Abstract

Background:

Many patients diagnosed with cancer use complementary and integrative healthcare (CIH) approaches to manage their cancer- and treatment-related symptoms and improve their well-being. Evidence suggests that counseling on CIH can improve health outcomes and decrease healthcare costs by increasing patient activation. This qualitative study explores the experiences of cancer patients who underwent interprofessional counseling on CIH to gain insights into how these patients were able to integrate recommended CIH measures into their daily lives while undergoing conventional cancer treatment.

Methods:

Forty semi-structured interviews were conducted with cancer patients participating in the CCC-Integrativ study and its process evaluation. The interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, and analyzed using content analysis following Kuckartz and Rädiker. A purposeful sampling strategy was used to achieve a balanced sample regarding gender, age, cancer diagnosis, and treatment approach.

Results:

Most patients with cancer reported largely implementing the CIH recommendations. Participants acknowledged the efficacy of CIH recommendations in managing their symptoms. They felt strengthened and empowered to actively take part in their healthcare decisions. However, the patients encountered obstacles in incorporating the recommended CIH applications into their daily routines. These challenges encompassed the effort required for treatment application (e.g., baths, compresses), limitations imposed by the cancer disease (e.g., fatigue, pain), difficulties acquiring necessary materials, associated costs, and lack of infrastructure for CIH. Facilitators of CIH implementation included the availability of easily manageable CIH measures (e.g., herbal teas), informative materials on their application, distribution of samples, family support, and a high level of self-efficacy. The patient-centered approach and strong patient-provider partnership within the counseling context were perceived as empowering. Participants expressed a desire for a consistent point of contact to address their CIH concerns.

Conclusions:

The findings underscore the benefits of CIH counseling for cancer patients’ symptom management and overall well-being. Healthcare professionals providing CIH counseling to patients with cancer may recognize the barriers identified to better support their patients in the regular use of CIH.

Keywords: complementary and integrative healthcare, integrative oncology, symptom control, cancer, qualitative analysis, interprofessional counselling, patient activation, patient counselling, self-management of healthcare decisions

Introduction

Complementary and integrative healthcare (CIH) is a commonly used approach among patients diagnosed with cancer.1,2 In countries with allopathic medicine dominance, healthcare practices beyond conventional care are labeled “complementary,” “alternative,” or “non-conventional.” 3 These include biological approaches like dietary supplements and phytotherapeutics, as well as non-drug therapies such as yoga, meditation, acupuncture, manual therapies, and spiritual therapies. In this article, the term “complementary and integrative healthcare” is employed to denote the integration of these methods with conventional therapies. 4

The reasons for cancer patients’ use of CIH are diverse, including the desire for improved symptom management and well-being, increased involvement in therapeutic decisions, and hope for cure.5 -7 Patients perceive CIH as a patient-centered approach that enables them to cope better with persistent health challenges due to practitioner empathy and empowerment. 8 A growing body of evidence indicates that specific CIH applications can positively impact treatment- and disease-related symptoms and health-related quality of life.9 -11 While CIH interventions may offer benefits in symptom management, there are also potential risks associated with their use. 12 Clinical guidelines recommend integrating evidence-based CIH information and treatments into standard cancer care to address patients’ informational needs and reduce the risks of seeking untrustworthy CIH services.13 -15 Integrating and discussing the use of CIH in cancer care can increase patient satisfaction, support the goal of providing patient-centered care through improved patient-physician communication, and enhance patient’s readiness to engage in shared healthcare decision-making.16 -18 As cancer treatments are often administered in an outpatient setting or during brief hospital stays, healthcare providers emphasize encouraging patients to actively participate in preventing or managing treatment- and disease-related symptoms.19 -21

To address this need, the CCC-Integrativ study, a complex interprofessional counseling intervention to enhance the integration of CIH into cancer care, was developed and evaluated at four comprehensive cancer centers (CCCs) in the South of Germany. 22 The study’s primary objective was to address cancer patients’ information needs regarding CIH and improve patient activation levels by offering three consultation sessions based on patients’ needs regarding CIH. 22 As the CCC-Integrativ study involved a complex multicenter intervention, a mixed methods process evaluation was conducted alongside the main study.23,24 Using qualitative research in conjunction with quantitative data can support developing and evaluating patient-centered interventions to tailor cancer care to individual patient experiences and needs. 25 The process evaluation aimed to identify the factors that influenced the implementation of the new CIH counseling approach and gain insight into intervention fidelity to develop strategies to optimize the intervention. 26 Three sub-studies were conducted to achieve this goal. 26

The present study focuses on the third sub-study of the process evaluation and reports on the qualitative analysis of the experiences and perceptions of cancer patients participating in the interprofessional CIH counseling program. Using a qualitative research approach, the present study aimed to examine to what extent patients with cancer incorporated the CIH recommendations they received during counseling into their daily lives. Moreover, the research objective was to explore which factors influence the implementation of these recommendations and participants’ perceived outcomes of the interprofessional CIH counseling program.

Methods

Study Design

The study was planned and executed following the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and the European Data Protection Law. The Medical Faculty of Heidelberg Ethics Committee granted ethical approval for the controlled study 22 and the process evaluation 26 (November 24th, 2020). A qualitative research approach was chosen to investigate the complex and subjective aspects of care and patients’ experiences with CIH counseling processes. Conducting in-depth interviews provided an opportunity to gain insight into the patients’ perspectives, their understanding of their illness and care, and how meaning is created and negotiated in the realm of CIH. 27

Data Collection

Data collection was conducted between July 2021 and April 2022 at the four participating CCCs. To maximize variance and ensure a comprehensive and diverse representation of patients’ experiences, 40 participants from the intervention group of the CCC-Integrativ study (details regarding the inclusion and exclusion criteria can be found in the main study protocol 22 ) were purposively sampled 28 based on their age, gender, treatment approach, and a wide range of cancer types. After evaluating the participants’ psychological, physical, and emotional well-being to ensure their participation was reasonable, the study’s aims and procedures were explained to the patients orally and in writing. The patients were given sufficient time (several days) to consider participation, after which written informed consent and a privacy policy agreement were obtained. Eighteen patients decided not to participate in the interview study due to psychological burdens, time issues, inpatient stays, or a deterioration in their health. However, purposeful sampling ensured that patients with similar characteristics, such as compromised health status and high symptom burden, were included in the study. The patient selection process continued until the desired sample size of 40 participants (10 per CCC) was achieved. Participants were informed about their right to withdraw consent without adverse effects on their medical care. After obtaining written consent, the first author, with a background in psychology and medicine, contacted the participants via phone or email to arrange interview sessions and to introduce herself and the study objectives.

Twenty interviews (five per CCC) took place following participants’ initial consultation (IC), and another 20 interviews (five per CCC) were conducted with participants who had received one or two follow-up consultations (FC). All interviews were carried out by the first author, either in-person at the CCCs (5%) or remotely via telephone (55%) or videoconference (40%), depending on the participant’s preference and mobility.

