionals, we aim to address the anticipated challenges in gross anatomy education due to this expansion. Specifically, we propose the following recommendations concerning the training of personnel capable of teaching gross anatomy and the supply of cadavers, which serve as the material basis for education.

Faculty recruitment strategy

Establishment of an anatomy educator national fellow (basic medical educator fellow) program

The most significant challenge in the current gross anatomy faculty recruitment lies in the shortage of qualified faculty. Basic medical subjects, including gross anatomy, are essential components of clinical practice. To cultivate faculty capable of teaching gross anatomy, a system akin to providing subsidies to pediatricians and thoracic surgeons, who specialize in essential medical fields, should be instituted for graduate students majoring in basic medical sciences like anatomy. This program should be designed not only to attract doctors who have graduated from medical colleges but also to bring in other highly qualified talents from various disciplines. Currently, the government’s ongoing physician-scientist training program focuses on enhancing the research capabilities of clinical doctors. Expanding this concept to include the training of educational experts in essential basic medical fields could foster a pool of faculty in basic medical sciences.

Anatomy educator matching program

The current landscape of gross anatomy education is characterized by a significant shortage of faculty. To address this issue in the short term, leveraging doctoral students, postdoctoral researchers, and retired anatomists can be a viable option. However, connecting the demand in the field with the potential educational workforce has proven challenging. To address this gap, the establishment of an “Anatomy Educator Matching Program” within the Korean Association of Anatomists (KAA) can be proposed. This program would aim to build a pool of potential educators and facilitate connections between educational institutions and available anatomy educators. By matching institutions with verified anatomy educators, this program can provide temporary relief to the shortage of anatomy faculty and also enable training for the next generation of anatomy educators.

Qualified anatomy educator certificate

To maintain the quality of gross anatomy education, it is essential to certify professors and instructors who can effectively teach and guide practical sessions in gross anatomy. Monitoring should also be in place to ensure that proper education and practical training are consistently provided. This should be integrated into medical college accreditation evaluations to encourage universities to prioritize effective gross anatomy education. Similar to the “Supervising Specialist” system implemented by the Korean Hospital Association (KHA) in clinical medicine, a system could be developed for gross anatomy education. This system would certify educators with over four years of experience, including practical training, in gross anatomy and who possess research capabilities. The Korean Association of Anatomists could certify these individuals as specialized gross anatomy instructors and maintain continuous educational oversight. By utilizing these certified educators to deliver gross anatomy lectures and practical sessions to medical students, the quality of gross anatomy education can be maintained and even improved.

Maintaining diverse hiring tracks for anatomy education specialists

According to 2019 statistics from the UK, among 760 anatomy educators across 39 medical schools, 103 are professors who combine both anatomy research and teaching. In contrast, 143 are professors dedicated solely to anatomy education, supported by 514 anatomy demonstrators.30 Among these, the 143 professors focused solely on anatomy education deserve attention. As mentioned earlier, due to the nature of gross anatomy, it can be challenging to find professors who excel equally in both research and teaching. Instead of hiring professors based solely on their research capabilities, there seems to be a trend in employing dedicated anatomy education specialists. This suggests that medical colleges in Korea should consider utilizing diverse hiring tracks, similar to those observed in the UK. (Note: Anatomy demonstrators are doctors who have completed a two-year internship and are in the stage of refining surgical skills and enhancing competencies through assisting in anatomy classrooms before entering the surgical field.)

Securing cadavers for anatomy education

Recently, efforts have been made to replace anatomy labs with technologies such as augmented reality (AR) and virtual reality (VR) for anatomy education. AR and VR have been proven effective in understanding human organs and structures in three dimensions, aiding in the perception of their spatial relationships. Consequently, their use as supplementary educational materials and tools in gross anatomy education, particularly in practical training, has increased.31,32 Despite these advancements, certain essential contents that medical professionals must acquire, such as anatomical techniques, understanding of human dignity, and medical professionalism, cannot be learned solely through simulations.28,33,34 Thus, the importance of cadaveric training in graduate medical education (GME) in surgical disciplines has grown.33,35,36 In fact, a lack of cadaveric education has resulted in a significant decline in the number of doctors choosing surgical fields as their careers.19 Consequently, many medical education institutions continue to prioritize anatomy practical sessions, and the situation is no different in South Korea. Therefore, securing an adequate number of cadavers is crucial for anatomy training.

