Abstract

There are approximately 1.4 million young carers in the United States alone. Being a young carer can result in parentification, a type of role reversal that occurs when children take on the roles and responsibilities of the adult. The purpose of this concept analysis is to provide a better understanding of the phenomenon of parentification among young carers through a description of its antecedents, attributes, and consequences using the steps of Rodgers’ evolutionary method. The databases CINAHL, PubMed, PsycINFO, and Scopus were searched to identify 25 articles. The antecedents of the concept include the dependency of the care receiver and the child’s adoption of a caregiving role. The attributes include fairness, obligation, resiliency, individuation, confidence in performing care tasks, cultural normalcy, family system functioning, support system, family resources, caregiver-care receiver relationship, and awareness of the child’s needs. Parentification has both positive and negative consequences that impact the young carer. The antecedents, consequences, and identifiable attributes of the concept are presented through this work to provide a comprehensive picture of parentification among young carers. These findings showcase the multidimensional nature of parentification and the broad impact that it can have on young carers. While these findings do provide greater insight into young carers, the fact remains that little is known about this underserved and underacknowledged population. This concept analysis provides a foundation of understanding that specifies potential targets for intervention development, as well as modifiable outcomes, that can be explored through future research and intervention work.

Keywords: Young carers, Caregiving children, Parentification, Concept analysis

In the United States alone, approximately 53 million individuals (aged 18 and older) act as a caregiver (AARP & National Alliance for Caregiving, 2020). Caregiving is typically shared among primary and secondary caregivers, where the primary caregiver is the person providing most of the assistance (Barbosa et al., 2011). However, important contributors to this caregiving system, children aged younger than 18, are often overlooked. It is estimated that in the United States there are approximately 1.4 million young carers (aged 8–18) (National Alliance for Caregiving, 2005, March). This number is based on the only national survey conducted in this population in 2005 and is understood to be a vast underestimation because often neither these children nor the individuals they are helping care for (a) know they are acting as a caregiver or (b) want to acknowledge that they are (National Alliance for Caregiving, 2005). As caregivers, children often provide multifaceted, extended care as a secondary caregiver without any lessening of family, home, or school/work-related responsibilities (McGuire et al., 2012). In time, caregiving can become a role that requires more than a child can provide, both emotionally and physically (Hooper & Doehler, 2012).

Being a young carer can become traumatic and harmful when it is long-term and excessive, with responsibilities that exceed the capabilities of a child’s age or maturity level. (Boumans & Dorant, 2018, p. 2). This can result in parentification, the alteration or removal of boundaries within family structures that occurs when children take on the roles and responsibilities of the adult (Hooper & Doehler, 2012). These boundaries represent the implied and obvious rules and expectations that exist within familial relationships (Earley & Cushway, 2002).

While there is an acknowledgement within the literature of the consequences of caregiving among children, the literature rarely addresses (a) how these consequences may be related to parentification and (b) what the resulting consequences of parentification can be for these children. The term parentification has its origins in sociology/psychology and over the years its usage has expanded to include children taking on adult roles and responsibilities in instances of not just parental neglect, but also in instances of parental illness or incapacitation (Earley & Cushway, 2002; Khafi et al., 2014). It has also been determined that parentification is a multidimensional concept unique to the individual experiencing the phenomenon, as well as to the context they find themselves in, resulting in both positive and negative outcomes (Khafi et al., 2014; McMahon & Luthar, 2007; Williams & Francis, 2010). Research pertaining to parentification among young carers is limited as this is a relatively new area of research and because the population of young carers is difficult to reach (Keenan et al., 2007). The aim of this concept analysis is to use Rodgers evolutionary concept analysis method to describe the antecedents, attributes, and consequences of parentification among young carers. The long-term intention is to use findings from this analysis to form a foundation for future research and intervention development and to allow future refinement of this concept as new research arises.

Methods

The Rodgers’ method was selected to conduct this concept analysis because of (a) its focus on “relevant purpose” (b) its use of the inductive method, (c) its goal in directing research, and (d) its belief that concepts are influenced by context and are thus continually evolving over time (McEwen & Wills, 2014; Rodgers & Knafl, 2003; Tofthagen & Fagerstrom, 2010). An induction was made regarding the components of the concept of parentification among young carers through thorough review and analysis of the literature, using the steps of the Rodgers’ method. These steps include: (1) identifying the concept and its associated terms, (2) determining the setting and sample for data collection, (3) collecting relevant data via systematic review of the literature, (4) analyzing the collected data to identify the attributes and the contextual basis (antecedents and consequences) of the concept, (5) identifying an exemplar, if needed, and (6) defining implications and hypotheses for future research and development (McEwen & Wills, 2014, p. 60). Antecedents refer to the situations or events which must occur before the concept can occur, attributes are the characteristics of a concept that make its identification possible, and consequences occur after the concept occurs or as a result of the concept (Rodgers & Knafl, 2003; Tofthagen & Fagerstrom, 2010).

