Abstract

We use a microfluidic ecology which generates non-uniform phage concentration gradients and micro-ecological niches to reveal the importance of time, spatial population structure and collective population dynamics in the de novo evolution of T4r bacteriophage resistant motile E. coli. An insensitive bacterial population against T4r phage occurs within 20 hours in small interconnected population niches created by a gradient of phage virions, driven by evolution in transient biofilm patches. Sequencing of the resistant bacteria reveals mutations at the receptor site of bacteriophage T4r as expected but also in genes associated with biofilm formation and surface adhesion, supporting the hypothesis that evolution within transient biofilms drives de novo phage resistance.

1. Introduction

Bacteriophages (phages) are viruses that infect bacteria. Phages coexist with microbes, playing a fundamental role in microbial diversity, population dynamics and evolution. Understanding the interaction between phages and bacteria gives us fundamental information on ecological and evolutionary processes [1]. Phages can be divided into two classes: temperate and virulent. The life history for temperate phages typically consists of two parts: a lysogenic phase after inserting their DNA into the genome of a host bacterium after infection, and a propagating lytic phase where they extract their genome from the host genome, reproduce within the bacterium and exit by lysis of the bacterium. Virulent phages only have a lytic cycle; they do not insert their DNA into the host but rather use the cell’s machinery to make copies and lyse the cell.

Bacteriophage T4 can pause cell lysis in super-infected bacteria to yield very high titer yields in the lysis of remaining bacteria. The T4 phage strain used in this study is highly virulent and rapidly lyses the cell after infection (it is an obligate lytic, [2]). Phage T4r (T4 rapid) lacks the lysis inhibition (LIN) genes of wild-type T4 and rapidly lyses bacteria, even multiply infected “super-infected” bacteria, with resultant relatively low titer yields compared to wild-type T4 [3]. Because of the rapid lysis of T4r infected bacteria any survival of a low number NO of bacteria can only be due to either previously acquired resistance (Darwinian random mutations) or a kind of rapid response by the stress-challenged bacteria, which can be called Lamarckian in a certain sense of the word.

In the 1940s the pioneering studies of Luria and Delbrück [4] explored phage resistance to the obligate lytic phage T1 in E. coli using a protocol of well-mixed culture flasks and plaque formation assays on agar. These studies were interpreted to show that bacterial mutations giving resistance occurred in the absence of selective pressure rather than being a response to it, contradicting the Lamarckian acquired evolution hypothesis which at the time suggested that specific mutations are acquired specifically in response to certain environmental stresses. Luria and Delbrück proved that pre-existing mutations conferring resistance were present in a sufficiently large bacterial population. However, they did not disprove the possibility that acquired resistance in response to stress [5] might also occur and contribute to the emergence of resistance [6]. Furthermore, the homogeneous low-stress environment of a well-mixed culture flask does not resemble the complex ecologies in which bacteria typically grow, and they do not allow for bacterial motility across ecological regions with differing stress levels and the spread of resistance from de novo mutational response to phage infection [7].

Since then, we have learned that mutations in response to stress do occur [8] and that there are different ways for organisms from bacteria to man to acquire heritable phenotypic changes upon transient exposure to stress [9, 10]. We also know that both genome-wide mutation rate and the mutation rates of specific genes can be affected by the environment [11–13]. Furthermore, the complexity of the environment (e.g., compartmentalization) might facilitate the fixation of mutations in bacterial populations [14, 15]. In the past decade more and more papers highlighted the importance of spatial variations in antibiotic concentration gradients in the evolution of bacterial antibiotic resistance [16–19]. We have shown in a previous publication that stress gradients imposed over a metapopulation of weakly coupled communities can greatly increase the rate at which resistance evolved to the mutagenic antibiotic ciprofloxacin [18].

In this study, we examine how stress gradients have an impact on the emergence of phage resistance in small interconnected E. coli populations with time. Bacteria can develop resistance de novo against phage infections in different ways: by gene mutations and by an ”adaptive immune response” using the CRISPR-Cas system to detect and destroy DNA from similar viruses during subsequent infection [20,21]. Laboratory strains of E. coli possess a functional CRISPR-Cas system, however, this system seems to be ”silent” under normal laboratory conditions [22, 23]. Although E. coli is an important model organism for the characterization of the CRISPR-Cas systems, and detailed descriptions of its structure and molecular mechanism in this species can be found in the literature [24–26], the physiological conditions needed for its activation is still unclear and it needs to be further investigated.

For a realistic bacterial-phage scenario it is important to try and replicate the natural habitats of microorganisms, which are complex - the environments have physical heterogeneity and heterogeneous distribution of resources. However, most studies have been carried out in well-mixed populations or chemostats [27] or on agar plates with homogeneous phage concentrations. These studies do not capture some important complexities of natural communities (e.g. spatial [28] and temporal [29] heterogeneity). Microfluidics provide excellent tools to mimic such aspects of natural habitats and study questions related to microbial ecology [30]. For example, a microfluidic mother machine study revealed the importance of the presence of spatial refugees in an E. coli population against bacteriophage T4 in structured environments compared to well-mixed cultures [31]. They suggest that structured environments promote the selection of phenotypic variants with low phage receptor expression.

In this paper, we aim to shed light on the fundamental processes behind the evolution of bacteriophage resistance. We use a microfabricated environment in which we exposed motile E. coli bacteria to spatial gradients of T4 bacteriophage T4r (The “r” in T4r denotes a mutation that leads to rapid lysis of the bacterial host) which reproduce by the lytic cycle when infecting E. coli. The growth and distribution of the bacterial population were followed in time by fluorescence time-lapse microscopy. Resistant cells were collected from the microfluidic device for further analysis, e.g., genomic sequencing was performed to identify key mutations leading to the observed resistance.

2. Methods

Culturing bacteria and phage

Bacteriophage T4r (Carolina Biological Supply Company) and E. coli AD62 strain were used in the experiments. AD62 is derived from the K-12 strain AB1157 [32] that has the λ-deficiency, which makes it a suitable host for the T4r phage we used in our experiments. The E. coli strain was transformed with the pWR21 plasmid [33] for constitutive green fluorescent protein (eGFP) expression. The bacteriophage concentration was 2×109 virus particles/ml in the experiments. The proper phage concentration was measured by standard PFU assay.

Before each experiment bacteria were grown overnight in plastic tubes using 2 ml lysogeny broth (LB) medium supplemented with 100 μg/ml ampicillin at 37 °C in an incubator shaker (200 rpm). Overnight cultures were diluted back in the morning, and cells at a concentration of OD600=0.6 (optical density measured at 600 nm) were used for the inoculation of the microfluidic device. The number of N bacteria/ml at OD600=0.6 is approximately 2×108/ml determined by CFU assay. The volume of the center well of the device is approximately 4×10−2 μl. Thus, we predict and can confirm that we inoculated the center well with approximately Ni = 104 bacteria at t = 0.

After the experiments resistant cells were isolated by opening the device and using the silicon part for replica plating on agar plates that were previously coated by 109 particles of T4r [4, 34]. The selection plates with the imprints of the device were incubated overnight (16 h) at 37 °C. Colonies were picked from the regions of the imprint where resistant growth was observed and further analyzed. The key parameter is the spontaneous rate of single-nucleotide polymorphisms in unstressed E. coli ΘD ≈ 2.0×10−9/generation [35].

