Abstract

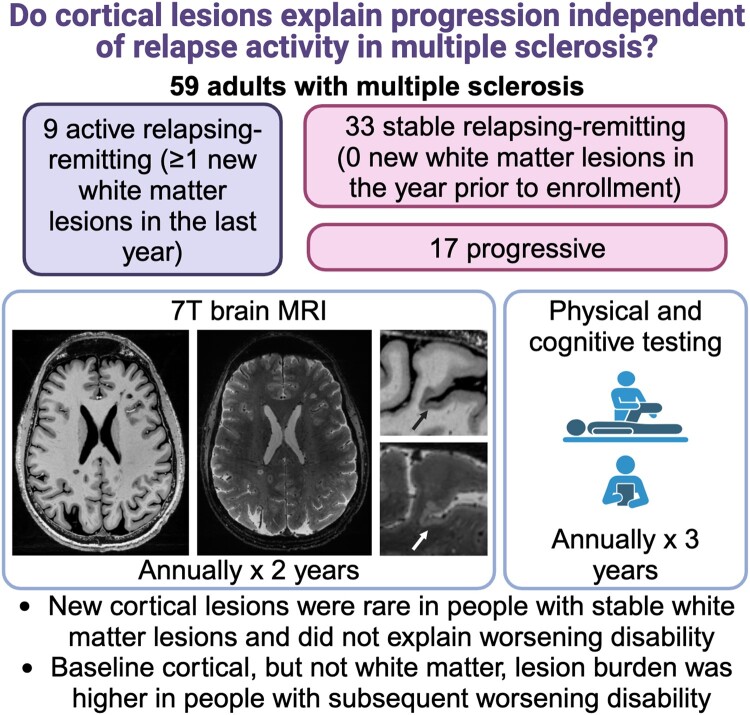

Cortical lesions are common in multiple sclerosis and are associated with disability and progressive disease. We asked whether cortical lesions continue to form in people with stable white matter lesions and whether the association of cortical lesions with worsening disability relates to pre-existing or new cortical lesions.

Fifty adults with multiple sclerosis and no new white matter lesions in the year prior to enrolment (33 relapsing-remitting and 17 progressive) and a comparison group of nine adults who had formed at least one new white matter lesion in the year prior to enrolment (active relapsing-remitting) were evaluated annually with 7 tesla (T) brain MRI and 3T brain and spine MRI for 2 years, with clinical assessments for 3 years. Cortical lesions and paramagnetic rim lesions were identified on 7T images.

Seven total cortical lesions formed in 3/30 individuals in the stable relapsing-remitting group (median 0, range 0–5), four total cortical lesions formed in 4/17 individuals in the progressive group (median 0, range 0–1), and 16 cortical lesions formed in 5/9 individuals in the active relapsing-remitting group (median 1, range 0–10, stable relapsing-remitting versus progressive versus active relapsing-remitting P = 0.006). New cortical lesions were not associated with greater change in any individual disability measure or in a composite measure of disability worsening (worsening Expanded Disability Status Scale or 9-hole peg test or 25-foot timed walk). Individuals with at least three paramagnetic rim lesions had a greater increase in cortical lesion volume over time (median 16 µl, range −61 to 215 versus median 1 µl, range −24 to 184, P = 0.007), but change in lesion volume was not associated with disability change. Baseline cortical lesion volume was higher in people with worsening disability (median 1010 µl, range 13–9888 versus median 267 µl, range 0–3539, P = 0.001, adjusted for age and sex) and in individuals with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis who subsequently transitioned to secondary progressive multiple sclerosis (median 2183 µl, range 270–9888 versus median 321 µl, range 0–6392 in those who remained relapsing-remitting, P = 0.01, adjusted for age and sex). Baseline white matter lesion volume was not associated with worsening disability or transition from relapsing-remitting to secondary progressive multiple sclerosis.

Cortical lesion formation is rare in people with stable white matter lesions, even in those with worsening disability. Cortical but not white matter lesion burden predicts disability worsening, suggesting that disability progression is related to long-term effects of cortical lesions that form early in the disease, rather than to ongoing cortical lesion formation.

Keywords: multiple sclerosis, MRI, cortical lesions, neuroimaging

Beck et al. report the results of a longitudinal 7T MRI study of 59 adults with multiple sclerosis. They find that new cortical lesion formation is rare in people with multiple sclerosis with stable white matter lesions but that cortical lesion burden predicts subsequent disability worsening over 3 years.

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

Introduction

In multiple sclerosis, there can be gradual accrual of disability over time, often in the absence of new white matter or spinal cord lesions. This accrual of disability may be related to long-term effects of focal demyelination that occurs early in the disease, persistent inflammation either diffusely or within pre-existing lesions, and/or ongoing focal demyelination that is not detected on standard MRI, including in the cerebral cortex.1,2

Cortical multiple sclerosis lesions are associated with disability and progression, possibly to a greater extent than white matter lesions.3-6 Cortical lesions, and in particular subpial cortical lesions, which involve the superficial cortical layers, have been hypothesized to form via a partially distinct mechanism from other multiple sclerosis lesions that is related to inflammation in the overlying meninges.7-9 Despite their acknowledged prevalence on histopathologic studies, where a median of 14% of the cortex is demyelinated,10-12 cortical lesions have until recently been difficult to visualize on in vivo MRI. This has limited our understanding of when they develop and how they contribute to disability. Specifically, it is unclear whether the association between cortical lesions and progression is due to a persistent and long-term effect of cortical lesions that form early in the disease course or to ongoing cortical lesion formation in later stages of the disease. Intriguingly, recent studies have indicated that cortical lesion formation may be higher in progressive multiple sclerosis than in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis,13,14 in contrast to white matter lesion formation, the vast majority of which occurs in the relapsing phase of the disease.

Limited data exist, however, on whether cortical lesions, detected with sensitive 7 tesla (T) MRI methods, continue to form in people on moderate and high-efficacy disease-modifying therapies and if so whether new cortical lesions contribute to ongoing accrual of disability. The formation of new cortical lesions in people with stable white matter lesions could have important implications for treatment.

In this study, we followed three groups longitudinally people in whom new white matter lesions had formed in the year prior to their enrolment (active relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis), people with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis with stable white matter lesions in the year prior to enrolment (stable relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis) and people with progressive multiple sclerosis with stable white matter lesions in the year prior to enrolment with the goal of determining whether cortical lesions continue to form in people with stable white matter lesions and whether the association of cortical lesions with worsening disability is related to pre-existing or new cortical lesions.

Materials and methods

Clinical cohort

Participants enrolled in an institutional review board-approved multiple sclerosis natural history study at the National Institutes of Health provided written, informed consent. We built a prospective subcohort of multiple sclerosis patients who were ≥18 years old and without 7T MRI contraindication. Between May 2017 and November 2018, we prospectively enrolled individuals with stable white matter and spinal cord lesions by 3T MRI in the year prior to enrolment (stable multiple sclerosis), including 36 with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis and 19 with progressive multiple sclerosis (15 secondary progressive multiple sclerosis and four primary progressive multiple sclerosis). For comparison, we also enrolled nine individuals with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis who had at least one new or contrast-enhancing white matter lesion in the year prior to enrolment (active multiple sclerosis). As we did not have any data on the rate of cortical lesion accumulation using our more sensitive 7T techniques at the time the study was initiated, the sample size was driven by recruitment feasibility in our centre, and we prioritized recruiting participants with radiographically stable multiple sclerosis.

Participants were evaluated annually. For the first 2 years, study visits included a clinical history and physical exam, Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS), Paced Auditory Symbol Addition Test (PASAT), Symbol Digit Modalities Test (SDMT, paper based), 25-foot timed walk (25FTW), 9-hole peg test (9HPT), a 7T brain MRI and a 3T brain and spinal cord MRI. If 3- and 7T visits were obtained more than 1 day apart, the 25FTW and 9HPT were performed at both visits, and results were averaged. After the first 2 years, participants were followed annually with the same clinical testing for one additional year. Clinical relapses were determined based on chart review by a multiple sclerosis specialist.

