This guideline addresses the appropriate use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in the primary care treatment of patients with joint pain believed to be caused by degenerative arthritis. It does not consider therapies other than drug treatment. General practitioners must use their professional knowledge and judgement when applying guideline recommendations to the management of individual patients. They should note the information, contraindications, interactions, and side effects contained in the British National Formulary.1

This is a summary of the full version of the guideline.2 In this article, the statements accompanied by categories of evidence (cited as Ia, Ib, IIa, IIb, III, and IV) and recommendations classified according to their strength (A, B, C, or D) are as described previously and are summarised in the box.3

Summary points

Nearly 1.5 million person years of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug treatment, at a cost of £150 million, were prescribed by general practitioners in 1995

Initial treatment for osteoarthritic pain should be paracetamol, followed by ibuprofen

Routine prophylaxis for gastrointestinal injury associated with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs is not appropriate in patients with osteoarthritis

Potential risks of side effects should be discussed with patients before starting or changing treatment

Paracetamol is the most cost effective drug, followed by ibuprofen

Topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents cannot be recommended as evidence based treatment

Methods

The methods used to develop the guideline have been described previously.3 Briefly, we searched the electronic databases Medline and Embase, using a combination of subject heading and free text terms aimed at locating systematic reviews, meta-analyses, randomised trials, quality of life studies, and economic studies. The search was backed up by the expert knowledge and experience of group members.

Strength of recommendation

A—Directly based on category I evidence

B—Directly based on category II evidence or extrapolated recommendation from category I evidence

C—Directly based on category III evidence or extrapolated recommendation from category I or II evidence

D—Directly based on category IV evidence or extrapolated recommendation from category I, II or III evidence

Categories of evidence

Ia—Evidence from meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials

Ib—Evidence from at least one randomised controlled trial

IIa—Evidence from at least one controlled study without randomisation

IIb—Evidence from at least one other type of quasiexperimental study

III—Evidence from non-experimental descriptive studies, such as comparative studies, correlation studies, and case-control studies

IV—Evidence from expert committee reports or opinions, clinical experience of respected authorities, or both

Synthesising and describing published reports

The quality of relevant studies retrieved was assessed, and the information from relevant papers was synthesised using meta-analysis. This provided valid estimates of treatment effects using approaches that provided results in a form that could best inform treatment recommendations.

Osteoarthritis

Caseload

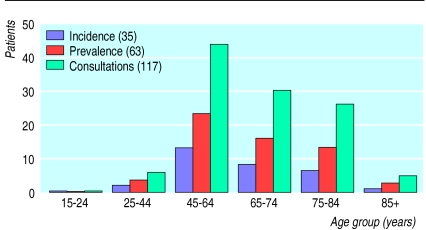

Osteoarthritis is one of a continuum of connective tissue disorders. The extent to which these interrelate and share common treatment is uncertain. Assuming a general practice list of 2000 patients, 374 will have a connective tissue disorder (ICD-9 codes 710-739). However, only 63 of the 374 will be formally identified as having osteoarthritis (fig 1).4

Figure 1.

Yearly caseload of osteoarthritis (ICD 715) in primary care (assuming a list size of 2000 patients)

Current patterns of drug use

In England, nearly 1.5 million person-years of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug treatment were prescribed by general practitioners in the year from April 1995. The cost was nearly £150 million, and ibuprofen and diclofenac constituted 26% and 37% respectively of the total volume. These figures do not include over the counter sales of ibuprofen.

Evidence from randomised trials

Pain at rest

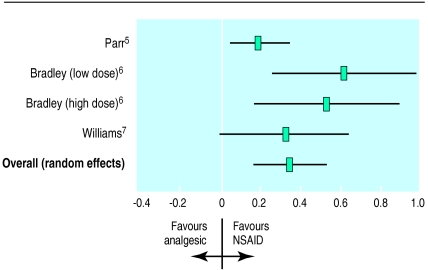

Three trials (four comparisons), in which a total of 969 patients were randomised to simple analgesia or a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug, examined pain at rest by using a visual analogue scale.5–7 The pooled standardised weighted mean difference was 0.35 (95% confidence interval 0.17 to 0.53), indicating that non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs were slightly more effective than simple analgesia (fig 2). We found evidence of heterogeneity (Q=6.69; df=3; P=0.08), confirming the appropriateness of the random effects model. However, a fixed effects approach provides a similar estimate of effect, with a standardised weighted mean difference of 0.29 (0.17 to 0.41). Thus, the pain score of the average patient treated with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs is less than that of 64% of patients in the control group.