Optical density measurements (at 600 nm) were carried out to characterize the growth of the wild type E. coli strain and the mutants isolated from the experiments. The optical density was measured in 110 μl volumes in 96-well plates by using a BioTek Synergy H1 microplate reader. Overnight cultures (2 ml LB, plastic tubes, 200 rpm, 37 °C) were backdiluted in the morning 500 times. When the optical density of the cultures reached 0.6, 100 μl of the bacterial cultures (with or without dilution) together with 10 μl of bacteriophage solution (with the appropriate phage concentration) were measured into the wells. The duration of the plate reader experiments were 24 hours, the well plate was shaken continuously (double orbital, 425 cpm frequency), and the temperature was set to 37 °C. Optical density was measured every 5 minutes.

The surface-adhered biofilm-forming ability of the ancestral and mutant strains was tested using the microtiter plate biofilm assay (based on crystal violet staining) [36]. The assay was performed in a 96-well plate. 100 μl of cell cultures (OD=0.6, in LB) were loaded in each well and incubated for 48 hours at 37 °C without phage. Three replicates were made for each sample.

Microfluidic device setup

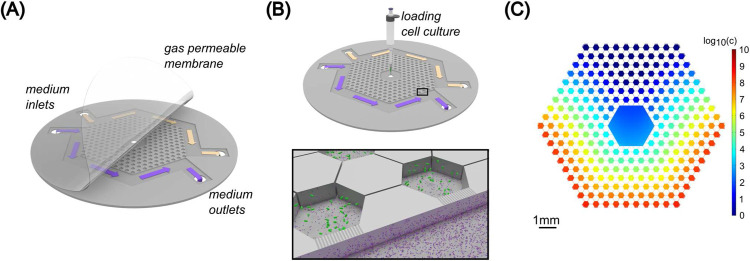

We used the basic hexagon array of gradient microhabitats used in [18]. The microfluidic device was etched in two layers into a silicon wafer. The schematic representation of the device is presented in Fig. 1. It is a network of hexagonal wells that are connected through narrow channels etched to 10 μm depth. The nutrient supply of this network is provided from two side channels that are connected to the outer wells through 100 nm deep nanoslits. The total etched area of the hexagon array is approximately 40 mm2.

Figure 1.

Microfluidic setup. A) 3D drawing of the microfluidic device (not-to-scale). The etched silicon chip is sealed with a 25 μm thick gas permeable LUMOX film, pressurized from the front. Arrows indicate the direction of medium flow. Yellow color is used for pure LB (top channel) and the purple color corresponds to LB supplemented with T4r phages (bottom channel). B) Mounting of the chip in a LUMOX dish with applied external sealing back air pressure. Bacteria are inoculated into the middle inlet hole with a pipette. The inset shows the phage (purple particles) gradient forming from the bottom channel. Shallow (100 nm deep) nanoslits connect the side channels and the outer hexagon chambers. C) Simulation of the phage gradient present in the device at the initial stage of the experiment. Phage concentration c is indicated by the colorbar in logarithmic scale. The unit of c is virion/ml.

The top of the etched device is reversibly sealed by a 25 μm thick gas-permeable Lumox membrane (SARSTEDT AG & Co. Nümbrecht, Germany). Sealing of the device top was done by pressurizing the outside of the structure with atmospheric composition air at 2×104 Pa. This sealed the film against the silicon wafer but did not close the 100 nm deep etched nanoslits of the device. However, as we discuss in the text, the finite pressure of the sealing film sometimes allowed bacteria to form highly condensed colonies by pushing the film up.

Medium mixed with phage flow was provided by syringe pump at 5 μl/h throughout the experiments. Before each experiment, the chip was run with LB medium (supplemented with 100 μg/ml ampicillin) and bacteriophage T4r in one of the side channels (always the bottom one in the images) for 20 hours to ensure an initial virus gradient and nutrient concentration within the device. The highest phage concentration applied in the side channel was 2×109 virus particles/ml. The concentration of bacteriophage within the microfluidic device was calculated for a full 3D model with COMSOL Multiphysics 4.3a software (COMSOL AB, Stockholm, Sweden) over the timescale of the experiment. The diffusion constant of the phage was estimated to be 8×10−8cm2/s [37,38]. Bacteria were inoculated into the middle of the device with a pipette at 104 cell number into the 0.04 μl volume of the inlet hole. Experiments (three biological replicates) were carried out at 30 °C.

Image acquisition

Fluorescence time-lapse microscopy was performed by using a Nikon TE2000-E inverted microscope and a Canon camera (EOS5d). To get a high-resolution image series, in one experiment we used a Nikon 90i upright microscope supplemented with an ANdor Neo 5.5 sCMOS camera and a 4X Plan APO λ objective. Figures in the paper were prepared using the high-resolution image series. In both setups, a GFP filter set was used to monitor the growth and spatial distribution of bacterial populations within the device. μManager and NIS Elements software were used to take images every 15 minutes.

Whole genome sequencing

Resistant cells were collected after the experiments on selection plates and clones were further analyzed by whole genome sequencing (The Sequencing Centre, Fort Collins, CO 80524, USA). Total DNA was extracted by using the Zymo Research Quick-DNA Fungal/Bacterial Microprep Kit (Catalog No. D6007) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The Illumina (illumina.com) Nextera XT DNA Library Prep Kit was used to prepare extracted bacteria DNA for sequencing. Bacterial whole genome sequencing was performed on an Illumina MiniSeq short-read sequencer using a standard Illumina workflow and configured for 2 × 150 bp paired-end reads and MiniSeq flow cell.

The sequenced samples included one clone of the ancestral strain and three clones isolated from the experiments. We identified mutations related to T4 phage resistance and examined whether the CRISPR-Cas defense mechanism of E. coli -that is mostly repressed in lab cultures [39] - was activated under such circumstances. The raw sequences have been deposited under the study number PRJEB73316 at the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA). Paired-end sequencing with 150 bp read length was used to generate reads. Quality assessment was carried out with FastQ [40]. We trimmed raw reads to remove adapter sequences and PhiX174 contamination using BBduk. Sequence reads were assembled using Unicycler (version v0.4.7) [41]. The assembled sequences were annotated with Prokka (version 1.14.6) [42]. BBMap utilities were applied to obtain assembly metrics’ statistics [43, 44]. The annotated genomes were compared to identify the missing genes across the strain and mutants using Roary [45]. We identified SNPs in the mutants by mapping the reads to the wild-type strain using Breseq (version: 0.35.4) [46].

3. Results

Colonization of the microstructured habitat by motile bacteria in the presence of phage gradient

A microfabricated landscape was used to study the evolution of bacteria against lytic phages. The microfluidic device consisted of a network of hexagon microchambers that were connected through narrow corridors (see Methods). Nutrient supply was ensured by a constant flow of fresh LB medium in the side channels that were connected (by nanoslits) to the outer patches (Fig. 1A–B). Motile E. coli cells were inoculated into the inlet hole positioned at the center of the device and can move between the microchambers and find the most favorable conditions. In the absence of any phage gradients, bacteria form chemotactic waves [47] and move over to the nanoslits which act as nutrient sources in this system. This rapid chemotaxis (which takes a couple of hours) towards the nanoslits occurs because of the extremely small volume (approximately 0.4 μl) of medium within the hexagon array, and the rapid local consumption of nutrients by bacteria.

