Abstract

Objectives:

Person-centered maternity care during childbirth is crucial for improving maternal and newborn health outcomes. Therefore, this study was aimed at assessing the determinants of person-centered maternity care in Central Ethiopia.

Methods:

An institutional-based cross-sectional study was conducted in public hospitals in Central Ethiopia from 30 January to 1 March 2023. A systematic random sampling technique was employed to enroll the study participants. Data were collected through face-to-face interviews using a structured questionnaire. After data collection, it was checked for completeness and consistency, then coded and entered into Epi Data version 4.4.2 and exported to SPSS version 26 for analysis. Both bivariate and multivariable logistic regressions were used to identify associated factors.

Results:

In this study, a total of 565 participants were involved, resulting in a response rate of 98.77%. The respondents mean score for person-centered maternity care was 60.2, with a 95% CI of (59.1, 62.3). No formal education (β = −2.00, 95% CI: −4.36, −0.69), fewer than four antenatal contacts (β = −4.3, 95% CI: −5.46, −2.37), being delivered at night (β = 2.20, 95% CI: 1.56, 6.45), and complications during delivery (β = −6.00, 95% CI: −9.2, −0.79) were factors significantly associated with lower person-centered maternity care.

Conclusion:

This study revealed that person-centered maternity care is low compared with other studies. Consequently, it is imperative to prioritize initiatives aimed at enhancing awareness among healthcare providers regarding the benchmarks and classifications of person-centered maternity care. Moreover, efforts should be directed toward fostering improved communication between care providers and clients, along with the implementation of robust monitoring and accountability mechanisms for healthcare workers to prevent instances of mistreatment during labor and childbirth.

Keywords: Person centered, maternity care, West Shewa, Central Ethiopia

Background

Globally, maternal and neonatal mortality remain substantial public health issues, with 287,000 maternal deaths during and following pregnancy and childbirth in 2020, alongside 2.3 million neonatal deaths in 2022.1,2 Ethiopia’s healthcare system has seen noteworthy advancements in reducing maternal mortality rates from 1140 deaths per 100,000 live births in 1990 to 401 deaths per 100,000 live births in 2017, yet substantial inequities in accessing quality maternal and neonatal care, especially in rural areas, remain persistent challenges. 3 Similarly, despite advancements in child health indicators, neonatal mortality remains a significant concern, with an estimated 27.13 deaths per 1000 live births in 2022. 4 These statistics underscore the ongoing importance of enhancing healthcare infrastructure, improving access to skilled birth attendants, and advocating for person-centered maternity care (PCMC) practices to combat maternal and newborn mortality.5,6

PCMC during childbirth is an essential component of maternal and newborn healthcare worldwide. 7 Defined as care that is respectful of and responsive to individual women and their preferences, needs, and values, PCMC ensures that women retain control over decisions regarding their care and treatment during childbirth.7,8 PCMC during childbirth comprises three domains of patient experience: namely respect and dignity, autonomy and communication, and supportive care.8,9 Improvements in the quality of care provided during childbirth have been linked to reductions in maternal and neonatal mortality and morbidity, and are needed to achieve global targets for maternal and newborn health. 10

Despite the recognized importance of PCMC during childbirth, studies have shown that many women worldwide still report negative experiences during childbirth.10,11 Globally one-third of women in high-income countries and up to two-thirds of women in low- and middle-income countries reported feeling unsupported, disrespected, or abused during childbirth. 11 In low-resource settings, where health systems are often under-resourced and understaffed, the provision of person-centered care can be particularly challenging. 12

In sub-Saharan Africa, the region with the highest burden of maternal and neonatal mortality, there has been a growing recognition of the importance of PCMC during childbirth. 13 However, the provision of such care remains inadequate. A systematic review study found that women in sub-Saharan Africa were less likely to receive PCMC during childbirth compared to women in other regions. 14 In Ethiopia, where maternal and neonatal mortality rates are among the highest in the world, the quality of maternal and newborn healthcare services has been identified as a priority area for improvement.15,16

Improving the provision of PCMC during childbirth in low-resource settings requires an understanding of the factors that affect the delivery of care.8,9 Previous studies conducted in Ethiopia revealed that lack of privacy, ineffective communication, understaffing, inadequate training, and negative attitudes among healthcare providers toward women during childbirth were associated with the delivery of substandard care.10,17,18 Further identifying the factors that affect the provision of PCMC during childbirth and understanding how best to address them is essential for improving maternal and newborn health outcomes. 19

The lack of PCMC during childbirth can lead to poor maternal and neonatal health outcomes, including increased risk of mortality and morbidity, and can also contribute to reluctance among women to seek care when needed. 18

Research on the determinants of person-centered care in Ethiopia is scarce, with no studies conducted in West Shewa. Previous research in Ethiopia has often been limited to single institutions. However, this study addresses this gap by including a wider range of health facilities, from primary hospitals to tertiary-level institutions. Therefore, this study aims to investigate the provision of PCMC during childbirth and its associated factors among mothers who gave birth at health facilities in West Shewa. The study employs the recently validated PCMC During Childbirth Scale, specifically designed for middle- and low-income countries.10,18,20,21