Figure 2.

Resting pain score (standardised weighted mean difference) for non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID) compared with simple analgesia

Parr et al5 found a smaller effect than that estimated in either comparison by Bradley et al,6 and slightly smaller than that found by Williams et al.7 This may be because patients in the general practice population in the Parr study were less severely affected than those in other trials, who were recruited from secondary care, or it may reflect different inclusion criteria. Both the Bradley and Williams studies required a definite diagnosis of osteoarthritis, while the Parr study did not. In addition, the Parr study compared diclofenac sodium with co-proxamol, which may be more effective than paracetamol alone. However, the confidence intervals of all comparisons overlap, and we cannot exclude the play of chance.

Pain on motion

Two trials (three comparisons) provided estimates of pain on motion based on visual analogue scales. Although only one of the comparisons was statistically significant alone, the pooled standardised weighted mean difference based on all 390 patients randomised in this comparison is 0.28 (0.08 to 0.48; Q=1.27, df=2; P=0.53). The pain score of the average patient treated with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs is less than that of 61% of patients in the control group.

Time to walk 50 feet

Two trials (three comparisons) compared the effects of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and paracetamol treatment on the time taken to walk 50 feet. Overall, the estimate of effect for this outcome is 0.093 (−0.105 to 0.292), a very small effect that may be explained by chance. In addition, the practical importance of this benefit is uncertain: the mean difference in effect in favour of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs was less than one second in all comparisons.

Impact on quality of life

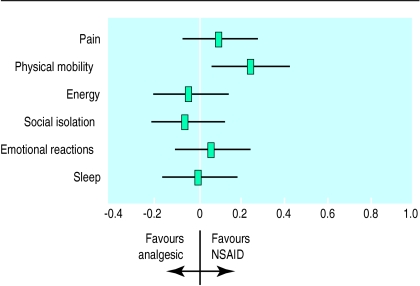

One study used the Nottingham health profile to describe different elements of the comparison between diclofenac and co-proxamol on broader health outcomes. The results showed no substantial differences in outcome for simple analgesia compared with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (fig 3).5

Figure 3.

Diclofenac sodium (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID)) compared with co-proxamol (analgesic) in relation to Nottingham health profile dimensions (standardised effect sizes)5

Treatment drop out

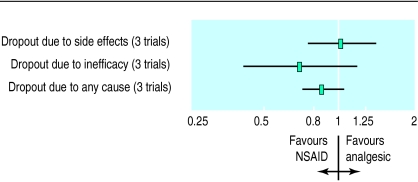

Stopping treatment was common in the three trials included in the meta-analyses of efficacy. Overall, there was a small and non-significant reduction in the risk of dropping out for patients allocated to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs rather than simple analgesia (relative risk 0.86, 0.72 to 1.03; Q=0.48, df=3; P=0.92) (fig 4). This translates to an overall reduction in the percentage of patients who drop out of 3.3% (−1.2 to 7.7) over an average of 4.5 months of treatment.

Figure 4.

Treatment withdrawal from included studies: relative risk

Efficacy of paracetamol based analgesia

Paracetamol and codeine combined seem to have a slightly greater analgesic effect than paracetamol alone.8 The combination of paracetamol and dextropropoxyphene also shows small and uncertain benefits over paracetamol alone.9 However, both combinations are associated with increased side effects (Ib).

Recommendations: treatment

Initial treatment for painful joints attributed to degenerative arthritis should be paracetamol in doses of up to 4 g daily (A)

If paracetamol fails to relieve symptoms, ibuprofen is the most appropriate alternative and should be substituted at a dose of 1.2 g daily (A)

If relief of symptoms is still inadequate, paracetamol may be added in doses of up to 4 g daily (D), or the dose of ibuprofen may be increased to 2.4 g daily (D), or both

If relief of symptoms is still inadequate, alternative drugs such as diclofenac or naproxen (A), or other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or co-codamol (D) may be considered

Safety

The relative risk of serious gastrointestinal complications with individual non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs was reviewed by Henry et al.10 They identified 12 controlled epidemiological studies examining 14 drugs from which safety relative to ibuprofen could be derived. The data supported the conclusion of the Committee on Safety in Medicines that ibuprofen is the lowest risk non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug and azapropazone the highest risk agent. The review also presented evidence that the risk of gastrointestinal injury from non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs is greater at higher doses. The magnitude of this increased risk is difficult to estimate since different studies used different definitions of high dose. However, high dose ibuprofen (2.4 mg daily) may be no safer than those non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs defined by the Committee on Safety in Medicines as being of intermediate risk—drugs such as diclofenac and naproxen.

