Abstract

The Toll-like receptor (TLR)4 is critical for the recognition of Gram-negative bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS) but in porcine peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) it may cooperate with other TLRs and lead to the production of inflammatory cytokines. Therefore, we analyzed TLR1–10 mRNA expression in porcine PBMCs stimulated with LPS over time (1–48 h) by using quantitative real-time PCR and cytokine proteins level by ELISA in culture supernatant. TLR1–10 mRNA was detectable in porcine PBMCs. When compared with the control (non-stimulated), TLR1 mRNA were increased (p < 0.05) at 3 h after challenge with 1 μg/ml LPS, whereas TLR1 and TLR2 mRNA were increased (p < 0.01) at 6 h after challenge with 10 μg/ml LPS. TLR4 increased (p < 0.001) at 3 h after challenge with LPS and remained constant. TLR5 and TLR6 mRNA increased (p < 0.05) at 9 h and 1 h after of LPS stimulation, respectively. The mRNA of CD14 and MD2 were increased (p < 0.001) at 1 h after LPS stimulation. Additionally, at most of the time analyzed, the mRNA expression increased with the dose of LPS. The LPS concentration had influence (p < 0.05) on all the TLRs expression except TLR10; whereas time had effect (p < 0.05) on all TLRs expression except TLR2, 3, 6 and 10. When compared to the control, the cytokines IL1b, IL8 and TNFα proteins were increased (p < 0.001) immediately at 1 h after LPS stimulation and remained constant till 48 h. IL12b was increased (p < 0.001) 12 h after challenge with 10 μg/ml of LPS. Although IL8 level was the highest, the higher (p < 0.05) expression of all these inflammatory cytokines indicate that upon interacting with TLRs, LPS exerted inflammatory response in PBMCs through the production of Th1 type cytokines. The production of cytokines was influenced (p < 0.001) by both the dose of LPS and the stimulation time. Hence, the porcine PBMCs are likely able to express all members of TLRs.

Keywords: TLRs, PBMCs, Cytokines, LPS, Innate immune response

1. Introduction

Toll-like receptors (TLRs) as pattern-recognition receptors (PRRs), recognize the microbial components (pathogen-associated molecular patterns; PAMPs), induce the inflammatory cytokines which in turn regulate and steer the subsequent immune response. Each TLR responds to specific ligands (PAMPs). Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) of the Gram-negative bacterial cell wall component are recognized by a receptor complex containing TLR4, CD14 and MD2 (Akira and Takeda, 2004), and promotes the production of the Th1-inducing cytokines IL12, IL1, IL6 and TNFα (Raymond and Wilkie, 2005; Re and Strominger, 2001). Notably, TLR expression patterns changes in relation to the pathogen involved (Akira and Takeda, 2004), expressed differentially among the immune cells and the maturation stage of cells (Hornung et al., 2002; Kokkinopoulos et al., 2005). Porcine TLR2 and TLR4 up-regulation is reported in epithelial cells (Burkey et al., 2009) and in monocytes and monocyte derived dendritic cells (Raymond and Wilkie, 2005) in response to LPS. Additionally, the cellular patterns of TLR expression vary between different species, so the results of TLR stimulation in one species may not be predictive of what will occur in another (Krieg, 2007; Rehli, 2002).

In swine, TLR1 through TLR10 have been characterized at the molecular level and several TLRs gene expression patterns have been characterized in different porcine tissues (reviewed by Uenishi and Shinkai, 2009). Differential TLRs expression is also reported in porcine cells in response to specific pathogens or TLR ligands (Alvarez et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2008; Zhu et al., 2008). Expression of TLR1–10 in human PBMCs (Hornung et al., 2002; Mendes et al., 2011; Siednienko and Miggin, 2009), and dendritic cells (Kokkinopoulos et al., 2005) and in selected tissues in goat (Tirumurugaan et al., 2010), sheep (Nalubamba et al., 2007), cattle (Menzies and Ingham, 2006), cat (Ignacio et al., 2005) and chicken (Iqbal et al., 2005) have been studied. Notably, there is a correlation between TLRs gene expression rate and LPS responsiveness (Jaekal et al., 2007). To our knowledge, no study was devoted to investigate TLR1–10 expression in porcine PBMCs stimulated by LPS. Treatment of porcine PBMCs with LPS resulted in expression or up-regulation of mRNAs for a variety of cytokines, including IL1, IL10, IL12, TNFα and IFNγ (Sorensen et al., 2011). Cytokines expression by the PBMCs is reported to be LPS dose- and time-depended in human (Muller-Alouf et al., 1994) and vary according to stimulation time and types of immune cells in human and swine (Chen et al., 2010; Yancy et al., 2001). Therefore, it is necessary to investigate the effect of different concentrations of TLR ligands for a course of time.PBMC comprising lymphocytes and monocytes/macrophages play pivotal roles in the immune response to invading pathogens. PBMCs express mRNAs encoding TLR1–10 and their crucial role in eliciting immune response make them a useful model in immune research (Gao et al., 2010; Siednienko and Miggin, 2009). In order to elucidate the role of PBMCs in regulation of porcine immune response, it is necessary to better understand the effects of PAMPs on porcine PBMCs that are involved in the recognition of pathogens. In response to specific ligand, a wide range of TLRs and cytokines is involved in porcine PBMCs but the relative abundance of TLR mRNA in the presence of bacterial LPS has not been fully characterized. Therefore, the objective of the current study was to investigate the relative abundance of all porcine TLRs and associated molecules (CD14 and MD2) gene transcripts in porcine PBMCs and its secretion of inflammatory cytokines (IL1β, IL8, IL12β and TNFα) protein in vitro in the presence of two different concentrations of LPS.

2. Material and methods

2.1. PBMCs isolation and culture

Blood was collected from three clinically healthy Pietrain (male and 2 months old) pigs. PBMCs were isolated from heparinized blood using the Ficoll-Histopaque (Sigma, Cat. 10831) following the manufacturer’s instructions. In brief, 15 ml of histopaque was added to 15 ml of heparinized blood in 50 ml falcon tube and centrifuged at 400 × g for 30 min at room temperature. The middle whitish interface (PBMCs) was collected and washed by adding 30 ml of D-PBS (Sigma–Aldrich) followed by centrifugation at 250 × g for 10 min three times. PBMCs were cultured in RPMI-1400 medium (Sigma–Aldrich) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, streptomycin and penicillin, 2-mercaptoetthanol and l-glutamine.The viability of PBMCs was tested using the trypan blue method. The concentration was adjusted to 2 × 106/ml and 1 ml of cell suspension was plated in each well in 24 well cell culture plate.The cells were cultured at 37 °C with 5% CO2. The cells were challenged with 1 μg/ml and 10 μg/ml of lipopolysaccharides (LPS from Escherichia coli 055:B5 – γ-irradiated, BioXtra; Cat. L6529, Sigma–Aldrich, Germany). For each stimulated well, there was an un-stimulated (control) well in the same cell culture plate. The cells were harvested at 1 h, 3 h, 6 h, 9 h, 12 h, 24 h and 48 h after stimulation. The cell culture supernatant was collected from each well and then cells were harvested after washing with D-PBS. To ensure complete harvesting of cells, wells were checked under microscope. The supernatants and harvested cells were kept in −80 °C till use.

