Abstract

Cladribine tablets (CladT) has been available for therapeutic use in France since March 2021 for the management of highly active relapsing multiple sclerosis (RMS). This high-efficacy disease-modifying therapy (DMT) acts as an immune reconstitution therapy. In contrast to most high-efficacy DMTs, which act via continuous immunosuppression, two short courses of oral treatment with CladT at the beginning of years 1 and 2 of treatment provide long-term control of MS disease activity in responders to treatment, without the need for any further pharmacological treatment for several years. Although the labelling for CladT does not provide guidance beyond the initial treatment courses, real-world data on the therapeutic use of CladT from registries of previous clinical trial participants and patients treated in routine practice indicate that MS disease activity is controlled for a period of years beyond this time for a substantial proportion of patients. Moreover, this clinical experience has provided useful information on how to initiate and manage treatment with CladT. In this article we, a group of expert neurologists from France, provide recommendations on the initiation of CladT in DMT-naïve patients, how to switch from existing DMTs to CladT for patients with continuing MS disease activity, how to manage patients during the first 2 years of treatment and finally, how to manage patients with or without MS disease activity in years 3, 4 and beyond after initiating treatment with CladT. We believe that optimisation of the use of CladT beyond its initial courses of treatment will maximise the benefits of this treatment, especially early in the course of MS when suppression of focal inflammation in the CNS is a clinical priority to limit MS disease progression.

Keywords: Multiple sclerosis, Cladribine tablets, Disease-modifying therapy, Holistic management

Key Summary Points

| Cladribine tablets (CladT) acts as an immune reconstitution therapy in contrast to most high-efficacy DMTs, which act via continuous immunosuppression |

| The labelling for CladT does not provide guidance beyond the initial 4 years following the initiation of treatment, but real-world data indicate that MS disease activity is controlled for a period of years beyond this time for a substantial proportion of patients |

| Clinical experience has provided useful information on how to initiate and manage treatment with CladT |

| In this article, a group of expert neurologists from France provide recommendations on the initiation of CladT, how to switch from existing DMTs to CladT, and how to manage patients during the first 2 years of treatment and in years 3, 4 and beyond after initiating treatment with CladT |

Introduction

Recent years have seen the introduction of multiple new high-efficacy disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) for the management of relapsing multiple sclerosis (RMS) [1]. This development has increased the potential for personalised management of the individual patient with RMS, while simultaneously adding complexity to the selection of the most appropriate management regimen. When considering either the initiation of a new DMT or a switch to a different DMT, the neurologist must both consider the present situation (e.g. the patient’s MS disease history, comorbidities, lifestyle and personal preferences) and anticipate possible future developments to ensure an optimal balance of efficacy and safety over time (e.g. based on prognostic factors or whether the patient plans on starting a family). Finally, the physician must be ready to intervene in the event of unacceptable MS disease activity to amend the regimen and re-establish control of the disease.

DMTs for the management of MS can be categorised in various ways. For example, platform DMTs, such as interferons, glatiramer acetate, teriflunomide, dimethyl fumarate (DMF) or diroximel fumarate, are products with either no (in the case of immunomodulators) or a low level of immune suppression with moderate efficacy, while high-efficacy DMTs usually act via continuous immunosuppression [2, 3]. The escalation model of therapy for RMS often involves initial prescription of a platform agent, followed by a switch to a high-efficacy DMT if MS disease activity is not controlled [4]. The early use of high-efficacy DMT is increasingly common, especially for patients presenting with highly active MS. The European labelling (SmPC) for some high-efficacy DMTs supports their use as the first-line treatment for RMS, without the need to demonstrate high disease activity. The increasing choice of DMTs now available and their different clinical characteristics and mechanisms of action have provided greater opportunity for individualisation of patient care while increasing the complexity facing the physician and patient when agreeing the most appropriate DMT regimen to adopt.

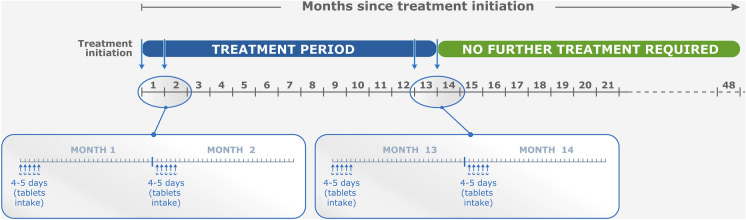

Immune reconstitution therapy (IRT) is another high-efficacy therapeutic choice for the management of RMS. IRT involves administration of short and distant courses of treatment, followed by a period free of MS disease activity that can persist for years in most treated patients [2, 5]. Healthcare professionals in some countries, including France, have limited experience in applying this relatively new modality of care to their patients with RMS. Cladribine tablets (CladT) is the principal available IRT in France (where the authors practise medicine). Use of other agents which may act via an IRT-like mechanism is restricted in France because of safety concerns (alemtuzumab [6]); they are little used in practice (mitoxantrone or autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation) or are given continuously to produce a state of continuous immunosuppression (anti-CD20 agents, such as ocrelizumab, ofatumumab or rituximab [5]). Figure 1 summarises the posology of CladT from its European labelling [7, 8]. Current guidelines have provided a practical framework for the therapeutic use of CladT over the first 2 years of treatment [9], and data from real-world studies have shown generally similar efficacy and safety outcomes in real-world studies compared with the earlier randomised trials [10–17]. Follow-up of patients treated with CladT beyond 4 years after the first administration was limited at that time, and today we have few real-world studies that follow patients for this long (described below); moreover, it is notable that while giving explicit instructions for the initiation of CladT, like other DMTs, the label provides no guidance on how to manage the patient beyond the duration of the registration trial.

Fig. 1.

Overview of cladribine tablet posology for relapsing multiple sclerosis patients. aCladribine tablets is given as two treatment courses 1 year apart [7]. Inset shows details of one treatment course: blue arrows show treatment days at the beginning of month 1 and month 2 (5 treatment days are shown for each month, but in practice this could be 4 or 5 days, depending on body weight). bEuropean Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC). Compiled from information presented in the European SmPC for cladribine tablets [7] and aadapted here from reference [8] under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0)

We published recommendations on the place of IRT (effectively CladT, as described above) in 2023, focusing on the types of patients with RMS who might be considered for this therapy [9], supported by a further comprehensive review of the safety and tolerability of CladT [8]. As real-world therapeutic experience with CladT has increased, the longer-term therapeutic profile of this agent becomes better understood. In this review, we update and expand our previous recommendations on the holistic management of people with RMS treated with CladT, from the initial prescription to long-term treatment beyond years 3 or 4 of therapy.

