Abstract

BACKGROUND:

In July 2023, the US Food and Drug Administration approved the first nonprescription oral contraceptive, a progestin-only pill, in the United States. Transgender, nonbinary, and gender-expansive people assigned female or intersex at birth face substantial contraceptive access barriers and may benefit from over-the-counter oral contraceptive access. However, no previous research has explored their perspectives on this topic.

OBJECTIVE:

This study aimed to measure interest in over-the-counter progestin-only pill use among transgender, nonbinary, and gender-expansive individuals assigned female or intersex at birth.

STUDY DESIGN:

We conducted an online, cross-sectional survey from May to September 2019 (before the US Food and Drug Administration approval of a progestin-only pill) among a convenience sample of transgender, nonbinary, and gender-expansive people assigned female or intersex at birth who were aged 18 to 49 years from across the United States. Using descriptive statistics and logistic regression analyses, we estimated interest in over-the-counter progestin-only pill use (our outcome) overall and by sociodemographic and reproductive health characteristics (our exposures). We evaluated separate logistic regression models for each exposure. In each model, we included the minimally sufficient adjustment set to control for confounding pathways between the exposure and outcome. For the model for age, we ran a univariable logistic regression model; for all other exposures, we ran multivariable logistic regression models.

RESULTS:

Among 1415 participants in our sample (median age, 26 years), 45.0% (636/1415; 95% confidence interval, 42.3–47.6) were interested in over-the-counter progestin-only pill use. In separate logistic regression models for each exposure, there were higher odds of interest among participants who were aged 18 to 24 years (odds ratio, 1.67; 95% confidence interval, 1.33–2.10; vs those aged 25–34 years), those who were uninsured (adjusted odds ratio, 1.91; 95% confidence interval, 1.24–2.93; vs insured), those who currently used oral contraceptives (adjusted odds ratio, 1.69; 95% confidence interval, 1.17–2.44; vs non-users), had ≤high school degree (adjusted odds ratio, 3.02; 95% confidence interval, 1.94–4.71; vs college degree), had ever used progestin-only pills (adjusted odds ratio, 2.32; 95% confidence interval, 1.70–3.17; vs never users), and who wanted to avoid estrogen generally (adjusted odds ratio, 1.32; 95% confidence interval, 1.04–1.67; vs those who did not want to avoid estrogen generally) or specifically because they viewed it as a feminizing hormone (adjusted odds ratio, 1.72; 95% confidence interval, 1.36–2.19; vs those who did not want to avoid estrogen because they viewed it as a feminizing hormone). There were lower odds of interest among participants with a graduate or professional degree (adjusted odds ratio, 0.70; 95% confidence interval, 0.51–0.96; vs college degree), those who were sterilized (adjusted odds ratio, 0.31; 95% confidence interval, 0.12–0.79; vs not sterilized), and those who had ever used testosterone for gender affirmation (adjusted odds ratio, 0.72; 95% confidence interval, 0.57–0.90; vs never users).

CONCLUSION:

Transgender, nonbinary, and gender-expansive individuals were interested in over-the-counter progestin-only pill use, and its availability has the potential to improve contraceptive access for this population.

Keywords: contraception, equity, equity, gender expression or identity, equity, sexual orientation, family planning, health disparities, health policy and health economics, LGBTQ+ health, transgender patient care

Introduction

In July 2023, the US Food and Drug Administration approved the first nonprescription oral contraceptive, a progestin-only pill, in the United States.1 For over-the-counter access to advance health equity, it is critical to center the voices of those currently facing access barriers caused by systemic forms of oppression. Although a previous nationally representative survey found that 29% of US teens and 39% of US adults at risk for unintended pregnancy and who reported their sex as female were interested in using over-the-counter progestin-only pills,2 after review of the medical literature using PubMed, we did not identify any studies that have explored the perspectives of transgender, nonbinary, and gender-expansive individuals.

In a limited number of previous studies published on the topic, 20% to 37% of self-identified transgender men reported current contraception use, and 60% to 85% reported ever contraception use.3–5 Contraception can play an important role in gender affirmation for transgender, nonbinary, and gender-expansive individuals through pregnancy prevention and by reducing or stopping menstrual bleeding, cramping, and other related symptoms.6 For individuals with tubal ligations, hormonal contraception may also be used for noncontraceptive benefits, for example to reduce menstrual bleeding.

Transgender, nonbinary, and gender-expansive people face numerous systemic barriers to accessing healthcare, including reproductive healthcare. These include provider assumptions and biases, discomfort, and lack of knowledge and experience on best practices related to treating transgender, nonbinary, and gender-expansive people.7–11 In a 2015 survey of 27,715 transgender people in the United States, one-third of participants who saw a healthcare provider in the previous year reported negative experiences related to their gender identity, and nearly one-quarter reported not seeking healthcare because of a fear of mistreatment.7 Some transgender people experience discomfort and avoid seeking reproductive healthcare because of previous negative experiences and assumptions of many healthcare settings, often labeled women’s healthcare.9,11 Over-the-counter oral contraceptives could afford greater autonomy and access to contraceptive care without discrimination, stigma, and harm that some transgender, nonbinary, and gender-expansive individuals experience in healthcare settings.

Our study objective was to measure the proportion of transgender, nonbinary, and gender-expansive people assigned female or intersex at birth in our sample who would likely use over-the-counter progestin-only pills and to measure the sociodemographic and reproductive health exposures associated with interest. We hypothesized that transgender, nonbinary, and gender-expansive people assigned female or intersex at birth would be interested in over-the-counter progestin-only pills because of easier access when compared with access only after a provider visit, the lack of estrogen, or both.

Materials and Methods

We conducted a self-administered, online, cross-sectional survey about sexual and reproductive health experiences, needs, and preferences from May to September 2019 with a convenience sample of transgender, nonbinary, and gender-expansive people assigned female or intersex at birth. Eligibility included being assigned female or intersex at birth and identifying as any gender other than exclusively as woman and/or cisgender woman; being aged 18 to 49 years; residing in the United States; and being able to complete the survey in English. We enrolled participants via (1) an anonymous, open, online survey and (2) participation in The Population Research in Identity and Disparities for Equality (PRIDE) Study,12 an online, prospective cohort study of people living in the United States who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer (LGBTQ+) or another sexual or gender minority (pridestudy.org). We used the open survey to augment The PRIDE Study sample and capture eligible people who wanted to participate in a cross-sectional survey but not in a larger, longitudinal cohort study. We recruited participants for the open survey using social media posts; community-based outreach through transgender, nonbinary, and gender-expansive-related organizations, e-mail distribution lists, and community events; and through flyers that were distributed at academic and community conferences. Recruitment efforts directed participants to a study website that included the eligibility criteria, the compensation amount, and the study objective (to learn about the sexual and reproductive health experiences of transgender, nonbinary, and gender-expansive individuals). Given that the aims of the study were primarily descriptive and our ability to recruit the population at the time was uncertain, we targeted a minimum sample size of 200 individuals.

