Abstract

Halocin S8 is a hydrophobic microhalocin of 36 amino acids (3,580 Da) and is the first microhalocin to be described. This peptide antibiotic is unique since it is processed from inside a much larger, 33,962-Da pro-protein. Halocin S8 is quite robust, as it can be desalted, boiled, subjected to organic solvents, and stored at 4°C for extended periods without losing activity. The complete amino acid sequence of halocin S8 was obtained first by Edman degradation of the purified protein and verified from the halS8 gene: H2N-S-D-C-N-I-N-S-N-T-A-A-D-V-I-L-C-F-N-Q-V-G-S-C-A-L-C-S-P-T-L-V-G-G-P-V-P-COOH. The halS8 gene is encoded on an ∼200-kbp megaplasmid and contains a 933-bp open reading frame, of which 108 bp are occupied by halocin S8. Both the halS8 promoter and the “leaderless” halS8 transcript are typically haloarchaeal. Northern blot analysis revealed three halS8 transcripts: two abundant and one minor. Inspection of the 3′ end of the gene showed only a single, weak termination site (5′-TTTAT-3′), suggesting that some processing of the larger transcripts may be involved. Expression of the halS8 gene is growth stage dependent: basal halS8 transcript levels are present in low concentrations during exponential growth but increase ninefold during the transition to stationary phase. Initially, halocin activity parallels halS8 transcript levels very closely. However, when halocin activity plateaus, transcripts remain abundant, suggesting inhibition of translation at this point. Once the culture enters stationary phase, transcripts rapidly return to basal levels.

Halocins are protein antibiotics that are produced by extremely halophilic members of the domain Archaea and are externalized into the environment, where they kill or inhibit other haloarchaeons. As such, halocins are the haloarchaeal equivalent of the well-characterized protein antibiotics called bacteriocins that are produced by some 30 genera of the domain Bacteria (2). The term “halocin” was coined in 1982 by Francisco Rodriguez-Valera, who assumed that these substances were bacteriocins and who logically applied a similar nomenclature (28). Although archaeons share a “prokaryotic” cellular organization and morphological motif with members of the domain Bacteria, they are in separate domains and are only distantly related (41). Consequently, halocins and other protein antibiotics produced by Archaea (e.g., sulfolobicins) are more aptly classified as “archaeocins” than as “bacteriocins.”

In contrast to the numerous examples of antibiotic producers in the domains Bacteria and Eucarya, antibiotic production in the domain Archaea has been limited essentially to the protein antibiotics produced by the haloarchaea and one nonhalophilic example from the crenarchaeal genus Sulfolobus (25). Nonetheless, halocin production has been shown to be a near-universal feature of haloarchaeal rods (40) and, based on antagonism studies, hundreds of different types have been found to exist (17, 40). Despite their abundance, only a handful of halocins have been characterized at the protein level (halocins H4, H6, and R1 [16, 26, 34, 39; A. M. Perez and R. F. Shand, SACNAS 1999 Natl. Conf. Prog., abstr. 34, p. 137, 1999), and only one halocin (H4) has been characterized at both the gene and mRNA transcript levels (6). The mechanism of action has been established only for halocin H6 (a Na+/H+ antiporter inhibitor [18]), and the mechanism behind halocin immunity has not been established for any halocin-producing strain.

The archaeal basal transcription apparatus is a simplified version of the eucaryal apparatus and is comprised only of the TATA box, TATA box binding protein (TBP) homologs, transcription factor IIB (TFB) homologs, and a single PolII-like RNA polymerase (38; J. R. Palmer, D. K. Thompson, W. C. Ray, and C. J. Daniels, Abstr. 97th Gen. Meet. Am. Soc. Microbiol. 1997, abstr. I-52, p. 330, 1997). The haloarchaea are unusual in that they possess multiple copies of both the TBP genes and the TFB genes (Palmer et al., Abstr. 97th Gen. Meet. Am. Soc. Microbiol.). Elucidating the combination of factors involved in both gene regulation in general, and stationary-phase gene regulation specifically, has become an important focus in haloarchaeal research. To do this, model regulatory systems are needed. The halocin H4 gene (6), and now the halocin S8 gene, are useful models for studying stationary-phase gene expression in the haloarchaea, since they are expressed initially at the transition to stationary phase (34).

In order to explore halocin diversity at both the protein and gene expression levels and to exploit halocins as models for stationary-phase gene regulation, many more halocins need to be characterized. Halocin S8 from an uncharacterized haloarchaeon (strain S8a) isolated from the Great Salt Lake, Utah, by Penny Amy from the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, is the focus of this work. We describe here the characterization of halocin S8 from protein purification to gene expression. In bacteriocin nomenclature, bacteriocins of less than 5 to 10 kDa are placed in a special category called “microcins” (20). In parallel with this terminology, halocin S8 (3,580 Da) has been designated a “microhalocin.”

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Haloarchaeal strains, media, and growth conditions.

The haloarchaeal strain S8a was grown aerobically at 41°C in a complex medium (pH 7.0) containing 4.28 M NaCl, 81 mM MgSO4, 10.2 mM Na3C6H5O7, 26.8 mM KCl, 1.36 mM CaCl2, 41.7 mM MOPS (3-[N-morpholino]propanesulfonic acid), trace elements [50 ng of CuSO4 · 5H2O, 4.55 μg of Fe(NH4)2(SO4)2 · 6H2O, 300 ng of MnSO4 · H2O, and 440 ng of ZnSO4 · 7H2O per ml], 1% (wt/vol) peptone (Oxoid), and MAZU DF 204 antifoam (1:10,000 [vol/vol]; PPG Industries, Inc., Gurnee, Ill.). Small-scale growth physiology studies were performed in 25-ml cultures grown in 125-ml baffled flasks (Kimble Glass, Vineland, N.J.) aerated in a model G76 orbital shaking water bath (New Brunswick Scientific Co., Inc., Edison, N.J.) at ∼200 rpm. For protein purification, three 2-liter cultures were grown in 4-liter baffled flasks (Bellco Glass, Inc., Vineland, N.J.), aerated in a model G-25 controlled environment incubator shaker (New Brunswick) at 125 rpm until the growth rate began to slow, and then the rpm was increased to 175 until the cells reached stationary phase.

