Abstract

Purpose

Competency-based medical education relies on feedback from workplace-based assessment (WBA) to direct learning. Unfortunately, WBAs often lack rich narrative feedback and show bias towards Medical Expert aspects of care. Building on research examining interactive assessment approaches, the Queen’s University Internal Medicine residency program introduced a facilitated, team-based assessment initiative (“Feedback Fridays”) in July 2017, aimed at improving holistic assessment of resident performance on the inpatient medicine teaching units. In this study, we aim to explore how Feedback Fridays contributed to formative assessment of Internal Medicine residents within our current model of competency-based training.

Method

A total of 53 residents participated in facilitated, biweekly group assessment sessions during the 2017 and 2018 academic year. Each session was a 30-minute facilitated assessment discussion done with one inpatient team, which included medical students, residents, and their supervising attending. Feedback from the discussion was collected, summarized, and documented in narrative form in electronic WBA forms by the program’s assessment officer for the residents. For research purposes, verbatim transcripts of feedback sessions were analyzed thematically.

Results

The researchers identified four major themes for feedback: communication, intra- and inter-personal awareness, leadership and teamwork, and learning opportunities. Although feedback related to a broad range of activities, it showed strong emphasis on competencies within the intrinsic CanMEDS roles. Additionally, a clear formative focus in the feedback was another important finding.

Conclusions

The introduction of facilitated team-based assessment in the Queen’s Internal Medicine program filled an important gap in WBA by providing learners with detailed feedback across all CanMEDS roles and by providing constructive recommendations for identified areas for improvement.

Abstract

Objectif

La formation médicale fondée sur les compétences s'appuie sur la rétroaction faite lors de l'évaluation des apprentissages par observation directe dans le milieu de travail. Malheureusement, les évaluations dans le milieu de travail omettent souvent de fournir une rétroaction narrative exhaustive et privilégient les aspects des soins relevant de l'expertise médicale. En se basant sur la recherche ayant étudié les approches d'évaluation interactive, le programme de résidence en médecine interne de l'Université Queen's a introduit en juillet 2017 une initiative d'évaluation facilitée et en équipe (« Les vendredis rétroaction »), visant à améliorer l'évaluation holistique du rendement des résidents dans les unités d'enseignement clinique en médecine interne. Dans cette étude, nous visons à explorer comment ces « vendredis rétroaction » ont contribué à l'évaluation formative des résidents en médecine interne dans le cadre de notre modèle actuel de formation axée sur les compétences.

Méthode

Au total, 53 résidents ont participé à des séances d'évaluation de groupe facilitées et bi-hebdomadaires au cours de l'année universitaire 2017-2018. Chaque séance consistait en une discussion d'évaluation facilitée de 30 minutes menée avec une équipe de l’unité de soins, qui comprenait des étudiants en médecine, des résidents et le médecin superviseur. Les commentaires issus de la discussion ont été recueillis, résumés et documentés sous forme narrative dans des formulaires électroniques d’observation directe dans le milieu de travail par le responsable de l'évaluation du programme de résidence. À des fins de recherche, les transcriptions verbatim des séances de rétroaction ont été analysées de façon thématique.

Résultats

Les chercheurs ont identifié quatre thèmes principaux pour les commentaires : la communication, la conscience intra- et interpersonnelle, le leadership et le travail d'équipe, et les occasions d'apprentissage. Bien que la rétroaction concerne un large éventail d'activités, elle met fortement l'accent sur les compétences liées aux rôles intrinsèques de CanMEDS. De plus, le fait que la rétroaction avait un rôle clairement formatif est une autre constatation importante.

Conclusions

L'introduction de l'évaluation en équipe facilitée dans le programme de médecine interne à Queen's a comblé une lacune importante dans l'apprentissage par observation directe dans le milieu de travail en fournissant aux apprenants une rétroaction détaillée sur tous les rôles CanMEDS et en formulant des recommandations constructives sur les domaines à améliorer.

Introduction

Similar to approaches used for competency-based medical education (CBME) adopted in other countries, Canadian postgraduate medical education (PGME) programs adopted an approach using programmatic assessment that is primarily reliant on frequent workplace-based assessments (WBAs) of multiple clinical encounters.1,2,3 The dual purposes of these WBAs, for both high stakes decisions on competence and to identify weaknesses and foster learning, creates a tension.4,5 It is particularly problematic where residents are also responsible for selecting the encounters on which they will be assessed; here residents preferentially (and understandably) select encounters they anticipate will support their promotion within their program.6,7 While we anticipated that frequent, “low-stakes” assessment would provide a wealth of feedback for learners, paradoxically it created gaps in feedback resulting in reduced utility.5,8,9,10

The gap is complicated by longstanding challenges supervising staff have in delivering constructive feedback. WBA requires assessors to document areas for improvement, a task faculty tend to avoid for a variety of reasons: perceived lack of supporting evidence for deficiencies, lack of knowledge surrounding what to document, anticipating an appeal or challenges, and lack of remediation options.11 Further, faculty may be less confident in reporting critical findings especially if their colleagues display ‘dove’-like assessment behaviours.12 Knowing that documented feedback contributes to progress and promotion decisions for residents adds further pressure to the faculty task. Alternative approaches to formulating constructive feedback that reliably capture learning needs without adding to summative assessment would complement WBA. Ideally, it would capture feedback across domains of competence and not be restricted to one or two—a limitation that can be seen with WBA.13,14,15,16,17