We co-created the survey questions with a community advisory team and The PRIDE Study’s Research and Participant Advisory Committees and administered the survey using Qualtrics (Qualtrics, Provo, UT). Acknowledging that survey language has the potential to induce gender dysphoria and/or feelings of empowerment, we asked participants to provide the words they use to talk about their body parts (eg, uterus, vagina) and their experiences related to sex and fertility (eg, pregnancy, contraception). We used those responses to customize the survey text. In this manuscript, when quoting survey text, we indicate customizable words with curly brackets (ie, {}). Details on how we collected the customizable survey text are included in Appendix A. Additional survey details have been described previously.13 Participants could enter a raffle to win 1 of 100 electronic gift cards to the value of $50.

This study was approved by the institutional review boards of Stanford University and the University of California, San Francisco, and was also overseen for ongoing analysis by the WCG Institutional Review Board. In addition, The PRIDE Study Research Advisory Committee and the PRIDEnet Participant Advisory Committee (pridestudy.org/pridenet) reviewed and approved the study. All participants completed an informed consent form. We used the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology checklist to report our findings.14

The primary outcome of our analysis was interest in using over-the-counter progestin-only pills. We measured interest in over-the-counter progestin-only pills by asking the following: “Would you use a {birth control} pill that only had progestin that you could buy over the counter (without a prescription)? Progestin-only pills (also called the “mini-pill”) are a pill taken daily by the mouth that do not contain estrogen, and instead release only one type of hormone, progestin. This hormone works by stopping the {ovaries} from releasing eggs and by thickening the cervical mucus and thinning the lining of the {uterus}. Progestin is not a feminizing hormone and does not interfere with gender affirmation/HRT [gender-affirming hormone replacement therapy]/medical transition.” We coded participants as being interested in using over-the-counter progestin-only pills if they responded “Yes” (vs “No” or “Don’t know”).

Sociodemographic survey variables included age (coded into categories from a numeric response question) and categorical questions for gender identity, sexual orientation, race and ethnicity, relationship status, region, education, current employment and student status, food stamp assistance, and insurance status. To ensure adequate sample sizes for our regression analyses, we combined the following race categories into 1 category for Asian and Pacific Islander: Central Asian, East Asian, Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander, South Asian, and South East Asian. Reproductive health variables included ever having been pregnant (coded as “Yes” vs “No” from a numeric response question on number of times pregnant) and categorical questions for whether they considered themselves as being at risk for unintended pregnancy, whether they had penis-in-vagina sex with anyone who produces sperm in the previous year, ever or current contraceptive use (overall, oral contraceptives, and progestin-only pills), whether they were sterilized (described to participants as having had their tubes tied, ovaries removed, and/or uterus removed or other procedure that makes getting pregnant impossible), ever use of contraception or testosterone for gender affirmation, opinions about avoiding estrogen generally or avoiding estrogen because they viewed it as a female or feminizing hormone, and negative experiences in healthcare settings related to gender identity and/or sexual orientation. Additional details on how we collected and coded these measures are included in Appendix A.

In addition, we asked all participants if they had legally changed their gender on their health insurance. If they had, we asked if their legal gender had ever prevented them from having contraception covered by insurance. We also asked all participants if a provider had ever discussed contraception for pregnancy prevention with them (initiated by the participant or provider). If they had, we asked how comfortable they felt asking their provider questions about contraception.

We used Stata version 15.1 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX) to calculate descriptive statistics, 2-sided exact (Clopper-Pearson) 95% confidence intervals (CIs) around proportions, and univariable and multivariable logistic regression analyses to estimate interest in over-the-counter progestin-only pill use overall and by sociodemographic and reproductive health characteristics. We included missing data as a category in tables but excluded “Missing” and “Prefer not to say” responses in logistic regression analyses. In our multivariable logistic regression analyses (with a significance threshold of P<.05), exposures included sociodemographic and reproductive health variables that were significant in univariable logistic regression analyses and variables specific to transgender, nonbinary, and gender-expansive experiences that we hypothesized, a priori, might predict interest (ever use of contraception for gender affirmation; ever use of testosterone for gender affirmation; wanting to avoid estrogen generally or as a female or feminizing hormone; and negative experiences in healthcare settings related to gender identity and/or sexual orientation).

Our primary research question involved exploring the relationship between 15 different exposures and a single outcome (interest in over-the-counter progestin-only pill use). Because the specific relationships among confounders, mediators, and effect modifiers or interactions can (and do) differ for each of the 15 exposures of interest and the outcome, best practice epidemiologic methods require the construction of a separate model for each exposure-outcome association to avoid what is known as the Table 2 Fallacy.15 Thus, we constructed separate models for each exposure-outcome pair and reported the coefficient or measure of the association for the primary exposure only (because the coefficients for each confounder vary depending on the nature of each individual exposure-outcome relationship). We identified potential confounders for each exposure by constructing directed acyclic graphs using Dagitty, version 3.0 (Nijmegen, The Netherlands) (Appendix B).16 We selected sociodemographic and reproductive health variables that could be potential confounders from Tables 1 and 2 as candidates for model inclusion. Reference groups were based on largest sample size or in accordance with previous literature.2 In each model, we included the minimally sufficient adjustment set to control for confounding pathways between the exposure and outcome. For the model for age, we evaluated a univariable logistic regression model; for all other exposures, we evaluated multivariable logistic regression models. For all models, we assessed potential collinearity by calculating variance inflation factors; no collinear variables were found within the final adjustment set for each exposure. In exploring the association between education and interest in over-the-counter progestin-only pills, we evaluated an additional model with an interaction term for age and education given evidence of effect modification of the exposure-outcome relationship across ages. Because of sample size limitations, we used univariable logistic regressions for analyses of over-the-counter interest among subsamples who had legally changed their gender on their health insurance and who had ever discussed contraception with a provider.

Table 1.