In our experiments, we set up an initial T4r phage gradient across the hexagon array, thus the inoculated bacteria were immediately in contact with lytic T4r phage. The initial distribution of phages in the microfluidic device, in the case of flowing LB medium supplemented with phages (2×109 virus particles/ml concentration) in the bottom side channel, was estimated by a 3D model and is presented in Fig. 1C. Based on our simulations, this is not a steady state, the gradient slowly changes throughout the experiment. Also, the lysis of bacteria infected by phage disturbs the phage gradient in the later phase of the experiments. The local increment of phage concentration upon lysis events is not included in the 3D model, but it represents well the initial microenvironment.

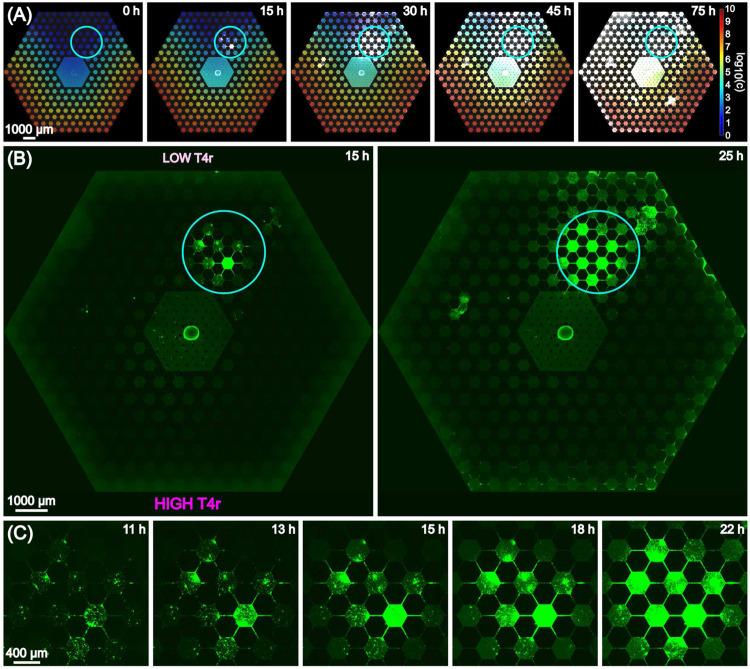

Fig. 2 shows the basic progression of motile E. coli in the device. In the case of T4r phage gradient the previously mentioned fast chemotactic waves were lacking. Instead, localized emergence of insensitive sub-populations at low-intermediate phage concentrations within 24 hours was the typical response we observed. Fig. 2A shows fluorescence snapshots overlaid on top of the calculated concentration profile over the 75-hourlong experiment. Supplementary movie 1 contains the entire time-lapse image series of the experiment. The ”hot-spot”, which refers to the location where the insensitive population starts intense growth and colonization, is outlined by the solid circle in Fig. 2A,B, whereas Fig. 2C shows zoom-in images of this region. We can see aggregation of cells and the formation of small clusters from which bacteria spread to other parts of the device as well Fig. 2B,C. Note, that in Fig. 2B it can be seen that after 25 hours single cells also appear at the nanoslits even at the high phage concentration side of the hexagon array.

Figure 2.

Progression of bacterial growth in T4r phage gradient. The emergence of an insensitive population at the low-phage concentration side of the device is outlined by a solid circle. (A) Snapshots of fluorescence microscopy images overlaid on the calculated T4r concentration gradient over a period of 75 hours. Phage concentration (c) is represented in logarithmic scale. The unit of c is virion/ml. (B) Stitched image of the full microfluidic array from 15 hours to 25 hours after inoculation. The solid blue circle outlines the hot spot of the insensitive bacterial population against T4r phage. (C) Emergence of insensitive sub-population from small clusters of bacteria over a time scale from 11 hours to 22 hours

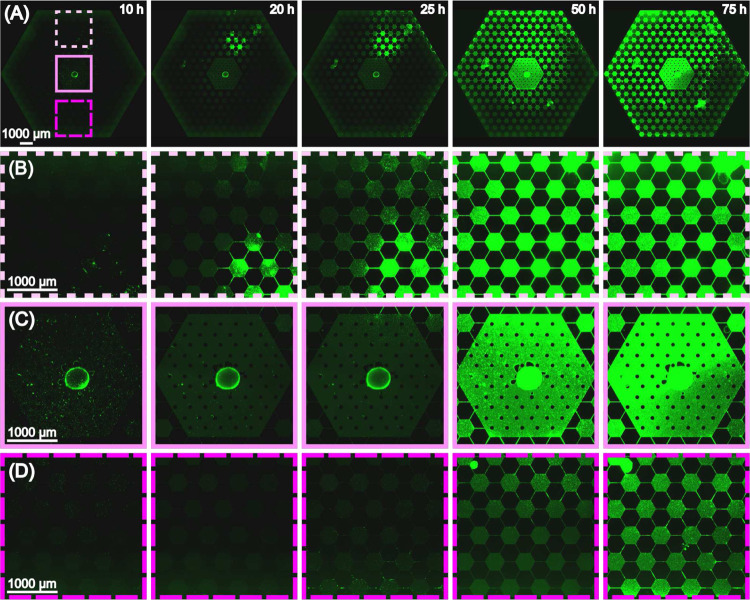

The observed progression pattern is the result of different mechanisms: (1) chemotaxis towards the nutrient sources, (2) response to the stress exposed by phage. The latter one might imply e.g. producing extracellular materials, biofilm formation or the appearance of stress-induced mutations in the complex environment. The details of the progression is presented in the fluorescence images of Fig. 3 by zooming into the different regions (with different phage concentrations) of the microarray habitat over the time scale of an experiment (same as presented in Fig. 2). Fig. 3 shows that after 10 hours there are bacteria in the outer hexagon chambers (right next to the nanoslits). Bacteria spread fast on the phage-free/low-phage concentration side of the habitat. However, cells (mostly single cells) can be detected on the high phage concentration side as well within 10 hours. Fig. 3A and Supplementary Movie 1 shows that 48 hours is enough for the population to colonize the the whole habitat. However, black areas can be clearly identified in the landscape (Fig. 3A) that probably represent regions of lyzed cells as a consequence of local phage infections. Occasionally, bacteria form such dense biofilm-like structures that slightly lift the sealing membrane. This was not observed before when using the same setup in evolution studies against antibiotics [18].

Figure 3.

(A) Stitched images of the full array from 10 hours to 75 hours after inoculation. The dashed and solid squares outline regions of the habitat with different phage concentrations. (B) Zoom-in images of the top region of low T4r density.(C) Zoom-in images at the inoculation region in the center of the device. (D) Zoom-in images of the bottom region of high T4r density.