MRI acquisition

All 3T scans were acquired on a single Magnetom Skyra scanner (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany), equipped with a 32-channel head coil, used when imaging only the brain, and a 20-channel head–neck coil when imaging the brain and spine in a single session (see Supplementary Table 1 for full sequence parameters). 3T brain scans included axial 2D proton density/T2w (0.34-mm in-plane resolution, 3-mm slice thickness), sagittal 3D magnetization prepared 2 rapid acquisition gradient echo (MP2RAGE, 1-mm isometric) and sagittal 3D T2w fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (1-mm isometric) before and after administration of gadobutrol (unless contraindicated or refused by the participant). Several upgrades to the MP2RAGE version on the 3T scanner occurred in the first year of the study, after which there were no further changes in the MP2RAGE version. There were no changes to the sequence parameters with these upgrades. Spinal cord scans included sagittal 2D short-tau inversion recovery (STIR, 0.5 mm in plane, 1.4-mm slice thickness) and sagittal 3D T1-weighted (T1w) gradient-recalled echo (GRE, 1-mm isometric), sagittal 3D MP2RAGE of the cervical spine (1 mm isometric) and axial 3D MP2RAGE of the thoracic spine (0.8 mm in plane, 4-mm slice thickness).

All 7T brain scans were performed on a 7T whole-body research system (Siemens) equipped with a single-channel transmit, 32-channel phased array receive head coil (see Supplementary Table 1 for full sequence parameters). A software upgrade (B17 to E12) was performed prior to the final five Year 2 scans. 7T scans included axial 3D MP2RAGE (0.5-mm isometric, acquired four times per scan session), sagittal 3D MP2RAGE (0.7-mm isometric) and sagittal 3D segmented T2*-weighted (T2*w) echo-planar imaging (0.5-mm isometric, acquired in two partially overlapping volumes for full brain coverage). At the baseline and Year 1 time points, axial 2D T2*w multi-echo GRE was also acquired. At Year 2 time point, for 30 scans (all scans acquired after April 2020), an axial 3D T2*w multi-echo GRE with navigator-based B0 and motion correction was acquired in place of the 2D T2*w multi-echo GRE, as we found that this sequence improved image quality.15,16 Both types of T2*w GRE scans were 0.5-mm isometric and acquired in three partially overlapping volumes for near full supratentorial brain coverage. MP2RAGE data were processed into uniform denoised images (hereafter T1w MP2RAGE) and T1 maps using manufacturer-provided software. 7T images did not fully cover the inferior temporal and occipital lobes.

The median interval between 3- and 7T MRI was 27 days [interquartile range (IQR) 61, range 1–294].

Image processing

The 7T 0.5-mm T1w and T1 map MP2RAGE repetitions were co-registered, and median T1w and T1 map images were generated, as described previously.17 The 7T T2*w GRE magnitude images were averaged across echo times, and within each time point, the averaged GRE images and the T2*w echo-planar imaging images were linearly registered (FMRIB’s Linear Image Registration Tool, FLIRT18,19) to the 7T T1w MP2RAGE median images. For the Year 1 and Year 2 time points, 7T T1 MP2RAGE median images were then registered to the baseline T1w MP2RAGE (Analysis of Functional NeuroImages, AFNI, 3DAllineate20,21), and the transformation matrix was applied to the T2*w echo-planar imaging and GRE magnitude images. Weighted sinc interpolation was used to reduce smoothing artefacts and preserve image consistency across time points. Subtraction images were generated between registered T1 map images at each time point.

Baseline 3T images were processed and registered as described previously.22 For follow-up time points, fluid-attenuated inversion recovery images were registered to T1w MP2RAGE (FLIRT), followed by registration of all fluid-attenuated inversion recovery and T1w MP2RAGE to the baseline T1w MP2RAGE (AFNI, 3DAllineate).

Longitudinal cortical and white matter lesion segmentation

Cortical lesions were manually segmented on baseline images using median 7T T1w and T1 map MP2RAGE, T2*w GRE and T2*w echo-planar imaging images by two independent raters (J.M., 19 years of experience in multiple sclerosis neuroimaging, and E.S.B., 3 years of experience) for each case followed by a consensus review by both raters, as previously described.23 Lesions were categorized as leukocortical (Type 1, involving the cortex and white matter), intracortical (Type 2, confined to the cortex and not touching the pial surface of the brain) and subpial (Type 3, involving the cortex exclusively and touching the pial surface, and Type 4, involving the cortex and the white matter and touching the pial surface).10 Cortical lesions were hypointense on T1w MP2RAGE images and/or hyperintense on T2*w images and were seen on at least two consecutive axial slices. Cortical lesion volumes and median T1 within lesions, including the white matter portion of leukocortical lesions, were calculated.

For each subsequent time point, MP2RAGE and T2*w images were evaluated for the presence of new cortical lesions compared with the baseline scan. One rater (either S.F. or W.A.M., each with 1 year of experience in multiple sclerosis neuroimaging) evaluated each case for new cortical lesions. E.S.B. then reviewed and confirmed any new lesions identified by the first rater and reviewed the images for any additional new lesions. Cortical lesions that were visible at Year 1 or 2 and whose presence at earlier time points was potentially obscured by motion were not segmented. In addition, the mask for each cortical lesion present at baseline was evaluated and adjusted at each time point for both imperfect registration and changes in lesion size. The change in volume of each cortical lesion was calculated. The total change in cortical lesion volume and percentage change in cortical lesion volume for each participant was calculated, considering all lesions present at baseline.

White matter lesions were segmented on baseline 3T images as previously described.23 Baseline white matter lesion masks were adjusted using registered Year 2 T1w MP2RAGE and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery images, and new lesions were identified and segmented. Longitudinal 7T MP2RAGE images were also assessed for new white matter lesions. Occasionally, small, new white matter lesions were identified only on 7T images but were seen in retrospect on 3T images. Once identified on 7T images, these new lesions were segmented on the corresponding 3T images.

Baseline 7T T2*w GRE phase images were processed as previously described24 and evaluated for the presence of supratentorial chronic active, or paramagnetic rim, lesions (defined as having a hypointense rim with internal isointensity relative to extralesional white matter) independently by E.S.B. and S.F., followed by a consensus review. Seven of the participants were not evaluated for paramagnetic rim lesions due to motion degradation or incomplete brain coverage of phase images.

Spinal cord lesion assessment

Spinal cord lesions were identified by two independent raters followed by a consensus review using sagittal STIR and MP2RAGE images of the cervical spinal cord and sagittal STIR and axial MP2RAGE images of the thoracic spinal cord at baseline and Year 2.

Brain volume measurement

Brain tissue segmentation was performed on baseline 0.7-mm T1w MP2RAGE images, which were available for 48 participants. White matter lesion masks generated using 3T images were registered to 7T space (Advanced Normalization Tools),25 and lesion filling was performed using FMRIB Software Library.26 Whole brain, cortex, white matter and deep grey matter volumes were extracted using SynthSeg.27 Baseline brain volumes were normalized using the MNI152 intracranial volume (https://nist.mni.mcgill.ca/icbm-152lin/).

Statistical analyses

Comparisons between stable relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis and progressive multiple sclerosis and between people with stable versus new lesions were performed using t-tests, Fisher’s exact test and Mann–Whitney tests as appropriate.

Comparisons between active relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis, stable relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis and progressive multiple sclerosis were performed using Kruskal–Wallis tests and one-way ANOVA as appropriate.

To investigate the relationship between MRI measures and subsequent disability change, we first performed Box–Cox transformation of changes in disability measures and lesion counts and volumes and then calculated partial correlation coefficients, adjusting for age and sex, with 5000 nonparametric bootstrapping iterations to increase analysis robustness.28,29

Comparisons between people with progression of disability, defined as an increase in EDSS of ≥1.0 for baseline EDSS <6.0 or ≥0.5 for baseline EDSS ≥6.0 or 20% increase in 25FTW or 20% increase in 9HPT, versus stable disability and between people who transitioned from relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis to secondary progressive multiple sclerosis versus those who remained relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis were performed using a multivariable general linear model adjusted for age and sex. Box–Cox transformation of lesion counts and volumes was performed prior to running these models.