Data Sources

The content of the article is based on the clinical experience of the authors (expert clinical neurologists based in France), local guidelines (for some aspects of holistic management such as treatment switches and MRI follow-up) and information published in the clinical literature. Published articles for review were identified via a search of PubMed and EMbase, as well as data presented at recent international congresses, focusing on the therapeutic use of CladT, especially beyond the 2nd year of treatment. We checked that data presented in abstracts had not been superseded by full-length publications: where this was not so we included contributions to congresses within our evidence base to capture the most up-to-date clinical information. The searches confirmed that published data on the use of CladT in people with MS (PwMS) are limited largely to 4 years of treatment, with few data for treatment beyond year 5. The recommendations presented here for long-term treatment with CladT were developed at a series of meetings where consensus was achieved through discussion (no formal consensus procedure was used) and represent the experts’ positions on best clinical practice while waiting for new data to ensure optimum patient care.

This review article is based on previously conducted studies and the clinical expertise of the authors in treating patients with RMS. No new clinical studies were performed by the authors. No patient-specific efficacy or safety data were reported; therefore, institutional review board (IRB)/ethics approval was not required.

Initiation of Treatment with Cladribine Tablets for the Management of Relapsing Multiple Sclerosis

General Principles Relating to the Prescription of Immune Reconstitution Therapy for RMS

A key aspect of the treatment consultation is to match the DMT with the patient’s preferences, expectations and lifestyle [18]. First, CladT is a high-efficacy DMT, as shown in the pivotal CLARITY study and in real-world studies [19, 20], and is therefore suitable for patients with high MS disease activity. Successful administration of IRT results in a lack of continuous treatment beyond the initial treatment courses, which may be attractive to patients who find the administration, monitoring and side effects of continuous immunosuppression burdensome or adherence to continuous treatment regimens challenging (see below). A period of (potentially) years without continuous administration also provides an opportunity for the person with MS to conceive and deliver a child if they are prepared to wait out the labelled 6-month post-treatment washout period (for CladT) before a pregnancy should occur [21]. Intention to pursue a family in the near future may be a reason to switch between a DMT that is contraindicated during pregnancy to IRT [21].

Finally, CladT is a well-tolerated oral therapy, which may be important for some patients and may help to support adherence to the treatment regimen (fingolimod and ponesimod are also administered orally every day, but other high-efficacy DMTs are monoclonal antibodies administered by injection or infusion). Indeed, for a responder to CladT, the issue of adherence disappears once the Year 1 and 2 courses of treatment have been taken, as no regular administrations of treatment are needed. Support programmes are available in a number of countries to optimise adherence to the year 2 course, which is high in real-world practice [22, 23]. Data from the MSBase registry showed that PwMS have a longer time-to-treatment discontinuation with CladT compared to other oral therapies [24]. Consistent with these observations, scores from validated instruments to measure quality of life and patient satisfaction are generally high during treatment of RMS with CladT [25–27].

Cladribine Tablets as the First Disease-Modifying Therapy

The European SmPC for CladT contains a therapeutic indication “for the treatment of adult patients with highly active relapsing multiple sclerosis (MS) as defined by clinical or imaging features” [7]. While it refers to the results of the CLARITY study to describe the clinical efficacy of CladT in RMS, including the post hoc analysis in patients with high disease activity prior to the study [28], there is no clear definition of “highly active” RMS in the SmPC for CladT. Similarly, there is no clear consensus for defining “highly active relapsing RMS” in the clinical literature [18]. In addition, the absolute lymphocyte count (ALC) needs to be “normal” (not defined further) before the first dose of CladT [7].

We support the pragmatic approach outlined in the SmPC for the DMT-naïve patient as it is consistent with the ultimate goal of management or RMS, which is to prevent the accumulation of disability. A number of observational studies have demonstrated lower long-term progression of disability in subjects who received high-efficacy DMT earlier rather than later [4, 29–34]. Early administration of CladT fits with the need to suppress focal inflammation early in the clinical course of RMS, as this is a key driver of MS disease progression at this time [18].

The criteria for prescribing CladT as initial therapy may become broader in future as the evidence base for this approach increases, including from real-world studies [20, 35]. Such a change in approach would be consistent with increasing use of high-efficacy DMTs at earlier stages of the evolution of MS compared with the standard escalation approach where a switch to a high-efficacy DMT occurs only after the patient has been exposed to further MS disease activity [36], including for treatment-naïve individuals [37]. The early intensive therapy approach has been shown in observational studies to protect patients from clinical and radiological MS events, progression of disability or conversion to secondary progression of MS [32, 38–40]. Current European guidance for the management of RMS does not restrict the choice of DMT to a platform agent for a patient with early, highly active MS disease activity [9].

Switching to Cladribine Tablets from Other Disease-Modifying Therapies

Switching Between DMTs: General Principles

It is rational to switch to a high-efficacy DMT when MS disease activity has recurred, including clinical or radiological activity. Similarly, a lateral switch or switch to a high-efficacy DMT may also be considered if unacceptable tolerability or safety concerns have arisen during treatment with a platform DMT. The short-term goal is to suppress inflammation in the CNS, as this contributes to relapses and disease progression primarily early in the course of MS [41–44]. There is substantial evidence that earlier rather than later use of high-efficacy DMTs improves long-term disability outcomes in populations with RMS, as described above. However, “disability” is too often conflated with “motor physical handicap”, i.e. EDSS score progression. More research is needed to define the effects of different aspects of MS progression, such as cognitive function, mood/affect and patient-reported outcomes relating to fatigue, difficulties at work and impact on daily life [45–48].

Prevention of reactivation or exacerbation of MS disease activity is paramount when switching between DMTs, so that a switch must achieve a balance between prompt restoration of protection against relapses while preserving safety. The Société Française de la Sclérose en Plaques (SFSEP) published guidance in this area in 2021 [49]. Switching from a platform therapy (interferons, glatiramer acetate, teriflunomide or DMF) can be done immediately, without the need for a washout period between treatments. The same guidance should be considered for diroximel fumarate, which was not available at time the SFSEP guidance was published. One caveat to this approach is the need to ensure that absolute lymphocyte count is > 800/mm3 after withdrawal of DMF, as persistent lymphocytopenia has been observed for as long as 5 years after withdrawal of this agent, with the possibility of low absolute lymphocyte counts being erroneously attributed to the effects of the subsequent treatment [50–52]. A 3-month washout period should follow withdrawal of ocrelizumab, and a 6-month washout period should follow withdrawal of mitoxantrone, based on local SFSEP guidelines in France [49]. Fingolimod and natalizumab differ from other high-efficacy DMTs in that withdrawal of these agents has been observed to provoke severe and potentially disabling reactivations of MS disease activity, often beginning 6–8 weeks (fingolimod) or around 3 months (natalizumab) following the cessation of treatment [53–58]. The SFSEP therefore recommend that a washout period of 1 month should follow withdrawal of these DMTs to facilitate prompt reestablishment of therapeutic cover with the new DMT. Moreover, as per SmPC recommendation, a baseline MRI scan should be performed up to 3 months before initiating CladT initiation to exclude the presence of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) or other serious infections before starting treatment, especially when switching from another DMT [7].