Characterization of bacteria extracted from the microarray habitat

Three biological replicates were performed and the dynamics of the bacterial populations in the bacteriophage stress landscape were followed over 3–4 days. In all cases, the insensitive sub-populations appeared within a day and the basic progression pattern was very similar to what is described and presented in Fig. 3. After each experiment, the device was taken apart to collect cells. For this purpose, the Lumox cover of the ecology was removed from the silicon and resistant clones were isolated using selection plates (see Methods). Three colonies were randomly selected for further analysis. The growth properties and whole-genome sequencing data were compared to the ancestor E. coli strain (see Methods).

The results of whole-genome sequencing confirmed the presence of mutations related to phage resistance in the cells that were exposed to the T4r phage gradient during the experiments. The relevant mutations are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of the relevant mutations found in resistant mutants extracted from the microfluidic device after exposure to a gradient of T4r

| Sample | Gene | Description | Mutation |

|---|---|---|---|

| mutant1 | ompC | outer membrane protein C | MC (8bp) |

| csgB | minor curli subunit | MC (526bp) | |

| csgD | CsgBAC operon | MC (155bp) | |

| mutant2 | csgB | minor curli subunit | MC (482bp) |

| csgD | CsgBAC operon | MC (155bp) | |

| rfaP | outer membrane lipopolysaccharide core | MC (218bp) | |

| rcsC | sensor histidine kinase RcsC | T →G (CTG →CGG |

|

| mutant3 | ompC | outer membrane protein C | +T (TAT →TTT) |

| rfaP | outer membrane lipopolysaccharide core | MC (218bp) |

The most obvious mutations related to T4r resistance occurred at the receptor site of bacteriophage T4 (ompC) [48–50]. Two out of the examined three isolates (mutant1 and mutant3 in Table 1) had changes in this particular gene, which could serve as a primary defence mechanism by inhibiting phage adsorption. The other detected mutations could also contribute to the reduced entry of the phage into the cell, and most of them can be associated with the adhesion properties and biofilm-forming abilities of E. coli. E.g., the rfa locus is important in the barrier function of the outer membrane. rfaP is involved in the pathway of the LPS core biosynthesis [51]. Besides rfaP, mutations were detected in csgB, csgD, rcsC, which are important in the normal biofilm formation of E. coli [52, 53]. In two samples (mutant1 and mutant2) both csgB and csgD were altered. These genes have a crucial role in the expression of curli fimbrae and possess a positive role in biofilm formation [54]. rcsC is associated to mucoid phenotype and to normal biofilm formation on solid surfaces [55]. It is also involved in colanic acid synthesis. Indeed, mutant2 having an SNP in rcsC, has a mucoid phenotype when forming colonies on a hard agar surface. The sequencing results together with the time-lapse images (Fig. 2 and Fig. 3) suggest that biofilm formation has a crucial role in bacterial phage resistance.

In the past decade, the role of clustered regulatory interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR) and the associated cas genes in resistance against phages got acknowledged [20]. The activity of the CRISPR system of E. coli had not been reported previously under normal laboratory conditions. However, we were curious if the structured landscape we designed could somehow induce it. For this purpose, we compared the CRISPR regions of the isolates to the ancestor strain. No changes could be detected in the spacer sequences.

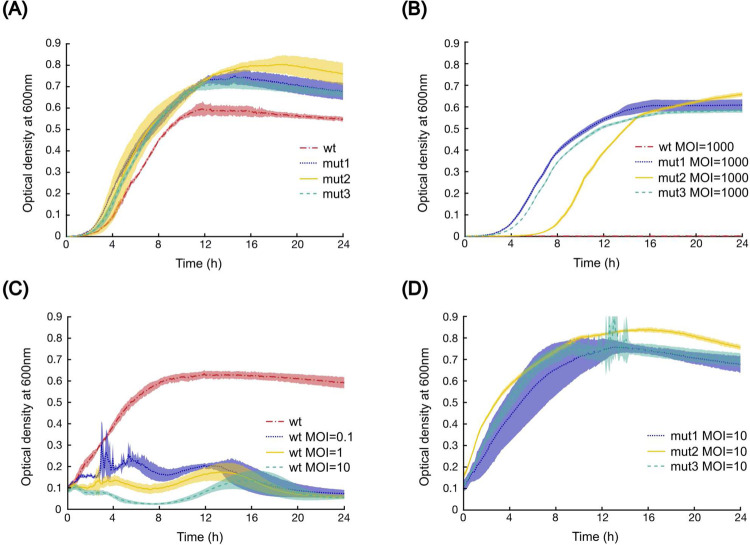

The growth properties of the mutants in the presence and absence of T4r were compared to the ancestor strain by measuring the optical density of cell cultures in 96-well plates (see Methods). Fig. 4A shows that there was no apparent fitness cost to achieving T4r resistance. The growth curves of the mutants are similar regardless of the presence of the phage (Fig. 4A,B).

Figure 4.

Growth properties of the ancestor and three mutant E. coli strains. (A) Growth of the ancestor (red dashed line) and three mutant (mut1: dotted blue line; mut2: continuous yellow line; mut3: dashed green line) strains in phage-free LB media. (B) Growth of the ancestor (red dashed line) and 3 mutant (mut1: dotted blue line; mut2: continuous yellow line; mut3: dashed green line) strains in the presence of high phage concentration (MOI=1000, the initial cell number is 100000). (C) Growth of the ancestor strain in LB media at different MOI. T4r was added to mid-log phase bacteria culture, the initial bacteria cell number is 10000000. (D) Growth of the three mutant strains when applying phage (MOI=10) at mid-log phase culture. The initial cell number is 10000000 (mut1: dotted blue line; mut2: continuous yellow line; mut3: dashed green line).

The high-level resistance against T4r is shown in 4B, where the bacteria-phage cultures were started by applying MOI=1000. Under such circumstances, the growth of the ancestor strain was completely excluded. Addition of T4r to a growing culture of the ancestor bacterial strain at mid-log phase at lower MOI values (from 0 to 10) results in no change to the further growth of the resistant strain but the lysis of wild-type bacteria, as shown in Fig. 4C,D.

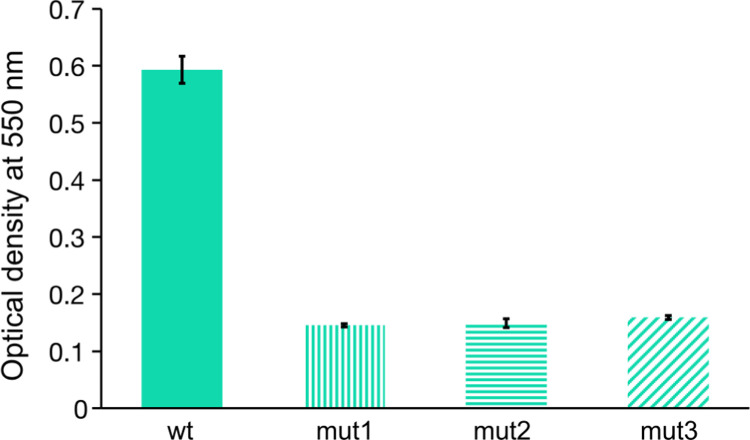

The presence of mutations in csgB, csgD and rcsC genes, suggest that the mutants show differences in biofilm-forming and surface adhesion properties compared to the ancestor strain. Therefore, we probed the mutant strains for their ability to form surface-adhered biofilms using the crystal violet staining protocol [36]. Interestingly, as shown in Fig. 5, the mutant strains had substantially reduced biofilm-forming ability, indicating that the reduction in phage sensitivity also resulted in reduced ability to form surface-adhered biofilms.