Methods and materials

Study design, area, and period

An institutional cross-sectional study was carried out in the West Shewa zone of Oromia regional state in central Ethiopia. The West Shewa zone is located in the Oromia Regional State, to the west of Ethiopia’s capital, Addis Ababa. Ambo, the capital city of the West Shewa zone, is located 114 km from Addis Ababa. The West Shewa zone has a population of 2,661,188, with 1,317,288 males and 1,343,900 females. The zone is home to eight hospitals and 90 health facilities that provide mother and child healthcare services.

There were eight hospitals offering maternal healthcare services, including Ambo General Hospital, Ambo University Referral Hospital, Gedo Hospital, Guder Hospital, Gindeberet Hospital, Inchinni Hospital, Bako Hospital, and Jeldu Hospital. The research took place from 30 January 2023 to 1 March 2023.

Population

All randomly selected women who gave birth at public hospitals in the West Shewa zone during the study period were included in this study. However, mothers who were referred to other health institutions before completing the service due to emergency conditions were excluded from the initial health institution during the study.

Sample size

The sample size for this study was determined using a single population proportion formula with the assumption of a standard normal distribution, a 95% confidence interval, a 5% margin of error, and a 65.8% proportion of PCMC during childbirth in selected public hospitals in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. 18

Considering a non-response rate of 10%, and 1.5 design effect, the final sample size was 572.

Where,

n = Minimum sample size required for the study.

Z = Standard normal distribution (Z = 1.96) with confidence interval of 95% and α = 0.05.

p = Proportion of PCMC during childbirth 65.8% in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

d = Absolute precision or tolerable margin of error (d) = 5% = 0.05.

Sampling procedures

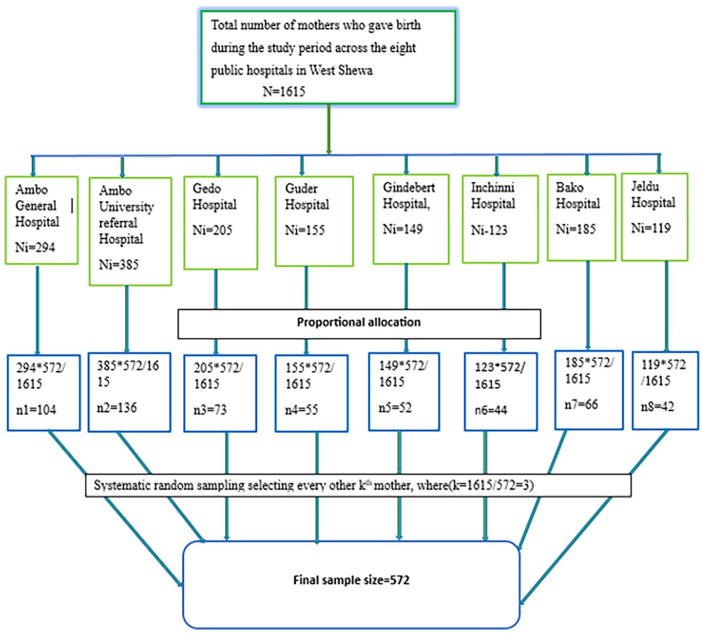

The study included all eight public hospitals in the West Shewa zone. The allocation of study participants was proportional, taking into account the patient flow for maternal healthcare services at each hospital over the previous 3 months, as shown in the figure below (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic presentation of sampling procedure for PCMC at in public health facilities in the West Shewa zone, Oromia region, central Ethiopia 2023 (n = 565).

Operational definitions

PCMC during childbirth

PCMC during childbirth is measured using the Person-centered care during childbirth scale, which has three domains: dignity and respect, communication and autonomy, supportive care, and 30 items with a four-point response scale. That is, 0 = no, never, 1 = yes, a few times, 2 = yes, most of the time, and 3 = yes, all the time.8–10,18 The scale score ranges from 0 to 90.

Dignity and respect

Measured by six items with each four-point response scale, that is, 0 = no, never, 1 = yes, a few times, 2 = yes, most of the time, and 3 = yes, all the time so, the total score ranges from 0 to 18.10,20

Communication and autonomy

Measured by using nine items with each item has a four-point response scale, that is, 0 = no, never, 1 = yes, a few times, 2 = yes, most of the time, and 3 = yes, all the time. So, the total score ranges from 0 to 27. 20

Supportive care

Measured by using 15 items with each item has a four-point response scale, that is, 0 = no, never, 1 = yes, a few times, 2 = yes, most of the time and 3 = yes, all the time. So, the total score ranges from 0 to 45.