The in-depth interviews were conducted using a semi-structured interview guide that allowed for flexibility in adjusting the sequence of questions. The first two interviews served as a pilot test of the interview guide. Since the questions appeared comprehensible, only minor changes to the wording and sequence of questions had to be made, and the interviews were included in the overall analysis. The main topics of the interview guide included the participants’ previous experience with CIH approaches, their motivation to participate in the counseling program, their experience with the counseling sessions, and the interprofessional approach. Additionally, participants were asked about the implementation of the CIH recommendations into their daily routine, the supplemental information materials, their level of health literacy, and patient activation. The interview guide also covered the personal benefits of the counseling intervention, suggestions for improvement, and any potential unmet expectations. During the interviews, the interviewer sought to clarify details that emerged from the participants’ narratives by asking follow-up questions and providing prompts. Participants were given the opportunity to ask questions and share their experiences regarding the CIH counseling intervention, including both positive and negative aspects. A comprehensive description of the interview guide and its development was published elsewhere. 29

On average, the interviews lasted 44 minutes, ranging from 25 to 66 minutes. The spouse was present during the interview in two cases due to the participant’s speaking or hearing impairments; no repeated interviews were necessary. After each interview, the author documented additional field notes to capture significant aspects of the interview, the conversational tone, and any noteworthy features. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. All identifying information was removed from the transcripts to protect participants’ privacy.

Data saturation was reached after conducting 35 interviews with no new themes emerging. Due to logistical constraints, participants were not given the transcripts or findings to review and provide feedback or corrections.

Data Analysis

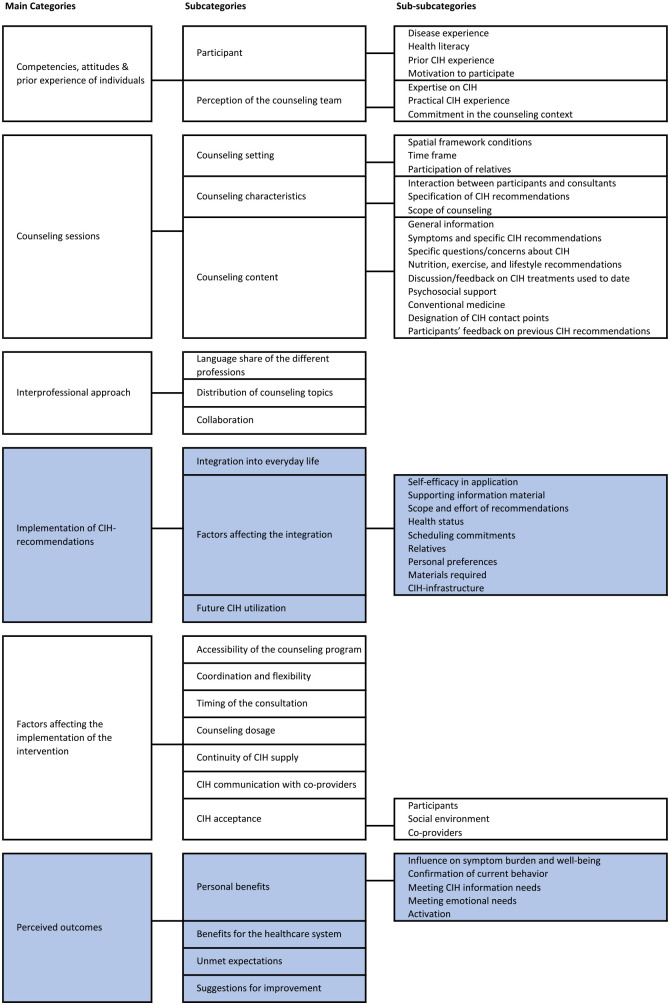

A deductive-inductive qualitative content analysis following the guidelines of Kuckartz and Rädiker 30 was applied for each interview. The qualitative data management software MAXQDA Analytics Pro 2022 31 was used to facilitate the coding and analysis of the pseudonymized transcripts. The first author familiarized herself with the material, incorporating the field notes, and developed an initial coding scheme. Codes and categories were developed deductively based on the topics of the interview guide and the research question and inductively from participants’ narratives. The coding scheme was refined through discussions with the multidisciplinary process evaluation team to improve the quality and validity of the analysis and to ensure intersubjectivity. The first and second authors independently coded 10% of the material using the adapted coding scheme, and the MAXQDA intercoder-agreement function was used to check for consistency between the coders at the segment level. The authors then discussed the discrepancies and refined the coding instructions to delineate the categories better. In the final step, the first author applied the refined coding scheme to code the entire dataset. Figure 1 presents the coding tree used to code the interviews. A detailed presentation of the codes and corresponding example citations for the categories and subcategories discussed in this article can be found in the appendix. To make the study’s results accessible to an international audience, the categories of the coding scheme and the participants’ quotes were translated from German into English. The quotes are reproduced below, along with the participants’ pseudonyms.

Figure 1.

Coding tree.

This article covers the categories, sub-categories and sub-subcategories highlighted in blue.

CIH, complementary and integrative healthcare

Reflexivity

To mitigate confirmation bias, individuals responsible for the process evaluation were not directly involved in implementing the counseling intervention. This separation aimed to maintain objectivity in evaluating the intervention. The first author, who was significantly engaged in data collection, processing, and analysis, is a medical doctoral student with a background in psychology. In preparation for the study, she participated in specialized workshops to gain expertise in qualitative research approaches. The other researchers involved in the process evaluation have diverse backgrounds (including general medicine, health services research, health sciences, nursing, and psychology) and possess extensive experience conducting mixed methods process evaluations related to CIH.32,33 Peer debriefings and discussions with the multidisciplinary research team enhanced the analysis process. These interactions provided opportunities for a thorough examination of the research outcomes and enhanced a comprehensive understanding of the data gathered from the interviews. Through these discussions, new perspectives and insights emerged, contributing to the empirical understanding of the factors influencing the implementation of CIH recommendations by cancer patients and their perceptions of the counseling program’s outcomes. This collaborative approach ensured a valid and reliable comprehension of the research findings.

Results

Participants’ Characteristics

Purposeful sampling resulted in a balanced sample (N = 40) in terms of gender (55.0% female, 45.0% male), age (mean age: 57 years, range: 24-84 years), and treatment approach (52.5% curative, 45.0% palliative, 2.5% unknown). There was high variability in the types of cancer represented in the sample, including 22.5% breast carcinoma, 12.5% prostate carcinoma, 10.0% colorectal carcinoma, 7.5% lung cancer, 7.5% biliary carcinoma, 7.5% hematological neoplasms, 7.5% gynecological tumors, and 25.0% other types of cancer. Most participants (n = 38) reported having prior experience with CIH treatments and expressed motivation to participate in the counseling program due to a desire for more information in this area. Further information on the competencies, attitudes, and prior experience of the individuals who participated in the counseling sessions, as well as participants’ perception of the counseling sessions, and the interprofessional approach, is presented elsewhere. 29

Implementation of the CIH-Recommendations

On average, participants received evidence-based recommendations for more than 10 CIH applications for symptom management during IC and FC. These treatments included non-pharmacological procedures such as acupressure, relaxation techniques, dietary modifications, and exercise; external applications like compresses, baths, and heat or cold therapy; and pharmacological procedures like phytotherapy, herbal teas, and other recommendations.

Integration into Everyday Life

The participants (n = 38) reported that they had implemented a significant portion of the CIH recommendations from the counseling sessions into their daily lives. However, two participants stated that they had received recommendations for preventive measures they could use if needed since they had no current complaints. These participants received curative therapy and reported no treatment- or cancer-related symptoms. One participant admitted that he had yet to use any CIH recommendations, citing insecurity due to conflicting recommendations made by other nutritionists and physicians.

