Abstract

One of the earliest events in the Myxococcus xanthus developmental cycle is production of an extracellular cell density signal called A-signal (or A-factor). Previously, we showed that cells carrying an insertion in the asgE gene fail to produce normal levels of this cell-cell signal. In this study we found that expression of asgE is growth phase regulated and developmentally regulated. Several lines of evidence indicate that asgE is cotranscribed with an upstream gene during development. Using primer extension analyses, we identified two 5′ ends for this developmental transcript. The DNA sequence upstream of one 5′ end has similarity to the promoter regions of several genes that are A-signal dependent, whereas sequences located upstream of the second 5′ end show similarity to promoter elements identified for genes that are C-signal dependent. Consistent with this result is our finding that mutants failing to produce A-signal or C-signal are defective for developmental expression of asgE. In contrast to developing cells, the large majority of the asgE transcript found in vegetative cells appears to be monocistronic. This finding suggests that asgE uses different promoters for expression during vegetative growth and development. Growth phase regulation of asgE is abolished in a relA mutant, indicating that this vegetative promoter is induced by starvation. The data presented here, in combination with our previous results, indicate that the level of AsgE in vegetative cells is sufficient for this protein to carry out its function during development.

When Myxococcus xanthus is deprived of nutrients, approximately 100,000 rod-shaped cells initiate a complex social interaction that culminates in construction of a multicellular structure called a fruiting body (5, 15, 32). After cells aggregate into fruiting bodies, individual rod-shaped cells within these structures begin to differentiate into spherical spores that are resistant to certain types of environmental stress. Thus, the M. xanthus developmental cycle occurs in an ordered series of steps that include starvation, construction of a macroscopic fruiting body, and differentiation of rod-shaped cells into spherical spores.

Constructing multicellular structures requires cells to coordinate their activities. Previous analyses of conditional developmental mutants suggest that M. xanthus coordinates fruiting body development by producing cell-cell signals (4, 10, 25). Kuspa et al. (22) and Kroos and Kaiser (19) showed that two developmental signals, A-signal and C-signal, are required for expression of particular groups of developmentally regulated lacZ reporter gene fusions, indicating that these cell-cell signals may guide the developmental process by directing changes in gene expression. The fact that full expression of nearly all developmentally regulated lacZ reporter gene fusions requires an intact A-signaling system, whereas an intact C-signaling system is required only for expression of lacZ fusions activated after 6 h of development, suggests that A-signal is required earlier in development than C-signal.

Extracellular A-signal consists of a mixture of amino acids and peptides, which are heat stable, and at least two extracellular proteases, which are heat labile (23, 27). Based on these findings, it was proposed that A-signal is a mixture of amino acids and peptides generated by proteolysis (23, 27). Work done by Kuspa et al. (24) suggests that the concentration of A-signal produced by developing cells may serve as an indicator of cell density; A-signal is produced in proportion to the number of cells. A-signal may, therefore, allow M. xanthus cells to determine whether a sufficient number of cells is present to initiate fruiting body development.

Genetic analysis of the original collection of A-signal-defective mutants led to the discovery of three genes (asgA, asgB, and asgC) involved in the production of A-signal (21, 25, 29). Further studies demonstrated that the level of A-signal produced by these asg mutants is between 5.0 and 20.0% of that produced by wild-type cells, resulting in defects in aggregation, sporulation, and expression of developmentally regulated genes (3, 20, 21, 27, 29). Based on DNA sequence analysis of asgA, asgB, and asgC, it was proposed that the products of these genes are components of a signal transduction pathway regulating expression of genes directly involved in production of A-signal (3, 28, 29).

Recent studies of M. xanthus developmental mutants have led to the discovery of two new asg alleles, asgD and asgE (2, 9). Mutants carrying an asgD mutation appear to be unable to recognize starvation properly; these mutants fail to develop unless rapid starvation is induced. Cells carrying an insertion in the asgE gene generate a reduced level of A-signal. The level of A-signal produced by asgE cells, however, is higher than that produced by asgA or asgB cells. Thus, the developmental defects of an asgE mutant are less severe than those of an asgA or asgB mutant. Further analysis of asgE cells showed that they are almost completely lacking heat-labile A-signal activity.

Since we are interested in understanding how the genes required for production of A-signal are regulated, we examined developmental expression of the asgE gene in wild-type cells and in mutants that lack critical components of the M. xanthus developmental cycle. To further understand the mechanism of asgE regulation during development, the structure of the asgE operon was analyzed and putative transcriptional start sites were identified. Because we found that asgE is growth phase regulated, we examined the mechanism of asgE expression in vegetative cells and compared our results to those observed for cells placed under developmental conditions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