Preventing gastrointestinal injury

Statement: H2 blockers, misoprostol and proton pump inhibitors reduce the risk of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced duodenal ulcers (I) Statement: misoprostol and proton pump inhibitors also reduce the risk of other serious upper gastrointestinal injury (II)

Both H2 antagonists and misoprostol reduced the risk of duodenal ulcers when given long term but not short term.11 Omeprazole seems as effective as misoprostol in healing and preventing ulcers induced by non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and it seems to be better tolerated.12

In a recent large double blind trial, primary and secondary care patients with rheumatoid arthritis who were taking non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs were randomised to treatment with misoprostol or placebo.13 The trial assessed the development of serious upper gastrointestinal complications detected by clinical symptoms or findings (rather than scheduled endoscopy) and found a small reduction, of borderline significance, in favour of misoprostol. Twenty five of 4404 patients taking misoprostol and 42 of 4439 patients receiving placebo had a serious upper gastrointestinal complication. The odds ratio for serious gastrointestinal complication was 0.60 (95% confidence interval 0.35 to 1.00 by Gart exact method) in those taking misoprostol over 6 months of follow up. The number needed to treat to prevent one serious gastrointestinal complication in this period is 264 (132 to 5703). In the first month of the study, 5% more patients taking misoprostol withdrew, primarily because of diarrhoea and other side effects.

On the basis of this trial in patients with rheumatoid arthritis,13 a general policy of prescribing prophylaxis of gastrointestinal injury associated with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for osteoarthritis patients (generally a less severe patient group) does not seem appropriate. This may not be true for a selected group of high risk patients (for example, those with previous gastrointestinal bleeding) in whom non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug treatment cannot be modified. However, the method of reporting and small number of serious gastrointestinal events in the large trial of misoprostol prophylaxis13 preclude examination of benefits of treatment in subgroups.

Reducing gastrointestinal symptoms

Statement: H2 antagonists may have a small impact upon severe gastric symptoms in patients taking non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, though it is not clear that benefits generally exceed those from antacids (I)

There are few available data examining strategies to reduce gastrointestinal symptoms induced by non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. In one randomised trial of patients with osteoarthritis treated with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, allocation to nizatidine reduced appreciably the use of (much less expensive) antacids, but overall symptoms were similar in the two groups.14 Similarly, in a randomised trial of patients with either rheumatoid arthritis or osteoarthritis, allocation to ranitidine led to no difference in epigastric pain or in withdrawal from treatment.15 In a randomised trial of patients with ulcers induced by non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, patients allocated to omeprazole had less abdominal pain than those allocated to misprostol.16

Recommendations: safety

Potential risks of side effects of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs should be discussed with patients before starting or changing treatment (D)

Patients’ requirements for non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs should be reviewed regularly (at least six monthly) and the use of these drugs on a limited “as required” basis should be encouraged. At review doctors should consider substituting paracetamol for a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (D)

If upper gastrointestinal side effects occur with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, consider the following review steps:Establish the accuracy of the diagnosis of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug associated dyspepsia (D)Review and confirm the need for any drug treatment (D)Consider substituting paracetamol for a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (D)If paracetamol provides insufficient analgesic relief, consider substituting co-codamol (D)Consider substituting low dose ibuprofen (1.2 g daily) for co-codamol (D)Consider lowering the dose of the currently used non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (B)

If sufficient analgesia is achieved only with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and the patient has dyspeptic symptoms, consider using acid suppression as adjunctive therapy (D)

The guideline development group could not find sufficient evidence to decide whether these patients required endoscopy (D)

Economic considerations

Statement: substantial differences are found in the costs of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, both between drugs and between different preparations (II) Statement: there is no evidence to support the use of more expensive preparations over cheaper ones (II) Statement: no evidence supporting the use of the modified release preparations has been found (IV)

Paracetamol remains a cost effective alternative to any non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug. It is cheaper and has less gastrointestinal toxicity, and similar proportions of patients withdraw from treatment.