2.2. RNA isolation and cDNA synthesis

Total RNA was isolated from the cells using the PicoPure (Cat. No. KIT024; Applied Biosystems, Arcturus) according to manufacture’s protocol. In brief, cells were extracted by adding 100 μl of extraction and 300 μl of lysis buffer followed by 30 min incubation at 42 ° C. Following centrifugation, the supernatant containing the extracted RNA was collected and 100 μl of 70% ethanol was added and was pipetted into a preconditioned purification column. The RNA was bound to the column and the column was then washed using wash buffer. The RNA eluted with 20 μl of elution buffer. In order to remove possible contaminations of genomic DNA, the extracted RNA was treated with 5 μl RQ1 DNase buffer, 5 μl of DNase, and 1 μl of RNase inhibitor in a 44 μl reaction volume (Invitrogen). The mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 1 h followed by purification using the Qiagen RNeasy Minikit (No. 74106; Qiagen) following manufacturer’s instructions. The quantity and quality of RNA was measured using Nanodrop 8000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific). The RNA integrity was checked by denaturing agarose gel electrophoresis and ethidium bromide staining. Purified RNA was stored at −80 °C for further cDNA synthesis. cDNA was synthesized from the isolated RNA using SuperScript®II (No. 18064-014; Invitrogen). In brief, 1 μl each of 100 μM Oligo dT and 1 μl of Random Primer was mixed with 1 μg of total RNA in 9 μl of DEPC water. The mixture was incubated at 68 °C for 5 min then chilled on ice for 2 min. A 20 μl mixture of 4 μl 5 × reaction buffer, 1 μl 0.1 M dTT, 1 μl 10 mM dNTP, 1 μl Superscript II reverse transcriptase, 1 μl RNasin and DEPC water was added to the RNA mixture in a PCR strip and run in a thermocycler programmed as 25 °C, 5 min; 42 °C, 60 min; 72 °C 15 min and hold at 4 °C. The synthesized cDNA was confirmed in a PCR reaction using GAPDH as primer and kept at −20 °C until use.

2.3. Quantitative real-time PCR

Primers for ten TLRs (1–10), CD14, MD2, B2M and SDHA were designed from FASTA product of the GenBank mRNA sequences for Sus scrofa TLRs using Primer3 program (Rozen and Skaletsky, 2000). Details of the primers are described in Table 1. Each of the primers was used in PCR reaction to amplify their corresponding gene and the products were confirmed using agarose gel electrophoresis. The PCR products were then purified using the QIAquick PCR purification kit (Cat. No. 28104; Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. For the standard curve in quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR), nine-fold serial dilutions of the plasmid were used. For this purposes, the purified PCR fragments were ligated into plasmid pGEM®-T vector (Promega) and the ligated products were inserted into competent JM109 (E. coli) following routinely used protocols. The competent cells were cultured and the best clones based on the M13 PCR results were further incubated in ampicillin added LB-broth medium in a shaking incubator at 37 °C overnight. Finally the plasmid DNA was isolated by using GenElute™ Plasmid Miniprep Kit (Sigma–Aldrich) as described by the manufacturer. Plasmid size and quality was determined in agarose gel electrophoresis. An aliquot of plasmid DNA was sequenced (Beckman Coulter) for the product confirmation and the rest was stored at −20 °C to be used as template for setting up the standard curve in qPCR.

Table 1.

List of primers and qRT-PCR efficiencies.

| Gene name | GenBank accession Nr. | Forward/reverse | Amplicon length | Amplification efficiency | R 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TLR1 | NM_001031775.1 | ATGTGTGCTGGATGCTAACGAGACAAACTGGAGGGTGGTG | 140 | 97.04% | 0.991 |

| TLR2 | NM_213761.1 | CAGTCCGGAGGTTGCATATTATGCTGTGAAAGGGAACAGG | 137 | 110.33% | 0.988 |

| TLR3 | NM_001097444.1 | CTTGACCTCGGCCTTAATGACAAGGCGAAAGAGTCGGTAG | 129 | 111.04% | 0.986 |

| TLR4 | NM_001113039.1 | TGGAACAGGTATCCCAGAGGCAGAATCCTGAGGGAGTGGA | 125 | 110.95% | 0.992 |

| TLR5 | NM_001123202.1 | GTTCTCGCCCACCACATTATTCGGAAGTTCAGGGAGAAGA | 144 | 108.05% | 0.988 |

| TLR6 | NM_213760.1 | TTCACCTGGTCTTTCATCCAGCCCTTGAGTGAGTTCCAAT | 150 | 111.09% | 0.992 |

| TLR7 | NM_001097434.1 | TTGTTCCATGTATGGGCAGAGGCTGAAATTCACTGCCATT | 150 | 104.66% | 0.997 |

| TLR8 | NM_214187.1 | TCTGTCTTCAAATGGCAACGGAAAGCAGCGTCATCATCAA | 118 | 111.14% | 0.991 |

| TLR9 | NM_213958.1 | TGGCCATTACTAGGGAGGTGGTCCAAGGTGAAGCTGAAGG | 134 | 97.35% | 0.988 |

| TLR10 | NM_001030534.1 | CTTCCTGGGTGCAGTCATTTCACAAGTACACCGGAATGGA | 145 | 102.17% | 0.987 |

| CD14 | NM_001097445.2 | TGCCAAATAGACGACGAAGAACGACACATTACGGAGTCTGA | 174 | 102.09 | 0.999 |

| MD2 | NM_001104956.1 | TGCAATTCCTCTGATGCAAGCCACCATATTCTCGGCAAAT | 226 | 93.66 | 0.987 |

| SDHA | DQ178128.1 | AGAGCCTCAAGTTCGGGAAGCAGGAGATCCAAGGCAAAAT | 141 | 91.13% | 0.998 |

| B2M | NM_213978.1 | ACTTTTCACACCGCTCCAGTCGGATGGAACCCAGATACAT | 180 | 91.89% | 0.997 |

R2: correlation coefficient of the slope of the standard curve.

To quantify the mRNA expression for TLRs, CD14, MD2 and reference genes (B2M and SDHA), qPCR was performed using the ABI Prism® 7000 quantitative real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystem). Since nine-fold serial dilution of plasmids DNA were used as template for the generation of the standard curve, in each run, the 96-well microtitre plate contained each cDNA sample, plasmid standards and no-template control. qPCR was set up using 2 μl of first-strand cDNA template, 7.6 μl of deionized H2O, 0.2 μM of upstream and downstream primers, and 10 μl of 1 × Power SYBR Green I master mix with ROX as reference dye (Bio-Rad). The thermal cycling conditions were 3 min at 95 °C followed by 15 s at 95 °C and 1 min at 60 °C (40 cycles). An amplification-based threshold and adaptive baseline were selected as algorithms. The concentration of the unknown cDNA was calculated according to the standard curve. The PCR amplification efficiency of each primer pair was calculated from the slope of a standard curve. Melting curve analysis was constructed to verify the presence of gene-specific peak and the absence of primer dimer. Agarose gel electrophoresis was performed to test for the specificity of the amplicons. The expression level of transcript (TLRs, CD14, MD2) was normalized relatively to the average transcript of porcine reference genes B2M and SDHA (Table 1), where the expression (copy number) of target gene was divided by the geometric mean of the expression (copy number) of two reference genes (B2M and SDHA). Final results were reported as the relative expression level after normalized using the reference genes. Each sample was run twice and the average value was used as expression values.

