Abstract

Transcription of the clpP-clpX operon of Escherichia coli leads to the production of two different sizes of transcripts. In log phase, the level of the longer transcript is higher than the level of the shorter transcript. Soon after the onset of carbon starvation, the level of the shorter transcript increases significantly, and the level of the longer transcript decreases. The longer transcript consists of the entire clpP-clpX operon, whereas the shorter transcript contains the entire clpP gene but none of the clpX coding sequence. The RpoH protein is required for the increase in the level of the shorter transcript during carbon starvation. Primer extension experiments suggest that there is increased usage of the ς32-dependent promoter of the clpP-clpX operon within 15 min after the start of carbon starvation. Expression of the clpP-clpX operon from the promoters upstream of the clpP gene decreases to a very low level by 20 min after the onset of carbon starvation. Various pieces of evidence suggest, though they do not conclusively prove, that production of the shorter transcript may involve premature termination of the longer transcript. The half-life of the shorter transcript is much less than that of the longer transcript during carbon starvation. E. coli rpoB mutations that affect transcription termination efficiency alter the ratio of the shorter clpP-clpX transcript to the longer transcript. The E. coli rpoB3595 mutant, with an RNA polymerase that terminates transcription with lower efficiency than the wild type, accumulates a lower percentage of the shorter transcript during carbon starvation than does the isogenic wild-type strain. In contrast, the rpoB8 mutant, with an RNA polymerase that terminates transcription with higher efficiency than the wild type, produces a higher percentage of the shorter clpP-clpX transcript when E. coli is in log phase. These and other data are consistent with the hypothesis that the shorter transcript results from premature transcription termination during production of the longer transcript.

The Clp protease is the second ATP-dependent protease purified from Escherichia coli bacteria (9, 13). Purified Clp protease is composed of an ATP-binding component and a peptide-degrading component (9, 13). The peptide-degrading component of the Clp protease is ClpP (21, 22, 34); the ATP-binding component of the Clp protease may be either the ClpA protein or the ClpX protein (7, 14, 33). The Clp protease can degrade abnormal proteins in vivo (13, 34); it is also responsible for the turnover of specific normal proteins (5, 37). Recognition of specific substrates by the Clp protease is dependent on the particular ATP-binding component of the protease (14, 31). Either ClpA or ClpX can associate with ClpP to form a functional protease, but the ClpAP protease and the ClpXP protease have different substrate specificities (7, 26). The target proteins of the ClpAP protease include a ClpA-LacZ fusion protein and the P1 RepA protein (5, 32); the target proteins of the ClpXP protease include the λ O protein and the E. coli RpoS protein (31, 33).

The clpP and clpX genes form an operon that is located at 23 min on the E. coli genetic map (7, 21). In this operon, clpP is the promoter-proximal gene, and clpX is the promoter-distal gene; there is a 125-bp intercistronic region between clpP and clpX (7, 21). The gene upstream of the clpP-clpX operon encodes the trigger factor, and the gene downstream of the clpP-clpX operon encodes the Lon protease (21). The clpX gene is usually transcribed as part of the clpP-clpX operon (7). A promoter for clpX alone, however, appears to be located in the intercistronic region between clpP and clpX; this promoter may be relatively weak (35).

The promoters immediately upstream of the clpP gene, responsible for transcribing the clpP-clpX operon, include two ς70-dependent promoters (21). The fact that ClpP is an RpoH-dependent heat shock protein (15) suggests that there may also be a heat shock promoter for the clpP gene. By comparing the promoter sequence of the clpP-clpX operon with sequences of known heat shock promoters, a putative heat shock promoter has been identified in the promoter region of the clpP-clpX operon (8). This heat shock promoter is located between the two ς70-dependent promoters (8).

In E. coli, the cellular levels of certain regulatory proteins are actively regulated by proteases (4, 6). The RpoS protein (16, 30), responsible for induction of stationary-phase-specific genes, is degraded by the ClpXP protease (26, 37). During entry into stationary phase, the cellular level of the RpoS protein increases. The increase in RpoS protein appears to be a consequence of increased translation of rpoS mRNA and also of increased stability of RpoS protein (17, 23, 36). When E. coli is ready to leave stationary phase, the ClpXP protease is required to degrade protein products of the stationary-phase-specific genes (3). In this study, we describe some of the effects of carbon deprivation on transcription of the clpP-clpX operon of E. coli.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and strain construction.

The bacterial strains, the transducing phage, and the plasmid used in this study are listed in Table 1. The rpoB mutations in E. coli RFM443 (rpoB8) and in E. coli RFM443 (rpoB3595) were transferred into E. coli E103S/pWPC9 by P1 transduction. P1 transduction was carried out as described by Silhavy et al. (27). Insertion of pWPC9 into bacterial strains was done by electroporation. Electroporation was carried out as described by the manufacturer of the apparatus (Bio-Rad Laboratories).

TABLE 1.

E. coli, bacteriophage, and plasmid

| Strain, phage, or plasmid | Relevant genotype | Source |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli | ||

| E103S | lacI(Ts) metB | Our collection |

| CAG15071 | MC4100 rpoH30::kan suhX401 (λpF13-PrpoDhs-lacZ) | C. Gross |

| CAG15137 | MC4100 suhX401 (λpF13-PrpoDhs-lacZ) | C. Gross |

| E103S rpoB8 | rpoB8 transferred from RFM443 rpoB8 | This study |

| E103S rpoB3595 | rpoB3595 transferred from RFM443 rpoB3595 | This study |

| RFM443 | N99 lac-74 | L. F. Liu |

| RFM443 rpoB8 | N99 lac-74 rpoB8 | L. F. Liu |

| RFM443 rpoB3595 | N99 lac-74 rpoB3595 | L. F. Liu |

| Phage P1 vir | Our collection | |

| Plasmid pWPC9 | S. Gottesman |

Reagents and kits.

Agarose was purchased from Life Technologies. Acidic phenol, amino acids, and ampicillin were purchased from Fisher Scientific. Diethylene pyrocarbonate (DEPC), MgSO4, NaCl, and sodium acetate were purchased from Sigma. The nick translation kit was purchased from Promega. RNA size markers were purchased from Promega.

Carbon starvation of E. coli.