The PCMC and sub-scales are categorized into “low, medium, and high.” Low scores are scores in the approximate lower 25th percentile, and high scores are in the 75th percentile.5,10

Complication during childbirth

Having at least one complication during childbirth, either on the mother or on the fetus, such as severe vaginal bleeding, convulsion, labor lasting more than 12 h, foul-smelling vaginal discharge, high fever, retained placenta, and fetal distress.22,23

Data collection tools, procedure, and quality control

The English version of the questionnaire was initially developed by reviewing various relevant literature studies conducted previously.5,10,11,17 Subsequently, it was translated into Afaan Oromo and then back to English by language experts to ensure consistency. The questionnaire encompassed socio-demographic information, obstetric history, health facility, and healthcare provider-related factors. Data were collected through face-to-face interviews using a structured, pre-tested Afaan Oromo version of the questionnaire from mothers who gave birth at public hospitals in the West Shewa zone. Six BSc midwifery professionals and three MSc graduates were recruited for data collection and supervision, respectively.

Data quality was assured during collection, coding, entry, and analysis. Two-day training was given for the data collectors and supervisors before actual data collection. The collected data were reviewed and checked for consistency, clarity; completeness, and accuracy throughout the data collection process by data collectors and supervisors. Furthermore, the pretest was done among 5% (29 of mothers) of the sample at Wolliso Hospital and the result was used to modify the tool.

Data processing and analysis

Both bivariate and multivariable logistic regressions were performed to identify significant predictors. PCMC was compared with socio-demographic, obstetric history, health facility, and healthcare provider-related factors. Those variables with p < 0.2 in bivariate analysis were considered for multivariable logistic regression analysis. Hosmer and Lemeshow goodness of fit tests were used to check model fitness before running the final model, which is 0.82. Finally, screened variables were fitted to the multivariable logistic regression model through a backward stepwise method to reduce the effects of the cofounders and identify the independent effects of each variable on the outcome variable. Finally, adjusted odds ratios with a 95% confidence interval were employed to declare strength, directions of the association of the predictors of PCMC, and a p-value of <0.05 was used to declare statistical significance.

Ethical approval and informed consent

The study was conducted in accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical clearance was obtained from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the College of Health Science and Referral Hospital, Ambo University, with a reference number of AU-CMHS/RCS/019/2015. A support letter was submitted to each hospital. Mothers provided written informed consent prior to the data collection process. Participants with no formal education were given written informed consent, which was obtained by taking their fingerprints after the interviewers read the consent form to them and agreed to participate. During the data collection process, the data collectors informed each study participant about the objective and anticipated benefits of the research project, and the study participants were also informed of their full right to refuse, withdraw, or completely reject part or all of their parts in the study. Data was collected anonymously and kept in lock with the investigators.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics

In this study, a total of 565 mothers completely responded, making the response rate 98.77%. The mean age of respondents was 26.5 years, with a standard deviation of 5 years. More than one-third of the 228 (40.3%) were in the age group of 18–24 years. The majority of respondents 319 (56.4%) were from rural residence. One-fourth of the respondents attended primary education 150 (26.5%). About 240 (42.4%) were farmers (Table 1).

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of mothers who gave birth at public health facilities in the West Shewa zone, Oromia region, central Ethiopia 2023 (n = 565).

| Characteristics | Categories | Number (N = 565) | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years | 18–24 | 228 | 40.3 |

| 25–29 | 211 | 37.3 | |

| More than 29 | 126 | 22.4 | |

| Marital status | Married | 546 | 96.6 |

| Other marital status a | 19 | 3.4 | |

| Religion | Orthodox | 224 | 39.7 |

| Protestant | 303 | 53.4 | |

| Muslim | 31 | 5.5 | |

| Other religion b | 7 | 1.4 | |

| Educational status | Unable to read and write | 85 | 15.2 |

| Able to read and write | 59 | 10.6 | |

| Primary education | 150 | 26.5 | |

| Secondary education | 133 | 23.5 | |

| College and above | 138 | 24.3 | |

| Mothers’ occupation | Government employee | 123 | 21.7 |

| Housewife | 202 | 35.6 | |

| Farmers | 85 | 15.0 | |

| Merchant | 78 | 13.8 | |

| Private employee | 66 | 11.6 | |

| Other occupation c | 13 | 2.3 | |

| Residence | Urban | 325 | 57.6 |

| Rural | 240 | 42.4 | |

| Monthly income | Less than 3000 | 293 | 51.9 |

| More than 3000 | 272 | 48.1 | |

| Mean = 3787.1 with SD of 3450.85 Ethiopian Birr, Median = 3000.00 | |||

Single, divorced, widowed.

Wakefata, Catholic.

Student, daily laborers.

Obstetric related factors

The mean and median number of parity among mothers was 2, with standard deviations of 2.17. More than one-third of the 229 (40.5%) mothers had given birth to 2 to 4 children. More than four-fifths of mothers, 465 (82.3%), had antenatal care follow-ups. Only a few mothers 59 (10.4%) had experienced obstetric complications during their current pregnancy. Of the total respondents, 451 (79.8%) gave birth by spontaneous vaginal delivery. More than half of the 289 (51.1%) mothers were delivered in the daytime, and 549 (97.1%) were live births (Table 2).