Growth of the indicator organism used for detecting halocin activity (Halobacterium salinarum NRC817) and the activity assays themselves were as described previously (6) using 1.5% (wt/vol) bottom-agar and 0.75% wt/vol top-agar lawns in the assay. In all cases, growth was monitored spectrophotometrically using a Shimadzu UV160U dual-beam spectrophotometer at 600 nm (Shimadzu Scientific Instruments, Inc., Columbia, Md.).

Antagonism studies.

Culture supernatants (10 μl) from strain S8a that contained halocin S8 (HalS8) activity were spotted onto top-agar lawns of the following haloarchaea: H. salinarum NRC817 and Halobacterium sp. strains GN101, TuA4, and GRB; Haloferax mediterranei R4 (ATCC 33500), Haloferax gibbonsii, and Haloferax volcanii; Natronococcus occultus; and Natronobacter pharaonis, Natronobacter gregoryi, and Natronobacter magadii. Uninoculated media (10 μl) used to grow each culture were also spotted onto plates as a control. The plates were incubated and inspected for the presence of zones of inhibition in the indicator lawn.

Desalting.

Culture supernatants were desalted with 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.0) to 10 mM NaCl by four recursive concentrations with a 5-kDa nominal molecular weight cutoff (NMWCO) tangential-flow spin filter. After each concentration, the material was resuspended in 10 to 12 volumes of 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.0) and then reconcentrated. The desalted solution was then assayed using a lawn of H. salinarum NRC817. However, since the assay necessarily involves placing the desalted halocin back onto medium containing 4 M NaCl, it is unknown whether desalting actually denatures the halocin and then the halocin just refolds once placed back into a hypersaline environment or whether the halocin remains folded and active when desalted.

TFF.

Three 2-liter S8a cultures were pooled at early stationary phase (optical density at 600 nm [OD600] of ∼0.9), and the cells were removed using a tangential flow filtration (TFF) system equipped with a 0.45-μm (pore-size) Pellicon filter (Millipore, Bedford, Mass.). The cell filtrate was then processed through NMWCO filters of sequentially smaller pore sizes: 100, 30, and 10 kDa. Each filtrate and retentate was assayed so that the activity on either side of the filter could be determined. Approximately 50% of the total activity from the initial eight liters was retained by the 30-kDa filter in a volume of 250 ml, which represented a concentration of 24-fold (∼108 arbitrary units [AU] of total activity). This material was then concentrated another 46-fold using Amicon 3-kDa Centriprep 3 concentrators (Millipore) in preparation for gel filtration chromatography.

Gel filtration column chromatography.

Initial HalS8 purification was performed on a Bio-Gel P30M polyacrylamide matrix (2.5- to 40-kDa NMW range; Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.), with bed dimensions of 2.5 by 110 cm, and hydrated with S8 basal salts running buffer (S8 medium lacking the peptone, trace elements, MOPS, and defoamer). Concentrated 30-kDa TFF retentate (5 ml at 4.5 mg/ml; ∼4.1 × 106 AU of halocin activity) was loaded onto the column. The column was run at 0.02 ml/min, and 0.5-ml fractions were collected. Fractions containing various levels of halocin activity were subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) as described below.

Reversed-phase HPLC.

Reversed-phase high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) was performed on a BioCAD Sprint HPLC (PE Biosystems, Inc., Framingham, Mass.) equipped with a Poros 10 R2/H (4.6-by-100-mm) reversed-phase column. Gel filtration fractions that contained activity were pooled and then simultaneously concentrated and desalted with 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.0) using Amicon 3-kDa NMWCO Centiprep 3 concentrators. The concentrated, desalted HalS8 was loaded onto the column, and the column was washed isocratically with a 0.1% (vol/vol) trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) aqueous phase (65%)–acetonitrile (ACN) organic phase (35%) for 10 column volumes at 5 ml/min, followed by a TFA-ACN gradient of 65 to 35% to 20 to 80% for 15 column volumes at the same rate. Column fractions (2 ml) were assayed for activity using 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.0) as the diluent for the twofold serial dilutions. Note that in the absence of halocin, ACN concentrations of 75 to 100% produce small zones of inhibition with very discrete edges on the lawn cells. These zones are easily distinguished from zones resulting from halocin activity. In addition, ACN has a synergistic effect on halocin activity, with activity increasing by as much as 16-fold when ACN is included in the diluent. HPLC fractions containing activity were lyophilized in an AES 1010 SpeedVac (Savant, Bethesda, Md.), resuspended in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.0), and subjected to SDS-PAGE as described below.

SDS-PAGE.

Tricine polyacrylamide gradient gels consisting of a 16.5% T, 6% C, and 13% glycerol separating (resolving) gel, a 10% T and 3% C spacer gel, and a 4% T and 3% C stacking gel (32) were used to analyze column fractions. These gels are insensitive to NaCl concentrations as high as 2.2 M and allow samples containing high levels of salt (e.g., samples from gel filtration) to be electrophoresed next to samples containing no salt (e.g., samples from reversed-phase HPLC) without distortion (see Fig. 1A). Samples from gel filtration fractions containing 4.3 M NaCl were mixed 1:1 with Serva Blue G running dye (32), reducing the NaCl concentration to 2.15 M. Proteins were silver stained according to the method of Morrissey (21) as modified by Miercke et al. (19).

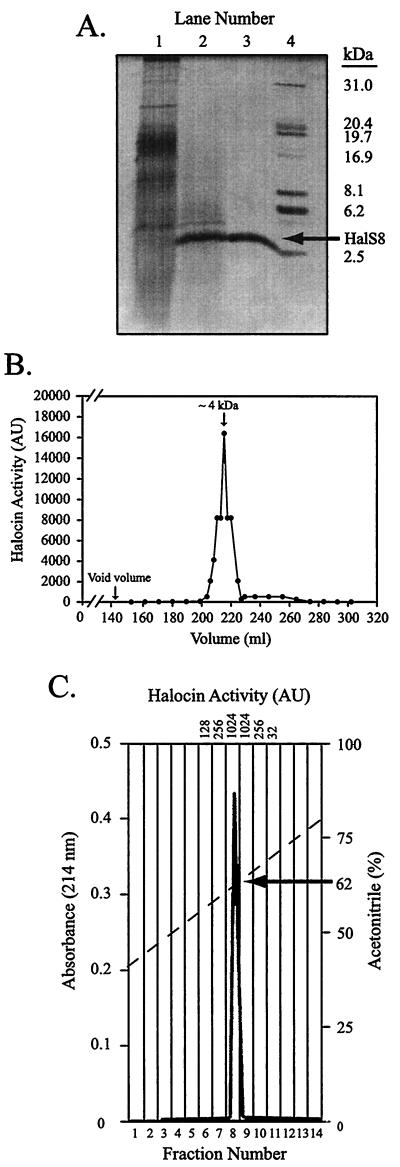

FIG. 1.