A culture of the E. coli strain to be studied was grown overnight with aeration at 30°C in 1× M9 growth medium (25), which contains 0.2% glucose, required amino acids, and vitamins. After overnight growth, the bacterial culture was diluted into fresh 1× M9 growth medium. The optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of the diluted bacterial culture was adjusted to about 0.02. The culture was then incubated at 30°C with aeration until its OD600 reached 0.2. Half of the bacterial culture was then transferred to a chilled centrifuge tube containing one-half of the original culture volume of ice-cold 40 mM sodium acetate. This bacterial sample, collected in log phase, was kept on ice. The other half of the bacterial culture was collected on a Milli-Q type HA 0.45-μm-pore-size filter membrane. Bacteria on the membrane were washed twice with the same volume of prewarmed 1× M9 wash-starvation medium, which contains required amino acids and vitamins but no glucose. Bacteria on the filter membrane were then resuspended in an equal volume of 1× M9 wash-starvation medium, and the resuspended bacteria were returned to 30°C with aeration. After the desired time of starvation, the culture was transferred to a chilled centrifuge tube containing one-half of the original volume of ice-cold 40 mM sodium acetate. The bacterial samples were then centrifuged in a Sorvall SS34 rotor at 10,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatants were discarded after centrifugation, and the bacterial pellets were stored on dry ice. Then either the bacterial pellets were stored at −70°C, or the RNA was immediately extracted from the frozen bacterial samples.

Extraction of total RNA from E. coli.

The procedure for RNA extraction was a modification of the method described by Aiba et al. (1). Lysis buffer (500 μl) and acidic phenol (500 μl) were added to each bacterial pellet. The bacterial pellets were dissolved in lysis buffer together with acidic phenol by vortexing vigorously. The lysed pellets were then transferred to microcentrifuge tubes, where they were incubated for 5 min at 65°C. The organic solvent was separated from the aqueous solution after centrifugation in a microcentrifuge at maximum speed (14,000 rpm) for 4 min at 4°C. The acidic phenol extraction was repeated two more times. The aqueous solution was extracted again with a 1:1 mixture of acidic phenol and chloroform. The aqueous phase from each sample was then mixed with 3 volumes of absolute ethanol, and the RNA was precipitated on dry ice for 30 min. RNA in the solution was pelleted by centrifugation in a microcentrifuge at maximum speed for 15 min at 4°C. RNA pellets were washed twice with 80% ethanol. Each RNA sample was resuspended in 200 μl of DEPC-treated water, and 10 μl of DEPC-treated 5 M sodium chloride was added to each RNA sample. Three volumes of absolute ethanol was added to each sample. The RNA was again precipitated on dry ice for 30 min. RNA in each sample was recovered after centrifugation in a microcentrifuge at 14,000 rpm for 15 min at 4°C. RNA pellets were washed twice with 80% ethanol. DEPC-treated water was used to resuspend the RNA pellets. The concentration and purity of the RNA samples were determined spectrophotometrically.

Production of the template for the radiolabeled probe used in Northern blotting.

In most experiments, the template used to produce the radiolabeled probe was amplified from pWPC9 by PCR (2). The forward primer, 5′-GTCATACAGCGGCGAACGAG-3′, annealed to the clpP sequence between bp 380 and bp 399. The reverse primer, 5′-CGACCAGACCGTATTCCAC-3′, annealed to the clpP sequence between bp 975 and bp 957. The PCR mix included 10 ng of pWPC9, 1 μg of the forward primer, 1 μg of the reverse primer, 5 μl of 10× buffer for Taq polymerase, 0.5 μl of Taq polymerase, and 41.5 μl of H2O.

The amplification cycles consisted of two stages. The conditions of the first stage were template denaturation for 1 min at 94°C, primer annealing for 30 s at 55°C, and synthesis of new DNA strands for 30 s at 72°C. The first stage included only three cycles. The conditions used in the second stage were template denaturation for 15 s at 94°C, primer annealing for 15 s at 55°C, and synthesis of new DNA strands for 15 s at 72°C. The second stage of amplification included 27 cycles.

Northern blotting.

RNA glyoxal-agarose gel electrophoresis was carried out as described by Ausubel (2). RNA was electrotransferred from the agarose gel to a Zeta probe GT membrane as suggested by the manufacturer of the Zeta probe GT membrane (Bio-Rad Laboratories). The radiolabeled probe used in Northern blotting was produced by nick translation. The probe was labeled during nick translation with [α-32P]dCTP. The template used in nick translation was a PCR fragment amplified from the sequence of the clpP gene between bp 380 and bp 975. Hybridization and prehybridization were carried as recommended by the manufacturer of the Zeta probe GT membrane (Bio-Rad Laboratories).

Primer extension.

The procedure for primer extension was a modification of the method described by Sambrook et al. (25). The primer 5′-TATCTCGTTCGCCGCTGTATGACAT-3′ was used in primer extension. This primer annealed to the noncoding strand of the clpP gene between bp 378 and bp 402. The primer was radiolabeled at its 5′ end by T4 polynucleotide kinase. The primer labeling reaction included 100 ng of the primer in 16 μl of H2O, 1 μl of 20-mCi/ml [γ-32P]ATP, 2 μl of 10× buffer for T4 polynucleotide kinase, and 1 μl of T4 polynucleotide kinase. The reaction mixture was incubated for 1 h at 37°C. T4 polynucleotide kinase was inactivated by incubating the reaction mixture for 15 min at 65°C. The radiolabeled primer was further diluted in 200 μl of DEPC-treated water and then stored at −20°C.

Purified total RNA was mixed with 1.5 μl of 20× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate) (25), 3.6 μl of radiolabeled probe, and 10 μl of H2O. The hybridization reaction was incubated for 90 min at 65°C, after which the hybridization mix was cooled to room temperature. The annealed primer-RNA was precipitated by adding 45 μl of absolute ethanol to the hybridization mix. Precipitation of the annealed primer-RNA was carried out in an ethanol-dry ice bath for 30 min. The hybridization mix was then centrifuged in a microcentrifuge at 14,000 rpm for 15 min at 4°C. After centrifugation, the primer-RNA pellet was washed twice with 70% ethanol. The primer-RNA pellet was then resuspended in 10 μl of 5× reverse transcription buffer, 5 μl of dithiothreitol, 0.5 μl of 10 mM dATP, 0.5 μl of 10 mM dTTP, 0.5 μl of 10 mM dCTP, 0.5 μl of 10 mM dGTP, 0.5 μl of Superscript II reverse transcriptase, and 32.5 μl of H2O. The primer extension reaction was carried out for 1 h at 42°C. The newly synthesized DNA and the RNA in the extension reaction were precipitated by adding 200 μl of absolute ethanol to the extension mixture. After precipitation in an ethanol-dry ice bath for 30 min, the newly synthesized DNA and the RNA in the solution were centrifuged in a microcentrifuge at 14,000 rpm for 15 min at 4°C. The nucleic acid pellet was resuspended in 10 μl of sequencing gel loading buffer. Before being loaded on the gel, the nucleic acid was denatured by heating in boiling water for 3 min. A sequencing ladder was generated from pWPC9 with the primer used in the primer extension experiments. The sequencing ladder and the DNA fragments obtained from the primer extension experiments were resolved in an 8% sequencing gel. After electrophoresis was complete, the sequencing gel was covered with Saran Wrap, and the gel was dried under vacuum for 1 h at 80°C. Exposure of the dried gel to an X-ray film to produce an autoradiograph was carried out at −70°C. The film was then processed in an automatic film processor.