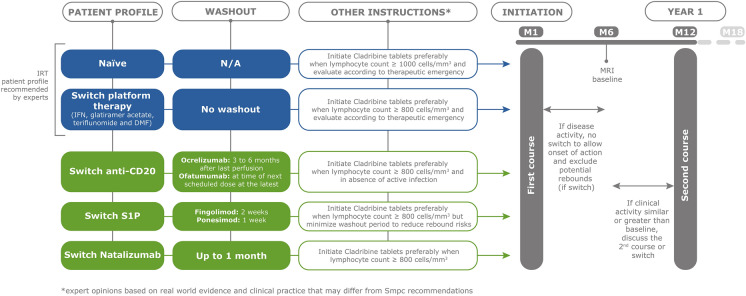

Figures 2 summarises recommendations for switching from an existing DMT to CladT, and these are explained below.

Fig. 2.

Overview of the expert opinion on the management of patients treated with cladribine tablets at time of initiation according to patient profile regarding prior DMT and follow-up recommendation during 1st year of treatment. *Expert opinion based on real-world evidence and clinical practice that may differ from recommendations in the European Summary of Product Characteristics [7]. DMF dimethyl fumarate, IFN interferon, IRT immune reconstitution therapy, M1, M6, etc., refers to months, MRI magnetic resonance imaging, N/A not applicable, S1P sphingosine-1-phosphate inhibitor(s)

Switching to Cladribine Tablets from a Platform DMT

We support the recommendation of the SFSEP in that treatment with CladT can begin immediately after withdrawal of interferon, glatiramer acetate, DMF or teriflunomide. While the European Summary of Product Characteristics for CladT [7] states that ALC should be > 1000/mm3 before initial administration of CladT, this will be problematic for some patients previously receiving DMT, especially DMF and fingolimod as per above. We suggest that minimising the delay before establishing the new treatment is important. Our recommendation, based on expert opinion, is that it is preferable to initiate CladT when ALC is > 800/mm3 and that the individual patient’s level of MS disease activity should be considered carefully before delaying the switch. We note that this same consideration would apply to the prescription of any new DMT and not only CladT.

Switching to Cladribine Tablets from an Anti-CD20 Agent

Ocrelizumab has a dosing interval of 6 months and we recommend that CladT should be started 3–6 months after the last dose (also based on local SFSEP guidance [49]) to ensure no loss of effectiveness of DMT. Ofatumumab is administered monthly and CladT may be initiated no later than time of the next scheduled dose after cessation of ofatumumab.

Switching to Cladribine Tablets from Leucocyte Anti-trafficking Agents (natalizumab or S1P modulators)

A washout period post-natalizumab of up to 1 month is recommended to reduce the risk of disease reactivation. The onset of action of CladT is rapid (as little as 2 months [59]); thus, minimizing the wash-out period should minimise the risk of rebound MS disease activity. As mentioned previously and as per label recommendations [7], it is important to conduct an MRI scan during this period and prior to CladT initiation to rule out any early or asymptomatic PML. Minimising the washout period duration rather than waiting for an ALC threshold is preferable when switching from an S1P modulator: we recommend starting CladT as soon as 2 weeks after withdrawing fingolimod and 1 week after withdrawing ponesimod (although further data on the short-term recovery of ALC after discontinuing these agents would be helpful to identify a time when sufficient lymphocytes are likely to have been released to support the mechanism of IRT after withdrawing these agents). For completeness, we do not provide a recommendation on the use of ozanimod because it is neither available for prescription nor reimbursed in France.

It is important to remember that patients will seek to switch their DMT from these agents for a range of reasons, including JCV positivity on natalizumab (high risk of rebound), for MS disease activity unrelated to this, or to avoid continuous treatment, as discussed elsewhere in this article. The physician's knowledge and experience are therefore essential for achieving the best overall treatment decision.

Patient Management after Initiation of Cladribine Tablets

Year 1 (Period of Administration of Cladribine Tablets, Fig. 2)

The nadir for ALC after a course of CladT occurs at about 8 weeks in year 1, with gradual recovery thereafter for most patients [60]. ALC should be monitored 2 and 6 months after initiation of treatment, with continued monitoring if ALC is < 500/mm3, according to the drug’s European label [7]. Data from the MAGNIFY study registry showed that the onset of action of CladT is rapid, with significant reduced risk of MRI lesions occurring from the 2nd month of treatment onwards, and efficacy continues to increase over the first 6 months [59]. Accordingly, a rebaselining MRI is useful 3–6 months after starting CladT and a routine annual MRI thereafter. No data are available to provide guidance on whether to include a spinal cord MRI, and this will be done or not according to practice at local centres.

It is important to note that the full efficacy of CladT is achieved only when the second (year 2) course of treatment has been given [61–64]. Accordingly, physicians must use their clinical judgement as to whether the appearance of some MS disease activity in year 1 represents a serious reactivation of MS disease activity that requires a treatment switch, e.g. if the activity is similar to or higher than that seen on the previous DMT. Residual MS disease activity may persist for some months beyond the switch to CladT. This situation does not necessarily require a switch from CladT to another high-efficacy DMT before administration of the year 2 course of CladT. In the CLARITY study, 14% of patients demonstrated MS disease activity after the first course of CladT, but 61% of these patients demonstrated no further MS disease activity in year 2, following the second course. Real-world evidence suggests that most patients who report MS disease activity during year 1 of treatment do not switch to an alternative DMT, a systematic review of real-world studies with CladT in 3628 people with MS [20] showed that only 2.4% of patients discontinued or switched away from CladT in the 1st year of treatment (Table 1) [14, 65–76]. The phenomenon of MS disease reactivation after withdrawing an S1P inhibitor or natalizumab is a different phenomenon to residual MS disease activity during the time needed for the efficacy of CladT to build. The physician's knowledge and experience is key to decipher residual disease activity from disease reactivation requiring a modification of the therapeutic strategy, as mentioned above.

Table 1.

