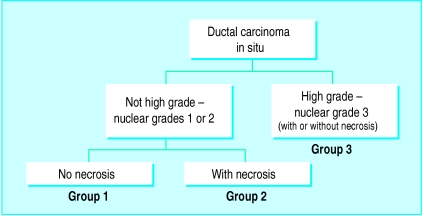

Ductal carcinoma in situ is a proliferation of malignant epithelial cells within the ductolobular system of the breast that show no light microscopic evidence of invasion through the basement membrane into the surrounding stroma (fig 1). Several forms of histological architecture are recognised, the most common of which are comedo, cribriform, solid, micropapillary, and papillary.

Figure 1.

Ductal carcinoma in situ: two histological forms—micropapillary (left) and comedo-type (right)—are evident

Until recently, ductal carcinoma in situ was a relatively uncommon disease, representing only about 1% of all newly diagnosed cases of breast cancer.1 It was usually regarded as a single disease with a single treatment, namely, mastectomy. Most patients presenting with ductal carcinoma in situ had symptoms—a palpable mass or discharge from the nipple. During the past decade, as mammography has become more widely used and technically better, the number of new cases has increased dramatically. Most patients now present with lesions that are not palpable and are clinically occult. Furthermore, the notion of ductal carcinoma in situ as a single disease has evaporated. It is now well recognised as a heterogeneous group of lesions with a diverse malignant potential. As our understanding of the disease has evolved and the range of treatment options has widened, the process of making decisions about management has become more complex and controversial. Ductal carcinoma in situ has become so common and so confusing that the first textbook devoted solely to the disorder was not published until 1997.2

Summary points

Cases of ductal carcinoma in situ have increased appreciably as mammography has improved and pathologists are becoming more familiar with minimal lesions

Ductal carcinoma in situ is a heterogeneous group of lesions, and no single approach to treatment is suitable for all patients

Although radiotherapy is recommended after lumpectomy, this may not be necessary in all subgroups of patients

The Van Nuys prognostic index combines scores for three prognostic factors; it ranges from 3 (best prognosis) to 9 (worst prognosis) and may be useful in planning treatment

Width of the excision margin around the tumour remains the most important factor in prognosis

Rates for mortality and risk of invasive recurrence at eight years are 1.4% and 7% respectively

Methods

For this review I selected articles according to their scientific and clinical importance, but I drew heavily on my 19 years’ experience at a centre that has had considerable experience in treating patients with ductal carcinoma in situ.

Diagnosis

During 1997, more than 36 000 new cases of ductal carcinoma in situ, representing 17% of all new breast cancers, were diagnosed in the United States.3 Most of these cases were diagnosed by mammography. High quality mammography is capable of finding a range of asymptomatic non-invasive lesions that cannot be palpated. These are often smaller, of lower nuclear grade, and show much subtler changes than the lesions detected with less advanced mammographic equipment in the past.

Technically good mammography requires exceptional attention to detail. The need for expert radiological interpretation cannot be overemphasised. The most common mammographic finding is microcalcifications, but some lesions may present as masses or architectural distortions with or without microcalcifications.

The considerable effect of modern mammography can be appreciated by analysing the method of detecting ductal carcinoma in situ at the Breast Center in Van Nuys. During the first three years of operation (1979-81), with only a single outdated mammography unit available and no full time radiologist, an average of five cases was found each year, only 16% of which were non-palpable and were detected mammographically. Beginning in 1982, four new state of the art mammography units were added, along with a full time radiologist specialising in mammography. The number of new cases increased dramatically. In the past five years, 92% of all newly diagnosed patients with ductal carcinoma in situ had non-palpable lesions found mammographically.4 Fifty eight cases were diagnosed in 1997, 11 times the number found in our first year of operation.