Participant demographic characteristics overall and by interest in over-the-counter progestin-only pill use among an online sample of transgender, nonbinary, and gender-expansive people assigned female or intersex at birth in the United States

| Total sample |

Interested in over-the-counter progestin-only pill usea |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | n | % | n | % |

|

| ||||

| Total sample | 1415 | 100.0 | 636 | 45.0 |

|

| ||||

| Demographics | ||||

|

| ||||

| Median age (y) (IQR) | 26 (22–31) | 25 (22–30) | ||

|

| ||||

| Age (y) | ||||

|

| ||||

| 18–24 | 580 | 41.0 | 309 | 53.3 |

|

| ||||

| 25–34 | 629 | 44.5 | 255 | 40.5 |

|

| ||||

| 35–44 | 174 | 12.3 | 64 | 36.8 |

|

| ||||

| 45–49 | 32 | 2.3 | 8 | 25.0 |

|

| ||||

| Gender identitiesb | ||||

|

| ||||

| Agender | 206 | 14.6 | 88 | 42.7 |

|

| ||||

| Cisgender man | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

|

| ||||

| Cisgender womanc | 88 | 6.2 | 36 | 40.9 |

|

| ||||

| Genderqueer | 591 | 41.8 | 262 | 44.3 |

|

| ||||

| Man | 201 | 14.2 | 80 | 39.8 |

|

| ||||

| Nonbinary | 778 | 55.0 | 358 | 46.0 |

|

| ||||

| Transgender man | 502 | 35.5 | 227 | 45.2 |

|

| ||||

| Transgender woman | 2 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.0 |

|

| ||||

| Two-spirit | 17 | 1.2 | 12 | 70.6 |

|

| ||||

| Womanc | 185 | 13.1 | 76 | 41.1 |

|

| ||||

| Additional gender identity | 176 | 12.4 | 79 | 44.9 |

|

| ||||

| Multiple gender identities | 882 | 62.3 | 385 | 43.7 |

|

| ||||

| Sex assigned at birth | ||||

|

| ||||

| Female | 1412 | 99.8 | 635 | 45.0 |

|

| ||||

| Intersex | 1 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.0 |

|

| ||||

| Sex was not assigned at birth | 1 | 0.1 | 1 | 100.0 |

|

| ||||

| Prefer not to say | 1 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.0 |

|

| ||||

| Sexual orientationb | ||||

|

| ||||

| Asexual | 227 | 16.0 | 99 | 43.6 |

|

| ||||

| Bisexual | 508 | 35.9 | 209 | 41.1 |

|

| ||||

| Gay | 289 | 20.4 | 124 | 42.9 |

|

| ||||

| Lesbian | 192 | 13.6 | 83 | 43.2 |

|

| ||||

| Pansexual | 362 | 25.6 | 173 | 47.8 |

|

| ||||

| Queer | 995 | 70.3 | 434 | 43.6 |

|

| ||||

| Questioning | 60 | 4.2 | 24 | 40.0 |

|

| ||||

| Same-gender loving | 95 | 6.7 | 49 | 51.6 |

|

| ||||

| Straight or heterosexual | 41 | 2.9 | 16 | 39.0 |

|

| ||||

| Another sexual orientation | 107 | 7.6 | 46 | 43.0 |

|

| ||||

| Multiple sexual orientations | 892 | 63.0 | 394 | 44.2 |

|

| ||||

| Race and ethnicityb | ||||

|

| ||||

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 33 | 2.3 | 17 | 51.5 |

|

| ||||

| Asian, Central | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

|

| ||||

| Asian, East | 40 | 2.8 | 21 | 52.5 |

|

| ||||

| Asian, South | 17 | 1.2 | 5 | 29.4 |

|

| ||||

| Asian, Southeast | 26 | 1.8 | 11 | 42.3 |

|

| ||||

| Black or African American | 60 | 4.2 | 32 | 53.3 |

|

| ||||

| Hispanic or Latinx | 94 | 6.6 | 51 | 54.3 |

|

| ||||

| Middle Eastern or North African | 17 | 1.2 | 5 | 29.4 |

|

| ||||

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 5 | 0.4 | 2 | 40.0 |

|

| ||||

| White | 1271 | 89.8 | 562 | 44.2 |

|

| ||||

| Multiple racial and ethnic identities | 179 | 12.7 | 83 | 46.4 |

|

| ||||

| None of the above | 11 | 0.8 | 3 | 27.3 |

|

| ||||

| Missing | 20 | 1.4 | 10 | 50.0 |

|

| ||||

| Relationship status | ||||

|

| ||||

| Single, never married | 1026 | 72.5 | 481 | 46.9 |

|

| ||||

| Married, civil union, domestic partnership, engaged | 280 | 19.8 | 106 | 37.9 |

|

| ||||

| Divorced, widowed, separated | 70 | 5.0 | 29 | 41.4 |

|

| ||||

| Other | 25 | 1.8 | 11 | 44.0 |

|

| ||||

| Missing | 14 | 1.0 | 9 | 64.3 |

|

| ||||

| Region | ||||

|

| ||||

| Midwest | 277 | 19.6 | 128 | 46.2 |

|

| ||||

| Northeast | 355 | 25.1 | 148 | 41.7 |

|

| ||||

| South | 289 | 20.4 | 125 | 43.3 |

|

| ||||

| West | 388 | 27.4 | 184 | 47.4 |

|

| ||||

| Missing | 106 | 7.5 | 51 | 48.1 |

|

| ||||

| Education level | ||||

|

| ||||

| High school degree or less | 132 | 9.3 | 95 | 72.0 |

|

| ||||

| Some college, trade, or technical school | 371 | 26.2 | 174 | 46.9 |

|

| ||||

| College degree | 468 | 33.1 | 205 | 43.8 |

|

| ||||

| Some graduate or professional study | 104 | 7.4 | 47 | 45.2 |

|

| ||||

| Graduate or professional degree | 312 | 22.1 | 101 | 32.4 |

|

| ||||

| Missing | 28 | 2.0 | 14 | 50.0 |

|

| ||||

| Currently employed | ||||

|

| ||||

| Yes | 1044 | 73.8 | 450 | 43.1 |

|

| ||||

| No | 352 | 24.9 | 174 | 49.4 |

|

| ||||

| Missing | 19 | 1.3 | 12 | 63.2 |

|

| ||||

| Currently a student | ||||

|

| ||||

| Yes | 422 | 29.8 | 220 | 52.1 |

|

| ||||

| No | 974 | 68.8 | 404 | 41.5 |

|

| ||||

| Missing | 19 | 1.3 | 12 | 63.2 |

|

| ||||

| Food stamp assistance | ||||

|

| ||||

| Yes | 71 | 5.0 | 38 | 53.5 |

|

| ||||

| No | 1325 | 93.6 | 587 | 44.3 |

|

| ||||

| Missing | 19 | 1.3 | 11 | 57.9 |

|

| ||||

| Has health insurance | ||||

|

| ||||

| Yes | 1301 | 91.9 | 569 | 43.7 |

|

| ||||

| No or don’t know | 95 | 6.7 | 56 | 59.0 |

|

| ||||

| Missing | 19 | 1.3 | 11 | 57.9 |

The data for n=1415 people are presented.

Participants were considered interested in over-the-counter progestin-only pill use if they reported “yes” (vs “no” or “don’t know”) to a question asking if they would use a birth control pill that only had progestin that they could buy over the counter (without a prescription)

Respondents could select multiple responses for gender identity, sexual orientation, and race and ethnicity. Categories include anyone who selected that option and, as such, respondents can be represented in more than one category for each of these characteristics

Respondents who selected cisgender woman and/or woman also selected at least 1 other gender identity other than cisgender woman or woman and were therefore eligible for inclusion in our sample.