Summary of published cohorts reporting patients treated with cladribine tablets who discontinued or switched treatment during year 1, prior to the second course of cladribine tablets

| References | Country | No. of patients | No. of discontinuations or switches [N (%)] |

|---|---|---|---|

| [65] | Canada | 111 | 0 |

| [66] | Italy | 60 | 1 (1.7) |

| [67] | Spain | 85 | 5 (5.9) |

| [68] | Spain | 88 | 2 (2.3) |

| [69] | Czechia | 436 | 12 (2.8) |

| [70] | USA | 616 | 6 (1.0) |

| [71] | Germany | 270 | 3 (1.1) |

| [72] | Sweden | 140 | 5 (3.5) |

| [73] | United Arab Emirates | 88 | 1 (1.1) |

| [14] | Finland | 179 | 4 (3) |

| [74] | International | 610 | 1 (0.2) |

| [75] | Internationala | 782 | 31 (4.0) |

| [76] | Portugal | 182 | 13 (7.1) |

| Totals: | 3628 | 87 (2.4) | |

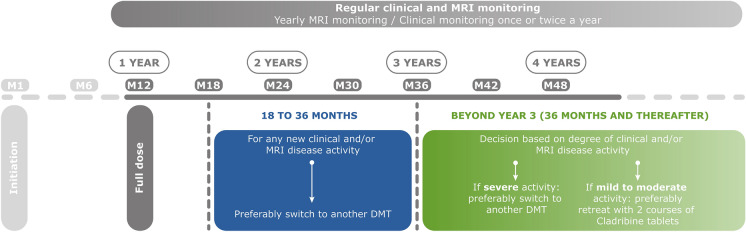

Beyond the Second Course of Cladribine Tablets (Fig. 3)

Fig. 3.

Overview of expert opinion on patient management after taking a full dose of cladribine tablets, year 1 and beyond. DMT disease-modifying treatment, M6, M12, etc., refers to months, MRI magnetic resonance imaging

It is important to note that the lack of need for continuous drug administration with an IRT in a patient who responds to treatment does not equate to a lack of need for general clinical management. An MRI for rebaselining followed by annual MRI is recommended, as per recommendations from the Observatoire Français de la Sclérose En Plaques (OFSEP). In addition, clinical monitoring may continue annually or every 6 months, depending on local practice and whether residual MS disease activity is occurring (see below).

The CLASSIC-MS registry is following up patients originally enrolled in the CLARITY study and its extension. An analysis of these data (N = 435) showed that 63% of patients did not use a subsequent DMT for at least 4 years after the second course of CladT, 48.0% showed no evidence of disease reactivation, and 33% met both of these criteria [77]. More than half of the CLASSIC-MS population (53%) did not receive another DMT during a median follow-up of 10.9 years since the last dose of CladT. Data from the CLARINET-MS registry showed that 66.2% and 57.2% were relapse free at 36 and 60 months, respectively, after the last dose of cladribine tablets (i.e. about 4 years and 6 years after the end of treatment, respectively) [78]. Long-term suppression of MS disease activity beyond the 4-year period studied in the CLARITY trial and its extension is therefore clearly possible. One real-world study showed that 26% of people with MS treated with CladT demonstrated recurrent MS disease activity during a median follow-up period of 4.5 years and that this was associated with higher MRI activity at baseline and receipt of a lower than indicated dose for the second course of CladT [79]. Another registry-based study found that 74% of a Clad-T-treated population achieved NEDA-2 during year 4 of treatment of a population with highly active MS [80].

There is no need for retreatment with CladT for a patient with no MS disease activity in years 3, 4 and beyond. The reappearance of MS disease activity should not be tolerated from 6 months after the second course of CladT onwards when lymphocytes will have largely repopulated and immune reconstitution should have occurred. As shown in Fig. 3, any MS disease activity in the latter part of year 2 or in year 3 from the initiation of treatment should prompt consideration of a switch to an alternative high-efficacy DMT such as monoclonal antibodies, which may present a higher level of efficacy [81]. Beyond year 3, the appearance of severe disease activity should lead to considering a switch to another high-efficacy DMT, while patients with mild-to-moderate MS disease activity at this time may be candidates for treatment with a further two annual courses of CladT. Switching to another DMT from CladT is straightforward in years 2 and 3, as lymphocytes will have recovered from the second course, and no washout period is required before initiating a new DMT. These recommendations are largely aligned with expert opinion from Germany [82].

Data regarding retreatment after year 4 remain limited, especially regarding the implications for safety of additional courses of CladT, and the current evidence base does not support systematic retreatment after year 4 for patients, even with poor prognostic factors. Further real-world data are required to address this question: the CLIP-5 and CLOBAS observational cohorts will evaluate the efficacy and safety of CladT at 5 and 6 years following initial administration, respectively [20]. Biomarkers are needed to assist prediction of longer-term outcomes in patients treated with CladT (and, indeed, for all DMTs). Data from the MAGNIFY-MS cohort will examine the relationships between early changes in immune cells and longer-term treatment outcomes in patients who received CladT for RMS [11]. Effects on memory B cells after CladT have emerged as an interesting potential early marker of efficacy in MAGNIFY-MS and elsewhere [83, 84]. Annual immunophenotyping to monitor memory B cells may therefore provide another predictive marker of future MS disease activity [85, 86]. CladT has been shown to reduce serum neurofilament light chain (sNfL), a biomarker of axonal damage in MS, although further validation of this biomarker is needed to predict who may need re-treatment with CladT [87].

Other current (published in 2023) expert opinion for the management of CladT-treated people with MS who develop moderate MS disease activity after year 4 recommends either 1–2-year courses of CladT or an alternative high-efficacy DMT [88–92]. All stress the importance of a thorough, individualised risk/benefit consideration before deciding on the future management policy at this time.

Predicting Future MS Disease Activity or Progression of Disability

Regarding the considerations on switching DMTs above, it would be ideal if patients at risk of needing treatment intensification could be identified on the basis of their clinical presentation. Scores derived from clinical and radiological findings in patients with multiple sclerosis (e.g. based on the MAGNIMS or RIO cohorts, or others such as the Risk of Ambulatory Disability score) have been used to predict the future occurrence of disease activity during treatment with interferonβ or glatiramer acetate [93–95] to predict progression of disability during treatment with interferons [96–99], glatiramer acetate [99], natalizumab [99], teriflunomide [100], DMF [101] or an S1P modulator [99–101] or to predict the likelihood of a sub-optimal response following a switch from platform DMTs to fingolimod or natalizumab [102]. Another study used a range of these scores to predict future disability after 1 year of treatment with various DMTs [103]. An elevation in the level of sNfL is another emerging clinical biomarker for an imminent deterioration in clinical status in populations with MS [100]. These approaches should be validated in different populations of patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis, for example those managed in different countries with different healthcare systems [104].

Conclusions

The use of CladT is now established within the management of RMS, particularly earlier in the course of therapy when suppression of focal inflammation in the CNS is a clinical priority to limit MS disease progression. Continued follow-up of patients previously enrolled in randomised evaluations of CladT, together with real-world data from routine clinical practice, has provided new information on the efficacy, safety and optimal application of this treatment. Nevertheless, current published data are almost completely limited to 4 years of treatment, with only a handful of data available beyond year 5. In this article, experts in the management or RMS in France have addressed this gap in knowledge and provide practical recommendations on the management of people with MS with CladT through 4 years and beyond.