Measurement of band intensities on autoradiographs.

The autoradiographs produced from Northern blots and from primer extension gels were scanned, and the images were analyzed by the gel plotting function of the image analysis software (NIH Image). After the background was subtracted, the integrals of areas under the peaks corresponding to the predominant bands in the autoradiographs were calculated.

Repetition of experiments.

Unless stated otherwise, all reported experiments were performed at least three times with essentially similar results.

RESULTS

Transcription of the E. coli clpP-clpX operon during carbon starvation.

To study the expression of the clpP-clpX operon, Northern blotting was performed to determine the sizes of the transcripts produced from the clpP-clpX operon in log phase and during carbon starvation. A culture of E. coli E103S bacteria in log phase was subjected to carbon starvation. A sample of bacteria was collected before the culture was starved. At 15 min after the onset of carbon starvation, another bacterial sample was collected. Total RNA from each bacterial sample was purified, and Northern blotting was performed to determine the sizes and the relative levels of the transcripts produced from the clpP-clpX operon. The radiolabeled probe used to detect the transcripts of the clpP-clpX operon was prepared by nick translation of PCR fragments of the clpP sequence between bp 380 and bp 975. This probe hybridizes specifically to the clpP sequence; it was used for all the Northern blots in this study, with one noted exception.

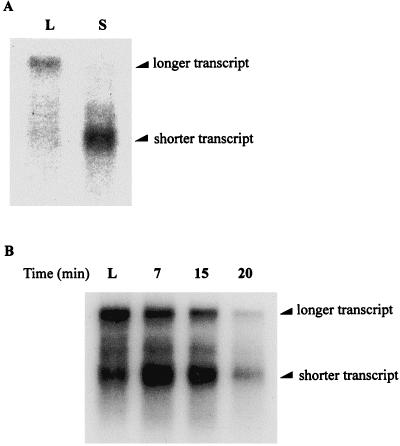

The results of Northern blotting are shown in Fig. 1A. Two differently sized transcripts are produced from the clpP-clpX operon. The longer transcript is the predominant transcript seen in log phase (Fig. 1A, lane L), but low levels of a shorter transcript are also sometimes evident (data not shown). After 15 min of carbon starvation, the level of the shorter RNA transcript increases significantly, and the level of the longer transcript decreases to an undetectable level (Fig. 1A, lane S).

FIG. 1.

(A) Northern blotting was performed to determine the sizes and relative levels of the transcripts produced from the clpP-clpX operon in E. coli E103S. RNA samples were prepared from a culture of E103S in log phase (lane L) and after 15 min of carbon starvation (lane S). The probe used in the Northern blotting hybridized specifically to the clpP sequence, not to the clpX sequence. This probe was used in all of the Northern blot experiments in this study. (B) Northern blotting was performed to analyze the clpP-clpX transcripts produced in E103S/pWPC9. Total RNA was extracted from E103S/pWPC9 in log phase (lane L) and after 7, 15, and 20 min of carbon starvation (lanes 7, 15, and 20, respectively).

To increase the signal strength detected on the Northern blot, E. coli E103S was transformed with pWPC9, obtained from S. Gottesman (21). pWPC9, a derivative of pBR322, carries a genomic DNA fragment which contains the entire clpP-clpX operon. Transcription of the clpP-clpX operon in E103S/pWPC9 was examined by Northern blotting. Since the copy number of pBR322 is about 15 to 20 copies per cell, it can be assumed that most of the signal shown on the Northern blot was derived from the expression of the clpP-clpX operon of pWPC9.

A culture of E103S/pWPC9 in log phase was subjected to carbon starvation. A bacterial sample was collected before the culture was subjected to carbon starvation, and additional bacterial samples were collected after 7, 15, and 20 min of carbon starvation. Total RNA was prepared from these bacterial samples, and Northern blotting was performed to determine the relative levels of the differently sized clpP-clpX transcripts. The results in Fig. 1B show that both the longer transcript and the shorter transcript are present in E103S/pWPC9 cells in log phase. The level of the shorter transcript with respect to the level of the longer transcript is low before the onset of carbon deprivation (Fig. 1B, lane L). Within 7 min after the start of carbon starvation, changes in the levels of the clpP-clpX transcripts can be observed (Fig. 1B, lane 7). The level of the longer transcript, the predominant transcript produced from the clpP-clpX operon in log phase, starts to decrease, and the level of the shorter transcript, present at a low level in log phase, increases dramatically. Between 7 and 15 min of carbon starvation, the level of the shorter transcript also starts to decrease (Fig. 1B, lanes 7 and 15). The level of the longer transcript continues decreasing during the same period of time. After 20 min of carbon starvation, the levels of both transcripts have decreased substantially (Fig. 1B, lane 20) so that very little signal hybridizing to the clpP probe can be seen.

To determine the sizes of both transcripts, RNA size markers, together with the RNA samples, were resolved in a glyoxal-agarose gel. The size of the longer transcript is estimated to be about 2,000 nucleotides; the size of the shorter transcript is estimated to be about 700 nucleotides (data not shown).

RpoH protein required for production of the shorter transcript.