A complete list of strains and plasmids used in this study is given in Table 1. Construction of the asgE::lacZ fusion, Ω5003, was described previously (9). The orf2::lacZ fusion, Ω5005, was created by integrating pBMG4 (Table 1) into the orf2 chromosomal locus as described below. Homologous recombinants were distinguished from site-specific recombinants by Southern blot analysis (30).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristics | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli strain | ||

| DH5α | supE44 ΔlacU169 φ80ΔlacZM15 hsdR17 recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 relA1 | 26 |

| M. xanthus strains | ||

| DK101 | pilQ1 (wild-type development) | 13 |

| DK476 | pilQ1 asgA476 | 10 |

| DK480 | pliQ1 asgB480 | 10 |

| DK527 | pilQ1 relA | 12 |

| DK767 | pilQ1 asgC767 | 10 |

| DK5216 | pilQ1 csgA::Tn5132 (ΩLS205) | 33 |

| MS2020 | pilQ1 orf2::pBMG3 (Ω5002) | 9 |

| MS2021 | pilQ1 asgE::pREG-JP2B (Ω5003) | 9 |

| MS2036 | pilQ1 relA asgE::pREG-JP2B (Ω5003) | This study |

| MS2037 | pilQ1 asgB480 asgE::pREG-JP2B (Ω5003) | This study |

| MS2038 | pilQ1 asgA476 asgE::pREG-JP2B (Ω5003) | This study |

| MS2039 | pilQ1 asgC767 asgE::pREG-JP2B (Ω5003) | This study |

| MS2040 | pilQ1 orf2::pBMG4 (Ω5005) | This study |

| MS2041 | pilQ1 csgA::Tn5132 (ΩLS205) | This study |

| asgE::pREG-JP2B (Ω5003) | ||

| Plasmids | ||

| pBGS18 | Kanr | 34 |

| pBluescript II SK | Ampr | Stratagene |

| pREG1727 | Ampr Kanr | 6 |

| pBMG3 | Kanr, pBGS18 containing 0.5 kb of orf2 on a XbaI-BamHI fragment | 9 |

| pBMG4 | Ampr Kanr, pREG1727 containing 1.0 kb of orf2 and 1.5 kb of upstream DNA on an XhoI-BamHI fragment | This study |

| pELF3 | Kanr, pBGS18 containing orf2, asgE, and 0.4 kb of downstream DNA on a BamHI-PstI fragment | 9 |

| pREG-JP2B | Ampr Kanr, pREG1727 containing 1.0 kb of asgE on a BamHI-HindIII fragment | 9 |

Plasmid transfer to M. xanthus.

Plasmids containing DNA fragments from the asgE locus were electroporated into M. xanthus cells using the technique of Plamann et al. (28). Following electroporation, cells were placed into flasks containing 1.5 ml of CTT (see below) broth and incubated at 32°C for 8 h with vigorous agitation. Aliquots (500 μl) of these cultures were added to 5 ml of CTT soft agar and poured onto CTT plates containing kanamycin. Chromosomal DNA was isolated from Kanr colonies (30) and used for Southern blot analysis (30) to identify transformants that contain a single copy of the appropriate plasmid integrated by homologous recombination into the asgE locus. Kanr transformants carrying a single plasmid insertion were used in expression studies as described below.

Media for growth and development.

M. xanthus strains were grown at 32°C in CTT broth containing 1% Casitone (Difco Laboratories), 10.0 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 1 mM KH2PO4, and 8 mM MgSO4 or on plates containing CTT broth and 1.5% Difco Bacto-Agar. CTT broth and CTT plates were supplemented with 40 μg of kanamycin sulfate (Sigma)/ml or 12.5 μg of oxytetracycline (Sigma)/ml as needed. CTT soft agar is CTT broth containing 0.7% Difco Bacto-Agar. Escherichia coli strain DH5α was grown at 37°C in Luria broth (LB) containing 1% tryptone (Difco), 0.5% yeast extract (Difco), and 0.5% NaCl or on plates containing LB and 1.5% Difco Bacto-Agar. LB and LB plates were supplemented with 50 μg of ampicillin (Sigma)/ml or 40 μg of kanamycin sulfate (Sigma)/ml as needed. Fruiting body development was carried out at 32°C on plates containing TPM buffer (10.0 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 1 mM KH2PO4, and 8 mM MgSO4) and 1.5% Difco Bacto-Agar.

Expression studies.

The promoterless lacZ expression vector pREG1727 carries the Mx8 attP site, allowing for site-specific integration at the chromosomal Mx8 phage attachment site attB (6). When we cloned fragments of the asgE locus into pREG1727 and electroporated these plasmids into DK101 cells, we found that a substantial portion of the Kanr colonies (5.0 to 50.0%, depending on the fragment) contained a plasmid integration at the chromosomal asgE locus, rather than an integration at the Mx8 attB. Hence, many of the pREG1727 derivatives were integrating into the chromosomal asgE locus by homologous recombination. Taking advantage of this frequency of homologous recombination, we were able to create a series of lacZ reporter fusions in the vicinity of the asgE locus for expression studies.

For these studies, vegetatively growing cells and developmental cells were harvested and quick frozen in liquid nitrogen as described previously (8). β-Galactosidase assays were performed on quick-frozen cell extracts using the technique of Kaplan et al. (16). β-Galactosidase-specific activity is defined as nanomoles of o-nitrophenol (ONP) produced minute−1 milligram of protein−1.

RNA was isolated from quick-frozen cell extracts by the hot phenol method (30). Total cellular RNA was used for slot blot hybridization analysis as described previously (8, 16). The probe used for these experiments is a 1.0-kb SacI-PvuII fragment from the 5′ end of the asgE gene. Total RNA was isolated from cells after 12 h of development on TPM starvation agar or from cells grown to a density of 109 cells per ml in CTT nutrient broth.

Primer extension analyses.