Figure 5.

Biofilm forming ability of the ancestral and the mutant strains evolved in the microfluidic device in the presence of bacteriophage T4r gradient. The applied crystal violet staining shows the amount of surface-adhered biofilm after 48 hours of incubation at 37°C. Three replicates were performed for each sample.

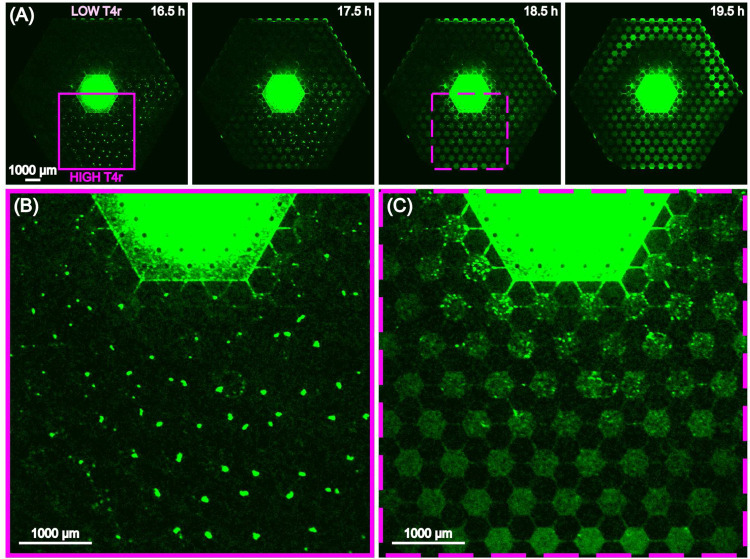

Inoculation of the resistant bacteria into the same complex ecology (with T4r gradient) that resulted in the evolution of the resistant strain shows a more nuanced picture of the changed growth properties of the mutants than the 96 wellplate experiments of Fig. 4. Fig. 6 and supplementary movie 2 shows the rather complex response of the mutant strain in a T4r gradient and a set of connected habitats. At the low T4r titer side as expected we see movement to the nanoslits and growth, Fig. 6A. At the intermediate and high titer concentrations, we see a transient aggregation of the bacteria into small clusters within each microhabitat for a period of several hours, followed by the dissolution of the clusters and uniform growth even at high titers of T4r (Fig. 6B, C). The chemotactic waves - that are typical for E. coli - were also present under such circumstances.

Figure 6.

(A) Expansion of resistant E. coli in a gradient of T4r phage from 16.5 hours after inoculation to 19.5 hours. (B) Expanded view at 16.5 hours of the region at high T4r concentration where the bacteria transiently form small clusters. (C) Rapid dissolution of the bacterial aggregates and movement to nanoslits.

4. Mutations rates and evolution concepts

The ultimate observance of phage T4r resistant bacteria has three possibilities: (1) What are the odds that the initial inoculate of bacteria in the test tube had preexisting T4r resistant bacteria?; (2) What are the odds that the test tube from which we drew No bacteria spontaneously evolved resistant bacteria in the absence of T4r and we inoculated resistant bacteria into the device?; (3) What are the odds that during the time that the bacteria grew in our device that a mutation occurred that gave rise to resistance due to contact with phage? These three questions get to the heart of the conflict between viewing all resistance as being spontaneously derived without exposure (“Darwinian”) or viewing resistance emergence as a sum of Darwinian spontaneous evolution and stress-induced mutations (“Lamarckian”).

Holmes et al. [6] have carried out an extensive analysis of the original Delbrück-Luria experiments and have included both spontaneous (“Darwinian”, ΘD) and in stress response (“Lamarckian”, ΘL) mutation rates in what they called a Composite model which included both mutation mechanisms. Based on their calculations the pure Lamarckian model is inconsistent with the experimental data (as expected), but the Composite model (containing both mechanisms) and the pure Darwinian model fit equally well. As Holmes et al. point out, the dynamics of such an evolving and reproducing system is quite complex, there exist no analytical solutions. In the followings we give an estimation of mutation rates in our own experimental setup.

We can make some simple assumptions to guess how many pre-existing mutants were in our original inoculation. In a “worst case” scenario, assume that a single but specific basepair mutation suffices to give phage resistance (but see below, the number is larger). If we start with No bacteria and end with N bacteria, the total number of bacteria that ever lived is 2N − No. In the absence of stress (no phage contact) the spontaneous mutation rate is ΘD ~ 10−9 basepairs/generation [35]. This means that for a single resistant mutation (as opposed to any mutation), in the first generation ΘDNo are resistant, and No(2 − ΘD) are sensitive. After a total of G generations we will have [No(2 − ΘD)]2G−1 sensitive mutants, and (ΘDNo)2G−1 resistant ones. It is possible to then continue down this line from generation to generation, in each generation of No2g−1 total bacteria we again get θDNo2g‒1 resistant mutants, assuming that the pool of sensitive bacteria has not changed greatly due to ΘD << 1. Under the assumption of a relatively unchanged pool for mutants from generation to generation, we sum to get the total number of resistant mutants Nr starting with No sensitive mutants in G generations:

| (1) |

This yields for the fraction of bacteria that have resistance due to purely spontaneous mutations ΘD after G generations:

| (2) |

Thus, only GΘDNo bacteria would have been expected to be already resistant due to spontaneous (Darwinian) mutations. In our case G ~ 24 for the initial expansion, the number of expected already resistant bacteria in the initial inoculation of No ~ 104 bacteria is vanishingly small, while we saw resistance emerge with prolonged phage exposure (unlike Delbrück Luria experimental protocol) in each experiment.

We can attempt a very rough estimate of the stress-induced (Lamarckian) mutation rate ΘL in a similar way, again in the assumption that only 1 mutation can give rise to resistance (which is not the case, as gathered from our sequencing results). In the chip we incubated against T4r phage for approximately 15 hrs before the growth of an insensitive population was observed, or roughly 30 generations, starting with No ~ 104. Assuming we see at least 1 resistant mutant in 30 generations, this yields the mutation rate ΘL:

| (3) |

This is a vastly higher rate than the Darwinian rate ΘD. However, it is not unprecedented given the role the SOS response and presumable hypoxic conditions in biofilms that we observe can provide in accelerating mutation frequencies [56].

Our experiments ran for 3 days before bacteria were collected from the device and further analyzed. Therefore, it is also worth mentioning the stress-induced mutation rate calculated in the same way for 72 hours (roughly 140 generations). That is ~ 10−6, which is still order of magnitudes higher than the spontaneous ΘD mutation rate.

5. Discussion

Bacteria and phages coexist in nature performing a continuous co-evolutionary co-existence. As part of this evolutionary co-existence, bacteria have evolved different mechanisms to survive phage infections and the phage have evolved mechanisms not to destroy their hosts, whom they need.