Classification

In April 1997, a consensus conference on the pathology of ductal carcinoma in situ was convened in Philadelphia under the auspices of the Breast Health Institute. Although there was agreement on a number of basic issues, such as the need to achieve sufficiently wide excision margins, measure tumour extent, and note nuclear grade, histological architecture, and polarisation, consensus on a single unified classification for ductal carcinoma in situ was not achieved.5

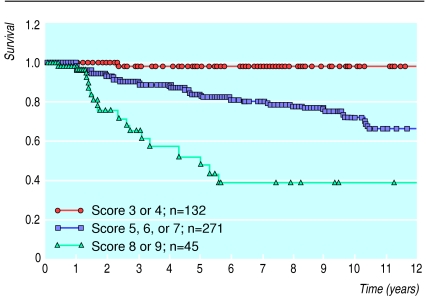

At present there are several classifications based on histological structure, nuclear grade, comedo-type necrosis, cytonuclear differentiation, or various combinations of these factors. Nuclear grade, comedo-type necrosis, tumour size, and the width of the tumour margin are all important predictors of the probability of local recurrence after breast conservation treatment for ductal carcinoma in situ.6–13 Two of these factors, nuclear grade and necrosis, were used to develop a simple, reproducible classification called the Van Nuys classification (fig 2).7,14 This classification yields three different subgroups of patients with ductal carcinoma in situ, with different rates of local recurrence after breast conservation.7 But histological classification alone, no matter which one is used, is inadequate for determining proper treatment. A small, aggressive looking lesion may be adequately treated by excision alone if the margins are widely clear, whereas a large, seemingly unaggressive lesion with an excision margin that is not clear may be better treated by mastectomy and immediate reconstruction. Clearly, factors in addition to the morphological appearance must be considered when planning treatment.8,12

Figure 2.

Van Nuys pathological classification for ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. Reprinted with permission7

Treatment

For years, the standard treatment for most patients with ductal carcinoma in situ has been mastectomy. Although mastectomy is clearly overtreatment for many cases, it results in an extremely low local recurrence rate and mortality from breast cancer.1,6 In the past decade, interest in breast conserving surgery for patients with ductal carcinoma in situ has been considerable. A number of prospective randomised trials evaluating breast preservation are in progress in Europe, including the European organisation for research and treatment of cancer trial and the UK trial (which includes a tamoxifen arm). Both of these trials are approaching a stage at which data will be available. To date, however, only one prospective randomised trial has been published. This is protocol B-17, performed by the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast Project in the United States.15

Protocol B-17

The results of protocol B-17 were updated in 1995 and 1998.13,16 In this study, more than 800 patients with ductal carcinoma in situ that had been excised with clear surgical margins were randomised to two groups—treatment with excision only and excision plus radiotherapy. After eight years of follow up, a significant decrease in local recurrence of ductal carcinoma in situ and invasive breast cancer was seen in patients treated with radiotherapy. The overall local recurrence rate for patients treated by excision only was 27% at eight years. For patients treated with excision plus irradiation, it was 12% at eight years.16 Radiotherapy resulted in a significant decrease in non-invasive ductal carcinoma in situ as well as in invasive local recurrence. These data led the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast Project to continue to recommend postoperative radiotherapy for all patients with ductal carcinoma in situ who chose to save their breasts—a recommendation that I consider too broad at this time.

Criticism of the protocol

Protocol B-17 has been criticised for a number of reasons, the most important being a lack of analysis of different pathological subsets and the lack of size measurements in more than 40% of cases in the initial report.17,18 Other problems include the lack of requirement for mammographic-pathological correlation or specimen radiography; no uniform guidelines for tissue processing or size estimation; and the authors’ definition of what constitutes a clear excision margin. The project group defines clear excision margins as a tumour that has not been transected. A few fat cells or collagen fibres between the tumour and the inked margin are all that is required to call the margin clear. If excision margins are defined in this way, some patients who have appreciable residual disease are placed in the group with clear margins.