2.4. Cytokines measurement using ELISA

The protein level of cytokines (IL1β, IL8, IL12β and TNFα) were measured from PBMCs culture supernatant using commercially available porcine ELISA Kits such as Quantikine® porcine IL-12/IL-23 p40 immunoassay (Cat. P1240), Quantikine® porcine IL-8/CXCL8 immunoassay (Cat. P8000), Quantikine® porcine IL-1β/IL-1F2 immunoassay (Cat. PLB00B) and Quantikine® porcine TNF-α immunoassay (Cat. PTA00) (R&D System) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The OD value was detected at 450 nm wave-length using ELISA plate reader (Molecular Devices GmBH) and the concentrations were determined (pg/ml) according to the standard using microplate data compliance software SoftMax Pro (Molecular Devices GmBH). To ensure the repeatability of the experiment, each sample was measured twice and the average concentration was used as protein level (pg/ml) in cell culture supernatant.

2.5. Data analysis

The data were analyzed using the SAS software package ver9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Generalized linear models (Proc GLM) were used to determine any possible effect of stimulation time and concentration of LPS on TLRs expressions. Differences in TLRs gene expressions were analyzed using Tukey-test in SAS. Values of p < 0.05 were considered to indicate statistically significant differences.

3. Results

3.1. TLRs and associated genes expression in PBMCs is altered in response to LPS stimulation

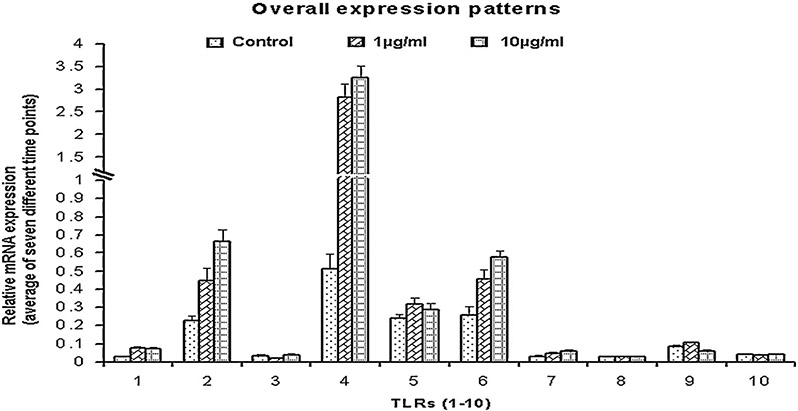

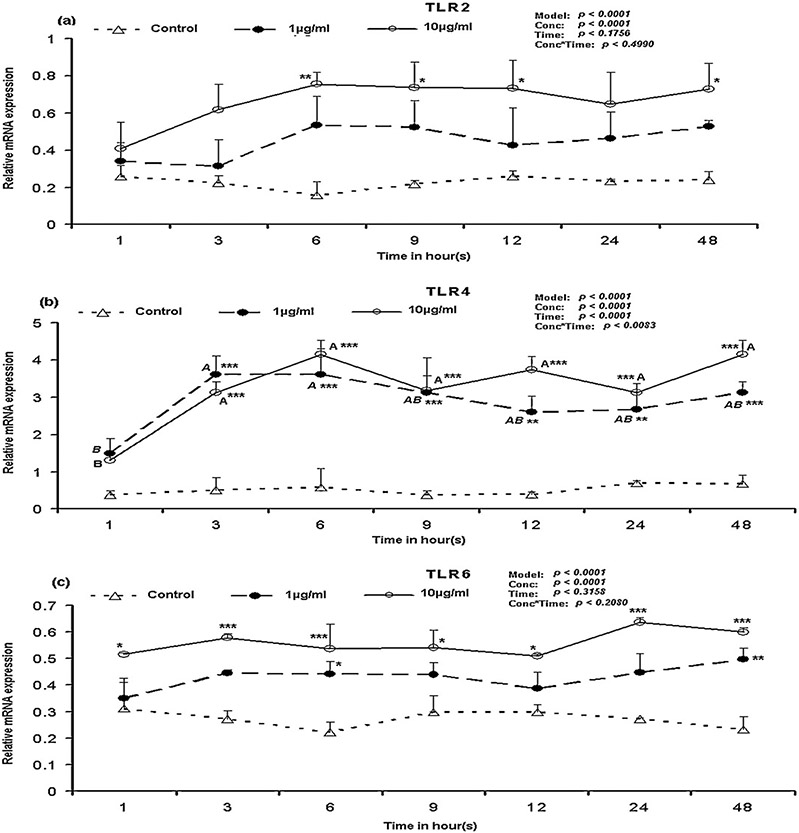

The transcripts of all ten TLRs were detectable in porcine PBMCs stimulated with LPS. Among them, TLR4 was the highest expressed gene followed by TLR2 and TLR6 (Fig. 1). Compared to TLR4, the mRNA expression of TLR1, 3, 7, 8 and 10 were low. When compared to the control (un-stimulated), TLR1 mRNA was increased significantly (p < 0.05) at 3 h, 6 h and 24 h (p < 0.01) and 48 h (p < 0.001) after 1 μg/ml LPS stimulation (Supplementary Fig. S1a). When stimulated with 10 μg/ml LPS, in comparison to the control, TLR1 mRNA was increased significantly at 6 h after stimulation and remained significantly (p < 0.05) higher till 48 h. Notably, when the TRL1 mRNA expression between the time points in response to 1 μg/ml LPS were compared, TLR1 mRNA expression was significantly higher at 3 h, 6 h, 24 and 48 h compared to the its expression at 1 h (Supplementary Fig. S1a). TLR2 showed higher expression only in response to the 10 μg/ml at 6–12 h and 48 h (Fig. 2a). Though statistical analysis showed (Proc GLM) that TLR3 mRNA expression was influenced by LPS concentration (p < 0.0001), the gene expression was non-significant when compared to the control (data not shown). TLR4 gene expression was significantly (p < 0.001) higher at 3 h following the stimulation with LPS and remained constantly higher till 48 h when compared to the control (Fig. 2b). When the TLR4 mRNA expression between time points for 1 μg/ml LPS were compared, the mRNA expression was significantly (p < 0.05) higher at 3 h and 6 h in comparison to its expression at 1 h (Fig. 2b). But in case of the 10 μg/ml, TLR4 mRNA expression was increased (p < 0.05) at 3–48 h after LPS stimulation in comparison to its level at 1 h (Fig. 2b). TLR5 mRNA expression was increased significantly (p < 0.05) only at 9 h after stimulation with LPS (Supplementary Fig. S1b). Notably, the TLR5 mRNA expression in control at 12 h and 24 h was higher than the expression in LPS stimulated cells and the expression level in control cells at 24 h was significantly (p < 0.05) increased in comparison to its level at 3–9 h (Supplementary Fig. S1b). In comparison to the control, TLR6 mRNA expression was significantly (p < 0.05) increased immediately at 1 h after the LPS stimulation and remained constantly higher till 48 h in case of the 10 μg/ml LPS (Fig. 2c).

