Abstract

PhoB is the response regulator of the Pho regulon. It is composed of two distinct domains, an N-terminal receiver domain and a C-terminal output domain that binds DNA and interacts with ς70 to activate transcription of the Pho regulon. Phosphorylation of the receiver domain is required for activation of the protein. The mechanism of activation by phosphorylation has not yet been determined. To better understand the function of the receiver domain in controlling the activity of the output domain, a direct comparison was made between unphosphorylated PhoB and its solitary DNA-binding domain (PhoBDBD) for DNA binding and transcriptional activation. Using fluorescence anisotropy, it was found that PhoBDBD bound to the pho box with an affinity seven times greater than that of unphosphorylated PhoB. It was also found that PhoBDBD was better able to activate transcription than the full-length, unmodified protein. We conclude that the unphosphorylated receiver domain of PhoB silences the activity of its output domain. These results suggest that upon phosphorylation of the receiver domain of PhoB, the inhibition placed upon the output domain is relieved by a conformational change that alters interactions between the unphosphorylated receiver domain and the output domain.

The ability to sense and respond to changing environmental conditions by genetic regulatory systems is an essential feature that enables bacteria to survive and adapt to numerous stresses. One way bacteria sense and respond to changing environments is through the use of two-component regulatory systems (9). In their simplest forms, two-component systems consist of histidine kinases and response regulators (21, 26). Histidine kinases transduce environmental cues into intracellular signals by interacting with and modifying response regulator proteins. Histidine kinases contain conserved catalytic (CA) and dimerization and histidine phosphorylation (DHp) domains (4). The DHp domain donates phosphate from a histidine residue to a universally conserved aspartate residue located within the response regulator. Phosphorylation of response regulators alters their activity, thereby allowing these proteins to function as phosphorylation-based biochemical switches (21, 26). Most response regulators consist of multiple domains: an N-terminal receiver domain that contains the site of phosphorylation and a C-terminal output domain that often binds DNA and activates transcription (28).

In Escherichia coli, the adaptive response to limiting phosphate is regulated by a two-component signal transduction system (27, 30). PhoB is the response regulator, and PhoR is the histidine kinase. PhoR is a transmembrane protein that modulates the activity of PhoB by promoting specific phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of PhoB in response to the phosphate signal (14–16). PhoB binds to specific DNA sequences and interacts with the ς70 subunit of RNA polymerase to control the transcription of more than 30 genes that comprise the Pho regulon (10, 24). This regulon includes operons and genes whose products are involved in phosphorous uptake and metabolism (30). All Pho regulon genes are preceded by a promoter that contains an upstream activation site in place of the −35 sequence termed the pho box (13). The pho box is composed of two 7-bp direct repeats with a conserved consensus sequence of CTGTCAT separated by a 4-bp AT-rich spacer region. The occurrence of a 7-bp repeat every 11 bp may allow multiple phospho-PhoB molecules to assemble on the same surface of the helix. Expression of the Pho regulon is inhibited when environmental Pi is in excess and activated when Pi is limiting (29).

Recent structural studies regarding the individual domains of PhoB have greatly contributed to the understanding of this protein (20, 25). The crystal structure of the receiver domain of PhoB has revealed that, like other response regulators, its structure consists of a doubly wound α/β fold (25). The C-terminal domain of PhoB belongs to the winged-helix-turn-helix family of transcription factors (17). The three-dimensional nuclear magnetic resonance structure of this DNA-binding domain (DBD) has also recently been solved (20). Notwithstanding this new structural information, how the individual domains interact in the functional protein is still not known.