Purification of halocin S8. (A) SDS-PAGE (silver stained) analysis of material from each of the three purification steps. Lane 1, concentrated 30-kDa retentate from TFF of culture supernatant; lane 2, a P30M gel filtration column fraction containing HalS8 activity; lane 3, reversed-phase HPLC fraction containing HalS8 activity; lane 4, protein size standards (in kilodaltons). (B) Elution profile of HalS8 from a P30M gel filtration column loaded with concentrated 30-kDa retentate from TFF. Halocin S8 eluted at about 4 kDa. (C) Reversed-phase HPLC profile of pooled, concentrated, and desalted gel filtration column fractions containing HalS8 activity (AU are indicated at the top). The ACN gradient is shown as a dashed line, with HalS8 eluting at 62% ACN. Panel A is reprinted with permission from A. Oren (ed.), Microbiology and Biogeochemistry of Hypersaline Environments (1999), p. 303 (CRC Press, Boca Raton, Fla.).

Oligodeoxynucleotide probe design.

One stretch of seven amino acids (NTAADVI) and one stretch of six amino acids (CFNQVG) from the HalS8 sequence with relatively low degeneracy (see Fig. 2) were used to design two degenerate oligodeoxynucleotide probes: S8OLI1 and S8OLI3. S8OLI1 (5′-AAYACIGCIGCIGAYGTIAT-3′; I = DEOXYINOSINE, N = ACTG, Y = CT, R = AG) was a fourfold degenerate 20-mer containing deoxyinosines in all positions where there was potential for more than two different nucleotides; S8OLI3 (5′-TGYTTYAAYCARGTNGG-3′) was a 64-fold degenerate 17-mer. These probes were used independently to screen S8 genomic digests on Southern blots for restriction fragments containing the gene coding for HalS8.

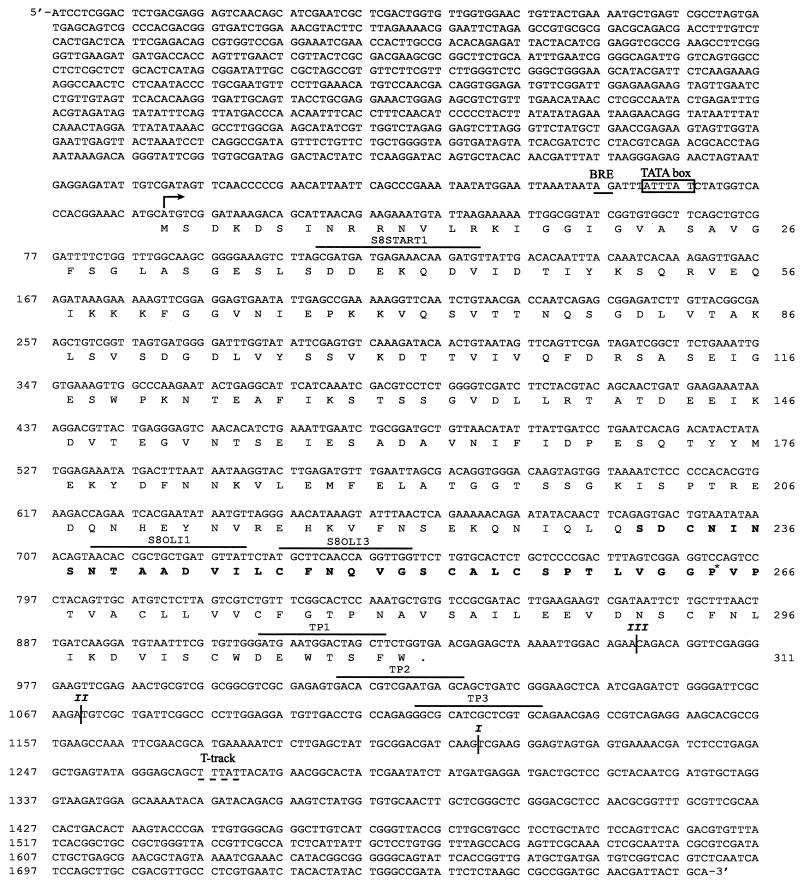

FIG. 2.

DNA sequence of the 2,873-bp PstI/EcoRV fragment containing the halS8 gene. Locations of probes S8OLI1 and S8OLI3 used to detect the halS8 gene on Southern blots, probes TP1, TP2, and TP3 used to detect the ends of various transcripts on Northern blots, and the primer S8START1 for determining the start site of transcription are shown with lines above the DNA sequence. The start site of transcription (arrow), the putative haloarchaeal promoter (rectangle), the transcription factor B recognition element (BRE; underlined), and a haloarchaeal termination T-tract (dashed underline) are indicated. Approximate locations of the 3′ ends of transcripts I, II, and III determined by Northern analysis are indicated by |. The amino acid sequence of the 933-bp open reading frame encoding the 311-amino-acid pro-protein is indicated below the DNA sequence, with the 36-amino-acid HalS8 internal peptide in boldface. The 230 amino acids upstream of the HalS8 peptide and the 45 amino acids downstream of it are indicated in regular face. The single amino acid in the HalS8 peptide that differed in the sequence determined from the DNA sequence (proline) and the sequence determined by Edman degradation (glycine) is indicated by an asterisk.

Southern blotting, cloning, and sequencing.