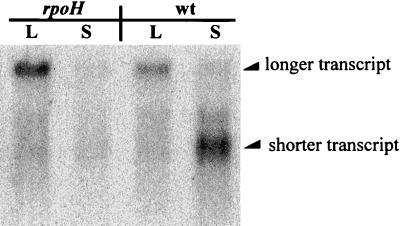

The ClpP protein is a heat shock protein (15), and the RpoH protein is required for the increase in the level of ClpP during heat shock (15). The RpoH protein is also involved in the induction of various stress-related proteins during entry into stationary phase (10, 11). The role of the RpoH protein in the increase in the level of the shorter transcript during carbon starvation was therefore determined. E. coli CAG15071 and CAG15137 were kindly provided by C. Gross. CAG15071 is an rpoH30::kan strain; CAG15137 is an rpoH+ strain otherwise isogenic to CAG15071. RNA was prepared from bacterial samples collected from cultures of CAG15071 and CAG15137 in log phase and after 15 min of carbon deprivation. Northern blotting was performed to determine the expression of the clpP-clpX operon in CAG15071 and CAG15137. The results of Northern blotting are shown in Fig. 2. CAG15137, the rpoH+ strain, shows changes in the relative amounts of the longer and shorter clpP-clpX transcripts similar to those seen in E103S during carbon starvation (Fig. 1A). The longer transcript is the predominant transcript produced from the clpP-clpX operon in the rpoH+ strain CAG15137 during log phase (Fig. 2, lane wt L); the shorter clpP-clpX transcript is predominant when CAG15137 is subjected to carbon deprivation (Fig. 2, lane wt S). CAG15071, the rpoH::kan strain, produces the longer transcript from the clpP-clpX operon in log phase (Fig. 2, lane rpoH L). CAG15071, however, does not accumulate the shorter transcript during carbon starvation (Fig. 2, lane rpoH S). The RpoH protein is the ς factor responsible for initiating transcription of genes involved in the heat shock response (29). The results with the rpoH mutant (Fig. 2) suggest that activation of the ς32-dependent promoter of the clpP-clpX operon is required for the increase in the level of the shorter transcript during carbon starvation.

FIG. 2.

Northern blotting was performed to analyze the transcripts produced from the clpP-clpX operon in E. coli strains CAG15137 (wt) and CAG15071 (rpoH) in log phase and during carbon starvation. Total RNA samples were prepared from the cultures in log phase (lanes labeled L) and after 15 min of carbon starvation (lanes labeled S).

clpP-clpX promoter utilization during carbon deprivation.

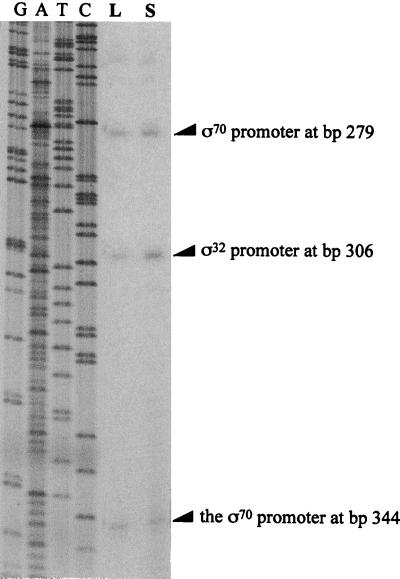

Primer extension was employed to determine which promoters of the clpP-clpX operon are used in log phase and during carbon starvation. Total RNA was extracted from the bacterial samples collected from cultures of E103S/pWPC9 in log phase and after 15 min of carbon starvation. The increase in the level of the shorter clpP-clpX transcript from starved E103S/pWPC9 cells was confirmed by Northern blotting (data not shown). Total RNA prepared from these bacterial samples was used for primer extension. The radiolabeled primer was annealed to the RNA sequence near the 5′ end of the clpP coding sequence, and the primers were then extended by reverse transcriptase. The DNA fragments extended from the annealed primer by reverse transcription were resolved in a sequencing gel. A sequencing ladder was generated from pWPC9 and the same primer was used in the primer extension experiments. The transcription initiation sites were determined by comparing the positions of DNA fragments to the sequencing ladder. The results of the primer extension experiments are shown in Fig. 3. Three transcription initiation sites, located at bp 279, bp 306, and bp 344, are evident. The transcription initiation sites for the two ς70-dependent promoters of the clpP-clpX operon are at bp 279 and bp 344 (21). The −10 region of the ς32-dependent promoter is thought to be located between bp 292 and bp 297 (8). Thus, bp 306 is probably the transcription initiation site of the ς32-dependent promoter of the clpP-clpX operon.

FIG. 3.

Activities of the ς70-dependent promoters and ς32-dependent promoter of the clpP-clpX operon analyzed by primer extension. Total RNA samples were prepared from a culture of E103S/pWPC9 in log phase (lane L) and after 15 min of carbon starvation (lane S). The same primer used for primer extension was also used to generate a sequencing ladder from pWPC9. The sequencing ladder and the DNA fragments from primer extension were resolved in an 8% sequencing gel. The initiation sites of the two ς70-dependent promoters are located at bp 279 and bp 344. The initiation site of the ς32-dependent promoter is located at bp 306.

The relative levels of transcription initiated from each promoter were measured. The percentages of the clpP-clpX transcripts initiated at each promoter in log phase and during carbon starvation are shown in Table 2. In log phase, transcription initiated at the two ς70-dependent promoters accounts for 75% of the total transcription of the clpP-clpX operon, and transcription initiated at the ς32-dependent promoter accounts for 25% of the total transcription of this operon. Thus, the ς32-dependent promoter of the clpP-clpX operon is used to a limited extent during logarithmic growth of E103S/pWPC9. Transcription initiated at the ς32-dependent promoter of the pWPC9 clpP-clpX operon increases from 25 to 43% during carbon starvation, and simultaneously, transcription from the ς70-dependent promoters decreases from 75 to 57%. Therefore, carbon deprivation leads to increased usage of the ς32-dependent promoter of the pWPC9 clpP-clpX operon.

TABLE 2.

Relative levels of transcription initiation from different clpP-clpX promoters

| Growth condition | % Transcription initiationa at:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| ς70 (bp 279) | ς32 (bp 306) | ς70 (bp 344) | |

| Log phase | 45 | 25 | 30 |

| Carbon starved | 35 | 43 | 22 |

The autoradiograph in Fig. 3 was scanned, and for each condition, the band intensity at each initiation site was determined as a fraction of the combined intensities of all three initiation sites.

Since the clpP-clpX transcripts appear to initiate at the three start sites shown in Table 2, the above experiments also show that the longer transcript (about 2,000 nucleotides) must include the entire clpP-clpX operon, whereas the shorter transcript (about 700 nucleotides) apparently terminates in the intergenic region between the clpP and clpX genes.

This conclusion is supported by experiments using a clpX-specific probe for Northern blots of carbon-starved E103S bacteria. This probe, which hybridized specifically to nucleotides 81 to 150 of the clpX coding sequence, detected the 2,000-nucleotide transcript but not the 700-nucleotide transcript in carbon-starved cells (data not shown). By 15 min after the initiation of carbon starvation, the 2,000-nucleotide transcript was nearly undetectable with this clpX probe, and no other transcripts appeared. These results support the conclusion that the 2,000-nucleotide transcript contains both the clpP and the clpX genes, whereas the 700-nucleotide transcript detected by the clpP probe contains the clpP but not the clpX sequence.