A previous publication has explored the profiles of people with MS who may respond well to IRT in general and CladT in particular (essentially those relatively early in the MS disease process where focal inflammation is a key driver of disease progression, for whom IRT/CladT may delay the need for continuous immunosuppression) [9]. However, we have been clear that there is a lack of hard clinical evidence to support the management of a patient with MS disease activity 4 years after starting CladT, and this is why we have sought to communicate our expert opinion in this article. As described above, the choice faced by a neurologist for a CladT-treated person with MS under these circumstances is effectively to re-treat with CladT or to switch to another high-efficacy DMT such as monoclonal antibodies. Lack of information on the relative consequences of this choice reflects another important gap in our evidence base and a necessary limitation of our approach. As a result, we have not sought to provide specific recommendations on which road to take. CladT and other high-efficacy DMTs are not equivalent: all of these drugs vary in their efficacy, safety and tolerability profiles and management decisions for patients with RMS must depend ultimately on the individual clinical presentation of the patient together with their personal needs and preferences. Our recommendations here provide pragmatic guidance on the use of CladT for a range of patient types within this context.

Acknowledgements

Medical Writing and Editorial Assistance

A medical writer (Dr Mike Gwilt, GT Communications) provided editorial assistance, funded by Merck Serono SAS, Lyon, France, an affiliate of Merck KGaA.

Author Contributions

Jonathan Ciron, Bertrand Bourre, Giovanni Castelnovo, Anne Marie Guennoc, Jérôme De Sèze, Ali Frederic Ben Amor, Carine Savarin and Patrick Vermersch contributed equally to the conception, design, content and interpretation of data in the article, participated in its drafting and critical revision for intellectual content, approved the final version for submission and acknowledge that they are accountable for all aspects of the article.

Funding

Merck Serono SAS, Lyon, France, an affiliate of Merck KGaA (CrossRef Funder ID: 10.13039/100009945) funded editorial support (see below) and the journal’s Rapid Service Fee.

Data Availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

Jonathan Ciron has received personal compensation for consulting, serving on a scientific advisory board, speaking, or other activities with Biogen, Novartis, Merck, Sanofi, Roche, Celgene-BMS, Alexion, and Horizon Therapeutics. Bertrand Bourre has received consulting and lecturing fees, travel grants, and unconditional research support from Alexion, Biogen, Horizon, Janssen, Merck, Novartis, Roche, Sandoz, and Sanofi. Giovanni Castelnovo received fees for consulting and speaking from Biogen, Abbvie, Merck, Novartis, Roche, Sanofi Genzyme, Merz, Celgene BMS. Anne-Marie Guennoc has received personal compensation for consulting, serving on a scientific advisory board, speaking, or other activities with Biogen, Novartis, Merck, Sanofi, Roche. Jerome De Sèze has received fees for consultancy, advisory board and clinical trials from UCB, Novartis, Biogen, Merck, Teva, Genzyme/ Sanofi, Roche, Alexion, BMS/Celegene, Janssen, Horizon Therapeutics. At the time of the expert meeting, Ali-Frederic Ben-Amor was an employee of Ares-Trading SA Eysins, Switzerland, an affiliate of Merck KGaA. Carine Savarin is an employee of Merck Santé S.A.S., Lyon, France, an affiliate of Merck KGaA. Patrick Vermersch received honoraria for contributions to meetings from Biogen, Sanofi-Genzyme, Novartis, Teva, Merck, Roche, Imcyse, AB Science and BMS-Celgene, and research support from Novartis, Sanofi-Genzyme and Merck.

Ethical Approval

This review article is based on previously conducted studies and the clinical expertise of the authors in treating patients with RMS. No new clinical studies were performed by the authors. No patient-specific efficacy or safety data were reported; therefore, institutional review board (IRB)/ethics approval was not required.

References

- 1.Amin M, Hersh CM. Updates and advances in multiple sclerosis neurotherapeutics. Future Med. 2022 doi: 10.2217/nmt-2021-0058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.AlSharoqi IA, Aljumah M, Bohlega S, et al. Immune reconstitution therapy or continuous immunosuppression for the management of active relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis patients? a narrative review. Neurol Ther. 2020;9:55–66. doi: 10.1007/s40120-020-00187-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alroughani R, Inshasi JS, Deleu D, et al. An overview of high-efficacy drugs for multiple sclerosis: Gulf region expert opinion. Neurol Ther. 2019;8:13–23. doi: 10.1007/s40120-019-0129-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Casanova B, Quintanilla-Bordás C, Gascón F. Escalation vs. early intense therapy in multiple sclerosis. J Pers Med. 2022;12:119. doi: 10.3390/jpm12010119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sorensen PS, Sellebjerg F. Pulsed immune reconstitution therapy in multiple sclerosis. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2019;12:1756286419836913. doi: 10.1177/1756286419836913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.European Medicines Agency. Lemtrada. Measures to minimise risk of serious side effects of multiple sclerosis medicine Lemtrada. Available at https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/referrals/lemtrada. Accessed 23 Feb 2024.

- 7.European Medicines Agency. Mavenclad. Summary of Product Characteristics. Available at https://www.ema.europa.eu/documents/product-information/mavenclad-epar-product-information_en.pdf. Accessed 23 Feb 2024.