The natural environment of the perhaps somewhat onesided but still symbiotic relation between phage and bacteria [57] is not the well-stirred chemostat of the microbiology laboratory [58]. Spatial and temporal inhomogeneities in the distribution of stress factors (selection pressure) have a profound impact on evolutionary processes, changing population numbers and the invasion of resistant strains into sensitive ones. Understanding how the environment and ecology can change both mutation rates and selection dynamics is important to properly describe evolutionary processes [59].

Typically bacterial strategies for survival in complex environments involve both phenotypic and genetic adaptations. In terms of genetic adaptation, ordinarily E. coli have a remarkably faithful DNA replication system with an error rate on the order of 10−9/bp/generation [60] in the absence of stress. In our previous antibiotic evolution experiments we triggered the highly error-prone DNA replication response of the SOS system in E. coli [61], driven by the appearance of singlestranded DNA due to gyrase A blockage by ciprofloxacin, to form the driver of rapid evolution. The formation of filamentous bacteria [62] was an indication that this heightened evolution acceleration is occurring [63].

For phage T4r there is no corresponding SOS response to provide and evolution exit to stress via enhanced mutation rates. Apparently, at least for T4r, phage exposure alters different phenotypes, including in our case transient biofilm formation. Growing evidence shows that bacteriophages can modulate biofilm development [64], but these studies mostly deal with lysogenic phage and not virulent ones. The influence of virulent phages on biofilm formation is more limited and mostly relates to the study of the eradication of biofilms with high-phage titers.

The genetic response of bacteria in our device was heterogeneous and varied from run to run, although there were unifying themes. For example, observed mutations in the RcsC system are plausible since the Rcs signalling system controls the transcription of numerous genes involved in biofilms, e.g. genes that are involved in colanic acid capsule synthesis, production of cell surface-associated structures (flagella, LPS, fimbriae), biofilm formation and cell division [65]. RcsC is an important part of this system, functions as a membraneassociated protein kinase, and it is activated during growth on a solid surface [66]. In E. coli, Poranen et al. observed upregulation of genes necessary for capsule synthesis (RcsA) at 10 minutes post-infection [67]. Exopolysaccharide induction and colonic acid synthesis is a typical defense mechanism that protects the bacterial population but seems to be jettisoned once resistance is developed.

In our experiments, the CRISPR-Cas system of E. coli did not turn on, which is in good agreement with the literature. Efficient protection against phages by CRISPR/CAS-E has not been observed in the non-manipulated wild-type E. coli K12 strain. The Cascade (CRISPR-associated complex for antiviral defence) genes form an operon whose expression is repressed under normal laboratory growth by the transcriptional regulator H-NS (histone-like nucleoid structuring protein) [22,23]. It is not known what physiological circumstances are needed to turn it on.

There is a movement now to re-develop phage therapy [68] as an alternative to antibiotics because of the emergence of “super-bugs” with Multi-antibiotic resistance [69]. However, we would caution that because of our observed fast emergence resistance in a structured environment designed to award mutants with fitness-enhancing adaptions, successful therapeutic applications must be carefully designed to account for deep changes in evolution dynamics that can occur in complex environments [70] and the passage of time to phage exposure [71].

6. Conclusions

The widespread emergence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria has led to a resurgence in interest in phage therapy to control bacterial infections [72]. However, our study shows that the rapid emergence of stress-induced phage resistance can also occur, as perhaps one would expect given the long co-existence of phage with bacteria. We show that while our mutant resistant E. coli have expected mutations in the T4 OmpC binding site, they also have mutations in genes associated with biofilm mechanics, which based on our observations of the emergence of resistance in our microecologies is expected. Alas, the mutagenic mechanism driving this resistance acceleration in our hands remains unknown.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NSF PHY-1659940. KN was supported by the Fulbright Program and the Hungarian Academy of Sciences.

Footnotes

Additional Declarations: There is NO Competing Interest.

Data availability statement

The data generated in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The raw sequences are available at the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA) database under the study number PRJEB73316.