Primer extension analyses were carried out as described by Garza et al. (8) using RNA isolated from vegetatively growing cells (109 cells per ml) or from cells after 12 h of development on TPM agar. The primers used for this analysis, ade-9 and asgE-veg1, are complementary to sequences in the 5′ end of orf2 and asgE, respectively. DNA was sequenced by the dideoxynucleotide chain termination method (31) using a Sequi-Therm Cycle Sequencing Kit (Epicentre Technologies, Madison, Wis.) and custom-designed oligonucleotide primers. Primers were synthesized by Operon Technologies, Inc. (Alameda, Calif.).

RESULTS

Expression of asgE during growth and development.

To determine whether asgE is developmentally regulated, we cloned a 1.0-kb internal fragment of this gene into the promoterless lacZ expression vector pREG1727 (6). When this plasmid (pREG-JP2B) is integrated into the chromosome of wild-type DK101 cells by homologous recombination, a transcriptional fusion between lacZ and the asgE gene is created. The location of this reporter gene fusion (Ω5003) is shown on the physical map of the asgE locus (Fig. 1), and the pattern of asgE::lacZ expression in cells developing on TPM agar is shown in Fig. 2A. β-Galactosidase-specific activity in cells carrying the asgE::lacZ fusion began to increase relatively early in the developmental process (2 to 4 h) and continued to increase until about 24 h of development on TPM agar. Between 0 and 24 h, the levels of β-galactosidase in cells carrying asgE::lacZ increased approximately threefold, indicating that asgE is developmentally regulated.

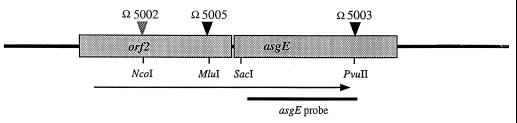

FIG. 1.

Physical map of the asgE locus. Boxes show the locations of the indicated open reading frames, and the arrows show their predicted direction of transcription. Black triangles mark the locations of lacZ reporter gene fusions Ω5003 and Ω5005; the gray triangle shows the location of the orf2 insertion in strain MS2020. The broadened black line represents the 1-kb fragment of the asgE gene that was used as a probe for RNA slot blot analysis.

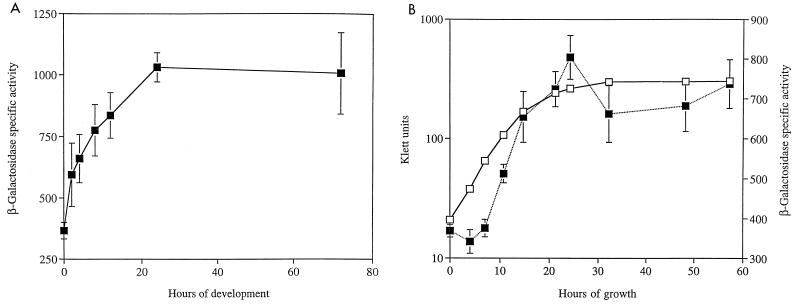

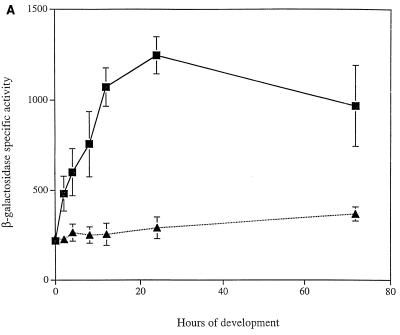

FIG. 2.

Patterns of asgE expression during growth and development. Expression was monitored using the asgE::lacZ reporter gene fusion Ω5003 in strain MS2021. Mean β-galactosidase-specific activities (defined as nanomoles of ONP produced minute−1 milligram of protein−1) were determined from three independent experiments. Error bars represent the standard deviations of the mean. Black squares represent β-galactosidase-specific activity, while empty squares represent cell density. Expression of asgE during development on TPM starvation agar (A) and growth in CTT nutrient broth (B) is shown.

Cells carrying the asgE::lacZ fusion produce approximately 300 to 350 U of β-galactosidase-specific activity prior to the onset of development, which suggests that asgE is expressed during vegetative growth. To investigate this further, we monitored β-galactosidase levels in cells carrying the asgE::lacZ reporter while they were growing in CTT nutrient broth. The data in Fig. 2B indicate that expression of asgE is induced around mid- to late exponential growth phase in nutrient broth and that expression continues to increase until cells begin to enter stationary phase. Between exponential growth and stationary phases, asgE expression increases approximately 2.5-fold. Taken with our previous findings, these results indicate that asgE is both growth phase regulated and developmentally regulated.

Organization of the asgE operon.

