Abstract

Spirochete periplasmic flagella (PFs), including those from Brachyspira (Serpulina), Spirochaeta, Treponema, and Leptospira spp., have a unique structure. In most spirochete species, the periplasmic flagellar filaments consist of a core of at least three proteins (FlaB1, FlaB2, and FlaB3) and a sheath protein (FlaA). Each of these proteins is encoded by a separate gene. Using Brachyspira hyodysenteriae as a model system for analyzing PF function by allelic exchange mutagenesis, we analyzed purified PFs from previously constructed flaA::cat, flaA::kan, and flaB1::kan mutants and newly constructed flaB2::cat and flaB3::cat mutants. We investigated whether any of these mutants had a loss of motility and altered PF structure. As formerly found with flaA::cat, flaA::kan, and flaB1::kan mutants, flaB2::cat and flaB3::cat mutants were still motile, but all were less motile than the wild-type strain, using a swarm-plate assay. Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and Western blot analysis indicated that each mutation resulted in the specific loss of the cognate gene product in the assembled purified PFs. Consistent with these results, Northern blot analysis indicated that each flagellar filament gene was monocistronic. In contrast to previous results that analyzed PFs attached to disrupted cells, purified PFs from a flaA::cat mutant were significantly thinner (19.6 nm) than those of the wild-type strain and flaB1::kan, flaB2::cat, and flaB3::cat mutants (24 to 25 nm). These results provide supportive genetic evidence that FlaA forms a sheath around the FlaB core. Using high-magnification dark-field microscopy, we also found that flaA::cat and flaA::kan mutants produced PFs with a smaller helix pitch and helix diameter compared to the wild-type strain and flaB mutants. These results indicate that the interaction of FlaA with the FlaB core impacts periplasmic flagellar helical morphology.

The spirochetes are a phylogenetically and morphologically unique group of bacteria (42). This phylum contains not only many medically important species such as Treponema pallidum and Borrelia burgdorferi but others that are commensal with arthropods such as termites and some that are free-living and reside in soil and water (5, 17, 28, 42). The distinctive spirochete structure has been characterized in detail. Outermost is a membrane sheath, and within this sheath is the cell cylinder and periplasmic flagella (PFs). The PFs reside between the outer membrane sheath and cell cylinder in the periplasmic space. Each PF is subterminally attached to one end of the cell cylinder. Several lines of evidence indicate that the PFs are directly involved in spirochete motility and that these organelles rotate in a manner similar to that of flagella of other bacteria (6, 8, 30). The size of the spirochete, the number of PFs attached at each end of the cell cylinder, and whether the PFs overlap in the center of the cell vary from species to species (5).

The protein composition of PFs is complex (see 29 for recent review). In contrast to the flagella of most bacterial species, PFs are comprised of two classes of proteins termed FlaA and FlaB (3, 8, 39). PFs consist of one to two FlaA proteins and three to four FlaB proteins. B. burgdorferi is an exception, as this species has one FlaA protein and only one FlaB protein (11, 14). These proteins share immunological and sequence similarity within a given class but not between classes. In addition, these classes show extensive conservation within the spirochete phylum (3, 8, 9, 14, 26, 33, 39, 40, 47, 52). Nucleotide sequence data and N-terminal amino acid sequence information indicate that FlaA is likely to be secreted into the periplasmic space via the general secretory pathway (4, 39, 40, 43). In contrast, FlaB proteins have significant homology to flagellin of other bacteria in the N-terminal and C-terminal regions. These proteins are not cleaved at the N terminus and are most likely secreted into the periplasmic space by a type-III secretion system (3, 8, 39, 40).

The structure of the spirochete PF is atypical compared to the flagella of other bacteria. In fact, it is among the most complex of bacterial flagellar filaments so far studied (8). PFs consist of a core surrounded by a protein sheath (18, 38, 52). The intact PF has a diameter of 18 to 25 nm and a core of approximately 11 to 16 nm in diameter (18, 38, 52). Several lines of evidence indicate that FlaA comprises the sheath and that the several FlaB proteins form the core. The evidence includes immunoelectron microscopy of PFs from Spirochaeta aurantia, Leptospira interrogans, and Brachyspira (formerly Serpulina, Treponema) hyodysenteriae (3, 26, 31, 52), partially disrupted cells of T. pallidum analyzed by electron microscopy and Western blot analysis (9), and analysis of T. pallidum purified PFs by a Western blotting method termed epitope bridging (2).

The function of the individual PF proteins is poorly understood, as gene transfer systems have only recently been established for spirochetes so that specific genes can be inactivated (19, 30, 49, 51). Recently, Rosey et al., using allelic exchange mutagenesis, inactivated two PF filament genes of the spirochete B. hyodysenteriae, the etiological agent of swine dysentery (44, 45). This spirochete has approximately eight to nine PFs subterminally attached at each end (5). Based on Western blot analysis of lysed cells, the PFs were reported to be comprised of a FlaA protein that migrated as a doublet and three FlaB proteins designated FlaB1, FlaB2, and FlaB3 (44). The flaA and flaB1 mutants were found to remain motile but were less virulent for mice than the wild-type strain, and their swimming behavior appeared altered (22, 44). In addition, using electron microscopic analysis of disrupted whole cells revealed that the diameter of the attached PFs of the flaA mutants were identical to that of the wild-type strain (44, 45). These latter results are in conflict with the model that FlaA comprises the PF sheath. In the work reported here, we constructed the additional mutants flaB2 and flaB3 and analyzed their purified PFs and those from the previous mutants in detail. We show that inactivation of one fla gene specifically inhibited the incorporation of the encoded protein into the assembled PF. In addition, we reexamined the PF diameter of the mutants and wild-type strain and made comparisons. Finally, because little is known about how each protein influences filament morphology, we examined the PFs of the wild type and mutants by high-magnification dark-field microscopy. We show that FlaA influenced the helical shape of the assembled PFs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and culture conditions.

Escherichia coli, Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium LT2, and B. hyodysenteriae B204 and derived mutant strains are listed in Table 1. For convenience, the flaA1 gene (and its encoded protein) described by Rosey et al. (44) is referred to as flaA, as no other FlaA proteins have been detected in both analyses. E. coli and S. enterica serovar Typhimurium strains were grown in Luria Bertani medium or 2YT medium (35). B. hyodysenteriae cells were cultured in a Coy chamber using a premixed gas mixture of 90% N2 with 10% CO2 at 38°C. The equilibrated chamber contained 1 to 2% O2 (measured with a model 3100 oxygen sensor [Biosystems, Inc., Middlefield, Conn.]) which is optimal for B. hyodysenteriae (50). B. hyodysenteriae cells were grown in brain heart infusion broth supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (BHI-FBS) (44). Kanamycin (200 μg/ml) and/or chloramphenicol (20 μg/ml) were added to the media of appropriate mutant strains. Mutant strains were cloned by harvesting individual colonies from Trypticase soy agar plates supplemented with 5% whole bovine blood (TSAB) instead of the previously used sheep blood (44).

TABLE 1.