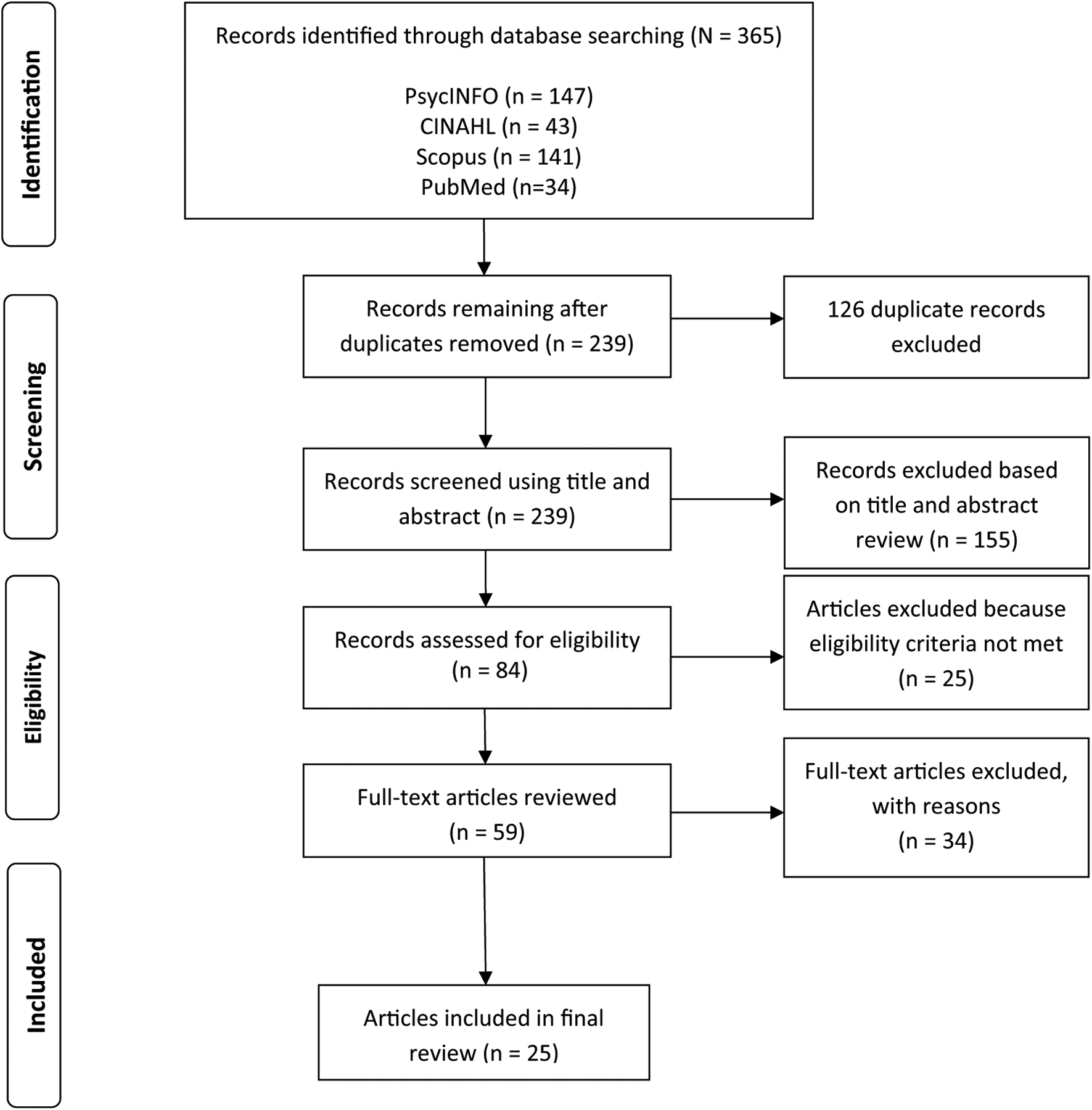

The literature search was conducted by the primary author using the databases PsycINFO, CINAHL, Scopus, and PubMed. The search terms were ((“parentification” OR “role reversal”) AND (“caregiv*” OR illness OR cancer OR disease)) and were based on the interchangeability of the terms parentification and role reversal in the literature. In addition, the term caregiving/caregiver is not always used, so the terms illness, cancer, and disease were added to account for this variability. Article inclusion criteria included: being written in English, having full text availability, and being published in the last 25 years (1994–2019). The search yielded 365 articles. After 126 duplicates were removed, 239 articles remained. A review of titles and abstracts was then conducted. Study inclusion criteria: (1) primary research addressing parentification or role reversal in a child, and (2) related to caregiving due to familial illness, disease, or cancer. Exclusion criteria included studies that addressed parentification in settings not related to familial illness or in situations where the child was not the main subject of the discussion on parentification. Non-primary studies including reviews, instrument development papers, and dissertations were also not included. The search results were reviewed by one of the authors (M.A.B.) An illustration of this process is included in Fig. 1 as a PRISMA diagram.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA diagram of literature search method

Results

The search yielded 25 studies which varied by method (19 quantitative, five qualitative, one mixed method) and country of origin (U.S.A., Zimbabwe, The Netherlands, United Kingdom, Canada, South Africa, Belgium, and Italy) (See Table 1). These studies were reviewed to identify the antecedents, attributes, and consequences of the concept of parentification among young carers. The results of the analysis conducted using the steps of Rodgers method are organized as follows: antecedents, attributes, consequences (positive and negative).

Table 1.

Literature search results for parentification among young carers

| Sample | Study aim (s) | Design, setting, context | Definition of parentification given | Parentification measure utilized | Relationship to framework | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Abraham & Stein, 2013) | N = 52 Mean age 19.8 ± 2.3, Female: 81% |

(1) To examine whether emerging adults’ affection, reciprocity, felt obligation and role reversal in their relationship with their mother mediate the association between their mother’s mental illness and their own psychological symptoms | Design: Quantitative Setting: U.S.A Context: Mental Illness |

Parentification: “role reversal characterized by a one-sided nature of exchange where children or adolescents assume the role of parenting their parents” | The Relationship with Parents Scale | – |

| (Boumans & Dorant, 2018) | N = 56 Mean age: 19.2 ± 1.9 Female: 76.8% |

(1) To explore young adult carers’ perceptions of parentification, resilience, and coping compared to young adult noncarers | Design: Quantitative Setting: Netherlands Context: Chronic Medical Condition |

Parentification: “a reversal of roles within the family system, whereby the child is acting as a parent or as a ‘mate’ to its parent” | Maastricht Parentification Scale | Attributes: Support system, Family resources Consequences: Autonomy, Coping skills |

| (Bauman et al., 2006) | N = 50 Aged 8–16 U.S.A.: Female: 64% Zimbabwe: Female: 58% |