References

- [1].Pires D. P., Melo L. D. R., and Azeredo J.. Understanding the complex phage-host interactions in biofilm communities. Annu Rev Virol, 8(1):73–94, 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Carlson K. and Kozinski A. W.. Nonreplicated dna and dna fragments in t4r-bacteriophage particles - phenotypic mixing of a phage protein. Journal of Virology, 13(6):1274–1290, 1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Burch L. H., Zhang L. L., Chao F. G., Xu H., and Drake J. W.. The bacteriophage t4 rapid-lysis genes and their mutational proclivities. Journal of Bacteriology, 193(14):3537–3545, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Luria S. E. and Delbruck M.. Mutations of bacteria from virus sensitivity to virus resistance. Genetics, 28(6):491–511, 1943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Jablonka E. and Raz G.. Transgenerational epigenetic inheritance: Prevalence, mechanisms, and implications for the study of heredity and evolution. Quarterly Review of Biology, 84(2):131–176, 2009. 446lx Times Cited:935 Cited References Count:236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Holmes C. M., Ghafari M., Abbas A., Saravanan V., and Nemenman I.. Luria-delbruck, revisited: the classic experiment does not rule out lamarckian evolution. Physical Biology, 14(5), 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Correa A. M. S., Howard-Varona C., Coy S. R., Buchan A., Sullivan M. B., and Weitz J. S.. Revisiting the rules of life for viruses of microorganisms. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 19(8):501–513, 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Wang X., Liu Y., Li K. Y., and Hao Z. H.. Roles of p53-mediated host-virus interaction in coronavirus infection. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 24(7), 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Chapelle V. and Silvestre F.. Population epigenetics: The extent of dna methylation variation in wild animal populations. Epigenomes, 6(4), 2022. 7g2pk Times Cited:0 Cited References Count:148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Pribis J. P., Zhai Y., Hastings P. J., and Rosenberg S. M.. Stress-induced mutagenesis, gambler cells, and stealth targeting antibiotic-induced evolution. Mbio, 13(3), 2022. 2u3oc Times Cited:0 Cited References Count:168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Wielgoss Sébastien, Barrick Jeffrey E., Tenaillon Olivier, Wiser Michael J., Dittmar W. James, Cruveiller Stéphane, Chane-Woon-Ming Béatrice, Médigue Claudine, Lenski Richard E., and Schneider Dominique. Mutation rate dynamics in a bacterial population reflect tension between adaptation and genetic load. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 110(1):222–227, January 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Tenaillon Olivier, Denamur Erick, and Matic Ivan. Evolutionary significance of stress-induced mutagenesis in bacteria. Trends in Microbiology, 12(6):264–270, June 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Richard Moxon E., Rainey Paul B., Nowak Martin A., and Lenski Richard E.. Adaptive evolution of highly mutable loci in pathogenic bacteria. Current Biology, 4(1):24–33, January 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Baquero Fernando and Negri María-Cristina. Challenges: Selective compartments for resistant microorganisms in antibiotic gradients. BioEssays, 19(8):731–736, August 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Hallatschek Oskar. Bacteria Evolve to Go Against the Grain. Physics, 5:93, August 2012. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Greulich Philip, Waclaw Bartłomiej, and Allen Rosalind J.. Mutational Pathway Determines Whether Drug Gradients Accelerate Evolution of Drug-Resistant Cells. Physical Review Letters, 109(8):088101, August 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Hermsen Rutger, Deris J. Barrett, and Hwa Terence. On the rapidity of antibiotic resistance evolution facilitated by a concentration gradient. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109(27):10775–10780, July 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Zhang Q., Lambert G., Liao D., Kim H., Robin K., Tung C. K., Pourmand N., and Austin R. H.. Acceleration of emergence of bacterial antibiotic resistance in connected microenvironments. Science, 333(6050):1764–7, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Zhang Qiucen Lambert, Guillaume Liao, Kim, Hyunsung Robin, Tung Kristelle, Chih-kuan Pourmand, Austin Nader, Robert H eng U54CA143803/CA/NCI NIH HHS/Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, Non-P.H.S. 2011/09/24 Science. 2011. Sep 23;333(6050):1764–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1208747. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Nagy Krisztina, Dukic Barbara, Hodula Orsolya, Ábrahám Ágnes, Csákvári Eszter, Dér László, Wetherington Miles T., Noorlag Janneke, Keymer Juan E., and Galajda Péter. Emergence of Resistant Escherichia coli Mutants in Microfluidic On-Chip Antibiotic Gradients. Frontiers in Microbiology, 13:820738, March 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Barrangou Rodolphe, Fremaux Christophe, Deveau Hélène, Richards Melissa, Boyaval Patrick, Moineau Sylvain, Romero Dennis A., and Horvath Philippe. CRISPR Provides Acquired Resistance Against Viruses in Prokaryotes. Science, 315(5819):1709–1712, March 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Marraffini Luciano A.. CRISPR-Cas immunity in prokaryotes. Nature, 526(7571):55–61, October 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Pul Ümit, Wurm Reinhild, Arslan Zihni, Geißen René, Hofmann Nina, and Wagner Rolf. Identification and characterization of E. coli CRISPR-cas promoters and their silencing by H-NS. Molecular Microbiology, 75(6):1495–1512, March 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Westra Edze R., Pul Ümit, Heidrich Nadja, Jore Matthijs M., Lundgren Magnus, Stratmann Thomas, Wurm Reinhild, Raine Amanda, Mescher Melina, Luc Van Heereveld Marieke Mastop, Gerhart E. Wagner H., Schnetz Karin, Van Der Oost John, Wagner Rolf, and Stan J. J. Brouns. H-NS-mediated repression of CRISPR-based immunity in Escherichia coli K12 can be relieved by the transcription activator LeuO. Molecular Microbiology, 77(6):1380–1393, September 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Pougach Ksenia, Semenova Ekaterina, Bogdanova Ekaterina, Datsenko Kirill A., Djordjevic Marko, Wanner Barry L., and Severinov Konstantin. Transcription, processing and function of CRISPR cassettes in Escherichia coli. Molecular Microbiology, 77(6):1367–1379, September 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Mojica Francisco J. M. and Díez-Villaseñor César. The on–off switch of CRISPR immunity against phages in Escherichia coli. Molecular Microbiology, 77(6):1341–1345, September 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Díez-Villaseñor C., Almendros C., García-Martínez J., and Mojica F. J. M.. Diversity of CRISPR loci in Escherichia coli. Microbiology, 156(5):1351–1361, May 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Perry E. B., Barrick J. E., and Bohannan B. J. M.. The molecular and genetic basis of repeatable coevolution between escherichia coli and bacteriophage t3 in a laboratory microcosm. Plos One, 10(6), 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Phan Trung V, Morris Ryan, Black Matthew E, Do Tuan K, Lin Ke-Chih, Nagy Krisztina, Sturm James C, Bos Julia, and Austin Robert H. Bacterial route finding and collective escape in mazes and fractals. Physical Review X, 10(3):031017, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Phan Trung V, Wang Gao, Do Tuan K, Kevrekidis Ioannis G, Amend Sarah, Hammarlund Emma, Pienta Ken, Brown Joel, Liu Liyu, and Austin Robert H. It doesn’t always pay to be fit: success landscapes. Journal of Biological Physics, 47:387–400, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Nagy Krisztina, Ágnes Ábrahám, Keymer Juan E., and Galajda Péter. Application of Microfluidics in Experimental Ecology: The Importance of Being Spatial. Frontiers in Microbiology, 9:496, March 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Attrill Erin L., Claydon Rory, Łapińska Urszula, Recker Mario, Meaden Sean, Brown Aidan T., Westra Edze R., Harding Sarah V., and Pagliara Stefano. Individual bacteria in structured environments rely on phenotypic resistance to phage. PLOS Biology, 19(10):e3001406, October 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].DeWitt Susanne K and Adelberg Edward A. THE OCCURRENCE OF A GENETIC TRANSPOSITION IN A STRAIN OF ESCHERICHIA COLI. Genetics, 47(5):577–585, May 1962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Pilizota Teuta and Shaevitz Joshua W.. Fast, Multiphase Volume Adaptation to Hyperosmotic Shock by Escherichia coli. PLoS ONE, 7(4):e35205, April 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Lederberg Joshua and Lederberg Esther M.. REPLICA PLATING AND INDIRECT SELECTION OF BACTERIAL MUTANTS. Journal of Bacteriology, 63(3):399–406, March 1952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Williams A. B.. Spontaneous mutation rates come into focus in. DNA Repair, 24:73–79, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Filloux Alain and Ramos Juan-Luis, editors. Pseudomonas Methods and Protocols, volume 1149 of Methods in Molecular Biology. Springer New York, New York, NY, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Polson A. and Shepard C.C.. On the diffusion rates of bacteriophages. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta, 3:137–145, January 1949. [Google Scholar]