Faculty group review sessions and face-to-face assessor meetings increase identification of weaknesses in resident performance.12,18 Using a facilitator such as an experienced faculty member during the assessment process may also help improve the quality of feedback and identification of areas for growth.19 Additionally, interactive discussions promote identification of areas of improvement across the intrinsic CanMEDs roles.12 These findings point to an opportunity to use facilitated, confidential team-based assessment to capture constructive feedback across the CanMEDS roles. Specifically, this resulted in the creation of Feedback Fridays, an assessment initiative within the Queen’s University Core Internal Medicine residency program initiated in anticipation of these needs in programmatic assessment when CBME was introduced in 2017. In this research study, we aimed to explore in what ways Feedback Fridays contributed to formative assessment of Internal Medicine residents within our current model of competency-based training.

Method

Design

We adopted a qualitative approach to explore the nature of the narrative assessment data collected from ‘Feedback Friday’ in one Internal Medicine program.20 We used the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research checklist (COREQ)21 to ensure methodological rigor and guide our reporting of this study (Appendix A).

Context

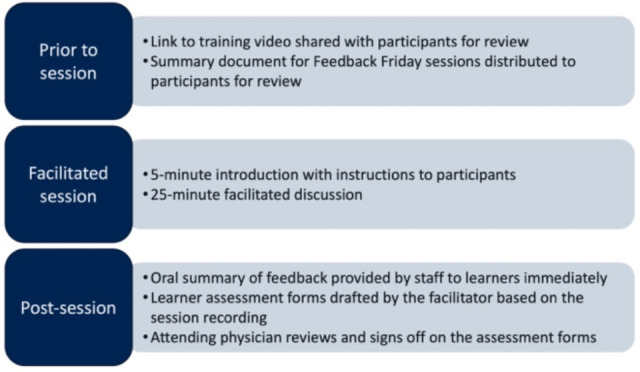

Our study occurred in the Core Internal Medicine program at Queen’s University. The 3-year program has approximately 20 residents per year. The program transitioned to CBME in July 2017 as part of an institutional transition. While on-service for Internal Medicine (IM), residents are assigned to clinical teaching units (CTUs) in four-week intervals where they remain with the same resident peers. The supervising attendings rotate every two weeks. Residents are encouraged to seek and initiate formal assessment through WBAs of directly observed, discrete clinical encounters with at least one assessment completed per week. Ideally the WBAs would be completed in person with the resident however, this is not always possible due to the constraints of the clinical workload. Additionally, residents also receive longitudinal assessment (using our “Periodic Performance Assessment” forms) that capture performance over a two-week period.22 An overview of the Feedback Friday sessions is provided below in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Overview of the Feedback Friday sessions.

The training program allocated each inpatient general medicine teaching team a 30-minute meeting every two weeks to gather assessment data from all team members through a confidential, facilitated, team discussion. Specifically, sessions aimed to collect data reflective of each resident’s clinical performance over the prior two weeks. Professional development was provided prior to beginning Feedback Fridays in the form of a YouTube video (https://youtu.be/OsRB3NfL00g) and a Feedback Friday summary document. The YouTube video provided participants in Feedback Friday an opportunity to review the components of quality feedback and ensure there was a shared mental model of the purpose and structure of sessions; the goal was to equip participants to provide feedback that was timely, specific, focused on improvement, and grounded in shared expectations.23 The Feedback Friday summary document described the descriptions of competence for each stage in the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada’s Competence by Design model24 to support the shared understanding of the feedback discussions for each learner participating in Feedback Fridays. Our Assessment Officer, trained in conducting the facilitated assessment sessions and not involved in directly assessing residents, facilitates these discussions. The entrustable professional activities (EPAs) for training guide the discussion, but the facilitator also explores and captures all emerging areas of feedback. As well, the facilitator instructs participants not to discuss feedback of a sensitive nature during meetings, but instead, provide such feedback directly to their staff physician. To ensure confidentiality, all residents at the same training level step out of meetings during discussion of their performance. The assessment officer collects and subsequently documents feedback from the sessions directly into longitudinal assessment forms. Additionally, the staff physician for the team provides oral feedback to residents immediately following meetings to alleviate resident anxiety related to confidential discussions. Importantly, the assessment data gathered and documented are used by residents and their advisors to support learning; the data collected is not used in decisions to award EPAs.

Sample

Participating in Feedback Friday was compulsory for all residents. However, the research study was optional. Residents were provided with consent forms at the beginning of the session. If participants did not want to consent, those facilitated assessment sessions were not going to be included in the analysis. Using convenience sampling, all participants from the Feedback Friday sessions were invited to have their assessment data included in the study. A total of 53 residents agreed to participate. The research component of this initiative was approved by Health Sciences and Affiliated Teaching Hospitals Research Ethics Board (File # 6021327).