Table 2.

Obstetric characteristics of mother’s who gave birth at public health facilities in the West Shewa zone, Oromia region, central Ethiopia, 2023. (n = 565).

| Characteristics | Categories | Number | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current pregnancy intended/wanted | Yes | 506 | 89.4 |

| No | 59 | 10.6 | |

| Number of ANC follow ups contacts | No ANC follow up | 30 | 5.3 |

| Once to twice | 90 | 15.9 | |

| Three times | 175 | 31.0 | |

| Four and above | 269 | 47.8 | |

| Providers discussed about place of delivery during ANC | Yes | 462 | 81.5 |

| No | 74 | 13.2 | |

| No ANC follow up | 30 | 5.3 | |

| Discussed place of delivery with partner | Yes | 408 | 72.1 |

| No | 157 | 27.9 | |

| Labor started | Spontaneous | 525 | 92.8 |

| Induced | 40 | 7.2 | |

| Duration spent on labor | Less than 12 h | 415 | 73.4 |

| More than 12 h | 150 | 26.6 | |

| Total current stay at health facilities | 12 h or less | 276 | 48.9 |

| 13–24 h | 146 | 25.9 | |

| 25 h and above | 143 | 25.2 | |

| Mode of delivery | Spontaneous vaginal delivery | 452 | 79.9 |

| Assisted vaginal delivery | 44 | 7.9 | |

| Cesarean section | 69 | 12.2 | |

| Outcomes of delivery | Alive | 548 | 96.8 |

| Stillbirth | 17 | 3.2 | |

| Condition of mother during childbirth | No complication | 497 | 87.8 |

| Had complications | 68 | 12.2 | |

| Time of delivery | Day time | 300 | 53.1 |

| Nighttime | 265 | 46.9 | |

| Sex of provider | Male | 286 | 50.6 |

| Female | 279 | 49.4 | |

| Procedures done | Episiotomy | 141 | 25.0 |

| Fundal pressure | 64 | 11.5 | |

| Manual removal of placenta | 24 | 4.2 | |

| Instrumental delivery | 39 | 6.9 | |

| Cesarean section | 69 | 12.2 | |

| Asked your consent before performing procedure | Not asked me | 78 | 13.9 |

| Yes | 239 | 42.3 | |

| No procedure done for me | 248 | 43.7 | |

| Number of attendants during childbirth | One | 73 | 12.9 |

| Two | 240 | 42.3 | |

| Three | 111 | 19.6 | |

| Four and above | 143 | 25.2 | |

| Admitted to maternity waiting home before labor started | Yes | 31 | 5.6 |

| No | 534 | 94.4 |

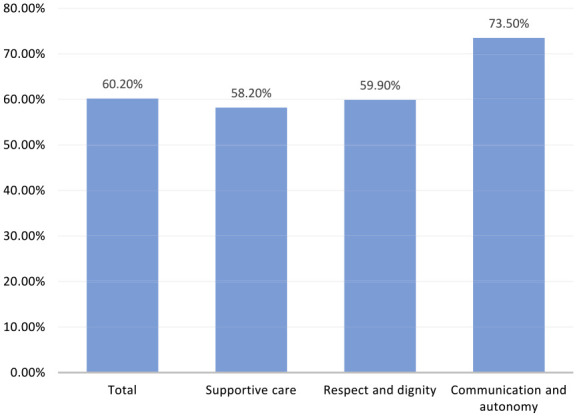

PCMC scales and sub-scales

The mean PCMC score of the respondents was 60.2 with the standard deviation 10.6 the minimum and maximum PCMC scores of 29 and 83, respectively (out of 90). The percentage mean PCMC score of the respondents was 63.8% (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Percentage means a score of person-centered care full scale and subscales from the total expected score among mothers who gave birth in at public health facilities in West Shewa zone, Oromia region, central Ethiopia, 2023.

Dignity and respect

The mean dignity and respect score of the respondents was 10.63 (SD = 2.83) from 18. More than one-third of the study participants, 190 (33.6%) were treated with respect, and only 169 (29.9%) were treated in a friendly manner during their stay in the facility. About 25 (4.4%) and 9 (1.6%) of mothers had experienced verbal or physical abuse at least a few times in the facility, respectively. In addition, 33 (5.8%) felt that their health information was not kept confidential (Table 3).

Table 3.