Fig. 1.

Overall TLR1–10 mRNA expression patterns in LPS stimulated PBMCs. Data are expressed as the mean of all seven time points for a TLR within the same concentration of LPS.

Fig. 2.

TLR2, TLR4 and TLR6 mRNA expression in LPS stimulated PBMCs over time. Bar without common superscripts (lower case letter for control; capital-italic letter for 1 μg/ml LPS; and capital [non-italic] letter for 10 μg/ml LPS) differ (p < 0.05). Data are expressed as mean ± SD of duplicate samples; error bars for some conditions were so small they are obscured be the symbols. Relative mRNA expression of TLRs: (a) TLR2; (b) TLR4 and (c) TLR6. When LPS-stimulated mRNA expression values within a time point are compared with control: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. Proc GLM data for each gene are shown on top-left corner.

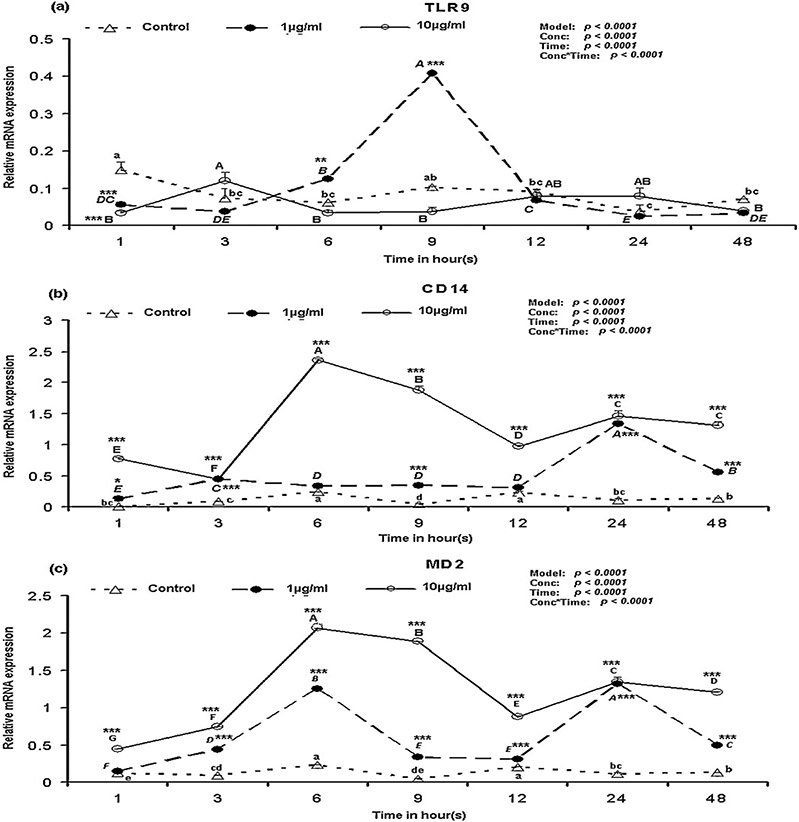

The mRNA expression of TLR7, in response to the LPS was non-significant when compared to the control (data not shown). TLR8 mRNA expression remained at the same in LPS stimulated PBMCs over time (Supplementary Fig. S1c). It is worth to mention that at 1 h after stimulation with LPS, the TLR9 mRNA expression in control was higher compared to its expression in LPS stimulated PBMCs (Fig. 3a). However, this mRNA expression at 1 h in control was decreased significantly (p < 0.05) at 3 h (Fig. 3a) and remained in the similar level with 10 μg/ml LPS. When compared to the control, at 1 h after LPS stimulation, the TLR9 mRNA expression was significantly (p < 0.001) lower and increased significantly (p < 0.01) at 6 h and 9 h after stimulation with 1 μg/ml LPS (Fig. 3a). Notably, when the TLR9 mRNA expression in response to the two different concentrations of LPS were compared, the TLR9 expression was significantly (p < 0.001) higher at 3 h with 10 μg/ml LPS (Supplementary Fig. S2a) but was significantly higher (p < 0.001) at 6 h and 9 h with 1 μg/ml LPS (Supplementary Fig. S2a). No differential TLR10 mRNA expression was detected in response to LPS stimulation in porcine PBMCs in this study (data not shown). TLR1, 4, 5, 7, 8 and 9 mRNA expressions were influenced by both the time of stimulation and the concentration of LPS used in this study, while TLR2, 3 and 6 mRNA expressions were influenced only by the concentration of LPS (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. S1).

Fig. 3.

TLR9, CD14 and MD2 mRNA expression in LPS stimulated PBMCs over time. Bar without common superscripts (lower case letter for control; capital-italic letter for 1 μg/ml LPS; and capital [non-italic] letter for 10 μg/ml LPS) differ (p < 0.05). Data are expressed as mean ± SD of duplicate samples; error bars for some conditions were so small they are obscured by the symbols. Relative mRNA expression of TLRs and associated molecules: (a) TLR9; (b) CD14 and (c) MD2. When LPS-stimulated mRNA expression values within a time point are compared with control: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. Proc GLM data for each gene are shown on top-left corner.

Beside the expression of TLR1–10 mRNA, this study was also devoted to quantify the CD14 and MD2 mRNA expression in response to the different concentrations of LPS over time. When compared to the control, in response to 1 μg/ml LPS the CD14 mRNA expression was significantly (p < 0.05) higher over the time points (except 6 h and 12 h) but were significantly higher at all the time points in response to the 10 μg/ml LPS (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Fig. S2b). Except at 1 h after the stimulation with 1 μg/ml LPS, the MD2 mRNA expression was significantly (p < 0.001) higher than the control at all the time points in response to LPS (Fig. 3c). Notably, the MD2 mRNA expression was significantly higher (p < 0.001) in response to 10 μg/ml LPS at most of the time points (except at 24 h) when compared to 1 μg/ml LPS (Supplementary Fig. S2c). In most of the time points, the CD14 and MD2 mRNA expression was significantly (p < 0.001) higher in response to the higher dose of LPS in this study (Supplementary Fig. S2b and c).