Bacteria, plasmids, and oligonucleotides

| Strains, plasmids, or primers | Description | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli | ||

| DH 5α | F−hsd17 supE44 thi-1 recA Δ(argF-lac)U169 φ80dlacZ ΔM15 λ− | Gibco-BRL |

| JM109 | endA1 recA1 gyrA96 thi hsdR17(rK mK+) relA1 supE44 λ− Δ(lac− proAB), (F′ traD36 proAB lacIqZΔM15) | Promega |

| B. hyodysenteriae | ||

| A120 | Wild-type B204 serotype 2 (ATCC 31212) | T. Stanton |

| A203 | Homologous recombination of pER199 at A201 chromosomal flaA locus | 44 |

| A204 | Homologous recombination of pER 158 at A201 chromosomal flaA locus | 44 |

| A205a | Homologous recombination of pER 141 at A120 chromosomal flaB1 locus | This study |

| A208 | Homologous recombination of pLNB2 at A120 chromosomal flaB2 locus | This study |

| A211 | Homologous recombination of pLNB3 at A120 chromosomal flaB3 locus | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pER187 | The NlaIV 852-bp cat gene cloned into pUC18 SmaI site | 45 |

| pTrep7 | pUC19 with a 2,350-bp HindIII chromosomal fragment containing flaB1 | 44 |

| pER141 | pTrep7 with kan gene replacing 589-bp BlgII fragment | 44 |

| pGEM-T | Ampr, PCR cloning vector | Promega |

| pGFB2 | pGEM-T with a 910-bp PCR fragment containing flaB2 gene | This study |

| pLNB2 | pGFB2 with cat gene replacing 345-bp EcoRI and HindIII fragment | This study |

| pGFB3 | pGEM-T with 1,185-bp PCR fragment containing flaB3 gene | This study |

| pLNB3 | pGFB3 with cat replacing 278-bp EcoRI and HindIII fragment | This study |

| DNA Primers | ||

| CHB1 | 5′-TTTGCCAAATAGGGACGG-3′ (flaB2, 5′+) | This study |

| CHB2 | 5′-TTACTGAATTAAACGACC-3′ (flaB2,3′−) | This study |

| CHB3: | 5′-TGGCAACTTCATATAGTCAG-3′ (flaB2, 5′+) | This study |

| CHB4: | 5′-AGTTTGCTATAAACGTAC-3′ (flaB2, 3′−) | This study |

| CHB5 | 5′-ATGTTATATTCTATTGTAC-3′ (flaB3, 5′ +) | This study |

| CHB6 | 5′-TACATCTATCTCACGCAT-3′ (flaB3, 3′−) | This study |

| CHB7 | 5′-AATAATGCCAAAAAGTC-3′ (flaB3, 5′+) | This study |

| CHB8 | 5′-TTGAGCTACTGTTTCTG-3′ (flaB3, 3′−) | This study |

| CAT1 | 5′-CTAATGAAGAAAGCAGACA-3′ (cat, 5′+) | This study |

| CAT2 | 5′-AACCTTCTTCAACTAACGG-3′ (cat, 3′−) | This study |

| DFB3 | 5′-ACNGGNAAYTCNATGAC-3′ (flaB3, 5′+) | This study |

| DRB3 | 5′-RTTYTCNGTNGCDATCAT-3′ (flaB3, 3′−) | This study |

| 16S-rRNA-1 | 5′-TTAAGCATGCAAGTCGAG-3′ (16S-rRNA, 5′+) | This study |

| 16S-rRNA-2 | 5′-TGATCTACGATTACTAG-3′ (16S-rRNA, 3′−) | This study |

DNA manipulation and PCR conditions.

Enzyme modification, subcloning, and transformation were carried out by standard procedures (35). B. hyodysenteriae chromosomal DNA was isolated as previously described (44). For amplification of target genes, the primer sequences, target loci, and binding sites for target genes are listed in Table 1. DNA amplifications were performed with Taq (Promega) or VentR polymerases. PCR was carried out at 95°C for 3 min, followed by 35 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 52°C for 1 min, 72°C for 2 to 3 min, and a final extension at 72°C for 8 min. The amplified DNA products were purified by using Qiagen PCR purification kits.

Electrotransformation of B. hyodysenteriae.

The preparation of competent cells of B. hyodysenteriae and electroporation were carried out essentially as previously described (44). All manipulations except centrifugations and electroporations were done in the Coy chamber, and all solutions were equilibrated at least 12 h in that chamber before use. Briefly, 1 liter of logarithmic-phase cells (5 × 107 to 4 × 108 cells/ml) was chilled on ice for 30 min, harvested at 9,600 × g for 10 min at 4°C, and resuspended in 100 ml of chilled wash buffer (15% glycerol–272 mM sucrose). After two washes in this buffer, cells were resuspended in 5 ml. original volume. The resulting cells (4.5 × 1010 cells/ml) were maintained on ice until use or stored at −80°C. Samples were prepared for electroporation by mixing 90 μl of electrocompetent cells and 1 μg of linearized plasmid DNA or PCR products in 10 μl in prechilled 0.1-cm cuvettes. Electroporation was carried out using the Bio-Rad Gene Pulsar II system at 1.5 kV, 25 μF, and 200 Ω resistance. Such conditions resulted in field strengths of 15 kV/cm with time constants between 3.8 and 4.5 ms. Following electroporation, 1.5 ml of prewarmed BHI-FBS was immediately added to cuvettes and transferred to a screw-cap tube (Falcon; 16 by 125 mm) containing a small stir bar. The recovered cells were incubated in the Coy chamber overnight with constant stirring. Chloramphenicol was added, and the cells were cultured for another 18 h. Approximately 0.5-ml samples were spread onto TSAB plates containing chloramphenicol. Colonies recovered after 5 to 7 days incubation were inoculated into 3 ml of BHI-FBS broth containing chloramphenicol.

DNA cloning techniques and screening of the genomic library.

Two degenerative primers were used to clone flaB3. The first primer was deduced from the variable region near the N-terminal amino acid sequence obtained by Edman degradation of the gel-extracted purified protein (C. Slaughter, Southwestern Medical School, Dallas, Tex.) (amino acid sequence, TGNSMT [Table 1, primer DFB3]). The second primer, which was directed to a conserved sequence near the C-terminal region common (amino acid sequence, MIATEN [Table 1 primer DRB3]) to both FlaB1 and FlaB2 of B. hyodysenteriae, was obtained using the PepTools alignment program. The 700-bp PCR product obtained after amplification was cloned into pGEM-T. Double-stranded DNA sequence analysis, BLAST comparisons with other FlaB proteins, and comparisons with peptide sequences obtained after trypsin digestion confirmed that the amplified DNA corresponded to flaB3. To obtain the entire flaB3 gene, a digoxigenin-labeled 615-bp PCR probe (random labeling kit [Boehringer Mannheim]) was used to screen a lambda ZAP II library (Stratagene) of B. hyodysenteriae DNA by standard methods (35). DNA from plasmids derived from positive plaques were further analyzed using Southern blotting and DNA sequencing. The GenBank Accession Number for B. hyodysenteriae flaB3 is AF241832.

Northern blot analysis.

Northern blot analysis was carried out using standard procedures (35). Approximately 500 ml of a culture of B. hyodysenteriae was harvested and washed with cold 0.067 M phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.5 [PBS]). Total RNA was isolated and purified using Qiagen RNeasy midikit. The samples were treated with RNase-free DNase I followed by a clean-up step using Qiagen RNeasy minikit. RNA samples were run in 1.2% formaldehyde agarose gels followed by transfer to Hybond-N+ membrane. Targeted genes were amplified by PCR and were labeled using the North 2South Biotin Random Prime kit (Pierce), and mRNA was detected using the Chemiluminescent Nucleic Acid Hybridization and Detection kit (Pierce).

PF purification.