Data collection

The program director developed the semi-structured protocol with input from the program’s Assessment Officer (Appendix B) for the facilitated Feedback Friday assessment sessions. The protocol focused discussion around the entrustable professional activities (EPAs) that aligned with the stage of training of each resident discussed. For example, questions were asked about how the resident performed when assessing and admitting patients to the hospital. Other questions focused on treatment of unstable patients, performing procedures, and communicating with team members (including allied health). Participants were also provided with the opportunity to give more open feedback identifying what the resident could work on and what they were doing well. Other questions revolved around opportunities to teach (both formal and informal), as well as management plans, discharge plans, and communicating with families. The facilitated assessment sessions were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Data analysis

The data we analyzed here were collected in the clinical workplace at the local hospital through the biweekly Feedback Friday meetings described below. We did not collect demographic data to ensure participant confidentiality. However, there was representation of residents across all three years of postgraduate training in IM, and both women and men trainees were included in the sample. We uploaded completed transcripts from the facilitated assessment sessions into NVivo (Version 12, QSR International, Melbourne Australia) for analysis. We then analyzed the transcripts thematically25 to identify patterns across the data following the six steps for thematic analysis including 1) Familiarizing ourselves with the data, 2) Generating initial codes, 3) Searching for themes, 4) Reviewing themes, 5) Defining and naming themes, and 6) Producing the report. Before starting the coding process, the researchers responsible for analyzing the data read through each transcript again to re-orient themselves with the data. Research team members with training and experience in qualitative research (H.B., R.O., and N.D.) independently coded the transcripts generating initial codes. The researchers then came together and discussed their coding line by line. An overall inter-coder agreement of 88% was calculated before discussion. This agreement level was calculated by adding the number of times that the researchers agreed on each coded segment divided by the total number segments coded and then multiplied by 100 to obtain the percentage reported above. The coders discussed the segments and names of codes until complete agreement was reached and there was shared meaning across all codes. This coding discussion resulted in a consensus-built codebook that was used by one researcher (H.B.) for the remainder of the coding process. This process is in alignment with guidelines for conducting intercoder reliability.26 Open coding was performed across each transcript. This consisted of reading sentence-by-sentence and assigning a code that captured the essence of each sentence or discussion segment. After each transcript was coded, the researchers searched for themes and collated the codes. Data sufficiency was evident given that the same patterns were being identified across transcripts and no new findings were reported after analyzing 17 of the transcripts. However, to ensure representation across participants, the researchers coded all 8 remaining transcripts. Similar codes were then grouped together into larger categories called subthemes. The same process was used to group similar subthemes together forming broader themes evident across the data. The analysis process was iterative with ongoing refinement of the code names and subtheme organization following discussion with the whole research team. Once preliminary themes had emerged, they were brought forward to the whole research team for interpretation and to ensure accurate representation of the data.

Reflexivity

Our research team engaged in reflexive discussions throughout the entire research process focused on challenging assumptions, identifying potential biases, and being aware of their positionality.27,28 D.T. designed the study. R.O. conducted recruitment and data collection. Two researchers lead the analysis process (H.B. and N.D). All members of the research team contributed to ongoing refinement of the themes and knowledge translation activities. D.T. is the program director with experience in medical education and education scholarship, and known to all participants. He did not participate in recruitment or in coding of the data to avoid introducing bias based on his position and role in designing the intervention. R.O. is the Program Assessment and Evaluation Officer and known to all of the participants. H.B. and N.D. are PhD trained mixed methodologists with extensive experience in educational scholarship. Further, H.B. specialized in assessment as part of her doctoral work and brings that lens to much of her scholarship. Both H.B. and N.D. are external to the IM program.

To maintain reflexivity, one researcher conducting the majority of the coding (H.B.) documented her ongoing thoughts, memos, and reflective thoughts on biases in a coding diary. Further, she also made note on emerging themes and her interpretations of the data. This process helped to facilitate an ongoing critical stance as a means of mitigating bias and ensuring accurate interpretations of the data.

Results

A total of 25 Feedback Friday sessions occurred during the study period in the 2017-2018 academic year. All 53 residents participating in these sessions consented and were included as participants in the research study. Each session consisted of 5-8 trainees plus the facilitator and assigned faculty member.

Our analysis revealed that CTU members focused their feedback within four main themes throughout the Feedback Friday sessions: Communication, Intrapersonal and Interpersonal Awareness, Leadership and Teamwork, and Learning Opportunities. An overview of the emergent themes is provided in Table 1 alongside affiliated subthemes. Additional quotations can be found in Appendix C and are organized according to theme and subtheme. Quotations are identified by the participants facilitated assessment session (FAS) number (e.g., focus group facilitated assessment session 4 is represented by FAS4).

Table 1.

Emergent themes and subthemes.

| Theme | Subthemes |

|---|---|

| Communication | Within team With patients and families |

| Intra- and Inter-personal awareness | Personal insight Disposition |

| Leadership and Teamwork | Support Team dynamic Delegation |

| Learning Opportunities | Teaching Missed opportunities |

Theme 1: Communication

The focus group facilitated assessment sessions frequently centred around the Communicator role both within the CTU team and beyond. Residents were quick to identify instances where their colleagues were clear, professional, and respectful in their communication. For example, one participant described effective communication as part of the handover process,

As far as transitions of care goes, she is very good at delivering handover and communicating active issues with people…She always makes a point of the two of us sitting down and talking about the patient who is coming out [of intensive care] so that I know what we are inheriting. (FAS19)

Sometimes participants directed the feedback towards communication with allied health professionals as mentioned by this participant when asked to describe how well a resident managed their communication, they shared

She makes an effort to go talk to them in person and that makes a difference. Today she was asking who the social worker was on the floor so that she could find her directly, and that helps in terms of making sure the patients have safe plans and they are discharged as soon as possible. (FAS14)

Other times the feedback about communication was in relation to families and patients. This participant described how a resident effectively communicated with a family member,

I have seen her do that with a couple of families in relation to patients who were discharged…. She couldn’t communicate with the patient and had to talk to the daughter. But the daughter was fully informed, and she informed her well about what might happen. (FAS 2)

Despite the many positive instances of effective communication, CTU members also provided some corrective feedback. For example, one member explained “...He has [a] great plan and he writes it down but it’s just [improving] the verbal communication of it in a clear and concise manner” (FAS 10). No matter the level of experience or training, all participants showed themselves capable of providing feedback on the Communicator role.

