To mark the 150th anniversary of the 1848 Public Health Act, Iqbal Sram and John Ashton write a memo to Edwin Chadwick, the architect of the 1848 act, on the state of the public health at the end of the millennium

I will not cease from mental strife, Nor shall my sword sleep in my hand Till we have built Jerusalem In England’s green and pleasant land William Blake

Dear Sir Edwin,

We live in a world which you would have envied. You played a dominant role in laying the foundations of this world. A clean and secure water supply for the population at large, coupled with the separate disposal of their sewage and waste, were the central planks of your crusade to protect public health in your day. However, Sir Edwin, we enter a caution here. The harmonious world referred to is, in essence, the “first world.” The insanitary conditions which you were determined to eradicate still persist over large parts of the globe.

It will not have escaped your notice that it is 150 years since the enactment of the 1848 Public Health Act (An Act for promoting the Public Health), for you were its chief architect.1 You subscribed to the contemporary laissez faire doctrines in the management of economic affairs, having worked closely with the economist Nassau Senior in the reform of the poor laws, which dated back to Elizabethan times.2 In the social policy arena you battled hard and successfully against those who wished to extend and entrench that approach to a wide range of public policy areas. Your energy and determination secured support for state intervention for public health protection from the major perceived health hazards of the day,3 in particular the acute infectious diseases. You attributed these to insanitary conditions due to poor and sometimes non-existent drainage and disposal of urban waste and sewage.

It is said that in this context you were mainly concerned with the plight of the ablebodied urban poor. Because you were convinced that many deaths among the urban inhabitants were avoidable,3 you started by identifying the problem and its size and its cause.4 The next stage was to find a workable solution. Here you were greatly assisted by the civil engineers of the day.3 You then proceeded to build support for your evidence based proposals. Although the provisions of the 1848 act fell short of your expectations, its historic significance was clear. The idea that the state can act in an enabling capacity could now be tested.5,6

Summary points

The state has a key role in promoting and protecting public health

Public health today faces a number of challenges posed by globalisation and must develop appropriate responses

Public health should focus on promoting sustainable economic and social development of individuals and communities

Urgent action should be taken in the short term to narrow the health inequalities; priority should be given to measures to raise low incomes

An independent public health commission should be established to monitor the effects of public policies on health and to offer proactive and independent advice on public health to government and other public bodies

Monumental legacy

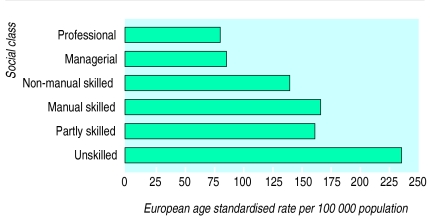

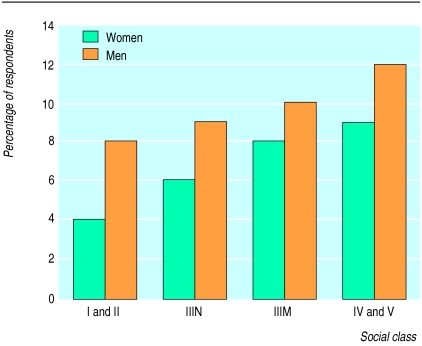

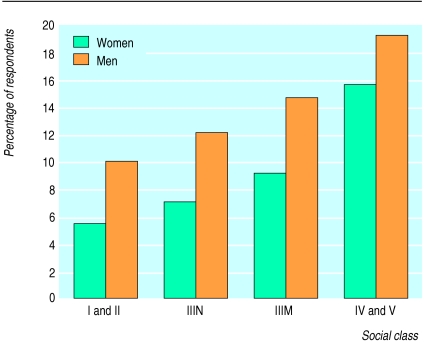

Sir Edwin, your legacy is monumental. Your claim that the major threats to human health originate from the environment now enjoys widespread professional and popular support. Although the world and the public health challenges have changed since 1848, the foundations that you laid continue to guide today’s practitioners. It is disappointing to report that in spite of your leadership, we still have disproportionate levels of ill health in our cities.7 Like the towns in your day, our cities are hazardous places in which to live. Inequalities in health experience and outcomes persist and are associated with avoidable deaths.8 In the 1990s nearly 90 000 people die each year before they reach their 65th birthday. Of these, more than 25 000 die of heart disease, stroke, and related illnesses and 32 000 die of cancer (fig 1).9 Differences in health associated with social class exist not only for mortality but also for morbidity (figs 2, 3).9 In your day, Sir Edwin, the excess deaths occurred mainly among the labouring classes in the towns. Today these chiefly occur among social classes IV and V—the partly skilled and unskilled occupations—of the registrar general’s classification system. (You are of course familiar with this system as you had many interesting debates with its designer, William Farr.11)

Figure 1.