Grindlay. Transgender interest in over-the-counter progestin-only pills. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2024.

Table 2.

Participant reproductive health experiences and preferences overall and by interest in over-the-counter progestin-only pill use among an online sample of transgender, nonbinary, and gender-expansive people assigned female or intersex at birth in the United States

| Reproductive health experiences and preferences | Total sample |

Interested in over-the-counter progestin-only pill usea |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

|

| ||||

| Total sample | 1415 | 100.0 | 636 | 45.0 |

|

| ||||

| Reproductive health experiences and preferences | ||||

|

| ||||

| Ever pregnant | ||||

|

| ||||

| Yes | 157 | 11.1 | 68 | 43.3 |

|

| ||||

| No | 1256 | 88.8 | 568 | 45.2 |

|

| ||||

| Missing | 2 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.0 |

|

| ||||

| Considers self at risk for unintended pregnancy | ||||

|

| ||||

| Yes | 175 | 12.4 | 92 | 52.6 |

|

| ||||

| No or do not know | 1239 | 87.6 | 544 | 43.9 |

|

| ||||

| Missing | 1 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.0 |

|

| ||||

| Has had penis-in-vagina sex with anyone who produces sperm in the previous year | ||||

|

| ||||

| Yes | 477 | 33.7 | 213 | 44.7 |

|

| ||||

| No or do not know | 936 | 66.2 | 422 | 45.1 |

|

| ||||

| Missing | 2 | 0.1 | 1 | 50.0 |

|

| ||||

| Ever contraception use | ||||

|

| ||||

| Yes | 1031 | 72.9 | 461 | 44.7 |

|

| ||||

| No or do not know | 383 | 27.1 | 175 | 45.7 |

|

| ||||

| Missing | 1 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.0 |

|

| ||||

| Current contraception use | ||||

|

| ||||

| Yes | 709 | 50.1 | 323 | 45.6 |

|

| ||||

| No or do not know | 698 | 49.3 | 310 | 44.4 |

|

| ||||

| Missing | 8 | 0.6 | 3 | 37.5 |

|

| ||||

| Ever oral contraception use | ||||

|

| ||||

| Yes | 731 | 51.7 | 331 | 45.3 |

|

| ||||

| No or do not know | 684 | 48.3 | 305 | 44.6 |

|

| ||||

| Current oral contraception use | ||||

|

| ||||

| Yes | 132 | 9.3 | 75 | 56.8 |

|

| ||||

| No or do not know | 1282 | 90.6 | 561 | 43.8 |

|

| ||||

| Missing | 1 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.0 |

|

| ||||

| Ever progestin-only pill use | ||||

|

| ||||

| Yes | 206 | 14.6 | 128 | 62.1 |

|

| ||||

| No or do not know | 1209 | 85.4 | 508 | 42.0 |

|

| ||||

| Current progestin-only pill use | ||||

|

| ||||

| Yes | 32 | 2.3 | 32 | 100.0 |

|

| ||||

| No or do not know | 1382 | 97.7 | 604 | 43.7 |

|

| ||||

| Missing | 1 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.0 |

|

| ||||

| Is sterilized or has had tubes tied, ovaries removed, and/or uterus removed or other procedure that makes getting pregnant impossible | ||||

|

| ||||

| Yes | 31 | 2.2 | 6 | 19.4 |

|

| ||||

| No | 1384 | 97.8 | 630 | 45.5 |

|

| ||||

| Ever used contraception for gender affirmation | ||||

|

| ||||

| Yes | 146 | 10.3 | 77 | 52.7 |

|

| ||||

| No or do not know | 1267 | 89.5 | 559 | 44.1 |

|

| ||||

| Missing | 2 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.0 |

|

| ||||

| Ever used testosterone for gender affirmation | ||||

|

| ||||

| Yes | 601 | 42.5 | 249 | 41.4 |

|

| ||||

| No | 814 | 57.5 | 387 | 47.5 |

|

| ||||

| Current use of testosterone for gender affirmation | ||||

|

| ||||

| Yes | 523 | 37.0 | 215 | 41.1 |

|

| ||||

| No | 892 | 63.0 | 421 | 47.2 |

|

| ||||

| Wants to avoid estrogen generally | ||||

|

| ||||

| Yes | 917 | 64.8 | 429 | 46.8 |

|

| ||||

| No or do not know | 498 | 35.2 | 207 | 41.6 |

|

| ||||

| Wants to avoid estrogen because they view it as a female or feminizing hormone | ||||

|

| ||||

| Yes | 701 | 49.5 | 351 | 50.1 |

|

| ||||

| No or do not know | 712 | 50.3 | 284 | 39.9 |

|

| ||||

| Missing | 2 | 0.1 | 1 | 50.0 |

|

| ||||

| Ever felt that opinions about their gender identity and/or sexual orientation from healthcare staff have negatively impacted them in a healthcare setting | ||||

|

| ||||

| Yes | 791 | 55.9 | 355 | 44.9 |

|

| ||||

| No or do not know | 615 | 43.5 | 277 | 45.0 |

|

| ||||

| Missing | 9 | 0.6 | 4 | 44.4 |

|

| ||||

| Legal gender on their health insurance has ever prevented them from having contraception covered by their insurance (if their gender was legally changed on health insurance, n=253) | ||||

|

| ||||

| Yes | 17 | 6.7 | 11 | 64.7 |

|

| ||||

| No or do not know | 235 | 92.9 | 87 | 37.0 |

|

| ||||

| Missing | 1 | 0.4 | 1 | 100.0 |

|

| ||||

| How comfortable did you feel asking your provider all of the questions you had about birth control? (if provider has ever discussed birth control for pregnancy prevention, n=849) | ||||

|

| ||||

| Somewhat or very comfortable | 532 | 62.7 | 243 | 45.7 |

|

| ||||

| A little comfortable | 115 | 13.6 | 64 | 55.7 |

|

| ||||

| Not at all comfortable | 86 | 10.1 | 35 | 40.7 |

|

| ||||

| I did not have questions about birth control | 110 | 13.0 | 34 | 30.9 |

|

| ||||

| Missing | 6 | 0.7 | 1 | 16.7 |

The data for n=1415 people are presented.

Participants were considered interested in over-the-counter progestin-only pill use if they reported “yes” (vs “no” or “don’t know”) to a question asking if they would use a birth control pill that only had progestin that they could buy over the counter (without a prescription).

Grindlay. Transgender interest in over-the-counter progestin-only pills. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2024.