(1)To document the degree to which children of parents with HIV/AIDS take on adult responsibilities and the kinds of responsibilities they have (2)To document their psychological status |

Design: Quantitative Setting: U.S.A. & Zimbabwe Context: HIV/AIDS |

Parentification: “children assume responsibilities performed more appropriately by an adult” | Parentification Scale (Mika et al., 1987) Emotional Parentification Questionnaire | – |

| (Dearden & Becker, 2000) | N = 60 Aged 16–25 Gender Not Reported |

(1) To investigate the extent to which caring influenced young people’s decisions and activities in relation to education, training and employment, leaving home and becoming an adult | Design: Qualitative Setting: United Kingdom Context: Long term illness or disability |

Parentification: definition not provided | N/A | Consequences: School, Internalizing Problems, Maturity, Responsibility |

| (Fagan, 2003) | N = 25; mothers with children aged 3–17 Child Gender Not Reported |

(1) To investigate the relationship between mothers’ migraines and the roles and expectations of their children | Design: Quantitative Setting: Canada Context: Migraine |

Parentification: “children assuming adult roles inappropriately or prematurely before they are emotionally or developmentally able to manage these roles successfully” | Adult-Adolescent Parenting Inventory | Attributes: confidence in performing care tasks |

| (Hooper et al., 2012) | N = 51 Mean age: 13.8 ± 1.3 Female: 51% |

(1) To explore the link between family factors, parent health, and adolescent health | Design: Quantitative Setting: U.S.A Context: Not Specified |

Parentification: “a process, whereby parental roles and responsibilities are abdicated by parents and carried out by children and adolescents.” | Parentification Questionnaire—Youth (PQ-Y) | Consequences: internalizing problems |

| (Hooper & Doehler, 2012) | N = 787 Mean age: 20.86 ± 3.5 Female: 76% |

(1) To report on the relations between retrospective childhood parentification and adult functioning—both psychological health and physical health— which may engender confidence in their use among therapists in the clinical and practice community | Design: Quantitative Setting: U.S.A Context: Not Specified |

Parentification: “a disturbance in generational boundaries that can be evidenced by a reversal of roles within the family system” |

Parentification

Questionnaire Parentification Scale Parentification Inventory |

Attributes: confidence in performing care tasks, support system, awareness of child’s needs Consequences: Stress, self-concept |

| (Hooper et al., 2008) | N = 156 Mean age = 22 Female: 70% |

(1) To examine how bimodal growth and distress consequences might be predicted by childhood parentification | Design: Quantitative Setting: U.S.A Context: Not Specified |

Parentification: “role reversal wherein a child becomes responsible for a parent’s and/or other family members’ emotional or behavioral needs” | Parentification Questionnaire-Adult | Attributes: resiliency, individuation |

| (Jones & Wells, 1996) | N = 360 Mean age: 21 Female: 67% |

(1) To examine the relationship between parentification and predicted characterological adaptations | Design: Quantitative Setting: U.S.A Context: Not Specified |

Parentification: “the expectation that a child will assume a caretaking role for the parent(s)” | Parentification Questionnaire-Adult | Consequences: compulsive caretaking |

| (Jurkovic et al., 2001) | N = 382 (assigned to confirmatory (C) or exploratory (E) group) Mean age C: 23.1 Mean age E: 23.2 |

(1) To compare the responses of late adolescent and young adult children on a new multidimensional measure of parentification assessing the extent and fairness of past and present caregiving | Design: Quantitative Setting: U.S.A Context: Not Specified |

Parentification: definition not provided | Parentification Questionnaire-Adult | Attributes: perception of fairness |

| (Keigher et al., 2005) | N = 7 Female: 100% |

(1) To examine issues facing young caregivers by analyzing narratives of the everyday lived reality of their mothers who have HIV | Design: Qualitative Setting: U.S.A Context: HIV/AIDS |

Parentified child: “child acts as a caretaking parent to his/her own parent” | N/A | – |

| (Kelley et al., 2007) | N = 368 Mean age = 21 Female: 100% |

(1) To examine parentification and family responsibility between families with alcoholism and those without | Design: Quantitative Setting: U.S.A Context: Alcoholism |

Pareiitification: “children or adolescents assume adult roles before they are emotionally or developmentally ready” | Parentification Questionnaire-Adult | Attributes: awareness of child’s needs Consequences: poor peer relationships |

| (Khafi et al., 2014) | N = 143 T1 Mean age = 10 years, T2 Mean age = 15 Male 48% Female 52% |

(1) To describe patterns of emotional and instrumental parentification from early to late adolescence (2) to assess the impact of parentification on youth’s adjustment (3) to assess the moderating role of ethnicity on relations between parentification and adjustment |

Design: Quantitative Setting: U.S.A Context: anxiety, affective, and/or substance use disorders |

Parentification: “an outgrowth of a family process wherein children provide emotional and/or instrumental care for their parents” | Child Caretaking Scale | Attributes: Relationship between young carer and care receiver, family resources Consequences: Internalizing problems, maturity, responsibility |

| (Laghi et al., 2018) | N = 86 Mean age: 16.74 ± 3.8 Gender Not Reported |

(1) To investigate how family functioning, the degree to which family members feel happy and fulfilled with each other, and the demographical characteristics of siblings impacted on sibling relationships | Design: Quantitative Setting: Italy Context: Autism | Parentification: “a phenomenon in which tasks typically reserved for parents or adults are completed by daughters and sons” | N/A | Attributes: confidence in performing care tasks, family system functioning |

| (Lane et al., 2015) | N = 349 Mean age: 13.4 ± 2.3 Female: 60.7% |

(1) To explore the nature of responsibility among children affected by illness in deprived South African communities | Design: Mixed Methods Setting: South Africa Context: Not Specified |