Mortality from coronary heart disease in men aged 20-64, England and Wales 1991-310

Figure 2.

Population survey of diastolic blood pressure >95 mm Hg, England, 199112

Figure 3.

People aged 40-65 with forced expiratory volume more than 2 SD below predicted value, Great Britain13

You must be wondering if there are any modern day policy and structural innovations that might be deployed to meet today’s public health challenges. The current government’s public health strategy is outlined in the green paper Our Healthier Nation.9 The green paper’s focus on the environment as a key factor associated with health would have appealed to you.

Factors affecting health (as given in Our Healthier Nation9)

| Fixed: | |

| •Genes | Lifestyle: |

| • Sex | |

| • Ageing | |

| Social and economic: | |

| •Poverty | |

| • Employment | |

| • Social exclusion | |

| Environment: | |

| •Air quality | |

| • Housing | |

| • Water quality | |

| • Social environment |

Diet

Physical activity

Smoking

Alcohol

Sexual behaviour

Drugs

Access to services:

Education

NHS

Social services

Transport

Leisure

The current holistic model of the environment, with its insistence that attention be directed at economic and social dimensions, in addition to the physical factors of your day, enables us to make public health policy more relevant to the population’s health.14 The model obliges public health professionals to allow and enable the population to participate in key decisions relevant to their health and in addition encourages empowerment of the population. The role of professionals in public affairs,5 to which you attached great importance, is maintained, but in a more democratic form.

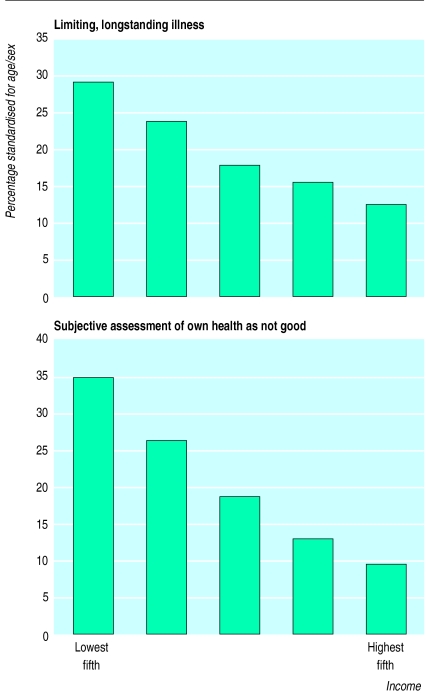

Income inequalities

It is well known that you were not persuaded that low income or no income was an important determinant of health.15 However, the current evidence points to a strong association between low income and ill health (fig 4).16 The shareout of work and reward from paid work among the population is uneven, with some sections experiencing work related stress due to excessive working hours while others are excluded from the labour market, hence from society.18 Income inequality grew greatly in the 1980s in Britain, largely because of discretionary changes to the tax and benefit system.18 The major change has been a switch from taxes on income to taxes on spending. These tax changes are regressive in that they impose a larger tax burden on low income families.19 You would have noted that these changes are the outcome of legislative intervention and not due to the operation of Adam Smith’s invisible hand.8,19

Figure 4.

Limiting, longstanding illness (top) and subjective assessment of own health as not good (bottom) in Great Britain divided into fifths of income17

Low income, however it is defined, has been attributed to unemployment, lone parenthood, low wages combined with high outgoings, and self employment.20,21 Various policy options have been proposed to dislodge the observed income inequalities. A useful distinction is drawn between measures to tackle the causes of low income and its consequences.8 Thus some writers feel that the most effective way to reduce poverty associated with low income is to create more employment opportunities in the economy.22,23 These writers have concentrated on the supply side of the national economy and have proposed measures to enhance the job prospects of those seeking paid employment: improving the skills of those who are unemployed through education and training. It should be added that the case for active management of demand in the economy is being made by a number of eminent economists.24,25 The current government’s “new deal” programme is an attempt to improve the supply side economic variables.26 The expectation is that this will improve the employability of the unemployed sections of the population. Other writers have proposed measures that would reduce the “disincentives” of taking up paid employment at the low wage end of the labour market.8 The proponents of these measures argue that at the very least they will arrest the widening of income related health inequalities.