In defence of the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast Project Group, its trial was designed more than 14 years ago, at a time when researchers were asking a single broad question: Does radiotherapy benefit patients with ductal carcinoma in situ treated with breast preservation? The answer to that question is clearly, yes. However, the study was not designed to answer the more sophisticated questions we ask today of exactly which subgroups might benefit from radiotherapy and by how much. If the benefit in a given subgroup is small, the advantage gained by radiotherapy will probably be more than offset by its cost and disadvantages.

Subgroups and radiotherapy

Radiotherapy is expensive and, in a very few cases, is accompanied by considerable side effects such as cardiac toxicity and pulmonary fibrosis.19 Radiation fibrosis is a more common side effect, particularly with some of the older outmoded radiotherapy techniques common during the 1980s. This complication changes the texture of the breast, makes mammographic follow up more difficult, and may result in delayed diagnosis if there is a recurrence. Doctors must be satisfied that the benefits of radiation, in terms of improved survival free of recurrence, outweigh considerably the side effects, complications, inconvenience, and costs.

Consider the following two patients, both of whom would receive postoperative radiotherapy if treated according to the recommendations of protocol B-17. The first is a woman with a low grade ductal carcinoma in situ of 7 mm that has been widely excised with a minimum of 15 mm margins in all directions. Compare her with the second patient, a woman with a high grade lesion of 17 mm showing comedo-type necrosis in which ductal carcinoma in situ approaches to within 0.3 mm of the inked margin, but does not involve it. According to protocol B-17, both of these patients should be treated with radiotherapy and in neither is further excision recommended. At my centre, the first patient would receive no additional treatment. She would be carefully followed with physical examination and mammography every six months. The second patient would undergo a wide re-excision before a final treatment decision was made. If appreciable residual disease approaching the new margins were found, mastectomy and immediate reconstruction would be recommended; if widely clear new margins with little or no residual ductal carcinoma in situ were found, radiotherapy or perhaps follow up alone would be recommended. The data on which those treatment recommendations are based will be discussed below in the section on the Van Nuys prognostic index.

Current approaches

Current treatments for ductal carcinoma in situ range from simple tumour excision, to various forms of wider excision (segmental resection, quadrant resection), to mastectomy with or without reconstruction. All treatments less than mastectomy may be followed by radiotherapy. Since ductal carcinoma in situ is a heterogeneous group of lesions, and because patients have a variety of personal agendas that must be considered when selecting treatment, no single approach will be appropriate for all forms of the disease. Methods must be developed to determine the best treatment for each patient.

If untreated, the most innocuous looking forms of ductal carcinoma in situ (for example, those of low nuclear grade, small celled without necrosis, and positive for oestrogen and progesterone receptor, and those that are negative for c-erbB2) may never cause a clinical problem. Only about 40% of untreated low grade lesions become invasive over a time span of approximately 25-30 years.20 This has led both doctors and patients to question whether these lesions should have been classified as cancer in the first place. On the other hand, the most aggressive forms of ductal carcinoma in situ (high nuclear grade, large celled with comedo-type necrosis) are much more likely to develop into invasive carcinomas if left untreated, and in considerably shorter periods of time.

Doctors need to know which lesions, if untreated, are going to become invasive breast cancer. They need to know which lesions, if treated conservatively, have such high rates of recurrence that mastectomy is the preferred treatment. And they need to know which patients in the group who do not need mastectomy can be treated by tumour excision alone and which ones need postoperative radiotherapy. The questions are simple; the answers are not and are the focus of international debate.