Ibuprofen seems safer than diclofenac or naproxen10 and is three to four times cheaper, given the forms in which these drugs are currently prescribed. Ibuprofen is therefore the most cost effective first line non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

The purchase costs of different preparations of the same non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug vary widely. There is no evidence to support the use of more expensive preparations over cheaper ones or the use of the modified release preparations. Head to head trials comparing different non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are of a poor quality and show many biases.17,18

Routine and prophylactic treatment with misoprostol for unselected patients taking non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs has not been shown to be cost effective. Case review and sequential selection of treatment, beginning with simple analgesia, will probably minimise the frequency of adverse events in the general patient group.

Preventive strategies should not be confused with treatment of (common) dyspepsia, where prescription or over the counter purchase of antacids may be considered when non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug treatment cannot be modified.

Recommendations: cost effectiveness

Patients with joint pain believed to be caused by degenerative arthritis should be given paracetamol initially, and if this is inadequate ibuprofen is the most cost effective alternative (C)

Modified release preparations are relatively expensive, and as there is no evidence that they are more effective than standard treatment, they should not be used (D)

Prophylaxis with misoprostol or proton pump inhibitors should not be used routinely as it is not cost effective in reducing serious gastric events (D)

In some patients at higher risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding or perforation, prophylaxis may be cost effective, but further evidence of this is required (D)

Topical preparations

Statement: the appropriate role of topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs is unclear (IV)

Topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs may have some benefit in patients with osteoarthritis as their use may reduce the risk of unwanted gastrointestinal side effects. Well designed, large scale randomised trials in which topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory treatment is compared directly with oral non-steroidal anti-inflammatory treatment in patients with osteoarthritis are required to estimate the relative effectiveness and efficiency of these alternative treatments. We were unable to find any such trial. Therefore, the use of topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in patients with osteoarthritis cannot be recommended as an evidence based treatment.

Research questions

In developing this guideline the group identified important issues that need further research. Well designed, large scale randomised trials that compare alternative treatments directly are required to evaluate the following:

Recommendation: use of topical preparations

Topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents cannot be recommended as an evidence based treatment (D)

(1) What is the efficacy and safety of simple and compound analgesics compared with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs?

(2) What are the consequences of advising patients to take non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or paracetamol “as required” compared with continuously?

(3) What is the appropriate role of modified release non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug preparations?

(4) What is the best treatment for patients taking non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs who present with dyspeptic symptoms?

(5) Is prophylaxis with misoprostol or proton pump inhibitor agents cost effective in high risk patients in whom withdrawal of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug therapy is not possible?

(6) What is the relative effectiveness and efficiency of topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and oral non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in patient with osteoarthritis?

(7) What is the role of the new cyclo-oxygenase-2 selective non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and nitrosated compounds in the primary care treatment of patients with osteoarthritis?

(8) In patients taking non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, what are the added risks of gastrointestinal injury when they also have Helicobacter pylori infection?

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Philip Helliwell, Professor David Henry, Dr Martin Lawrence, and Professor Malcolm Man-Son-Hing for reviewing the full version of the draft guideline. We thank Janette Boynton, Julie Glanville, Susan Mottram, and Anne Burton for their contribution to the functioning of the guidelines development group and the development of the practice guideline.

Appendix

The guideline development group comprises the following members in addition to the authors: Professor Howard Bird, Chapel Allerton Hospital, Leeds; Mr Mark Campbell, prescribing manager, Regional Drug and Therapeutics Centre, Newcastle upon Tyne; Dr John Dickson, general practitioner, Northallerton; Dr David Graham, general practitioner, Hexham; Professor Christopher Hawkey, University Hospital, Nottingham; Dr Keith MacDermott, general practitioner, York; Dr Tony McKenna, general practitioner, Cleveland; Dr Maureen Norrie, general practitioner, Stockton on Tees; Dr Colin Pollock, medical director, Wakefield Health Authority; Dr Jeff Rudman, Workington.