3.2. Kinetics of cytokines expression in LPS-induced PBMCs culture supernatant

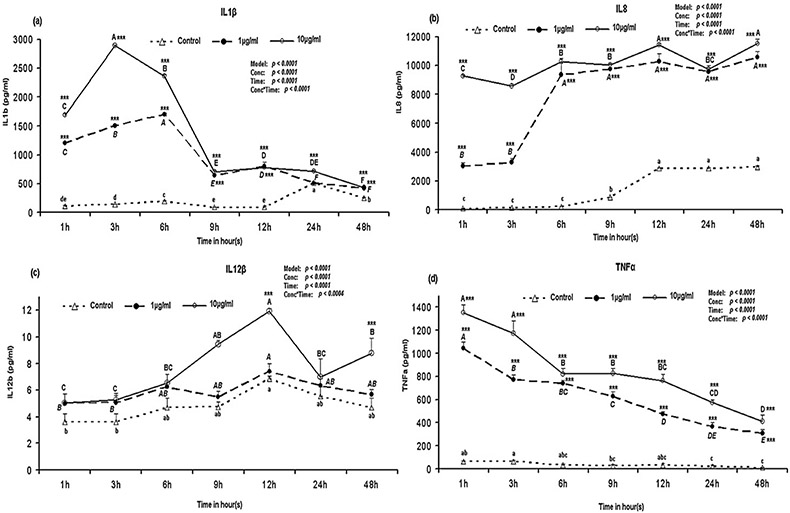

Among the cytokines measured in this study, IL8 was detected at the highest level in all the time points (Fig. 4b). The protein level of IL1β was increased (p < 0.001) immediately at 1 h after the stimulation with both concentrations of LPS and started to decrease after 9 h of stimulation but still remained significantly (p < 0.001) higher when compared to the control (Fig. 4a) except at 24 h stimulation with 1 μg/ml LPS. IL1β production was significantly higher with the higher dose of LPS at 1 h to 6 h after stimulation (Supplementary Fig. S3a). The IL8 was increased (p < 0.001) immediately at 1 h after the LPS stimulation and remained significantly (p < 0.001) higher in all of the time points when compared with the control (Fig. 4b). Notably, the IL8 protein production was significantly higher with the higher dose of LPS at 1–3 h after stimulation of the porcine PBMCs (Supplementary Fig. S3b). The IL12β showed delayed response in comparison to other cytokines since the IL12β was increased significantly (p < 0.001) at 12 h after the stimulation with 10 μg/ml of LPS (Fig. 4c) when compared to the control. Moreover, the IL12β protein levels were significantly (p < 0.01) higher at 9 h, 12 h and 48 h in PBMCs culture supernatant stimulated with the higher dose of LPS when compared to the lower dose of LPS (Supplementary Fig. S3c). While other cytokines levels were variable with times, TNFα was decreased gradually with the advancement of time (Fig. 4d). The TNFα protein reached the highest level (p < 0.001) at 1 h after LPS stimulation (Fig. 4d) and decreased with the time, but remained significantly (p < 0.001) higher till 48 h after the stimulation. The TNFα protein production with the higher dose of LPS was always higher than the lower dose of LPS (Fig. 4d). In response to the 10 μg/ml LPS, the TNFα protein levels in the culture supernatant were significantly (p < 0.05) higher than 1 μg/ml LPS at 1 h, 3 h, 9 h, 12 h and 24 h after stimulation (Supplementary Fig. S3d).

Fig. 4.

Cytokines protein production by LPS stimulated PBMCs over time. Bar without common superscripts (lower case letter for control; capital-italic letter for 1 μg/ml LPS; and capital [non-italic] letter for 10 μg/ml LPS) differ (p < 0.05). Data are expressed as mean ± SD of duplicate samples; error bars for some conditions were so small they are obscured by the symbols. Cytokines protein (pg/ml) measured in the PBMCs culture supernatant: (a) IL1β; (b) IL8; (c) IL12 and (d) TNFα. When LPS-stimulated cytokines protein production values within a time point are compared with control: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. Proc GLM data for each gene are shown on top-left corner.

4. Discussion

TLRs play important roles in the innate immune response against bacteria, viruses, fungi and parasites in early stages of infection by recognizing the invading organisms as well as to induce the adaptive immune response for long term defense. Although pig is described as the most appropriate model animal for understanding human innate immunity and disease in regards to the mononuclear cells (Fairbairn et al., 2011), TLRs expression studies in porcine PBMCs in response to bacterial product are rare. This study found that in porcine PBMCs, LPS stimulation, representative of Gram-negative bacterial infections, resulted in the modulation of most of the TLRs genes expression over time (Figs. 2 and 3 and Supplementary Fig. S2). Consistent with this result, TLRs gene expression difference has been reported in unstimulated PBMCs (Siednienko and Miggin, 2009), in bacterial CpG stimulated PBMCs (Hornung et al., 2002), and in LPS stimulated dendritic cells (Kokkinopoulos et al., 2005) in human. The modulation of TLR2, 3, 4, 7, 8 and 9 gene expressions in porcine tissues and PBMCs has been observed with LPS stimulation (Liu et al., 2009). The TLRs expression is reported to vary according to the duration of stimulation- (Gomes et al., 2010) and dose-of LPS (Hirschfeld et al., 2000). The higher expression of TLRs is reported in cells with higher dose of LPS (Hirschfeld et al., 2000) which is in agreement with our findings in most of the cases. LPS is reported to stimulate CD14 expression in vitro in porcine alveolar macrophages (AMs) (Kielian et al., 1995) and CD14 is expressed in dose-dependent manner in LPS stimulated human PBMCs (Youn et al., 2008). TLR4 increased at 3 h and 6 h after stimulation with low and high dose of LPS, respectively and maintained the same level (Fig. 2b). In human, TLR4 is reported to increase on monocytes at 6 h after stimulation with LPS in vivo (Gomes et al., 2010). Our data showed that TLR4, TLR1 and TLR2 are up-regulated in porcine PBMCs upon LPS challenge (Fig. 2a and b and Supplementary Fig. S1a). Gram-positive bacteria and yeast cell wall components are ligands for TLR1, TLR2 and TLR6, whereas the predominant Gram-negative bacterial product LPS is a ligand for TLR4 (Akira and Takeda, 2004). Although, TLR2 is reported to be induced by LPS stimulation and its expression is reported to be low in individuals who are low responsive for LPS (Jaekal et al., 2007). Moreover, numerous reports have indicated that LPS is not a ligand for TLR2, the TLR2-stimulating activity of commercial LPS being due to the presence of contamination with other microbial components triggering TLR2 signaling (Hirschfeld et al., 2000). The expression of TLR1 and TLR2 might explain that TLR1 heterodimerizes with TLR2 in response to LPS (Pulendran et al., 2001). TLR2 and TLR4 expression is reported to remain unchanged in human monocyte in response to LPS (Kokkinopoulos et al., 2005). Gao et al. (2010) did not find over expression of either TLR2 or TLR4 in LPS stimulated porcine PBMCs. Notably, PBMCs consist of both the adherent (monocytes) and non-adherent (lymphocytes) immune cells (Blomkalns et al., 2011). The LPS responsiveness of individual PBMCs is reported to be contributed by the constitutive expression levels of TLR2 and TLR4 in human (Jaekal et al., 2007). Undoubtedly, both TLR2 and TLR4 are important in the inflammatory response to Gram-negative bacterial infection because both endotoxins bacterial lipoprotein and LPS are present in the context of whole bacteria (Hirschfeld et al., 2000).In the present study an increased expression of TLR6 (Fig. 2c) was observed suggesting a particular role of this receptor gene in PBMCs. TLR6 is reported to be down regulated in porcine PBMCs after stimulation with LPS (Gao et al., 2010). TLR6 is expressed in human monocytes (Hornung et al., 2002) and forms a heterodimeric structure with TLR2 (Farhat et al., 2008). Heterodimerization of TLR2 with TLR1 or TLR6 is evolutionarily developed to expand the ligand spectrum to enable the innate immune system to recognize the numerous, different structures of lipopeptides present in various pathogens such as mycoplasma, Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria (Farhat et al., 2008). The TLR3, 7 and 8, are involved in recognizing viral particles like dsRNA or mimics of it (Kokkinopoulos et al., 2005). Human TLR3 transcripts were detectable in PBMCs upon LPS challenge (Hornung et al., 2002; Siednienko and Miggin, 2009) which is in agreement with our finding that TLR3 gene expression remained unchanged in response to LPS. In this study, TLR7 was detectable, but did not increase significantly compared to the unstimulated control. Human TLR7 was absent in all leukocyte populations prior and after LPS stimulation (Kokkinopoulos et al., 2005) but was detected in human PBMCs in response to CpG ODN (Hornung et al., 2002). TLR8 is a viral receptor and reported to express lower in LPS stimulated human monocyte and dendritic cells compared to non-LPS stimulated cells (Kokkinopoulos et al., 2005). Recently, TLR8 is reported to be down regulated in porcine PBMCs after stimulation with LPS (Gao et al., 2010). In this study, TLR8 remained unchanged after stimulation with LPS (Supplementary Fig. S1c). This study detected very low expression of TLR3, 7, 8 and 10 compared to other TLRs upon LPS challenge (Fig. 1), which implies that the TLRs related to bacterial infections were activated by LPS. More importantly, virus infections have been shown to sensitize the host for bacterial products such as LPS (Nansen and Randrup Thomsen, 2001). This study revealed the overall expression of TLR5 and TLR9 (Supplementary Figs. S1b and S3a) which recognize flagellin structures and CpG islands, respectively (Akira and Takeda, 2004). It is noticeable that the alteration of TLR5 was decreased after 12 h while it was increased in control (Supplementary Fig. S1b). TLR9 expression was higher in control than the LPS-stimulated PBMCs at 1 h after the stimulation and increased at 9 h only in response to the lower concentration of LPS (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. S2a). These findings are interesting since it characterizes a high complexity in the specificity of recognition toward TLR9 and TLR5. Similar complex alteration of TLR5 and TLR9 has been reported in LPS stimulated human monocytes and dendritic cells (Kokkinopoulos et al., 2005). It is difficult to explain these differences but E. coli species contain variants possessing flagellum (Akira and Takeda, 2004) and CpG unmethylated regions within their nuclear DNA (Kokkinopoulos et al., 2005).