- 8.Clavelou P, Castelnovo G, Pourcher V, et al. Expert narrative review of the safety of cladribine tablets for the management of relapsing multiple sclerosis. Neurol Ther. 2023;12:1457–1476. doi: 10.1007/s40120-023-00496-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Montalban X, Gold R, Thompson AJ, et al. ECTRIMS/EAN Guideline on the pharmacological treatment of people with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2018;24:96–120. doi: 10.1177/1352458517751049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adamec I, Brecl Jakob G, Rajda C, et al. Cladribine tablets in people with relapsing multiple sclerosis: a real-world multicentric study from southeast European MS centers. J Neuroimmunol. 2023;382:578164. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2023.578164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aerts S, Khan H, Severijns D, Popescu V, Peeters LM, Van Wijmeersch B. Safety and effectiveness of cladribine tablets for multiple sclerosis: results from a single-center real-world cohort. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2023;75:104735. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2023.104735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zanetta C, Rocca MA, Meani A, et al. Effectiveness and safety profile of cladribine in an Italian real-life cohort of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis patients: a monocentric longitudinal observational study. J Neurol. 2023;270:3553–3564. doi: 10.1007/s00415-023-11700-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Petracca M, Ruggieri S, Barbuti E, et al. Predictors of cladribine effectiveness and safety in multiple sclerosis: a real-world, multicenter, 2-year follow-up study. Neurol Ther. 2022;11:1193–1208. doi: 10.1007/s40120-022-00364-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rauma I, Viitala M, Kuusisto H, et al. Finnish multiple sclerosis patients treated with cladribine tablets: a nationwide registry study. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2022;61:103755. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2022.103755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Song Y, Wang Y, Wong SL, Yang D, Sundar M, Tundia N. Real-world treatment patterns and effectiveness of cladribine tablets in patients with relapsing forms of multiple sclerosis in the United States. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2023;79:105052. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2023.105052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moser T, Ziemssen T, Sellner J. Real-world evidence for cladribine tablets in multiple sclerosis: further insights into efficacy and safety. Wien Med Wochenschr. 2022;172:365–372. doi: 10.1007/s10354-022-00931-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sorensen PS, Pontieri L, Joensen H, et al. Real-world experience of cladribine treatment in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: a Danish nationwide study. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2023;70:104491. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2022.104491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Sèze J, Suchet L, Mekies C, et al. The place of immune reconstitution therapy in the management of relapsing multiple sclerosis in France: an expert consensus. Neurol Ther. 2023;12:351–369. doi: 10.1007/s40120-022-00430-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giovannoni G, Comi G, Cook S, et al. A placebo-controlled trial of oral cladribine for relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:416–426. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0902533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oreja-Guevara C, Brownlee W, Celius EG, et al. Expert opinion on the long-term use of cladribine tablets for multiple sclerosis: systematic literature review of real-world evidence. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2023;69:104459. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2022.104459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alroughani R, Inshasi J, Al-Asmi A, et al. Disease-modifying drugs and family planning in people with multiple sclerosis: a consensus narrative review from the Gulf Region. Neurol Ther. 2020;9:265–280. doi: 10.1007/s40120-020-00201-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brownlee W, Amin A, Ashton L, Herbert A. Real-world use of cladribine tablets (completion rates and treatment persistence) in patients with multiple sclerosis in England: the CLARENCE study. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2023;79:104951. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2023.104951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adveva. Available at https://www.adveva.co.uk/en/about-mavenclad/getting-to-know-mavenclad.html. Accessed 23 Feb 2024.