In this study, we provide information about the ground state of PhoB, before it is activated. This information provides a framework of what phosphorylation accomplishes when the protein is activated. We present data that demonstrate that in its unphosphorylated state, the receiver domain of PhoB interferes with the DBD and its ability to activate transcription.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

The following E. coli strains were used to perform the experiments in this study. BW24249 [lacIq rrnBT14 ΔlacZWJ16 ΔphoBR580 ΔcreABCD154 hsdR514 Δ(pta ackA hisQ hisP)TA3516 phn(EcoB) ΔaraBADAH33 ΔrhaBADLD78 uidA(ΔMluI)::pir+ rpoS(Am) endABT333 galU95 recA1] was used to reduce the probability that PhoB could be phosphorylated during in vivo experiments and was kindly supplied by Barry L. Wanner (6). Transformation of BW24249 with pBAD-PhoB and pBAD-PhoBDBD created strains DWE1001 and DWE1002, respectively. TOP10 [F− mcrA Δ(mrr-hsdRMS-mcrBC) φ80lacZΔM15 ΔlacX74 recA1 deoR araD139 Δ(ara-leu)7697 galU galK rpsL (Strr) endA1 nupG] (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.) was used for general cloning and to study expression of PCR products. BL21(DE3) pLysS [B F− dcm ompT hsdS(rB− mB−) gal λ(DE3) (pLysS Camr)] (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) cells were used to study the overexpression of PhoB. E. coli strains were grown in rich medium (Luria-Bertani [LB]) which was supplemented with ampicillin (100 μg/ml) when appropriate.

Plasmid construction.

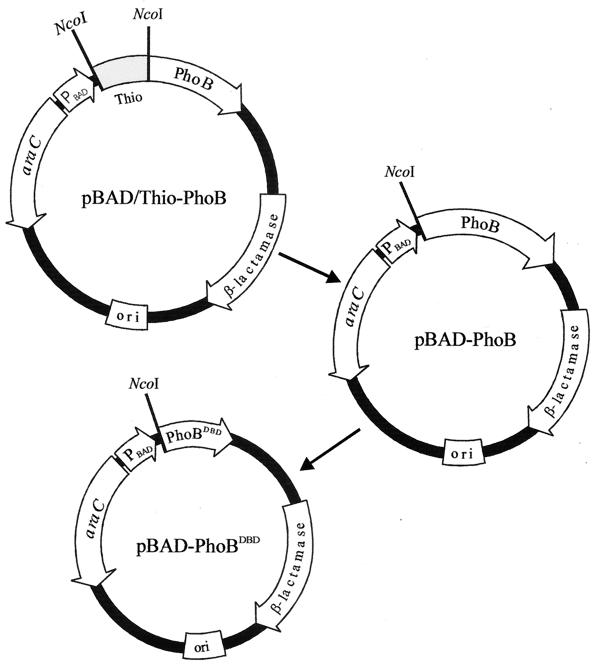

The linearized plasmid pBAD/Thio-TOPO (Invitrogen), which contains single 3′-thymidine overhangs, was used for cloning a PCR product that contained the phoB gene and which contained an NcoI site in frame with the start codon (see Fig. 1). The resulting plasmid was called pBAD/Thio-PhoB. All synthetic oligonucleotides used in this study were purchased from Life Technologies (Rockville, Md.) and are listed in Table 1. Oligonucleotides 1 and 2 were used to perform the PCR of PhoB from the chromosome. A NcoI digest was used to delete the thioredoxin moiety from the plasmid. The digested plasmid was then ligated using T4 DNA ligase to create plasmid pBAD-PhoB. To create a deletion of the receiver domain of PhoB, inverse PCR, using oligonucleotides 3 and 4, was performed on pBAD-PhoB, deleting amino acids 4 to 124, thereby creating pBAD-PhoBDBD. EcoRI sites at the 5′ ends of the primers allowed for the digestion of the linear PCR product with EcoRI and its subsequent ligation using T4 DNA ligase. The insertion of the EcoRI site into the deleted portion resulted in the introduction of a glutamate and a phenylalanine residue into the protein. PhoBDBD therefore consists of residues 1 to 3 of PhoB, followed by Glu-Phe, followed by residues 125 to 229. The araBAD promoter drives expression of the cloned products from these plasmids. The araC gene product is encoded on the parent vector and both positively and negatively regulates expression from this promoter.

FIG. 1.