Parentification: definition not provided | N/A | – |

| (McMahon & Luthar, 2007) | N = 361; Mean age = 12 Male 46% Female 54% |

(1) To examine the psychosocial correlates of caretaking burden within a sample of children living in high-risk family systems characterized by maternal psychopathology | Design: Quantitative Setting: U.S.A Context: Mental Illness |

Parentification:”a family process involving developmentally inappropriate expectations that children function in a parental role within stressed, disorganized family systems” | Child Caretaking Scale | Consequences: poorself-concept, school, compulsive caretaking, life skills |

| (Murphy et al., 2008) | N = 108 Aged 6–11 at time of recruitment |

(1) To investigate autonomy among early and middle adolescents affected by maternal HIV/AIDS | Design: Quantitative; Longitudinal Setting: U.S.A Context: HIV/AIDS |

Parentification: “refers to children who assume parental responsibility in the home.” | Early Responsibility-Taking Due to Maternal HIV | – |

| (Nuttall etal.,2018) | N = 108 Mean age: 20.37 ± 1.6 Female: 69.4% |

(1) To descriptively understand childhood experiences of parentification and future caregiving intentions (2) to understand the processes through which childhood experiences of parentification impact future intentions to provide caregiving |

Design: Quantitative Setting: U.S.A Context: Autism |

Parentification: “high levels of caregiving behaviors” | Parentification Inventory | Attributes: awareness of child’s needs, relationship between young carer and care receiver Consequences: compulsive caretaking |

| (Petrowski & Stein, 2016) | N = 10 Aged 18–22 Female: 100% |

(1) To examine young adults’ accounts of ways that maternal mental illness has impacted their lives | Design: Qualitative Setting: U.S.A Context: Mental Illness |

Parentification: “a onesided exchange in family roles where children or adolescents assume a caregiver or parenting role for their parents and/or siblings” | N/A | Attributes: Relationship between young carer and care receiver, felt obligation Consequences: coping skills, life skills |

| (Stein et al., 1999) | N = 183 Mean age: 14.8 ± 2.1 Female: 54% |

(1) to assess the predictors and outcomes of parentification among adolescent children of parents with AIDs using a two-phase longitudinal study. Phase 1 assessed adolescent demographics and parentification. Phase 2 assessed outcome variables | Design: Quantitative; Longitudinal Setting: U.S.A Context: HIV/AIDS |

Parentification: “a situation in which children are prematurely forced into fulfilling parental roles and assuming adult responsibilities” | Parentification Scale | Attributes: Relationship between young carer and care receiver Consequences: Coping skills, empathy |

| (Thomas et al., 2003) | N = 21 Mean age: 14 Female: 61.9% |

(1) To learn about the characteristics of ‘young carers’, their experiences of life, their perspectives on their situation and role as ‘young carers’, and their hopes and expectations for the future | Design: Qualitative Setting: United Kingdom Context: Not Specified |

Parentification: “role reversal where children are seen as ‘parenting their parent”‘ | N/A | Attributes: felt obligation |

| (Tompkins, 2007) | N = 43 Aged 9–16 Gender Not Reported |

(1) To examine the relationship between parentification, parenting, and child adjustment among a) children whose mother was HIV infected and b) same age peers whose mothers were not infected | Design: Quantitative Setting: U.S.A Context: HIV/AIDS |

Parentification: “role reversal in which the child assumes some or all of the instrumental and expressive caretaking functions for the parent” | Parentification Scale | Consequences: school, peer relationships, age appropriate activities, life skills |

| (Van Loon et al., 2017) | N = 118 Aged 11–16 Male 49% Female 51% |

(1) To examine the effect of parentification on both internalizing and externalizing problems | Design: Quantitative; Longitudinal Setting: Netherlands Context: Mental Illness |

Parentification:”a type of role reversal, boundary distortion, and inverted hierarchy between parents and children in which they assume developmentally inappropriate levels of responsibility in the family” | Parentification Questionnaire-Youth | Consequences: Stress, internalizing problems |

| (Van Parys & Rober, 2014) | N = 14 Aged 7–14 Male (n = 5) Female (n = 9) |

(1) To determine how children, experience parental depression (2) To explore their caregiving experience in the family |

Design: Qualitative Setting: Belgium Context: Depression |

Parentification:”children feel the vulnerabilities in their parent and try to act in ways that cause the least trouble or try to actively contribute to the family’s well-being” | N/A | |

| (Williams & Francis, 2010) | N = 99 Mean age = 24 Male 17% Female 83% |

(1) To examine the role of the internal locus of control as a moderating variable between childhood parentification and adult psychological adjustment | Design: Quantitative Setting: Canada Context: Not Specified |

Parentification: “functional and/or emotional role reversal in which a child forfeits his or her own needs to become responsible for the emotional and/or behavioral needs of a parent” | The Parentification Questionnaire | Consequences: school, internalizing problems, coping skills |

Antecedents

The antecedent of parentification among young carers is the adoption of a caregiving role by a child due to the dependency of care receiver; wherein the child provides emotional and/or instrumental support that is typically provided by the adult (Boumans & Dorant, 2018; Hooper & Doehler, 2012; Khafi et al., 2014; Van Loon et al., 2017).