CD14 (cluster of differentiation antigen 14) is crucial for LPS recognition by TLR4 and, in addition, cooperates with other TLRs, including TLR2 and TLR3 (Akashi-Takamura and Miyake, 2008). While the expression of the CD14 on LPS stimulated human monocytes and neutrophils has been documented (Gomes et al., 2010), the expression studies of CD14 in porcine PBMCs are rare. Recently, using microarray analysis, CD14 is reported to be up-regulated in porcine PBMCs after stimulation with LPS (Gao et al., 2010). Rapid increase of CD14 at 3 h after LPS and E. coli challenge is reported in porcine granulocytes (Thorgersen et al., 2010). Elevated CD14 expression in response to LPS is reported in porcine AMs (Kielian et al., 1995). Moreover, higher CD14 expression is reported at 24 h after stimulation with both low and high concentrations of LPS (Kielian et al., 1995) which is in good agreement with our findings (Fig. 3b). This study found that CD14 expression in LPS stimulated PBMCs was higher in response to the higher concentration of LPS (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Fig. S2b). Therefore, along with the previous results (Kielian et al., 1995), these data suggest that the degree of CD14 up-regulation is related to LPS concentration. MD2 (myeloid differentiation 2) is physically associated with TLR4 on the cell surface and confers responsiveness to LPS and MD2 is thus a link between TLR4 and LPS signaling (Akira and Takeda, 2004). Highest expression of TLR4 and MD2 has been reported in porcine AMs in response to LPS (Ren et al., 2010; Islam et al., 2012). This study identified higher expression of MD2 mRNA in LPS stimulated porcine PBMCs (Fig. 3c) that was induced higher by the higher concentration of LPS (Supplementary Fig. S2c). However, no study was devoted to investigate the expression of MD2 in porcine blood cells.

It is difficult to compare directly the results form different studies, because qPCR results are normalized in different ways. Recently we have shown that the reference genes used in this study, SDHA and B2M are stably expressed in varieties of porcine tissues including PBMCs (Uddin et al., 2011). While TLRs expression studies in PBMCs are being compared with the expression in other cell type (such as dendritic cells) or in PBMCs subsets (like monocytes, T-cells and B-cells) that lead to differences (Hornung et al., 2002; Kokkinopoulos et al., 2005). The expression of all TLRs including TLR2 and TLR4 could be due to the purity of LPS (Hirschfeld et al., 2000), species (Nalubamba et al., 2007) and because of the TLRs since they work cooperatively through complex pathways (Akira and Takeda, 2004). It could be seen that the PCR amplification varies between 91.13% and 111.14% in this experiment (Table 1). Therefore, it is worth to mention that the big span of the qPCR amplification efficiency (Table 1) may have effect on the mRNA expression (detailed reviewed by Bustin et al., 2009) which might be due to the different amplicon size, different run, residual RNA in DNA preparation, different samples etc. (Meijerink et al., 2001).