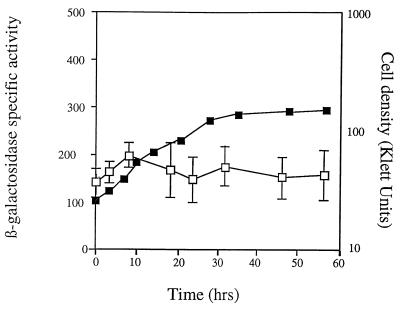

Previously, Garza et al. (9) demonstrated that asgE is located immediately downstream of an open reading frame designated orf2 (Fig. 1). The results of genetic studies and DNA sequence analysis suggest that asgE and orf2 may be cotranscribed during development. To examine whether asgE and orf2 are part of the same operon, we generated the Ω5005 transcriptional fusion between orf2 and lacZ. Subsequently, we monitored the levels of β-galactosidase produced by cells carrying the orf2 reporter fusion at various times during development on TPM starvation agar (Fig. 3A). Consistent with the idea that orf2 and asgE are under the transcriptional control of the same developmental promoter, the pattern of β-galactosidase production from cells carrying the orf2::lacZ fusion was virtually identical to the pattern observed for cells carrying the asgE::lacZ fusion. Furthermore, the mean fold increase in β-galactosidase-specific activity during development was similar for both strains: 2.7 ± 0.1-fold for orf2::lacZ cells and 2.8 ± 0.2-fold for asgE::lacZ cells.

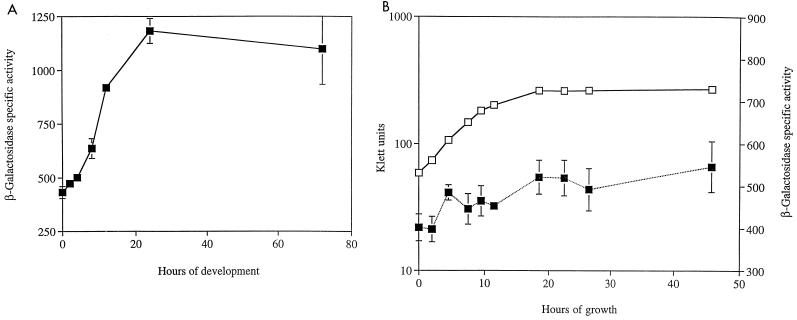

FIG. 3.

Patterns of orf2 expression during growth and development. Expression was monitored using the orf2::lacZ reporter gene fusion Ω5005 in strain MS2040. Mean β-galactosidase-specific activities (defined as nanomoles of ONP produced minute−1 milligram of protein−1) were determined from three independent experiments. Error bars represent the standard deviations of the mean. Black squares represent β-galactosidase-specific activity, while empty squares represent cell density. Expression of orf2 during development on TPM starvation agar (A) and growth in CTT nutrient broth (B) is shown.

To confirm that asgE and orf2 are cotranscribed during development, we used RNA slot blots to show that an insertion in orf2 has a polar effect on transcription of the downstream asgE gene. For these experiments, 12-h developmental RNA was isolated from wild-type DK101 cells and from isogenic cells carrying the Ω5002 insertion in orf2 (MS2020). RNA slot blots were probed with a 1.0-kb fragment of the asgE gene, and the relative levels of asgE mRNA were quantified. The results shown in Fig. 4 demonstrate that the level of asgE mRNA in MS2020 cells after 12 h of development is approximately 8.0% of that in wild-type cells, supporting the idea that asgE and orf2 are under the control of the same developmental promoter.

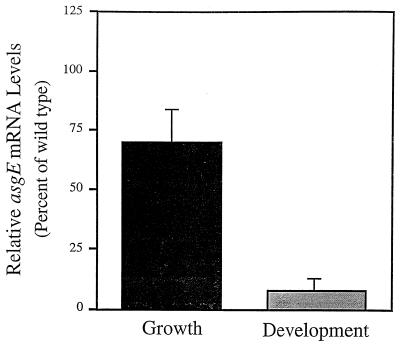

FIG. 4.

Levels of asgE mRNA in an orf2 insertion mutant. Slot blot hybridization experiments were performed with RNA isolated from wild-type strain DK101 and from isogenic strain MS2020, which carries the Ω5002 insertion in orf2. RNA was isolated from cells after 12 h of development on TPM agar and from cells that were grown to a density of 109 cells per ml in nutrient broth. The probe for these experiments was a 1-kb SacI-PvuII fragment of the asgE gene. For each experiment, the level of asgE mRNA in the MS2020 mutant was normalized to the level in wild-type DK101 cells. The mean values shown were derived from three independent experiments. Error bars represent the standard deviations of the mean.

To examine whether asgE and orf2 are cotranscribed in vegetative cells, we monitored expression of the orf2::lacZ reporter gene fusion in MS2040 cells while they were growing in CTT nutrient broth (Fig. 3B). In contrast to the 2.5-fold induction observed for the asgE::lacZ fusion, the levels of β-galactosidase in cells carrying a lacZ reporter gene fusion to orf2 remain relatively unchanged during growth phase, suggesting that orf2 and asgE may be under the control of different vegetative promoters. To confirm this proposal, we used RNA slot blots to show that an insertion in orf2 fails to abolish the transcription of asgE via a polar effect. For these experiments, we used a 1-kb fragment of the asgE gene as the probe and RNA isolated from cells grown in CTT broth. The data presented in Fig. 4 show that the level of asgE mRNA is approximately 70.0% of the wild-type level in the orf2 insertion mutant. Taken with the lacZ expression studies, these data indicate that asgE has its own promoter for driving transcription during vegetative growth. However, asgE mRNA levels are reduced by 30.0% in the orf2 insertion mutant, indicating that at least some asgE expression during vegetative growth is coming from a promoter located upstream of orf2.

Developmental expression of asgE in signaling mutants.