Distribution of dignity and respect at public health facilities in West Shewa zone, Oromia region, central Ethiopia, 2023 (n = 565).

| Items | No, never (%) | Yes, a few times (%) | Yes, most of the time (%) | Yes, all the time (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Providers treat me with respect | 8 (1.4) | 71 (12.6) | 296 (52.4) | 190 (33.6) |

| Provider treat me in a friendly manner | 31 (5.4) | 63 (11.2) | 302 (53.5) | 169 (29.9) |

| Providers shouted, insulted, scolded, threatened or talked me rudely (RC) | 529 (93.6) | 25 (4.4) | 9(1.6) | 2 (0.4) |

| Providers pushed, slapped, beaten, pinched or physically restrained (RC) | 559 (98.9) | 4 (0.73) | 2 (0.36) | 0 |

| People not involved in the care hear the discussion with the provider (RC) | 513 (90.8) | 13 (2.3) | 30(5.3) | 9 (1.5) |

| Feel health information was or will be kept confidential | 33 (5.8) | 14 (2.5) | 143 (25.2) | 375 (66.5) |

Communication and autonomy

The mean communication and autonomy score of the respondents was 19.85 (SD = 3.52) from 27. Most of the respondents 458 (81.1%) had reported that providers never introduced themselves. Of the total respondents, 191 (33.8%) of mothers reported that providers were never called by their name. Only 120 (21.3%) of respondents had been involved in decisions about their care during their stay in the facility. In addition, 43 (7.6%) of the respondents reported that providers never asked consent before doing examinations and procedures. The majority of study participants, 346 (61.2%) mothers, were not allowed to be in a position of choice during delivery. Only 23 (4.1%) and 34 (6%) of the respondents reported that the purpose of the examination, procedures, and medicines they took were explained to them, respectively, and 341 (60.3%) of respondents reported that they could ask any questions they had to healthcare providers most of the time (Table 4).

Table 4.

Distribution of communication and autonomy at public health facilities in West Shewa zone, Oromia region, central Ethiopia, 2023 (n = 565).

| Items | No, never (%) | Yes, a few times (%) | Yes, most of the time (%) | Yes, all the time (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Providers introduced themselves | 458 (81.1) | 61 (10.7) | 40 (7.1) | 6 (1.1) |

| Providers call me by my name | 191 (33.8) | 133 (23.5) | 171 (30.3) | 70 (12.3) |

| Involved in decisions | 31 (5.5) | 82 (14.5) | 332 (58.7) | 120 (21.3) |

| Consent before doing examinations and procedures | 43 (7.6) | 79(14) | 314 (55.6) | 129 (22.8) |

| Allowed position of choice | 346 (61.2) | 118 (20.9) | 90 (15.9) | 11 (2) |

| Providers speak in a language that I could understand | 8 (1.4) | 23 (40.1) | 154 (27.3) | 380 (67.2) |

| The purpose of examinations and procedures were explained | 23 (4.1) | 79 (14) | 329 (58.2) | 134 (23.7) |

| Purpose of medicines explained | 34 (6) | 68 (12) | 323 (57.2) | 140 (24.8) |

| I could ask any questions I had | 16 (2.8) | 117 (20.7) | 341 (60.3) | 91 (16.1) |

Supportive care

The mean supportive care score of respondents was 26.22 (SD = 4.67) from 45. Notably, a majority of respondents, comprising 293 (51.8%) and 469 (83%), respectively, reported not being allowed to have companions during labor and delivery. Among all respondents, 159 (28.2%) indicated that there were sufficient healthcare providers available. Additionally, a minority of mothers, specifically 30 (5.3%), perceived the rooms as crowded during their facility stay. Regarding facility amenities, over half of the participants (52.9%) reported the presence of water, while a significant majority (86.2%) confirmed the availability of electricity. Concerning waiting times, a substantial proportion (52.7%) experienced a little longer wait. However, only 64 (11.3%) mothers rated the general environment of the facility as very clean (Table 5).

Table 5.

Distribution of supportive care at public health facilities in West Shewa zone, Oromia region, central Ethiopia, 2023 (n = 565).

| Items | No, never (%) | Yes, a few times (%) | Yes, most of the time (%) | Yes, all the time (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allowed a labor companion | 293 (51.8) | 86 (15.3) | 105 (18.7) | 81 (14.2) |

| Allowed a delivery companion | 469 (83.0) | 43 (7.6) | 30 (5.3) | 23 (4.1) |

| Providers talk to me about my feeling | 33 (5.8) | 176 (31.2) | 319 (56.5) | 37 (6.5) |

| Providers supported anxieties and fears | 25 (4.4) | 110 (19.5) | 376 (66.6) | 54 (9.5) |

| Providers try to control when I have a pain | 10 (1.8) | 108 (19.1) | 378 (66.9) | 69 (12.2) |

| Providers paid attention when I need help | 9 (1.6) | 83 (14.7) | 363 (64.3) | 110 (19.4) |

| Providers took the best care for me | 15 (2.7) | 61 (10.8) | 312 (55.2) | 177 (31.3) |

| I trust providers regards to care | 7 (1.2) | 22 (4.0) | 123 (21.7) | 413 (73.1) |