PFs of B. hyodysenteriae were purified by a method similar to that used to purify PFs from Treponema denticola (47). One liter of a broth culture of late-logarithmic-phase cells (approximately 5 × 108 cells/ml) was harvested and centrifuged at 8,000 × g for 8 min at 4°C. The cell pellet was resuspended and washed twice with cold PBS. Following the second wash, the cells were resuspended in 90 ml of cold 0.1 M Tris buffer (pH 7.8 [T-buffer]). To remove the spirochete outer membrane sheath, 10 ml of a 10% (wt/vol) Triton X-100 solution was added dropwise with swirling and the mixture was incubated for 1 h at 37°C. The lysate was then centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C, and the pellet containing the PFs and cell cylinders was resuspended in 50 ml of T-buffer. The PFs were sheared from the cell cylinders by adding 8-ml aliquots to a 50-ml glass tube containing 1-mm glass beads and were vortexed vigorously for 1 min. After completion, the glass beads were rinsed with 10 ml of T-buffer, and the pooled mixture was centrifuged at 18,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C to remove cellular debris. The supernatant fluid was collected and centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 1 h at 4°C. The pellet, consisting of purified PFs, was suspended in either PBS containing 0.05% sodium azide and stored at 4°C or in T-buffer and stored at −20°C. Cesium chloride-purified PFs were obtained as follows: the pellet was suspended in 10 ml of PBS containing 5 g of cesium chloride and adjusted to a density of 1.270 g/cm2; after centrifugation at 180,000 × g at 15°C for 4 h, in a Beckman vertical TVi-65.2 rotor, the band containing the PFs (density, 1.30 g/cm3) was isolated and centrifuged at 2,000 × g at 4°C in a Centriprep 10 tube (Amicon) to concentrate the PFs; and dialysis in PBS to remove CsCl followed.

Gel electrophoresis and Western blotting.

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) was carried out as previously reported (14). The resolving gels contained 10% acrylamide and were stained with 0.25% Coomassie blue. Quantitation of proteins was achieved by using densitometry (Northern Light Precision Illuminator, model B90, with OPTIMUS 6.2 software program) on Coomassie blue-stained gels of purified PFs. Ten determinations were carried out, and each result is expressed as the mean plus or minus standard error of the mean (SEM). Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis was carried out using a pH range from 3 to 10 ampholytes (Investigator 2-D electrophoresis system) (39, 47). Precast gels were obtained from Genomic Solutions, Ann Arbor, Mich. The second-dimension gel was 10% acrylamide. For Western blotting, rabbit B. hyodysenteriae polyclonal FlaA and FlaB antisera were kindly provided by M. Jacques (University of Montreal, Quebec, Canada) (31). Monoclonal antibody to B. hyodysenteriae FlaB, which reacts with all three FlaB proteins, was kindly provided by G. Duhamel, University of Nebraska (10). Antisera directed to T. pallidum FlaA and to Treponema phagedenis FlaB proteins have been previously described (32, 33, 39). These latter antisera reacted with FlaA and FlaB proteins of B. hyodysenteriae, respectively. We found that the various antisera essentially yielded equivalent reactions. However, we found that the T. pallidum FlaA antiserum also reacted with FlaB1 of B. hyodysenteriae, and the T. phagedenis FlaB antiserum sometimes reacted with a nonflagellar protein of B. hyodysenteriae. Primary polyclonal antibodies were diluted to 1:5000, and the monoclonal antibodies were diluted to 1:3 million. Blots were developed by using horseradish peroxidase-conjugated second antibody with the ECL luminol assay (Amersham).

Dark-field microscopy.

PF morphology and cell motility were analyzed using dark-field microscopy (7). Briefly, PFs in PBS were suspended in approximately equal volumes of 1% methylcellulose 4000 (Fisher Scientific) also in PBS and observed using a 100× objective on a Leitz dark-field microscope with a DAGE-MTI model 72 charge-coupled device (CCD) camera at room temperature. Images were captured using a Sony Video Graphic printer UP-910. The helix pitch and helix diameter were measured directly from the video prints and are expressed as means plus or minus SEM; 25 PFs were measured for each strain. Significant differences were established using analysis of variance (ANOVA) and posthoc Tukey-Kramer tests. Flagella isolated from S. enterica serovar Typhimurium strain LT2 served as an internal control (7).

Both direct observation by microscopy and swarm plate assays were used to assay for motility. For microscopic assays, cell motility was determined by harvesting logarithmic-phase cells grown in BHI-FBS in a microcentrifuge and resuspending the pellet in prereduced PBS or saline (23). Motility was determined by using dark-field microscopy both in the presence and absence of 1% methylcellulose (47). Translational motility was specifically assayed for each mutant in these medium environments. For swarm plate assays, 4 μl of washed cells suspended in prereduced saline at a density of approximately 108 cells/ml was spotted on TSAB agar plates containing 0.3% agarose. After incubation for 36 h at 38°C in the reduced atmosphere, swarm diameters were determined.

Electron microscopy.

PFs and thin sections were examined by standard methodology. Approximately 5 μl of the filament suspensions were placed onto a copper grid (400 mesh) covered with a continuous carbon foil and blotted after 1 min using Whatman no. 40 filter paper. Heavy metal staining was performed using a 5-μl drop of 1% uranyl acetate that was blotted after 15 s. The grids were then allowed to air dry and were stored in a desiccated, sealed chamber. Images at a nominal magnification of ×60,000 were recorded onto Kodak SO-163 film using a Philips CM12 electron microscope operating at an accelerating voltage of 120 kV. Data were collected at room temperature, and low-dose techniques were not used. The diameters of the PFs were measured directly from the photographs using a caliper and are expressed as means plus or minus SEM. Significant differences were established using ANOVA and posthoc Tukey-Kramer tests. Not more than two measurements were made per filament, and at least 12 filaments were measured per sample. For the preparation of thin sections of B. hyodysenteriae cells, 5 to 10 ml of late-logarithmic-phase cells were centrifuged at 8,000 × g for 8 min at 4°C. Cells were fixed, block embedded, and stained as previously described (15, 30). Sections were viewed with a JEOL 1020 microscope at an accelerating voltage of 80 kV.

RESULTS

Composition of B. hyodysenteriae PFs.

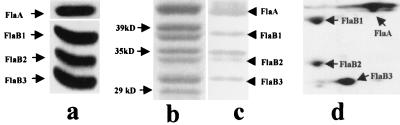

Previous analyses of B. hyodysenteriae PFs using SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis indicated that there were 1 to 2 FlaA proteins and 3 FlaB proteins (26, 44). In our analysis, we found a single wide band reacting with the FlaA antiserum (FlaA [44 kDa]) and 3 bands reacting with the FlaB antiserum (FlaB1 [37 kDa], FlaB2 [34 kDa], and FlaB3 [32 kDa]) (Fig. 1, lane a). Occasionally, the FlaA band appeared as a doublet by SDS-PAGE and Western blot. This FlaA doublet has also been observed by Rosey et al. (44). Proteins with molecular masses of 39, 35, and 29 kDa were consistently found in the PF preparations (Fig. 1, lane b), but these proteins failed to react with the FlaA or FlaB antisera. Similar findings of a 29- to 30-kDa protein in PF preparations have been reported for PFs of T. pallidum, T. phagedenis, and T. denticola (39, 47). Because the 39- and the 29-kDa proteins were not detected on CsCl purification of the PFs (Fig. 1, lane c), these two proteins are likely to be loosely associated with the PFs. Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis and Western blot analysis clearly resolved the wide band at 44 kDa into a smeared doublet (Figure 1, lane d). In contrast to T. phagedenis and T. denticola (39, 47), no additional major FlaB proteins were resolved with two-dimensional gel electrophoresis and Western blotting (Figure 1, lane d). The minor spot to the left of FlaB3 was analyzed in some detail. No differences were detected with this protein compared to FlaB3 by mass spectroscopy of digested peptides and N-terminal amino acid sequence analysis. In addition, mutations in the flaB3 gene led to its disappearance, indicating that the spot was encoded by flaB3. We consider that this spot is likely an artifact of two-dimensional gel electrophoresis.