Adjustment for multiple comparisons was performed using the Benjamini and Hochberg procedure.30 Statistical analyses were performed on IBM SPSS Statistics, version 26 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Cortical lesion formation is rare in people with stable white matter lesions

Sixty-four individuals with multiple sclerosis, including nine active relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis, 36 stable relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis and 19 progressive multiple sclerosis (15 secondary progressive multiple sclerosis and four primary progressive multiple sclerosis), underwent baseline clinical evaluation, 3T brain and spinal cord MRI and 7T brain MRI. The results of the baseline analyses have been previously described23; 59/64 participants (92%) returned for at least one 7T follow-up visit [nine active relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis, 33 stable relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis and 17 progressive multiple sclerosis (14secondary progressive multiple sclerosis and three primary progressive multiple sclerosis)] (Table 1). Mean ± SD total 7T follow-up was 2 ± 0.5 years and did not differ between groups (P = 0.77).

Table 1.

Baseline cohort characteristics

| Active relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (n = 9) | Stable relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (n = 33) | Progressive multiple sclerosis (n = 17) | P-value stable relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis versus progressive multiple sclerosis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Femalea | 6, 67% | 22, 67% | 11, 65% | >0.99b |

| Age (years)c | 46 ± 10 | 45 ± 11 | 57 ± 9 | 0.0005d,* |

| Disease durationc | 11 ± 9 | 11 ± 8 | 23 ± 11 | <0.0001d,* |

| 7T follow-up time (years)c | 1.9 ± 0.7 | 2.0 ± 0.4 | 1.9 ± 0.6 | 0.40d |

| Clinical follow-up time (years)c | 2.4 ± 0.9 | 3.0 ± 0.6 | 2.6 ± 0.7 | 0.07d |

| Disability measures | ||||

| EDSSe | 1.0, 1.5 (0–6.5) | 1.5, 1.0 (0–5.0) | 6.0, 3.0 (2.0–7.5) | <0.0001f,* |

| 25FTWc | 6.4 ± 6.0 | 4.7 ± 1.0 | 13.9 ± 11.9 | <0.0001d,* |

| 9HPTc | 20.0 ± 6.3 | 19.3 ± 3.1 | 37.8 ± 17.9 | <0.0001d,* |

| PASATc | 49 ± 6 | 53 ± 7 | 43 ± 12 | 0.0004d,* |

| SDMTc | 61 ± 16 | 58 ± 10 | 35 ± 14 | <0.0001d,* |

| Treatmenta | ||||

| None | 5, 56% | 4, 12% | 2, 12% | 0.62g |

| Injectable | 2, 22% | 6, 18% | 3, 18% | |

| Oral | 1, 11% | 15, 34% | 5, 29% | |

| Infusion | 1, 11% | 8, 24% | 7, 41% | |

| MRI measures | ||||

| Cortical lesionse | ||||

| Total cortical lesion number | 18, 71 (0–168) | 15, 22 (0–113) | 58, 100 (2–212) | 0.006f,* |

| Total cortical lesion volume (µl) | 530, 1488 (0–9888) | 375, 903 (0–6392) | 1268, 3310 (32–8918) | 0.04f |

| Leukocortical lesion number | 3, 10 (0–17) | 5, 12 (0–67) | 29, 37 (1–49) | 0.008f,* |

| Leukocortical lesion volume (µl) | 48, 165 (0–214) | 122, 368 (0–2818) | 553, 950 (11–1709) | 0.02f,* |

| Intracortical lesion number | 1, 7 (0–20) | 1, 2 (0–7) | 4, 8 (0–10) | 0.004f,* |

| Intracortical lesion volume (µl) | 3, 26 (0–65) | 4, 8 (0–34) | 11, 30 (0–71) | 0.02f,* |

| Subpial lesion number | 17, 49 (0–142) | 5, 10 (0–93) | 21, 52 (0–168) | 0.007f,* |

| Subpial lesion volume (µl) | 287, 1426 (0–9660) | 143, 429 (0–5233) | 505, 2403 (0–8015) | 0.02f,* |

| White matter lesion volume (ml)e | 4.2, 8.0 (1.8–26.5) | 6.5, 7.9 (0.9–49.9) | 13, 21 (1.6–63.1) | 0.01f,* |

| Spinal cord lesion numbere | 4, 6 (0–10) | 5, 7 (0–13) | 9.5, 7 (1–19) | 0.004f,* |

| Normalized brain volume (ml)c | ||||

| Whole brain | 1494 ± 62 | 1490 ± 38 | 1433 ± 15 | 0.026d,* |

| Deep grey matter | 72 ± 7 | 70 ± 5 | 63 ± 7 | 0.023d |

| Cortex | 663 ± 27 | 660 ± 19 | 648 ± 21 | 0.189d |

| White matter | 571 ± 28 | 566 ± 21 | 5364 ± 33 | 0.029d,* |

Active relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis was defined as the presence of a new or enhancing lesion on MRI in the year prior to enrolment in the study. Raw scores are used for all disability measures. Injectable: glatiramer acetate and interferons. Oral: dimethyl fumarate, fingolimod and teriflunomide. Infusion: daclizumab, natalizumab, ocrelizumab, rituximab.

25FTW, 25-foot timed walk; 9HPT: 9-hole peg test; EDSS, Expanded Disability Status scale; PASAT: Paced Auditory Serial Addition Test.

a n, %.

bFisher’s exact test.

cMean ± SD.

d t-test.

eMedian, interquartile range (range).

fMann–Whitney test.

gChi-square test.

*Significant after adjusting for false discovery rate.

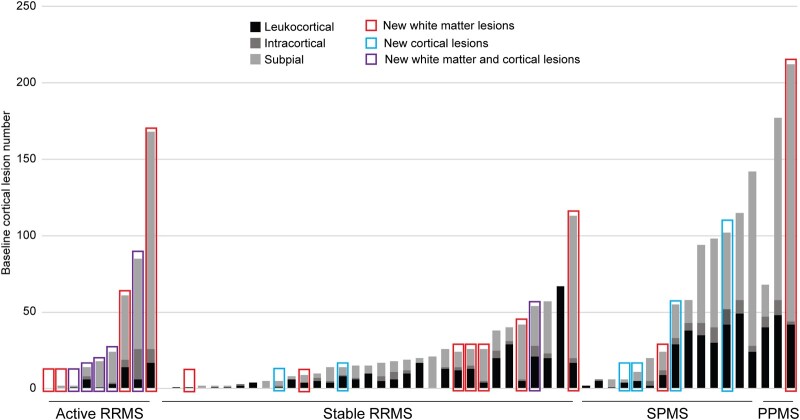

Twelve individuals formed at least one new cortical lesion, including 5/9 (56%) active relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis, 3/33 (9%) stable relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis and 4/17 (24%) progressive multiple sclerosis (P = 0.008, stable relapsing-remitting versus progressive multiple sclerosis P = 0.21). A total of 16 new cortical lesions formed in the active relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis group (median 1 per participant, IQR 2, range 0–10), seven in the stable relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis group (median 0, IQR 0, range 0–5) and four in the progressive multiple sclerosis group (median 0, IQR 1, range 0–1) (P = 0.006, stable relapsing-remitting versus progressive multiple sclerosis P = 0.88) (Fig. 1; Table 2). There was no difference in the subtypes of new cortical lesions (leukocortical, intracortical and subpial) between the three groups (P = 0.87).

Figure 1.

New cortical lesion formation is rare in people with stable white matter lesions. New cortical and white matter lesion formation was frequent (56 and 100%, respectively) in people with active relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (defined as having at least one new or enhancing white matter lesion in the year prior to enrolment) but was infrequent in people with radiographically stable relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (9% for cortical lesions, 24% for white matter lesions) or progressive multiple sclerosis (24% and 17%) (P = 0.008 for cortical lesions, P < 0.0001 for white matter lesions, chi-square test). New cortical lesion formation was not related to baseline cortical lesion number (median baseline cortical lesion number 16 versus median 20 for those without new cortical lesions, P = 0.97, Mann–Whitney test). Baseline cortical lesions are represented by grey bars; each bar represents a single participant. PPMS, primary progressive multiple sclerosis; RRMS, relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis; SPMS, secondary progressive multiple sclerosis.