Factors Affecting the Integration

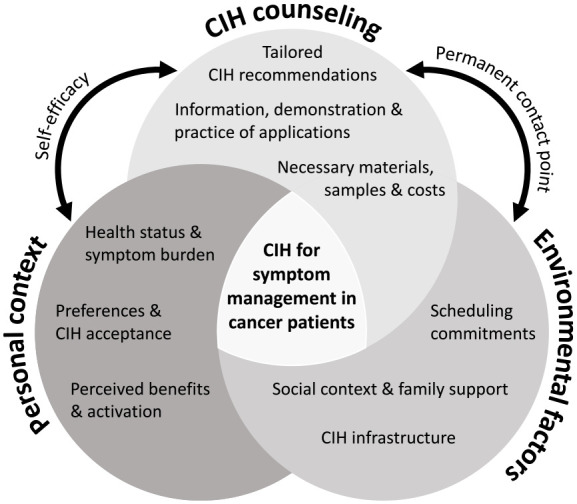

Several factors influenced the extent to which participants implemented the CIH recommendations they received during counseling sessions. These factors relate to three different levels: the participants’ personal context, environmental factors, and the CIH counseling process. CIH counseling was associated with both personal and environmental factors, influencing them through patient-centered interactions, providing a (permanent) point of contact for addressing CIH-related issues, and enhancing participants’ self-efficacy (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Factors affecting the utilization of complementary and integrative healthcare (CIH) applications for symptom management in cancer patients who received CIH counseling.

Factors pertaining to the counseling process encompassed the characteristics of the recommended CIH measures (scope and effort of the recommendations), the supporting informational material provided, and the participants’ self-efficacy in implementing the CIH interventions. Self-efficacy refers to the belief an individual has in their ability to independently apply the CIH recommendations and overcome difficulties in implementation. 34 Many participants (n = 17) reported that the explanations they received during counseling sessions gave them enough confidence and self-efficacy to apply the CIH measures at home. This was particularly true for simple measures resembling everyday activities (e.g., preparing herbal teas, taking nutritional supplements). In addition, participants reported that they perceived the supporting informational material and written instructions, complemented with illustrations, to be beneficial in comprehending how to apply the CIH applications at home. However, some participants (n = 3) expressed uncertainty about applying acupressure, fearing hitting the wrong pressure points and causing a negative effect. Additionally, lack of motivation was identified as a hindering factor for participants regarding their self-efficacy to exercise.

Moreover, the extent of effort and scope required for the CIH measures themselves was also cited as a significant determining factor in their implementation. Participants mentioned herbal teas, aromatherapy, mouthwashes, dietary recommendations, and certain oils and creams (for pain or dry skin) as measures that can be easily integrated into everyday life. In contrast, some participants (n = 8) indicated a tendency to use more complex and time-consuming CIH applications that require preparation, such as baths against neuropathy or herbal poultices, less consistently or not at all.

In addition to the characteristics of the recommended CIH applications and their communication during counseling sessions, participants also reported other personal and environmental factors influencing the integration of the recommendations. These factors included participants’ health status but not their treatment approach or cancer type. Many participants (n = 18) reported that they had difficulties applying specific CIH measures due to illness-related limitations (e.g., fatigue, pain, or physical constraints), while others (n = 10) no longer required the CIH applications as their symptoms had improved. For instance, a participant (female, 64 years) suffering from fatigue mentioned that she was only able to implement simple, “little” measures like a “mouth rinse” while it seemed “difficult to implement” more complex measures as she did “not have the energy to do exercises” (R28). This demonstrates that the influence of the CIH applications’ complexity on their application in patients’ daily lives was also associated with their health status. Participants cited scheduling commitments, often related to their health status, as another factor that affected the application of the recommended CIH treatments. The numerous diagnostic and treatment appointments left them little time and energy, making it challenging to integrate the recommended treatments into their routine.

Many participants (n = 14) perceived that assistance and support from their relatives and social environment were facilitating factors for successfully applying the recommended CIH measures, particularly for more complex applications. On the other hand, four participants stated that their family responsibilities hindered their ability to effectively incorporate the recommended measures into their daily routines, as they struggled to find time to apply them.

The participants’ personal preferences, acceptance, and openness toward specific CIH treatments also impacted their implementation. For instance, some individuals (n = 6) expressed disbelief in the effectiveness of acupressure and, therefore, chose not to pursue it further. Similarly, when it came to aromatherapy or herbal teas, participants (n = 4) who reported that they did not like the smell of certain aromatic oils or the taste of herbs were less likely to continue using them. In such cases, it was helpful if participants were offered samples during the consultation and allowed to test different fragrances, herbal compositions, or acupressure points beforehand. A patient diagnosed with breast cancer (female, 30 years) reported that providing aromatic oil samples during counseling helped her overcome her initial skepticism about aromatherapy. The opportunity to try different fragrances allowed her to find one that suited her preferences. This enabled her to start using it directly, benefitting from its symptom management properties against her nausea:

With aromatherapy, they (the counselors) had [lemon oil], but they also let me try bergamot, which I liked even better, and therefore I got a sample of the bergamot oil. That helped me a lot. —[. . .] But I don’t think I would have bought it without the sample. —[Firstly] because of my skepticism [. . .] and because these oils are expensive. I was just glad they gave it to me. (R17)

The quote indicates that the costs associated with procuring materials for the recommended CIH measures also affect implementation. The CCC-Integrativ intervention provided free counseling sessions on evidence-based CIH treatments to cancer patients. However, participants were responsible for obtaining and paying for the materials required to implement the recommended CIH measures (e.g., aroma oils, acupressure patches, herbal teas, and nutritional supplements). Some participants (n = 2) were taken aback by this and wished for more transparency regarding the costs associated with implementing the counseling recommendations. They also expressed a desire for health insurance to cover these costs in the future. Additionally, one participant had difficulty affording the costs associated with the CIH measures as he was already facing financial hardships due to his cancer diagnosis.

Another challenge cited by participants in implementing the counseling recommendations was the lack of infrastructure in CIH health providers. Participants (n = 9) reported difficulty finding suitable providers, especially when recommended sports, yoga, massages, or mistletoe therapy. This is evident in the following quote from a participant diagnosed with breast cancer (female, 39 years) who expressed doubt about whether the recommended yoga school offers classes that fit her schedule:

What I have not been able to integrate so far is sports—and I don’t know whether I will be able to do it. [A yoga school] that works together with the university hospital was recommended to me, but probably the [course] hours are [not feasible for working people]. [. . .] This offer is too thin. It is always unfortunate when the only alternative is a single yoga school.” (R35)

Future CIH Utilization

Regarding future utilization of CIH and maintenance of the counseling recommendations, most participants (n = 35) indicated that they could envision utilizing CIH applications for similar health issues beyond the completion of their cancer treatment:

If my sleep problem persists for an extended period, I will undoubtedly continue using them (the recommended applications). I have observed that acupressure is quite effective for me, and if I encounter [any other] difficulties in the future, I will consider using it again. (R9; female, 55 years)

Perceived Outcomes

The participants’ inclination to sustain the counseling recommendations in the future was linked to their comments on the perceived outcomes of the counseling intervention.