Construction scheme for plasmids pBAD/Thio-PhoB, pBAD-PhoB, and pBAD-PhoBDBD. A chromosomal PCR product of phoB was cloned in frame into the pBAD/Thio-TOPO TA cloning vector (Invitrogen) to form plasmid pBAD/Thio-PhoB. pBAD/Thio-PhoB was then digested with NcoI and ligated to form pBAD-PhoB. Inverse PCR was performed on pBAD-PhoB using primers that contained in-frame EcoRI sites and which deleted the receiver domain of PhoB. This PCR product was then digested with EcoRI and ligated to form pBAD-PhoBDBD.

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotides used in this study

| Oligonucleotide | Sequencea |

|---|---|

| 1 | 5′-GCCATGGGGAGACGTATTCTGGTCGTAGAAGATG-3′ |

| 2 | 5′-TTAAAAGCGGGTTGAAAAACGATATCC-3′ |

| 3 | 5′-CGCGAATTCATGGCGGTGGAAGAGGTGATTGAG-3′ |

| 4 | 5′-CGCGAATTCTCTCCCCATGGGTATGTATATCTC-3′ |

| 5 | 5′-GCAGCTGTCATATATCTGTCATGCTCC C |

| 3′-GTCGACAGTATATAGACAGTACGACC |

The underlined bases indicate restriction enzyme sites. The regions in bold type represent a single copy of the pho box.

Fluorescence anisotropy measurements.

Anisotropy measurements were performed at 21°C in buffer containing 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.2), 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.05% Triton X-100, 10% glycerol, and 1 nM 5′-fluorescein-labeled oligonucleotide 5 by the addition of sequential amounts of protein to the reaction mixture. Preliminary experiments indicated that the inclusion of poly(dI-dC) did not affect the binding curves and was thus not included in the binding reaction mixtures. Protein concentrations were determined using the Bio-Rad Protein Assay (Richmond, Calif.). The 5′-fluorescein-labeled oligonucleotide forms a double-stranded hairpin structure containing a single consensus pho box. The labeled DNA was purified by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) to ensure removal of excess fluorescein. The oligonucleotide was heated to 95°C for 10 min and allowed to cool at 25°C overnight. The labeled oligonucleotide was excited at 487 nm, and emission was measured at 525 nm on a Quanta-Master PTI fluorescence instrument (South Brunswick, N.J.) configured in the L format. Three measurements were taken on each sample for 30 s, and the values were averaged to obtain each data point. Binding data were fit using nonlinear regression to a standard single-site binding equation: y = ([L] × Cap)(KD + [L]), where y is the anisotropy value, Cap is the total change in anisotropy, [L] is the concentration of protein, and KD is the dissociation constant of the ligand.

BAP assay.

E. coli DWE1001 and DWE1002 were grown overnight in 100 ml of LB broth in the presence of ampicillin (100 μg/ml) and 0.2% arabinose. In duplicate cultures, arabinose was omitted and glucose was added to a concentration of 20 mM to repress expression from the araBAD promoter. Three 1-ml samples were taken from each flask and harvested by centrifugation. The cells were resuspended in 1 ml of 1 M Tris-HCl (pH 8.2). Two drops of chloroform and 1 drop of 0.1% (wt/vol) sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) were added to each sample, which was then mixed vigorously for 1 min. Cells (500 μl) were mixed with 400 μl of 1 M Tris-HCl (pH 8.2) and 100 μl of 20 mM para-nitrophenylphosphate. The reaction mixture was incubated at 37°C until a yellow color was observed at which time 400 μl of 1 M KH2PO4 was added to stop the reaction. Arbitrary bacterial alkaline phosphatase (BAP) units were calculated using the following equation: BAP units = (OD420 × 2000)/(OD600 × time). OD420 is the absorbance of the reaction at 420 nm after the addition of KH2PO4. OD600 is the absorbance of the bacterial culture (grown overnight) at 600 nm. Time is measured in minutes.

Overexpression and purification of PhoB and PhoBDBD.