Table 2.

Longitudinal MRI changes by multiple sclerosis phenotype

| Active relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (n = 9) | Stable relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (n = 33) | Progressive multiple sclerosis (n = 17) | P-value (active relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis versus stable relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis versus progressive multiple sclerosis) | P-value (stable relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis versus progressive multiple sclerosis) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cortical lesions | |||||

| Number of individuals with new lesionsa | 5 (56%) | 3 (9%) | 4 (24%) | 0.008b,* | 0.21c |

| New lesion numberd | 16, 1, 2 (0–10) | 7, 0, 0 (0–5) | 4, 0, 1 (0–1) | 0.006e,* | 0.88f |

| New lesion volume (µl)g | 3.5, 67.75 (0–484.4) | 0, 0 (0–51) | 0, 1 (0–19.25) | 0.020e | >0.99f |

| Change in lesion volume (µl)g | 7.8, 59.0 (−0.4 to 183.5) | 8.1, 33.7 (−60.6 to 121.8) | 22.1, 82.6 (−27.0 to 215.3) | 0.25e | 0.14f |

| % change in lesion volumeg | 3.4, 4.9 (−0.1 to 57.3) | 1.2, 6.8 (−4.7 to 27.6) | 1.5, 4.4 (−7.5 to 20.7) | 0.43e | >0.99f |

| % enlarging lesions | 11, 20 (0–100) | 9, 26 (0–100) | 8, 22 (0–40) | 0.80e | 0.52f |

| White matter lesions | |||||

| Number of individuals with new lesionsa | 9 (100%) | 8 (24%) | 2 (17%) | <0.0001b,* | 0.46f |

| New lesion numberd | 66, 2, 12 (1–31) | 27, 0, 1 (0–9) | 3, 0, 0 (0–2) | <0.0001e,* | >0.99f |

| New lesion volume (µl)g | 87, 358 (0–675) | 0, 8 (0–498) | 0, 0 (0–14) | <0.0001e,* | 0.38f |

| Change in lesion volume (µl)g | 9, 192 (−713 to 2031) | 19, 103 (−2238 to 523) | 41, 80 (−2458 to 1816) | 0.68e | >0.99f |

| % change in lesion volumeg | 0.3, 3.6 (−38.9 to 7.7) | 0.5, 1.2 (−14.1 to 4.2) | 0.4, 1 (−9.0 to 2.9) | >0.99e | 0.95f |

| Spinal cord lesions | |||||

| Number of individuals with new lesionsa | 2 (22%) | 2 (6%) | 0 (0%) | 0.10e | 0.54f |

| New lesion numberd | 4, 0, 1 (0–2) | 6, 0, 0 (0–5) | 0, 0, 0 (0–0) | 0.10e | >0.99f |

Active relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis was defined as the presence of a new or enhancing lesion on MRI in the year prior to enrolment in the study.

a n (%).

bChi-square test.

cFisher’s exact test.

dTotal, median, interquartile range (range).

eKruskal–Wallis test.

fMann–Whitney test.

gMedian, interquartile range (range).

hMean ± SD.

*Significant after adjusting for false discovery rate.

Individuals with new cortical lesions did not differ from those with no new cortical lesions with respect to age, sex, disease duration or baseline cortical lesion burden (Table 3). Disease-modifying therapy (categorized as none, injectable, oral, infusion or changed during the study) did not differ between people with new versus no new cortical lesions. Three out of nine people on infusion therapies formed one new cortical lesion each. Two people were on ocrelizumab: one received their first dose ∼1 year before the baseline MRI and the other received their first dose 8 months before the baseline MRI; neither had any interruptions in treatment. One person was on natalizumab for over 1 year before the baseline MRI and did not have any known interruptions in treatment. There was no difference in change in any of the disability measures or in overall disability progression (defined as an increase in EDSS of ≥1.0 for baseline EDSS <6.0 or ≥0.5 for baseline EDSS ≥6.0 or 20% increase in 25FTW or 20% increase in 9HPT) in people with new versus no new cortical lesions (mean clinical follow-up time 2.8 ± 0.7 years).

Table 3.

Characteristics of individuals with new versus stable lesions

| Cortical lesions | White matter lesions | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| New lesions (n = 12) | No new lesions (n = 47) | P-value | New lesions (n = 19) | No new lesions (n = 40) | P-value | |

| Age (years)a | 48 ± 11 | 49 ± 11 | 0.92b | 47 ± 10 | 50 ± 12 | 0.32b |

| Femalec | 10 (83%) | 29 (62%) | 0.19d | 14 (74%) | 25 (63%) | 0.56d |

| Disease duration (years)a | 13 ± 11 | 15 ± 11 | 0.71b | 12 ± 10 | 15 ± 11 | 0.22b |

| Baseline lesions | ||||||

| Cortical lesion numbere | 16, 48 (2–102) | 20, 53 (0–212) | 0.97f | 24, 52 (0–212) | 16, 52 (0–177) | 0.37f |

| Cortical lesion volume (μl)e | 445, 1072 (23–3702) | 384, 2059 (0–9888) | 0.99f | 782, 1960 (0–9888) | 367, 1231 (0–5159) | 0.43f |

| White matter lesion volume (ml)e | 7.2, 11.7 (1.8–32.9) | 8.4, 10.2 (0.9–63.1) | 0.92f | 5.3, 8.5 (1.8–26.5) | 8.5, 14.2 (0.9–62.2) | 0.22f |

| Treatmentc,g | ||||||

| None | 2 (17%) | 4 (9%) | 0.10h | 3 (16%) | 3 (8%) | 0.42h |

| Injectable | 3 (25%) | 5 (11%) | 2 (11%) | 6 (15%) | ||

| Oral | 0 (0%) | 14 (30%) | 4 (21%) | 10 (25%) | ||

| Infusion | 3 (25%) | 6 (13%) | 1 (5%) | 8 (20%) | ||

| Switch | 4 (33%) | 18 (38%) | 9 (47%) | 13 (33%) | ||

| Change in disability | ||||||

| Change in EDSSe | 0, 0.5 (−1.0 to 0.5) | 0, 1.0 (−1.0 to 4.0) | 0.43f | 0, 1.0 (−1.0 to 2.0) | 0, 1.0 (−1.0 to 4.0) | 0.27f |

| 25FTW % changea | 18 ± 38 | 23 ± 51 | 0.75b | 8 ± 18 | 28 ± 56 | 0.11b |

| 9HPT % changea,i | 18 ± 37 | 15 ± 32 | 0.78b | 10 ± 23 | 18 ± 36 | 0.40b |

| PASAT % changea | 5 ± 10 | −1 ± 14 | 0.19b | 2 ± 10 | −1 ± 13 | 0.49b |

| SDMT % changea | −3 ± 13 | 1 ± 17 | 0.50b | 3 ± 20 | −2 ± 13 | 0.37b |

| Overall disability progressionc,j | 3 (25%) | 23 (49%) | 0.20d | 5 (26%) | 22 (55%) | 0.05d |

| Transition from relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis to secondary progressive multiple sclerosisc | 0 (0%) | 5 (15%) | 0.56d | 3 (18%) | 2 (8%) | 0.38d |

25FTW, 25-foot timed walk; 9HPT, 9-hole peg test; EDSS, Expanded Disability Status Scale; PASAT, Paced Auditory Serial Addition Test; SDMT, Symbol Digit Modalities Test.

aMean ± SD.

b t-test.

c n (%).

dFisher’s exact test.

eMedian, interquartile range (range).

fMann–Whitney test.

gInjectable: glatiramer acetate and interferons; oral: dimethyl fumarate, fingolimod and teriflunomide; infusion: daclizumab, natalizumab, ocrelizumab and rituximab.

hChi-square test.

iIn hand with greater worsening.

jOverall disability progression defined as an increase in EDSS of ≥1.0 for baseline EDSS <6.0 or ≥0.5 for baseline EDSS ≥6.0 or 20% increase in 25FTW or 20% increase in 9HPT.