The current evidence suggests that there would be 42 000 fewer deaths each year in England and Wales for people aged 16-74 if the death rates of people with manual jobs were the same as those for people with non-manual occupations.27 It is also estimated that if the whole population experienced the same death rate as the non-manual classes there would be 700 fewer stillbirths and 1500 fewer deaths in the first year of life in England and Wales.28

These particular health inequalities are unlikely to be reduced unless the incomes of those at the lower end of the population income distribution curve are raised.8 However, some other measures to accelerate this process have also been proposed.29 These fall into four areas: strengthening individuals, strengthening communities, improving access to essential facilities and services, and encouraging macroeconomic and cultural change (box).

Measures to reduce income inequality

Strengthening individuals:

Stress management

Smoking cessation

Counselling for people who become unemployed

Strengthening communities30:

Social control of illegal activity

Socialisation of the young as participating members of the community

Providing first employment

Improving access to formal and informal health care

Social support for health maintenance

Allowing the exercise of political power to direct resources to that community

Limiting duration and intensity of experimentation with dangerous and destructive activity

Improving access to essential facilities and services:

Needs based and driven provision

Make equity the determining factor for provision

Remove financial and geographical barriers to access and uptake

Encouraging macroeconomic and cultural change:

Reduce income differentials at population level

Sustain high levels of employment

Improve working conditions

Create conditions for social cohesion and stability

The case for the widespread use of these measures as instruments of public policy to reduce health inequalities is compelling.8 We feel that the lawyer in you would strongly say that the burden of proof is on those who feel that inaction or a different course of action here is the most appropriate policy stance.

Housing and environment

Sir Edwin, you would be disappointed to learn that today about 4.5 million people in England alone live in houses which are unfit for habitation by statutory standards.31 On balance these figures are likely to understate the magnitude of the problem. Forty per cent of all fatal accidents in Britain occur in the home. Home related accidents are the most common cause of death in children over 1 year, and almost half of all accidental deaths in the home are due to architectural features in and around the home.32 People living in high rise buildings are more prone to serious accidents, such as falling from windows and balconies.33 The industrial building techniques of the 1960s and the 1970s have left a legacy that is likely to cause problems for years to come. The buildings of this type are particularly prone to infestation by cockroaches.34 Although statistics are less helpful in establishing a clear link between housing and stress related illness, there are good grounds for believing that poor sound insulation between neighbouring homes, a lack of privacy, and overcrowding can all contribute to mental health problems.35 In your day you made use of the skills of talented civil engineers and design engineers to help you meet the public health challenges you set yourself.1 You will be pleased to learn that we are beginning to turn to our architects and builders to help us address these problems.36 We suspect that more could be done in this area.

The green paper leaves no doubt that the major determinants of health today are, as ever, environmental. The biomedical model of disease causation has distorted public health priorities in recent years. Its limitations were apparent to you, although the Lancet and Royal College of Physicians strongly disagreed with your analysis at the time.3 However, your preference for the environmental model created some difficulties for you. The main one was that the necessary public health capability and capacity were lacking at the time to give effect to your model and plans. Your energy was therefore directed to improving the then deficient capacity and capability.

You will not be surprised to learn that we are still preoccupied with the issues of public health capacity and capability. The present public health challenge is to operate effectively in an arena dominated by large corporations that function at the supranational level. The labour markets show unstable tendencies. Structural and other changes in these two areas can have profound implications for public health. Furthermore, as discussed in a recent workshop on a future public health act, a number of health hazards today have international dimensions. Modern national environments thus can be influenced by acts or omissions of various actors whose actions and motives cannot always be predicated with ease or accuracy. These changes require the public health response to be timely, multidimensional, and multilateral—and frequently international. Sir Edwin, your example of driving through change and of being able to create new tailormade structures in difficult circumstances to manage this change is comforting in that it inspires us to face today’s challenges with confidence and optimism.5