The project steering group comprised: Professor Michael Drummond, Centre for Health Economics, University of York; Professor Andrew Haines, Department of Primary Care and Population Studies, University College London Medical School and Royal Free Hospital School of Medicine; Professor Ian Russell, Department of Health Sciences and Clinical Evaluation, University of York; Professor Tom Walley, Department of Pharmacology and Therapeutics, University of Liverpool.

Footnotes

Funding: The work was funded by the Prescribing Research Initiative of the Department of Health.

Conflict of interest: None.

References

- 1.British national formulary. London: British Medical Association, Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain; 1996. (No 32.) [Google Scholar]

- 2.North of England Evidence Based Guidelines Development Group. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) versus basic analgesia in the treatment of pain believed to be due to degenerative arthritis. Newcastle: Centre for Health Services Research; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eccles M, Freemantle N, Mason JM. North of England Evidence Based Guidelines Development Project: methods of developing guidelines for efficient drug use in primary care. BMJ. 1998;316:1232–1235. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7139.1232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McCormick A, Fleming D, Charlton J. Morbidity statistics in general practice: fourth national study 1991-1992. London: HMSO; 1995. (Series MB5 No 3.) [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parr G, Darekar B, Fletcher A, Bulpitt CJ. Joint pain and quality of life; results of a randomized trial. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1989;27:235–242. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1989.tb05356.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bradley JD, Brandt KD, Katz BP, Kalasinski LA, Ryan SI. Treatment of knee osteoarthritis: relationship of clinical features of joint inflammation to the response to a nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug or pure analgesic. J Rheumatol. 1992;19:1950–1954. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Williams HJ, Ward JR, Egger MJ, Neuner R, Brooks RH, Clegg DO, et al. Comparison of naproxen and acetaminophen in a two-year study of treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee. Arthritis Rheum. 1993;36:1196–1206. doi: 10.1002/art.1780360904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Craen AJM, Guilio GD, Lampe-Schoenmaeckers AJEM, Kessels AGH, Kleijnen J. Analgesic efficacy and safety of paracetamol-codeine combinations versus paracetamol alone: a systematic review. BMJ. 1996;313:321–325. doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7053.321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wan Po LA, Zhang WY. Systematic overview of co-proxamol to assess analgesic effects of addition of dextroproxyphene to paracetamol. BMJ. 1998;315:1565–1571. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7122.1565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Henry D, Lim LL-Y, Garcia Rodriguez LA, Perez Gutthann S, Carson JL, Griffin M, et al. Variability in risk of gastrointestinal complications with individual non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: results of a collaborative meta-analysis. BMJ. 1996;312:1563–1566. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7046.1563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koch M, Dezi A, Ferrario F, Capurso L. Prevention of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced gastrointestinal mucosal injury: a meta analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:2321–2332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hawkey CJ, Swannell AJ, Yeomans ND, Langstrom G, Lofberg, Taure E. Site specific ulcer relapse in non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug users: improved prognosis with H pylori and with omeprazole compared to misoprostol. Gut. 1996;39(suppl 1):W5. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Silverstein FE, Graham DY, Senior JR, Davies HW, Struthers BJ, Bittman RM, et al. Misoprostol reduces serious gastrointestinal complications in patients with rheumatoid arthritis receiving nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 1995;123:241–249. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-123-4-199508150-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levine LR, Cloud ML, Enas NH. Nizatidine prevents peptic ulceration in high risk patients taking nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Arch Intern Med. 1993;153:2249–2254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ehsanullah RSB, Page MC, Tildesley G, Wood RJ. Prevention of gastroduodenal damage induced by non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: controlled trial of ranitidine. BMJ. 1988;297:1017–1021. doi: 10.1136/bmj.297.6655.1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hawkey CJ, Swannell AJ, Eriksson S, Walan A, Lofberg I, Taure E, et al. Benefits of omeprazole over misoprostol in healing NSAID-associated ulcers. Gut. 1996;38(suppl 1):T155. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gøtzsche PC. Methodology and overt and hidden bias in reports of 196 double-blind trials of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs in rheumatoid arthritis. Controlled Clin Trials. 1989;10:31–56. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(89)90017-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rochon PA, Gurwitz JH, Simms RW, Fortin PR, Felson DT, Minaker KL, et al. A study of manufacturer-supported trials of nonsteriodal anti-inflammatory drugs in the treatment of arthritis. Arch Intern Med. 1994;154:157–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]