As described above, asgE and orf2 appear to be cotranscribed during development, and expression is induced at about 2 to 4 h poststarvation, indicating that the asgE operon (orf2 and asgE) is induced relatively early in the M. xanthus developmental process. To further our understanding of how the asgE operon is regulated during development, we introduced the promoterless asgE::lacZ fusion plasmid into the chromosome of different developmental mutants and monitored the patterns of expression on TPM starvation agar.

Expression of the asgE::lacZ fusion was first examined in a strain carrying a mutation in the relA gene. An intact copy of relA is required for synthesis of the intracellular starvation signal (p)ppGpp, and accumulation of this signaling molecule is required for the earliest events in development, including production of A-signal (12). Consistent with the finding that asgE is part of the A-signal-generating pathway (9), we found that developmental expression of asgE::lacZ is abolished in cells carrying the relA mutation (Fig. 5A).

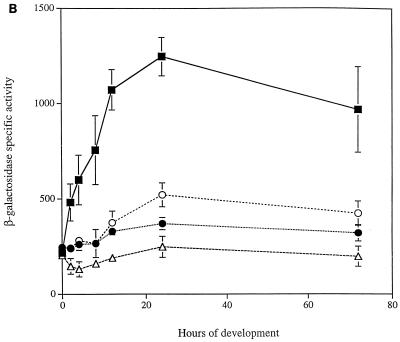

FIG. 5.

Developmental expression of asgE in signaling mutants. The asgE::lacZ reporter gene fusion Ω5003 was introduced into mutants as described in Materials and Methods, and β-galactosidase-specific activity (defined as nanomoles of ONP produced minute−1 milligram of protein−1) was monitored at various times during development on TPM agar. Mean β-galactosidase-specific activities were determined from three independent experiments. Error bars represent the standard deviations of the mean. β-Galactosidase-specific activities for strain MS2021 (black squares) are compared to those of relA strain MS2036 (black triangles) (A); asgA strain MS2036 (black circles), asgB strain MS2037 (empty circles), and asgC strain MS2039 (empty triangles) (B); and csgA strain MS2041 (empty diamonds) (C).

Previous work suggests that the products of asgA, asgB, and asgC genes may serve as regulatory factors that modulate the expression of genes required for A-signal production (3, 28, 29). Because asgE is required for production of heat-labile A-signal, we wanted to determine whether the developmental expression of asgE requires functional copies of these three asg genes. Accordingly, we introduced the asgE::lacZ fusion into strains carrying a mutation in asgA, asgB, or asgC. As shown in Fig. 5B, the level of β-galactosidase produced by cells carrying an asgA, asgB, or asgC mutation is lower than in cells carrying the wild-type counterpart. The effect, however, that each asg mutation has on the expression of asgE::lacZ appears to be somewhat different; peak expression (24 h poststarvation) of asgE::lacZ is about 40.0% of the wild-type level in asgB cells, 30.0% in asgA cells, and 20.0% in asgC cells. These findings indicate that full expression of asgE during development is dependent on the asgA, asgB, and asgC gene products.

It has been shown that csgA mutants, which are defective for production of C-signal, fail to fully express genes that are induced after 6 h of development (19). Since developmental expression of asgE begins around this time, we wanted to know whether developmental expression of the asgE operon requires C-signaling. Therefore, we introduced the asgE::lacZ fusion plasmid into a strain that carries a csgA mutation and assayed for β-galactosidase expression during development on TPM starvation agar. The results shown in Fig. 5C indicate that developmental induction of the asgE::lacZ fusion is abolished in the csgA mutant.

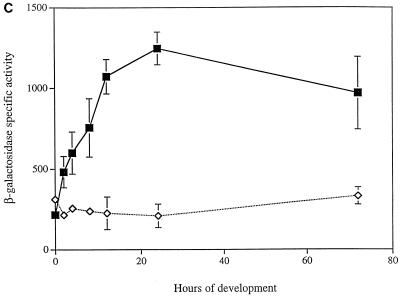

Vegetative expression of asgE in a relA mutant.

The pattern of growth phase regulation that we observed for asgE is strikingly similar to that of sdeK, a (p)ppGpp-dependent gene required for development in M. xanthus (8, 12). Because of this similarity, we wanted to know whether the growth phase regulation of asgE is (p)ppGpp dependent. Hence, we examined expression of the asgE::lacZ reporter fusion in a relA mutant during growth in CTT nutrient broth (Fig. 6). Consistent with the proposal that vegetative induction of asgE is (p)ppGpp dependent, we found that growth phase regulation of asgE is abolished in the relA mutant; no increase in β-galactosidase-specific activity is observed when cells enter mid- to late exponential growth phase in CTT. In contrast, the asgA, asgB, asgC, and csgA mutations, which block developmental expression of asgE, have no observable effect on the growth phase regulation of asgE (data not shown).

FIG. 6.

Effect of a relA mutation on vegetative expression of asgE. Expression was monitored using the asgE::lacZ reporter gene fusion Ω5003 in strain MS2036. Mean β-galactosidase-specific activities were determined from three independent experiments. Error bars represent the standard deviations of the mean. Empty squares represent β-galactosidase-specific activity (defined as nanomoles of ONP produced minute−1 milligram of protein−1), while black squares represent cell density.