PhoB was purified as described previously (18). PhoBDBD was purified by growing DWE1002 overnight in LB broth containing 20 mM glucose to repress expression of PhoBDBD. The overnight culture was used to inoculate 4 liters of LB broth containing 0.002% arabinose, and these cultures were grown overnight at 37°C. Cells were harvested by centrifugation and resuspended in 25 ml of buffer A (25 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.2], 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA). Sonic disruption for 3 to 5 min on ice was used to disrupt the cells followed by centrifugation to remove cell debris. Following an initial 50% saturation ammonium sulfate cut, in which PhoBDBD remained soluble, PhoBDBD was precipitated with 70% saturated ammonium sulfate. The protein pellet was dissolved in buffer A, and the solution was then dialyzed against buffer A overnight at 4°C. PhoBDBD was further purified using a Biologic System (Bio-Rad) by loading the sample onto a phosphocellulose column and eluting the protein with a linear gradient of buffer B (25 mM Tris-HCl, 1 M NaCl, 1 mM EDTA [pH 7.2]). PhoBDBD was pooled from the peak fractions, dialyzed against buffer A, and further purified on a Bio-Rad Q2 column equilibrated in buffer A (pH 8.0). PhoBDBD did not bind to the column and was collected in the flowthrough fraction. The purity of PhoBDBD was verified by SDS-PAGE and was estimated to be at least 90%.

Western blot.

E. coli DWE1001 and DWE1002 were grown as described above for the BAP assay. The cells were harvested by centrifugation and resuspended in 5 ml of buffer A. The cells were then disrupted with zirconium beads in a Minibeadbeater (BioSpec, Bartlesville, Okla.). Equivalent amounts of cell extracts were separated by SDS-PAGE and blotted onto nitrocellulose membranes, and PhoB was visualized using the Immun-Star Chemiluminescent Protein Detection System (Bio-Rad). To determine the relative amount of PhoB or PhoBDBD in each lane, the bands were analyzed by film densitometry using an AlphaImager 2000 (Alpha Innotech Corporation, San Leandro, Calif.). To determine the amount of PhoB or PhoBDBD in the previous experiments, selected samples were run on duplicate gels that contained known amounts of PhoB or PhoBDBD and analyzed as described above.

RESULTS

To better understand the role of the receiver domain of PhoB in controlling the function of its DBD, experiments were conducted to compare unphosphorylated PhoB to its solitary DBD with regards to DNA binding and transcriptional activation. Purified proteins were used for in vitro DNA-binding experiments. For in vivo transcriptional activation experiments, plasmids that expressed either full-length PhoB or its DBD under the control of the regulatable arabinose promoter were constructed (Fig. 1).

Equilibrium binding of PhoB and PhoBDBD to a canonical pho box.