The axilla

There is now uniform agreement that for patients with ductal carcinoma in situ, the axilla need not be treated.21,22 In this centre, the axilla is not treated in any fashion in patients with ductal carcinoma in situ undergoing breast conservation surgery. It is not irradiated and no form of axillary sampling or dissection is performed. For patients with lesions large enough to require mastectomy, a sentinel node biopsy is performed using a vital blue dye, a radioactive tracer, or both, at the time of mastectomy.23–25 This is done in case permanent sectioning of the mastectomy specimen shows one or more foci of invasion. If invasion is documented, no matter how tiny, the lesion is no longer considered ductal carcinoma in situ but rather an invasive cancer with an extensive intraductal component. The lesion size is the maximum diameter of the largest invasive focus (not the diameter of the ductal carcinoma in situ). The sentinel node or nodes are evaluated by haematoxylin and eosin staining, and where routine stains are negative, this is followed by immunohistochemical investigation for cytokeratin.

Van Nuys prognostic index

Nuclear grade, the presence of comedo-type necrosis, tumour size, and the width of the excision margin are all important factors capable of predicting local recurrence in patients with ductal carcinoma in situ.6–12 By using a combination of these factors it may be possible to select subgroups of patients who do not require irradiation if breast conservation is chosen or whose recurrence rate is potentially so high, even with breast irradiation, that mastectomy is preferable.