Attributes

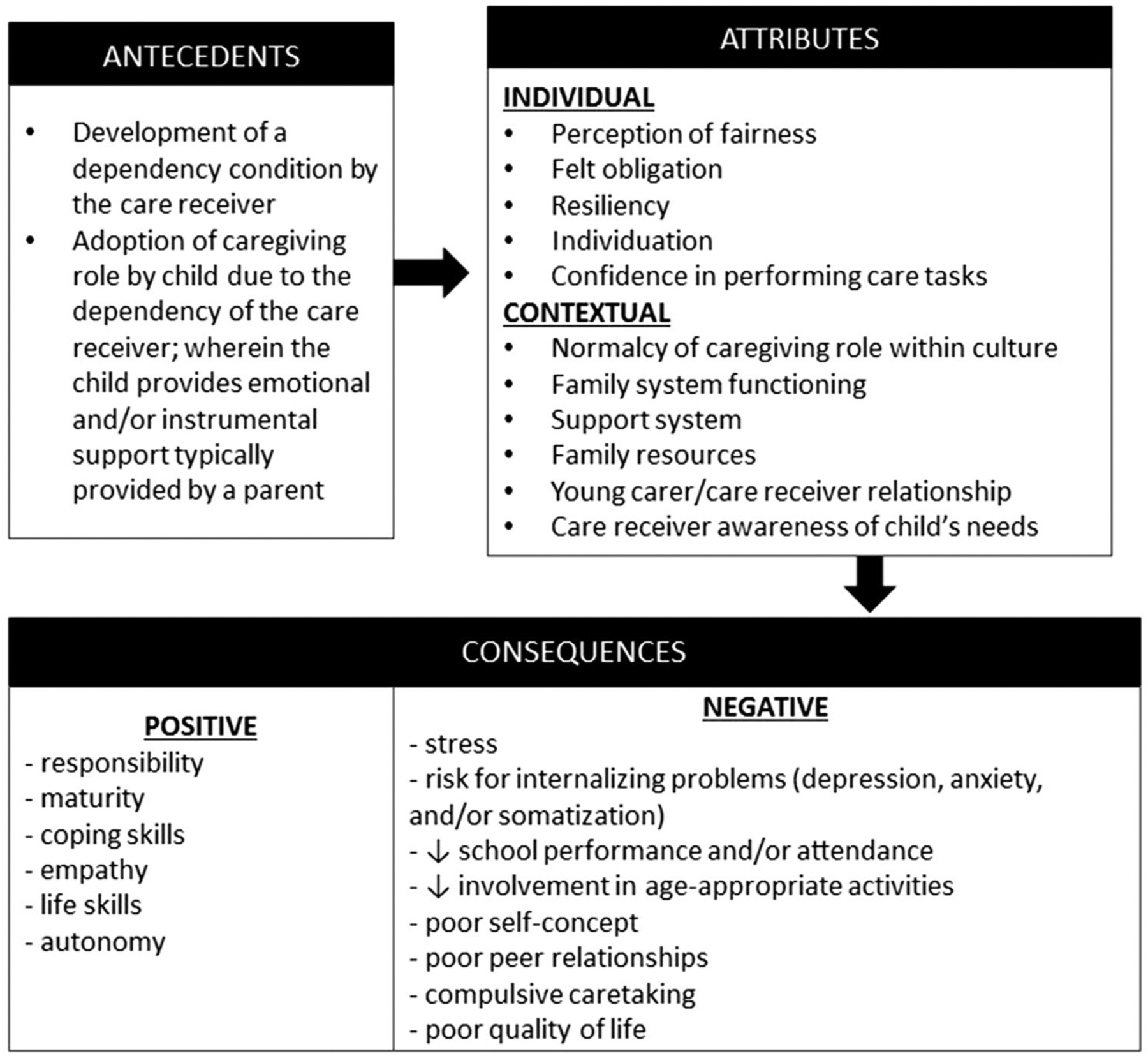

The attributes of parentification among young carers include perception of fairness, felt obligation, resiliency, individuation, confidence in performing care tasks, cultural normalcy of caregiving role, family system functioning, familial support, family resources, caregiver-care receiver relationship, and care receiver awareness of child’s needs (See Fig. 2). These are further divided into individual attributes, those related to the child themselves, and contextual attributes, those related to the context the child finds themselves in.

Fig. 2.

Conceptual model for parentification among young carers

Individual Attributes

Perceived fairness

Perceived fairness is the extent to which caregiving tasks are acknowledged, supported, and reciprocated (Jurkovic et al., 2001). When their caregiving role is not acknowledged and supported, young carers are more likely to perceive the role as unfair (Tompkins, 2007). Young carers are often caring for a parent or family member, and because of this relationship, they may feel it is required that they adopt a caregiving role. This is referred to as ‘felt obligation.’ Felt obligation encompasses the feelings of the child to provide obligatory assistance to the care receiver based on their relationship (Petrowski & Stein, 2016). Conversely, when a child does not feel that it is required that they adopt a caregiving role, and instead feels that they are voluntarily or willingly adopting the role, they may not experience felt obligation.

Resiliency

Resiliency is the ability of an individual to overcome challenges that may impact their development. In doing so, they are moving through the developmental stages towards adulthood (Hooper et al., 2008). For example, if children can negotiate the challenges resulting from caregiving, their development will not be impacted. When a child possesses resiliency, they are less likely to experience the negative outcomes that can result from parentification. Individuation occurs when an individual maintains their sense of self amid stressful environments and/or relationships (Hooper et al., 2008). One such stressful environment and/or relationship is that which is imposed upon young carers due to role reversal. If a child lacks individuation, they are more likely to be affected by the stressful experience of caregiving and therefore, more likely to experience negative outcomes.

Confidence in performing care

Confidence in performing care tasks can relate to the developmental appropriateness of the care task, the education provided related to the care task, the child’s age and/or maturity level, and their comfort related to performing their caregiving role (Fagan, 2003; Hooper & Doehler, 2012; Laghi et al., 2018). When a child lacks confidence in performing care tasks, they may be more likely to experience negative outcomes; whereas, a child who has confidence in performing care tasks, may be more likely to experience positive outcomes such as increased life skills, responsibility, and autonomy.