Theme 2: Intrapersonal and interpersonal awareness

Another common area of focus for feedback included personal insight and cognizance of the team disposition. At times, participants described strengths or areas for growth related to an individual’s insight. For example, this CTU member shared how a colleague gathers different perspectives,

He has a great attitude. And in terms of management plans he implements them to a certain degree and doesn't go beyond the point of no return. And before reaching that point, he looks for feedback. He asks for different thoughts and other ideas. (FAS22)

Many CTU members also commented on the perceived level of confidence and were quick to share when a colleague was confident. This participant elaborated further, “He has confidence and comfort level which is good and as a senior that is helpful” (FAS2) The feedback also was related to an individual’s disposition, which, when identified as a strength, included being approachable and friendly. This participant explained, “…She is very approachable and offers to help even when we don’t ask. She is very nice and friendly” (FAS14). The level of control, calmness, and empathy were also shared as examples of intra- and inter-personal disposition as described by this CTU member “His calmness and collectiveness carries him a long way. He doesn't get overwhelmed in [the emergency department]” (FAS13). However, members did provide constructive feedback around appropriate levels of confidence as described below:

I would say be careful with being too overconfident with the diagnosis. If you anchor too much on something you will lose sight of everything else.…if you are going to say you are 100% certain of something then you had better be 100% certain or else your credibility will go down a bit. (FAS20)

In conclusion, participants were quick to provide examples of resident awareness, both intrapersonal and interpersonal.

Theme 3: Leadership and teamwork

The third theme identified was leadership and teamwork as it related to support, team dynamics, and delegation. Support, at times, was in the form of a recommendation to take on more senior roles and responsibilities as stated by this participant, “I feel like he is good enough that he should start taking on the senior roles.... This last CTU block will be a good transition” (FAS25). Sometimes the feedback indicated that a resident required more support. Often the feedback revealed when teammates felt supported as mentioned by this participant,

One thing I appreciate is that I find he has been very supportive. Today he could tell that I was a little frazzled after a patient encounter and he said, ‘You know what, I am done with my list so why don’t I help you out with this next one’. And that is a great and supportive thing for a senior to do. (FAS2)

Sometimes the CTU team dynamics (the behavioural interactions among team members) were also discussed in the feedback process. For example, one resident shared how their colleague established good team dynamics, “He brings the team together and establishes a good team dynamic. I was pleased to have him [as part of the team] and he contributes very well to the medical student’s [working] environment” (FAS2). Lastly, participants provided feedback relating to leadership including delegating tasks as part of the Leader role. The ability to delegate by clarifying expectations was identified as a strength by many participants: “He does a good job of delegating tasks to make sure everyone knows what their role is and knows what they have to do for the day” (FAS19). However, the need to delegate was also identified as an area for growth for some residents as described below.

She has been super helpful with helping me navigate the list of our patients. I think it is important for her to transition from the R2 senior resident role to the R3 senior role. And so maybe step back a bit... she listed off her expectations to the team this morning which is our team because I am the R2 on the team. And so, it would be nice if she relinquished a bit of control there for the transition of the role and let me have the opportunity to grow more with the team… (FAS10)

The ability to maintain positive team dynamics, mentor colleagues, and effectively delegate were common areas of feedback for this theme.

Theme 4: Learning opportunities

The final theme identified from the facilitated assessment sessions aligned with teaching and missed learning opportunities. Many participants discussed instances of both formal and informal teaching opportunities. At times this was used to commend residents on their teaching as colleagues appreciated learning from each other. For example, this included instances of coaching as described by this participant, “He allowed us to take the lead on the physical exam. But he coached us through certain aspects of it and added the extra knowledge that he had” (FAS6). Some residents emphasized the need to plan for specific teaching time or to focus on more formal teaching: “...she does have a lot of clinical knowledge and so it would be nice from an R1 perspective if I could tap into that a bit more. She does a lot of impromptu teaching organically...” (FAS2).

Residents also provided examples where they felt that their colleagues had missed learning opportunities while on the CTU. Missed opportunities often related to experiences reviewing patients as the comment from this participant suggests ,”...there is a junior attending and our attending is very hands on. So, the residents are not so much running the list, more so the staff is. She hasn’t really had an opportunity to [lead rounds] yet” (FAS3). Additional areas that residents identified as needing more opportunities included being involved in formal family meetings and in communicating treatment options to patients and caregivers, and other active learning experiences within the team. Similar to the first subtheme, some of the examples related to teaching approaches where residents reported that they missed opportunities as explained by this CTU member,

He is a good teacher. But sometimes he is so excited to teach that when he asks a question, before everyone can formulate their response...then he blurts out the answer...it is because he loves it and is passionate about it...maybe just slowing it down a step would be nice. (FAS20)

