Many doctors are concerned about their ability to take an appropriate history from a patient with a sexual problem. The main difference from an ordinary medical history is that the patient (and often the doctor) is commonly embarrassed and uncomfortable. Patients may feel ashamed or even humiliated at having to ask for help with a sexual problem that they think is private and that they should be able to cope with themselves. This is particularly so with men, especially young men, who have to admit to erectile dysfunction and therefore, as they see it, the loss of their masculinity. Some hospital doctors get over this initial difficulty by giving patients a preconsultation questionnaire. Many patients like this, but a substantial number dislike its anonymity and apparent coldness.

As with other history taking, the doctor must consider how to put the patient at ease, find out what the real problem is, discover the patient’s background and clinical history, and then work out a plan of management with the patient. The doctor should try to avoid showing embarrassment, especially if the patient wants to talk about things that are outside the doctor’s experience, as this can cause the patient to clam up.

Above all, there must be sufficient time allowed, and 45-60 minutes is an ideal that is unfortunately not often possible to achieve, although in general practice the patient can be asked to come back for a longer appointment at another time.

Making patients feel comfortable

If the doctor’s attitude is matter of fact, then the patient will relax and become matter of fact, too. It must be emphasised that, whatever the patient may admit to, the doctor must be non-judgmental.

A patient’s approach to the problem is often tentative and hidden by euphemism, with statements like “I think I need a check up” or “By the way, I have a [discharge, itch, soreness] down below.” These comments may well be slipped into a consultation about some other problem, and the doctor has to decide whether to compromise and try to investigate the matter immediately or persuade the patient to come back for a longer consultation.

Various interview techniques can be used to help patients relax more quickly; most are used by many doctors intuitively. These include the manner of greeting a patient, seeing that the patient is seated comfortably, and ensuring privacy (especially in a hospital clinic). If the seat is placed at the side of the desk, there is a greater opportunity to observe the patient’s body language, as well as this being a more friendly arrangement.

Useful observations on patients’ body language include

Their use of their hands and arms—such as uneasily twiddling with a ring, defensively crossing arms, or protectively holding a bag or briefcase on a lap

Pectoral flush, which creeps over the upper chest and neck (in some younger men as well as women) and which indicates unease despite outward appearance of calm

Body’s position in the chair—the depressed slump, tautly sitting bolt upright, or the relaxed sprawl

Postural echo, when doctor and patient sit in mirror images of each other’s position—adopted when there is harmony and empathy between the speakers

Finding out the problem

When people talk about embarrassing subjects, they are often vague and circumlocutory, and what they are trying to say must be clarified. Words such as “impotence,” for example, can mean different things to different men (and their partners), including failure to get an erection, failure to maintain an erection, and premature ejaculation, and, equally, a phrase such as “I’m sore down below” can mean anything from pruritus ani to some anatomical problem such as a prolapse or genital warts.

Careful and tactful elucidation is needed, and vagueness must be clarified. The questioner has to be particularly sharp in picking up what the patient is trying to say and be relaxed and unfazed by the subject matter, but this can be overdone.

A patient went back to a general practitioner’s receptionist to make a new appointment and said, “I don’t want to see him again. I only went in with a cold and he asked me all about my sex life.”

Very early in the discussion, the patient must be assured of complete confidentiality, particularly with practice and hospital clinic staff, and especially if personal secrets are disclosed, such as extra-marital affairs.

Factors to be noted during the interview include

The patient’s marital state

How many previous sexual partners there have been

Who the current partner is and for how long

How many children the patient has

Which of them lives with the patient

Whether there is obvious stress in the family

Whether there are financial worries.

Choice of terminology

One difficulty that bothers many doctors is whether to bring vernacular terms into the discussion because of their emotional charge, and some veer to using only medical terms. Patients too, because of embarrassment about using colloquialisms and fear of causing offence, may try to express their problem in medical terms but may well get the meaning wrong. Both can cause problems in getting an accurate history, but doctors must use very careful judgment in deciding if it would be more appropriate to use the language of the streets.

Although there are frank articles in many magazines and newspapers, many patients, especially younger women, still will not know the meaning of “orgasm” but will understand “come.” Fellatio and cunnilingus are not words in general use, and use of the street versions would assume a very relaxed and empathic discussion, but “oral sex” is acceptable to men and women of all ages as an alternative. Usually, the line is very fine and is often related to age and gender.

Open questions

The way open and closed questions are used in history taking is crucial. A closed question expects a specific reply, such as “Yes” or “No,” and is characteristic of the medical model of history taking, such as: “Have you had this problem before? Does it hurt when you pass water? Did you practise safe sex?”