Results

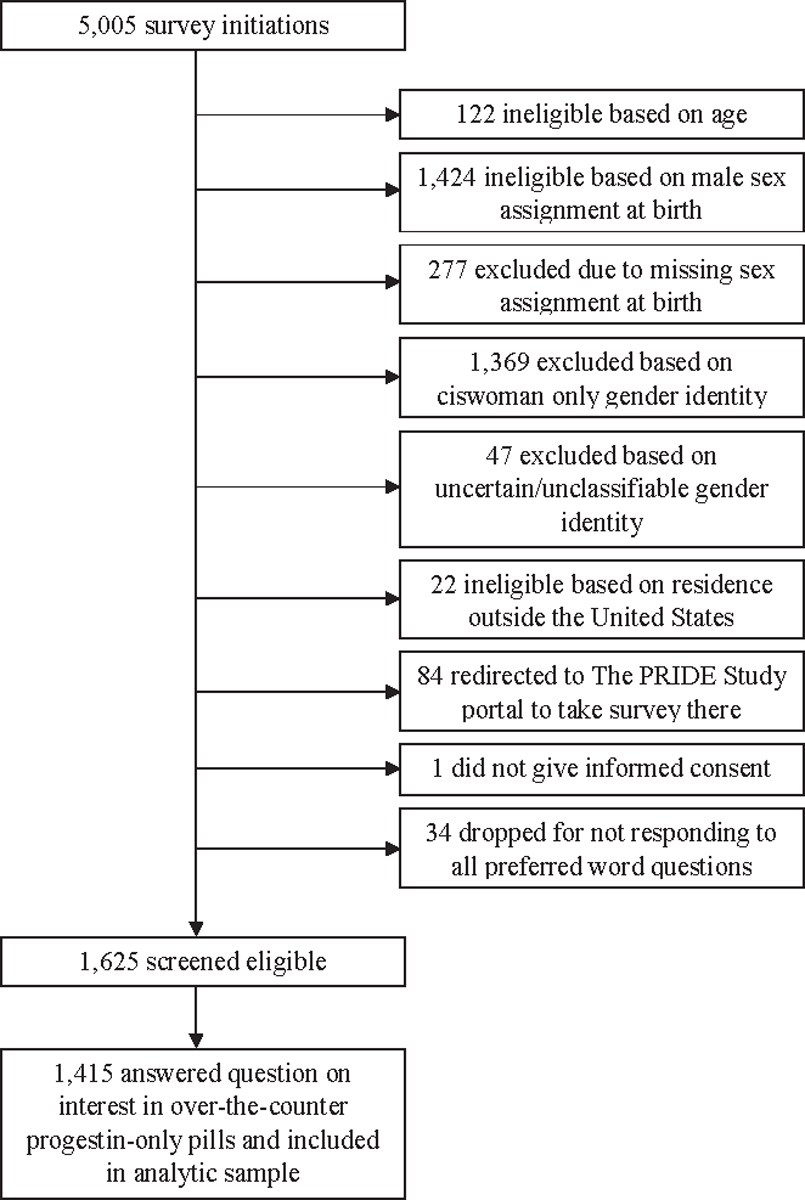

Overall, 5005 people initiated the survey (798 from the open survey and 4207 from The PRIDE Study); 1625 respondents were eligible. Of these participants, 1415 responded to the question on over-the-counter progestin-only pill interest (87.1% completion rate) and were included in our analytical sample (Figure). The median age was 26 years (interquartile range [IQR], 22–31 years), and participants most commonly identified as nonbinary (n=778; 55.0%), genderqueer (n=591; 41.8%), and transgender man (n=502; 35.5%); 282 (19.9%) identified with a race or ethnic identity other than exclusively White; and 1301 (91.9%) had health insurance (Table 1). Overall, 175 (12.4%) participants considered themselves as being at risk for unintended pregnancy; 477 (33.7%) had penis-in-vagina sex with someone who produced sperm in the previous year; 1031 (72.9%) had ever used contraception; and 709 (50.1%) were currently using it. More specifically, 731 (51.7%) participants had ever used oral contraceptives (of any type), and 132 (9.3%) were currently using them; 206 (14.6%) had ever used progestin-only pills. In our study sample, 2% (n=31) was sterilized. Among participants who had legally changed their gender on their health insurance (n=253), 6.7% (n=17) reported that it prevented them from having contraception covered by insurance. Among those who ever discussed contraception for pregnancy prevention with a provider (n=849), 62.7% (n=532) felt “somewhat comfortable” or “very comfortable” asking questions about contraception; 13.6% (n=115) felt “a little comfortable”; 10.1% (n=86) were “not at all comfortable”; and 13.0% (n 110) “did not have any questions” (Table 2).

FIGURE. Survey initiation, eligibility screening, and completion for study sample.

The PRIDE Study, The Population Research in Identity and Disparities for Equality Study.

Overall, 636 participants (45.0%; 95% CI, 42.3%–47.6%) were interested in over-the-counter progestin-only pill use (Table 1). When excluding individuals who were sterilized, a similar proportion (45.5%; 95% CI, 42.9%–48.2%) were interested in over-the-counter progestin-only pill use. In separate logistic regression models for each exposure, there were higher odds of interest among participants aged 18 to 24 years (odds ratio [OR], 1.67; 95% CI, 1.33–2.10; vs those aged 25–34 years), those with a high school degree or less (adjusted OR [aOR], 3.02; 95% CI, 1.94–4.71; vs those with a college degree), uninsured participants (aOR, 1.91; 95% CI, 1.24–2.93; vs insured participants), those who were currently using oral contraceptives (aOR, 1.69; 95% CI, 1.17–2.44; vs non-users), and those who had ever used progestin-only pills (aOR, 2.32; 95% CI, 1.70–3.17; vs never users). There were also higher odds of interest among participants who wanted to avoid estrogen generally (aOR, 1.32; 95% CI, 1.04–1.67; vs those who did not want to avoid estrogen generally) or specifically because they viewed it is a female or feminizing hormone (aOR, 1.72; 95% CI, 1.36–2.19; vs those who did not want to avoid estrogen because they viewed it as a feminizing hormone). There were lower odds of interest among those with a graduate or professional degree (aOR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.51–0.96; vs college degree), those who were sterilized (aOR, 0.31; 95% CI, 0.12–0.79; vs not sterilized), and those who had ever used testosterone for gender affirmation (aOR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.57–0.90; vs never users) (Table 3). When examining the association between education and over-the-counter progestin-only pill interest by age group, we found that those with a high school degree or less continued to have the highest interest by far. Except for those aged 35 to 44 years, individuals with a graduate or professional degree expressed interest in over-the-counter progestin-only pills less commonly than those with less education.

TABLE 3.