Routine molecular techniques were used to clone the halS8 gene (1, 31). Briefly, Southern blotting showed that an ∼3-kb PstI/EcoRV restriction fragment hybridized with the S8OLI1 and S8OLI3 probes. Fragments of the appropriate size were excised from an agarose gel and purified using the QIAEX II Gel Extraction System (Qiagen, Valencia, Calif.). Restriction fragments were ligated into the pBC SK+ phagemid vector (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) and then transformed into supercompetent Epicurian coli strain XL1-Blue MRF′ cells (Stratagene). Transformants were screened by Southern hybridization with 32P-labeled S8OLI3 to identify the plasmids that carried the fragment of interest, and the fragments were sequenced.

Northern hybridization.

Northern hybridization was performed as previously described (33), except that 3 μg of total RNA was run on a 1-mm-thick vertical gel, and RNA was transferred using the alkaline transfer technique as described by Bio-Rad Laboratories, substituting 20× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate) for 0.4 N NaOH.

A halS8-specific probe was amplified by PCR using the primers S8JUSTF1 (5′-TATAAACAGTAACACCGCTGC-3′) and S8JUSTR1 (5′-GGGACTGGACCTCCGAC-3′) (these primers amplified only the region coding for the mature protein; see Fig. 2) and then 32P labeled via random priming (Life Technologies, Inc., Grand Island, N.Y.). An ∼110-bp portion of the S8a 7S gene was amplified using the primers S87SF2 (5′-CCAACGTGGAAGCCTCGTC-3′) and S87SR2 (5′-GGTGGTCCGCTGCTCACTTC-3′) and then 32P labeled via random priming (Life Technologies). These 32P-labeled probes were denatured at 94°C for 10 min and then added to the hybridization buffer and allowed to hybridize overnight at 65°C.

Three 17-base oligodeoxynucleotides (TP1, 5′-AAGCTAGTCCATTCATC-3′; TP2, 5′-TGCTCATTCGACGTGTC-3′; TP3, 5′-TGCACGAGCGATGCGCC-3′; see Fig. 2) complementary to the 3′ end of halS8 transcript (with TP1 ending six bases before the translational stop codon and TP2 and TP3 ending 94 and 194 bases downstream of the stop codon, respectively) were end labeled with 32P and used to probe three Northern blots of total S8a RNA. The lengths of the three halS8 transcripts were measured, and the approximate endpoints were determined.

Fluorescent primer extension.

Inspection of the DNA sequence of the 2,873-bp PstI/EcoRV fragment revealed a putative haloarchaeal TATA box upstream of the amino-terminal methionine of the halS8 ORF. A primer complementary to the derived transcript ∼100 bp downstream of the putative TATA box was designed using Oligo software (Molecular Biology Insights, Inc., Cascade, Colo.). The primer (5′-ACATCTTGTTTCTCATCATCGC-3′) was synthesized with or without a 6-FAM (6-carboxy-oxyfluorescein) label at the 5′ end. The 6-FAM-labeled primer was used in a primer extension reaction containing 5 μl of a 2-mg/ml mixture of total S8a RNA (time point 5; see Fig. 3), 2 μl of 50 mM labeled primer, and 5 μl of water. The mixture was incubated at 70°C for 10 min and then placed on ice. Once cooled, 4 μl of 5× first-strand buffer, 2 μl of 0.1 M dithiothreitol, and 2 μl of 5 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates were added and then the mixtures were incubated at 50°C for 1 h. The unlabeled primer was annealed to the PstI/EcoRV fragment, and a fluorescent sequencing reaction was performed using the PRISM Ready Reaction BigDye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Kit. The products from the two reactions were run side by side on a 48-cm, 4.75%, 6 M urea, 1× TBE Long Ranger polyacrylamide gel (FMC Bioproducts, Rockland, Maine) using an ABI 377 fluorescent sequencer (Perkin-Elmer/Applied Biosystems, Inc., Foster City, Calif.). The position of the primer extension product relative to the bands in the adjacent sequencing lane was used to identify the start site of transcription.

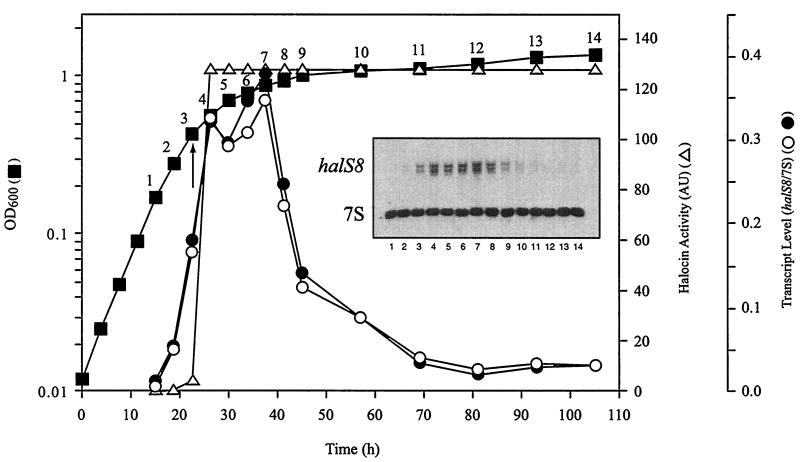

FIG. 3.

Correlation of HalS8 activity and halS8 transcript levels with the growth phase of strain S8a. Growth of strain S8a (■; g = 3.75 h) was determined by monitoring the OD600. The numbers (1 to 14) above the growth curve indicate where halocin and RNA samples were taken during the experiment. Halocin activity (▵) is reported in AU, with the initial detection of activity in the culture supernatant indicated by an arrow. Total transcript levels (● and ○) for the two most abundant halS8 mRNAs are plotted as the ratio of the halS8 transcripts (inset) divided by the level of 7S RNA (a transcript produced by an unrelated constitutively expressed gene that serves as an internal control for the amount of total RNA loaded for each sample; inset) as quantified by using a PhosphorImager. The inset is a Northern blot showing the relative abundance of each transcript from each of the 14 samples.

CHEF electrophoresis.

Contour-clamped homogeneous electric field (CHEF) gel analysis was performed as described previously (6), except that pulse times were varied between 50 and 80 s for 20 h.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence of the halS8 gene and the corresponding amino acid sequence shown in Fig. 2 have been assigned GenBank accession no. AF276080.

RESULTS

Activity spectrum of halocin S8.