Activation of the ς32-dependent promoter and production of the shorter transcript.

The RpoH protein is required for the increase in the level of the ClpP protein during heat shock (15); furthermore, the results in Fig. 2 suggest that the increase in the level of the shorter transcript during carbon starvation requires the RpoH protein, presumably to activate the ς32-dependent promoter of the clpP-clpX operon. If activation of the ς32-dependent promoter were the only requirement for the production of the shorter transcript, subjecting the bacteria to heat shock should lead to an increase in the level of the shorter transcript. To determine the effect of heat shock on the transcription of the clpP-clpX operon, a bacterial sample was collected from a culture of E103S/pWPC9 in log phase. Additional bacterial samples were collected from cultures of E103S/pWPC9 15 min after the onset of heat shock at 42°C, 15 min after the onset of carbon starvation at 30°C, and 15 min after the onset of the carbon starvation and heat shock at 42°C. RNA was extracted from these bacterial samples, and Northern blotting was performed to determine the effects of the different conditions on the expression of the clpP-clpX operon in E103S/pWPC9. The results of Northern blotting are shown in Fig. 4. The band intensities of the shorter and longer transcripts in each sample on the blot were measured. The combined intensities of the shorter and the longer clpP-clpX transcripts of each sample were designated as 100%. The intensity of the shorter transcript as a percentage of the combined intensities was then determined for each sample. The results of these measurements are shown in Table 3. It appears that heat shock treatment does not change the ratio of the shorter transcript to the longer transcript (Table 3 and Fig. 4, lanes L and H). Similar to the results shown in Fig. 1, carbon starvation treatment leads to accumulation of the shorter transcript in E103S/pWPC9 (Fig. 4, lane S). The level of the shorter transcript as a percentage of the combined clpP-clpX transcripts increases from 13% in log phase and 16% during heat shock to 58% after 15 min of carbon starvation (Table 3). When E103S/pWPC9 bacteria are subjected to carbon starvation and to heat shock simultaneously, the shorter transcript is evident and the longer transcript is absent (Fig. 4, lane HS). Heat shock and/or carbon starvation treatment may transiently increase the total transcription of the clpP-clpX operon, but only carbon starvation leads to a relative increase in the production of the shorter transcript. These results suggest that activation of the ς32-dependent promoter of the clpP-clpX operon is not sufficient to increase the production of the shorter transcript.

FIG. 4.

Northern blotting performed to analyze the transcripts produced from the clpP-clpX operon in E103S/pWPC9 under different growth conditions. A total RNA sample was prepared from a culture of E103S/pWPC9 in log phase at 30°C (lane L). Additional RNA samples were prepared from the culture of E103S/pWPC9 after 15 min of heat shock at 42°C (lane H), after 15 min of carbon starvation at 30°C (lane S), and after 15 min of simultaneous heat shock and carbon starvation at 42°C (lane HS).

TABLE 3.

Relative levels of the shorter clpP-clpX transcripta

| Growth condition | Shorter transcript level (% of total) |

|---|---|

| Log phase | 13 |

| Heat shocked | 16 |

| Carbon starved | 58 |

| Heat shocked + carbon starved | 100 |

In addition to log phase, transcripts were examined after 15 min of heat shock at 42°C, after 15 min of starvation for carbon at 30°C, and after 15 min of simultaneous heat shock and carbon starvation at 42°C. The autoradiograph in Fig. 4 was scanned, and for each condition, the intensity of the band representing the shorter clpP-clpX transcript is shown as a percentage of the combined shorter and longer transcript bands.

Shorter transcript is degraded faster than the longer transcript.

Two of the various mechanisms that might lead to production of the shorter transcript from the clpP-clpX operon are (i) processive RNA processing, which removes nucleotides progressively from the 3′ end of the longer transcript to produce the shorter transcript, and (ii) premature termination of the longer transcript. As shown in Fig. 1, the level of the shorter transcript is unusually higher than the level of the longer transcript after 15 min of carbon starvation at 30°C. Therefore, if the first mechanism were active and the shorter transcript resulted from a progressive processing of the longer transcript, the half-life of the shorter transcript should be greater than or at least equal to the half-life of the longer precursor transcript. It would be unlikely for a progressive RNA-processing mechanism to be responsible for the relative increase in the level of the shorter transcript if this transcript had a shorter half-life than the longer transcript.

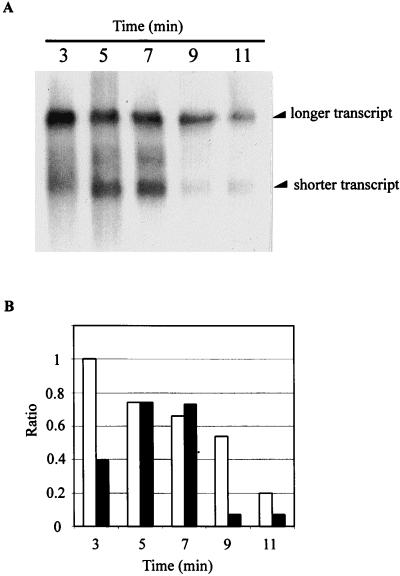

To estimate relative RNA half-lives, after 5 min of carbon starvation, rifampin was added to a culture of E103S/pWPC9 to a final concentration of 100 μg/ml. Total RNA was prepared from bacterial samples collected 3, 5, 7, 9, and 11 min after the onset of carbon starvation. Northern blotting was performed to determine the relative levels of the longer transcript and the shorter transcript at each time point. The results of Northern blotting are shown in Fig. 5A. After 5 min of carbon starvation, the levels of the longer and shorter transcripts appear to be nearly equal (Fig. 5A, lane 5). Since rifampin inhibits transcription initiation but not elongation, there is a latent period during which RNA polymerase will complete transcription of any nascent RNA chains before the effect of rifampin becomes evident. The results show no significant changes in the level of either transcript after 2 min of rifampin treatment, i.e., between 5 and 7 min after the onset of carbon starvation (Fig. 5A, lanes 5 and 7). During this period, the levels of both transcripts may have been maintained by newly completed transcripts. Between 7 and 9 min after the onset of carbon starvation, the level of the shorter transcript decreases to about 10% of the original level. During the same period of time, the longer transcript decreases only to about 70% of the original level (Fig. 5A, lanes 7 and 9). It appears, therefore, that the shorter transcript is degraded significantly more rapidly than the longer transcript during carbon starvation. This result, together with the results shown in Fig. 1 and 2, suggests that it is unlikely that the shorter transcript is produced by a progressive processing of the longer transcript.