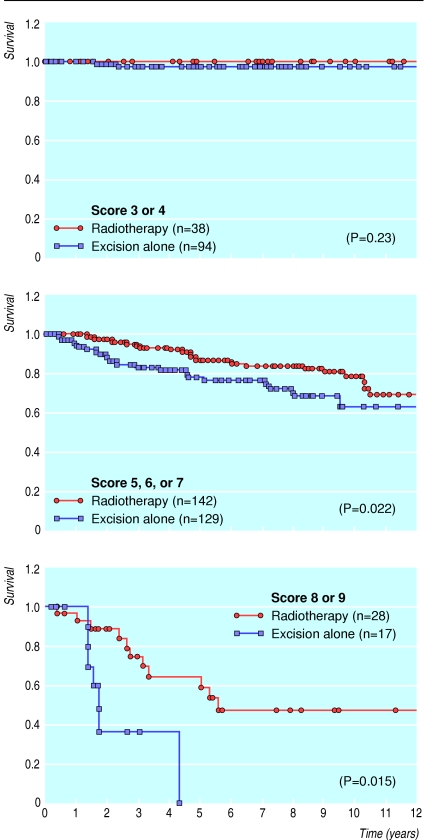

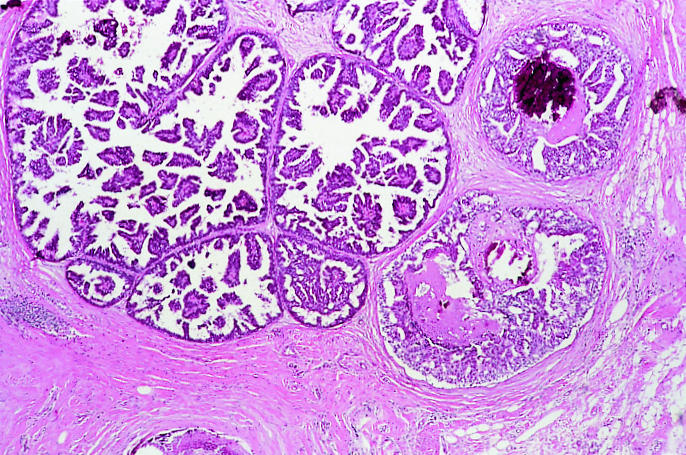

As I have already mentioned, the first two of these prognostic factors, nuclear grade and comedo-type necrosis, were used to develop the Van Nuys pathological classification.7 However, nuclear grade and comedo-type necrosis are inadequate as the sole guidelines in the treatment selection process—tumour size and margin width are also important.12 By combining all of these factors, the Van Nuys prognostic index was developed.8 Scores from 1 to 3 were given for each of the three different predictors of local breast recurrence (size of the tumour, width of the margin, and pathological classification) for a group of 448 patients with ductal carcinoma in situ treated with breast preservation. Table 1 shows the Van Nuys prognostic index scoring system. The scores for each predictor for each individual patient were totalled to yield a score ranging from a low of 3 (best prognosis) to a high of 9 (worst prognosis). Fig 3 shows the probability of recurrence in 448 patients divided into three subgroups on the basis of their score (3 or 4 versus 5, 6, or 7 versus 8 or 9). The probability of local recurrence is significantly different for each subgroup. More importantly, patients with low scores (3 or 4) showed no difference in survival free of local recurrence at 12 years regardless of whether they had had radiotherapy (fig 4). They can therefore be considered for treatment with excision only. Patients with intermediate scores (5, 6, or 7) showed a significant decrease in local recurrence rates with radiotherapy (fig 4). Conservatively treated patients with scores of 8 or 9 had unacceptably high local recurrence rates, regardless of irradiation (fig 4), and should be considered for mastectomy.

Table 1.

Van Nuys prognostic index scoring system*

| Predictor | Score

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Tumour size (mm) | ⩽15 | 16-40 | ⩾41 |

| Margin width (mm) | ⩾10 | 1-9 | <1 |

| Pathological classification | Not high grade, no necrosis (nuclear grades 1 and 2) | Not high grade, with necrosis (nuclear grades 1 and 2) | High grade with or without necrosis (nuclear grade 3) |

Scores (1-3) for each of the predictors are totalled to yield an index score ranging from a low of 3 to a high of 9. Reproduced with permission8

Figure 3.

Probability of survival free of local recurrence for 448 patients treated by breast conservation surgery in relation to their Van Nuys prognostic index score (3 or 4 v 5, 6, or 7 v 8 or 9)

Figure 4.

Probability of survival free of local recurrence after breast conservation surgery with and without radiotherapy in patients with Van Nuys prognostic index scores of 3 or 4; 5, 6, or 7; or 8 or 9

The Van Nuys prognostic index is a numerical algorithm based on tumour features (which cannot be controlled by the patient or surgeon) and recurrence data from a large series of patients with ductal carcinoma in situ. It allows us to quantify prognostic factors that are easily measured and to place patients into one of three clearly defined risk groups. Formulation of the score is designed to be within the capabilities of any hospital. The index allows a more rational approach to the treatment of ductal carcinoma in situ, which at present is often based on anecdotal experience. The prognostic index was designed to be used in conjunction with, and not instead of, clinical experience and prospective randomised data. As with all these aids to treatment planning, it will need to be validated independently.

Margin width

Margin width—the distance between ductal carcinoma in situ and the closest inked margin—reflects the completeness of excision. Although the multivariate analysis used to derive the Van Nuys prognostic index suggests approximately equal importance for the three major factors (margin width, tumour size, and classification), the width of the margin should indeed be the single most important factor. In other words, since ductal carcinoma in situ is a non-invasive lesion without the ability to invade and metastasise (two critically important components of the fully expressed malignant phenotype), complete excision should produce a cure. Currently, the best way to assess complete excision is by determining margin width. The work of Holland and Faverly suggests that when margin widths exceed 10 mm, the likelihood of residual disease is relatively small.26 Data from the Breast Center in Van Nuys show that there is little benefit from radiotherapy after excision of the carcinoma if margins are greater than 10 mm, regardless of the nuclear grade27 or the presence of comedo-type necrosis.28

The value of margin width has been confirmed by the group from Nottingham.29 They reported a local recurrence rate of 6% in a group of 48 patients treated with excision only and with margins greater than 10 mm. These results were updated by Blamey at the fourth consensus conference of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer held in Heemskerk, the Netherlands, earlier this year, and they continued to support the critically important role of adequate margin width.

Outcome after recurrence

Local recurrence after treatment for ductal carcinoma in situ is demoralising and, if invasive, a threat to life. In most reported series, approximately 50% of all local recurrences are invasive.3,6,10 For this review, I have updated the Van Nuys series to June 1997 to include a total of 707 patients. There have been 74 recurrences—35 invasive and 39 non-invasive (table 2). All of the patients with non-invasive recurrences did well. None developed distant disease and there were no deaths from breast cancer.30

Table 2.