The measurement of cytokine production is the easiest assessment for cell responsiveness, which is used for different in vitro models (Jaekal et al., 2007). Stimulation of TLR results in the activation of nuclear factor-kB (NF-kB) and up-regulation of costimulatory molecules and proinflammatory cytokines. LPS induce various cytokine productions in mouse macrophage cells mainly through the NF-kB signaling pathway (Jaekal et al., 2007) and LPS-induced cytokine release is TLR4-dependent (Mukherjee et al., 2009). LPS induces IFNγ, TNFα and IL8 through MyD88-dependent TLR signaling pathway (Mukherjee et al., 2009). Gao et al. (2010) showed that LPS stimulation induced a general inflammation response with over-expression of IL1 β, IL1α, TNFα and IL8 in porcine PBMCs. Additionally by using ELISA, Gao et al. (2010) confirmed the over expression of IL1β, IL8, IL12 and TNFα protein in LPS stimulated porcine PBMCs culture supernatant. Up-regulation of IL8 has already been reported in pig PBMCs (Lin et al., 1994). IL1 has been reported to activate chemokine production and IL1 was not only up-regulated in LPS stimulated porcine PBMCs but also it occupies a central position in the LPS-related network providing a global image of inflammation activation (Gao et al., 2010). This study identified that cytokine production by porcine PBMCs are different between the concentration of LPS (Supplementary Fig. S3) which is coinciding with other results in human and mice (Blomkalns et al., 2011; Chen et al., 2010). Our data are in good agreement with the findings of Sorensen et al. (2011) who recently reported that the IL1β and IL12 protein expressions was varying with time in LPS stimulated porcine PBMCs. The cytokine expressions in this study indicate the LPS responsiveness of the PBMCs and the higher expression of IL1, IL8, IL12 and TNFα (Fig. 4a-d) indicates Th1-associated inflammatory response of porcine PBMCs in response to LPS. PAMP binding to TLR4 is reported to promote the production of Th1-inducing cytokines IL12, IL1, IL6 and TNFα in human (Re and Strominger, 2001). TLR4 is also reported to be necessary for optimum development of Th2 response and LPS is triggering the production of Th2 type cytokines in mouse macrophages (Mukherjee et al., 2009). Our study identified higher expression of IL12 (Fig. 4c) which is known to be required for the development of Th1 immune response. Curiously, however, in the present study the TNFα protein production of LPS stimulated PBMCs was reduced with time (Fig. 4d). Sorensen et al. (2011) documented, that while cytokines IFNγ, IL12, IL1β, IL6 and IL10 are varying with time, TNFα remained at the same level with control in LPS stimulated porcine PBMCs. CpG DNA stimulated porcine PBMCs induced TLR9 mRNA expression and an increased production of IL1, IL6, IL12 and IFNα protein, but decreased production of TNFα protein (Dar et al., 2008) which is in good agreement with our results. In addition to triggering inflammatory response, the TLRs also leads to the activation of inhibitory feedback mechanisms that ultimately attenuate the response (Gao et al., 2010). In this study, IL8 protein production by LPS stimulated porcine PBMCs was always higher than the control (Fig. 4b). LPS-induced IL8 release by human total PBMCs and monocytes is changed over the range of LPS concentrations (Blomkalns et al., 2011). It is well known that IL8 is a potent chemoattractant and activator for neutrophils, lymphocytes and basophils. Recently, it has been reported that IL8 release is dependent on both CD14 and TLR4 in human PBMCs (Blomkalns et al., 2011).

Notably, the expression of proinflammatory cytokines is reported to be affected by the dose of LPS (Blomkalns et al., 2011; Chen et al., 2010; Sorensen et al., 2011) and depended on the time of stimulation (Blomkalns et al., 2011; Sorensen et al., 2011) in swine, human and mice. IL1β, IL12 and TNFα production was higher in porcine PBMCs upon LPS challenge in this study (Fig. 4a, c and d). Human PBMCs, stimulated with E. coli LPS, are reported to secrete significantly higher IL1β and TNFα proteins, but IL12 remained the same (Jansky et al., 2003). Similarly, differences in TNFα mRNA expression between LPS stimulated fresh blood, fresh and frozen PBMCs has been reported in human (Chen et al., 2010). The discrepancies between the studies could be due to the LPS, because LPS from E. coli was used in this study, whereas Sorensen et al. (2011) was used Salmonella typhimurum LPS. Moreover, cytokine work through complex ‘MyD88-dependent’ as well as ‘MyD88-independent’ TLR signaling pathways (Akira and Takeda, 2004) and are characterized by redundancy and pleiotropism. All these results confirm the essential role of chemokines in chemoattraction and cell guidance to the site of infection during bacterial infection.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetimm.2012.04.020.