Personal Benefits

Most participants (n = 30) mentioned personal benefits such as effective symptom control, improved well-being using CIH measures, and a greater sense of control and activation. A patient with breast cancer (female, 30 years) stated that she had significantly benefitted from aromatherapy and acupressure, which “helped to prevent the worst of nausea” (R17). Nevertheless, she was aware that they could only provide limited relief, and she “appreciated the doctor’s reminder that these are just little components and do not turn [. . .] nausea on and off” (R17). She considered it positive to play an active role in symptom management, and “feeling like [she] was actively contributing to [her] treatment was nice instead of just enduring it passively” (R17). Seven participants indicated that the recommended interventions had limited to no impact on their symptoms and overall well-being. These participants frequently noted that their symptoms were particularly severe and required potent conventional medications to manage them.

However, participants reported personal benefits beyond symptom control that contributed to their overall well-being. These benefits included confirmation of their previous behavior and use of CIH measures by the interprofessional counseling team (n = 18) and meeting their informational needs regarding CIH (n = 27), providing them with a feeling of security and hope (n = 22). A substantial number (n = 20) of participants expressed a sense of activation and empowerment through the patient-centered counseling approach. They conveyed the intention to delve deeper into CIH and self-care practices. One participant (female, 57 years) described how the “warm atmosphere” and support from the counselors helped to alleviate fears and feel empowered to take responsibility for her health:

I went home feeling very inspired afterward. [. . .] The conversation was like an [eye-opener]: Yes, I can do something myself. The [counselors] took away my fears: I can do everything, eat everything, drink coffee, etc. I was a little unsure [about these things] before. [. . .] I had somehow relinquished responsibility [for my health]. During the conversation, [. . .] I became aware of my own responsibility again and that I can do something myself. (R1)

Benefits for the Healthcare System

In addition to personal benefits, participants (n = 18) perceived that counseling on CIH for symptom management could also benefit the healthcare system, such as providing evidence-based education and information on CIH, improving patient care, and ultimately reducing healthcare costs. One participant (male, 68 years) mentioned that the counseling program could serve as a reliable point of contact for questions or concerns about CIH and believed such services would become “increasingly important because many people [. . .] experience insecurity or discomfort” (R27). According to his statement, the CIH counseling program could improve patient care and reduce healthcare costs by avoiding unnecessary doctor visits:

I found this facility very good [. . .]. [Such counseling] is essential and saves the healthcare system much money, and it makes patient care much easier because they have a reliable point of contact. That is a huge advantage. [. . .] I think this (integration of CIH) has a future. (R27)

Unmet Expectations

Apart from the advantages of the counseling program, some participants mentioned that not all their expectations were met. Four individuals had expected the program to provide specific CIH recommendations for tumor control as an alternative to conventional treatment rather than just suggestions for symptom management. Additionally, some individuals (n = 5) expressed disappointment that the program only consisted of counseling and did not involve directly applying CIH measures.

Suggestions for Improvement

Participants (n = 14) also expressed a desire for long-term support from the counseling team as an unfulfilled expectation and an area for improvement. They perceived that having a permanent point of contact for questions and concerns regarding CIH could be beneficial, especially as their symptoms changed throughout treatment and new questions arose. A participant (female, 63 years) with a palliative treatment approach specifically wished to have the option to contact the counseling program again to discuss further concerns on CIH:

The more chemotherapy treatments I receive, the more problems will arise in the long run. [Therefore], it would have been nice if I could have contacted [the counseling team] again to ask, “Could I have another conversation? I have a few more questions.” Or even just by phone. But unfortunately, that was not possible. (R26)

Furthermore, participants (n = 3) expressed the need for better networking and information exchange between the counseling team and other healthcare providers to maximize the program’s benefits. They also suggested that the program should be more extensively promoted and made more accessible. In this context, participants (n = 8) noted that the counseling program was not well-known among other patients and indicated that it could be helpful if the treating physicians would actively inform their patients about the program. Some individuals (n = 4) emphasized the importance of providing information about the opportunity of CIH counseling shortly after diagnosis or early in the treatment process during inpatient stays. Lastly, participants (n = 6) mentioned that finding suitable providers for applying CIH measures was a difficulty in implementing the recommended measures, as described earlier. They suggested that providing detailed information on and helping them find suitable providers in the counseling process could improve this barrier.

Discussion

This study aimed to investigate patients’ experiences with a CIH counseling intervention to explore the factors that influence the integration of CIH recommendations into patients’ daily lives and how patients perceive the outcomes of the counseling intervention. The present study’s findings contribute to understanding the intricate and individualized nature of patients’ adoption of CIH recommendations for symptom management. Based on the analysis of the individual interviews, it was found that participants had incorporated many of the CIH recommendations provided during the counseling sessions into their daily routines. Several factors appeared to influence the implementation of the recommended CIH applications in the outpatient setting, including the characteristics of the counseling process and the applications themselves, as well as the patients’ personal context and external factors.

Among the factors that hindered the implementation of recommended CIH interventions were the substantial effort needed for treatment application and preparation (e.g., baths, compresses), limitations imposed by the disease itself (e.g., fatigue, pain), challenges in obtaining necessary materials, associated costs, and lack of infrastructure for CIH. These findings are consistent with prior research on complementary practices, such as physical activity programs, indicating that barriers to regular physical activity in cancer patients include symptoms like fatigue or reduced physical functioning, time constraints, and the lack of necessary equipment, facilities, and space. 35

Factors that facilitated the implementation of CIH recommendations in the current study included the availability of simple and easily manageable CIH measures (e.g., herbal teas), the provision of additional information materials with information on their application, the provision of samples during counseling sessions, family support, and high levels of self-efficacy in applying the CIH measures. These results support previous research findings on promoting self-management in cancer patients, highlighting the importance of family support 35 and high levels of self-efficacy 36 and suggesting providing information and specific resources tailored to patient needs. 37 The current study’s findings also align with research on the implementation of integrative oncology in cancer care, 38 indicating that a supportive environment with caregiver support facilitates the use of CIH for symptom management. At the same time, the lack of referral systems to credible CIH services hinders the integration of integrative cancer care. 38

The statements made by participants in the current study suggest that individual factors, like health status and recommendation complexity can interact, influencing the implementation in patient’s daily lives. These findings align with other studies indicating that cancer patients’ management of disease- and treatment-related symptoms is a complex and personal process.39,40 In the CCC-Integrativ study, CIH counseling was related to personal and environmental factors in that it influenced them through patient-centered interactions and enhanced participants’ self-efficacy (see Figure 2). Self-efficacy is defined as the individual’s belief in their ability to control health habits. 41 Participants reported that the thorough explanation and demonstration of CIH recommendations and the chance to try different samples helped them decide which CIH measures to use. This tailoring of recommendations to participants’ personal needs in the counseling context and the detailed explanation of the applications seemed to facilitate the implementation of the recommendations and strengthened the participants’ self-efficacy.

Moreover, participants who received FC were more inclined to independently adapt the recommendations to their daily needs, such as simplifying the preparation of compresses or using alternative fragrances for aromatherapy. This indicates greater familiarity with CIH concepts during the counseling process and increased self-efficacy in implementing the CIH measures due to the counseling program.

These findings are noteworthy, considering a quantitative survey by Hübner et al., 42 which found that self-efficacy was not associated with the utilization of CIH when patients employed CIH applications for non-specific goals (e.g., strengthening the body’s own forces or the immune system). Therefore, the authors, recommend a proactive discussion with patients about the goals of CIH usage, such as addressing side effects and tailoring the CIH measures to align with the specific patient’s needs. In the CCC-Integrativ study, this approach was implemented during individual counseling sessions, leading to an enhancement in self-efficacy and patient activation associated with symptom management. In addition, Hübner et al. 42 did not investigate the specific factors influencing the independent long-term implementation of CIH recommendations. The present study’s qualitative approach aims to fill this gap by interviewing patients about their use of CIH and the influencing factors in everyday life.