The activity spectrum of HalS8 appears to be fairly narrow since HalS8-laden supernatants inhibited the growth of only H. salinarum NRC817, Halobacterium sp. strain GRB, and H. gibbonsii. All other haloarchaeal strains tested were insensitive.

Halocin S8 protein.

Strain S8a culture supernatants containing halocin activity were subjected to three preliminary treatments prior to developing a purification scheme. First, the supernatant was desalted with 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.2) using tangential-flow spin filters with a 5-kDa NMWCO. The ability to withstand desalting without significant loss of activity allows the use of protein purification methods, such as ion exchange, which are not routinely available when purifying halophilic proteins that require high levels of salt to remain stable and active. The desalted HalS8 supernatant had the same activity as the culture supernatant, and the desalted halocin could be stored for months at 4°C without losing activity. Second, the desalted supernatant was treated with proteases to demonstrate that the inhibitory activity is protein based and not due to the presence of a small, toxic metabolite or other nonproteinaceous substance. Activity in desalted, HalS8-containing supernatants was eliminated using proteinase K but was refractory to treatment with trypsin. Third, supernatants were heated at various temperatures and sampled periodically for halocin activity in order to assess heat stability. For halocins that are heat stable, this treatment can result in the precipitation of a significant amount of contaminating protein. Supernatants containing HalS8 showed no loss of activity after heating at 94°C (i.e., boiling at 2,113 m) for 1 h.

Batch culture growth experiments (50 ml) with strain S8a showed that maximum halocin activity occurred in stationary phase and then persisted at these levels for >80 h (see Fig. 3). Consequently, a stationary-phase S8a culture (6 liters) was used to purify HalS8 in three steps: (i) TFF using filters with progressively smaller NMWCOs, (ii) size exclusion gel filtration chromatography, and (iii) reversed-phase HPLC (see Materials and Methods). Figure 1A shows the SDS-PAGE protein profile from each step of the purification. In step 1, HalS8 activity was partitioned about equally between the 30-kDa retentate and the 30-kDa filtrate. There were many contaminating proteins that were in the 8- to 20-kDa size range (Fig. 1A, lane 1). Halocin S8 was separated from most of the contaminants in the 30-kDa retentate using a P30M gel filtration size exclusion matrix. Halocin S8 eluted from the gel filtration column at about 4 kDa, which is near the lower limit of the reported resolution of ∼2.5 kDa for the matrix (Fig. 1B). This was unexpected given that HalS8 was retained by a filter with an NMWCO of 30 kDa (see Discussion), but it was not inconsistent with the range of protein sizes present in this retentate as observed by SDS-PAGE. SDS-PAGE analysis indicated that the gel filtration fractions that contained maximal activity were enriched for a protein of approximately 4 kDa (Fig. 1A, lane 2). Separation of the pooled and concentrated P30M gel filtration column fractions containing halocin activities of >2,048 AU using reversed-phase HPLC (step 3) completed the purification. Halocin activity eluted from the column at 62% acetonitrile (Fig. 1C), indicating that HalS8 is relatively hydrophobic. SDS-PAGE of HPLC reversed-phase fractions containing activity revealed a single band at ∼4 kDa (Fig. 1, lane 3).

Amino acid sequencing of HalS8 by Edman degradation revealed a hydrophobic (47%), 36-amino-acid protein of 3,580 Da with the following sequence: H2N-S-D-C-N-I-N-S-N-T-A-A - D - V - I - L - C - F - N - Q - V - G - S - C - A - L - C - S - P - T - L - V - G - G - G - V - P-COOH. Significantly, a methionine residue was absent from the amino terminus (Fig. 2 and see also below).

halS8 gene.

A 2,873-bp PstI/EcoRV fragment containing the entire halS8 gene was cloned and sequenced. The derived amino acid sequence for the 933-bp open reading frame contains a 36-amino-acid region with 97% identity (35 of 36 correct matches) to the sequence for HalS8 determined by Edman degradation (Fig. 2). The derived sequence differs from the Edman degradation sequence by a single residue at position 34 (a proline instead of a glycine). The molecular mass of HalS8 is 3,580 Da, making it the first “microhalocin” to be discovered. DNA sequencing revealed that the HalS8 peptide is processed (through an unknown mechanism) from within a much larger protein (Fig. 2). There are 230 amino acids upstream of HalS8 and 45 amino acids downstream.

The start site of transcription, as determined by fluorescent-primer extension, is coincident with the adenine of the AUG start codon for the 933-bp open reading frame and represents yet another example of a haloarchaeal “leaderless” transcript (3, 4, 6, 8, 30). Inspection of the DNA sequence upstream of the transcriptional start site revealed a haloarchaeal promoter hexamer (5′-ATTTAT-3′) located from −29 to −24 bp 5′ proximal to the start site (Fig. 2). This sequence matches the haloarchaeal consensus sequence (−29 TTTWWW −24) in five of six residues (36, 37). In addition, a transcription factor B recognition element is also present 5-bp upstream of the promoter at positions −34 and −35 (5′-AG-3′; Fig. 2).

halS8 gene expression.

Figure 3 correlates growth with both halocin activity and halS8 gene expression. Halocin S8 activity was undetectable throughout exponential growth until the culture began the transition into stationary phase. At this point, halocin activity levels increased dramatically and reached maximum within 10 h. Maximum levels remained constant throughout stationary phase. Initially, halS8 transcript levels paralleled HalS8 activity: transcript levels were at a very low basal level when halocin activity was undetectable and then increased ninefold and in parallel with halocin activity. However, when halS8 transcript levels were highest (time points 4 to 7, Fig. 3), the halocin activity remained unchanged. After remaining at maximal levels for 13 h, halS8 transcripts fell back rapidly to preinduced, exponential-phase basal levels.