Outcome after recurrence in 707 patients with ductal carcinoma in situ analysed in relation to treatment*

| Mastectomy | Excision and radiation | Excision only | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients (n=707) | 259 | 208 | 240 |

| Total recurrences (n=74) | 2 | 36 | 36 |

| Invasive recurrences (n=35) | 2 | 18 | 15 |

| Distant metastases (n=7) | 1 | 5 | 1 |

| Breast cancer deaths (n=5) | 0 | 4 | 1 |

| Average tumour size (mm) | 40 | 18 | 14 |

| Local recurrence rate (%) | 0.5 | 16 | 21 |

| Distant recurrence rate (%) | 0.5 | 3.4 | 1 |

| Mortality from breast cancer (%) | 0 | 3 | 0.9 |

| Mortality from all causes (%) | 6 | 7 | 9 |

All values for recurrences and mortality are Kaplan-Meier estimates at eight years.

Among the 35 patients with invasive recurrences, half presented with stage 1 disease and the other half with stage 2A or more. Seven patients developed distant disease and five died of breast cancer. The median follow up for the 35 patients with invasive recurrences was 9.3 years. Breast cancer mortality at eight years, calculated by the Kaplan-Meier method, was 14%, and the rate of occurrence for distant disease was 27%. Both rates were similar to the ones reported by Solin et al.31,32 Invasive recurrence after treatment for ductal carcinoma in situ is important. It converts a patient who had stage 0 disease to one with, on average, stage 2A breast cancer (range stage 1 to stage 4).

The treatment for a patient with an invasive recurrence should be based on the stage of the recurrence. Patients treated initially by mastectomy generally require excision of the recurrence followed by radiotherapy to the chest wall and chemotherapy. Patients previously treated by excision and radiotherapy generally require mastectomy, followed by chemotherapy if the invasive recurrence is high grade or greater than 1 cm in diameter, or the markers for prognosis are poor. Patients previously treated by excision only, can undergo re-excision. If clear margins are obtained, they can be considered for breast preservation with radiotherapy. Many, however, will probably opt for mastectomy. The decision to add adjuvant chemotherapy should be based on tumour factors. We must not lose sight of the fact that, overall, patients with ductal carcinoma in situ have a good outlook. When our entire series of 707 patients is considered, the chance of an invasive recurrence at eight years is 7% and the probability of a death from breast cancer is only 1.4%. It is, however, a tragedy when ductal carcinoma in situ recurs as invasive breast cancer and the patient goes on to die of the disease. Patients treated with breast conservation surgery should be followed closely. At our centre, they are examined physically every six months ... forever. Mammography is performed every six months on the ipsilateral breast and on the contralateral breast yearly.

The future

Until recently, our approaches to ductal carcinoma in situ have been based on its morphology rather than its aetiology. The focus of investigation is now shifting to genotype rather than phenotype. Morphologically normal looking tissue surrounding areas of ductal carcinoma in situ may show losses of heterozygosity similar to the primary tumour.33–36 It is highly likely that genetic changes precede morphological evidence of malignant transformation. Medicine must learn how to recognise these genetic changes, how to exploit them, and, in the future, how to prevent them. Ductal carcinoma in situ is a lesion in which the complete malignant phenotype of unlimited growth, angiogenesis, genomic elasticity, invasion, and metastasis has not been fully expressed. With sufficient time, most non-invasive lesions will develop the ability to invade and metastasise. We must learn how to prevent this.

Footnotes

Funding: No additional funding.

Conflict of interest: None.