Currently, South Korea receives approximately 1,100–1,200 body donations annually, which are used for medical student anatomy education, GME for clinical physicians, and gross anatomy research in life sciences.37 With the increasing emphasis on cadaver-based practical training in GME, coupled with legal revisions regarding body dissection and preservation for life science research, the shortage of cadavers will inevitably worsen with an increase in medical student enrolments. To address this, efforts should focus on improving awareness and promoting cadaver donation, extending respect and support to cadaver donors and their families,38 and supporting universities and practitioners responsible for cadaver collection, utilization, and disposal. Considering the difficulties in cadaver supply faced by some medical schools in the United States, establishing and operating regional cadaver centers could also be considered.37 Moving forward, collaboration among medical colleges, university hospitals, societies, local governments, and government departments will be essential to devise solutions for securing educational cadavers.

Infrastructure support

Securing adequate infrastructure is essential for providing quality anatomy education. This encompasses space allocation, facility construction, and acquiring the necessary equipment. Ultimately, addressing these challenges requires substantial financial resources and both short-term and long-term development plans. To resolve these issues, research projects and national financial support are essential for providing the necessary backing and resources.

CONCLUSION

In the relatively brief period since the introduction of western medicine to Korea, anatomy education in Korea has played a significant role in shaping proficient medical professionals. This review of the current state of anatomy education reveals variations in educational conditions across medical colleges. Although each institution strives to maintain a high standard of education despite challenging circumstances, the field faces fragility and numerous challenges, particularly in aspects like the availability of anatomy educators, cadaver supply, and infrastructure. It is evident that an abrupt increase in the number of medical students amid these challenges could jeopardize the quality of anatomy education. To address this, there is a pressing need to establish a comprehensive mid- to long-term development strategy. Such a plan requires sufficient time and financial investment to tackle issues including the recruitment of qualified medical educators, ensuring an adequate supply of cadavers, and improving infrastructure. Only through these concerted efforts can the integrity and quality of anatomy education be upheld in the face of evolving demands (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Expected problems and possible solution for future anatomy education in Korea.

Footnotes

- Conceptualization: Kim IB, Joo KM, Song CH, Rhyu IJ.

- Methodology: Kim IB, Joo KM.

- Analysis: Kim IB, Joo KM.

- Writing - original draft: Kim IB, Joo KM, Song CH, Rhyu IJ.

- Writing - review & editing: Kim IB, Joo KM, Song CH, Rhyu IJ.

References

- 1.Davis CR, Bates AS, Ellis H, Roberts AM. Human anatomy: let the students tell us how to teach. Anat Sci Educ. 2014;7(4):262–272. doi: 10.1002/ase.1424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sugand K, Abrahams P, Khurana A. The anatomy of anatomy: a review for its modernization. Anat Sci Educ. 2010;3(2):83–93. doi: 10.1002/ase.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Persaud TV. Early History of Human Anatomy. Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas; 1984. pp. 29–30. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Debernardi A, Sala E, D’Aliberti G, Talamonti G, Franchini AF, Collice M. Alcmaeon of Croton. Neurosurgery. 2010;66(2):247–252. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000363193.24806.02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kleisiaris CF, Sfakianakis C, Papathanasiou IV. Health care practices in ancient Greece: the Hippocratic ideal. J Med Ethics Hist Med. 2014;7(6):6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reverón RR. Herophilus and Erasistratus, pioneers of human anatomical dissection. Vesalius. 2014;20(1):55–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dunn PM. Galen (AD 129-200) of Pergamun: anatomist and experimental physiologist. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2003;88(5):F441–F443. doi: 10.1136/fn.88.5.F441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilson L. The performance of the body in the renaissance theater of anatomy. Representations (Berkeley) 1987;17:62–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crivellato E, Ribatti D. Mondino de’ Liuzzi and his Anothomia: a milestone in the development of modern anatomy. Clin Anat. 2006;19(7):581–587. doi: 10.1002/ca.20308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Persaud TV, Loukas M, Tubbs RS. A History of Human Anatomy. Springfield, IL, USA: Charles C Thomas; 2014. pp. 60–68.pp. 72–75. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singer CJ. A Short History of Anatomy From the Greeks to Harvey. New York, NY, USA: Dover Publications; 1957. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Desmond A. The Politics of Evolution. Morphology, Medicine, and Reform in Radical London. Chicago, IL, USA: University of Chicago Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cope Z. In: The Evolution of Medical Education in Britain. Poynter FNL, editor. London, UK: Pitman Medical; 1966. The private medical schools in London (1746-1914) [Google Scholar]