Another anniversary

This year, 1998, also marks another significant anniversary, the 50th anniversary of the National Health Service. The NHS and the rest of the modern welfare state, which evolved and developed from some of the structures you helped set up, were given their present rationale and coherence by Sir William Beveridge. Beveridge directed his attack at five social evils—want, ignorance, idleness, squalor, and disease.37 While these still pose problems, there is a growing consensus that a public health strategy based on the Beveridge parameters cannot be the route map for the next millennium The current feeling is that the core theme of the new agenda should aim to promote the sustainable economic and social development of communities and individuals. The dividends would be the improvement of social capital, resulting in improved individual and collective safety, security, and quality of life.38

Legal measures

Sir Edwin, since the 1848 act many legislative measures have been enacted to protect public health. Indeed there are at least 50 acts of parliament which directly relate to public health.39–42 The enormous number of statutory instruments is further evidence of legislative intervention in the public health field. A legal source with potential public health implications which did not exist in your day is European Union law. The legal basis of the union’s current competence in public health issues is to be found in articles 3 (0) and 129 of the Treaty of Maastricht as amended by article 152 of the Treaty of Amsterdam.43

Several other bodies with public health related functions have been created in recent years. The main ones are the Health and Safety Commission, the Environment Agency and the (to be enacted) Food Standards Agency. In addition, the statutory regulation of other areas of socioeconomic life enhance public health protection—examples are consumer protection legislation and road traffic legislation. Although the effectiveness of these measures in protecting public health has not been systematically evaluated, they seem to be essential in establishing and maintaining the minimum standards for environmental and public safety.44 There is a view that public health legislation should be rationalised in the shape of a new public health act. However, given the multifaceted nature of public health and a large number of potential actors, agents, and institutions with a legitimate interest in public health it would be difficult to create a single body for this task. A better way to procure a pivotal role for public health would be to ensure that the public health resources and values are located within the various bodies (at various tiers) that are responsible for public health. This option is likely to require an increase in public health capacity and an improved capability. The chief medical officer’s recent review of the public health function provides an opportunity for movement on this front.45

Since your time the role of the state in public affairs has grown in spite of the desire of many with power and the motives to reduce the size and scope of this role.46 The state has the power to influence and sometimes determine the social and economic circumstances of the day.19,25 These can have a great bearing on public health. Public health thus needs protection from acts or omissions of government and non-government bodies. The current arrangements for public health protection have sometimes been found to be wanting.

Complex structures

Sir Edwin, it is well known that you were no respecter of tradition, particularly if it prevented effective action. Your great motto was that structure should follow function.47 We feel that many public health problems which emerge today are complex. They tend to get into the public domain very quickly, and they often require a swift but well considered response. We therefore propose that the government give serious consideration to the setting up of a standing body, independent of government, which would among other things advise it on all issues concerning public health in the United Kingdom. In addition, we propose that this body be charged with the duty to evaluate the public health implications of the policies and actions of all major public bodies (including central government). In this call we enjoy widespread support. We aim to win support for a standing and independent public health commission, as its time has come. The proposed commission would resemble your General Board of Health3 in some ways, the fundamental difference being its complete independence of the state.

Sir Edwin, your courage and energy helped give the public health movement the firm foundations that have enabled it successfully to negotiate many difficult hurdles. We thank you for an inestimable legacy. What you started has to continue, for social reform is a process, not an event.

Acknowledgments

Participants in the NHS Executive North West’s workshop on a future public health act, held in London in May 1998, were Maggi Morris, Gabriel Scally, Sally Sheard, Maria Duggan, Steven Watkins, John Ashton, Richard Smith, Clara Mackay, Naomi Fulop, John Pickstone, David Hunter, Howard Price, John Carrier, Martin Carraher, Rona Cruickshank, John Murray, Swapna Prabu, and Iqbal Sram.

Editorials by Alderslade, PalmerRecent advances p 584Education and debate pp 587, 596