Mapping the 5′ ends of asgE transcripts.

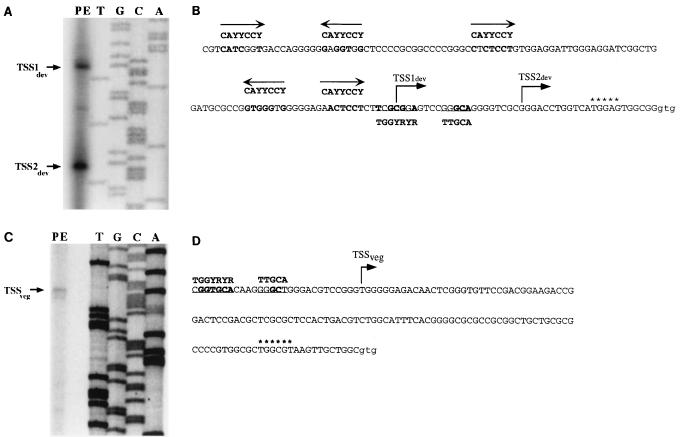

To identify the 5′ end(s) of the asgE developmental transcript, primer extension analysis was performed with 12-h developmental RNA and a primer that is complementary to the region immediately downstream of the 5′ end of the orf2 gene. The results given in Fig. 7A show that two bands corresponding to two 5′ ends (TSS1dev and TSS2dev) were identified using primer extension. One of the 5′ ends maps to a guanine nucleotide 23 bp upstream of the putative start for the Orf2 protein coding sequence. The second 5′ end maps to a cytosine nucleotide 44 bp upstream of the Orf2 start codon. No bands were identified by primer extension when we used developmental RNA and primers complementary to the 5′ end of the asgE gene (data not shown), further supporting the idea that developmental expression of asgE is driven solely by a promoter(s) located upstream of orf2.

FIG. 7.

(A) Mapping the 5′ ends of the asgE developmental transcript by primer extension analysis. A, C, T, and G show the DNA sequencing ladders. PE, primer extension using total RNA prepared from DK101 cells developing on TPM agar for 12 h and primer ade9 (Materials and Methods). (B) DNA sequence of the region upstream of orf2. The putative GTG start codon for the ORF2 coding sequence is shown in lowercase letters, and nucleotides that form a potential ribosome binding site are marked with asterisks. The bent arrows above the guanine nucleotide at position −23 and the cytosine nucleotide at position −44 represent the two 5′ ends identified by primer extension. Regions of similarity to the consensus sequence for the ς54 family of promoters (35) (depicted below the sequence) and to the C box consensus sequence (7) (5′-CAYYCCY-3′, depicted above the sequence) are in boldface. Arrows above the C box sequences indicate the directionality of the C box with respect to the DNA strand shown. (C) Mapping of the 5′ end of the asgE vegetative transcript by primer extension analysis. A, C, T, and G show the DNA sequencing ladders. PE, primer extension using total RNA from DK101 cells grown in CTT to a density of 109 cells per ml and primer asgE-veg1. (D) DNA sequence of the region upstream of asgE. Symbols and descriptions are the same as for panel B, except that the ς54 consensus sequence is shown above the DNA sequence.

When we examined the region preceding TSS2dev, we found sequences with similarity to the ς54 family of promoters (35) and Fig. 7B). This family of promoters has two conserved regions centered 12 and 24 bp upstream of the transcriptional start site. We found the strongest overall similarity in the −24 region, with five of seven nucleotides identical to the ς54 consensus sequence. The −24 region for TSS2dev has a CG dinucleotide instead of the highly conserved GG dinucleotide. Keseler and Kaiser (17) found a similar result when they analyzed the ς54-type promoter that directs transcription of the 4521 gene during development. In the −12 region of TSS2dev, three of five matches to the ς54 consensus were found, including the highly conserved GC dinucleotide.

Two sets of sequences positioned around −14 and −65 bp upstream of TSS1dev show similarity to the CAYYCCY heptanucleotide (C box) found in the promoter regions of several C-signal-dependent genes (1, 6, 7) (Fig. 7B). At both the −14 and −65 positions, six of seven nucleotides matched those found in the C box. When we examined the DNA strand opposite the one shown in Fig. 7B, we found two additional regions centered around −23 bp (six of seven matches) and −89 bp (five of seven matches) upstream of TSS1dev that show similarity to the C box sequences.

To identify the 5′ end(s) of the asgE vegetative transcript, primer extension analysis was performed with RNA isolated from vegetative cells and a primer that is complementary to the region immediately downstream of the 5′ end of the asgE gene. The results given in Fig. 7C show that one band corresponding to one 5′ end (TSSveg) was identified 128 bp upstream of asgE by using primer extension. As shown in Fig. 7D, sequences upstream of TSSveg show similarity to the ς54 family of promoters (35). The strongest overall similarity is in the −24 region, with six of seven nucleotides identical to the ς54 consensus sequence, including the highly conserved GG dinucleotide. The similarity is less conserved around the −12 region, with only two of five matches to the consensus. However, the highly conserved GC dinucleotide is present.