FIG. 5.

(A) Northern blotting performed to determine the relative degradation rates of the transcripts produced from the clpP-clpX operon in E103S/pWPC9 during carbon deprivation. A culture of E103S/pWPC9 in log phase was subjected to carbon starvation. After 5 min of carbon starvation, rifampin was added to the starved culture to a final concentration of 100 μg/ml. The RNA samples used in Northern blotting were prepared from the culture of E103S/pWPC9 after 3, 5, 7, 9, and 11 min of carbon starvation (lanes 3, 5, 7, 9, and 11, respectively). (B) Relative levels of the shorter transcript and the longer transcript at various time points after rifampin treatment and the onset of carbon starvation were determined. The Northern blot shown in panel A was scanned, and the signal intensities of the shorter transcript and the longer transcript were measured. The signal intensity of the longer transcript after 3 min of carbon starvation was assigned a value of 1. The relative levels of the longer transcript and the shorter transcript in all other samples are shown as ratios of the band intensity to the signal intensity of the longer transcript after 3 min of carbon starvation. Open bars, longer transcript; solid bars, shorter transcript.

Relative levels of the shorter transcript and the longer transcript are affected by E. coli rpoB mutations.

If the production of the shorter RNA transcript from the clpP-clpX operon were due to premature termination of the longer transcript, the relative levels of the shorter and longer transcripts might be affected by changes in transcription termination efficiency. Therefore, the effects of rpoB mutations which alter transcription termination efficiency on the relative levels of the shorter and longer clpP-clpX transcripts were examined.

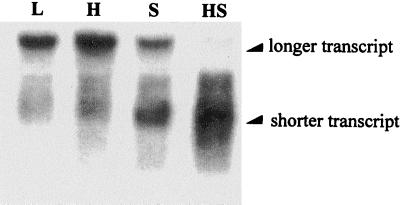

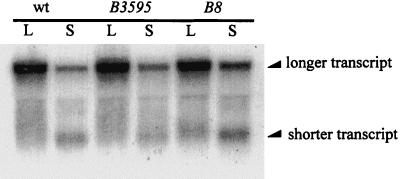

E. coli RFM443 and its isogenic strains RFM443 rpoB3595 and RFM443 rpoB8 were kindly provided by L. F. Liu. RNA polymerase carrying the rpoB3595 mutation has an increased transcription rate and a lowered transcription termination efficiency (28). In contrast, RNA polymerase carrying the rpoB8 mutation has a reduced transcription rate and an increased termination efficiency (12). The rpoB3595 and rpoB8 mutations were moved into E103S/pWPC9 by P1 transduction. The presence of the rpoB mutations in E103S/pWPC9 was confirmed by rifampin resistance and by heat sensitivity. Transcription of the clpP-clpX operon in E103S/pWPC9, E103S rpoB3595/pWPC9, and E103S rpoB8/pWPC9 was studied by Northern blotting. Cultures of E103S/pWPC9, E103S rpoB3595/pWPC9, and E103S rpoB/pWPC9 in log phase were subjected to carbon starvation for 15 min. Bacterial samples were collected before and after 15 min of carbon starvation. Total RNA was extracted from all bacterial samples, and Northern blotting was used to determine the ratio between the shorter transcript and the longer transcript in each sample. The results of Northern blotting are shown in Fig. 6. The band intensities of the shorter and longer transcripts in each sample on the blot were measured. The combined intensities of the shorter and the longer clpP-clpX transcripts of each sample were designated as 100%. The intensity of the shorter transcript as a percentage of the combined intensities was then determined for each sample. The results of these measurements are shown in Table 4. In log phase, E103S/pWPC9 and E103S rpoB3595/pWPC9 have relatively low percentages (7 and 0%, respectively) of the shorter transcript (Table 4 and Fig. 6, lanes wt L and B3595 L). On the other hand, the shorter transcript accounts for 21% of the combined clpP-clpX transcripts in E103S rpoB8/pWPC9 during logarithmic growth (Table 4). E103S rpoB8/pWPC9 thus accumulates more of the shorter transcript than does E103S/pWPC9 or E103S rpoB3595/pWPC9 during exponential growth (Fig. 6, lanes labeled L).

FIG. 6.

Northern blotting performed to analyze the sizes and levels of the clpP-clpX transcripts. Cultures of E103S/pWPC9 (wt), E103S rpoB3595/pWPC9 (B3595), and E103S rpoB8/pWPC9 (B8) were grown logarithmically and then subjected to carbon starvation. The RNA samples used in the Northern blot were prepared from the cultures during logarithmic growth (lanes L) and after 15 min of carbon starvation (lanes S).

TABLE 4.

Relative levels of the shorter clpP-clpX transcripta

| Strain | Condition | Shorter transcript level (% of total) |

|---|---|---|

| E103S/pWPC9 | Log phase | 7 |

| Starved | 38 | |

| E103S rpoB3595/pWPC9 | Log phase | 0 |

| Starved | 21 | |

| E103S rpoB8/pWPC9 | Log phase | 21 |

| Starved | 47 |

The autoradiograph in Fig. 6 was scanned, and for each strain and condition, the intensity of the band representing the shorter clpP-clpX transcript is shown as a percentage of the combined shorter and longer transcript band intensities.

During carbon starvation, E103S rpoB3595/pWPC9 accumulates less of the shorter transcript than does E103S/pWPC9 (Fig. 6, lanes wt S and B3595 S). The percentages of the shorter transcripts compared to the combined amounts of both transcripts in E103S rpoB3595/pWPC9 and E103S/pWPC9 during carbon starvation are 21 and 38%, respectively (Table 4). The shorter transcript in E103S rpoB8/pWPC9 during carbon starvation accounts for 47% of the clpP-clpX transcripts (Table 4), which is higher than that observed in E103S/pWPC9. Thus, RNA polymerase mutations that cause changes in transcription termination efficiency appear to affect the relative levels of the shorter and the longer clpP-clpX transcripts. These results are consistent with the hypothesis that premature transcription termination may play a role in the production of the shorter transcript.