| There were enough providers | 8 (1.4) | 44 (7.8) | 354 (62.6) | 159 (28.2) |

| The rooms were crowded (RC) | 149 (26.4) | 170 (30.1) | 216 (38.2) | 30 (5.3) |

| There was water in the facility | 57 (10.1) | 101 (17.9) | 108 (19.1) | 299 (52.9) |

| There was electricity in the facility | 4 (0.7) | 5 (0.9) | 75 (13.3) | 481 (85.1) |

| Feel safe in the facility | 2 (0.4) | 26(4.6) | 247 (43.7) | 290 (51.3) |

| Waiting time | Very long 20 (3.6) | Somewhat long 163 (28.8) | Little long 298 (52.7) | Very short 84 (14.9) |

| The general environment of the facility | Very dirty 0 | Dirty 19 (3.4) | Clean 482 (85.3) | Very clean 64 (11.3) |

Factors associated with PCMC during childbirth

The result of the bivariate analysis showed that the respondent’s educational status, number of ANC contacts, residence, presence of complications during delivery, presence of labor stimulation, newborn outcome, and time of delivery were significantly associated with lower PCMC during childbirth.

On multivariable logistic regression, educational status, the number of ANC contacts, the presence of complications during delivery, and the time of delivery were significantly associated with lower PCMC during childbirth at p-value less than 0.05.

The mothers who had no formal education had two times decreased PCMC during childbirth when compared to mothers with college and above level of education (β = −2.00, 95% CI: −4.36, −0.69). With a net of other factors, Mothers with less than four ANC contacts had 4.3 times (β = −4.3, 95% CI: −5.46, −2.37) decreased PCMC score as compared to mothers with four or more ANC contacts. Mothers who delivered during the day had 2.2 times increased PCMC score compared to those who delivered at night (β = 2.20, 95% CI: 1.56, 6.45). Mothers who experienced complications during delivery six times (β = −6.00, 95% CI: −9.2, −0.79) had lower PCMC scores than respondents who did not have complications (Table 6).

Table 6.

Multivariable linear regression analysis factors for Person-Centered Care during childbirth in at public health facilities in West Shewa zone, Oromia region, central Ethiopia, 2023 (n=565).

| Variable | Category | Unstandardized adjusted β coefficients | Standard error | 95% CI of β |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mothers’ education | No formal education | −2.00 | 1.68 | (−4.36, −0.69)* |

| Primary school | −.59 | 1.21 | (−3.25, −0.91) | |

| Secondary school | −.48 | 1.59 | (−3.51, 1.67) | |

| College and above | 0 | |||

| Number of ANC contacts | 1–3 | −4.3 | 0.97 | (−5.29, −2.26)* |

| 4 and above | 0 | |||

| Time of delivery | Night | 0 | ||

| Day | 2.2 | 0.81 | (1.56, 6.45)* | |

| Complication during delivery | No | 0 | ||

| Yes | −6.0 | 1.98 | (−9.2, −0.79)* |

CI: confidence interval; 0:reference. *Significant at p-value<0.001

Discussion

PCMC is recognized as the critical component of quality maternity care that contributes to better mother and newborn outcomes and promotes use of health services during labor and after delivery. 24 This study identified PCMC and factors associated with institutional-based childbirth in the West Shewa Zone at the health institution level. This study revealed that the mean score of person-centered care during childbirth was 60.2 with standard deviation (SD) ± 10.2. This result is relatively consistent with studies done in Kenya and the Ethiopian Amhara region, which showed that the mean score of person-centered care during childbirth was 60.2 and 58, respectively.20,21 The current finding showed that the mean score of person-centered care during childbirth was high compared to other studies.5,25 This variation might be due to the differences in the study setting and study population. Another study, the mean score of person-centered care during childbirth was high compared to a study conducted in the Sidama region of Hawassa City administration 56. 10 The reason for the high scale of person-centered care during childbirth in this study could be attributed to the COVID-19 pandemic resolution because the data for this study were collected after the pandemic effect of COVID-19, which may significantly affect the relationship between a care provider and mothers during childbirth as well as the quality of services.

The mothers who had no formal education had lower PCMC score during childbirth when compared to mothers with college and above level of education. This result is in agreement with studies done in India and Kenya showing that college-educated women have a higher PCMC score than non-educated women. 5 Another study done in Hawassa city administration also shows that mothers who didn’t get a formal education had decreased the person-centered care during childbirth. 10 The possible reason for this finding is that educated women tend to have better communication skills and can more easily grasp the circumstances in healthcare settings, allowing them to better recognize patient-centered care compared to less educated mothers. 26 Additionally, women’s education links to enhanced health-seeking habits through increased health awareness, financial independence, and the capacity to make proper health choices. 27

Mothers with less than four ANC contacts had lower PCMC score as compared to mothers with four or more contacts. This finding was in line with the study done in central Ethiopia. 18 This may be due to mothers who did not have complete ANC follow-up may have been unfamiliar with their healthcare providers, which could negatively impact PCMC. Furthermore, less frequent ANC checkups may have reduced the mothers’ use of maternal health services, affecting their interaction with healthcare providers. As a result, the mothers may have felt that they did not receive personalized, patient-focused care.