FIG. 1.

Analysis of wild-type strain B204 periplasmic flagellar proteins. (a) Western blot analysis of PFs in a single dimension using B. hyodysenteriae polyclonal FlaA and monoclonal FlaB antisera. (b) Coomassie blue stain of purified PFs. (c) Coomassie blue stain of purified PFs after CsCl centrifugation, showing loss of the 39-kDa and 29-kDa proteins. (d) Western blot of a two-dimensional gel of purified periplasmic flagella, using polyclonal B. hyodysenteriae FlaA and T. phagedenis FlaB antisera.

Construction of flaB2 and flaB3 allele replacement vehicles and mutagenesis.

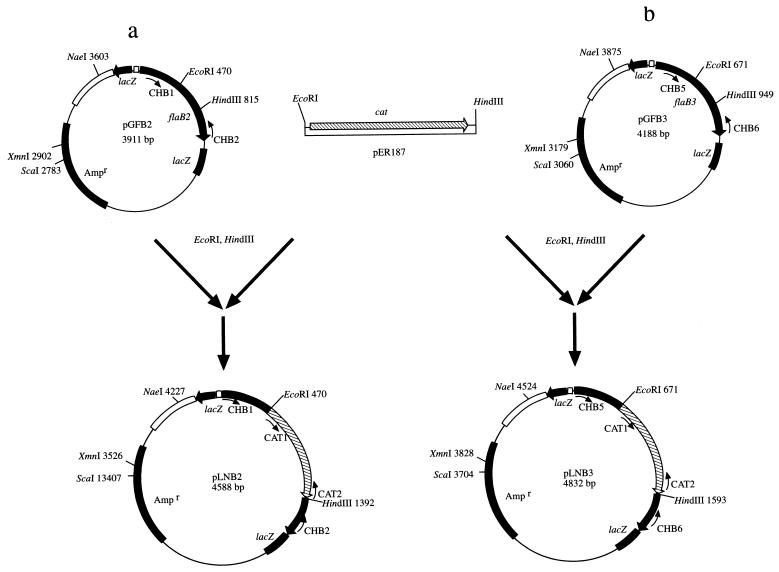

Besides the flaA::cat, flaA::kan, and flaB1::kan mutants already reported (44), we constructed and also analyzed flaB2::cat and flaB3::cat deletion mutants. The sequence of the flaB2 gene has recently been determined (25). To target flaB2 for allelic exchange mutagenesis, it was first amplified by PCR using primers CHB1/CHB2 (Table 1). The product obtained was cloned into pGEM-T to form plasmid pGFB2 (Fig. 2a). flaB2 was disrupted by replacement of an internal 345-bp EcoRI/HindIII fragment with a 922-bp cat cassette. The insert was flanked with 318-bp upstream and 246 bp downstream of B. hyodysenteriae DNA. The orientation of the insert was confirmed by PCR and DNA sequence analysis, and the resultant linearized plasmid pLNB2 was used for allelic-exchange mutagenesis.

FIG. 2.

Construction of plasmids pLNB2 and pLNB3. (a) Plasmid pGFB2, which contained the intact flaB2 gene, was cut with EcoRI and HindIII. The resulting 245-bp deletion was replaced by the purified cat gene from pER187, yielding pLNB2 (43). (b) Plasmid pGFB3, which contained the intact flaB3 gene, was cut with EcoRI and HindIII. The resulting 278-bp deletion was replaced by the purified cat gene from pER187, yielding pLNB3. The final linearized plasmids pYNB2 and pYNB3 were used for allelic-exchange mutagenesis.

The entire flaB3 gene was cloned and sequenced as described in Materials and Methods. Using the lambda ZAP II library and a labeled 615-bp flaB3 PCR-amplified product as probe, only one of several thousand plaques was positive. Sequencing the plasmid insert revealed an 840-bp open reading frame corresponding to a protein of 280 amino acids and a predicted mass of 30.5 kDa. This predicted size of FlaB3 approximates the 32-kDa mass estimated from SDS-PAGE analysis (Fig. 1). After extracting FlaB3 from gels and treating with trypsin, six internal peptides were sequenced by Edman degradation. The predicted amino acid sequence deduced from the gene sequence completely matched that of the obtained FlaB3 peptides (data not shown), thus confirming that the gene cloned was flaB3.

To construct the flaB3 allelic-exchange vehicle, a 1,185-bp fragment containing flaB3 and flanking DNA was amplified using primers CHB5/CHB6 (Table 1). The product obtained was cloned into pGEM-T to form the recombinant plasmid pGFB3 (Fig. 2b). Cloned flaB3 was disrupted by replacement of an internal 278-bp EcoRI/HindIII fragment with a 922-bp cat cassette. The insert was flanked by 621 bp upstream and 286 bp downstream of B. hyodysenteriae DNA. The resultant flaB3::cat pLNB3 plasmid was further characterized by PCR analysis and was used for allelic-exchange mutagenesis.

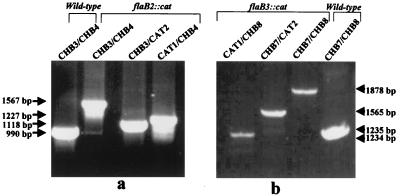

Both of the intact linearized donor plasmids, pLNB2 and pLNB3, were used to inactivate flaB2 and flaB3 by allelic-exchange mutagenesis. In addition, PCR products containing the flaB2::cat and the flaB3::cat inserts were also successful in activating flaB2 and flaB3. Following selection on plates with chloramphenicol, resistant mutants were screened by PCR with cat primers CAT1/CAT2. Those that were positive were further tested by PCR with flaB2 primers CHB3/CHB4 (Fig. 3a) and flaB3 primers CHB7/CHB8 (Fig. 3b). Each of these primers corresponded to flanking regions outside the input DNA. The flaB2::cat mutant (A208) yielded a 1,567-bp product rather than the wild-type 990-bp product. The products amplified by CHB3/CAT2 (1,227 bp) and CAT1/CHB4 (1,118 bp) suggested that cat recombined into the chromosomal flaB2 locus. For the flaB3::cat mutant (A211), the PCR product amplified by CHB7/CHB8 yielded a 1,878-bp rather than the wild-type 1,234-bp product. The products amplified by CHB7/CAT2 (1,565 bp) or CAT1/CHB8 (1,234 bp) suggested that cat was inserted into the chromosomal flaB3 locus. Products amplified by CHB3/CHB4 and CHB7/CHB8 were directly sequenced and were in complete agreement with homologous recombination of the input DNA occurring at flaB2 and flaB3 (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

PCR analysis of newly constructed flaB mutants compared with the wild-type strain B204. Ethidium bromide electrophoresis of DNA-amplified products using primers for analysis of (a) wild type and flaB2::cat mutant A208 and (b) flaB3::cat mutant A211 and wild type. PCR primers are listed in Table 1.

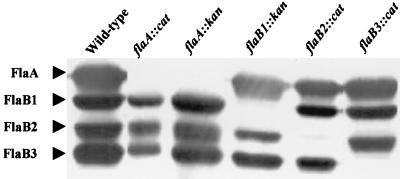

Mutants assemble PFs without the cognate gene product.