The findings of the present study also align with Social Cognitive Theory 41 and Hoffman’s Theory of Symptom Self-Management,43,44 emphasizing the significance of self-efficacy as a key determinant of health behavior. Interventions to enhance self-efficacy can effectively promote patient engagement and empowerment in maintaining symptom self-management strategies. 44

Coolbrandt et al. 45 observed that coping strategies for chemotherapy-related symptoms might be influenced by personal and external factors, including the perceived symptom burden, and patients’ beliefs about how much control they have over the symptoms. Similarly, the current study revealed that participants’ health status, symptom burden, individual preferences, and openness towards new and unfamiliar symptom management strategies (e.g., acupressure and aromatherapy) were significant factors affecting the integration of CIH recommendations. Moreover, the perceived benefits of the CIH applications and participants’ activation level determined whether they used and continued the CIH recommendations. Most participants in the current study reported significant benefits from the CIH recommendations they received during counseling sessions. These treatments effectively aided in symptom management and positively influenced their overall well-being and activation level. Consequently, several participants expressed a desire to sustain the utilization of these CIH measures even after completing their cancer treatment. These findings support the efficacy of CIH as a symptom management strategy for cancer patients. 46 Nevertheless, participants with an exceptionally high symptom burden appeared to derive limited benefits from the CIH applications, as they often did not provide sufficient relief. In a study by Lopez et al. 47 investigating the effects of outpatient integrative oncology consultations, the most significant improvements in symptom burden were observed among patients with moderate to severe symptoms. Building upon these findings, the current study’s results suggest that patients with a moderate symptom burden experience the most significant benefits from incorporating CIH applications for symptom management into their cancer care.

Alongside the benefits of the CIH recommendations on symptom control, participants reported interpersonal experiences within the counseling context that positively influenced their overall well-being. Receiving advice from an interprofessional team instilled them with confidence and a sense of security. The patient-centered approach made them feel empowered and hopeful, fostering the belief that they could actively contribute to their health. In this regard, interprofessional counseling serves as a source of emotional support, considered an essential factor for successfully implementing CIH services. 38 In addition, enhancing patient activation levels through CIH counseling may positively impact the integration of CIH recommendations for symptom management, given that individuals with heightened activation levels show increased interest and a greater tendency to engage in CIH practices. 42

Participants’ desire for long-term counseling support during their disease course and their assertion of a lack of credible CIH points of contact underscores the importance of these interpersonal aspects. The emphasis on establishing strong patient-provider partnerships to empower and activate patients in taking control of their self-care aligns with the Chronic Care Model (CCM) principles. 19 The CCM recognizes that treatments, symptoms, and patients’ personal goals may change over the cancer care continuum, which may require adjustment and modification of symptom management strategies. The distribution of three counseling sessions on CIH over three months of patients’ disease course in the CCC-Integrativ study, constitutes an approach to address this aspect. Nevertheless, participants in the current study indicated that they would desire an ongoing point of contact and further support to address their concerns about CIH. These findings align with research on factors enhancing cancer patients’ self-management in an outpatient setting, suggesting that besides addressing informational needs, the regular reassessment of symptoms and mental health needs throughout the treatment course is essential for effective symptom management. 37 In this respect, consideration should be given to expanding CIH counseling programs and establishing a permanent point of contact for CIH concerns.

Further potential for improvement to influence environmental factors relates to participants’ expressed need for further promotion of the program and the not yet fulfilled expectation for health insurance companies to cover the costs of necessary materials. The lack of funding for patients to access CIH services is already known to be a limiting factor for the sustainable implementation of CIH in standard care. 38 Therefore, policymakers could facilitate the implementation of CIH programs by initiating health insurance funding. Furthermore, claims of inadequate networking and information sharing between the CIH counseling program and other healthcare providers, as cited by participants in the current study, indicate a desire for better integration of the counseling program into standard cancer care. These findings are consistent with previous research on patients’ experiences of integrative oncology awareness and use, which suggests that patients request earlier information from their providers about CIH for symptom management and CIH service recommendations. 48

Future CIH counseling programs should consider these patient preferences and leverage the potential of a permanent CIH counseling point to serve as an intermediary between the various practitioners involved in patient care and provide information about credible CIH providers (see Figure 2). This could further improve the environmental factors that influence the use of CIH for symptom control in cancer patients and save costs in the healthcare system through better patient care and reduced use of various healthcare services.

Implications for Future Research and Integrative Healthcare

The findings of this study provide valuable insights into implementing innovative CIH approaches and developing future interventions in CIH counseling for symptom control and patient activation (Table 1). Given the individual nature of factors influencing cancer patients’ ability and engagement in applying the recommended CIH measures, it is essential to tailor supportive care to patients’ specific needs. By considering patients’ personal circumstances, preferences, support systems, and level of motivation to engage in more complex CIH applications, healthcare providers can tailor CIH recommendations for integration into patients’ daily lives. In addition to providing samples (e.g., oils for aromatherapy), mentioning specific points of contact for CIH applications, such as local yoga studios, could also reduce the barriers to implementation. The participants’ recognition of the potential benefits for the healthcare system and their expressed desire for continued support through the counseling program underscores the importance of establishing a permanent CIH counseling structure to enhance the provision of cancer care. In this context, efforts should be made toward health insurance covering the expenses of CIH counseling services, ensuring accessibility for all patients. Additionally, emphasis should be placed on fostering intensive collaboration among diverse healthcare providers.

Table 1.

Implications and Recommendations for Future Research in Complementary and Integrative Healthcare (CIH) Counseling and Integrative Healthcare.

| Implications for future research | Recommendations for integrative healthcare |

|---|---|

| • Further development of CIH counseling interventions to strengthen cancer patients’ sense of control and self-efficacy in symptom management | • Supportive care tailored to the specific patient’s needs and prior knowledge about CIH |

| • Further exploration of the impact of an interdisciplinary patient-centered approach on patient activation and symptom management | • CIH counseling with considering patients’ personal circumstances, preferences, support systems, and level of motivation to implement CIH applications |

| • Further research on other interprofessional constellations within interventions to improve cancer patients’ healthcare | • Provision of informational material and samples (e.g., aromatherapy oils), mentioning of specific points of contact for CIH applications such as local yoga studios |

| • Examination of advantages and challenges associated with the integration of CIH counseling for the healthcare system | • Establishment of a permanent point of contact for health needs related to CIH |

| • Funding of CIH counseling programs through healthcare insurance and fostering close collaboration among healthcare providers |

Future research on the implementation of CIH counseling approaches to assist patients in symptom management might target critical determinants, such as patients’ perceived level of control, self-efficacy, and activation. Strategies and interventions that enhance patients’ belief in their ability to cope with symptoms effectively can empower them to actively participate in managing their care. 44 Moreover, our findings suggest that a patient-centered approach emphasizing a solid patient-provider partnership within an interprofessional team is essential, as it can positively influence patient activation. In this context, further research is needed on additional interprofessional constellations in the context of interventions to improve healthcare for cancer patients. Finally, given the anticipated benefits expressed by participants in this study, it is essential to evaluate the advantages and challenges linked to integrating CIH counseling into standard cancer care for the healthcare system.