References

- Akashi-Takamura S, Miyake K, 2008. TLR accessory molecules. Curr. Opin. Immunol 20, 420–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akira S, Takeda K, 2004. Toll-like receptor signalling. Nat. Rev. Immunol 4, 499–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez B, Revilla C, Domenech N, Perez C, Martinez P, Alonso F, Ezquerra A, Domiguez J, 2008. Expression of toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) in porcine leukocyte subsets and tissues. Vet. Res 39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blomkalns AL, Stoll LL, Shaheen W, Romig-Martin SA, Dickson EW, Weintraub NL, Denning GM, 2011. Low level bacterial endotoxin activates two distinct signaling pathways in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. J. Inflamm. (Lond) 8, 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkey TE, Skjolaas KA, Dritz SS, Minton JE, 2009. Expression of porcine Toll-like receptor 2, 4 and 9 gene transcripts in the presence of lipopolysaccharide and Salmonella enterica serovars Typhimurium and Choleraesuis. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol 130, 96–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bustin SA, Benes V, Garson JA, Hellemans J, Huggett J, Kubista M, Mueller R, Nolan T, Pfaffl MW, Shipley GL, Vandesompele J, Wittwer CT, 2009. The MIQE Guidelines: minimum information for publication of quantitative real-time PCR experiments. Clin. Chem 55, 4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Bruns AH, Donnelly HK, Wunderink RG, 2010. Comparative in vitro stimulation with lipopolysaccharide to study TNFalpha gene expression in fresh whole blood, fresh and frozen peripheral blood mononuclear cells. J. Immunol. Methods 357, 33–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dar A, Nichani AK, Benjamin P, Lai K, Soita H, Krieg AM, Potter A, Babiuk LA, Mutwiri GK, 2008. Attenuated cytokine responses in porcine lymph node cells stimulated with CpG DNA are associated with low frequency of IFNalpha-producing cells and TLR9 mRNA expression. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol 123, 324–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairbairn L, Kapetanovic R, Sester DP, Hume DA, 2011. The mononuclear phagocyte system of the pig as a model for understanding human innate immunity and disease. J. Leukoc. Biol 89, 855–871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farhat K, Riekenberg S, Heine H, Debarry J, Lang R, Mages J, Buwitt-Beckmann U, Roschmann K, Jung G, Wiesmuller KH, Ulmer AJ, 2008. Heterodimerization of TLR2 with TLR1 or TLR6 expands the ligand spectrum but does not lead to differential signaling. J. Leukoc. Biol 83, 692–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y, Flori L, Lecardonnel J, Esquerre D, Hu ZL, Teillaud A, Lemonnier G, Lefevre F, Oswald IP, Rogel-Gaillard C, 2010. Transcriptome analysis of porcine PBMCs after in vitro stimulation by LPS or PMA/ionomycin using an expression array targeting the pig immune response. BMC Genomics 11, 292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes NE, Brunialti MK, Mendes ME, Freudenberg M, Galanos C, Salomao R, 2010. Lipopolysaccharide-induced expression of cell surface receptors and cell activation of neutrophils and monocytes in whole human blood. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res 43, 853–858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschfeld M, Ma Y, Weis JH, Vogel SN, Weis JJ, 2000. Cutting edge: repurification of lipopolysaccharide eliminates signaling through both human and murine toll-like receptor 2. J. Immunol 165, 618–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornung V, Rothenfusser S, Britsch S, Krug A, Jahrsdorfer B, Giese T, Endres S, Hartmann G, 2002. Quantitative expression of toll-like receptor 1–10 mRNA in cellular subsets of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells and sensitivity to CpG oligodeoxynucleotides. J. Immunol 168, 4531–4537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ignacio G, Nordone S, Howard KE, Dean GA, 2005. Toll-like receptor expression in feline lymphoid tissues. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol 106, 229–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal M, Philbin VJ, Smith AL, 2005. Expression patterns of chicken Toll-like receptor mRNA in tissues, immune cell subsets and cell lines. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol 104, 117–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islam MA, Cinar MU, Uddin MJ, Tholen E, Tesfaye D, Looft C, Schellander K, 2012. Expression of Toll-like receptors and downstream genes in lipopolysaccharide induced porcine alveolar macrophages. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol, 10.1016/j.vetimm.2012.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaekal J, Abraham E, Azam T, Netea MG, Dinarello CA, Lim JS, Yang Y, Yoon DY, Kim SH, 2007. Individual LPS responsiveness depends on the variation of toll-like receptor (TLR) expression level. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol 17, 1862–1867. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansky L, Reymanova P, Kopecky J, 2003. Dynamics of cytokine production in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells stimulated by LPS or infected by Borrelia. Physiol. Res 52, 593–598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kielian TL, Ross CR, McVey DS, Chapes SK, Blecha F, 1995. Lipopolysaccharide modulation of a CD14-like molecule on porcine alveolar macrophages. J. Leukoc. Biol 57, 581–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokkinopoulos I, Jordan WJ, Ritter MA, 2005. Toll-like receptor mRNA expression patterns in human dendritic cells and monocytes. Mol. Immunol 42, 957–968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieg AM, 2007. Antiinfective applications of toll-like receptor 9 agonists. Proc. Am. Thorac. Soc 4, 289–294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin G, Pearson AE, Scamurra RW, Zhou Y, Baarsch MJ, Weiss DJ, Murtaugh MP, 1994. Regulation of interleukin-8 expression in porcine alveolar macrophages by bacterial lipopolysaccharide. J. Biol. Chem 269, 77–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu CH, Chaung HC, Chang HL, Peng YT, Chung WB, 2009. Expression of Toll-like receptor mRNA and cytokines in pigs infected with porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. Vet. Microbiol 136, 266–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meijerink J, Mandigers C, van de Locht L, Tönnissen E, Goodsaid F, Raemaekers A, 2001. A novel method to compensate for different amplification efficiencies between patient DNA samples in quantitative real-time PCR. J. Mol. Diagn 3 (2), 55–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendes ME, Baggio-Zappia GL, Brunialti MK, Fernandes Mda L, Rapozo MM, Salomao R, 2011. Differential expression of toll-like receptor signaling cascades in LPS-tolerant human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Immunobiology 216, 285–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menzies M, Ingham A, 2006. Identification and expression of Toll-like receptors 1–10 in selected bovine and ovine tissues. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol 109, 23–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee S, Chen LY, Papadimos TJ, Huang S, Zuraw BL, Pan ZK, 2009. Lipopolysaccharide-driven Th2 cytokine production in macrophages is regulated by both MyD88 and TRAM. J. Biol. Chem 284, 29391–29398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller-Alouf H, Alouf JE, Gerlach D, Ozegowski JH, Fitting C, Cavaillon JM, 1994. Comparative study of cytokine release by human peripheral blood mononuclear cells stimulated with Streptococcus pyogenes superantigenic erythrogenic toxins, heat-killed streptococci, and lipopolysaccharide. Infect. Immun 62, 4915–4921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nalubamba KS, Gossner AG, Dalziel RG, Hopkins J, 2007. Differential expression of pattern recognition receptors in sheep tissues and leukocyte subsets. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol 118, 252–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nansen A, Randrup Thomsen A, 2001. Viral infection causes rapid sensitization to lipopolysaccharide: central role of IFN-alpha beta. J. Immunol 166, 982–988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulendran B, Kumar P, Cutler CW, Mohamadzadeh M, Van Dyke T, Banchereau J, 2001. Lipopolysaccharides from distinct pathogens induce different classes of immune responses in vivo. J. Immunol 167, 5067–5076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymond CR, Wilkie BN, 2005. Toll-like receptor, MHC II. B7 and cytokine expression by porcine monocytes and monocyte-derived dendritic cells in response to microbial pathogen-associated molecular patterns. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol 107, 235–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Re F, Strominger JL, 2001. Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) and TLR4 differentially activate human dendritic cells. J. Biol. Chem 276, 37692–37699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehli M., 2002. Of mice and men: species variations of Toll-like receptor expression. Trends Immunol. 23, 375–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren WY, Zhu L, Hua F, Jin JJ, Cai YY, 2010. The effect of lipopolysaccharide on gene expression of TLR4 and MD-2 in rat alveolar macrophage and its secretion of inflammation cytokines. Zhonghua Jie He He Hu Xi Za Zhi 33, 367–371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozen S, Skaletsky H, 2000. Primer3 on the WWW for general users and for biologist programmers. Methods Mol. Biol 132, 365–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siednienko J, Miggin SM, 2009. Expression analysis of the Toll-like receptors in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Methods Mol. Biol 517, 3–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen NS, Skovgaard K, Heegaard PM, 2011. Porcine blood mononuclear cell cytokine responses to PAMP molecules: comparison of mRNA and protein production. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol 139, 296–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorgersen EB, Hellerud BC, Nielsen EW, Barratt-Due A, Fure H, Lindstad JK, Pharo A, Fosse E, Tonnessen TI, Johansen HT, Castellheim A, Mollnes TE, 2010. CD14 inhibition efficiently attenuates early inflammatory and hemostatic responses in Escherichia coli sepsis in pigs. FASEB J. 24, 712–722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tirumurugaan KG, Dhanasekaran S, Raj GD, Raja A, Kumanan K, Ramaswamy V, 2010. Differential expression of toll-like receptor mRNA in selected tissues of goat (Capra hircus). Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol 133, 296–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uddin MJ, Cinar MU, Tesfaye D, Looft C, Tholen E, Schellander K, 2011. Age-related changes in relative expression stability of commonly used housekeeping genes in selected porcine tissues. BMC Res. Notes 4, 441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uenishi H, Shinkai H, 2009. Porcine Toll-like receptors: the front line of pathogen monitoring and possible implications for disease resistance. Dev. Comp. Immunol 33, 353–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yancy H, Ayers SL, Farrell DE, Day A, Myers MJ, 2001. Differential cytokine mRNA expression in swine whole blood and peripheral blood mononuclear cell cultures. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol 79, 41–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youn JH, Oh YJ, Kim ES, Choi JE, Shin JS, 2008. High mobility group box 1 protein binding to lipopolysaccharide facilitates transfer of lipopolysaccharide to CD14 and enhances lipopolysaccharide-mediated TNF-alpha production in human monocytes. J. Immunol 180, 5067–5074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Guo Y, Lv K, Wang K, Sun S, 2008. Molecular cloning and functional characterization of porcine toll-like receptor 7 involved in recognition of single-stranded RNA virus/ssRNA. Mol. Immunol 45, 1184–1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J, Lai K, Brownile R, Babiuk LA, Mutwiri GK, 2008. Porcine TLR8 and TLR7 are both activated by a selective TLR7 ligand, imiquimod. Mol. Immunol 45, 3238–3243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.