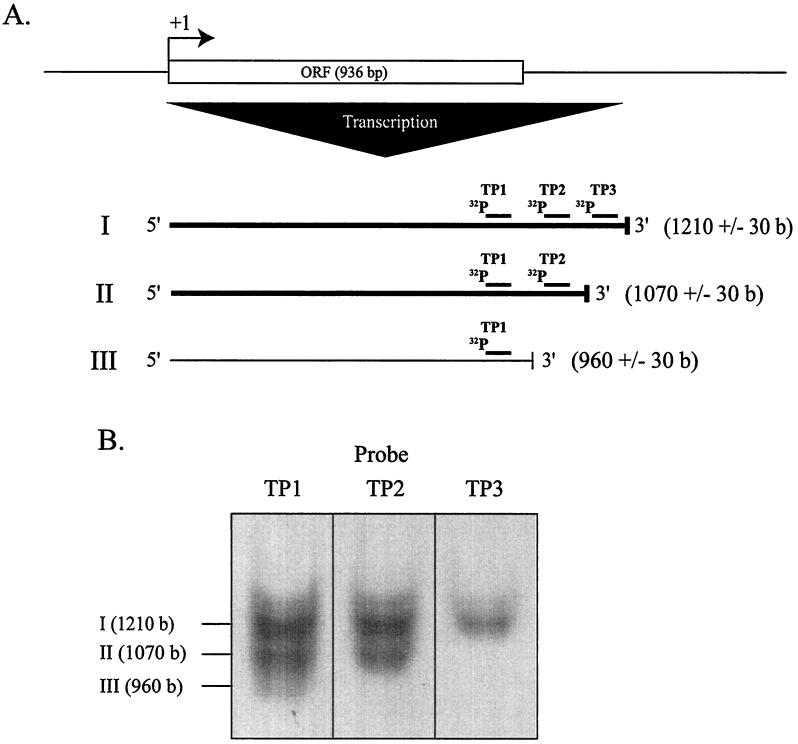

halS8 transcript termination and processing.

The inset to Fig. 3 shows a Northern blot prepared with total RNA taken from 14 time points throughout the S8a growth curve and probed with 32P-labeled probes from both the halS8 gene and the 7S RNA gene (see Materials and Methods). The halS8 probe hybridized with not one, but two major transcripts (∼1,070 and ∼1,210 [±30] bases) that showed identical expression profiles (Fig. 3). Detailed probing of the 3′ end of the transcripts actually revealed three different sizes (Fig. 4). The most abundant were 1,070 and 1,210 bases in length, while the smallest (960 ± 30 bases) was much less abundant. Only one haloarchaeal “T-tract” transcriptional termination sequence (5′-TTTAT-3′; Fig. 2 [13]), starting at position 1,266 is present, and its location roughly corresponds to the size of transcript “I” (1,210 bases) present on the Northern blot (Fig. 4). No stem-loop terminators are present at the 3′ end of the transcript. Probing immediately upstream of the start site resulted in no signal, confirming that the origin of the size variation was at the 3′ end and that the halS8 gene was under control of a single promoter (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Location of the 3′ ends of halS8 transcripts. (A) The diagram depicts the location of the three probes (TP1, TP2, and TP3) relative to the halS8 open reading frame. (B) Northern blots for each of the probes (see Fig. 2) and transcripts I, II, and III to which they hybridize. Size estimates for the transcripts are indicated to within the resolution of the gel (∼30 bases).

Location of the halS8 gene in the genome.

CHEF gel electrophoresis of total genomic DNA revealed one megaplasmid of ∼200 bp in addition to the chromosome. Southern analysis showed the halS8 gene to be present on the plasmid and not on the chromosome (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

Although halocin production is a nearly universal feature of haloarchaeal rods (40), HalS8 is only the second halocin to be characterized at the protein, gene, and transcript levels. Both halocin H4 (the first halocin to be characterized [6, 16]) and HalS8 have leaderless transcripts, share a plasmidal location, and exhibit a nearly identical pattern of gene expression.

In contrast to the 34.9-kDa mature form of halocin H4 (6), the 3.58-kDa HalS8 is a microhalocin (the haloarchaeal equivalent to a bacterial microcin). The fact that it is synthesized as part of a 311-amino-acid pro-protein and requires processing at two different sites is unusual for a peptide antibiotic but is reminiscent of inteins. However, inspection of the two cleavage sites on either side of the HalS8 peptide reveals that the residues required to perform an intein cleavage on the C-terminal side of HalS8 are absent (23). In addition, internal cleavage products that are removed during intein splicing are nonfunctional. Alternatively, the functional HalS8 protein may be cleaved from the larger pro-protein by one or more as-yet-uncharacterized haloarchaeal proteases. Indeed, the maturation of some bacterial microcins (e.g., microcin B17) requires the removal of the amino terminus by dedicated cleavage proteins (42). Given the lack of characterized sites for haloarchaeal proteases, it was not surprising that theoretical protease mapping of the entire derived amino acid sequence of the halS8 open reading frame failed to reveal canonical protease cleavage sites around either end of the HalS8 peptide.

BLAST searches of the NCBI databases lent little to the understanding of the amino acid sequences upstream and downstream of the HalH4 peptide. Unlike halocin H4, which contains a signal peptide that is removed (6), there is no such identifiable feature in the amino-terminal peptide, and this suggests a mechanism of translocation other than that involving the haloarchaeal sec-dependent pathway. This region still may be required for translocation across the haloarchaeal membrane, assuming that the halocin is externalized in such a fashion: some bacteriocins (especially colicins) are released through lysis of a small proportion of the total culture population (5, 11). Indeed, lysates of washed S8a cells actively making halocin produce zones of inhibition on sensitive lawn cells (data not shown). If the removal of the HalS8 peptide from the pro-protein leaves an intact 230-amino-acid peptide from the amino-terminal side and an intact 45-amino-acid peptide from the carboxy-terminal side, what might be their functions, if any (i.e., other than serving as a scaffold for presenting the halocin peptide for excision by proteolysis)? An intriguing scenario encompassing all three peptides has not escaped our notice. In addition to the halocin peptide, the amino-terminal protein might function as the immunity protein, which protects the producer from the action of its own halocin. In Bacteria, it is typical to find genes coding for immunity proteins adjacent to the bacteriocins from which they provide protection. However, all examples of bacterial immunity proteins to date are encoded by separate genes (9, 10, 14, 15, 20, 27, 35). The role of the small, 45-amino-acid carboxy-terminal peptide might then be as an autoinducer or peptide pheromone (12). In any event, antibodies to these peptides and Western blots are needed to determine if they exist as intact peptides.