- 24.Spelman T, Ozakbas S, Alroughani R, et al. Comparative effectiveness of cladribine tablets versus other oral disease-modifying treatments for multiple sclerosis: results from MSBase registry. Mult Scler. 2023;29:221–235. doi: 10.1177/13524585221137502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brochet B, Solari A, Lechner-Scott J, et al. Improvements in quality of life over 2 years with cladribine tablets in people with relapsing multiple sclerosis: The CLARIFY-MS study. Mult Scler. 2023;29:1808–1818. doi: 10.1177/13524585231205962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Inshasi J, Farouk S, Shatila A, et al. Multicentre observational study of treatment satisfaction with cladribine tablets in the management of relapsing multiple sclerosis in the Arabian Gulf: the CLUE Study. Neurol Ther. 2023;12:1309–1318. doi: 10.1007/s40120-023-00497-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rau D, Müller B, Übler S. Evaluation of patient-reported outcomes in patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis treated with cladribine tablets in the CLAWIR study: 12-month interim analysis. Adv Ther. 2023;40:5547–5556. doi: 10.1007/s12325-023-02682-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Giovannoni G, Soelberg Sorensen P, Cook S, et al. Efficacy of cladribine tablets in high disease activity subgroups of patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis: a post hoc analysis of the CLARITY study. Mult Scler. 2019;25:819–827. doi: 10.1177/1352458518771875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wiendl H, Gold R, Berger T, et al. Multiple Sclerosis Therapy Consensus Group (MSTCG): position statement on disease-modifying therapies for multiple sclerosis (white paper) Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2021;14:17562864211039648. doi: 10.1177/17562864211039648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rojas JI, Patrucco L, Alonso R, et al. Effectiveness and safety of early high-efficacy versus escalation therapy in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis in Argentina. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2022;45:45–51. doi: 10.1097/WNF.0000000000000503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Filippi M, Danesi R, Derfuss T, et al. Early and unrestricted access to high-efficacy disease-modifying therapies: a consensus to optimize benefits for people living with multiple sclerosis. J Neurol. 2022;269:1670–1677. doi: 10.1007/s00415-021-10836-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Simonsen CS, Flemmen HØ, Broch L, et al. Early high efficacy treatment in multiple sclerosis is the best predictor of future disease activity over 1 and 2 years in a Norwegian population-based registry. Front Neurol. 2021;12:693017. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2021.693017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harding K, Williams O, Willis M, et al. Clinical outcomes of escalation vs early intensive disease-modifying therapy in patients with multiple sclerosis. JAMA Neurol. 2019;76:536–541. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.4905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brown JWL, Coles A, Horakova D, et al. Association of initial disease-modifying therapy with later conversion to secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. JAMA. 2019;321:175–187. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.20588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Freedman MS, Leist TP, Comi G, et al. The efficacy of cladribine tablets in CIS patients retrospectively assigned the diagnosis of MS using modern criteria: Results from the ORACLE-MS study. Mult Scler J Exp Transl Clin. 2017;3:2055217317732802. doi: 10.1177/2055217317732802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Filippi M, Amato MP, Centonze D, et al. Early use of high-efficacy disease-modifying therapies makes the difference in people with multiple sclerosis: an expert opinion. J Neurol. 2022;269:5382–5394. doi: 10.1007/s00415-022-11193-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Freeman L, Longbrake EE, Coyle PK, Hendin B, Vollmer T. High-efficacy therapies for treatment-naïve individuals with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. CNS Drugs. 2022;36:1285–1299. doi: 10.1007/s40263-022-00965-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.He A, Merkel B, Brown JWL, et al. Timing of high-efficacy therapy for multiple sclerosis: a retrospective observational cohort study. Lancet Neurol. 2020;19:307–316. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(20)30067-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Buron MD, Chalmer TA, Sellebjerg F, et al. Initial high-efficacy disease-modifying therapy in multiple sclerosis: a nationwide cohort study. Neurology. 2020;95:e1041–e1051. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000010135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Spelman T, Magyari M, Piehl F, et al. Treatment escalation vs immediate initiation of highly effective treatment for patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: data from 2 different national strategies. JAMA Neurol. 2021;78:1197–1204. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2021.2738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Popescu BF, Pirko I, Lucchinetti CF. Pathology of multiple sclerosis: where do we stand? Continuum (Minneap Minn) 2013;19(4 Multiple Sclerosis):901–921. doi: 10.1212/01.CON.0000433291.23091.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gallo P, Van Wijmeersch B, ParadigMS Group Overview of the management of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis and practical recommendations. Eur J Neurol. 2015;22(Suppl 2):14–21. doi: 10.1111/ene.12799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Alroughani R, Boyko A. Pediatric multiple sclerosis: a review. BMC Neurol. 2018;18:27. doi: 10.1186/s12883-018-1026-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hughes J, Jokubaitis V, Lugaresi A, et al. Association of inflammation and disability accrual in patients with progressive-onset multiple sclerosis. JAMA Neurol. 2018;75:1407–1415. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.2109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Morrow SA, Riccio P, Vording N, Rosehart H, Casserly C, MacDougall A. A mindfulness group intervention in newly diagnosed persons with multiple sclerosis: a pilot study. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2021;52:103016. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2021.103016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Correale J, Peirano I, Romano L. Benign multiple sclerosis: a new definition of this entity is needed. Mult Scler. 2012;18:210–218. doi: 10.1177/1352458511419702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Renner A, Baetge SJ, Filser M, Penner IK. Working ability in individuals with different disease courses of multiple sclerosis: factors beyond physical impairment. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2020;46:102559. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2020.102559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.He A, Spelman T, Manouchehrinia A, Ciccarelli O, Hillert J, McKay K. Association between early treatment of multiple sclerosis and patient-reported outcomes: a nationwide observational cohort study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2023;94:284–289. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2022-330169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bigaut K, Cohen M, Durand-Dubief F, et al. How to switch disease-modifying treatments in multiple sclerosis: guidelines from the French Multiple Sclerosis Society (SFSEP) Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2021;53:103076. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2021.103076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wood CH, Robertson NP, Htet ZM, Tallantyre EC. Incidence of persistent lymphopenia in people with multiple sclerosis on dimethyl fumarate. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2022;58:103492. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2022.103492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Caldito NG, O'Leary S, Stuve O. Persistent severe lymphopenia 5 years after dimethyl fumarate discontinuation. Mult Scler. 2021;27(8):1306–1308. doi: 10.1177/1352458520988149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Borrelli S, Mathias A, Goff GL, Pasquier RD, Théaudin M, Pot C. Delayed and recurrent dimethyl fumarate induced-lymphopenia in patients with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2022;63:103887. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2022.103887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Malpas CB, Roos I, Sharmin S, et al. Multiple sclerosis relapses following cessation of fingolimod. Clin Drug Investig. 2022;42:355–364. doi: 10.1007/s40261-022-01129-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Roos I, Malpas C, Leray E, et al. Disease reactivation after cessation of disease-modifying therapy in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2022;99:e1926–e1944. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000201029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hellwig K, Tokic M, Thiel S, et al. Multiple sclerosis disease activity and disability following cessation of fingolimod for pregnancy. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2023;10:e200126. doi: 10.1212/NXI.0000000000200110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Callens A, Leblanc S, Le Page E, et al. Disease reactivation after fingolimod cessation in Multiple Sclerosis patients with pregnancy desire: a retrospective study. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2022;66:104066. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2022.104066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Prosperini L, Kinkel RP, Miravalle AA, Iaffaldano P, Fantaccini S. Post-natalizumab disease reactivation in multiple sclerosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2019;12:1756286419837809. doi: 10.1177/1756286419837809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Auer M, Zinganell A, Hegen H, et al. Experiences in treatment of multiple sclerosis with natalizumab from a real-life cohort over 15 years. Sci Rep. 2021;11:23317. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-02665-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.de Stefano N, Barkhof F, Montalban X, et al. Early reduction of MRI activity during 6 months of treatment with cladribine tablets for highly active relapsing multiple sclerosis: MAGNIFY-MS. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2022;9:e1187. doi: 10.1212/NXI.0000000000001187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Comi G, Cook S, Giovannoni G, et al. Effect of cladribine tablets on lymphocyte reduction and repopulation dynamics in patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2019;29:168–174. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2019.01.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.De Stefano N, Sormani MP, Giovannoni G, et al. Analysis of frequency and severity of relapses in multiple sclerosis patients treated with cladribine tablets or placebo: the CLARITY and CLARITY Extension studies. Mult Scler. 2022;28:111–120. doi: 10.1177/13524585211010294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Comi G, Cook SD, Giovannoni G, et al. MRI outcomes with cladribine tablets for multiple sclerosis in the CLARITY study. J Neurol. 2013;260:1136–1146. doi: 10.1007/s00415-012-6775-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schippling S, Sormani MP, De Stefano N, et al. CLARITY: an analysis of severity and frequency of relapses in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis treated with cladribine tablets or placebo. Mult Scler J. 2018;24(S2):258. