It must surely be every drug company’s dream: to have a product so sexy that the need for marketing and public relations has been obviated by a tidal wave of media hype. Since March 1998, when the little blue pills became available in the United States, we have had news stories, regular updates, features, television and radio programmes, and even serious broadsheet editorials on the myths and legends of what has been dubbed the “Pfizer riser.”

Sadly for Pfizer, however, this very hype may be their undoing. The predicted demand for Viagra (sildenafil), and the consequences this demand is expected to have for the national drug budget, has caused the British government to ban its prescription on the NHS, at least for the time being (p 765).

However, it is better to have realised that this drug has critical implications and delay it now (albeit somewhat late in the day considering how long the man in the street has known about Viagra), than blushingly use the retrospectoscope when all hope of control—legal or otherwise—has long gone.

The debate about who should eventually be able to prescribe sildenafil continues to rage. Most general practitioners I know are rather hoping it will become a drug to be prescribed by specialists only. There are two reasons for this. Firstly, it is notoriously difficult to make a diagnosis of true erectile dysfunction—despite Pfizer’s chairman and managing director protesting to the Times on 7 September that “the diagnosis is straightforward ... and best carried out by GPs”—in the knowledge that there may well be a widespread attempt to misuse the drug. Secondly, the cost of the drug may well break the bank, particularly if prescribing it becomes an indiscriminate exercise. As primary care groups become a reality, with fixed prescribing budgets being shared by large groups of general practitioners, this fear has to be taken seriously.

On the other hand, urologists have voted almost unanimously that the prescribing of sildenafil need not be confined to specialists. They argue that their outpatient clinics will become overburdened with impotent men who will now come out of the closet knowing that an acceptable oral solution to their problems now exists. And no doubt hospital drug budgets will also come under fire. The urologists have a point. But if erectile dysfunction becomes less of a taboo subject simply because there is now a more viable treatment than vacuum therapy or penile injections, and a needs assessment reveals the true prevalence of the condition, there will be plenty of pressure to review the budget set aside for it.

Touted as the latest “wonder drug,” sildenafil’s discovery and introduction follow the pattern of Prozac (fluoxetine). Sildenafil was first discovered by accident—in this case, to be a useful addition to the dispensing repertoire for men who have erectile dysfunction as a result of diabetes and some vascular disorders. Then word got around that it might also enhance sexual performance for those with no obvious impairment. Speculation became “fact,” and very quickly the drug arrived in Britain via the internet and was brought in by the caseload for anyone willing to pay for it. By 30 August, reporters from the Sunday Times were being offered it as a recreational drug on the British club scene. Coke and “poke” apparently make “a great combination.”

Arguably, this drug has been adopted by the media circus simply because sex sells newspapers. But two recent television programmes, all vying for viewers in the days just before sildenafil was awarded its European licence, opened up the debate and were (in some cases) very informative. On 9 September, Channel 4 gave its primetime slot to The Rise and Rise of Viagra. This was a long, somewhat gratuitous review of some of the people who have taken sildenafil on both sides of the Atlantic. I found this programme cliché ridden, very superficial, and, sadly, by the time I heard the comment “no one recognised it was going to be so large,” rather boring.

In contrast, Sexual Chemistry (a Horizon special) shown on BBC2 the following day was far superior. This was a much more in-depth analysis of the drug and explained how it actually works. Knowing what sildenafil does, the presenter explained, has encouraged a whole new exploration of sexuality from a scientific point of view. The action of the drug works by blocking the “off switch” which controls local soft tissue relaxation in the penis and subsequent vasodilatation. This in turn is mediated by nitric oxide. The drug alone does not cause an erection: sexual stimulation is still required to achieve the desired result.

A similar process may well be going on in women, and research is being conducted into the effects of sildenafil on postmenopausal women who seem to have lost their sexual response, particularly after pelvic surgery. The whole of female pelvic anatomy may be redefined once the female response to sildenafil is documented. The computer graphics were superb, the script was well crafted, and the programme had me hooked. I began to lose my cynicism about the drug.

The media are now entering stage two, with the broadsheets beginning to enter into serious and open discussions about rationing and budgets. No wonder Pfizer is getting worried. On 11 September both the Daily Telegraph and the Times published intelligent and accurate discussions about the difficulties this drug brings to those with responsibility for the NHS purse strings. Estimates of the annual cost waver between £1.25bn (from the BMA’s conference in July) to no more than £50m (from Pfizer itself). The true figure will probably fall somewhere between the two. And ultimately, of course, the cost will reflect the rationing of sex.

Clearly, sildenafil is perceived as reaching parts that other drugs cannot reach. Like fluoxetine, it holds a promise that our lives will be transformed by taking it. And, like fluoxetine, there will doubtless be a backlash against it. Eventually, when the honeymoon is over, I hope that sildenafil will find a sensible niche so that the “deserving impotent” will benefit from it on the NHS.

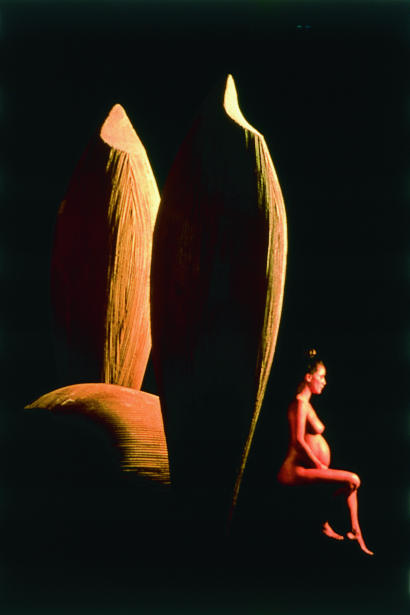

Figure.

Maria Marshall’s sculpture ‘Pod’ was created during her first pregnancy and is part of a new exhibition, Before birth. The exhibition, which aims to portray the hidden life of the unborn child, can be seen at the Wellcome Trust’s Two10 Gallery, 210 Euston Road, London NW1 2BE until 22 January.