Logistic regression models of interest in over-the-counter progestin-only pill use among an online sample of transgender, nonbinary, and gender-expansive people assigned female or intersex at birth in the United States

| Independent variable and adjustment set to control for confounding | Interested in over-the-counter progestin-only pill usea |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio | 95% confidence interval | P value | |

|

| |||

| Model 1: age (y) (n=1415), no adjustment was necessary to estimate the total effect of this variable on interest in over-the-counter progestin-only pill use | |||

|

| |||

| 18–24 | 1.67 | 1.33–2.10 | <.001b |

|

| |||

| 25–34 (ref) | |||

|

| |||

| 35–44 | 0.85 | 0.60–1.21 | .37 |

|

| |||

| 45–49 | 0.49 | 0.22–1.11 | .09 |

|

| |||

| Model 2: education level (n=1381), adjusted for age and race and ethnicity | |||

|

| |||

| High school degree or less | 3.02 | 1.94–4.71 | <.001b |

|

| |||

| Some college, trade, or technical school | 1.04 | 0.78–1.39 | .77 |

|

| |||

| College degree (ref) | |||

|

| |||

| Some graduate or professional study | 1.12 | 0.73–1.73 | .60 |

|

| |||

| Graduate or professional degree | 0.70 | 0.51–0.96 | .03b |

|

| |||

| Model 3: currently employed (n=1383), adjusted for education | |||

|

| |||

| Yes | 0.97 | 0.75–1.26 | .84 |

|

| |||

| No (ref) | |||

|

| |||

| Model 4: currently a student (n=1396), adjusted for age | |||

|

| |||

| Yes | 1.26 | 0.98–1.61 | .07 |

|

| |||

| No (ref) | |||

|

| |||

| Model 5: marital status (n=1387), adjusted for age and education | |||

|

| |||

| Single, never married | 1.02 | 0.75–1.39 | .88 |

|

| |||

| Married, civil union, registered domestic partnership, or engaged (ref) | |||

|

| |||

| Divorced, widowed, separated | 1.23 | 0.71–2.13 | .46 |

|

| |||

| Other | 0.58 | 0.24–1.45 | .25 |

|

| |||

| Model 6: has health insurance (n=1,392), adjusted for employment, student status, and marital status | |||

|

| |||

| Yes (ref) | |||

|

| |||

| No or donť know | 1.91 | 1.24–2.93 | .003b |

|

| |||

| Model 7: considers self at risk for unintended pregnancy (n=1400), adjusted for age, marital status, and participant sterilization | |||

|

| |||

| Yes | 1.33 | 0.96–1.85 | .08 |

|

| |||

| No or do not know (ref) | |||

|

| |||

| Model 8: current oral contraceptive use (n=1394), adjusted for marital status, participant sterilization, insurance status, and considering self at risk for future unplanned pregnancy | |||

|

| |||

| Yes | 1.69 | 1.17–2.44 | .005b |

|

| |||

| No or do not know (ref) | |||

|

| |||

| Model 9: ever progestin-only pill use (n=1413), adjusted for ever having been pregnant and wanting to avoid estrogen generally | |||

|

| |||

| Yes | 2.32 | 1.70–3.17 | <.001b |

|

| |||

| No or do not know (ref) | |||

|

| |||

| Model 10: is sterilized or has had tubes tied, ovaries removed, and/or uterus removed or other procedure that makes getting pregnant impossible (n=1385), adjusted for age, education, marital status, and ever having been pregnant | |||

|

| |||

| Yes | 0.31 | 0.12–0.79 | .01b |

|

| |||

| No (ref) | |||

|

| |||

| Model 11: ever use of testosterone for gender affirmation (n=1415), adjusted for age and wanting to avoid estrogen generally | |||

|

| |||

| Yes | 0.72 | 0.57–0.90 | .004b |

|

| |||

| No (ref) | |||

|

| |||

| Model 12: has ever used contraception for gender affirmation (n=1413), adjusted for age | |||

|

| |||

| Yes | 1.31 | 0.93–1.86 | .13 |

|

| |||

| No or do not know (ref) | |||

|

| |||

| Model 13: Wants to avoid estrogen generally (n=1,415), adjusted for age and ever having used testosterone | |||

|

| |||

| Yes | 1.32 | 1.04–1.67 | .02b |

|

| |||

| No or do not know (ref) | |||

|

| |||

| Model 14: wants to avoid estrogen because they view it as a female or feminizing hormone (n=1413), adjusted for age and ever having used testosterone | |||

|

| |||

| Yes | 1.72 | 1.36–2.19 | <.001b |

|

| |||

| No or do not know (ref) | |||

|

| |||

| Model 15: ever felt that opinions about their gender identity and/or sexual orientation from healthcare staff have negatively impacted them in a healthcare setting (n=1305), adjusted for age, education, and region | |||

|

| |||

| Yes | 1.08 | 0.86–1.36 | .50 |

|

| |||

| No or do not know (ref) | |||

We used the directed acyclic graph approach16 to select covariates for each model. Supplemental Appendix B contains the directed acyclic graphs.

Participants were considered interested in over-the-counter progestin-only pill use if they reported “yes” (vs “no” or “don’t know”) to a question asking if they would use a birth control pill that only had progestin that they could buy over the counter (without a prescription)

Indicates P<.05 in logistic regression.

Grindlay. Transgender interest in over-the-counter progestin-only pills. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2024.

In univariable analyses, those who had faced challenges with contraceptive coverage because of their legal gender on their health insurance (vs never faced challenges) were more likely to report interest (64.7% vs 37.0%; P=.03). Individuals who did not have any questions about contraception were less likely to report interest than those who were somewhat or very comfortable asking their provider questions (30.9% vs 45.7%; P=.005) (Table 2).

Comment

Principal findings

Nearly half of transgender, nonbinary, and gender-expansive individuals in our sample were interested in using over-the-counter progestin-only pills. Our findings suggest that this population may be interested in over-the-counter progestin-only pills because of improved access owing to the ability to obtain it without a prescription or medical visit and the lack of estrogen in progestin-only pills.

Results in the context of what is known

Interest was relatively similar to that in a previous nationally representative survey of individuals who identified as female.2 Higher interest among uninsured individuals also mirrors previous research2,17 and emphasizes the appeal of greater access among those who lack prescription coverage and who face high appointment costs. Higher interest among those who had faced challenges with contraceptive coverage owing to their legal gender on their health insurance similarly indicates access barriers related to insurance coverage that an over-the-counter pill could help to address. However, affordable pricing is critical to realizing those benefits for transgender, nonbinary, and gender-expansive individuals, particularly given their lower socioeconomic status when compared with the general United States population.7,18,19

Negative experiences and mistrust in healthcare settings may also motivate interest in over-the-counter access. Although our survey methodology prevents direct causal conclusions, previous research has found that young people generally are more likely to experience discrimination by healthcare providers,20,21 which may play a role in the higher interest among younger participants in our sample. Furthermore, pelvic examinations can induce gender dysphoria for transgender, nonbinary, and gender-expansive individuals6 and are not medically necessary before taking oral contraception, yet many providers require them when prescribing oral contraception.22 Removing the clinical requirement may also be appealing for this reason.

Interest among those who wanted to avoid estrogen (both generally and as a feminizing hormone) indicates that the hormone makeup of progestin-only pills is an appealing feature for some. However, progestin-only pills can have gender dysphoric effects, such as chest or breast tenderness or changes to menses.6,23 Informing people about these potential effects is important so that transgender, nonbinary, and gender-expansive people can make educated choices. Ideally, multiple over-the-counter progestin-only pill formulations would be available for people to find one that works best for them.