Throughout the purification and characterization of the HalS8 protein, all data were consistent with a protein of approximately 4 kDa, with the exception of the datum from the final step in TFF: HalS8 activity was equally partitioned between the retentate and the filtrate after filtration through the 30-kDa NMWCO filter. The fact that a protein of about 4 kDa was significantly retained by a 30-kDa NMWCO tangential-flow filter was unexpected, and two factors working together and unique to this work could have produced this result: (i) increased surface tension and viscosity due to the presence of 4 M NaCl in the medium and (ii) the highly hydrophobic nature of the mature peptide. Since these factors were also present during gel filtration column chromatography, which produced data consistent with a 4-kDa protein, one must suspect conditions specific to the TFF procedure: regenerated cellulose membrane, high pressure, and rapid flow rate. SDS-PAGE analysis of the 30-kDa TFF retentate shows that many proteins were in fact less than 30 kDa (8 to 20 kDa); therefore, the tangential-flow data were given little weight in estimating the size of the HalS8 protein.

The regulatory region of the halS8 gene contains a typical haloarchaeal promoter (Fig. 2) (7, 22, 36, 37), and primer extension reveals a single start site coincident with the 5′ ATP of the AUG start codon on the “leaderless” mRNA transcript. Although the halS8 gene is regulated and induced at the onset to stationary phase, further inspection of the regulatory region revealed no clues as to sequences specific to haloarchaeal stationary-phase gene expression. Given that the haloarchaea possess a simplified version of the eukaryotic RNA polymerase II basal transcription apparatus (38; Palmer et al., Abstr. 97th Gen. Meet. Am. Soc. Microbiol.), it is not surprising that the initial patterns of halS8 and halH4 gene expression involve the production of “basal” levels of transcripts prior to induction (Fig. 3 [6]): the eukaryotic RNA polymerase II basal transcription apparatus is able to accurately direct low levels of transcription in vitro (29). As mentioned above, the pattern of gene expression for halS8 and halH4 are identical (including the small dip in levels during maximum expression) and, initially at least, the transcript levels correlate well with halocin activity. However, shortly after maximal transcript levels are reached, halocin activity plateaus, while transcripts remain high (Fig. 3), suggesting that the translation of these transcripts, although abundant, is inhibited. Lastly, in the absence of haloarchaeal transcription inhibitors, we are unable to conduct mRNA half-life experiments in order to distinguish between transcript turnover and new synthesis.

The presence of two abundant and one minor halS8 transcript on the Northern blot was unexpected and different from the single transcript produced by the halH4 gene (Fig. 3 [6]). The primer extension data provided no evidence of more than one start site, and the virtually identical regulation of the two most abundant transcripts is not consistent with the presence of a second (slightly different) copy of the gene somewhere else in the genome. Additionally, Southern hybridization showed only a single copy of the gene (data not shown). Inspection of the 3′ sequence distal to the stop codon revealed no stem-loop structures and only a single haloarchaeal “T-tract” terminator (5′-TTTAT-3′), which is tied for the lowest efficiency of termination among the four terminators (T5 > T4 > TCTTT = TTTA/CT [13]). Therefore, three oligonucleotide probes were designed and directed against the 3′ end of the transcript (Fig. 2 and 4). This experiment revealed that length variations resulted from either differential termination, posttranscriptional processing, or both.

Significance.

The characterization of halocins in general (6, 34) and the HalS8 protein and the halS8 gene specifically have provided models for multiple avenues of study in the haloarchaea: (i) regulation of stationary-phase gene expression; (ii) both sec-dependent and non-sec-dependent protein translocation; (iii) protein processing; (iv) mRNA termination and/or processing; (v) posttranscriptional control of translation; and (vi) initiation of translation from leaderless transcripts. In addition, the basis for halocin immunity has yet to be elucidated for any halocin and, except for halocin H6 (18), the mechanism(s) of action is unknown. With respect to HalS8, the high level of hydrophobicity (47%) suggests that this antibiotic may interact with the membrane of the target organism. Consequently, given the potential vastness of halocin diversity, halocins will provide a source of novel and interesting discoveries for years to come.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by Public Health Service grant GM52660 from the National Institutes of Health and by Organized Research of Northern Arizona University.