Limitations and Strengths

To the best of our knowledge, this study represents the first investigation of cancer patients’ experiences with the implementation of an interprofessional CIH counseling program within standard cancer care in Germany. By examining a diverse range of patient profiles across four CCCs, valuable insights were gathered into patient perceptions and the factors influencing the integration of recommended CIH applications into their daily lives. Nonetheless, it is essential to acknowledge the study’s constraints, encompassing potential selection bias among patients who agreed to participate in the interview study, potentially affecting the results’ credibility. However, it is worth noting that the trustworthiness of the findings was enhanced by the broad variation in participants’ experiences with the CIH counseling observed in the interviews, which was achieved through the careful sampling strategy employed. This variation contributes to the richness and diversity of the data, strengthening the validity of the study’s results. Additionally, it is crucial to consider the possibility of recall bias, as participants may not accurately remember all aspects and details of the counseling program.

Moreover, participants may have intentionally concealed information, for example, about recommendations they did not implement, in the sense of socially desirable response behavior. Accordingly, other unexamined factors may influence the implementation of CIH recommendations. These potential biases should be considered when interpreting the current study’s findings.

Another potential limitation of the study is that data collection occurred during the Covid-19 pandemic. Since cancer patients are considered particularly vulnerable to infectious diseases, they were advised to minimize unnecessary contacts, which could have affected their willingness to participate in the counseling program and interview study (selection bias). The pandemic may have also posed barriers to accessing CIH infrastructure, as many institutions offering physical exercise or yoga classes had to close temporarily. These circumstances might have made it more challenging for participants to find suitable CIH providers. These aspects may vary or may be experienced differently under non-pandemic circumstances. Nevertheless, our findings mainly contribute to the awareness of how such external factors can either facilitate or impede patients’ implementation of CIH recommendations into their daily routines.

Conclusions

Various factors shape the extent to which patients integrate and apply CIH recommendations in their daily lives. While characteristics of the intervention itself, including individually tailored counseling about CIH, informational materials, and the provision of samples, can impact implementation, other factors, such as patients’ personal context and environmental factors, also seem to be important. Our findings suggest that by recognizing and addressing these multifaceted factors, enhancing patients’ self-efficacy, and providing a permanent point of contact, healthcare providers can effectively support patients in implementing CIH applications and maximizing their benefits for symptom management.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all staff members and patients participating in the CCC-Integrativ study and process evaluation.

Appendix 1

Category System with Main Categories and Associated Subcategories Discussed in this Article.

| Main category | Subcategories | Sub-subcategories | Description | Example citation: |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Implementation of CIH a -recommendations | Integration into everyday life | Participants’ integration of the counseling recommendations into their daily lives, including their statements regarding the timing and regularity of implementing the CIH measures, which applications they have yet to try, and any modifications or abandonment of certain measures | “I start in the evening; in the evening I have the most to do. >Laughs< That’s when I make this herbal poultice for the heart. First, I have to heat up my cherry stone pillow, so that it gets nice and warm, and then I put it on my chest. And while I’m putting it on, I also put a little bit of orange oil cream around my nose, so that I have the smell of it as well.” (R36 b ; female, 74 years) | |

| Factors affecting the integration | Self-efficacy in application | Participants’ statements regarding their confidence in applying the recommended CIH measures, including whether they believe they can carry them out even when problems or difficulties arise. For example, expressing uncertainty in applying hot compresses due to the risk of scalding or feeling unsure about locating acupressure points and therefore consulting a physiotherapist | “Something that I have not done, for example, (is the peeling) with the salt and the oil, because I am a bit afraid. You must go into the shower to do it and I’m a little afraid of falling [. . .] and with oil [on] the feet—and with salt. . . I didn’t do that.” (R26; female, 63 years) | |

| Supporting information material | Statements about additional materials provided to support participants in implementing the recommended CIH counseling content, including informational recipes, supplementary informational materials, the consulting letter, and participants’ own notes | “(The consultation letter) was a good summary of what we had talked about. Because if that is only discussed in the consultation, then it gets lost at some point. That was important for me, that I got a (written) summary.” (R40; male, 44 years) | ||

| Scope and effort of recommendations | Participants’ statements regarding the influence of the scope and effort of CIH recommendations on their implementation, and their perceptions of which measures were complex or simple | “The footbaths are a bit time consuming, so I don’t always do that.” (R9; female, 55 years) | ||

| Health status | Statements regarding the impact of participants’ health conditions on the implementation of recommendations in their everyday lives, including difficulties due to fatigue or pain, improvements in symptoms leading to the discontinuation of certain measures | “I suffer from severe fatigue and this also takes away my motivation to do sports, which I loved to do; cycling and Nordic walking. Nordic walking—I can’t do it anymore also because the skin [on my feet is loosening] (due to hand-foot syndrome).” (R29; male, 63 years) | ||

| Main category | Subcategories | Sub-subcategories | Description | Example citation: |

| Scheduling commitments | Participants’ statements regarding the impact of scheduling commitments on the implementation of CIH recommendations, such as difficulties in attending yoga classes due to a lack of time caused by multiple therapy appointments | “(Yoga) I haven’t done yet because I always have my appointments at the university clinic on Tuesdays and then I can’t attend (the classes) regularly. But when the chemotherapy is over, I’ll have a look at it.” (R39; female, 56 years) | ||

| Relatives | Statements about the involvement of relatives in the implementation of CIH measures in participants’ daily lives, including the tasks they assume in caregiving, such as providing support in the application or selection of appropriate CIH measures | “The hot compresses I find difficult, but my daughter-in-law has done it for me and managed it quite well. [. . .] So, my son and my daughter-in-law, they also read through (the counseling letter) and [. . .] my son ordered me these oils.” (R36; female, 74 years) | ||

| Personal preferences | Statements indicating that participants have not incorporated the recommendations into their daily lives due to personal preferences, such as not liking the scent of lavender for aromatherapy | “I tried these oil pads in the neck (against pain), but then realized that Aconit oil is not my preference at all, so I changed the oil (to Solum oil).” (R31; female, 55 years) | ||

| Materials required | Reports from participants regarding the materials they needed to implement the CIH recommendations and the steps they took to obtain them, including any funding required. Participants’ statements about whether they received samples or specimens of aromatic oils or other supportive materials during the consultation | “Then [the recommendation of] tea and sea buckthorn pulp oil, I ordered that right away and the rose hydrolate [. . .] to spray on the skin, I also bought that today.” (R8; female, 65 years) | ||

| CIH-infrastructure | Participants’ reports on the extent to which they sought external CIH services, such as yoga classes, acupuncture, MBSR c classes, or apps, as part of implementing the recommendations, and their perceptions of these services and their accessibility | “[They recommended me] massages and acupuncture, but that’s always difficult to get an appointment for. It sounds good that the possibility exists, but when you call for an appointment, they just say ‘Yes, we’ll put you on the waiting list’.” (R33; male 69 years) | ||

| Future CIH utilization | Participants’ assessment of whether they intend to continue using CIH measures in the future, even after completing their cancer treatment | “I think that even if the therapy is completed, I’m still not out of the whole thing, that will certainly also be a psychological development, and maybe I won’t be able to sleep every now and then. So, I will certainly continue (the measures).” (R30; female, 65 years) | ||