We analyzed the protein composition of the purified PFs. Previous results have shown that the deletion mutants flaA::cat, flaA::kan, and flaB1::kan had a loss of the corresponding protein as detected by Western blot analysis of whole-cell lysates. These mutants still assembled PFs and were motile (44). Because the protein composition of the purified PFs was not determined, a mutation in one fla gene could conceivably have impact on the assembly of the other FlaA and FlaB proteins in forming the PF. To further analyze the composition and structure of the PFs of these mutants, along with the newly constructed flaB2::cat and flaB3::cat mutants, the PFs of the mutants were purified and compared to the wild type. As with the previously described flaA::cat, flaA::kan, and flaB1::kan mutants, the flaB2::cat and flaB3::cat mutants were still motile as determined by dark-field microscopy. Western blot analysis of the PFs indicated that both flaA::cat and flaA::kan were deficient in the FlaA protein found in the wild type (Fig. 4). In addition, PFs from the flaB1::kan, flaB2::cat, and flaB3::cat mutants were specifically deficient in their respective cognate proteins. A similar pattern was obtained when whole-cell lysates were probed with the FlaA and FlaB antisera (data not shown). These results indicated that not only do all mutants fail to specifically express the mutant gene product but intact PFs are assembled from the remaining PF proteins. We also determined the ratios of the FlaB proteins relative to FlaA in the wild type and flaB1::kan and flaB2::cat mutant in purified PFs. We found that the wild type had a ratio of FlaB1 to FlaA of 0.42 ± 0.01, of FlaB2 to FlaA of 0.22 ± 0.04, and of FlaB3 to FlaA of 0.45 ± 0.07. In both the flaB1::kan and flaB2::cat mutants, these ratios did not markedly differ from those of the wild type. For example, in the flaB1::kan mutant, the ratio of FlaB2 to FlaA was 0.34 ± 0.04 and of FlaB3 to FlaA was 0.56 ± 0.04. Similar results were found with the flaB2::cat mutant (data not shown). These results suggest that the mutants did not compensate for a given flaB mutation by producing more of another FlaB protein.

FIG. 4.

Western blot analysis of purified PFs of mutants and wild type using B. hyodysenteriae FlaA and FlaB polyclonal antisera.

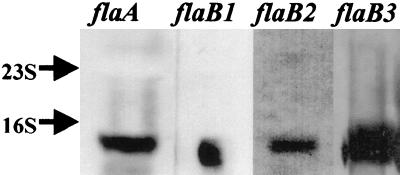

Northern blot analysis.

The analysis of the PF proteins indicated that a mutation in one gene did not have a polar effect on the expression of the other flaA and flaB genes. These results suggested that these genes are not part of an operon. To further understand the expression of these genes, we analyzed the transcripts of flaA, flaB1, flaB2, and flaB3 using Northern blot analysis (Fig. 5). Each of these genes was found to synthesize a relatively small-sized mRNA of approximately 1 kb. These results indicated that each of the flagellin genes is transcribed as a single gene transcript and are consistent with flaB genes being widely distributed throughout the B. hyodysenteriae strain B78T chromosome as found by Zuerner et al. (55).

FIG. 5.

Northern blot analysis of wild-type B204. Lanes indicate DNA probes used for hybridization.

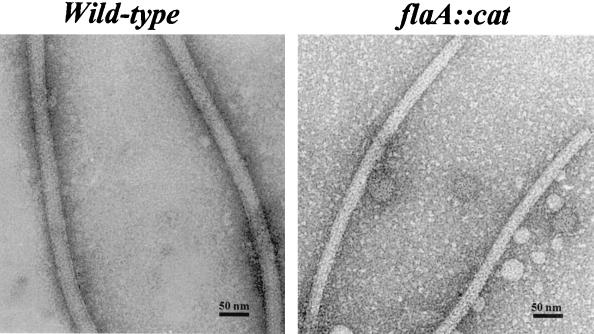

Ultrastructure of the wild-type and mutant PFs.

The PFs of the wild-type and flaA::cat and flaA::kan mutants have been reported to have the same diameter of approximately 15 nm (44, 45). These results, which were obtained by examining PFs from partially disrupted cells, are inconsistent with other evidence that FlaA forms a sheath around the FlaB core. Accordingly, we examined purified PFs of the wild type and mutants by negative staining and electron microscopy. The PFs of the wild type consisted of filaments of approximately 25.5 nm in diameter (Fig. 6, left panel). Occasionally, some PFs were seen that were obviously thinner. In addition, some appeared thicker at one region and thinner at another region. These thin PFs and the thin regions on the thicker PFs had diameters of approximately 18.4 nm. The diameters of the PFs from the flaB1::kan and flaB2::cat mutants were similar to that of the wild type (Fig. 6). In contrast, the diameters of the PFs of the flaA::cat mutant (19.6 ± 1.8 nm [Fig. 6, right panel) were significantly thinner than those of the wild type and flaB1::kan and flaB2::cat mutants (Fig. 6). In addition, the flaA::cat mutant PFs were similar in diameter to the occasional thin PFs seen in the wild type. Taken together, these genetic results support the immunoelectron microscopy findings that FlaA forms a sheath around the FlaB core in B. hyodysenteriae (26, 31). They also support a similar conclusion reached with other spirochete species PFs (2, 3, 9, 52).

FIG. 6.

Electron microscopic analysis of purified PFs from wild type and flaA::cat mutant A203. The PF diameters in nanometers (mean plus or minus SEM) of the wild type and mutants were as follows: wild type, 25.57 ± 0.23; flaA::cat, 19.62 ± 0.35; flaB1::kan, 24.37 ± 0.28; flaB2::cat, 24.02 ± 0.26; flaB3::cat, not determined. flaA::cat was significantly smaller than the wild type (P < 0.0001).

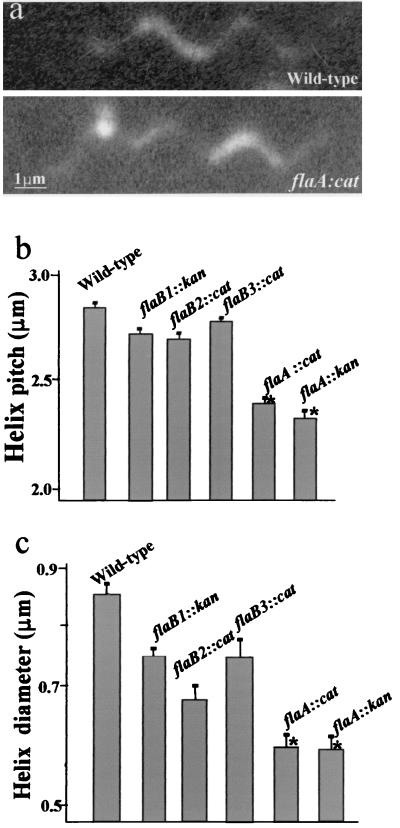

Periplasmic flagellar shape.

Bacterial flagella, as well as PFs from several spirochete species, have been shown to be helical as determined by high-magnification dark-field microscopy (6, 7, 34). Each spirochete species has been shown to have left-handed PFs with a distinct helix pitch, helix diameter, and handedness. Because the PFs consist of multiple proteins, it is not known what role each protein species plays with respect to overall filament morphology. Accordingly, we determined the handedness, helix pitch, and helix diameter of the wild-type and mutant PFs by dark-field microscopy (Fig. 7a through c). We found that the PFs of the wild-type and mutants were all left handed. The helix pitch of the wild type was 2.84 ± 0.09 μm with a helix diameter of 0.83 ± 0.04 μm. The PFs from the flaB1::kan, flaB2::cat, and flaB3::cat mutants were slightly smaller in helix pitch and diameter as compared to those of the wild type. In contrast, the PFs of both flaA::cat and flaA::kan mutants had a helix pitch and helix diameter significantly less than those of the wild type (Tukey's honestly significant difference (HSD), P < 0.0001). For example, the flaA::cat mutant A203 had a helix pitch of 2.43 ± 0.15 μm and a helix diameter of 0.61 ± 0.07 μm. These results indicated that mutants deficient in FlaA have PFs with a markedly altered helical shape.