Contextual Attributes

Lack of normalcy of caregiving role

Lack of normalcy of caregiving role within culture is an attribute of parentification among young carers that is more likely to result in negative consequences. Within certain cultures, including many in Latin American, Asia, and Africa, caregiving is often viewed differently from the typical western or U.S. perspective (Khafi et al., 2014). For example, compared to those of European American descent, who typically focus on autonomy and independence, native Latin American, Asian, and African individuals tend to have an increased focus on family, duty, and responsibility (Khafi et al., 2014). When caregiving is seen through this perspective, negative effects of the role diminish (Gelman & Rhames, 2018; Khafi et al., 2014).

Poor family system functioning and lack of support

Poor family system functioning and lack of support within a family are both attributes of parentification among young carers that can result in more negative outcomes. A well-functioning family system involves cohesion, a family’s emotional bonding and flexibility, and the ability of the family to adapt to change (Laghi et al., 2018). When a family does not possess these characteristics, it is unable to provide support for its members, including young carers (Laghi et al., 2018). Another component related to lack of support within a family is its construction. In single parent households or households with multiple young children, there is an increase in the demands of the child as well as a lack of support (Boumans & Dorant, 2018; Hooper & Doehler, 2012; Khafi et al., 2014). Limited family resources stem from the socioeconomic status of the family. When a family has lower socioeconomic status, they are typically unable to hire additional caregivers and may require all members of the household to have a job out of necessity (Boumans & Dorant, 2018; Gelman & Rhames, 2018; Khafi et al., 2014). This lack of family resources can increase the burden of young carers and inhibit their ability to receive support. Therefore, limited family resources is also an attribute.

Awareness of child’s needs

Awareness of child’s needs occurs when the care receiver is able and willing to provide support to a young carer or when the care receiver prioritizes the needs of the child over their own (Hooper & Doehler, 2012; Kelley et al., 2007; Nuttall et al., 2018; Thastum et al., 2008). When there is a lack of this awareness of the child’s needs, negative outcomes are more likely to occur. Similarly, a poor relationship between the young carer and the care receiver, characterized by lack of communication and/or resentment, is also an attribute of parentification that may result in negative outcomes (Khafi et al., 2014; Nuttall et al., 2018; Petrowski & Stein, 2016). The relationship between the young carer and care receiver is also affected by the dependency of the care receiver on the young carer (Khafi et al., 2014; Stein et al., 1999). The dependency of the care receiver is contingent upon the type, severity, and onset of their illness. When their illness is more severe, more life-threatening, and/or more debilitating, there is an increase in their dependency on the young carer (Khafi et al., 2014; Stein et al., 1999). This dependency can negatively impact the relationship between the young carer and care receiver.

Consequences

The concept of parentification among young carers has both positive and negative consequences. The negative consequences include an increase in the young carer’s stress, compulsive caretaking, and risk for internalizing problems. The negative consequences also include a decrease in the young carer’s school performance/attendance, a decreased involvement in age appropriate activities, poor peer relationships, and poor self-concept (See Fig. 2). Due to the demands of their caregiving role, young carers are prone to have higher stress levels than their non-caregiving peers (Hooper & Doehler, 2012; Van Loon et al., 2017). Additionally, due to the child’s demanding role, they may be unable to develop lasting relationships with their peers. Consequentially, their involvement in age appropriate activities can become limited (Gelman & Rhames, 2018; Kelley et al., 2007; Thomas et al., 2003). Furthermore, young carers are likely to have problems with school performance and attendance due to the demands of their caregiving role (Dearden & Becker, 2000, March; McMahon & Luthar, 2007; Thomas et al., 2003; Williams & Francis, 2010). Parentification can place young carers at an increased risk for internalizing problems, including depression and anxiety (Dearden & Becker, 2000, March; Hooper et al., 2012; Khafi et al., 2014; Van Loon et al., 2017; Williams & Francis, 2010). As a result of parentification, young carers may also develop a lack of sense of self (poor self-concept) (Hooper & Doehler, 2012; McMahon & Luthar, 2007). Their sense of self can become tied to their caregiving role in such a way that they become compulsive caretakers. As compulsive caretakers they may seek a caregiving role in future relationships, even when unnecessary (Jones & Wells, 1996; McMahon & Luthar, 2007; Nuttall et al., 2018).

The positive consequences of the concept include an increase in the young carer’s responsibility, maturity, coping skills, empathy, life skills, and autonomy (See Fig. 2). Due to the child’s involvement in care tasks, both instrumental and emotional, there is potential for the skills obtained to be used in the future (life skills) (McMahon & Luthar, 2007; Thomas et al., 2003). The young carers not only have ability to use these skills, but they also have the ability recognize when they need to be utilized (maturity and responsibility) (Dearden & Becker, 2000, March; Khafi et al., 2014). Because of parentification, a young carer can become more capable of making their own decisions (autonomy), and they can be better at dealing with difficult situations (coping skills) (Boumans & Dorant, 2018; Petrowski & Stein, 2016; Williams & Francis, 2010). Lastly, a young carer can have a greater ability of understanding the feelings and needs of others (empathy) (Petrowski & Stein, 2016).

Discussion

The findings of this analysis provide a greater understanding of the concept of parentification among young carers. The antecedents, consequences and identifiable attributes of the concept are presented to provide a comprehensive picture of this concept. These findings showcase the multidimensional nature of parentification and the broad impact that it can have on the lives of young carers. While these findings do provide greater insight into the population of young carers, the fact remains that very little is known about this vulnerable, underserved, and underacknowledged population. Young carers continue to adopt the caregiving role without the awareness, support, and education their older (aged > 18) caregiver counterparts receive. The current state of the science regarding the population of young carers is limited due to a lack of research, services, and policy. It is suggested that this paucity is due to the fact that child caregiving “transgresses societal expectations” of children (Smyth et al., 2011, p. 153). Simply put, society views children as receivers of care and consequentially has a difficult time accepting children in a caregiving role. Because of this, the awareness of the population of young carers is low, as is the awareness of the unique consequences young carers face, such as parentification (Smyth et al., 2011).