A 16 year old boy was struggling to find medical words to explain his anxieties about masturbation and ejaculation. When the doctor tried to help him out by using colloquial terms the boy looked startled and then grinned and said, “I didn’t know doctors knew those words.” The rest of the consultation was much more relaxed and informative

Starting with an open question—“How can I help you?”— and continuing with open questions—“What’s the problem?” or “What do you think caused the difficulty?”—gives patients an opportunity to expand and to say what is really bothering them. Many younger doctors are worried that a garrulous person might get out of hand, but remaining in control is a skill a good interviewer learns quickly. Judgmental questions—“Don’t you think you’re past that sort of thing now?”—should be avoided.

Silence

Silence is a powerful tool in taking a good history, and the best interviewers—whether on the radio, on television, or in the consulting room—have realised this. However, many doctors find it extremely difficult not to end a silence, speaking prematurely because they are embarrassed by the quiet or feel that it is rude not to say anything, whereas the patient is often using the time to order his or her thoughts. Valuable details may be lost if those thoughts are cut across by an inappropriate statement from the doctor. The rule is, have patience.

Example of using repetition to elicit information

“Doctor, I think I need a check up”

“Yes, of course. It’s quite a time since the last one. Let me start with your blood pressure....”

Compare this with

“Doctor, I think I need a check up”

“Check up?”

“Yes, I’m not performing as well as I used to”

“Performing?”

“Yes, well, you know, I think I’m impotent. My wife is very good about it and doesn’t complain, but I feel so guilty and ashamed”

“Ashamed?”

“I feel terrible. I don’t feel a man any more, especially as we used to have such a good sex life ....”

Repetition

Repetition of the last word or phrase, especially if it is one which is emotionally loaded, is a powerful technique to get a patient to elaborate on what he or she is trying to say. Everyone uses this technique, often without thinking, but when it is used deliberately without overtones—although it may seem artificial and forced—it can elicit much information.

Content of a sexual history

Although a joint interview is always much more valuable, patients often prefer to discuss things alone in the first instance. A warm invitation for the partner, coupled with the observation that a sexual problem is not the patient’s problem alone, can put the patient’s anxieties into perspective.

Questions to be asked in sexual history

The problem as the patient sees it

How long has the problem been present?

Is the problem related to the time, place, or partner?

Is there a loss of sex drive or dislike of sexual contact?

Are there problems in the relationship?

What are the stress factors as seen by the patient and by the partner?

Is there other anxiety, guilt, or anger not expressed?

Are there physical problems such as pain felt by either partner?

To be complete, the history must include several factors.

Social history

A detailed social history helps to put the patient into context. The patient’s problem can be the first item to be discussed, but taking a social and medical history before exploring the problem allows the patient time to relax while talking about familiar things such as children, home, and job and enables the doctor to put the problems into perspective. Even if the doctor is the patient’s general practitioner and knows him or her well, a review of the social history will give a valuable updating and incidental information that is often highly relevant.

Medical history

It used to be thought that all sexual problems, especially erectile dysfunction, were psychogenic in origin. General opinion has shifted to accepting that a large proportion can have a physical basis, though, not surprisingly, often with a psychogenic overlay. It is therefore important to take a detailed medical history, particularly bearing in mind those illnesses that may affect sexual performance.

Diabetes can eventually cause impotence in up to half of affected men.

Depression and psychotic illnesses cause loss of sexual desire (but not necessarily loss of function) in a high proportion of both men and women, but careful questioning is needed to elicit them. Altered sleep pattern is a valuable indicator of depression.

Heart disease, especially when combined with hyperlipidaemia and arteriopathy, accounts for erectile dysfunction in many men.

Other hormone deficiencies, especially thyroid and testosterone, reduce sexual desire and performance in both sexes.

Operations and trauma, especially gynaecological and prostate, can cause problems. Damage to the pelvis or spine is another obvious cause.

Prolactinoma may, rarely, present as a loss of sexual desire and headaches in a younger man.

Pain—of arthritis, vaginal atrophy in the older woman, or a phimosis—can be very offputting to one or other partner.

Patient’s (and partner’s) view of the problem

Marital dysfunction or just plain sexual boredom after many years of being together can be a major cause of impotence. It is useful to try to assess a couple’s relationship just by looking at their body language to each other.

Commonly prescribed drugs associated with sexual dysfunction (list not fully comprehensive)

| Drug | Erectile dysfunction | Altered drive | Ejaculatory disorder | Orgasmic disorder | Priapism |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anticonvulsants | |||||

| Carbamazepine | ✓ | ||||

| Phenytoin | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Primidone | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Antidepressants | |||||

| Tricyclics | |||||

| Amitriptyline | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Amoxapine | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Clomipramine | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Imipramine | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Maprotiline | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Nortriptyline | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Protriptyline | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Monoamine oxidase inhibitors | |||||

| Phenelzine | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors | |||||

| Fluoxetine | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Fluvoxamine | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Paroxetine | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Sertraline | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Antipsychotics | |||||

| Chlorpromazine | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Fluphenazine | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Haloperidol | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Thioridazine | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Benzodiazepines | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Antihypertensives | |||||

| Atenolol | ✓ | ||||

| Clonidine | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Guanethidine | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Hydralazine | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Labetalol | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Methyldopa | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Metoprolol | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Pindolol | ✓ | ||||