FIG. 7.

Analysis of B. hyodysenteriae PF shape. (a) Dark-field micrographs of purified PFs from wild type and flaA::cat mutant. (b) Bar graph of helix pitch and (c) helix diameter of wild type and mutants. Data are means plus or minus SEM. ∗, Significance at 0.05 level.

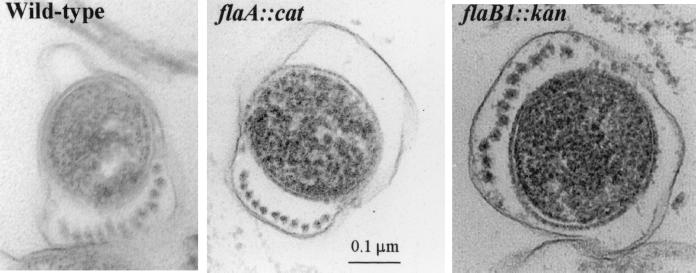

Number of PFs from wild type and mutants.

The location of the individual FlaB proteins in a given PF is unknown. A number of possible structural models have been postulated (44). One model states that the PFs are heterogenous within a given cell, but homogeneous with respect to a given filament (44). Thus, for example, some of the PFs in a given cell could be composed of FlaAFlaB1, while others could be composed of FlaAFlaB2 and FlaAFlaB3. If PFs from the mutants were heterogeneous within a given cell, the flaB1::kan, flaB2::cat, and flaB3::cat mutants should have fewer PFs than the wild type. To test for this possibility, we examined flaB1::kan and flaB2::cat mutant cells by thin-section electron microscopy. We found that the number of PFs per cell did not significantly differ from that of the wild type (Fig. 8). The mean number of PFs varied between by eight or nine PFs per cell. Because each mutant did not significantly produce more of the other FlaB proteins to compensate for its respective mutation (see above), it is unlikely that this number was achieved by overproducing one of the other FlaB proteins. These results are not consistent with the proposal that a given PF is composed of a single FlaB protein in association with FlaA; rather, the data suggest that a given PF contains FlaA and several different FlaB proteins (44).

FIG. 8.

Thin sections of wild type and flaA::cat and flaB1::kan mutants. flaB2::cat was similar (data not shown), and flaB3::cat was not determined. The mean numbers of PFs per cell were between 8 and 9 for the wild type and mutants.

Motility of wild type and mutants.

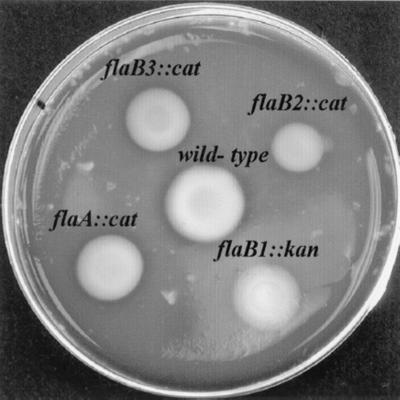

Rosey et al. (44) previously reported that flaA::cat, flaA::kan, and flaB1::kan mutants were motile as determined by light microscopy, but the behavior of these mutants as observed by dark-field microscopy appeared different than that of the wild type. We found that these mutants, along with the newly obtained flaB2::cat and flaB3::cat mutant strains, could translate both in PBS and in PBS containing 1% methylcellulose as observed by dark-field microscopy. Thus, we found that inactivation of each of the genes which encode the major filament proteins still results in motile cells. Swarm plate assays were used to quantitatively assay motility. We found that the swarm diameters of the flaA::cat, flaA::kan, and flaB1::kan mutants were slightly less than that of the wild type (Fig. 9). These results support those of Rosey et al. that the motility of the mutants was altered (44). The newly obtained flaB2::cat and flaB3::cat mutants also showed smaller swarms than that of the wild type. Of all the mutants analyzed, flaB2::cat consistently showed a smaller swarm diameter than the diameters of the other mutants. These results indicated that although all the mutants can still assemble PFs, each appears somewhat deficient in motility, with the flaB2::cat mutant having the most deficiency.

FIG. 9.

Swarm plate assay of wild type and PF mutants. Diameters of swarms (centimeters) after 36 h of incubation: wild type, 2.1; flaA::cat, 1.7; flaB1::kan, 1.7; flaB2::cat, 1.4; flaB3::cat, 1.6.

DISCUSSION

Spirochetes have historically been a difficult phylum of bacteria to study. These organisms generally require a rich medium for growth and have long generation times. Several important spirochete pathogens, including T. pallidum and many of the oral Treponema species, have yet to be continuously cultured (5, 42). Only in B. hyodysenteriae and B. burgdorferi has a gene exchange system been shown to occur by a mechanism other than via electroporation (19; D. Samuels, personal communication). Compared to the genetic techniques used to analyze function in other bacteria, the tools now available for spirochete gene analysis are relatively primitive. The experiments reported here exploit the use of electroporation and allelic-exchange mutagenesis as a means to better understand the function of specific PF genes in B. hyodysenteriae. Because the structure and composition of the PFs of B. hyodysenteriae (13, 25–27) are so similar to those of T. denticola (47), L. interrogans (37, 52), S. aurantia (3, 4, 8, 41), and the more intractable T. pallidum (39, 40), the results obtained are likely to be relevant to these other species.

Motility is likely to be an important virulence factor for spirochetes (22, 45, 48). These organisms can swim through gel-like viscous media, such as connective tissue, which inhibit the motility of most bacteria (1, 16, 24, 46). B. burgdorferi penetrates the skin after a tick bite, and T. pallidum, L. interrogans, and B. burgdorferi infect many tissues of the host, even the eye, which other organisms fail to invade (20, 24). In addition, genomic analyses of B. burgdorferi and T. pallidum indicate that these spirochetes have at least 4 to 6% of their genes dedicated to motility and chemotaxis (11, 12). This relatively large percent of the genetic material aimed toward these functions reinforces the role of motility and chemotaxis in the survival of these bacteria within the hosts that they parasitize and in which, in some cases, they cause disease. For B. hyodysenteriae, mutants which have altered PFs and motility also are less virulent in mice, which again reinforces the role of motility for certain species of spirochetes (22, 45).

In our analysis of the PF proteins of B. hyodysenteriae, we found that two-dimensional gel electrophoresis enhanced resolution of the FlaA PF proteins, but no new FlaB proteins were detected. FlaA appeared as a smeared doublet of approximately 43 to 44 kDa. Our results are similar to those of Rosey et al., who found a FlaA doublet of approximately the same molecular masses (44). One of the proteins in the doublet is likely to be a precursor to the other rather than each being encoded by a separate gene. Specifically, inactivation of flaA inhibits synthesis of both proteins in the doublet. Because Northern blot analysis indicates that flaA is synthesized as a monocistronic mRNA, it is unlikely that the results obtained are related to a polar effect on gene expression. The broad band observed for FlaA may be related to post-translational modification. Along these lines, Li et al found that FlaA is likely to be glycosylated (31). Glycosylated proteins often appear smeared in two-dimensional gel electrophoresis. Our results differ from those of Koopman et al., who found two FlaA proteins with masses of 44 and 35 kDa (26). One possible explanation for this difference may be related to the strains tested; we used strain B204 as did Rosey et al. (44), whereas Koopman used strain C5 (26).