| Main category | Subcategories | Sub-subcategories | Description | Example citation: |

| Perceived outcomes | Personal benefits | Influence on symptom burden and well-being | Participants’ statements regarding the extent to which they perceive the benefits of the counseling program and CIH recommendations as an improvement in symptom burden and their overall well-being. Additionally, their reasons for perceiving low benefits are included | “The flax seeds, that was a good recommendation and helped with the stool regulation and also the liver wraps, I found to be very, very positive.” (R32; male, 53 years) |

| Confirmation of current behavior | Participants’ reports indicating that they have benefited from confirmation that the CIH measures they are already using, and their current lifestyle align with the principles of CIH and are considered safe. This includes confirmation of not only specific CIH measures already in use but also general behaviors or plans for the near future | “To hear that I’m already doing a lot of things right was good - and to hear that a (special) diet and [giving up sugar] etc., that this doesn’t necessarily help much (in terms of fighting the tumor). To get confirmation in this regard [. . .] that I’m already eating well.” (R24; female, 27 years) | ||

| Meeting CIH information needs | Statements highlighting the benefits of the counseling intervention in acquiring reliable information on the topic of CIH, as well as emphasizing the need to integrate the topic of CIH into mainstream care more extensively using evidence-based recommendations | “I would definitely recommend (the counseling program), because it is a professionally evidence-based advice (on the subject of CIH) and that is much better than if you look for the information yourself, because there is sometimes very contradictory information on this subject in circulation.” (R11; female, 40 years) | ||

| Meeting emotional needs | Statements that participants benefited from the counselors’ attention and patient-centered interpersonal interaction, that counseling gave them hope and/or relief in dealing with the cancer diagnosis | “As it were, you are very closely accompanied. You always hear something [from the program], you always see something, you always get something and so on, you feel protected. That’s an important psychological aspect, that you don’t feel left alone.” (R27; male, 68 years) | ||

| Activation | Reports from participants indicating that they feel an enhanced sense of self-efficacy and activation as result of their participation in the counseling program. For example, through expressing an increased motivation to exercise, prioritizing self-care, or engaging in other positive behavioral changes. . This positive impact can be observed through increased motivation to exercise, a greater emphasis on self-care, and the adoption of other positive behavioral changes | “It has strengthened me in what I have started. [. . .] my [inner] fighter has risen again [. . .] my own energy has become more active again, [. . .] it also made me realize in both conversations that somehow things are improving again.” (R22; female, 61 years) | ||

| Main category | Subcategories | Sub-subcategories | Description | Example citation: |

| Benefits for the healthcare system | Participants’ statements that extend beyond personal benefits, specifically their assessment of the usefulness and importance of the counseling service for the overall healthcare system, and their reasons for such assessment | “The medical experts are too busy with other things and can’t provide the holistic [treatment approach] that I missed so much or that I like so much, and they shouldn’t, that’s not what they’re there for. That’s why [such a counseling program] would actually be good, and that’s why I would recommend it.” (R35; female, 39 years) | ||

| Unmet expectations | Statements about participants’ expectations that were not fulfilled in the counseling program, such as the lack of direct practical application of CIH measures | “I was hoping that my [cancer] would be addressed specifically, not [. . .] the side effects that I’m currently experiencing with my indigestion. That’s important for me too, but I thought that they would focus more on the disease and perhaps recommend naturopathy or something. . . That was lacking.” (R6; male, 64 years) | ||

| Suggestions for improvement | Concrete suggestions for improvement provided by participants on how the counseling intervention can be made even more effective in the future, such as increasing advertising efforts | “What might also be interesting would be to link the consultation with what happens during the inpatient stay. For example, the treating physicians actually incorporate something [from the consultation] into the medication plan officially. I don’t know if that’s possible, because you're still in the process of establishing the program.” (R23; male, 46 years) |

CIH, complementary and integrative healthcare.

R plus number, participant’s pseudonym.

Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction.

Footnotes

Authors’ Note: This article is based on the first author’s doctoral dissertation at the University of Heidelberg.

Authors Contribution: NK and HD developed the study’s concept and design. HD collected and processed data, while HD and UB performed data coding. HD carried out data analysis for thematic interpretation and wrote the initial manuscript, which was critically reviewed by NK. CM, SJ, HD, NK, and UB engaged in discussions regarding the data, coding system, and thematic interpretation. All authors have reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement: The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author(s). The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The current study is part of the process evaluation of the CCC-Integrative project, which received support from the Innovations fonds of the Federal Joint Committee Berlin 2019-2022 (funding years: October 2019-March 2023) Grant number: 01NVF18004. The study’s funder was not involved in the study’s design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, or manuscript preparation. As this is a government grant, there are no commercial interests at play.

Ethics Approval: The study is part of the process evaluation which was approved by the Medical Faculty of Heidelberg Ethics Committee, No. S-307/2020, on November 24, 2020.

Patient Consent: Participants were provided with both verbal and written information regarding the study’s objectives. Prior to their involvement in the interview study, all participants provided written informed consent.

Clinical Trial Registration: The study is registered with DRKS: DRKS00021779; https://drks.de/search/en/trial/DRKS00021779

ORCID iD: Helena Dürsch  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9867-3777

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9867-3777

References

- 1. Keene MR, Heslop IM, Sabesan SS, Glass BD. Complementary and alternative medicine use in cancer: a systematic review. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2019;35:33-47. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2019.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Drozdoff L, Klein E, Kiechle M, Paepke D. Use of biologically-based complementary medicine in breast and gynecological cancer patients during systemic therapy. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2018;18(1):259. doi: 10.1186/s12906-018-2325-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. World Health Organization. Program on Traditional M. WHO Traditional Medicine Strategy 2002-2005. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 4. National Institutes of Health. Exploring the science of complementary and integrative health. National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bozza C, Gerratana L, Basile D, et al. Use and perception of complementary and alternative medicine among cancer patients: the CAMEO-PRO study. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2018;144(10):2029-2047. doi: 10.1007/s00432-018-2709-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kessel KA, Lettner S, Kessel C, et al. Use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) as part of the oncological treatment: survey about patients’ attitude towards CAM in a University-Based Oncology Center in Germany. PLoS One. 2016;11(11):e0165801. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0165801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bonacchi A, Toccafondi A, Mambrini A, et al. Complementary needs behind complementary therapies in cancer patients. Psychooncology. 2015;24(9):1124-1130. doi: 10.1002/pon.3773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Foley H, Steel A. Patient perceptions of clinical care in complementary medicine: a systematic review of the consultation experience. Patient Educ Couns. 2017;100(2):212-223. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2016.09.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Guerra-Martín MD, Tejedor-Bueno MS, Correa-Casado M. Effectiveness of complementary therapies in cancer patients: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(3):1017. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18031017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hilfiker R, Meichtry A, Eicher M, et al. Exercise and other non-pharmaceutical interventions for cancer-related fatigue in patients during or after cancer treatment: a systematic review incorporating an indirect-comparisons meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2018;52(10):651-658. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2016-096422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Beijers AJM, Bonhof CS, Mols F, et al. Multicenter randomized controlled trial to evaluate the efficacy and tolerability of frozen gloves for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy. Ann Oncol. 2020;31(1):131-136. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2019.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Stub T, Quandt SA, Arcury TA, et al. Perception of risk and communication among conventional and complementary health care providers involving cancer patients’ use of complementary therapies: a systematic review. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2016;16(1):353. doi: 10.1186/s12906-016-1326-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Deng GE, Frenkel M, Cohen L, et al. Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for integrative oncology: complementary therapies and botanicals. J Soc Integr Oncol. 2009;7(3):85-120. doi: 10.2310/7200.2009.0019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Schofield P, Diggens J, Charleson C, Marigliani R, Jefford M. Effectively discussing complementary and alternative medicine in a conventional oncology setting: communication recommendations for clinicians. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;79(2):143-151. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.07.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. German Guideline Program in Oncology. (German Cancer Society, German Cancer Aid, AWMF): interdisciplinary evidenced-based practice guideline for the early detection, diagnosis, treatment and follow-up of breast cancer, long version 4.4, May 2021, AWMF Registration Number: 032/045OL. Accessed May 2023. http://www.leitlinienprogramm-onkologie.de/leitlinien/mammakarzinom/