Mothers who delivered during the day had higher PCMC score compared to those who delivered at night. This was congruent with the findings of a research conducted in Dessie town. 21 A study done in Addis Ababa indicated that respondents night time delivery more likely had low person-centered maternity care. 18 This might be due to the fact that during day time there are more resources/infrastructures available and the number of health workers than at nighttime in which only one health worker might be assigned for duty in health centers and also very weak supervision from senior health workers and managers during nighttime.

Mothers who experienced complications during delivery had lower PCMC scores than respondents who did not have complications. This was consistent with study undertaken in Addis Ababa and Bahir Dar.18,28 The explanation for this could be that complications during childbirth heighten stress and anxiety for both mothers and healthcare providers, potentially impeding effective communication and shared decision-making, crucial aspects of PCMC. Complications may result in a loss of control for the mother over her birth experience, so this may lead to feelings of dissatisfaction and a perception of care that is not person-centered. Moreover, the need for medical interventions to manage complications may divert attention from the woman's preferences and needs, contributing to a perception of care that deviates from being person-centered for women experiencing complications during childbirth.

Limitation of study: While this study aimed to reduce recall bias by interviewing postpartum mothers right after delivery, it is still subject to social desirability bias. Some mothers may have reported more positive experiences with the services while still at the health facilities. The predominance of respondents from rural areas may limit the generalizability of the findings to urban populations. However, a strength of the study is that it covered many health facilities in the West Shewa zone, which serves over 2.5 million people.

Conclusion

The proportion of person-centered care during childbirth in the West Shewa zone was low compared with other studies done in low- and middle-income countries. Mother’s educational level, having fewer than four ANC follow-ups, nighttime delivery, and complications during childbirth were factors significantly associated with lower PCMC.

Therefore, health institutions and all other stakeholders should place due emphasis on creating awareness among care providers about the standards and categories of PCMC and emphatically consider those identified factors for intervention. Additionally, monitoring and reinforcing accountability mechanisms for health workers to avoid mistreatment and supporting them to provide the service with respect and compassion during labor and childbirth. Further research involving observation is also recommended to get more information about PCMC services.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-smo-10.1177_20503121241257790 for Person-centered maternity care during childbirth and associated factors at public hospitals in central Ethiopia by Wogene Daro Kabale, Gemechu Gelan Bekele, Dajane Negesse Gonfa and Amare Tesfaye Yami in SAGE Open Medicine

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Ambo University, College of Health Science and Referral Hospital for enabling us to conduct this study. The West Shewa zonal Health Office, study participants, data collectors, and supervisors have all been tremendously helpful.

Footnotes

Author’s contributions: WDK was involved in the project's conception and design. DNG assisted with data curation and supervision; ATY engaged in investigation and project administration; and WDK participated in writing up, reviewing, and editing the manuscript. All authors participated in funding acquisition, resource mobilization, and validation. WDK and GGB were involved in methodology and software and handled data analysis, interpretation, and writing the original draft. In addition, DNG contributed to the visualization. All of the authors agreed to submit to the current journal and gave final approval of the published version; they also solely agreed.

Data sharing statement: The datasets used or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethics approval: Ethical clearance was obtained from an Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the College of Health Science and Referral Hospital, Ambo University with reference number of AU-CMHS/RCS/019/2015*.

Informed consent: Mothers provided written informed consent prior to the data collecting process. Participants with no formal education were given written informed consent, which was obtained by taking their fingerprints after the interviewers read the consent form to them and agreed to participate.

Consent for publication: Not applicable.

Trial registration: Not applicable.

ORCID iDs: Wogene Daro Kabale  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6736-2805

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6736-2805

Gemechu Gelan Bekele  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8476-5320

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8476-5320

Dajane Negesse Gonfa  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7819-5504

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7819-5504

Amare Tesfaye Yami  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5901-1677

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5901-1677

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. World Health Organization. Trends in maternal mortality 2000 to 2020: estimates by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group and UNDESA/Population Division: executive summary. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 2. You D. Levels and trends in child mortality: report 2022. New York, NY: UNICEF, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Csace I. Ethiopia demographic and health survey 2016. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, and Rockville, Maryland, USA: CSA and ICF, 2016, pp. 1–551. [Google Scholar]