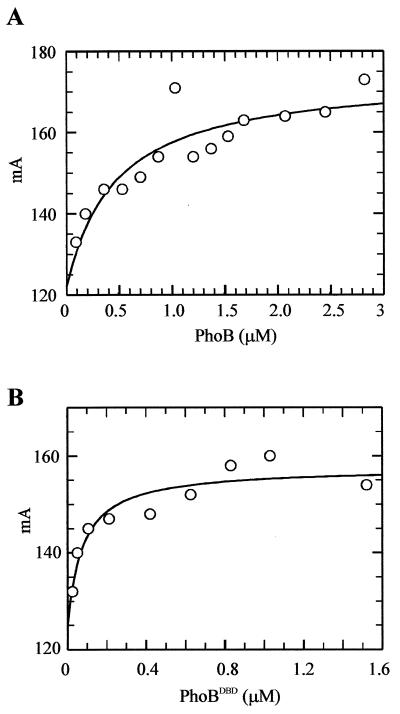

It had previously been demonstrated by DNase I protection and by band shift experiments that PhoB binds to a DNA sequence termed the pho box (12, 18). Quantitative band shift experiments indicated that unphosphorylated PhoB bound to a single pho box with an apparent KD of approximately 4 μM (18). Since band shift assays do not measure binding under equilibrium conditions, fluorescence anisotropy was chosen to examine DNA binding under equilibrium conditions. This technique has been used to examine DNA binding of several other response regulators (7, 23). A fluorescein-labeled, 50-bp oligonucleotide was designed to form a hairpin structure that contained a single consensus pho box (8). As shown in Fig. 2, the fluorescence anisotropy of the target DNA increased with increasing amounts of PhoB or PhoBDBD, indicating that both proteins bound to this DNA sample. We evaluated only the binding data from samples below 4 μM PhoB or PhoBDBD because above this concentration, the anisotropy increased linearly in a nonspecific manner (data not shown). Results from binding assays showed that PhoB bound to the consensus pho box with a KD of 440 ± 110 nM (Fig. 2A). This value represents the average ± standard deviation (SD) of five trials. In contrast, PhoBDBD bound with a KD of 63 ± 19 nM (average ± SD of three trials) (Fig. 2B). These two KD values differed significantly (P < 0.001; t test). These data show that PhoBDBD binds to its target DNA sequence with an affinity of about seven times that of the full-length protein. The results suggest that the unphosphorylated receiver domain of PhoB inhibits the DNA-binding activity of its output domain and that one role of phosphorylation of the receiver domain is to relieve the inhibition imposed on the output domain.

FIG. 2.

Fluorescence anisotropy measurements of DNA binding. (A) A representative binding curve for unphosphorylated PhoB showing binding to the consensus pho box. Each data point graphed represents an average of three readings of the same sample. Millianisotropy units (mA) are shown along the y axis. The concentration of PhoB is shown along the x axis. Unphosphorylated PhoB bound to the consensus pho box with a KD of 440 ± 110 nM. This value was derived from the average of five separate binding curves ± SD of the data. (B) A representative binding curve for PhoBDBD. This protein bound to the consensus pho box with a KD of 63 ± 19 nM. This value was calculated from the average of three separate binding curves ± SD of the data.

Transcriptional activation by PhoB and PhoBDBD.

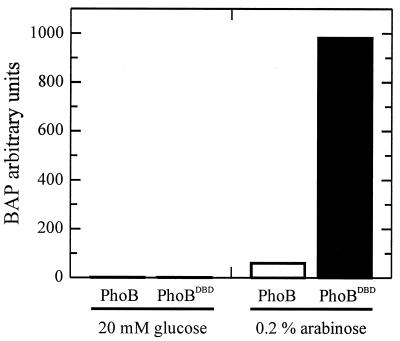

To compare the in vivo activity of unphosphorylated PhoB to PhoBDBD, pBAD-PhoB and pBAD-PhoBDBD were transformed into E. coli BW24249, a strain deficient in phosphorylation of PhoB, to create strains DWE1001 and DWE1002, respectively. PhoB and PhoBDBD were transcribed from the araBAD promoter. The ability of each protein to activate transcription was determined by measuring the relative amounts of BAP that were produced upon full induction. BAP is encoded by the phoA gene and is a member of the Pho regulon.

E. coli DWE1001 and DWE1002 cells were grown overnight in LB broth containing 0.2% arabinose, and BAP assays were performed (Fig. 3). Very low levels of BAP were detected when arabinose was omitted and glucose was included (to stimulate catabolite repression) in the growth media. However, when arabinose was included, thereby increasing the cellular concentrations of PhoB or PhoBDBD, the amounts of BAP also increased. It is apparent that under identical induction levels, PhoBDBD activates transcription of the phoA gene to a much greater extent than unphosphorylated, full-length PhoB. These data also support the idea that the receiver domain of PhoB, in its unphosphorylated form, inhibits the output function of the DBD. In these experiments, instead of measuring DNA binding directly, it was the transcriptional activation function of the DBD that was measured. This function may reflect DNA binding, DNA bending, or interactions with RNA polymerase.

FIG. 3.

Transcriptional activation functions of PhoB and PhoBDBD. The black bars represent the BAP activity produced in the presence of PhoBDBD, and the white bars represent the amounts produced in the presence of PhoB. The arbitrary BAP units are shown along the y axis. Each bar is an average of three separate samples taken from the same 100-ml culture grown overnight.