- 16. Stie M, Jensen LH, Delmar C, Nørgaard B. Open dialogue about complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) integrated in conventional oncology care, characteristics and impact. A systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2020;103:2224-2234. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2020.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Roter DL, Yost KJ, O’Byrne T, et al. Communication predictors and consequences of Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM) discussions in oncology visits. Patient Educ Couns. 2016;99(9):1519-1525. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2016.06.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rogge AA, Helmer SM, King R, et al. Effects of training oncology physicians advising patients on complementary and integrative therapies on patient-reported outcomes: a multicenter, cluster-randomized trial. Cancer. 2021;127:2683-2692. doi: 10.1002/cncr.33562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. McCorkle R, Ercolano E, Lazenby M, et al. Self-management: enabling and empowering patients living with cancer as a chronic illness. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61(1):50-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Baydoun M, Barton DL, Arslanian-Engoren C. A cancer specific middle-range theory of symptom self-care management: a theory synthesis. J Adv Nurs. 2018;74(12):2935-2946. doi: 10.1111/jan.13829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Howell D, Mayer DK, Fielding R, et al. Management of cancer and health after the clinic visit: a call to action for self-management in cancer care. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2021;113:523-531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Valentini J, Fröhlich D, Stolz R, et al. Interprofessional evidence-based counselling program for complementary and integrative healthcare in patients with cancer: study protocol for the controlled implementation study CCC-Integrativ. BMJ Open. 2022;12(2):e055076. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-055076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Skivington K, Matthews L, Simpson SA, et al. A new framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions: update of Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ. 2021;374:n2061. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n2061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, Michie S, Nazareth I, Petticrew M. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ. 2008;337:979-983. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a1655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lewin S, Glenton C, Oxman AD. Use of qualitative methods alongside randomised controlled trials of complex healthcare interventions: methodological study. BMJ. 2009;339:732-734. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b3496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bossert J, Mahler C, Boltenhagen U, et al. Protocol for the process evaluation of a counselling intervention designed to educate cancer patients on complementary and integrative health care and promote interprofessional collaboration in this area (the CCC-Integrativ study). PLoS One. 2022a;17(5):e0268091. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0268091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Broom A. Using qualitative interviews in CAM research: a guide to study design, data collection and data analysis. Complement Ther Med. 2005;13(1):65-73. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2005.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Palinkas LA, Horwitz SM, Green CA, Wisdom JP, Duan N, Hoagwood K. Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2013;42:533-544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dürsch H, Boltenhagen U, Mahler C, Joos S, Szecsenyi J, Klafke N. A qualitative analysis of cancer patients’ perceptions of an interprofessional counseling service on complementary and integrative healthcare. Qual Health Res. 2024:10497323241231530. doi: 10.1177/10497323241231530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kuckartz U, Rädiker S. Analyzing Qualitative Data with MAXQDA: Text, Audio, and Video. Cham: Springer; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 31. MAXQDA 2022. VERBI Software [computer software]; 2021. maxqda.com [Google Scholar]

- 32. Klafke N, Mahler C, von Hagens C, Blaser G, Bentner M, Joos S. Developing and implementing a complex Complementary and Alternative (CAM) nursing intervention for breast and gynecologic cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy—report from the CONGO (complementary nursing in gynecologic oncology) study. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24(5):2341-2350. doi: 10.1007/s00520-015-3038-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Klafke N, Mahler C, von Hagens C, et al. How the consolidated framework for implementation research can strengthen findings and improve translation of research into practice: a case study. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2017;44:E223-E231. doi: 10.1188/17.ONF.E223-E231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev. 1977;84(2):191-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ning Y, Wang Q, Ding Y, Zhao W, Jia Z, Wang B. Barriers and facilitators to physical activity participation in patients with head and neck cancer: a scoping review. Support Care Cancer. 2022;30(6):4591-4601. doi: 10.1007/s00520-022-06812-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Chan R, Yates P, McCarthy AL. Fatigue self-management behaviors in patients with advanced cancer: a prospective longitudinal survey. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2016;43:762-771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Noel CW, Du YJ, Baran E, et al. Enhancing outpatient symptom management in patients with head and neck cancer: a qualitative analysis. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2022;148(4):333-341. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2021.4555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kwong MH, Ho L, Li ASC, et al. Integrative oncology in cancer care—implementation factors: mixed-methods systematic review. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2023;14(1):183-199. doi: 10.1136/spcare-2022-004150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. van Dongen SI, de Nooijer K, Cramm JM, et al. Self-management of patients with advanced cancesr: a systematic review of experiences and attitudes. Palliat Med. 2020;34(2):160-178. doi: 10.1177/0269216319883976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Magalhães B, Fernandes C, Lima L, Martinez-Galiano JM, Santos C. Cancer patients’ experiences on self-management of chemotherapy treatment-related symptoms: a systematic review and thematic synthesis. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2020;49:101837. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2020.101837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bandura A. Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Educ Behav. 2004;31(2):143–164. doi: 10.1177/1090198104263660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hübner J, Welter S, Ciarlo G, Käsmann L, Ahmadi E, Keinki C. Patient activation, self-efficacy and usage of complementary and alternative medicine in cancer patients. Med Oncol. 2022;39:192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. White LL, Cohen MZ, Berger AM, Kupzyk KA, Swore-Fletcher BA, Bierman PJ. Perceived self-efficacy: a concept analysis for symptom management in patients with cancer. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2017;21(6):E272-E279. doi: 10.1188/17.CJON.E272-E279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hoffman AJ. Enhancing self-efficacy for optimized patient outcomes through the theory of symptom self-management. Cancer Nurs. 2013;36(1):E16-E26. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e31824a730a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Coolbrandt A, Dierckx de, Casterlé B, Wildiers H, et al. Dealing with chemotherapy-related symptoms at home: a qualitative study in adult patients with cancer. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2016;25:79-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Henneghan AM, Harrison T. Complementary and alternative medicine therapies as symptom management strategies for the late effects of breast cancer treatment. J Holist Nurs. 2015;33(1):84-97. doi: 10.1177/0898010114539191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Lopez G, Liu W, McQuade J, et al. Integrative oncology outpatient consultations: long-term effects on patient-reported symptoms and quality of life. J Cancer. 2017;8:1640-1646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Womack DM, Kennedy R, Chamberlin SR, Rademacher AL, Sliney CD. Patients’ lived experiences and recommendations for enhanced awareness and use of integrative oncology services in cancer care. Patient Educ Couns. 2022;105(7):2557-2561. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2021.11.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]