Discussion

CBME’s emphasis on frequent, focused assessments of clinical tasks brings both intended and unanticipated consequences on learners. Despite increasing the overall volume of assessment data, WBA can paradoxically curtail constructive feedback and de-emphasize feedback on non-medical expert (the intrinsic) CanMEDS roles.9,14,16,17,29,30 Building on research showing benefits from facilitated, interactive, and group approaches to learner assessment,31,32 Feedback Friday was designed as a novel approach to collecting workplace-based performance data that includes additional perspectives, characterizes resident performance over a period of time, identifies areas for improvement, and brings more attention to competencies within the intrinsic CanMEDS roles. In consideration of the purpose of this study, our findings highlighted potential benefits; we showed that the approach could be a source of rich, narrative feedback for learners with content focused across four major themes: communication; intra- and inter-personal awareness; leadership and teamwork; and learning opportunities. The Health Advocate and Scholar roles were noticeably smaller components of the feedback and, as such, were not captured in overarching themes. These findings have important implications for personalized learning and programmatic assessment in CBME.

Professional development played a key role in the successes of Feedback Friday. Consistent with the literature,33,34 we emphasized development of a shared mental model amongst all participants, including goals, expectations, and norms of participation. We believe this set the stage for a successful implementation characterized by collection of rich, narrative feedback grounded in an established shared mental model for quality feedback.

Implementation also saw some challenges. One challenge in implementing the Feedback Friday initiative was its requirement that multiple physicians be in the same place at the same time. Consequently, there were times that Feedback Friday sessions had to be re-scheduled with delays in feedback. There was also uneasiness expressed by residents around the feedback conversations that happened without them. This improved significantly with implementation of attending physicians verbal feedback immediately following sessions.

In attempting to ground the approach for Feedback Fridays within programmatic assessment for CBME, we based the facilitator’s interview guide on Internal Medicine EPAs commonly performed on CTU. We expected discussion to naturally focus on task performance, potentially with a predominantly summative perspective; the facilitator, we surmised, would have to actively unpack competencies in the discussion. Instead, participants in Feedback Friday naturally provided a formative emphasis on clinical competencies and the intrinsic roles. This suggested that resident participants engaged in these sessions with a learning mindset35 and holistic perspective across physician roles. This stands in contrast to recent descriptions of the nature of resident engagement with WBA, which include an expressed lack of buy-in, being viewed as high stakes, and selectively seeking assessment opportunities from positive clinical encounters to support promotion,29,36,37,38 all of which are counterproductive to resident learning and development.

Our findings present significant opportunities for building learner-centredness into competency-based program design.(39) The rich, constructive feedback and focus on competencies provides critical substrate for residents to build personalized learning plans and engage with self-regulated learning. Further, the de-emphasis on summative assessment of EPAs relieves the tension that exists between the summative and formative goals of workplace-based assessment in CBME.40 For programs, this creates a safe space to develop and promote growth mindset culture during training, an important challenge in programmatic assessment in CBME. Our findings also have important implications for clinical faculty supervising trainees. The growing burden of assessment tasks for faculty supervising multiple learners on clinical rotations represents a major barrier for collecting rich, narrative feedback in CBME.41 Although faculty remained responsible for reviewing and signing off the rotation assessment forms, the facilitated approach used here relieved faculty of the work of collecting feedback and composing these narratives. This also promoted timely and accurate completion of documentation for learners. With the substantial increase in assessment load associated with CBME, this may be an important benefit that should be explored further.

There are important next steps including the need for a formal evaluation of the Feedback Friday initiative to gather perspectives from both the residents and the faculty. This could include understanding how feedback from the Feedback Friday sessions is integrated into the resident personal learning plans.

Limitations

Our study has a few limitations. This study was started within several months of launching the Feedback Friday initiative. The culture and mindset change needed to support students and residents participating in these dialogues was in its early stages. The landscape and environment were changing as we gathered the data. This likely influenced the nature of the feedback collected. Also, we initiated Feedback Friday in a single program in one department, at a single centre. Specifically, the initiative worked well on the CTU rotation. Additional work needs to be done to ensure our findings can be transferred to other contexts including other learning environments.

Conclusion

Feedback Fridays in the Core IM Program at Queen’s drew out difficult to capture rich, narrative feedback. Further the themes identified in the discussions focused primarily on the intrinsic CanMEDS roles—crucial assessment data that is complimentary to data gathered in WBAs emphasized by CBME. In this way, the facilitated, team-based approach to assessment used in Feedback Fridays may fill an important gap in programmatic assessment in CBME.

Appendix A. COREQ (COnsolidated criteria for REporting Qualitative research) Checklist

A checklist of items that should be included in reports of qualitative research. You must report the page number in your manuscript where you consider each of the items listed in this checklist. If you have not included this information, either revise your manuscript accordingly before submitting or note N/A

| Topic | Item No. | Guide Questions/Description | Reported on Page No. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Domain 1: Research team and reflexivity | |||

| Personal characteristics | |||

| Interviewer/facilitator | 1 | Which author/s conducted the interview or focus group? | P 4. |

| Credentials | 2 | What were the researcher’s credentials? E.g. PhD, MD | P 4. |

| Occupation | 3 | What was their occupation at the time of the study? | P 4. |

| Gender | 4 | Was the researcher male or female? | P 1. |

| Experience and training | 5 | What experience or training did the researcher have? | P 3. |

| Relationship with participants | |||

| Relationship established | 6 | Was a relationship established prior to study commencement? | P 3. |