Nineteen individuals formed a total of 96 new white matter lesions, including 9/9 (100%) active relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis, 8/33 (24%) stable relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis and 2/17 (12%) progressive multiple sclerosis (P < 0.0001, stable relapsing-remitting versus progressive multiple sclerosis P = 0.46) (Fig. 1; Table 2). There were no differences in age, sex, disease duration, baseline white matter lesion volume, disease-modifying therapy or change in disability between people with new versus no new white matter lesions. One out of nine people on infusion therapies (ocrelizumab) formed a new white matter lesion; this individual’s first dose of ocrelizumab was 2 months before their baseline MRI. There was no difference in change in any of the disability measures or in overall disability progression in people with new versus no new white matter lesions (Table 3).

Six out of 12 people (50%) with new cortical lesions also formed new white matter lesions, while 13/47 (27%) of people without new cortical lesions formed new white matter lesions (P = 0.17). There was no difference in the subtypes of cortical lesions that formed in people with versus without new white matter lesions (P = 0.69). Three white matter lesions in three individuals expanded into the cortex during the 7T follow-up period. No intracortical or subpial lesions expanded into the white matter.

New spinal cord lesions were rare (10 total new lesions in four individuals) and did not differ between groups (Table 2).

Four individuals had a total of six relapses during the follow-up period. Two individuals were in the active relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis group, and both had new lesions in the white matter, spinal cord and cortex. Two individuals with clinical relapses were in the stable relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis group; neither of these individuals had new lesions in the brain or spinal cord. None of the four had overall disability progression (composite measure of EDSS, 9HPT and 25FTW), and none transitioned from relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis to secondary progressive multiple sclerosis.

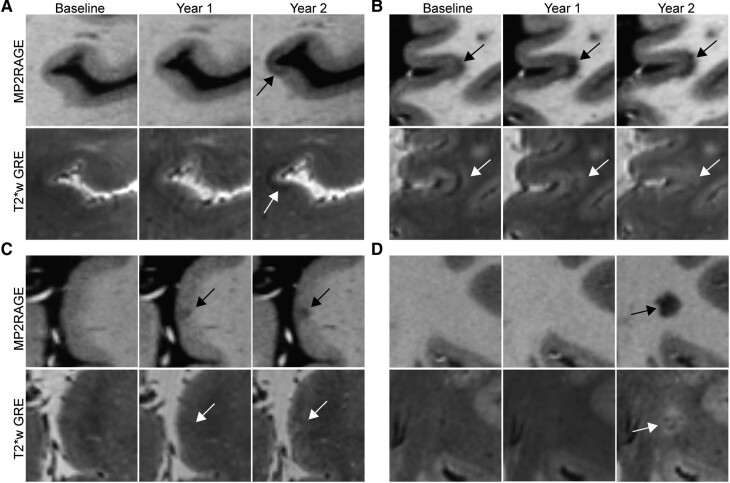

New cortical lesions have a distinct appearance on T2*w images

While most cortical lesions were hypointense on T1w images and hyperintense on T2*w images, we observed that 35% of the new cortical lesions, while hypointense on T1w images, were hypointense or isointense on T2*w images. In contrast, only 10% of new white matter lesions were isointense or hypointense on T2*w images (P = 0.01) (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Appearance of new cortical lesions differs from the appearance of chronic cortical lesions. (A) A subpial lesion that was new on the Year 2 MRI appears hypointense on T2*w GRE. (B) A leukocortical lesion that was present at baseline is initially hyperintense on T2*w GRE with a band of hypointensity at the cortex-white matter junction. This lesion expands over time and becomes more hypointense on T1w MP2RAGE, while at the same time, the hypointense band on T2*w GRE disappears. (C) A subpial lesion that was new on Year 1 MRI initially appears isointense on T2*w GRE and then becomes more hyperintense at Year 2. (D) A white matter lesion in the same individual as (C) was new on Year 2 MRI and is hyperintense on T2*w GRE. Lesions are denoted with arrows. MP2RAGE, magnetization prepared 2 rapid acquisition gradient echo; T2*w GRE, T2*-weighted gradient-recalled echo.

Increase in cortical lesion volume over time is higher in individuals with at least three paramagnetic rim lesions

We examined change in cortical lesion size in two ways: (i) the percentage of lesions that enlarged or shrank over the 7T follow-up period, defined as an increase or decrease in volume of at least 15% respectively, and (ii) absolute and percentage change in total cortical lesion volume, considering only lesions present at baseline.

Of 2365 total cortical lesions present on images from at least two time points, 1963 (83%) were stable in size, 301 (13%) enlarged and 86 (4%) shrank. Leukocortical and intracortical lesions changed in size more frequently (14% of leukocortical lesions enlarged, 7% shrank, 15% of intracortical lesions enlarged and 3% shrank) compared with subpial lesions (12% enlarged and 2% shrank) (P < 0.0001). There was no difference in the percentage of cortical lesions that were enlarging between the active relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis, stable relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis and progressive multiple sclerosis groups (Table 2).

The median change in total cortical lesion volume was 8 µl, IQR 47, range −61 to 215. There was no difference in the absolute or percentage change in total cortical lesion volume between the active relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis, stable relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis and progressive multiple sclerosis groups (Table 2). There was also no difference in white matter lesion volume change between the groups.

We compared change in cortical and white matter lesion volume between individuals with less than three paramagnetic rim lesions (n = 21) and individuals with at least three paramagnetic rim lesions (n = 25) on the baseline 7T scan. There was no difference in change in white matter lesion volume between the two groups (median 14 µl, IQR 42, range −134 to 1816 versus median 43 µl, IQR 173, range −2238 to 2031, P = 0.08). Change in total cortical lesion volume (median 1 µl, IQR 21, range −24 to 184 versus median 16 µl, IQR 64, range −61 to 215, P = 0.007) and change in subpial lesion volume (median 6 µl, IQR 21, range −4 to 176 versus median 23 µl, IQR 37, range −4 to 184, P = 0.02) were higher in the group with at least three paramagnetic rim lesions (Supplementary Table 2).

Baseline cortical lesion burden is associated with worsening disability over time

To determine the association between baseline cortical lesion burden and subsequent change in disability, we considered all available time points at which there was clinical follow-up. Mean clinical follow-up time was 2.8 ± 0.7 years. There was no difference in clinical follow-up time between active relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis, stable relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis and progressive multiple sclerosis (P = 0.07).

Baseline total cortical lesion volume was correlated with percent change in 9HPT (r = 0.69, P < 0.001, adjusted for age and sex, significant after adjusting for multiple comparisons) and 25FTW (r = 0.49, P < 0.001). Baseline leukocortical, intracortical and subpial lesion volume were each associated with percent change in 9HPT and percent change in 25FTW. Baseline cortical lesion volume was not correlated with change in EDSS, PASAT or SDMT. Baseline white matter lesion volume was correlated with percent change in 25FTW (r = 0.45, P < 0.001) and PASAT (r = −0.38, P < 0.01). Baseline normalized brain volume was associated with change in PASAT (r = 0.46, P < 0.01) but not with changes in other disability measures. Baseline spinal cord lesion number was not correlated with change in any of the individual disability measures (Table 4).

Table 4.