- [38].Ghaeli Ima, Hosseinidoust Zeinab, Zolfagharnasab Hooshiar, and Monteiro Fernando Jorge. A New Label-Free Technique for Analysing Evaporation Induced Self-Assembly of Viral Nanoparticles Based on Enhanced Dark-Field Optical Imaging. Nanomaterials, 8(1):1, December 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Yosef I., Goren M. G., Kiro R., Edgar R., and Qimron U.. High-temperature protein g is essential for activity of the escherichia coli clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (crispr)/cas system. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 108(50):20136–20141, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Wingett Steven W. and Andrews Simon. FastQ Screen: A tool for multi-genome mapping and quality control. F1000Research, 7:1338, September 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Wick Ryan R., Judd Louise M., Gorrie Claire L., and Holt Kathryn E.. Unicycler: Resolving bacterial genome assemblies from short and long sequencing reads. PLOS Computational Biology, 13(6):e1005595, June 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Seemann T.. Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics, 30(14):2068–2069, July 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Lundgren A. and Kanewala U.. Experiences of testing bioinformatics programs for detecting subtle faults. Proceedings of 2016 Ieee/Acm International Workshop on Software Engineering for Science (Se4science), pages 16–22, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- [44].Bushnell B., Rood J., and Singer E.. Bbmerge - accurate paired shotgun read merging via overlap. Plos One, 12(10), 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Page Andrew J., Cummins Carla A., Hunt Martin, Wong Vanessa K., Reuter Sandra, Holden Matthew T.G., Fookes Maria, Falush Daniel, Keane Jacqueline A., and Parkhill Julian. Roary: rapid large-scale prokaryote pan genome analysis. Bioinformatics, 31(22):3691–3693, November 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Deatherage Daniel E. and Barrick Jeffrey E.. Identification of Mutations in Laboratory-Evolved Microbes from Next-Generation Sequencing Data Using breseq. In Sun Lianhong and Shou Wenying, editors, Engineering and Analyzing Multicellular Systems, volume 1151, pages 165–188. Springer New York, New York, NY, 2014. Series Title: Methods in Molecular Biology. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Phan Trung V, Mattingly Henry H, Vo Lam, Marvin Jonathan S, Looger Loren L, and Emonet Thierry. Direct measurement of dynamic attractant gradients reveals breakdown of the patlak-keller-segel chemotaxis model. bioRxiv, pages 2023–06, 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Wang M. Z., Zhu H., Wei J. Y., Jiang L., Jiang L., Liu Z. Y., Li R. C., and Wang Z. Q.. Uncovering the determinants of model escherichia coli strain c600 susceptibility and resistance to lytic t4-like and t7-like phage. Virus Research, 325, 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Washizaki Ayaka, Yonesaki Tetsuro, and Otsuka Yuichi. Characterization of the interactions between Escherichia coli receptors, LPS and OmpC, and bacteriophage T4 long tail fibers. MicrobiologyOpen, 5(6):1003–1015, December 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Yu F and Mizushima S. Roles of lipopolysaccharide and outer membrane protein OmpC of Escherichia coli K-12 in the receptor function for bacteriophage T4. Journal of Bacteriology, 151(2):718–722, August 1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Parker C T, Kloser A W, Schnaitman C A, Stein M A, Gottesman S, and Gibson B W. Role of the rfaG and rfaP genes in determining the lipopolysaccharide core structure and cell surface properties of Escherichia coli K-12. Journal of Bacteriology, 174(8):2525–2538, April 1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Louros N. N., Bolas G. M. P., Tsiolaki P. L., Hamodrakas S. J., and Iconomidou V. A.. Intrinsic aggregation propensity of the csgb nucleator protein is crucial for curli fiber formation. J Struct Biol, 195(2):179–189, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Sato T., Takano A., Hori N., Izawa T., Eda T., Sato K., Umekawa M., Miyagawa H., Matsumoto K., Muramatsu-Fujishiro A., Matsumoto K., Matsuoka S., and Hara H.. Role of the inner-membrane histidine kinase rcsc and outer-membrane lipoprotein rcsf in the activation of the rcs phosphorelay signal transduction system in escherichia coli. Microbiology (Reading), 163(7):1071–1080, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Vidakovic Lucia, Singh Praveen K., Hartmann Raimo, Nadell Carey D., and Drescher Knut. Dynamic biofilm architecture confers individual and collective mechanisms of viral protection. Nature Microbiology, 3(1):26–31, October 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Wielgoss Sébastien, Bergmiller Tobias, Bischofberger Anna M., and Hall Alex R.. Adaptation to Parasites and Costs of Parasite Resistance in Mutator and Nonmutator Bacteria. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 33(3):770–782, March 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Pribis J. P., Zhai Y., Hastings P. J., and Rosenberg S. M.. Stress-induced mutagenesis, gambler cells, and stealth targeting antibiotic-induced evolution. mBio, 13(3):e0107422, 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Leclerc Q. J., Lindsay J. A., and Knight G. M.. Modelling the synergistic effect of bacteriophage and antibiotics on bacteria: Killers and drivers of resistance evolution. Plos Computational Biology, 18(11), 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Mizoguchi Katsunori, Morita Masatomo, Fischer Curt R., Yoichi Masatoshi, Tanji Yasunori, and Unno Hajime. Coevolution of Bacteriophage PP01 and Escherichia coli O157:H7 in Continuous Culture. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 69(1):170–176, January 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Bohannan B.J.M. and Lenski R.E.. Linking genetic change to community evolution: insights from studies of bacteria and bacteriophage. Ecology Letters, 3(4):362–377, July 2000. [Google Scholar]

- [60].Fijalkowska I. J., Schaaper R. M., and Jonczyk P.. Dna replication fidelity in escherichia coli: a multi-dna polymerase affair. Fems Microbiology Reviews, 36(6):1105–1121, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Shee C., Ponder R., Gibson J. L., and Rosenberg S. M.. What limits the efficiency of double-strand break-dependent stress-induced mutation in escherichia coli? Journal of Molecular Microbiology and Biotechnology, 21(1–2):8–19, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Phan Trung V, Morris Ryan J, Lam Ho Tat, Hulamm Phuson, Black Matthew E, Bos Julia, and Austin Robert H. Emergence of escherichia coli critically buckled motile helices under stress. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(51):12979–12984, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Bos J., Zhang Q., Vyawahare S., Rogers E., Rosenberg S. M., and Austin R. H.. Emergence of antibiotic resistance from multinucleated bacterial filaments. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 112(1):178–83, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Lourenco M., Chaffringeon L., Lamy-Besnier Q., Titecat M., Pedron T., Sismeiro O., Legendre R., Varet H., Coppee J. Y., Berard M., De Sordi L., and Debarbieux L.. The gut environment regulates bacterial gene expression which modulates susceptibility to bacteriophage infection. Cell Host and Microbe, 30(4):556–+, 2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Clarke David J. The Rcs phosphorelay: more than just a two-component pathway. Future Microbiology, 5(8):1173–1184, August 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Ferrières Lionel and Clarke David J.. The RcsC sensor kinase is required for normal biofilm formation in Escherichia coli K-12 and controls the expression of a regulon in response to growth on a solid surface: E. coli Rcs regulon. Molecular Microbiology, 50(5):1665–1682, October 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Poranen M. M., Ravantti J. J., Grahn A. M., Gupta R., Auvinen P., and Bamford D. H.. Global changes in cellular gene expression during bacteriophage prd1 infection. J Virol, 80(16):8081–8, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Chanishvili N.. Phage therapy-history from twort and d’herelle through soviet experience to current approaches. Advances in Virus Research, Vol 83: Bacteriophages, Pt B, 83:3–40, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Turner P. E., Azeredo J., Buurman E. T., Green S., Haaber J. K., Haggstrom D., Carvalho K. K. D., Kirchhelle C., Moreno M. G., Pirnay J. P., and Portillo M. A.. Addressing the research and development gaps in modern phage therapy. Phage-Therapy Applications and Research, 5(1):30–39, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- [70].Gómez Pedro and Buckling Angus. Bacteria-Phage Antagonistic Coevolution in Soil. Science, 332(6025):106–109, April 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Valappil Sarshad Koderi, Shetty Prateek, Deim Zoltán, Terhes Gabriella, Urbán Edit, Váczi Sándor, Patai Roland, Polgár Tamás, Pertics Botond Zsombor, Schneider György, Kovács Tamás, and Rákhely Gábor. Survival Comes at a Cost: A Coevolution of Phage and Its Host Leads to Phage Resistance and Antibiotic Sensitivity of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Multidrug Resistant Strains. Frontiers in Microbiology, 12:783722, December 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Diallo K. and Dublanchet A.. Benefits of combined phage-antibiotic therapy for the control of antibiotic-resistant bacteria: A literature review. Antibiotics-Basel, 11(7), 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data generated in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The raw sequences are available at the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA) database under the study number PRJEB73316.