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yamout B, Giovannoni G, Magyari M, et al. Preservation of relapse-free status in year 2 of treatment with cladribine tablets by relapse-free status in year 1. Eur J Neurol. 2020;27(Suppl. 1):482. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bain J, Oh J, Jones A, et al. Early real-world safety, tolerability, and efficacy of cladribine tablets: a single center experience. Mult Scler. 2020;26(3 Suppl):274. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Barbuti E, Ianniello A, Nistri R, et al. Real world experience with cladribine at S Andrea hospital of Rome. J Neurol Sci. 2020;429(Suppl):118113. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Barros A, Santos M, Sequeira J, et al. Effectiveness of cladribine in multiple sclerosis – clinical experience of two tertiary centers. Mult Scler. 2020;26(3 Suppl):278. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Eichau S, Dotor J, Lopez-Ruiz R. Cladribine in a real world setting. The real patients. Mult Scler. 2021;27(2 Suppl):713. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Horáková D, Vachová M, Tvaroh A, et al. Oral cladribine in the treatment of multiple sclerosis—data from the national registry ReMuS® registry. Cesk Slov Neurol N. 2021;86:555–561. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nicholas J, Mackie DS, Costantino H, et al. A cross-sectional survey evaluating cladribine tablets treatment patterns among patients with multiple sclerosis across the US enrolled in the MS lifelines patient support program. Neurology. 2022;98(18 Suppl):2868. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pfeuffer S, Rolfes L, Hackert J, et al. Effectiveness and safety of cladribine in MS: Real-world experience from two tertiary centres. Mult Scler. 2022;28:257–268. doi: 10.1177/13524585211012227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rosengren V, Ekström E, Forsberg L, et al. Clinical effectiveness and safety of cladribine tablets for patients treated at least 12 months in the Swedish post-market surveillance study “immunomodulation and multiple sclerosis epidemiology 10” (IMSE 10) Mult Scler. 2021;27(2 Suppl):623. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Thakre M, Inshasi J. Real world experience of oral immune reconstitution therapy (cladribine) in the treatment of multiple sclerosis in the United Arab Emirates. Mult Scler. 2020;26(3 Suppl):185. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Brownlee W, Haghikia A, Hayward B, et al. Comparative effectiveness of cladribine versus fingolimod in the treatment of highly active relapsing multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Rleat Disord. 2023;76:104791. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2023.104791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Butzkueven H, Spelman T, Hodgkinson S, et al. Real-world experience with cladribine in the MSBase registry. Mult Scler. 2021;27(2 Suppl):681. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Santos M, Sequeira J, Abreu P, et al. Safety and effectiveness of cladribine in multiple sclerosis: real-world clinical experience from 5 tertiary hospitals in Portugal. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2023;46:105–111. doi: 10.1097/WNF.0000000000000552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Giovannoni G, Boyko A, Correale J, et al. Long-term follow-up of patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis from the CLARITY/CLARITY Extension cohort of CLASSIC-MS: An ambispective study. Mult Scler. 2023;29:719–730. doi: 10.1177/13524585231161494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Patti F, Visconti A, Capacchione A, Roy S, Trojano M, CLARINET-MS Study Group Long-term effectiveness in patients previously treated with cladribine tablets: a real-world analysis of the Italian multiple sclerosis registry (CLARINET-MS) Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2020;13:1756286420922685. doi: 10.1177/1756286420922685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Allen-Philbey K, De Trane S, MacDougall A, et al. Disease activity 4.5 years after starting cladribine: experience in 264 patients with multiple sclerosis. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2023;16:17562864231200627. doi: 10.1177/17562864231200627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Magalashvili D, Mandel M, Dreyer-Alster S, et al. Cladribine treatment for highly active multiple sclerosis: real-world clinical outcomes for years 3 and 4. J Neuroimmunol. 2022;372:577966. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2022.577966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Signori A, Saccà F, Lanzillo R, et al. Cladribine vs other drugs in MS: Merging randomized trial with real-life data. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2020;7:e878. doi: 10.1212/NXI.0000000000000878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Meuth SG, Bayas A, Kallmann B, et al. Long-term management of multiple sclerosis patients treated with cladribine tablets beyond year 4. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2022;23:1503–1510. doi: 10.1080/14656566.2022.2106783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wiendl H, Schmierer K, Hodgkinson S, et al. Specific patterns of immune cell dynamics may explain the early onset and prolonged efficacy of cladribine tablets: a MAGNIFY-MS Substudy. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2022;10:e200048. doi: 10.1212/NXI.0000000000200048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ruschil C, Gabernet G, Kemmerer CL, et al. Cladribine treatment specifically affects peripheral blood memory B cell clones and clonal expansion in multiple sclerosis patients. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1133967. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1133967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Moser T, Schwenker K, Seiberl M, et al. Long-term peripheral immune cell profiling reveals further targets of oral cladribine in MS. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2020;7:2199–2212. doi: 10.1002/acn3.51206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Jacobs BM, Ammoscato F, Giovannoni G, Baker D, Schmierer K. Cladribine: mechanisms and mysteries in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2018;89:1266–1271. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2017-317411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Seiberl M, Feige J, Hilpold P, et al. Serum neurofilament light chain as biomarker for cladribine-treated multiple sclerosis patients in a real-world setting. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24:4067. doi: 10.3390/ijms24044067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Centonze D, Amato MP, Brescia Morra V, et al. Multiple sclerosis patients treated with cladribine tablets: expert opinion on practical management after year 4. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2023;16:17562864231183221. doi: 10.1177/17562864231183221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Habek M, Drulovic J, Brecl Jakob G, et al. Treatment with cladribine tablets beyond year 4: a position statement by southeast european multiple sclerosis centers. Neurol Ther. 2023;12:25–37. doi: 10.1007/s40120-022-00422-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Meca-Lallana V, García Domínguez JM, López Ruiz R, et al. Expert-agreed practical recommendations on the use of cladribine. Neurol Ther. 2022;11:1475–1488. doi: 10.1007/s40120-022-00394-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sørensen PS, Centonze D, Giovannoni G, et al. Expert opinion on the use of cladribine tablets in clinical practice. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2020;13:1756286420935019. doi: 10.1177/1756286420935019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Petrou P, Achiron A, Cohen EG, et al. Practical recommendations on treatment of multiple sclerosis with cladribine: an Israeli Experts Group Viewpoint. J Neurol. 2023;270:5188–5195. doi: 10.1007/s00415-023-11846-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Río J, Castilló J, Rovira A, et al. Measures in the first year of therapy predict the response to interferon beta in MS. Mult Scler. 2009;15:848–853. doi: 10.1177/1352458509104591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Tutuncu M, Altintas A, Dogan BV, et al. The use of Modified Rio score for determining treatment failure in patients with multiple sclerosis: retrospective descriptive case series study. Acta Neurol Belg. 2021;121:1693–1698. doi: 10.1007/s13760-020-01476-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Gasperini C, Prosperini L, Rovira À, et al. Scoring the 10-year risk of ambulatory disability in multiple sclerosis: the RoAD score. Eur J Neurol. 2021;28:2533–2542. doi: 10.1111/ene.14845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Sormani MP, Rio J, Tintorè M, et al. Scoring treatment response in patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2013;19:605–612. doi: 10.1177/1352458512460605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Sormani MP, Gasperini C, Romeo M, et al. Assessing response to interferon-β in a multicenter dataset of patients with MS. Neurology. 2016;87:134–140. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Sormani MP, Freedman MS, Aldridge J, Marhardt K, Kappos L, De Stefano N. MAGNIMS score predicts long-term clinical disease activity-free status and confirmed disability progression in patients treated with subcutaneous interferon beta-1a. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2021;49:102790. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2021.102790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kunchok A, Lechner-Scott J, Granella F, et al. Prediction of on-treatment disability worsening in RRMS with the MAGNIMS score. Mult Scler. 2021;27:695–705. doi: 10.1177/1352458520936823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Ruggieri S, Prosperini L, Al-Araji S, et al. Assessing treatment response to oral drugs for multiple sclerosis in real-world setting: a MAGNIMS Study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2024;95:142–150. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2023-331920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Keenan A, Gandhi K, Le H, et al. Prognostic value of the magnims score for assessment of disease modifying therapy in patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis treated with ponesimod. In: Abstract/Poster Presented at the 2022 Meeting of the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers, National Harbor, Maryland, USA, June 1–4 2022. Available at https://cmsc.confex.com/cmsc/2022/meetingapp.cgi/Paper/8094. Accessed 23 Feb 2024.

- 102.Jamroz-Wiśniewska A, Zajdel R, Słowik A, et al. Modified Rio score with platform therapy predicts treatment success with fingolimod and natalizumab in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis patients. J Clin Med. 2021;10:1830. doi: 10.3390/jcm10091830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Río J, Rovira À, Gasperini C, et al. Treatment response scoring systems to assess long-term prognosis in self-injectable DMTs relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis patients. J Neurol. 2022;269:452–459. doi: 10.1007/s00415-021-10823-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Hyun JW, Kim SH, Jeong IH, et al. Utility of the Rio score and modified Rio score in Korean patients with multiple sclerosis. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0129243. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0129243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.