Association between baseline MRI measures and longitudinal change in disability

| Change in EDSS | % change 25FTW | % change 9HPTa | % change PASAT | % change SDMT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total cortical lesion number | −0.015 | 0.516b,*** | 0.639b,*** | −0.038 | −0.014 |

| Total cortical lesion volume | 0.020 | 0.488b,*** | 0.686b,*** | −0.130 | −0.050 |

| Leukocortical lesion number | −0.100 | 0.436b,*** | 0.437b,*** | −0.302b,* | −0.009 |

| Leukocortical lesion volume | 0.028 | 0.516b,*** | 0.461b,*** | −0.372b,* | 0.049 |

| Intracortical lesion number | 0.017 | 0.310b,* | 0.508b,*** | 0.000 | −0.225 |

| Intracortical lesion volume | 0.044 | 0.270b,* | 0.540b,*** | −0.038 | −0.235 |

| Subpial lesion number | 0.011 | 0.505b,*** | 0.636b,*** | 0.104 | −0.015 |

| Subpial lesion volume | 0.023 | 0.416b,** | 0.651b,*** | 0.049 | −0.093 |

| White matter lesion volume | −0.099 | 0.450b,*** | 0.123 | −0.382b,** | −0.031 |

| Spinal cord lesion number | −0.003 | 0.121 | 0.100 | −0.109 | 0.207 |

| Normalized brain volume | −0.065 | −0.122 | 0.285 | 0.456b,* | −0.057 |

| Normalized deep grey matter volume | −0.160 | −0.355b,* | −0.122 | 0.408b,* | −0.190 |

| Normalized cortical volume | 0.114 | 0.246 | 0.455b,* | 0.281 | 0.001 |

| Normalized white matter volume | 0.092 | −0.156 | 0.189 | 0.438b,* | 0.080 |

EDSS: Expanded Disability Status Scale.

25FTW: 25-foot timed walk.

9HPT: 9-hole peg test.

PASAT: Paced Auditory Serial Addition Test.

SDMT: Symbol Digit Modalities Test.

aIn hand with greater worsening. Partial correlations, adjusted for age and sex.

bSignificant after adjusting for false discovery rate.

* P < 0.05.

** P < 0.01.

*** P < 0.001.

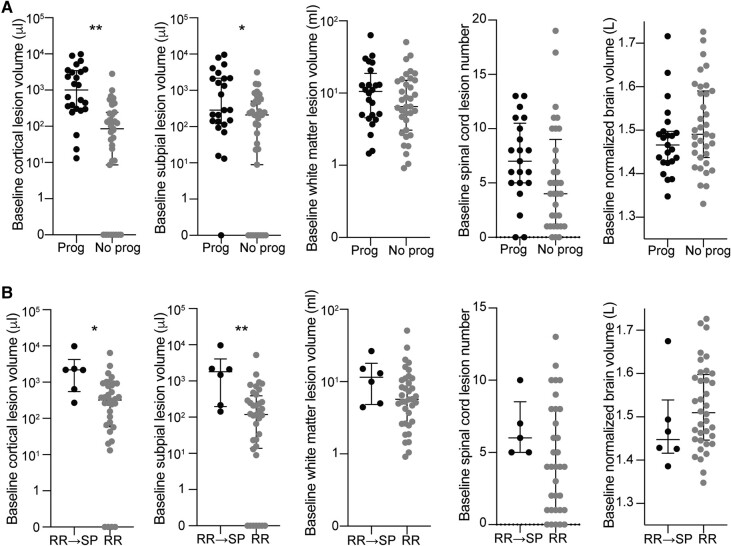

We also determined whether baseline lesion burden was associated with overall progression of disability, defined as an increase in EDSS of ≥1.0 for baseline EDSS <6.0 or ≥0.5 for baseline EDSS ≥6.0 or 20% increase in 25FTW or 20% increase in 9HPT. Baseline cortical lesion volume was higher in people with subsequent progression of disability (median 1010 µl, IQR 3162, range 13–9888) than in those without (median 267 µl, IQR 854, range 0–3539, B 0.809, P = 0.001, adjusted for age and sex) (Fig. 3; Table 5). Baseline volume was also higher in people with progression disability for each of the cortical lesion subtypes. In contrast, baseline white matter lesion volume did not differ between people with subsequent progression of disability (median 10.4 ml, IQR 14.2, range 1.5–63.1) versus those without (median 6.5 ml, IQR 12.0, range 0.9–50.8, B 0.206, P = 0.42). There was also no difference in baseline spinal cord lesion number or baseline normalized brain volume between people with progression of disability versus those without (Fig. 3; Table 5).

Figure 3.

People with worsening disability and transition from relapsing to progressive multiple sclerosis have higher cortical lesion burden at baseline. (A) Individuals with progression of disability during the study (‘Prog’, defined as an increase in EDSS of ≥1.0 for baseline EDSS <6.0 or ≥0.5 for baseline EDSS ≥6.0 or 20% increase in 25FTW or 20% increase in 9HPT) had higher baseline cortical lesion volume and subpial lesion volume, but no difference in baseline white matter lesion volume, spinal cord lesion number or normalized brain volume, compared to people without progression of disability (‘No prog’). Similar results were observed when comparing individuals who transitioned from relapsing-remitting to secondary progressive multiple sclerosis with those who remained relapsing-remitting (B). Comparisons were performed using a multivariable general linear model adjusted for age and sex. RR, relapsing-remitting; SP, secondary progressive. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

Table 5.

Baseline MRI measures in people with progression of disability versus stable disability

| Progression of disabilitya | No progression of disability | B b | P-valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years)c | 50 ± 9 | 48 ± 13 | - | 0.43 |

| Cortical lesionsd | ||||

| Total cortical lesion number | 32, 87 (2–212) | 14, 24 (0–142) | 0.673 | 0.008* |

| Total cortical lesion volume (µl) | 1010, 3162 (13–9888) | 267, 854 (0–3539) | 0.809 | 0.001* |

| Leukocortical lesion number | 12, 26 (0–49) | 5, 12 (0–67) | 0.454 | 0.07 |

| Leukocortical lesion volume (µl) | 262, 921 (0–1709) | 85, 236 (0–2818) | 0.591 | 0.02* |

| Intracortical lesion number | 2, 6 (0–10) | 1, 3 (0–20) | 0.441 | 0.08 |

| Intracortical lesion volume (µl) | 8, 23 (0–71) | 2, 8 (0–65) | 0.525 | 0.04* |

| Subpial lesion number | 16, 50 (0–168) | 6, 14 (0–114) | 0.702 | 0.006* |

| Subpial lesion volume (µl) | 285, 2038 (0–9660) | 209, 496 (0–3131) | 0.777 | 0.002* |

| White matter lesion volume (ml)c | 10.4, 14.2 (1.5–63.1) | 6.5, 12.0 (0.9–50.8) | 0.206 | 0.42 |

| Spinal cord lesion numberd | 7, 5.5 (0–13) | 4, 8 (0–19) | 0.305 | 0.24 |

| Normalized brain volume (ml)c | ||||

| Whole brain | 1468 ± 45 | 1479 ± 56 | −0.035 | 0.59 |

| Deep grey matter | 67 ± 7 | 69 ± 6 | −0.217 | 0.19 |

| Cortex | 659 ± 16 | 656 ± 24 | 0.343 | 0.13 |

| White matter | 560 ± 26 | 558 ± 31 | 0.091 | 0.97 |

aOverall disability progression defined as an increase in Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) of ≥1.0 for baseline EDSS <6.0 or ≥0.5 for baseline EDSS ≥6.0 or 20% increase in 25 foot timed walk or 20% increase in 9-hole peg test.

bMultivariable general linear model adjusted for age and sex.

cMean ± SD.

dMedian, interquartile range (range).

*Significant after adjusting for false discovery rate.

Change in subpial lesion volume was higher in people with progression of disability (B 0.196, P = 0.003). Change in total cortical lesion volume, percentage of enlarging cortical lesions and change in white matter lesion volume did not differ between people with progression of disability versus those without (Supplementary Table 3). Change in cortical lesion volume, percentage of enlarging cortical lesions and change in white matter lesion volume were not associated with change in individual disability measures (Supplementary Table 4).

Six out of 42 individuals with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis at baseline had transitioned to secondary progressive multiple sclerosis by the time of the final clinical follow-up, as determined clinically by the evaluating neurologist. At baseline, individuals who subsequently transitioned to secondary progressive multiple sclerosis had higher total cortical lesion volume (median 2183 µl, IQR 3673, range 270–9888 versus median 321 µl, IQR 832, range 0–6392, B 0.873, P = 0.01, adjusted for age and sex) and subpial lesion volume (median 1489 µl, IQR 3850, range 143–9660 versus median 119 µl, IQR 372, range 0–5233, B 1.047, P = 0.003) than those who remained relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. There was no difference in leukocortical lesion volume, white matter lesion volume or spinal cord lesion number between those who transitioned from relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis to secondary progressive multiple sclerosis versus those who remained relapsing-remitting, nor did baseline brain volume differ between the groups (Fig. 3; Supplementary Table 5).