| Participant knowledge of the interviewer |

7 | What did the participants know about the researcher? e.g. personal goals, reasons for doing the research | P 3. |

| Interviewer characteristics | 8 | What characteristics were reported about the inter viewer/facilitator? e.g. Bias, assumptions, reasons and interests in the research topic | P 4. |

| Domain 2: Study design | |||

| Theoretical framework | |||

| Methodological orientation and Theory | 9 | What methodological orientation was stated to underpin the study? e.g. grounded theory, discourse analysis, ethnography, phenomenology, content analysis | P. 2 |

| Participant selection | |||

| Sampling | 10 | How were participants selected? e.g. purposive, convenience, consecutive, snowball | P.3 |

| Method of approach | 11 | How were participants approached? e.g. face-to-face, telephone, mail, email | P.3 |

| Sample size | 12 | How many participants were in the study? | P 4. |

| Non-participation | 13 | How many people refused to participate or dropped out? Reasons? | P 4. |

| Setting | |||

| Setting of data collection | 14 | Where was the data collected? e.g. home, clinic, workplace | P 2. |

| Presence of non-participants | 15 | Was anyone else present besides the participants and researchers? | N/A |

| Description of sample | 16 | What are the important characteristics of the sample? e.g. demographic data, date | N/A |

| Data collection | |||

| Interview guide | 17 | Were questions, prompts, guides provided by the authors? Was it pilot tested? | P 3 & Appendix |

| Repeat interviews | 18 | Were repeat inter views carried out? If yes, how many? | N/A |

| Audio/visual recording | 19 | Did the research use audio or visual recording to collect the data? | P 3. |

| Field notes | 20 | Were field notes made during and/or after the inter view or focus group? | N/A |

| Duration | 21 | What was the duration of the inter views or focus group? | P 3. |

| Data saturation | 22 | Was data saturation discussed? | P 4. |

| Transcripts returned | 23 | Were transcripts returned to participants for comment and/or | N/A |

| Domain 3: analysis and findings | |||

| Data analysis | |||

| Number of data coders | 24 | How many data coders coded the data? | P 4. |

| Description of the coding tree | 25 | Did authors provide a description of the coding tree? | N/A |

| Derivation of themes | 26 | Were themes identified in advance or derived from the data? | P 4. |

| Software | 27 | What software, if applicable, was used to manage the data? | P 3-4. |

| Participant checking | 28 | Did participants provide feedback on the findings? | N/A |

| Reporting | |||

| Quotations presented | 29 | Were participant quotations presented to illustrate the themes/findings? Was each quotation identified? e.g. participant number |

P 5-6 & Appendix |

| Data and findings consistent | 30 | Was there consistency between the data presented and the findings? | N/A |

| Clarity of major themes | 31 | Were major themes clearly presented in the findings? | P 5-6 & Appendix |

| Clarity of minor themes | 32 | Is there a description of diverse cases or discussion of minor themes? | P 5-7 & Appendix |

Appendix B.

Feedback Friday Facilitator Instructions and Session Discussion Guide

Important points to make at the beginning

All feedback here is confidential, nothing leaves the room

If there is feedback you feed should be delivered confidentially, outside of a group setting, please make sure to speak with your attending privately to ensure this is captured. DO NOT talk about things you recognize as inappropriate for group discussion.

R2s and R3s – please provide a brief verbal summary of the feedback for the junior residents today

Attending – please provide a brief verbal summary of the feedback for the senior residents today.

Areas to Explore in Discussion

Starting with juniors – target is Foundations of Discipline level performance

Describe the strengths of the resident. Alternatively, what aspects of the resident’s clinical work role-models what junior learners should be doing.

- Any above and beyond moments?

Describe any additional things this resident could do that would make you feel more comfortable giving them more independence and responsibility?

- Better recognition of key features of presentations and synthesis of information in summarizing cases

- Greater independence/consistency in generating differentials and plans

- Able to recognize and fills knowledge gaps independently

- Better recognition of when they’re out of their depth

Describe any feedback you’ve heard from patients or allied health. Either complements or areas they could develop.

Senior Resident Discussion

Describe the strengths of the resident. Alternatively, what aspects of the resident’s clinical work role-models what senior learners should be.

For the attending – describe additional things this resident could do that would make you feel more comfortable giving them more independence and responsibility?

- Managing emergent situations

- Anticipating complications from disease or treatment

- Supervising junior learners

- Supporting patients and families in complicated situations

- Making safe, well thought-out discharge plans

For juniors, suggest 1-2 things this resident could adopt to improve.

Study Title: Team-based Assessment of Resident Performance: A Mixed Methods Study

Internal Medicine Clinical Training Unit weekly group assessment guide

Clinical Training Unit (CTU): (A) (B) (C) (D)

Block and rotation dates: _______________________________________

Participants’ names and roles or levels of training:

Attending physician: _______________________________________

PGY1: ____________________________________________

PGY2: ____________________________________________

PGY3: ____________________________________________

PGY4: ____________________________________________

Assessment sessions are semi-structured; questions will be adapted to the flow of discussion

Describe how the resident is performing for the professional activities expected at their stage.

Describe any barriers you perceive that may be preventing the resident from achieving performance goals?

Can you give examples of cases when the resident has not performed to the expected standard?

Describe some particular strengths the resident demonstrates that should be reinforced.

Please provide some of your suggestions for this resident to improve.