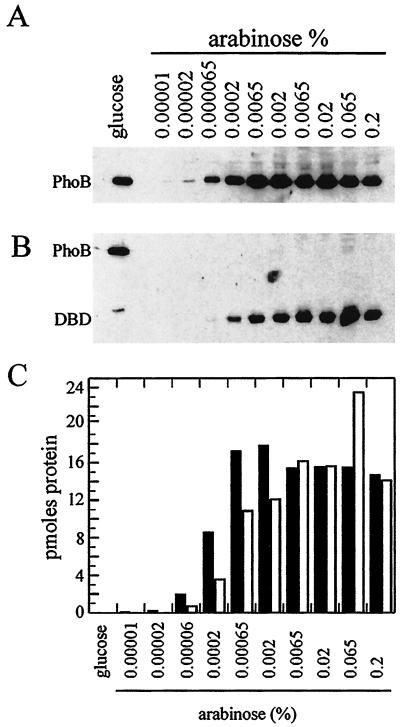

To ensure that the differences in phoA expression in E. coli DWE1001 and DWE1002 reflected the transcriptional activation function of PhoB and PhoBDBD, respectively, and were not simply due to different steady-state levels of PhoB or PhoBDBD, the cellular concentrations of these two proteins were compared using Western blot analysis. Samples were harvested from cultures grown overnight in various concentrations of arabinose, and protein concentrations were determined. Equivalent amounts of protein were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes, and probed with polyclonal PhoB antisera (Fig. 4A and B). The amounts of PhoB and PhoBDBD were estimated on each blot by comparing the intensities of bands on gels containing known amounts of PhoB or PhoBDBD (Fig. 4C). These data indicate that when 0.2% arabinose was included in the growth media, the phoB and phoBDBD genes were fully induced and the protein concentrations of PhoB and PhoBDBD in the experimental cells were nearly identical.

FIG. 4.

Quantitation of PhoB and PhoBDBD in E. coli DWE1001 and DWE1002. (A and B) Equivalent amounts of cell protein (5 μg) were separated by SDS-PAGE and blotted onto nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were probed with rabbit anti-PhoB sera, and PhoB was detected using an AP-conjugated anti-rabbit antibody using a chemiluminescence detection system. The blots were then exposed to X-ray film for 1-, 5-, and 15-min intervals to bracket the exposures within the linear range of the film. The bands were then analyzed with a densitometer and compared to known standards of PhoB or PhoBDBD. (C) Bar graph showing protein amounts for PhoB (white bars) and PhoBDBD (black bars).

DISCUSSION

We have measured the DNA-binding characteristics of PhoB and PhoBDBD using fluorescence anisotropy. The results from these experiments demonstrate that PhoBDBD binds more tightly to pho box DNA than does unphosphorylated PhoB. In addition, data from in vivo experiments examining the ability of these two proteins to activate transcription of the phoA gene show that the isolated DBD is a better transcriptional activator than full-length, unphosphorylated PhoB. Combined, results from both experiments provide evidence, that in the native protein, the unphosphorylated receiver domain of PhoB interacts with and inhibits the functions of its output domain. These conclusions are similar to those for the nitrate response regulator NarL, which were derived from its crystal structure. In its unphosphorylated form, the C-terminal domain of NarL is turned against the receiver domain in a manner that inhibits DNA binding (2). Negative regulation of output domain function is also observed with the closely related response regulator, OmpR (1). Unphosphorylated OmpR also binds DNA with a lower affinity than that of the phosphorylated protein. Another example of this type of negative regulation is observed with CheB in which its unphosphorylated receiver domain inhibits the methylesterase activity of its C-terminal output domain (11). It should be noted that not all response regulators control their output domains through inhibitory interactions. Positive control of an output domain has been demonstrated for the NtrC protein (31).

One simple explanation of these results is that the receiver domain blocks, through steric interactions, the DNA-binding and ς70 interaction functions of the DBD. Equally likely is the possibility that the unphosphorylated receiver domain interacts with the DBD to hold it in an inactive conformation. In either case, phosphorylation of the receiver domain must trigger conformational changes that lead to activation. In the first case, the conformational change would result in a rotation or displacement of the receiver domain in relation to the DBD that would provide access of this domain to DNA and RNA polymerase. In the second possibility, the conformational change would be transmitted across the domain interface to the DBD and result in an active structure. It has previously been demonstrated that PhoB forms a dimer upon phosphorylation (5, 18). The experiments reported by Fiedler and Weiss suggest that dimerization is mediated entirely through the phosphorylated receiver domain (5). Both alternatives presented above are compatible with dimerization of the receiver domain.