DISCUSSION

When confronted with nutrient limitation, M. xanthus cells must decide whether or not to initiate development and begin to build a multicellular fruiting body. Because A-signal is produced in proportion to cell numbers (24), nutrient-deprived cells can sample the concentration of this extracellular signal and determine whether the population is sufficient to complete development. Consequently, A-signal helps M. xanthus make this critical decision at the onset of starvation, and mutants that fail to produce normal levels of this signal are defective for most of the important events associated with development.

Many of the steps that lead to A-signal production are unclear, although two forms of A-signal have been identified. One form of A-signal consists of a mixture of amino acids and peptides, which are heat stable, and the other form contains at least two extracellular proteases, which are heat labile (23, 27). It has been previously demonstrated that disruption of the asgE gene causes cells to be almost completely devoid of the extracellular protease activity associated with heat-labile A-signal (9). Hence, asgE mutants are defective for a variety of A-signal-dependent events, including aggregation, sporulation, and developmental gene expression.

In the work presented here, we examined the regulation of asgE to help uncover the events that lead to production of heat-labile A-signal. We found that the regulation of asgE is complex; expression of asgE is both growth phase regulated and developmentally regulated. During development, expression of asgE begins to increase relatively early (2 to 4 h), around the time that cells are beginning to aggregate into mounds. Peak expression of asgE occurs at about 24 h of development, and input from the A-signaling and C-signaling systems is required for this peak level of induction. During vegetative growth, expression is induced when cells reach mid- to late exponential phase, and expression continues to increase until cells begin to enter stationary phase.

In a previous study, the DNA sequence of the asgE locus led researchers to speculate that asgE may be part of a two-gene operon, which includes the upstream gene orf2 (9). In this study, we have examined the structure of the asgE operon during growth and development. During growth, the dominant promoter (Pveg) controlling asgE expression appears to be located immediately upstream of the asgE gene itself, rather than upstream of orf2. We base this conclusion on several lines of evidence. First, asgE appears to be growth phase regulated, while orf2 is not. Second, an insertion in orf2 reduces transcription of asgE mRNA by only 30.0%. Third, using RNA from growing cells, we identified a putative transcriptional start site about 130 bp upstream of the asgE gene, within the protein coding sequence for Orf2. Like the sdeK promoter, which is a starvation-induced promoter that we examined previously (8), the Pveg promoter is dependent on production of the intracellular starvation signal (p)ppGpp; expression of asgE during growth is reduced by fourfold in a relA mutant. Moreover, the results of primer extension analyses suggest that starvation induction of both sdeK and asgE may be driven by a ς54-like promoter element.

Developmental expression of asgE is also dependent on the (p)ppGpp starvation signal. It appears, however, that control of asgE expression is being shifted to a promoter(s) located upstream of orf2. Hence, we propose that asgE and orf2 are coexpressed from the same developmental promoter(s) (Pdev). This proposal is based on three pieces of data. First, an insertion in orf2 abolishes transcription of asgE developmental mRNA. Second, the patterns of asgE and orf2 expression during development are virtually identical. Finally, primer extension experiments with developmental RNA yielded two potential transcriptional start sites located upstream of orf2, while no transcriptional start sites were identified immediately upstream of asgE (data not shown).

The DNA sequences upstream of this first transcriptional start site have similarity to the ς54 family of promoters, including the ς54-like promoters that drive developmental expression of several A-signal-dependent genes (17, 35). Upstream of the second start site, we found similarity to sequences located upstream of the C-signal-dependent genes Ω4400, Ω4403, and Ω4499 (1, 6, 7). These DNA sequence similarities are consistent with the finding that full induction of asgE during development requires wild-type copies of asgABC, as well as csgA.