- 4. UNIGME. Levels and trends in child mortality: report 2023, estimates developed by the United Nations Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation. New York, NY: United Nations Children’s Fund, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Afulani PA, Feeser K, Sudhinaraset M, et al. Toward the development of a short multi-country person-centered maternity care scale. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2019; 146(1): 80–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. WHO, UNICEF.UNFPA, World Bank Group and the United Nations Population Division. Trends in maternal mortality 2000 to 2017: estimates by WHO, UNICEF. Geneva: UNFPA, World Bank Group and the United Nations Population Division, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Berwick DM. What “patient-centered” should mean: confessions of an extremist: a seasoned clinician and expert fears the loss of his humanity if he should become a patient. Health Aff 2009; 28(4): w555–w565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Afulani PA, Diamond-Smith N, Golub G, et al. Development of a tool to measure person-centered maternity care in developing settings: validation in a rural and urban Kenyan population. Reprod Health 2017; 14(1): 1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Afulani PA, Aborigo RA, Walker D, et al. Can an integrated obstetric emergency simulation training improve respectful maternity care? Results from a pilot study in Ghana. Birth 2019; 46(3): 523–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Getahun SA, Muluneh AA, Seneshaw WW, et al. Person-centered care during childbirth and associated factors among mothers who gave birth at health facilities in Hawassa city administration Sidama Region, Southern Ethiopia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2022; 22(1): 584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Abdel-Fattah M. Sociocultural dimensions to improve uptake of midwifery care in Morocco: a scoping review, http://hdl.handle.net/11375/26109(2020, accessed 11 May 2024).

- 12. Dutton J. What drives obstetric violence amongst nurses and midwives throughout the continuum of maternal health care in governmental hospitals and antenatal clinics in urban Western Cape (doctoral thesis).Cape Town: University of the Western Cape, Faculty of Community and Health Sciences, School of Public Health, 2022. http://hdl.handle.net/11394/9648.

- 13. Benova L, Owolabi O, Radovich E, et al. Provision of postpartum care to women giving birth in health facilities in sub-Saharan Africa: a cross-sectional study using demographic and health survey data from 33 countries. PLoS Med 2019; 16(10): e1002943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bohren MA, Vogel JP, Hunter EC, et al. The mistreatment of women during childbirth in health facilities globally: a mixed-methods systematic review. PLoS Med 2015; 12(6): e1001847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Austin A, Langer A, Salam RA, et al. Approaches to improve the quality of maternal and newborn health care: an overview of the evidence. Reprod Health 2014; 11(2): 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Birmeta K, Dibaba Y, Woldeyohannes D. Determinants of maternal health care utilization in Holeta town, central Ethiopia. BMC Health Serv Res 2013; 13(1): 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mengesha MB, Desta AG, Maeruf H, et al. Disrespect and abuse during childbirth in Ethiopia: a systematic review. BioMed Res Int 2020; 2020: 1237098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tarekegne AA, Giru BW, Mekonnen B. Person-centered maternity care during childbirth and associated factors at selected public hospitals in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2021: a cross-sectional study. Reprod Health 2022; 19(1): 199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Afulani PA, Kirumbi L, Lyndon A. What makes or mars the facility-based childbirth experience: thematic analysis of women’s childbirth experiences in western Kenya. Reprod Health 2017; 14(1): 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Afulani PA, Phillips B, Aborigo RA, et al. Person-centred maternity care in low-income and middle-income countries: analysis of data from Kenya, Ghana, and India. Lancet Glob Health 2019; 7(1): e96–e109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dagnaw FT, Tiruneh SA, Azanaw MM, et al. Determinants of person-centered maternity care at the selected health facilities of Dessie town, Northeastern, Ethiopia: community-based cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020; 20(1): 524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. World Health Organization. Reproductive Health and Research. Managing complications in pregnancy and childbirth: a guide for midwives and doctors. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gausia K, Ryder D, Ali M, et al. Obstetric complications and psychological well-being: experiences of Bangladeshi women during pregnancy and childbirth. J Health Popul Nutr 2012; 30(2): 172–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Oladapo OT, Tunçalp Ö, Bonet M, et al. WHO model of intrapartum care for a positive childbirth experience: transforming care of women and babies for improved health and wellbeing. BJOG 2018; 125(8): 918–922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ogbuabor DC, Nwankwor C. Perception of person-centred maternity care and its associated factors among post-partum women: evidence from a cross-sectional study in Enugu State, Nigeria. Int J Public Health 2021; 66: 612894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Oluoch-Aridi J, Afulani P, Makanga C, et al. Examining person-centered maternity care in a peri-urban setting in Embakasi, Nairobi, Kenya. PLoS One 2021; 16(10): e0257542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Watson HL, Downe S. Discrimination against childbearing Romani women in maternity care in Europe: a mixed-methods systematic review. Reprod Health 2017; 14(1): 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wassihun B, Zeleke S. Compassionate and respectful maternity care during facility based child birth and women’s intent to use maternity service in Bahir Dar, Ethiopia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2018; 18(1): 294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-smo-10.1177_20503121241257790 for Person-centered maternity care during childbirth and associated factors at public hospitals in central Ethiopia by Wogene Daro Kabale, Gemechu Gelan Bekele, Dajane Negesse Gonfa and Amare Tesfaye Yami in SAGE Open Medicine