Progestin-only pills may be of particular interest for several reasons. The small amount of estrogen in combined hormonal contraceptives has not been shown to undermine the masculinizing effects of testosterone taken for gender-affirming hormone therapy, and testosterone is not a contraindication to any contraceptive method.6,8 However, some transgender, nonbinary, and gender-expansive individuals want to avoid estrogen-containing methods because of possible side effects, such as chest or breast growth, bloating, and changes in menses.6,8,11 Progestin-only pills can also support gender affirmation by reducing or stopping menstrual bleeding without a procedure like inserting an intrauterine device, which can be both physically and psychologically invasive and stimulate gender dysphoria for some.6 Potential drawbacks of progestin-only pills include daily administration, lower contraceptive efficacy (when compared with long-acting methods), and possible gender dysphoric effects including chest or breast tenderness and breakthrough bleeding.6

Lower interest among those who use testosterone for gender affirmation may be related to assessments of unintended pregnancy risk and/or may be influenced by the duration of testosterone use. Those who have been on testosterone longer may experience reduced or no menstrual bleeding and have a lower perceived need for contraception.6,10 The lack of association between interest in over-the-counter progestin-only pills and self-assessed risk of unintended pregnancy or having had penis-in-vagina sex in the previous year suggests that nonpregnancy-related contraceptive benefits, such as menstrual suppression, are of greater importance.

Clinical implications

These findings highlight transgender, nonbinary, and gender-expansive individuals as a population interested in and who may benefit from over-the-counter oral contraceptive availability. This study adds to our understanding of the potential impacts of newly enhanced, over-the-counter progestin-only pill access. Its availability may appeal to those who face reproductive health and prescription access barriers and those who want a contraceptive method that does not contain estrogen and it may improve contraceptive access for this population. These findings highlight the importance of transgender and gender-expansive representation in the marketing of over-the-counter progestin-only pills and because real-world use may be driven by how much they feel the product is applicable to them.

Research implications

With an over-the-counter progestin-only pill now approved in the United States, future research should explore real-world uptake and experiences among transgender, nonbinary, and gender-expansive individuals.

Strengths and limitations

Our study has several limitations. First, we used convenience sampling, because there were no population-based sampling frames for transgender, nonbinary, and gender-expansive people assigned female or intersex at birth in the United States. Our results, therefore, may not be generalizable to all transgender, nonbinary, and gender-expansive individuals. In addition, passive recruiting can lead to participation bias in that those who elected to participate are more open to medical interventions (or hold other opinions) than nonparticipants. The high proportion of survey participants with health insurance (91.9%) indicates that our sample is less marginalized than the general population of transgender, nonbinary, and gender-expansive individuals. Therefore, our ability to assess the effect of insurance status on interest in over-the-counter progestin-only pills may be less robust and our findings may underestimate interest in over-the-counter progestin-only pills. Another limitation is that the vast majority of the sample was White because of the convenience sampling method. Further, some race and ethnicity categories had small sample sizes due to the numerous categories we included in the survey, which may have limited our ability to detect differences in interest by race and ethnicity. For our measure of sterilization, we were unable to distinguish between someone who had a procedure that would lead to both no possibility of pregnancy and no menstruation versus those who only had no possibility of pregnancy. The reasons that either of these 2 groups might be interested in an over-the-counter progestin-only pill or perceive its usefulness for their situation might vary considerably. A strength of our study includes the disaggregated data on race and ethnicity, which contributes to more accurate representation. Furthermore, our large sample size and analysis of transgender, nonbinary, and gender-expansive perspectives on over-the-counter progestin-only pill access provide important new information on the attitudes of this population.

Our survey was conducted before the US Food and Drug Administration approval of an over-the-counter progestin-only pill. Real-world interest and use may be higher or lower with approval now in place and will likely also be impacted by price and insurance coverage. Furthermore, this study was conducted before the COVID-19 pandemic, which changed the way many people interact with the healthcare system and led to higher rates of telemedicine24 and self-medication and care.25 These changing attitudes and practices related to self-care may lead to higher levels of interest in and comfort with over-the-counter access today. This study was also conducted before the Dobbs vs Jackson Women’s Health Organization Supreme Court decision in which the federal constitutional right to abortion was overturned, which may make people think differently about their need or desire to access contraception. Obstetrician-gynecologists reported increases in the number of people who sought contraception since the Dobbs ruling,26 and this too may lead to even greater interest in over-the-counter progestin-only pill access than we found at the time our survey was conducted. Finally, increasing restrictions on transgender care27 may also drive more interest in over-the-counter care and self-managed care.

Conclusion

Transgender, nonbinary, and gender-expansive individuals are interested in over-the-counter progestin-only pill use, and its availability has the potential to improve contraceptive access for this population.

Supplementary Material

AJOG at a Glance.

Why was this study conducted?

In July 2023, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the first nonprescription oral contraceptive, a progestin-only pill, in the United States. Transgender and gender-expansive people assigned female or intersex at birth face substantial contraceptive access barriers and may benefit from over-the-counter oral contraceptive access. However, no previous research has explored their perspectives on this topic.

Key findings

In this online, cross-sectional survey, conducted in May to September 2019 (before the FDA approval of a progestin-only pill) with a convenience sample of 1415 transgender and gender-expansive adults assigned female or intersex at birth, 45.0% were interested in over-the-counter progestin-only pill use.

What does this add to what is known?

Interest in an over-the-counter progestin-only pill is high among transgender and gender-expansive individuals assigned female or intersex at birth, and its availability has the potential to improve contraceptive access for this population.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Lyndon Cudlitz, BA, Mary Durden, MA, Laura Fix, MSW, Eli Goldberg, MD, Anna Katz, JD, Avery Lesser-Lee, BA, Laz Letcher, PhD, Anei Reyes, MSW, and Arami Stoeffler, BAx, for their support in developing the survey. We acknowledge the courage and dedication of all participants, including The PRIDE Study participants, for sharing their stories; the careful attention of PRIDEnet Participant Advisory Committee members for reviewing and improving every study application; and the enthusiastic engagement of PRIDEnet Ambassadors and Community Partners for bringing thoughtful perspectives and promoting enrollment and disseminating findings. For more information, please visit https://pridestudy.org/pridenet.