DISCUSSION

Two different sizes of transcripts are produced from the clpP-clpX operon in E. coli. In log phase, the level of the longer transcript is higher than the level of the shorter transcript. During carbon starvation, the level of the shorter transcript increases significantly, whereas the level of the longer transcript decreases (Fig. 1). The accumulation of the shorter transcript during carbon starvation is dependent on the RpoH protein (Fig. 2). The RpoH protein is probably required to increase the activity of the ς32-dependent promoter of the clpP-clpX operon during carbon starvation (Fig. 3). Since the increase in the in vivo level of the ClpP protein following heat shock of an E. coli culture requires the RpoH protein (15), it seems that the ς32-dependent promoter of the clpP-clpX operon is also activated during heat shock. Nevertheless, activation of the ς32-dependent promoter by heat shock does not increase the relative level of the shorter transcript (Fig. 4). It appears that transcription initiated at the ς32-dependent promoter can produce either the shorter or the longer clpP-clpX transcript depending on factors associated with bacterial growth conditions.

Several observations lend support to the hypothesis that the shorter transcript is produced by premature termination of the longer clpP-clpX transcript. First, the shorter transcript is the most abundant clpP-clpX transcript shortly after the onset of carbon deprivation (Fig. 1). Second, the half-life of the shorter transcript is significantly less than that of the longer transcript during carbon starvation (Fig. 5). If the shorter transcript were produced by a processive degradation of the longer transcript, it would be unlikely for the level of the less-stable shorter transcript to be equal to or greater than that of the less-abundant longer transcript. Third, if the sorter transcript were produced by endonucleolytic cleavage of the longer transcript, a clpX probe might have detected a promoter-distal fragment of the longer transcript. A clpX-specific probe, however, failed to detect any transcript other than occasional trace amounts of the longer transcript by 15 min after the onset of carbon deprivation. Fourth, the E. coli rpoB3595 mutant with lower transcription termination efficiency (28) has a lower relative level of the shorter transcript during carbon starvation than does the isogenic wild-type strain (Fig. 6). The E. coli strain carrying the rpoB8 mutation, which increases the termination efficiency of RNA polymerase (12), produces elevated amounts of the shorter transcript in log phase and in carbon-deprived cells. Thus, the relative level of the shorter transcript is altered by changes in the transcription termination efficiency of RNA polymerase. These results suggest that the shorter transcript may be produced by premature termination of the longer clpP-clpX transcript.

This suggestion is consistent with an unpublished experiment in which we used E. coli strains K37 (rho+ nusA+), K7314 (rho), and K7906 (rho nusA), obtained from D. Friedman. When starved for carbon, strain K37 produced a typical short transcript band when examined with the clpP probe. The rho strain, K7314, however, failed to produce a distinct short transcript band; rather, Northern blots of RNA from starved K7314 cells showed an exceedingly diffuse collection of clpP-clpX transcripts. The rho nusA strain, K7906, again showed a clear short transcript in response to carbon deprivation. Therefore, it seems that the rho and the nusA factors, known to be involved in transcription termination, may play a role in the production of the shorter clpP-clpX transcript in response to starvation for carbon.

The band produced by the shorter transcript of the rpoB8 mutant in log phase is slightly diffuse (Fig. 6, lane rpoB8 L), indicating that the sizes of the short transcript produced by the rpoB8 mutant are somewhat diverse. If the shorter transcript were produced by endonucleolytic cleavage of the longer transcript, the location of the cleavage site preferred by the RNase would not likely be changed in the rpoB8 mutant. On the other hand, the locations of transcription termination sites may spread across a length of RNA, especially when termination is dependent on the Rho factor (18, 19). The increased termination efficiency of RNA polymerase caused by the rpoB8 mutation might increase transcription termination at locations downstream of the termination sites normally used by wild-type RNA polymerase. Transcription termination at the terminator sites not used by the transcription apparatus in the wild-type E. coli strain may thus lead to the heterogeneity of the shorter transcript shown on the Northern blots as the diffuse band representing the shorter transcripts of the rpoB8 mutant in logarithmic growth.

Comparing the results from E. coli strains with and without plasmid pWPC9, it is apparent that the longer clpP-clpX transcript is still present in strains with pWPC9 15 min after the onset of carbon starvation, whereas strains without pWPC9 have very low, usually undetectable levels of the longer transcript after the same period of carbon starvation. The shorter clpP-clpX transcript, usually absent or present only at a very low level in strains without pWPC9 in logarithmic growth, is also consistently evident in logarithmically growing strains with pWPC9. These differences seen on Northern blots of strains with and without pWPC9 may be due to higher levels of clpP-clpX transcription in strains with pWPC9. The resulting stronger Northern blot signals may enable the detection of low levels of the clpP-clpX transcripts by autoradiography. It is, however, also possible that the increased copy number of the clpP-clpX operon in strains with pWPC9 may saturate the mechanism which controls the sizes of the transcripts produced from the clpP-clpX operon, leading to the differences in clpP-clpX transcription observed between strains with and without pWPC9.