References

- 1.Finer SE. The life and times of Sir Edwin Chadwick. London: Methuen; 1952. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Royle E. Modern Britain: a social history 1750-1997. 2nd ed. London: Arnold; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jones K. The making of social policy in Britain, 1830-1990. 2nd ed. London: Athlone; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Midwinter E. The development of social welfare in Britain. Milton Keynes: Open University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Evans EJ. The forging of the modern state: early industrial Britain 1783-1870. 2nd ed. London: Longman; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hamlin C, Sheard S. Revolutions in public health: 1848, and 1998? BMJ. 1998;317:587–591. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7158.587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ashton J, Knight L, editors. Liverpool: University of Liverpool, Department of Public Health; 1988. Proceedings of the first United Kingdom healthy cities conference, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benzeval M, Judge K, Whitehead M. Tackling inequalities in health: an agenda for action. London: King’s Fund; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Our healthier nation: a contract for health. London: Stationery Office; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Denver F, Whitehead M. London: Office for National Statistics; 1997. Health inequalities. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hamlin C. Could you starve to death in England in 1839?. The Chadwick-Farr controversy and the loss of the “social” in public health. Am J Public Health. 1995;85:856–865. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.6.856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.White A, Nicolaas K, Foster F, Browne F, Carey S. Health survey for England 1991. London: HMSO; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cox M, et al. The health and lifestyle survey: preliminary report of a nationwide survey of the physical and mental health, attitudes and lifestyle of a random sample of 9,003 British adults. London: Health Promotion Trust; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ashton JR, Seymour H. The new public health. Milton Keynes: Open University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hamlin C. Public health and social justice in the age of Chadwick: Britain 1800-1854. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilkinson RG. Unhealthy societies: the afflictions of inequalities. London: Routledge; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 17.O’Donnell O, Propper C. Equity and distribution of UK health services. J Health Econ. 1991;10:1–19. doi: 10.1016/0167-6296(91)90014-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blane D, Brunner E, Wilkinson RG. Health and social organisation: towards a health policy for the 21st century. London: Routledge; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Michie J. The economic legacy, 1979-1992. London: Academic Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson P, Webb S. Explaining the growth in UK income inequality 1979-1988. Economic Journal Conference Papers. 1993;103(suppl 417):429–435. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Webb S, Wilcox J. Time for mortgage benefits. York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leadbeater C, Mullgan G. The end of employment bringing work to life. Demos 1994;No 2:4-14.

- 23.Skidelsky R, Halligan L. Beyond unemployment. London: Social Market Foundation; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stewart M. Keynes in the 1990s: a return to economic sanity. London: Penguin; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hutton W. The state we are in. London: Vintage; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Department for Education and Employment. London: Department of Education and Employment; 1998. Work ethic boost as new deal goes live. (Press release 17/04/98 dated 06/04/1998.) [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jacobson B, Smith A, Whitehead M. The nation’s health: a strategy for the 1990s. London: King’s Fund; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Delamothe T. Social inequalities in health. BMJ. 1991;303:1046–1050. doi: 10.1136/bmj.303.6809.1046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dahlgren G, Whitehead M. Policies and strategies to promote social equity in health. Copenhagen: World Health Organisation; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Department of Health. Healthy living centres. London: Department of Health; 1997. (MISC(97)83.) [Google Scholar]

- 31.Department of Environment. English house condition survey, 1991. London: HMSO; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Department of Trade and Industry. Home and leisure accident research: twelfth annual report. 1988 data. London: DTI Consumer Safety Unit; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Child Accident Prevention Trust. Basic principles of child accident prevention. London: CAPT; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Freeman H. Mental health and high rising housing. In: Burridge R, Ormandy D, editors. Unhealthy housing: research, remedies and reform. London: Spon; 1993. pp. 168–190. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gabe J, Williams P. Women, crowding and mental health. In: Burridge R, Ormandy D, editors. Unhealthy housing: research, remedies and reform. London: Spon; 1993. pp. 191–208. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gibson T. Meadowell community development. Telford: Neighbourhood Initiatives Foundation; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Timmins N. The five giants: a biography of the welfare state. London: Fontana; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Commission for Social Justice. Social justice; strategies for national renewal: the report of the Commission for Social Justice. London: Vintage; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Halsbury’s laws of England. 4th ed. Vol. 38. London: Butterworths; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Halsbury’s laws of England, annual abridgement. 4th ed. London: Butterworths; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Halsbury’s statutes. 4th ed. Vol. 35. London: Butterworths; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Halsbury’s statutes, current status service. 4th ed. London: Butterworths; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mossialos E, McKee M. The Treaty of Amsterdam and the future of European health services. J Health Serv Res Policy 1998;3(April):2. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Bell S. Environmental law. 4th ed. London: Blackwell Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Department of Health. Chief medical officer’s project to strengthen the public health function in England: a report of emerging findings. London: Department of Health; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kavanagh D. Thatcherism and British politics: the end of consensus? Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ashton JR. Is a healthy north west region achievable in the 21st century? J Epidemiol Community Health (in press). (Chadwick lecture 1997.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]