References

- 1.Nemoto T, Vana J, Bedwani RN, Baker HW, McGregor FH, Murphy GP. Management and survival of female breast cancer: results of a national survey by the American College of Surgeons. Cancer. 1980;45:2917–2924. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19800615)45:12<2917::aid-cncr2820451203>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Silverstein MJ, editor. Ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Landis SH, Murray T, Bolden S, Wingo PA. Cancer statistics, 1998. CA Cancer J Clin. 1998;48:6–29. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.48.1.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Silverstein MJ, Gamagami P, Colburn WJ. Coordinated biopsy team: surgical, pathologic and radiologic issues. In: Silverstein MJ, editor. Ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins; 1997. pp. 333–342. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schwartz GF, Lagios MD, Carter D, Conolly J, Ellis IO, Eusebi V, et al. for the Consensus Conference Committee. Consensus conference on the classification of ductal carcinoma in situ Cancer 1997801798–1802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Silverstein MJ, Barth A, Poller DN, Colburn WJ, Waisman JR, Gierson ED, et al. Ten-year results comparing mastectomy to excision and radiation therapy for ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. Eur J Cancer. 1995;31:1425–1427. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(95)00283-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Silverstein MJ, Poller DN, Waisman JR, Gierson ED, Colburn WJ, Waisman JR, et al. Prognostic classification of breast ductal carcinoma in situ. Lancet. 1995;345:1154–1157. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)90982-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Silverstein MJ, Lagios MD, Craig PH, Waisman JR, Lewinsky BS, Colburn WJ, et al. A prognostic index for ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. Cancer. 1996;77:2267–2274. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19960601)77:11<2267::AID-CNCR13>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lagios NM, Margolin FR, Westdahl PR, Rose NM. Mammographically detected duct carcinoma in situ. Frequency of local recurrence following tylectomy and prognostic effect of nuclear grade on local recurrence. Cancer. 1989;63:619–624. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19890215)63:4<618::aid-cncr2820630403>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Solin LJ, Yet I-T, Kurtz J, Fourquet A, Recht A, Kuske R, et al. Ductal carcinoma in situ (intraductal carcinoma) of the breast treated with breast-conserving surgery and definitive irradiation. Correlation of pathologic parameters with outcome of treatment. Cancer. 1993;71:2532–2542. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19930415)71:8<2532::aid-cncr2820710817>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bellamy COC, McDonald C, Salter DM, Chetty U, Anderson TJ. Noninvasive ductal carcinoma of the breast. The relevance of histologic categorization. Hum Pathol. 1993;24:16–23. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(93)90057-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Silverstein MJ. Predicting local recurrence in patient with ductal carcinoma in situ. In: Silverstein MJ, editor. Ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins; 1997. pp. 271–284. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fisher ER, Constantino J, Fisher B, Palekar AS, Paik SM, Suarez CM, et al. Pathologic finding from the national surgical adjuvant breast project (NSABP) protocol B-17: intraductal carcinoma (ductal carcinoma in situ) Cancer. 1995;75:1310–1319. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19950315)75:6<1310::aid-cncr2820750613>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Douglas-Jones AG, Gupta SK, Attanoos RL, Morgan JM, Mansel RE. A critical appraisal of six modern classifications of ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast (DCIS): correlation with grade of associated invasive disease. Histopathology. 1996;29:397–409. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.1996.d01-513.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fisher B, Costantino J, Redmond C, Fisher ER, Margolese R, Dimitrov N, et al. Lumpectomy compared with lumpectomy and radiation therapy for the treatment of intraductal breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1581–1586. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199306033282201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fisher B, Dignam J, Wolmark N, Mamounas E, Constantino J, Poller W, et al. Lumpectomy and radiation therapy for the treatment of intraductal breast cancer: findings from national surgical adjuvant breast and bowel project B-17. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:441–452. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.2.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lagios MD, Page DL. Radiation therapy for in situ or localized breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 1993;21:1577–1578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Page DL, Lagios MD. Pathologic analysis of the NSABP-B17 trial. Unanswered questions remaining unanswered considering current concepts of ductal carcinoma in situ. Cancer. 