For residents in the group that we just assessed, do you have any additional observations?

Appendix C. Additional quotations

| Theme | Additional Quotations |

|---|---|

| Communication | “He seems to be helpful to the medical students with answering questions and that.” (FAS4) |

| “I do have one thing, it just hit me. Sometimes when I have been …I don’t know where this is directed but sometimes when I have been on call I have been called about patients who are unstable who I was never told about. And so, I will be called and they will say, this patient has respiratory distress and is acutely unstable.” (FAS1) | |

| “I was with her once when we were talking to someone and he was confused and she was on the phone with his wife. And she was really good and kept her updated and she was cognizant of the patient and the family and the plan.” (FAS2) | |

| “She outlines care plans very clearly when we do handover and so that is helpful.” (FAS14) | |

| Intra- and inter-personal awareness | “She is my R3 on the team. She is approachable and is always around. If I need any questions or if I have concerns then I can just ask her.” (FAS3) |

| “So, when I filled out the feedback I said, be aware of recognition of patients who need increased monitoring.” (FAS5) | |

| “…and in general she has a very friendly disposition.” (FAS14) | |

| “and confidence is an issue sometimes. But most of the time I agree with what she says and so just to have some confidence.” (FAS18) | |

| Leadership and Teamwork | “He does so much that you feel like you don’t have enough to do. He is really good.” (FAS25) |

| “He lends morale to the team and is a fun guy to be around.” (FAS2) | |

| “A lot of R2’s do that because they want to be hands on and so he needs to learn to delegate a bit better.” (FAS25) | |

| “I know he can do it and he can take care of everything for the patients. But he has a really strong team with him and so taking more of a step back if you have time. And so, delegate things and keep that bird’s eye view and that fall back system that he needs a senior resident. So that is the feedback that I gave him.” (FAS6) | |

| Learning Opportunities | “and maybe do some informal teaching sessions with the students if he has time.” (FAS4) |

| “So, the R3 role certainly allows itself towards teaching but it is part of any senior resident’s job description to be working on educating you guys. And so that would be something that she could do more of. I recognize that having a full days’ worth of Davies 4 patients does not allow much time, but I don’t know if there will be a push to carve out time for teaching. If you scheduled then it would be more likely to happen.” (FAS19) | |

| “And then really good at explaining the answer and/or getting you to think of something and then saying why it is wrong.” (FAS5) | |

| “We are surprisingly low on procedures for this block.” (FAS19) |

Funding Statement

Funding

Research supported by the SEAMO Endowed Scholarship and Education Fund

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Edited by

Christina St. Onge (senior section editor); Marcel D’Eon (editor-in-chief)

References

- 1.Schuwirth L, Ash J. Assessing tomorrow's learners: in competency-based education only a radically different holistic method of assessment will work. Six things we could forget. Med Teach. 2013;35(7):555-9. 10.3109/0142159X.2013.787140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schuwirth L, Valentine N, Dilena P. An application of programmatic assessment for learning (PAL) system for general practice training. GMS J Med Educ. 2017;34(5):Doc56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van der Vleuten CP, Schuwirth LW, Driessen EW, et al. A model for programmatic assessment fit for purpose. Med Teach. 2012;34(3):205-14. 10.3109/0142159X.2012.652239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Branfield Day L, Miles A, Ginsburg S, Melvin L. Resident perceptions of assessment and feedback in competency-based medical education: a focus group study of one internal medicine residency program. Acad Med. 2020;95(11):1712-7. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Watling CJ, Ginsburg S. Assessment, feedback and the alchemy of learning. Med Educ. 2019;53(1):76-85. 10.1111/medu.13645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gaunt A, Patel A, Rusius V, Royle TJ, Markham DH, Pawlikowska T. 'Playing the game': How do surgical trainees seek feedback using workplace-based assessment? Med Educ. 2017;51(9):953-62. 10.1111/medu.13380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gaunt A, Patel A, Fallis S, et al. Surgical trainee feedback-seeking behavior in the context of workplace-based assessment in clinical settings. Acad Med. 2017;92(6):827-34. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gaunt A, Markham DH, Pawlikowska TRB. Exploring the role of self-motives in postgraduate trainees' feedback-seeking behavior in the clinical workplace: a multicenter study of workplace-based assessments from the United Kingdom. Acad Med. 2018;93(10):1576-83. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gaunt A, Patel A, Fallis S, et al. Surgical trainee feedback-seeking behavior in the context of workplace-based assessment in clinical settings. Acad Med. 2017;92(6):827-34. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Teunissen PW, Stapel DA, van der Vleuten C, Scherpbier A, Boor K, Scheele F. Who wants feedback? An investigation of the variables influencing residents' feedback-seeking behavior in relation to night shifts. Acad Med. 2009;84(7):910-7. 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181a858ad [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dudek NL, Marks MB, Regehr G. Failure to fail: the perspectives of clinical supervisors. Acad Med. 2005;80(10 Suppl):S84-7. 10.1097/00001888-200510001-00023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schwind CJ, Williams RG, Boehler ML, Dunnington GL. Do individual attendings' post-rotation performance ratings detect residents' clinical performance deficiencies? Acad Med. 2004;79(5):453-7. 10.1097/00001888-200405000-00016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bandiera G, Lendrum D. Daily encounter cards facilitate competency-based feedback while leniency bias persists. Cjem. 2008;10(1):44-50. 10.1017/S1481803500010009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ginsburg S, Gold W, Cavalcanti RB, Kurabi B, McDonald-Blumer H. Competencies “plus”: the nature of written comments on internal medicine residents' evaluation forms. Acad Med. 2011;86(10):S30-S4. 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31822a6d92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chou S, Cole G, McLaughlin K, Lockyer J. CanMEDS evaluation in Canadian postgraduate training programmes: tools used and programme director satisfaction. Med Educ. 2008;42:879-86. 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2008.03111.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rida T-Z, Dubois D, Hui Y, Ghatalia J, McConnell M, LaDonna K, editors. Assessment of CanMEDS competencies in work-based assessment: challenges and lessons learned. 2020. CAS Annual Meeting. [Google Scholar]