| Prazosin | ✓ | ||||

| Propranolol | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Reserpine | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Timolol | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Verapamil | ✓ | ||||

| Diuretics | |||||

| Amiloride | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Chlorthalidone | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Indapamide | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Spironolactone | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Thiazides | ✓ | ||||

| Antiemetics | |||||

| Metoclopramide | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs | |||||

| Naproxen | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Anticholinergics | |||||

| Atropine | ✓ | ||||

| Diphenhydramine | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Hydroxyzine | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Propantheline | ✓ | ||||

| Scopolamine | ✓ | ||||

| Antispasmodics | |||||

| Baclofen | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Hypnotics | |||||

| Barbiturates | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

In men with erectile dysfunction it is helpful to know the patient’s, and especially his partner’s, views of the causes as this often reveals their anxieties about other problems, including malignancy. It is also useful to know the speed of onset: organic causes such as diabetes tend to develop slowly whereas psychogenic ones appear more rapidly, but this guide is not infallible. A psychogenic content to the problem is indicated if the man gets erections during the night or on early waking or if he can masturbate successfully—although many are reluctant to admit this in front of their partner. (Erectile dysfunction is covered in a later article in this series.)

Strict upbringing and religious beliefs, especially if there is disparity between the partners as in mixed marriages, can often have a devastating effect on a sexual relationship. Other questions to consider include whether unemployment or the threat of it is causing anxiety, or whether retirement is causing a loss of self esteem in either the patient or partner, with concomitant effects on sexual performance. Has the menopause or a hysterectomy changed the way a woman perceives herself? Does she feel less feminine or attractive to her partner, or has her sex drive increased with freedom from child rearing, causing disparity between the couple’s sexual desires and needs?

These aspects may need very tactful questioning to elicit and require sensitivity on the part of the doctor..

Medical and recreational drugs

Many drugs, especially hypotensives, and the quantity and frequency of alcohol and nicotine intake, can have a profound effect on sexual performance, as can many “cold cures” and over the counter hypnotics that contain anticholinergics such as diphenhydramine. Equally, the lack of hormone replacement therapy can cause a major problem in a menopausal woman’s sexual relationship, with vaginal atrophy and dryness leading to pain during sexual intercourse. This may not be volunteered by, or even be apparent to, her partner and is a good reason to try to listen to the couple together.

Cannabis can cause an initial euphoria, improving sexual confidence, but, like alcohol, it can greatly diminish ability. Other drugs, including the so called hard drugs, have a deleterious long term effect.

Further reading

Morris D. Man watching. London: Triad Granada, 1980

Bancroft J. Human sexuality and its problems. 3rd ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1998

Gregoire A, Prior J. Impotence, an integrated approach to clinical practice. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1993

Agreeing a management plan

The final part of history taking is for the doctor to decide what is to be done next. A management plan should then be discussed and agreed with the patient. At this point they should decide whether the patient’s partner should be invited for a joint meeting if he or she has not been present. In this way, the patient will feel that a partnership exists with the doctor, and treatment is much more likely to succeed.

Figure.

Placing seats at the side of the desk is a more friendly arrangement for an interview and makes it easier to observe a couple’s body language to each other, which gives clues to their relationship. (Reproduced with subjects’ permission)

Figure.

Patients’ body language, such as defensively crossing arms, can reveal their state of mind

Figure.

Postural echo, when doctor and patient sit in mirror images of each other’s position, indicates empathy between the speakers

Figure.

Phrases such as “I’m sore down below” can mean anything from minor irritation to an anatomical problem such as rectal prolapse

Figure.

Doctors must use very careful judgment in deciding if it would be appropriate to use colloquialisms when discussing a sexual problem

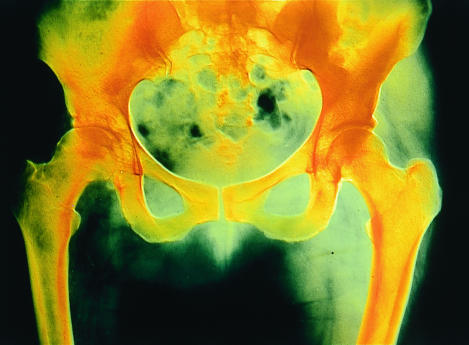

Figure.

Painful osteoarthritis of the hips or knees limiting movement can be very inhibiting for sexual activity

Acknowledgments

The pictures of defensive body posture and postural echo are reproduced with permission of Mike Wyndham. The picture of rectal prolapse, by Dr P Marazzi, and the x ray of an arthritic hip joint, by CRNI, are reproduced with permission of Science Photo Library.

Footnotes

John Tomlinson is physician at the Men’s Health Clinic, Winchester and London Bridge Hospital, and formerly general practitioner in Alton and honorary senior lecturer in primary care at University of Southampton.

The ABC of sexual health is edited by John Tomlinson.