Although asgE expression increases during development, we believe that the levels of AsgE in vegetative cells are sufficient for this protein to carry out its function during development. We base this conclusion on the observation that csgA cells, which express asgE during vegetative growth but fail to induce asgE expression during development, can fully rescue the developmental defect of an asgE mutant when the two strains are codeveloped (9). Therefore, csgA cells appear to be able to provide the asgE mutant with sufficient levels of A-signal to rescue its developmental defects. The finding that asgE expression during growth is relatively high compared with that of other developmentally regulated genes is also consistent with the idea that sufficient AsgE is present before development begins (18, 19, 20, 22). Thus, the threefold increase in expression of asgE during development may serve to specifically adjust the levels of the AsgE protein that are already present during growth.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank members of the Singer lab for helpful discussions and for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported (in part) by a National Institutes of Health postdoctoral fellowship (GM19080) to A.G.G. and by a National Institutes of Health grant (GM54592) to M.S.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brandner J P, Kroos L. Identification of the Ω4400 regulatory region, a developmental promoter of Myxococcus xanthus. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:1995–2004. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.8.1995-2004.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cho K, Zusman D R. AsgD, a new two-component regulator required for A-signalling and nutrient sensing during early development of Myxococcus xanthus. Mol Microbiol. 1999;34:268–281. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01594.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davis J M, Mayor J, Plamann L. A missense mutation in rpoD results in an A-signalling defect in Myxococcus xanthus. Mol Microbiol. 1995;18:943–952. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.18050943.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Downard J, Ramaswamy S V, Kil K-S. Identification of esg, a genetic locus involved in cell-cell signaling during Myxococcus xanthus development. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:7762–7770. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.24.7762-7770.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dworkin M. Recent advances in the social and developmental biology of myxobacteria. Microbiol Rev. 1996;60:70–102. doi: 10.1128/mr.60.1.70-102.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fisseha M, Gloudemans M, Gill R E, Kroos L. Characterization of the regulatory region of a cell interaction-dependent gene in Myxococcus xanthus. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:2539–2550. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.9.2539-2550.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fisseha M, Biran D, Kroos L. Identification of the Ω4499 regulatory region controlling developmental expression of a Myxococcus xanthus cytochrome P-450 system. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:5467–5475. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.17.5467-5475.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garza A G, Pollack J S, Harris B Z, Lee A, Keseler I M, Licking E F, Singer M. SdeK is required for early fruiting body development in Myxococcus xanthus. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:4628–4637. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.17.4628-4637.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garza A G, Harris B Z, Pollack J S, Singer M. The asgE locus is required for cell-cell signaling during Myxococcus xanthus development. Mol Microbiol. 2000;35:812–824. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01753.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hagen D C, Bretscher A P, Kaiser D. Synergism between morphogenetic mutants of Myxococcus xanthus. Dev Biol. 1978;64:284–296. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(78)90079-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hanahan D. Studies on transformation of Escherichia coli with plasmids. J Mol Biol. 1983;166:557–580. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(83)80284-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harris B Z, Kaiser D, Singer M. The guanosine nucleotide (p)ppGpp initiates development and A-factor production in Myxococcus xanthus. Genes Dev. 1998;12:1022–1035. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.7.1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hodgkin J, Kaiser D. Cell-to-cell stimulation of movement in nonmotile mutants of Myxococcus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:2938–2942. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.7.2938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaiser D. Social gliding is correlated with the presence of pili in Myxococcus xanthus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:5952–5956. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.11.5952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaiser D, Losick R. How and why bacteria talk to each other. Cell. 1993;73:873–885. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90268-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaplan H B, Kuspa A, Kaiser D. Suppressors that permit A-signal-independent developmental gene expression in Myxococcus xanthus. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:1460–1470. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.4.1460-1470.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Keseler I M, Kaiser D. An early A-signal-dependent gene in Myxococcus xanthus has a ς54-like promoter. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:4638–4644. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.16.4638-4644.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kroos L, Kaiser D. Construction of Tn5lac, a transposon that fuses lacZ expression to exogenous promoters, and its introduction into Myxococcus xanthus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:5816–5820. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.18.5816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kroos L, Kaiser D. Expression of many developmentally regulated genes in Myxococcus depends on a sequence of cell interactions. Genes Dev. 1987;1:840–854. doi: 10.1101/gad.1.8.840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kroos L, Kuspa A, Kaiser D. A global analysis of developmentally regulated genes in Myxococcus xanthus. Dev Biol. 1986;117:252–266. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(86)90368-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuspa A, Kaiser D. Genes required for developmental signalling in Myxococcus xanthus: three asg loci. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:2762–2772. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.5.2762-2772.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kuspa A, Kroos L, Kaiser D. Intercellular signaling is required for developmental gene expression in Myxococcus xanthus. Dev Biol. 1986;117:267–276. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(86)90369-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuspa A, Plamann L, Kaiser D. Identification of heat-stable A-factor from Myxococcus xanthus. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:3319–3326. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.10.3319-3326.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuspa A, Plamann L, Kaiser D. A-signaling and the cell density requirement for Myxococcus xanthus development. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:7360–7369. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.22.7360-7369.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.LaRossa R, Kuner J, Hagen D, Manoil C, Kaiser D. Developmental cell interactions of Myxococcus xanthus: analysis of mutants. J Bacteriol. 1983;153:1394–1404. doi: 10.1128/jb.153.3.1394-1404.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Messing J, Gronenborn B, Muller-Hill B, Hopschneider P. Filamentous coliphage M13 as a cloning vehicle: insertion of a HindII fragment of the lac regulatory region in M13 replicative form in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:3642–3646. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.9.3642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Plamann L, Kuspa A, Kaiser D. Proteins that rescue A-signal-defective mutants of Myxococcus xanthus. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:3311–3318. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.10.3311-3318.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Plamann L, Davis J M, Cantwell B, Mayor J. Evidence that asgB encodes a DNA-binding protein essential for growth and development of Myxococcus xanthus. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:2013–2020. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.7.2013-2020.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Plamann L, Li Y, Cantwell B, Mayor J. The Myxococcus xanthus asgA gene encodes a novel signal transduction protein required for multicellular development. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:2014–2020. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.8.2014-2020.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson A R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shimkets L J. Social and developmental biology of the myxobacteria. Microbiol Rev. 1990;54:473–501. doi: 10.1128/mr.54.4.473-501.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shimkets L J, Asher S J. Use of recombination techniques to examine the structure of the csg locus of Myxococcus xanthus. Mol Gen Genet. 1988;211:63–71. doi: 10.1007/BF00338394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spratt B G, Hedge P J, Heesen S T, Edelman A, Broome-Smith J K. Kanamycin-resistant vectors that are analogs of plasmids pUC8, pUC9, pEMBL8 and pEMBL9. Gene. 1986;41:337–342. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(86)90117-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thöny B, Hennecke H. The −24/−12 promoter comes of age. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1989;63:341–358. doi: 10.1016/0168-6445(89)90028-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]