- 14.Richardson R. Death, Dissection and the Destitute. London, UK: Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coakley D. In: The Anatomy Lesson: Art and Medicine. Kennedy BP, Coakley D, editors. Dublin, Ireland: The National Gallery of Ireland; 1992. Anatomy and art: Irish dimensions; pp. 57–58. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shultz SM. Body Snatching. Jefferson, NC, USA: McFarland; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Richardson R. In: British Medicine in an Age of Reform. French R, Wear A, editors. London, UK: Routledge; 1991. “Trading assassins” and the licensing of anatomy; pp. 74–91. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rothstein WG. American Medical Schools and the Practice of Medicine. New York, NY, USA: Oxford University Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 19.McCuskey RS, Carmichael SW, Kirch DG. The importance of anatomy in health professions education and the shortage of qualified educators. Acad Med. 2005;80(4):349–351. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200504000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chang HJ, Kim HJ, Rhyu IJ, Lee YM, Uhm CS. Emotional experiences of medical students during cadaver dissection and the role of memorial ceremonies: a qualitative study. BMC Med Educ. 2018;18(1):255. doi: 10.1186/s12909-018-1358-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Choi GY, Kim JM, Seo JH, Sohn HJ. Becoming a doctor through learning anatomy: narrative analysis of the educational experience. Korean J Phys Anthropol. 2009;22(3):213–224. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Franchi T. The impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on current anatomy education and future careers: a student’s perspective. Anat Sci Educ. 2020;13(3):312–315. doi: 10.1002/ase.1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Park B. Gov’t set to announce allocation of increased medical school seats. Yonhap News; [Updated 2024]. [Accessed April 8, 2024]. https://en.yna.co.kr/view/AEN20240320001600315 . [Google Scholar]

- 24.Korean Association of Anatomists. History of Korean Anatomy. Seoul, Korea: Book publishing Jeong Seok; 2017. pp. 35pp. 42pp. 46pp. 164–175.pp. 186pp. 188 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Korean Association of Basic Medical Scientists. History of Korean Basic Medical Science. Seoul, Korea: Korean Association of Basic Medical Scientists; 2008. pp. 63–67. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Korean Association of Anatomists. 50th Anniversary of Korean Association of Anatomists. Seoul, Korea: Hamchun Hanhwa; 1997. pp. 35–37.pp. 40 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Korean Association of Anatomists. Yesterday and Today of Korean Anatomy Education. Seoul, Korea: Gyechuk Munhwasa; 1987. p. 50. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shin M, Prasad A, Sabo G, Macnow AS, Sheth NP, Cross MB, et al. Anatomy education in US medical schools: before, during, and beyond COVID-19. BMC Med Educ. 2022;22(1):103. doi: 10.1186/s12909-022-03177-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim W, Kim MK, Yoo SM, Jung SH, Kim MJ, Kim SJ, et al. The Current Status and Future of Basic Medical Education in Korea. Seoul, Korea: Korea Association of Medical Colleges; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smith CF, Freeman SK, Heylings D, Finn GM, Davies DC. Anatomy education for medical students in the United Kingdom and Republic of Ireland in 2019: A 20-year follow-up. Anat Sci Educ. 2022;15(6):993–1006. doi: 10.1002/ase.2126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ye Z, Dun A, Jiang H, Nie C, Zhao S, Wang T, et al. The role of 3D printed models in the teaching of human anatomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1):335. doi: 10.1186/s12909-020-02242-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.da Cruz Torquato M, Menezes JM, Belchior G, Mazzotti FP, Bittar JS, Dos Santos GG, et al. Virtual reality as a complementary learning tool in anatomy education for medical students. Med Sci Educ. 2023;33(2):507–516. doi: 10.1007/s40670-023-01774-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Memon I. Cadaver dissection is obsolete in medical training! A misinterpreted notion. Med Princ Pract. 2018;27(3):201–210. doi: 10.1159/000488320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tugtag Demir B, Altintas HM, Bilecenoglu B. Investigation of medical faculty students’ views on cadaver and cadaver teaching in anatomy. Morphologie. 2023;107(356):47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.morpho.2022.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tjalma WA, Degueldre M, Van Herendael B, D’Herde K, Weyers S. Postgraduate cadaver surgery: an educational course which aims at improving surgical skills. Facts Views Vis Obgyn. 2013;5(1):61–65. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Attaluri P, Wirth P, Gander B, Siebert J, Upton J. Importance of cadaveric dissections and surgical simulation in plastic surgery residency. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2022;10(10):e4596. doi: 10.1097/GOX.0000000000004596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim IB, Hwang SJ, Lee UY, Lee HJ, Cho SH, Choi JW. Study to Facilitate Cadaver Donation. Sejong, Korea: Korean Ministry of Health and Welfare; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Paik SJ. Proposal to honor and support cadaver donors to facilitate a culture of donation; Public Hearing Fact Sheet on the Study on How to Improve the Honor and Support System for Human Body Donation; November 24, 2023; Seoul, Korea. Seoul, Korea: Korea National Institute for Bioethics Policy; 2023. [Google Scholar]