Our results, in conjunction with the previous results of Rosey et al. (44), indicate that mutants with single mutations in flaB1, flaB2, or flaB3 were still motile and could synthesize PFs. Moreover, based on the parameters measured, the morphology of the PFs was not markedly altered in the flaB mutants. Alignment of the deduced amino acid sequences of the three FlaB proteins shows between 37 and 51% identity, with the N-terminal region most conserved (data not shown). These findings, coupled with the mutational analysis, indicate that the FlaB proteins are at least somewhat redundant with respect to function. These results are analogous to flagella formation in Caulobacter, Helicobacter, and Campylobacter spp. Each of these species synthesizes multiple flagellin filament species, and inactivation of one of the encoding genes still results in the retention of motility and filament synthesis, although in each species the motility of the mutants is altered (21, 36, 54).

FlaA impacts the shape of the PFs as determined by measuring the helix pitch and helix diameter of the purified PFs. Because the helix pitch and diameter of the PFs of the flaA::cat and flaA::kan mutants were markedly less than those of the wild type, evidently the presence of FlaA results in an increase in helicity. It may be that the sheath structure per se influences the overall shape of the PFs. Along these lines, preliminary evidence with a double flaB mutant and with a fliG mutant indicate that the sheath can form a hollow tube independently of the core in B. hyodysenteriae (C. Li and N. W. Charon, unpublished data). Because bacterial flagella are often quasirigid and undergo helical transformations (34, 53), perhaps the sheath helps stabilize the FlaB helical core into one of these configurations for optimal thrust as it rotates between the outer membrane sheath and cell cylinder. We anticipate that future genetic experiments will allow us to determine the nature of the interaction of FlaA with the multiple FlaB proteins and how these proteins participate in achieving optimal cell motility.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank S. Humphrey, R. Macnab, and especially D. Yelton for helpful discussions; X. M. Gao for help in the construction of pLNB2; J. D. Ruby for help on periplasmic flagella purification methodolgy, G. Hobbs for help with statistics, S. Dodson for help in cloning flaB3, and D. Berry for assistance with electron microscopy. We also thank G. Duhamel, M. Jacques, and S. Norris for antisera, and R. Yancey for encouragement.

This research was supported by Public Health Service grant DE12046, and by USDA grant 95-37204-2132.