We thank Penny Amy for supplying strain S8a; Peter Jablonski for supplying haloalkaliphilic strains; Kathleen Danna for quantifying transcript levels; PPG Industries for their gift of MAZU DF 204 antifoam; Elizabeth O'Connor for assistance and advice on protein purification; Jörg Soppa for helpful discussions on haloarchaeal promoters; and Drew Kamadulski, Jim Schupp, Kimothy Smith, and Gordon Southam for technical assistance and advice.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ausubel F, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K, editors. Current protocols in molecular biology. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons; 1998. pp. 6.4.1–6.4.10. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barefoot S F, Harmon K M, Grinstead D A, Nettles C G. Bacteriocins, molecular biology. In: Lederberg J, editor. Encyclopedia of microbiology. Vol. 1. New York, N.Y: Academic Press, Inc.; 1992. pp. 191–202. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Betlach M C, Friedman J, Boyer H W, Pfeifer F. Characterization of a halobacterial gene affecting bacterio-opsin gene expression. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;20:7949–7959. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.20.7949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blank A, Oesterhelt D. The halo-opsin gene. II. Sequence, primary structure of halorhodopsin and comparison with bacteriorhodopsin. EMBO J. 1987;6:265–273. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb04749.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Braun V, Pilsl H, Gross P. Colicins: structures, modes of action, transfer through membranes, and evolution. Arch Microbiol. 1994;161:199–206. doi: 10.1007/BF00248693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheung J, Danna K J, O'Connor E M, Price L B, Shand R F. Isolation, sequence, and expression of the gene encoding halocin H4, a bacteriocin from the halophilic archaeon Haloferax mediterranei R4. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:548–551. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.2.548-551.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Danner S, Soppa J. Characterization of the distal promoter element of halobacteria in vivo using saturation mutagenesis and selection. Mol Microbiol. 1996;19:1265–1276. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02471.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DasSarma S, RajBhandary U L, Khorana H G. Bacterio-opsin mRNA in wild-type and bacterio-opsin-deficient Halobacterium halobium strains. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:125–129. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.1.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garrido M C, Herrero M, Kolter R, Moreno F. The export of the DNA replication inhibitor Microcin B17 provides immunity for the host cell. EMBO J. 1988;7:1853–1862. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb03018.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.González-Pastor J E, San Millán J L, Castilla M A, Moreno F. Structure and organization of plasmid genes required to produce the translation inhibitor microcin C7. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:7131–7140. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.24.7131-7140.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoover D G. Bacteriocins: activities and applications. In: Lederberg J, editor. Encyclopedia of microbiology. Vol. 1. New York, N.Y: Academic Press, Inc.; 1992. pp. 181–190. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kleerebezem M, Quadri L E N, Kuipers O P, deVos W M. Quorum sensing by peptide pheromones and two-component signal-transduction systems in gram-positive bacteria. Mol Microbiol. 1997;24:895–904. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.4251782.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuo Y-P. In vivo characterization of archaeal transcription termination signals and characterization of a Haloferax volcanii heat shock gene: a model for gene regulation. Ph.D. thesis. Columbus: The Ohio State University; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kurepina N E, Basyuk E I, Metlitskaya A Z, Zaitsev D A, Khmel I A. Cloning and mapping of the genetic determinants for microcin C51 production and immunity. Mol Gen Genet. 1993;241:700–706. doi: 10.1007/BF00279914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lagos R J, Villanueva E, Monasterio O. Identification and properties of the genes encoding microcin E492 and its immunity protein. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:212–217. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.1.212-217.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meseguer I, Rodriguez-Valera F. Production and purification of halocin H4. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1985;28:177–182. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meseguer I, Rodriguez-Valera F, Ventosa A. Antagonistic interactions among halobacteria due to halocin production. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1986;36:177–182. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meseguer I, Torreblanca M, Rodriguez-Valera F. Specific inhibition of the halobacterial Na+/H+ antiporter by halocin H6. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:6450–6455. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.12.6450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miercke L J W, Ross P E, Stroud R M, Dratz E A. Purification of bacteriorhodopsin of mature and partially processed forms. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:7531–7535. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moreno F, San Millán J L, Hernández-Chico C, Kolter R. Microcins. In: Vining L C, Stuttard C, editors. Genetics and biochemistry of antibiotic production. Newton, Mass: Butterworth-Heinemann; 1995. pp. 307–321. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morrissey J H. Silver stain for proteins in polyacrylamide gels: a modified procedure with enhanced uniform sensitivity. Anal Biochem. 1981;117:307–310. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(81)90783-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Palmer J R, Daniels C J. In vivo definition of an archaeal promoter. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:1844–1849. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.7.1844-1849.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Perler F B. InBase, the New England Biolabs Intein Database. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:346–347. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.1.346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pfeifer F, Betlach M. Genome organization in Halobacterium halobium: a 70-kb island of more (AT) rich DNA in the chromosome. Mol Gen Genet. 1985;198:449–455. doi: 10.1007/BF00332938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Prangishvili D, Holz I, Stieger E, Nickell S, Kristjansson J K, Zillig W. Sulfolobicins, specific proteinaceous toxins produced by strains of the extremely thermophilic archaeal genus Sulfolobus. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:2985–2988. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.10.2985-2988.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rdest U, Sturm M. Bacteriocins from halobacteria. In: Burgess R, editor. Protein purification: micro to macro. New York, N.Y: Alan R. Liss, Inc.; 1987. pp. 271–278. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rodriguez E, Lavina M. Genetic analysis of microcin H47 immunity. Can J Microbiol. 1998;44:692–697. doi: 10.1139/cjm-44-7-692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rodriguez-Valera F, Juez G, Kushner D J. Halocins: salt-dependent bacteriocins produced by extremely halophilic rods. Can J Microbiol. 1982;28:151–154. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roeder R G. The role of general initiation factors in transcription by RNA polymerase II. Trends Biochem Sci. 1996;21:325–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ruepp A, Soppa J. Fermentative arginine degradation in Halobacterium salinarium (formerly Halobacterium halobium): genes, gene products, and transcripts of the arcRABC gene cluster. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:4942–4947. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.16.4942-4947.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schagger H, von Jagow G. Tricine-sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis for the separation of proteins in the range from 1 to 100 kDa. Anal Biochem. 1987;166:368–379. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90587-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shand R F, Betlach M C. Expression of the bop gene cluster of Halobacterium halobium is induced by low oxygen tension and by light. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:4692–4699. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.15.4692-4699.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shand R F, Price L B, O'Connor E M. Halocins: protein antibiotics from hypersaline environments. In: Oren A, editor. Microbiology and biogeochemistry of hypersaline environments. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press LLC; 1999. pp. 195–306. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Solbiati J O, Ciaccio M, Farías R N, González-Pastor J E, Moreno F, Salomón R A. Sequence analysis of the four plasmid genes required to produce the circular peptide antibiotic microcin J25. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:2659–2662. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.8.2659-2662.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Soppa J. Normalized nucleotide frequencies allow the definition of archaeal promoter elements for different archaeal groups and reveal base-specific TFB contacts upstream of the TATA box. Mol Microbiol. 1999;31:1589–1592. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01274.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Soppa J. Transcription initiation in Archaea: facts, factors and future aspects. Mol Microbiol. 1999;31:1295–1305. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01273.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Soppa J, Link T A. The TATA-box-binding protein (TBP) of Halobacterium salinarum: cloning the tbp gene, heterologous production of TBP and folding of TBP into a native configuration. Eur J Biochem. 1997;249:318–324. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.t01-1-00318.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Torreblanca M, Meseguer I, Rodriguez-Valera F. Halocin H6, a bacteriocin from Haloferax gibbonsii. J Gen Microbiol. 1989;135:2655–2661. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Torreblanca M, Meseguer I, Ventosa A. Production of halocin is a practically universal feature of archaeal halophilic rods. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1994;19:201–205. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Woese C R, Kandler O, Wheelis M L. Towards a natural system of organisms: proposal for the domains Archaea, Bacteria, and Eucarya. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:4576–4579. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yorgey P, Davagnino J, Kolter R. The maturation pathway of microcin B17, a peptide inhibitor of DNA gyrase. Mol Microbiol. 1993;9:897–905. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01747.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]