The DNA-binding constants reported in this paper differ from those previously reported (12, 18). However, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first direct comparison of PhoB and PhoBDBD for DNA binding and transcriptional activation. Previously it was shown, using gel mobility shift assays, that native PhoB binds to the consensus pho box with a KD of approximately 4 μM, which is approximately 10-fold greater than the value reported in this paper (18). Although the gel mobility shift assay is commonly used, it has some drawbacks in quantifying DNA binding. The most important of these is that it is not performed under equilibrium conditions and that some protein-DNA complexes are not stable during electrophoresis (3, 8, 22). It had also previously been shown, using DNase I protection assays, that the DBD from PhoB bound the pho box with a KD of 510 nM (12). A problem with this assay is that the DNA-binding protein must compete with DNase I for target DNA, which may lead to an overestimated value for the KD. In addition, that study employed the pstS promoter which is different from the consensus sequence used in the present study in that it consists of two tandem copies of a near-consensus pho box (12).

The ability of the DBD to activate transcription of phoA has previously been shown in vivo by detecting the induction of phoA on selective plates (12). However, in the present study we have directly compared PhoB to PhoBDBD in their ability to activate transcription. Our results clearly demonstrate that the liberated DBD of PhoB is a much better transcriptional activator than unphosphorylated PhoB.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by Public Health Service grant GM53981 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences.