Discussion

We characterized cortical lesions longitudinally in a cohort of individuals with multiple sclerosis, most of whom had not formed new white matter lesions in the year prior to enrolment in the study. We found that cortical lesion formation was rare in this population, was not higher in progressive versus relapsing multiple sclerosis and was not associated with worsening of disability over time. Importantly, however, baseline cortical lesion burden, but not white matter or spinal cord lesion burden, was higher in people who had subsequent worsening of motor disability and in people who transitioned from relapsing to secondary progressive multiple sclerosis.

Cortical lesion formation in this study was lower than what has previously been reported,31-33 especially in the participants who had stable white matter lesions prior to enrollment. Also in contrast to prior studies,13,14 we did not find a higher rate of cortical lesion formation in progressive multiple sclerosis. Enrollment in these studies occurred between 2009 and 2019, and participants were on lower efficacy treatments than the participants here, of whom 37/59 (63%) were on oral or infusion disease-modifying therapies. Limited observation has previously demonstrated lower rates of cortical lesion formation in people on disease-modifying therapy.34,35 However, these studies were done using 1.5-T double inversion recovery MRI, which has poor sensitivity for cortical, and in particular subpial, lesions.36 Dedicated prospective studies will be needed to test the effects of modern disease-modifying therapies on cortical lesion formation. It is possible that despite evident differences in mechanisms of cortical and white matter lesion formation within the central nervous system, peripheral immune mediators targeted by disease-modifying therapies may be shared. The lower rate of cortical lesion formation in this cohort could also be due to the purposeful recruitment of individuals with stable white matter lesions, resulting in a cohort that was older (mean 49 years) than in prior studies and for the most part had longstanding disease (mean 14 years). We did not find differences in baseline demographic, clinical or MRI measures in individuals with new versus no new cortical lesions; however, this may be due to the very small number of individuals with new cortical lesions.

We also evaluated change in cortical lesion size over time and found that the majority of cortical lesions were stable over the 2-year follow-up. However, we did find that some lesions increased in size and that overall change in cortical lesion volume, excluding new lesions, was higher in people with at least three paramagnetic rim lesions. Unlike in chronic active white matter lesions, activated microglia/macrophages within chronic cortical lesions are rare.23,37-39 Instead, chronic inflammation in cortical, and in particular subpial, lesions may be related to overlying meningeal inflammation. Our data are consistent with a potential shared mechanism underlying inflammation in chronic active white matter lesions and cortical lesions.

Interestingly, we observed several juxtacortical lesions that expanded into the cortex during the follow-up period, whereas we did not observe any intracortical or subpial lesions expand into the white matter. There are very few published longitudinal studies at high enough resolution to capture lesion expansion, although Sethi et al.13 did observe the expansion of lesions from the cortex into the white matter. It is possible that differences in the cortical and white matter microenvironments may lead to differences in lesion expansion into the cortex versus white matter. Longer follow-up and study of individuals with higher rates of new cortical lesion formation, as lesion growth may be maximal soon after lesion formation, may be required to answer this question.

Our finding that cortical lesion burden predicts disability progression and transition from relapsing to secondary progressive multiple sclerosis is in agreement with prior studies, including at least one prior 7T study.14,32,40,41 The lack of new cortical lesions in this older cohort with longstanding disease, combined with the association between baseline cortical lesion burden and 2-year disability worsening, suggests that, at least in the current era, cortical lesions form early in disease12,42 and then may exert long-term effects on disability.

Despite the consistent finding in cross-sectional studies that cortical lesions are associated with cognitive disability,3,5,6,23,43 we found more consistent correlations of cortical lesion burden with subsequent changes in motor disability than with cognitive disability change. Most prior studies have focused on the relationship between cortical lesions and subsequent physical disability worsening, as measured by EDSS,14,32 and there are very limited prior data on the relationship between cortical lesions and worsening cognitive disability.40 One possible explanation for the lack of correlation between cortical lesions and subsequent change in SDMT or PASAT in this study is that there was relatively little change in performance in these tests over the follow-up period (Table 3). Larger, longer-term studies will be needed to determine whether cortical lesions exert their effect on cognition at the time of lesion formation versus leading to long-term changes in cognition.

One potential limitation of this study is that there were changes to scanner software versions on both the 3- and 7T scanners during the study as well as a switch partway through Year 2 to a motion and B0-corrected version of the T2*w GRE sequence. Because of significant differences in image contrast on 3T MP2RAGE images acquired with different WIP sequences, which we found affected tissue segmentation and brain volume calculations, we used baseline 7T MP2RAGE images for brain volume calculations. For longitudinal cortical lesion assessment, we were careful not to count as ‘new’ any cortical lesion that was clearly seen on the motion-corrected T2*w GRE images but could have been obscured by artefact on images from the earlier time points. This occurred rarely, and we did not observe a difference in new cortical lesion count between time points with versus without motion correction, but it is possible that there was a slight undercounting of new cortical lesions. Limited coverage of the inferior temporal and occipital lobes at all time points may also have limited cortical lesion detection in these regions.

This study is also limited by cohort size, which, although larger than most 7T studies in multiple sclerosis to date, limits our ability to identify factors associated with cortical lesion formation. This is an important question for future studies, as cortical and white matter lesion burden are not well correlated and the factors determining which patients develop cortical versus white matter lesions are unclear.

If confirmed, our results have important implications for clinical care and research. They suggest that it is necessary to stop cortical lesion formation early in the disease and provide some support for the possibility that existing disease-modifying therapies may offer at least partial control. The association we find between cortical lesion burden and subsequent worsening of disability may be useful for prognostication and for selecting participants for clinical trials in progressive multiple sclerosis who are likely to worsen over a relatively short follow-up and might benefit most from treatment.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the staff of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke Neuroimmunology Clinic for the care of and collection of clinical data from the study participants and the staff of the National Institute of Mental Health Functional MRI Facility, Matthew Schindler, Martina Absinta, Hadar Kolb and Maxime Donadieu for help with MRI acquisitions. We thank Siemens for providing access to research pulse sequences. We thank Tianxia Wu for her advice on statistical analyses. This work was supported in part through the computational and data resources and staff expertise provided by Scientific Computing and Data at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and supported by the Clinical and Translational Science Awards (CTSA) grant UL1TR004419 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. The graphical abstract was created using BioRender.

Contributor Information

Erin S Beck, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA; Department of Neurology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY 10029, USA.

W Andrew Mullins, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA.

Jonadab dos Santos Silva, Department of Neurology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY 10029, USA.

Stefano Filippini, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA; Department of Neurosciences, Drug, and Child Health, University of Florence, Florence 50121, Italy.

Prasanna Parvathaneni, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA.

Josefina Maranzano, McConnell Brain Imaging Centre, Department of Neurology and Neurosurgery, Montreal Neurological Institute and Hospital, McGill University, Montreal, QC H3A2B4, Canada; Department of Anatomy, University of Quebec, Trois-Rivieres, QC G9A5H7, Canada.

Mark Morrison, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA.

Daniel J Suto, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA.

Corinne Donnay, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA.

Henry Dieckhaus, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA.

Nicholas J Luciano, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA.

Kanika Sharma, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA.

María Ines Gaitán, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA.

Jiaen Liu, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA; Advanced Imaging Research Center and Department of Radiology, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX 75390, USA.

Jacco A de Zwart, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA.

Peter van Gelderen, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA.

Irene Cortese, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA.

Sridar Narayanan, McConnell Brain Imaging Centre, Department of Neurology and Neurosurgery, Montreal Neurological Institute and Hospital, McGill University, Montreal, QC H3A2B4, Canada.

Jeff H Duyn, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA.

Govind Nair, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA.