- 17.McConnell M, Sherbino J, Chan TM. Mind the gap: the prospects of missing data. J Grad Med Ed. 2016;8(5):708-12. 10.4300/JGME-D-16-00142.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hemmer PA, Hawkins R, Jackson JL, Pangaro LN. Assessing how well three evaluation methods detect deficiencies in medical students' professionalism in two settings of an internal medicine clerkship. Acad Med. 2000;75(2):167-73. 10.1097/00001888-200002000-00016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sargeant J, Lockyer J, Mann K, et al. Facilitated reflective performance feedback: developing an evidence-and theory-based model that builds relationship, explores reactions and content, and coaches for performance change (R2C2). Acad Med. 2015;90(12):1698-706. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yin R. Case study research and applications: design and methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349-57. 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McEwen LA EA, Chamberlain S, Taylor D. Queen's Periodic Performance assessments: capturing performance information beyond single observations in CBME Contexts. 2nd World Summit on CBME; Basel, Switzerland: 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taylor DR. Feedback Friday Intro [Video]. 2017. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OsRB3NfL00g&t=7s [Accessed 2024/02/05]

- 24.Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada . Competence by Design: Canada's model for competency-based medical education 2022. Available from: https://www.royalcollege.ca/rcsite/cbd/competence-by-design-cbd-e.

- 25.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psych. 2006;3(2):77-101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cofie N, Braund H, Dalgarno N. Eight ways to get a grip on intercoder reliability using qualitative-based measures. Can Med Ed J. 2022. 10.36834/cmej.72504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barry CA, Britten N, Barber N, Bradley C, Stevenson F. Using reflexivity to optimize teamwork in qualitative research. Qual Health Res. 1999;9(1):26-44. 10.1177/104973299129121677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Palaganas EC, Sanchez MC, Molintas VP, Caricativo RD. Reflexivity in qualitative research: a journey of learning. Qual Rep. 2017;22(2). 10.46743/2160-3715/2017.2552 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Day LB, Miles A, Ginsburg S, Melvin L. Resident perceptions of assessment and feedback in competency-based medical education: a focus group study of one internal medicine residency program. Acad Med. 2020;95(11):1712-7. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Watling CJ, Ginsburg S. Assessment, feedback and the alchemy of learning. Med Educ. 2019;53(1):76-85. 10.1111/medu.13645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ashenafi MM. Peer-assessment in higher education-twenty-first century practices, challenges and the way forward. Assess Eval High Educ. 2017;42(2):226-51. 10.1080/02602938.2015.1100711 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wanner T, Palmer E. Formative self-and peer assessment for improved student learning: the crucial factors of design, teacher participation and feedback. Assess Eval High Educ. 2018;43(7):1032-47. 10.1080/02602938.2018.1427698 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hawkins RE, Welcher CM, Holmboe ES, et al. Implementation of competency-based medical education: are we addressing the concerns and challenges? Med Educ. 2015;49(11):1086-102. 10.1111/medu.12831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sirianni G, Glover Takahashi S, Myers J. Taking stock of what is known about faculty development in competency-based medical education: a scoping review paper. Med Teach. 2020;42(8):909-15. 10.1080/0142159X.2020.1763285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Richardson D, Kinnear B, Hauer KE, et al. Growth mindset in competency-based medical education. Med Teach. 2021;43(7):751-7. 10.1080/0142159X.2021.1928036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Young JQ, Sugarman R, Schwartz J, O'Sullivan PS. Faculty and resident engagement with a workplace-based assessment tool: use of implementation science to explore enablers and barriers. Acad Med. 2020;95(12):1937-44. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Massie J, Ali JM. Workplace-based assessment: a review of user perceptions and strategies to address the identified shortcomings. Advan Health Sci Ed. 2016;21(2):455-73. 10.1007/s10459-015-9614-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Braund H, Dalgarno N, McEwen L, Egan R, Reid M-A, Baxter S. Involving ophthalmology departmental stakeholders in developing workplace-based assessment tools. Can J Ophthalmol. 2019;54(5):590-600. 10.1016/j.jcjo.2019.01.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Frank JR, Snell LS, Cate OT, et al. Competency-based medical education: theory to practice. Med Teach. 2010;32(8):638-45. 10.3109/0142159X.2010.501190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Govaerts MJ, van der Vleuten CP, Holmboe ES. Managing tensions in assessment: moving beyond either-or thinking. Med Educ. 2019;53(1):64-75. 10.1111/medu.13656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cheung K, Rogoza C, Chung AD, Kwan BYM. Analyzing the administrative burden of competency based medical education. Can Assoc Radiol J 2021:8465371211038963. 10.1177/08465371211038963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]