1995;75:1219–1222. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19950315)75:6<1219::aid-cncr2820750602>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Recht A. Side effects of radiation therapy. In: Silverstein MJ, editor. Ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins; 1997. pp. 347–350. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Page DL, Dupont WD, Rogers LW, Jensen RA, Schuyler PA. Continued local recurrence of carcinoma 15-25 years after a diagnosis of low grade ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast treated only by biopsy. Cancer. 1995;76:1197–1200. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19951001)76:7<1197::aid-cncr2820760715>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hansen N, Giuiliano A. Axillary dissection for ductal carcinoma in situ. In: Silverstein MJ, editor. Ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins; 1997. pp. 577–584. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Silverstein MJ, Rosser RJ, Gierson ED, Waisman JR, Gamagami P, Hoffman R, et al. Axillary dissection for intraductal breast carcinoma—is it indicated? Cancer. 1987;59:1819–1824. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19870515)59:10<1819::aid-cncr2820591023>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Giuliano AE, Dale PS, Turner RR, Morton DL, Evans SW, Krasne DL. Improved axillary staging of breast cancer with sentinel lymphadenectomy. Ann Surg. 1995;222:394–401. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199509000-00016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Albertini JJ, Lyman GH, Cox C, Yeatman T, Balducci L, Ku N, et al. Lymphatic mapping and sentinel node biopsy in the patient with breast cancer. JAMA. 1996;276:1818–1822. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krag DN, Weaver DL, Alex JC, Fairbank JT. Surgical resection and radiolocalization of sentinel lymph node in breast cancer using a gamma probe. Surg Oncol. 1993;2:335–340. doi: 10.1016/0960-7404(93)90064-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holland R, Faverly DRG. Whole organ studies. In: Silverstein MJ, editor. Ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins; 1997. pp. 233–240. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Silverstein MJ, Lagios MD, Lewinsky BS, Colburn WJ, Beron P, Craig PH, et al. Breast irradiation is unnecessary for widely excised ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) [abstract] Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1997;46:23. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Silverstein MJ, Lagios MD, Waisman JR, Martino S, Beron P, Lewinsky BS, et al. Margin width: a critical determinant of local control in patients with ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) of the breast [abstract] Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 1998;17:120A. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sibbering MD, Blamer RW. Nottingham experience. In: Silverstein MJ, editor. Ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins; 1997. pp. 367–372. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Silverstein MJ, Lagios MD, Martino S, Lewinsky BS, Craig PH, Beron P, et al. Outcome after invasive local recurrence in patients with ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:1367–1373. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.4.1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Solin LJ, Kurtz J, Fourquet A, Amalric R, Recht A, Bornstein BA, et al. Fifteen year results of breast conserving surgery and definitive breast irradiation for treatment of ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:754–763. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.3.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Solin LJ, Fourquet A, McCormick B, Haffty B, Recht A, Schultz DJ, et al. Salvage treatment for local recurrence following breast conserving surgery and definitive irradiation for ductal carcinoma in situ (intraductal carcinoma) of the breast. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1994;30:3–9. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(94)90512-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lakhani SR, Collins N, Stratton MR, Sloane JP. Atypical ductal hyperplasia: clonal proliferation with loss of heterozygosity on chromosomes 16q and 17p. J Clin Pathol. 1995;48:611–615. doi: 10.1136/jcp.48.7.611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stratton MR, Collins N, Lakhani SR, Sloane JP. Loss of heterozygosity in ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. J Pathol. 1995;175:195–201. doi: 10.1002/path.1711750207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Radford DM, Phillips NJ, Fair KL, Ritter JH, Holt M, Donis-Keller H. Allelic loss and the progression of breast cancer. Cancer Res. 1995;55:5180–5183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fujii H, Marsh C, Cairns P, Sidranksy D, Gabrielson E. Genetic divergence in the clonal evolution of breast cancer. Cancer Res. 1996;56:1493–1497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]