REFERENCES

- 1.Berg H C, Turner L. Movement of microorganisms in viscous environments. Nature (London) 1979;278:349–351. doi: 10.1038/278349a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blanco D R, Champion C I, Miller J N, Lovett M A. Antigenic and structural characterization of Treponema pallidum (Nichols strain) endoflagella. Infect Immun. 1988;56:168–175. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.1.168-175.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brahamsha B, Greenberg E P. A biochemical and cytological analysis of the complex periplasmic flagella from Spirochaeta aurantia. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:4023–4032. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.9.4023-4032.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brahamsha B, Greenberg E P. Cloning and sequence analysis of flaA, a gene encoding a Spirochaeta aurantia flagellar filament surface antigen. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:1692–1697. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.3.1692-1697.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Canale-Parola E. The Spirochetes. In: Krieg N R, Holt J G, editors. Bergey's manual of systematic bacteriology. Baltimore, Md: The Williams & Wilkins Co.; 1984. pp. 38–70. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Charon N W, Goldstein S F, Block S M, Curci K, Ruby J D, Kreiling J A, Limberger R J. Morphology and dynamics of protruding spirochete periplasmic flagella. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:832–840. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.3.832-840.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Charon N W, Goldstein S F, Curci K, Limberger R J. The bent-end morphology of Treponema phagedenis is associated with short, left-handed periplasmic flagella. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:4820–4826. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.15.4820-4826.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Charon N W, Greenberg E P, Koopman M B, Limberger R J. Spirochete chemotaxis, motility, and the structure of the spirochetal periplasmic flagella. Res Microbiol. 1992;143:597–603. doi: 10.1016/0923-2508(92)90117-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cockayne A, Bailey M J, Penn C W. Analysis of sheath and core structures of the axial filament of Treponema pallidum. J Gen Microbiol. 1987;133:1397–1407. doi: 10.1099/00221287-133-6-1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fisher L N, Duhamel G E, Westerman R B, Mathiesen M R. Immunoblot reactivity of polyclonal and monoclonal antibodies with periplasmic flagellar proteins FlaA1 and FlaB of porcine Serpulina species. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1997;4:400–404. doi: 10.1128/cdli.4.4.400-404.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fraser C M, Casjens S, Huang W M, Sutton G G, Clayton R, Lathigra R, White O, Ketchum K A, Dodson R, Hickey E K, Gwinn M, Dougherty B, Tomb J F, Fleischmann R D, Richardson D, Peterson J, Kerlavage A R, Quackenbush J, Salzberg S, Hanson M, van Vugt R, Palmer N, Adams M D, Gocayne J. Genomic sequence of a Lyme disease spirochaete, Borrelia burgdorferi. Nature. 1997;390:580–586. doi: 10.1038/37551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fraser C M, Norris S J, Weinstock C M, White O, Sutton G G, Dodson R, Gwinn M, Hickey E K, Clayton R, Ketchum K A, Sodergren E, Hardham J M, McLeod M P, Salzberg S, Peterson J, Khalak H, Richardson D, Howell J K, Chidambaram M, Utterback T, McDonald L, Artiach P, Bowman C, Cotton M D. Complete genome sequence of Treponema pallidum, the syphilis spirochete. Science. 1998;281:375–388. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5375.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gabe J D, Chang R-J, Slomiany R, Andrews W H, McCaman M T. Isolation of extracytoplasmic proteins from Serpulina hyodysenteriae B204 and molecular cloning of the flaB1 gene encoding a 38 kilodalton flagellar protein. Infect Immun. 1995;63:142–148. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.1.142-148.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ge Y, Li C, Corum L, Slaughter C A, Charon N W. Structure and expression of the FlaA periplasmic flagellar protein of Borrelia burgdorferi. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:2418–2425. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.9.2418-2425.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldstein S F, Buttle K F, Charon N W. Structural analysis of the Leptospiraceae and Borrelia burgdorferi using high voltage electron microscopy. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:6539–6545. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.22.6539-6545.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Greenberg E P, Canale-Parola E. Relationship between cell coiling and motility of spirochetes in viscous environments. J Bacteriol. 1977;131:960–969. doi: 10.1128/jb.131.3.960-969.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harwood C S, Canale-Parola E. Ecology of spirochetes. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1984;38:161–192. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.38.100184.001113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hovind-Hougen K. Determination by means of electron microscopy of morphological criteria of value for classification of some spirochetes, in particular treponemes. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand Sect B Suppl. 1976;255:1–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Humphrey S B, Stanton T B, Jensen N S, Zuerner R L. Purification and characterization of VSH-1, a generalized transducing bacteriophage of Serpulina hyodysenteriae. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:323–329. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.2.323-329.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson R C, Marek N, Kodner C. Infection of Syrian hamsters with lyme disease spirochetes. J Clin Microbiol. 1984;20:1099–1101. doi: 10.1128/jcm.20.6.1099-1101.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Josenhans C, Labigne A, Suerbaum S. Comparative ultrastructural and functional studies of Helicobacter pylori and Helicobacter mustelae flagellin mutants: both flagellin subunits, FlaA and FlaB, are necessary for full motility in Helicobacter species. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:3010–3020. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.11.3010-3020.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kennedy M J, Rosey E L, Yancey R J., Jr Characterization of flaA− and flaB− mutants of Serpulina hyodysenteriae: both flagellin subunits, FlaA and FlaB, are necessary for full motility and intestinal colonization. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;153:119–128. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb10472.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kennedy M J, Yancey R J., Jr Motility and chemotaxis in Serpulina hyodysenteriae. Vet Microbiol. 1996;49:21–30. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(95)00174-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kimsey R B, Spielman A. Motility of lyme disease spirochetes in fluids as viscous as the extracellular matrix. J Infect Dis. 1990;162:1205–1208. doi: 10.1093/infdis/162.5.1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koopman M B, Baats E, de Leeuw O S, Van der Zeijst B A, Kusters J G. Molecular analysis of a flagellar core protein gene of Serpulina (Treponema) hyodysenteriae. J Gen Microbiol. 1993;139:1701–1706. doi: 10.1099/00221287-139-8-1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koopman M B, Baats E, van Vorstenbosch C J, Van der Zeijst B A, Kusters J G. The periplasmic flagella of Serpulina (Treponema) hyodysenteriae are composed of two sheath proteins and three core proteins. J Gen Microbiol. 1992;138:2697–2706. doi: 10.1099/00221287-138-12-2697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koopman M B H, de Leeuw O S, Van der Zeijst B A, Kusters J G. Cloning and DNA sequence analysis of a Serpulina (Treponema) hyodysenteriae gene encoding a periplasmic flagellar sheath protein. Infect Immun. 1992;60:2920–2925. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.7.2920-2925.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leadbetter J R, Schmidt T M, Graber J R, Breznak J A. Acetogenesis from H2 plus CO2 by spirochetes from termite guts. Science. 1999;283:686–689. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5402.686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li C, Motaleb M A, Sal M, Goldstein S F, Charon N W. Spirochete periplasmic flagella and motility. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol. 2000;2:345–354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li H, Ruby J, Charon N, Kuramitsu H. Gene inactivation in the oral spirochete Treponema denticola: construction of a flgE mutant. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:3664–3667. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.12.3664-3667.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li Z, Dumas F, Dubreuil D, Jacques M. A species-specific periplasmic flagellar protein of Serpulina (Treponema) hyodysenteriae. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:8000–8007. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.24.8000-8007.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Limberger R J, Charon N W. Treponema phagedenis has at least two proteins residing together on its periplasmic flagella. J Bacteriol. 1986;166:105–112. doi: 10.1128/jb.166.1.105-112.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Limberger R J, Charon N W. Antiserum to the 33,000-dalton periplasmic-flagellum protein of “Treponema phagedenis” reacts with other treponemes and Spirochaeta aurantia. J Bacteriol. 1986;168:1030–1032. doi: 10.1128/jb.168.2.1030-1032.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Macnab R M. Flagella and motility. In: Neidhardt F C, Curtiss III R, Ingraham J L, Lin E C C, Low K B, Magasanik B, Reznikoff W S, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 1996. pp. 123–145. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maniatias T, Fritsch E F, Sambrook J. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Minnich S A, Ohta N, Taylor N, Newton A. Role of the 25-, 27-, and 29-kilodalton flagellins in Caulobacter crescentus cell motility: method for construction of deletion and Tn5 insertion mutants by gene replacement. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:3953–3960. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.9.3953-3960.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mitchison M, Rood J I, Faine S, Adler B. Molecular analysis of a Leptospira borgpetersenii gene encoding an endoflagellar subunit protein. J Gen Microbiol. 1991;137:1529–1536. doi: 10.1099/00221287-137-7-1529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nauman R K, Holt S C, Cox C D. Purification, ultrastructure, and composition of axial filaments from Leptospira. J Bacteriol. 1969;98:264–280. doi: 10.1128/jb.98.1.264-280.1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Norris S J, Charon N W, Cook R G, Fuentes M D, Limberger R J. Antigenic relatedness and N-terminal sequence homology define two classes of major periplasmic flagellar proteins of Treponema pallidum subsp. pallidum and Treponema phagedenis. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:4072–4082. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.9.4072-4082.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Norris S J Treponema pallidum Polypeptide Research Group. Polypeptides of Treponema pallidum: progress toward understanding their structural, functional, and immunologic roles. Microbiol Rev. 1993;57:750–779. doi: 10.1128/mr.57.3.750-779.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Parales J, Jr, Greenberg E P. N-terminal amino acid sequences and amino acid compositions of the Spirochaeta aurantia flagellar filament polypeptides. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:1357–1359. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.3.1357-1359.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Paster B J, Dewhirst F E, Weisburg W G, Tordoff L A, Fraser G J, Hespell R B, Stanton T B, Zablen L, Mandelco L, Woese C R. Phylogenetic analysis of the spirochetes. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:6101–6109. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.19.6101-6109.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pugsley A P. The complete general secretory pathway in gram-negative bacteria. Microbiol Rev. 1993;57:50–108. doi: 10.1128/mr.57.1.50-108.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rosey E L, Kennedy M J, Petrella D K, Ulrich R G, Yancey R J., Jr Inactivation of Serpulina hyodysenteriae flaA1 and flaB1 periplasmic flagellar genes by electroporation-mediated allelic exchange. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:5959–5970. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.20.5959-5970.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rosey E L, Kennedy M J, Yancey R J., Jr Dual flaA1 flaB1 mutant of Serpulina hyodysenteriae expressing periplasmic flagella is severely attenuated in a murine model of swine dysentery. Infect Immun. 1996;64:4154–4162. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.10.4154-4162.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ruby J D, Charon N W. Effect of temperature and viscosity on the motility of the spirochete Treponema denticola. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1998;169:251–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1998.tb13325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ruby J D, Li H, Kuramitsu H, Norris S J, Goldstein S F, Buttle K F, Charon N W. Relationship of Treponema denticola periplasmic flagella to irregular cell morphology. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:1628–1635. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.5.1628-1635.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sadziene A, Thomas D D, Bundoc V G, Holt S C, Barbour A G. A flagella-less mutant of Borrelia burgdorferi: structural, molecular, and in vitro functional characterization. J Clin Invest. 1991;88:82–92. doi: 10.1172/JCI115308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Samuels D S, Mach K E, Garon C F. Genetic transformation of the Lyme disease agent Borrelia burgdorferi with coumarin-resistant gyrB. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:6045–6049. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.19.6045-6049.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stanton T B. Physiology of ruminal and intestinal spirochetes. In: Hampson D J, Stanton T B, editors. Intestinal spirochaetes in domestic animals and humans. Wallingford, United Kingdom: CAB Int.; 1997. pp. 7–45. [Google Scholar]

- 51.ter Huurne A A H M, van Houten M, Muir S, Kusters J G, Van der Zeijst B A M, Gaastra W. Inactivation of a Serpula (Treponema) hyodysenteriae hemolysin gene by homologous recombination: importance of this hemolysin in pathogenesis of S. hyodysenteriae in mice. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1992;92:109–114. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(92)90550-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Trueba G A, Bolin C A, Zuerner R L. Characterization of the periplasmic flagellum proteins of Leptospira interrogans. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:4761–4768. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.14.4761-4768.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yamashita I, Hasegawa K, Suzuki H, Vonderviszt F, Mimori-Kiyosue Y, Namba K. Structure and switching of bacterial flagellar filaments studied by X-ray fiber diffraction. Nat Struct Biol. 1998;5:125–132. doi: 10.1038/nsb0298-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yao R, Burr D H, Doig P, Trust T J, Niu H, Guerry P. Isolation of motile and non-motile insertional mutants of Campylobacter jejuni: the role of motility in adherence and invasion of eukaryotic cells. Mol Microbiol. 1994;14:883–893. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01324.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zuerner R L, Stanton T B. Physical and genetic map of the Serpulina hyodysenteriae B78T chromosome. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:1087–1092. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.4.1087-1092.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]