To illustrate this lack of research and awareness of the population of young carers, a global review was conducted by Leu and Becker in (2017). This review determined the level of awareness and response to young carers for each country either: (1) incorporated/sustained, (2) advanced, (3) intermediate, (4) preliminary, (5) emerging, (6) awakening, or (7) no response (Leu & Becker, 2017). Eighteen countries were ranked from 1 to 6 and all other countries, at the time of the review, were given a rank of 7 (no response) (Leu & Becker, 2017). No country achieved the status of incorporated/sustained, and only the United Kingdom received an advanced ranking (Leu & Becker, 2017). Of the eighteen countries receiving a ranking, only seven received a rank higher than that of emerging status (United Kingdom, Australia, Norway, Sweden, Austria, Germany and New Zealand). The remaining 11 countries (Belgium, Ireland, Italy, Sub-Saharan Africa, Switzerland, The Netherlands, United States, Greece, Finland, United Arab Emirates, and France) are therefore considered to have little public awareness about young carers, a limited research base, no specific legal rights for this population, and few, if any, dedicated services or interventions (Leu & Becker, 2017).

A strength of the framework of parentification among young carers resulting from this analysis is that it provides a foundation to be built upon through continued research. Studies focusing on parentification among young carers are severely limited, especially when reviewing existing literature pertaining to specific chronic illnesses or conditions. This framework, therefore, provides a foundation for the exploration of parentification in an area that is previously unstudied. Consequently, it has the potential to be expanded upon by researchers studying the phenomenon in illness specific contexts. Another strength of this framework is that it reflects research showing that parentification is not a purely pathological phenomenon. Much of the research related to parentification prior to the early 2000s examined only the negative consequences of parentification (Hooper et al., 2008). As a result, researchers viewed parentification as a detrimental experience and sought to determine ways in which to prevent parentification from occurring. This changed with more recent research exploring parentification as a phenomenon with bimodal outcomes (Hooper et al., 2008). These studies showcase the fact that role reversals, such as parentification, may result in positive consequences along with the expected negative consequences (Hooper et al., 2008; Tompkins, 2007). This framework illustrates both the potential positive and negative consequences of parentification among young carers, thus recent studies showing potential positive outcomes are incorporated. By acknowledging the bimodal outcomes of parentification, the framework provides a more comprehensive foundation for the continued exploration of the consequences experienced by young carers.

Implications and Conclusions

While research exists related to the antecedents and consequences of parentification, there is little research exploring how parentification can be prevented. Research needs to be conducted to determine how health care professionals and/or family members can identify children at risk of parentification and how they can help those at risk. Additionally, due to the differences in development stages within the population of young carers, further research needs to be conducted to determine if the consequences of parentification vary by developmental stage and if certain stages of development exhibit more parentification. Most of the research conducted in the population of young carers thus far is exploratory in nature. Future research should focus on the development of interventions aimed at mitigating the consequences of parentification and the subsequent efficacy of those interventions. In doing so, programs and services for young carers can be developed. Ultimately, the increase in research may lead to an increase in understanding and awareness of young carers and the unique challenges they face, such as parentification. This increase in awareness and understanding may lead to the development of programs and services for this population. In time, this combination of increased research and increased services may lead to the development of policy, which would result in even more research and services of the population of young carers. Therefore, future research exploring parentification among young carers will not only fill gaps related to parentification, but also gaps existing in the state of the science related to young carers.

The fact remains that little is known about young carers and the unique challenges they face. Parentification is a potential outcome they may experience due to their role as a caregiver. This concept analysis, conducted using the Rodgers’ method to outline the antecedents, attributes, and consequences of parentification among young carers, is a first step towards increasing our understanding of these children and their caregiving experiences. By refining this concept, it can lead to future research in this population, which can in time, fill the gaps, justify program and/or policy creation, and consequentially increase awareness of this understudied and underserved population.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval This chapter does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

References

- AARP & National Alliance for Caregiving. (2020). Caregiving in the United States 2020. AARP. 10.26419/ppi.00103.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abraham KM, & Stein CH (2013). When mom has a mental Illness: Role reversal and psychosocial adjustment among emerging adults. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 69(6), 600–615. 10.1002/jclp.21950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa A, Figueiredo D, Sousa L, & Demain S (2011). Coping with the caregiving role: Differences between primary and secondary caregivers of dependent elderly people. Aging & Mental Health, 15(4), 490–499. 10.1080/13607863.2010.543660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauman LJ, Foster G, Johnson Silver E, Berman R, Gamble I, & Muchaneta L (2006). Children caring for their ill parents with HIV/AIDS. Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies, 1(1), 56–70. 10.1080/17450120600659077 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boumans NPG, & Dorant E (2018). A cross-sectional study on experiences of young adult carers compared to young adult noncarers: Parentification, coping and resilience. Scandanavian Journal of Caring Science. 10.1111/scs.12586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dearden C, & Becker S (2000, March). Young carers’ transitions to adulthood. Childright. Retrieved from https://www.jrf.org.uk/report/young-carers-transitions-adulthood [Google Scholar]