We thank Mindy Allen and Kym Zumbrennen for helpful discussions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ames S K, Frankema N, Kenney L J. C-terminal DNA binding stimulates N-terminal phosphorylation of the outer membrane protein regulator OmpR from Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:11792–11797. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.21.11792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baikalov I, Schroder I, Kaczor-Grzeskowiak M, Grzeskowiak K, Gunsalus R P, Dickerson R E. Structure of the Escherichia coli response regulator NarL. Biochemistry. 1996;35:11053–11061. doi: 10.1021/bi960919o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benson F E, West S C. Substrate specificity of the Escherichia coli RuvC protein. Resolution of three- and four-stranded recombination intermediates. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:5195–5201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dutta R, Qin L, Inouye M. Histidine kinases: diversity of domain organization. Mol Microbiol. 1999;34:633–640. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01646.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fiedler U, Weiss V. A common switch in activation of the response regulators NtrC and PhoB: phosphorylation induces dimerization of the receiver modules. EMBO J. 1995;14:3696–3705. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00039.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haldimann A, Daniels L L, Wanner B L. Use of new methods for construction of tightly regulated arabinose and rhamnose promoter fusions in studies of the Escherichia coli phosphate regulon. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:1277–1286. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.5.1277-1286.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Head C G, Tardy A, Kenney L J. Relative binding affinities of OmpR and OmpR-phosphate at the ompF and ompC regulatory sites. J Mol Biol. 1998;281:857–870. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hill J J, Royer C A. Fluorescence approaches to study of protein-nucleic acid complexation. Methods Enzymol. 1997;278:390–416. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(97)78021-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoch J A, Silhavy T J. Two-component signal transduction. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kumar A, Grimes B, Fujita N, Makino K, Malloch R A, Hayward R S, Ishihama A. Role of the sigma70 subunit of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase in transcription activation. J Mol Biol. 1994;235:405–413. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lupas A, Stock J. Phosphorylation of an N-terminal regulatory domain activates the CheB methylesterase in bacterial chemotaxis. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:17337–17342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Makino K, Amemura M, Kawamoto T, Kimura S, Shinagawa H, Nakata A, Suzuki M. DNA binding of PhoB and its interaction with RNA polymerase. J Mol Biol. 1996;259:15–26. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Makino K, Amemura M, Kim S-K, Nakata A, Shinagawa H. Mechanism of transcriptional activation of the phosphate regulon in Escherichia coli. In: Torriani-Gorini A, Yagil E, Silver S, editors. Phosphate in microorganisms: cellular and molecular biology. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1994. pp. 5–12. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Makino K, Shinagawa H, Amemura M, Kawamoto T, Yamada M, Nakata A. Signal transduction in the phosphate regulon of Escherichia coli involves phosphotransfer between PhoR and PhoB proteins. J Mol Biol. 1989;210:551–559. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(89)90131-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Makino K, Shinagawa H, Amemura M, Nakata A. Nucleotide sequence of the phoR gene, a regulatory gene for the phosphate regulon of Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol. 1986;192:549–556. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(86)90275-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Makino K, Shinagawa H, Nakata A. Regulation of the phosphate regulon of Escherichia coli K-12: regulation and role of the regulatory gene phoR. J Mol Biol. 1985;184:231–240. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(85)90376-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martinez-Hackert E, Stock A M. Structural relationships in the OmpR family of winged-helix transcription factors. J Mol Biol. 1997;269:301–312. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCleary W R. The activation of PhoB by acetylphosphate. Mol Microbiol. 1996;20:1155–1163. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02636.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Neidhardt F C, Umbarger H E. Chemical composition of Escherichia coli. In: Neidhardt F C, Curtiss III R, Ingraham J L, Lin E C C, Low K B, Magasanik B, Reznikoff W S, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1996. pp. 13–16. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Okamura H, Hanaoka S, Nagadoi A, Makino K, Nishimura Y. Structural comparison of the PhoB and OmpR DNA-binding/transactivation domains and the arrangement of PhoB molecules on the phosphate box. J Mol Biol. 2000;295:1225–1236. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parkinson J S, Kofoid E C. Communication modules in bacterial signaling proteins. Annu Rev Genet. 1992;26:71–112. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.26.120192.000443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parsons C A, West S C. Formation of a RuvAB-Holliday junction complex in vitro. J Mol Biol. 1993;232:397–405. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sevenich F W, Langowski J, Weiss V, Rippe K. DNA binding and oligomerization of NtrC studied by fluorescence anisotropy and fluorescence correlation spectroscopy. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:1373–1381. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.6.1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shinagawa H, Makino K, Amemura M, Nakata A. Structure and function of the regulatory genes for the phosphate regulon in Escherichia coli. In: Torriani-Gorini A, Rothman F G, Silver S, Wright A, Yagil E, editors. Phosphate metabolism and cellular regulation in microorganisms. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1987. pp. 20–25. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sola M, Gomis-Ruth F X, Serrano L, Gonzalez A, Coll M. Three-dimensional crystal structure of the transcription factor PhoB receiver domain. J Mol Biol. 1999;285:675–687. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stock J B, Ninfa A J, Stock A M. Protein phosphorylation and the regulation of adaptive responses in bacteria. Microbiol Rev. 1989;53:450–490. doi: 10.1128/mr.53.4.450-490.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Torriani-Gorini A. Introduction: the Pho regulon of Escherichia coli. In: Torriani-Gorini A, Yagil E, Silver S, editors. Phosphate in microorganisms: cellular and molecular biology. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1994. pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Volz K. Structural conservation in the CheY superfamily. Biochemistry. 1993;32:11741–11753. doi: 10.1021/bi00095a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wanner B L. Phosphate signaling and the control of gene expression in Escherichia coli. In: Silver S, Walden W, editors. Metal ions in gene regulation. Sterling, Va: Chapman and Hall, Ltd.; 1997. pp. 104–128. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wanner B L. Phosphorous assimilation and control of the phosphate regulon. In: Neidhardt F C, Curtiss III R, Ingraham J L, Lin E C C, Low K B, Magasanik B, Reznikoff W S, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1996. pp. 1357–1381. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weiss D S, Klose K E, Hoover T R, North A, Porter S, Wedel A B, Kustu S. Prokaryotic transcriptional enhancers. In: McKnight S L, Yamamoto K R, editors. Transcriptional regulation. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1992. pp. 667–694. [Google Scholar]