K.G., H.M., and S.R. are affiliated with Ibis Reproductive Health, which had a partnership with HRA Pharma in which Ibis provided financial support for some of the research that was part of an over-the-counter switch application to the United States Food and Drug Administration for a progestin-only pill. Ibis received no monetary compensation nor ownership of any rights to the product. Ibis raised the funding for this partnership from a private foundation and selected HRA Pharma as its partner through an open process overseen by the Oral Contraceptives Over-the-Counter Working Group steering committee in an effort to incentivize a pharmaceutical company to complete the work to make a birth control pill available over the counter. M.R.L. reports serving as a consultant for Hims, Inc (2019 to present) and Folx, Inc (2020–2021). J.O.-M. reports serving as a consultant for Sage Therapeutics (May 2017) in a 1-day advisory board, Ibis Reproductive Health (a not-for-profit research group, 2017e present), Hims, Inc (2019–present), and Folx, Inc (2020–present). J.H. reports serving as a consultant advisor for Plume, Inc (2020–present). M.R.C. reports serving on the Clinical Advisory Board of Appa Health. None of these roles present a conflict of interest related to the work described in the manuscript.

K.G. was supported by the Collaborative for Gender + Reproductive Equity. H.M., J.H., J.O.M., and S.R. were partially supported by the Society of Family Planning Research Fund. A.F. was partially supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse under grant number K23DA039800. J.O.M. was partially supported by the National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive, and Kidney Disorders under grant number K12DK111028. M.R.C. was partially supported by a Clinical Research Training Fellowship from the American Academy of Neurology and the Tourette Association of America. Research reported in this article was partially funded through a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Award under award number PPRN-1501–26848 to M.R.L. The statements in this article are solely that of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of PCORI, its Board of Governors or Methodology Committee, nor of the National Institutes of Health or the Society of Family Planning Research Fund. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Kate Grindlay, Ibis Reproductive Health, Cambridge, MA.

Juno Obedin-Maliver, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA; Department of Epidemiology and Population Health, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA; The PRIDE Study/PRIDEnet, Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA.

Sachiko Ragosta, Ibis Reproductive Health, Oakland, CA.

Jen Hastings, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, CA.

Mitchell R. Lunn, Department of Epidemiology and Population Health, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA; The PRIDE Study/PRIDEnet, Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA; Division of Nephrology, Department of Medicine, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA.

Annesa Flentje, The PRIDE Study/PRIDEnet, Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA; Department of Community Health Systems, University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, CA; Alliance Health Project, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, CA.

Matthew R. Capriotti, The PRIDE Study/PRIDEnet, Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA; Department of Psychology, San José State University, San Jose, CA.

Zubin Dastur, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA; The PRIDE Study/PRIDEnet, Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA.

Micah E. Lubensky, The PRIDE Study/PRIDEnet, Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA; Department of Community Health Systems, University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, CA.

Heidi Moseson, Ibis Reproductive Health, Oakland, CA.

References

- 1.Belluck PFDA approves first U.S. over-the-counter birth control pill. The New York Times. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2023/07/13/health/otc-birth-control-pill.html. Accessed January 31, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grindlay K, Grossman D. Interest in over-the-counter access to a progestin-only pill among women in the United States. Womens Health Issues 2018;28:144–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abern L, Maguire K. Contraception knowledge in transgender individuals: are we doing enough? [9F]. Obstet Gynecol 2018;131:65S. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Light A, Wang LF, Zeymo A, Gomez-Lobo V. Family planning and contraception use in transgender men. Contraception 2018;98:266–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stark B, Hughto JMW, Charlton BM, Deutsch MB, Potter J, Reisner SL. The contraceptive and reproductive history and planning goals of trans-masculine adults: a mixed-methods study. Contraception 2019;100:468–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krempasky C, Harris M, Abern L, Grimstad F. Contraception across the transmasculine spectrum. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2020;222:134–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.James SE, Herman JL, Rankin S, Keisling M, Mottet L, Anafi M. The report of the 2015 U.S. transgender survey. Washington, DC: National Center for Transgender Equality; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Health care for transgender and gender diverse individuals: ACOG committee opinion, number 823. Obstet Gynecol 2021;137(3):e75–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wingo E, Ingraham N, Roberts SCM. Reproductive health care priorities and barriers to effective care for LGBTQ people assigned female at birth: a qualitative study. Womens Health Issues 2018;28:350–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boudreau D, Mukerjee R. Contraception care for transmasculine individuals on testosterone therapy. J Midwifery Womens Health 2019;64:395–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gomez AM, Ðỗ L, Ratliff GA, Crego PI, Hastings J. Contraceptive beliefs, needs, and care experiences among transgender and nonbinary young adults. J Adolesc Health 2020;67:597–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lunn MR, Lubensky M, Hunt C, et al. A digital health research platform for community engagement, recruitment, and retention of sexual and gender minority adults in a national longitudinal cohort study—The PRIDE Study. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2019;26:737–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moseson H, Lunn MR, Katz A, et al. Development of an affirming and customizable electronic survey of sexual and reproductive health experiences for transgender and gender nonbinary people. PLoS One 2020;15:e0232154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. BMJ 2007;335:806–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Westreich D, Greenland S. The table 2 fallacy: presenting and interpreting confounder and modifier coefficients. Am J Epidemiol 2013;177:292–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shrier I, Platt RW. Reducing bias through directed acyclic graphs. BMC Med Res Methodol 2008;8:70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grossman D, Grindlay K, Li R, Potter JE, Trussell J, Blanchard K. Interest in over-the-counter access to oral contraceptives among women in the United States. Contraception 2013;88:544–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carpenter CS, Eppink ST, Gonzales G. Transgender status, gender identity, and socioeconomic outcomes in the United States. ILR Rev 2020;73:573–99. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crissman HP, Berger MB, Graham LF, Dalton VK. Transgender demographics: a household probability sample of US adults, 2014. Am J Public Health 2017;107:213–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nong P, Raj M, Creary M, Kardia SLR, Platt JE. Patient-reported experiences of discrimination in the US health care system. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3:e2029650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kraetschmer N, Sharpe N, Urowitz S, Deber RB. How does trust affect patient preferences for participation in decision-making? Health Expect 2004;7:317–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Henderson JT, Sawaya GF, Blum M, Stratton L, Harper CC. Pelvic examinations and access to oral hormonal contraception. Obstet Gynecol 2010;116:1257–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Raymond EG, Grossman D. Progestin-only pills. In: Hatcher RA, Nelson AL, Trussell J, et al. , eds. Contraceptive technology, 21st ed. New York, NY: Ayer Company Publishers, Inc; 2018. p. 317–26. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shaver J The state of telehealth before and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Prim Care 2022;49:517–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zheng Y, Liu J, Tang PK, Hu H, Ung COL. A systematic review of self-medication practice during the COVID-19 pandemic: implications for pharmacy practice in supporting public health measures. Front Public Health 2023;11:1184882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Frederiksen B, Ranji U, Gomez I, Salganicoff A. A national survey of OBGYNs’ experiences after Dobbs. Kaiser Family Foundation. 2023. Available at: https://files.kff.org/attachment/Report-A-National-Survey-of-OBGYNs-Experiences-After-Dobbs.pdf. Accessed January 31, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tanne JH. Transgender care: 19 US states ban or restrict access with penalties for doctors who break the law. BMJ 2023;381:1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.