- Earley L, & Cushway D (2002). The parentified child. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 7(2), 163–178. 10.1177/1359104502007002005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fagan MA (2003). Exploring the relationship between maternal migraine and child functioning. Headache, 43(10), 1042–1048. 10.1046/j.1526-4610.2003.03205.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelman CR, & Rhames K (2018). In their own words: The experience and needs of children in younger-onset Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias families. Dementia, 17(3), 337–358. 10.1177/1471301216647097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooper LM, & Doehler K (2012). Assessing family caregiving: A comparison of three retrospective parentification measures. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 38(4), 653–666. 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2011.00258.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooper LM, Doehler K, Jankowski PJ, & Tomek SE (2012). Patterns of self-reported alcohol use, depressive symptoms, and body mass index in a family sample: The buffering effects of parentification. The Family Journal, 20(2), 164–178. 10.1177/1066480711435320 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hooper LM, Marotta SA, & Lanthier RP (2008). Predictors of growth and distress following childhood parentification: A retrospective exploratory study. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 17(5), 693–705. 10.1007/s10826-007-9184-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jones RA, & Wells M (1996). An empirical study of parentification and personality. The American Journal of Family Therapy, 24(2), 145–152. 10.1080/01926189608251027 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jurkovic GJ, Thirkield A, & Morrell R (2001). Parentification of adult children of divorce: A multidimensional analysis. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 30(2), 245–257. 10.1023/A:1010349925974 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Keenan K, Miedzybrodzka Z, van Teijlingen E, McKee L, & Simpson SA (2007). Young people’s experiences of growing up in a family affected by Huntington’s disease. Clinical Genetics, 71(2), 120–129. 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2006.00702.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keigher S, Zabler B, Robinson N, Fernandez A, & Stevens PE (2005). Young caregivers of mothers with HIV: Need for supports. Children and Youth Services Review, 27(8), 881–904. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2004.12.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley ML, French A, Bountress K, Keefe HA, Schroeder V, Steer K, … Gumienny L (2007). Parentification and family responsibility in the family of origin of adult children of alcoholics. Addictive Behaviors, 32(4), 675–685. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.06.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khafi TY, Yates TM, & Luthar SS (2014). Ethnic differences in the developmental significance of parentification. Family Process, 53(2), 267–287. 10.1111/famp.12072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laghi F, Lonigro A, Pallini S, Bechini A, Gradilone A, Marziano G, & Baiocco R (2018). Sibling relationships and family functioning in siblings of early adolescents, adolescents and young adults with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 27(3), 793–801. 10.1007/s10826-017-0921-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lane T, Cluver L, & Operario D (2015). Young carers in South Africa: Tasks undertaken by children in households affected by HIV infection and other illness. Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies, 10(1), 55–66. 10.1080/17450128.2014.986252 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leu A, & Becker S (2017). A cross-national and comparative classification of in-country awareness and policy responses to ‘young carers.’ Journal of Youth Studies, 20(6), 750–762. 10.1080/13676261.2016.1260698 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen M, & Wills EM (2014). Theoretical basis for nursing (4th ed.). Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. [Google Scholar]

- McGuire DB, Grant M, & Park J (2012). Palliative care and end of life: The caregiver. Nursing Outlook, 60(6), 351–356.e20. 10.1016/j.outlook.2012.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon TJ, & Luthar SS (2007). Defining characteristics and potential consequences of caretaking burden among children living in urban poverty. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 77(2), 267–281. 10.1037/0002-9432.77.2.267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy DA, Greenwell L, Resell J, Brecht ML, & Schuster MA (2008). Early and middle adolescents’ autonomy development: Impact of maternal HIV/AIDS. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 13(2), 253–276. 10.1177/1359104507088346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Alliance for Caregiving. (2005, March). Young Caregivers in the U.S.: Report of Findings September 2005. Retrieved from https://www.caregiving.org/data/youngcaregivers.pdf

- Nuttall AK, Coberly B, & Diesel SJ (2018). Childhood caregiving roles, perceptions of benefits, and future caregiving intentions among typically developing adult siblings of individuals with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48(4), 1199–1209. 10.1007/s10803-018-3464-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrowski C, & Stein C (2016). Young women’s accounts of caregiving, family relationships, and personal growth when mother has mental illness. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25(9), 2873–2884. 10.1007/s10826-016-0441-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers BL, & Knafl KA (2003). Concept development in nursing : Foundations, techniques, and applications. Philadelphia: Saunders. [Google Scholar]

- Smyth C, Blaxland M, & Cass B (2011). ‘So that’s how I found out I was a young carer and that I actually had been a carer most of my life’. Identifying and supporting hidden young carers. Journal of Youth Studies, 14(2), 145–160. 10.1080/13676261.2010.506524 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stein JA, Riedel M, & Rotheram-Borus MJ (1999). Parentification and its impact on adolescent children of parents with AIDS. Family Process, 38(2), 193–208. 10.1111/j.1545-5300.1999.00193.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thastum M, Johansen MB, Gubba L, Olesen LB, & Romer G (2008). Coping, social relations, and communication: A qualitative exploratory study of children of parents with cancer. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 13(1), 123–138. 10.1177/1359104507086345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas N, Stainton T, Jackson S, Cheung WY, Doubtfire S, & Webb A (2003). Your friends don’t understand’: Invisibility and unmet need in the lives of ‘young carers. Child & Family Social Work, 8(1), 35–46. 10.1046/j.1365-2206.2003.00266.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tofthagen R, & Fagerstrom LM (2010). Rodgers’ evolutionary concept analysis: A valid method for developing knowledge in nursing science. Scandanavian Journal of Caring Science, 24, 21–31. 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2010.00845.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tompkins TL (2007). Parentification and maternal HIV infection: Beneficial role or pathological burden? Journal of Child and Family Studies, 16(1), 108–118. 10.1007/s10826-006-9072-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van Loon LM, Van de Ven MO, Van Doesum KT, Hosman CM, & Witteman CL (2017). Parentification, stress, and problem behavior of adolescents who have a parent with mental health problems. Family Process, 56(1), 141–153. 10.1111/famp.12165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Parys H, Smith JA, & Rober P (2014). Trying to comfort the parent: A qualitative study of children dealing with parental depression. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 39(3), 330–345. 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2012.00304.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams K, & Francis S (2010). Parentification and psychological adjustment: Locus of control as a moderating variable. Contemporary Family Therapy, 32(3), 231–237. 10.1007/s10591-010-9123-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]