Pascal Sati, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA; Department of Neurology, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA 90048, USA.

Daniel S Reich, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at Brain Communications online.

Funding

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institutes of Health. E.S.B. was supported by a Clinician Scientist Development Award and a Career Transition Fellowship Award from the National Multiple Sclerosis Society. J.M. and S.N. were supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

Competing interests

The authors report no competing interests.

Data availability

The authors will make the data available to other investigators for the purpose of replication and re-use upon reasonable request.

References

- 1. Kuhlmann T, Moccia M, Coetzee T, et al. Multiple sclerosis progression: Time for a new mechanism-driven framework. Lancet Neurol. 2023;22(1):78–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Reich DS, Lucchinetti CF, Calabresi PA. Multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(2):169–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Calabrese M, Agosta F, Rinaldi F, et al. Cortical lesions and atrophy associated with cognitive impairment in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Arch Neurol. 2009;66(9):1144–1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Roosendaal SD, Moraal B, Pouwels PJ, et al. Accumulation of cortical lesions in MS: Relation with cognitive impairment. Mult Scler. 2009;15(6):708–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nielsen AS, Kinkel RP, Madigan N, Tinelli E, Benner T, Mainero C. Contribution of cortical lesion subtypes at 7T MRI to physical and cognitive performance in MS. Neurology. 2013;81(7):641–649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Harrison DM, Roy S, Oh J, et al. Association of cortical lesion burden on 7-T magnetic resonance imaging with cognition and disability in multiple sclerosis. JAMA Neurol. 2015;72(9):1004–1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Howell OW, Reeves CA, Nicholas R, et al. Meningeal inflammation is widespread and linked to cortical pathology in multiple sclerosis. Brain. 2011;134(Pt 9):2755–2771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Magliozzi R, Howell OW, Nicholas R, et al. Inflammatory intrathecal profiles and cortical damage in multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 2018;83(4):739–755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Magliozzi R, Howell OW, Reeves C, et al. A gradient of neuronal loss and meningeal inflammation in multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 2010;68(4):477–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bø L, Vedeler CA, Nyland HI, Trapp BD, Mork SJ. Subpial demyelination in the cerebral cortex of multiple sclerosis patients. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2003;62(7):723–732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Brownell B, Hughes JT. The distribution of plaques in the cerebrum in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1962;25:315–320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lucchinetti CF, Popescu BF, Bunyan RF, et al. Inflammatory cortical demyelination in early multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(23):2188–2197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sethi V, Yousry T, Muhlert N, et al. A longitudinal study of cortical grey matter lesion subtypes in relapse-onset multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2016;87(7):750–753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Treaba CA, Granberg TE, Sormani MP, et al. Longitudinal characterization of cortical lesion development and evolution in multiple sclerosis with 7.0-T MRI. Radiology. 2019;291(3):740–749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Liu J, Beck ES, Filippini S, et al. Navigator-guided motion and B0 correction of T2*-weighted magnetic resonance imaging improves multiple sclerosis cortical lesion detection. Invest Radiol. 2021;56(7):409–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Liu J, van Gelderen P, de Zwart JA, Duyn JH. Reducing motion sensitivity in 3D high-resolution T2*-weighted MRI by navigator-based motion and nonlinear magnetic field correction. Neuroimage. 2020;206:116332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Beck ES, Sati P, Sethi V, et al. Improved visualization of cortical lesions in multiple sclerosis using 7T MP2RAGE. Am J Neuroradiol. 2018;39(3):459–466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jenkinson M, Smith S. A global optimisation method for robust affine registration of brain images. Med Image Anal. 2001;5(2):143–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jenkinson M, Bannister P, Brady M, Smith S. Improved optimization for the robust and accurate linear registration and motion correction of brain images. Neuroimage. 2002;17(2):825–841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cox RW. AFNI: Software for analysis and visualization of functional magnetic resonance neuroimages. Comput Biomed Res. 1996;29(3):162–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cox RW, Hyde JS. Software tools for analysis and visualization of fMRI data. NMR Biomed. 1997;10(4–5):171–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Maranzano J, Dadar M, Rudko DA, et al. Comparison of multiple sclerosis cortical lesion types detected by multicontrast 3T and 7T MRI. Am J Neuroradiol. 2019;40(7):1162–1169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Beck ES, Maranzano J, Luciano NJ, et al. Cortical lesion hotspots and association of subpial lesions with disability in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2022;28(9):1351–1363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Absinta M, Sati P, Gaitán MI, et al. Seven-tesla phase imaging of acute multiple sclerosis lesions: A new window into the inflammatory process. Ann Neurol. 2013;74(5):669–678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Avants BB, Epstein CL, Grossman M, Gee JC. Symmetric diffeomorphic image registration with cross-correlation: Evaluating automated labeling of elderly and neurodegenerative brain. Med Image Anal. 2008;12(1):26–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Battaglini M, Jenkinson M, De Stefano N. Evaluating and reducing the impact of white matter lesions on brain volume measurements. Hum Brain Mapp. 2012;33(9):2062–2071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Billot B, Greve DN, Puonti O, et al. SynthSeg: Segmentation of brain MRI scans of any contrast and resolution without retraining. Med Image Anal. 2023;86:102789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chernick MR. Bootstrap methods: A guide for practicioners and researchers. 2 ed. Wiley-Interscience; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Efron B. Bootstrap methods: Another look at the jackknife. Ann Stat. 1979;7(1):1–26. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc Ser B (Methodol). 1995;57(1):289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Calabrese M, Rocca MA, Atzori M, et al. Cortical lesions in primary progressive multiple sclerosis: A 2-year longitudinal MR study. Neurology. 2009;72(15):1330–1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Calabrese M, Rocca MA, Atzori M, et al. A 3-year magnetic resonance imaging study of cortical lesions in relapse-onset multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 2010;67(3):376–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Treaba CA, Conti A, Klawiter EC, et al. Cortical and phase rim lesions on 7 T MRI as markers of multiple sclerosis disease progression. Brain Commun. 2021;3(3):fcab134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rinaldi F, Calabrese M, Seppi D, Puthenparampil M, Perini P, Gallo P. Natalizumab strongly suppresses cortical pathology in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2012;18(12):1760–1767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rinaldi F, Perini P, Atzori M, Favaretto A, Seppi D, Gallo P. Disease-modifying drugs reduce cortical lesion accumulation and atrophy progression in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: Results from a 48-month extension study. Mult Scler Int. 2015;2015:369348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kilsdonk ID, Jonkman LE, Klaver R, et al. Increased cortical grey matter lesion detection in multiple sclerosis with 7 T MRI: A post-mortem verification study. Brain. 2016;139(Pt 5):1472–1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Galbusera R, Bahn E, Weigel M, et al. Characteristics, prevalence, and clinical relevance of juxtacortical paramagnetic rims in patients with multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2024;102(3):e207966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Peterson JW, Bö L, Mörk S, Chang A, Trapp BD. Transected neurites, apoptotic neurons, and reduced inflammation in cortical multiple sclerosis lesions. Ann Neurol. 2001;50(3):389–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Absinta M, Sati P, Schindler M, et al. Persistent 7-tesla phase rim predicts poor outcome in new multiple sclerosis patient lesions. J Clin Invest. 2016;126(7):2597–2609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Calabrese M, Poretto V, Favaretto A, et al. Cortical lesion load associates with progression of disability in multiple sclerosis. Brain. 2012;135(Pt 10):2952–2961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Calabrese M, Romualdi C, Poretto V, et al. The changing clinical course of multiple sclerosis: A matter of gray matter. Ann Neurol. 2013;74(1):76–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Maranzano J, Till C, Assemlal HE, et al. Detection and clinical correlation of leukocortical lesions in pediatric-onset multiple sclerosis on multi-contrast MRI. Mult Scler. 2019;25(7):980–986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Nelson F, Datta S, Garcia N, et al. Intracortical lesions by 3T magnetic resonance imaging and correlation with cognitive impairment in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2011;17(9):1122–1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The authors will make the data available to other investigators for the purpose of replication and re-use upon reasonable request.