The RpoS protein plays a central role in controlling the set of genes which are induced during stationary phase (16, 17, 20). The level of RpoS is affected by protein stability (17, 36). RpoS is degraded rapidly in E. coli during exponential phase, but degradation of RpoS is reduced in stationary phase. Degradation of the RpoS protein is dependent on both the RssB protein (24) and the ClpXP protease (26, 37). Loss of ClpXP protease activity extends the half-life of RpoS more than 15-fold; thus, the ClpXP protease appears to be responsible for most of the turnover of RpoS. Shortly after the onset of carbon starvation, the level of the shorter clpP-clpX transcript (which encodes the ClpP protein but not the ClpX protein) increases substantially and the level of the longer transcript decreases (Fig. 1). Assuming that the efficiency of translation of the sorter transcript is similar to that of the longer transcript, the ratio of the ClpP protein to the ClpX protein will increase due to the increased percentage of the shorter transcript in carbon-deprived cells. The level of the clpA transcript, on the other hand, increases after the onset of carbon starvation (data not shown). Since ClpP can form functional proteases with either ClpA or ClpX, during carbon starvation ClpP would be more likely to complex with ClpA than with ClpX. The presumed decrease in the level of the ClpXP protease associated with greater production of the shorter clpP-clpX transcript and decreased production of the longer transcript during carbon starvation may contribute to the stabilization of the RpoS protein after the onset of carbon starvation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aiba H, Adhya S, de Crombrugghe B. Evidence for two functional gal promoters in intact Escherichia coli cells. J Biol Chem. 1981;256:11905–11910. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ausubel F M. Current protocols in molecular biology. New York, N.Y: Greene Publication Associates and Wiley-Interscience Co.; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Damerau K, St. John A C. Role of Clp protease subunits in degradation of carbon starvation proteins in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:53–63. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.1.53-63.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gottesman S. Genetics of proteolysis in Escherichia coli. Annu Rev Genet. 1989;23:163–198. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.23.120189.001115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gottesman S, Clark W P, Maurizi M R. The ATP-dependent Clp protease of Escherichia coli: sequence of clpA and identification of a Clp-specific substrates. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:7886–7893. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gottesman S, Maurizi M R. Regulation by proteolysis: energy-dependent proteases and their targets. Microbiol Rev. 1992;56:592–621. doi: 10.1128/mr.56.4.592-621.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gottesman S, Clark W P, de Crecy-Lagard V, Maurizi M R. ClpX, an alternative subunit for the ATP-dependent Clp protease of Escherichia coli: sequence and in vivo activities. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:22618–22626. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gross C. Function and regulation of the heat shock proteins. In: Neidhardt F C, et al., editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 1996. pp. 1382–1399. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hwang B J, Woo K M, Goldberg A L, Chung C H. Protease Ti, a new ATP-dependent protease in Escherichia coli, contains protein-activated ATPase and proteolytic functions in distinct subunits. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:8727–8734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jenkins D E, Schultz J E, Matin A. Starvation-induced cross protection for H2O2 challenge in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:3910–3914. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.9.3910-3914.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jenkins D E, Auger E A, Matin A. Role of RpoH, a heat shock regulator protein, in Escherichia coli carbon starvation protein synthesis and survival. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:1992–1996. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.6.1992-1996.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jin D J, Gross C A. RpoB8, a rifampicin-resistant termination-proficient RNA polymerase, has an increased Km for purine nucleotides during transcription elongation. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:14478–14485. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Katayama Y, Gottesman S, Pumphrey J, Rudikoff S, Clark W P, Maurizi M R. The two-component, ATP-dependent Clp protease of Escherichia coli: purification, cloning, and mutational analysis of the ATP-binding component. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:15226–15236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Katayama Y, Kasahara A, Kuraishi H, Amano F. Regulation of activity of an ATP-dependent protease, Clp, by the amount of a subunit, ClpA, in the growth of Escherichia coli cells. J Bacteriol. 1990;108:37–41. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a123158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kroh H, Simon L. The ClpP component of ClpP protease is the ς32-dependent heat shock protein F21.5. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:6026–6034. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.10.6026-6034.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lange R, Hengge-Aronis R. Identification of a central regulator of stationary-phase gene expression in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:49–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb01825.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lange R, Hengge-Aronis R. The cellular concentration of the ςs subunit of RNA polymerase in Escherichia coli is controlled at the levels of transcription, translation and protein stability. Genes Dev. 1994;8:1600–1612. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.13.1600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lau L F, Roberts J W, Wu R. Transcription terminates at 1 tR1 in three clusters. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1982;79:6171–6175. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.20.6171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lau L F, Roberts J W, Wu R. RNA polymerase pausing and transcription release at the 1 tR1 terminator in vitro. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:9391–9397. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Loewen P C, Hengge-Aronis R. The role of the sigma factor ςs (KatF) in bacterial global regulation. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1994;48:53–80. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.48.100194.000413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maurizi M R, Clark W P, Katayama Y, Rudikoff S, Pumphrey J, Bowers B, Gottesman S. Sequence and structure of ClpP, the proteolytic component of the ATP-dependent Clp protease of Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:12536–12545. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maurizi M R, Clark W P, Kim S H, Gottesman S. ClpP represents a unique family of serine proteases. J Biol Chem, 1990;265:12546–12552. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McCann M P, Fraley C D, Matin A. The putative ς factor KatF is regulated posttranscriptionally during carbon starvation. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:2143–2149. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.7.2143-2149.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muffler A, Fischer D, Altuvia S, Storz G, Hengge-Aronis R. The response regulator RssB controls stability of the ςs subunit of RNA polymerase in Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 1996;15:1333–1339. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schweder T, Lee K H, Lomovskaya O, Matin A. Regulation of Escherichia coli starvation sigma factor (ςs) by ClpXP protease. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:470–476. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.2.470-476.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Silhavy T J, Berman M L, Enquist L W. Experiments with gene fusions. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sparkowski J, Das A. Simultaneous gain and loss of functions caused by a single amino acid substitution in the β subunit of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase: suppression of nusA and rho mutations and conditional lethality. Genetics. 1991;130:411–428. doi: 10.1093/genetics/130.3.411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Straus D B, Walter W A, Gross C A. The heat shock response of E. coli is regulated by changes in the concentration of sigma 32. Nature. 1987;329:348–351. doi: 10.1038/329348a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tanaka K, Takayanagi Y, Fujita N, Ishihama A, Takahashi H. Heterogeneity of the principal ς factor in Escherichia coli: the rpoS gene product, ς38, is a second principal ς factor of RNA polymerase in stationary-phase Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:3511–3515. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.8.3511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wawrzynow A, Wojtkowiak D, Marszalek J, Banecki B, Jonsen M, Graves B, Georgopoulos C, Zylicz M. The ClpX heat-shock protein of Escherichia coli, the ATP-dependent substrate specificity component of the ClpP-ClpX protease, is a novel molecular chaperone. EMBO J. 1995;14:1867–1877. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07179.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wickner S, Gottesman S, Skowyra D, Hoskins J, McKenney K, Maurizi M R. A molecular chaperone, ClpA, functions like DnaK and DnaJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:12218–12222. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.25.12218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wojtkowiak D, Georgopoulos C, Zylicz M. Isolation and characterization of ClpX, a new ATP-dependent specificity component of the Clp protease of Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:22609–22617. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Woo K M, Chung W J, Ha D B, Goldberg A L, Chung C H. Protease Ti from Escherichia coli requires ATP hydrolysis for protein breakdown but not for hydrolysis of small peptides. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:2088–2091. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yoo S J, Seol J H, Kang M S, Ha D B, Chung C H. clpX encoding an alternative ATP-binding subunit of protease Ti (Clp) can be expressed independently from clpP in Escherichia coli. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;203:798–804. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.2253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zgurskaya H I, Keyhan M, Matin A. The ςs level in starving Escherichia coli cells increases solely as a result of its increased stability, despite decreased synthesis. Mol Microbiol. 1997;24:643–651. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.3961742.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhou Y, Gottesman S. Regulation of proteolysis of the stationary-phase sigma factor RpoS. J Bacteriol. 1997;180:1154–1158. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.5.1154-1158.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]