Highlights

-

•

Essential oils: aromatic fluids for diverse food, pharma, and cosmetics use.

-

•

EOs are obtained from various plant materials.

-

•

Ultrasound-assisted extraction alone or in combination with other techniques is effective.

-

•

Ultrasound has several limitations, which have been addressed as well.

Keywords: Ultrasound assisted extraction, Essential oils, Plant materials, Extraction yield, Industrial applications

Abstract

Ultrasound-assisted extraction (UAE) is an innovative process for recovering valuable substances and compounds from plants and various biomaterials. This technology holds promise for resource recovery while maintaining the quality of the extracted products. The review comprehensively discusses UAE’s mechanism, applications, advantages, and limitations, focusing on extracting essential oils (EOs) from diverse terrestrial plant materials. These oils exhibit preservation, flavor enhancement, antimicrobial action, antioxidant effects, and anti-inflammatory benefits due to the diverse range of specific compounds in their composition. Conventional extraction techniques have been traditionally employed, and their limitations have prompted the introduction of novel extraction methods. Therefore, the review emphasizes that the use of UAE, alone or in combination with other cutting-edge technologies, can enhance the extraction of EOs. By promoting resource recovery, reduced energy consumption, and minimal solvent use, UAE paves the way for a more sustainable approach to harnessing the valuable properties of EOs. With its diverse applications in food, pharmaceuticals, and other industries, further research into UAE and its synergies with other cutting-edge technologies is required to unlock its full potential in sustainable resource recovery and product quality preservation.

1. Introduction

In the 21st century, an obvious shift has been observed as humans increasingly shifting from synthetic hazardous substances to their natural counterparts. Numerous substances from biological origins are being employed within various industries, particularly in the food and pharmaceutical sectors. A notable example of such invaluable substances is EOs. These are volatile, concentrated liquids primarily comprised of diverse compounds, including terpenes, aldehydes, ketones, alcohols, esters, and oxides [1], [2], [3], [4]. The secondary metabolites of plants are mainly derived from various plant materials, encompassing leaves, peels, seeds, flowers, barks, fruits, stems, and roots [5], [6], [7]. EOs have strong and pleasant smells because of their aromatic nature, distinguishing fragrances and scents for plants [8], [9], [10]. These EOs find applications in food, pharmaceuticals, and cosmetics due to their preservative, flavoring, antimicrobial, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-cancerous, and anti-septic properties [11], [12], [13]. In 2021, the global market for EOs reached a valuation of USD 8.74 billion. Projections indicate that the EOs market is anticipated to experience an annual growth rate of 9.5 %, expanding from USD 9 billion in 2021 to USD 18 billion by 2028, covering the estimated period from 2021 to 2028 [14], [15], [16]. Nevertheless, EOs present challenges due to their intense fragrance, high reactivity, hydrophobic nature, limited solubility, and incompatible interaction with fats, carbohydrates, and proteins in food. These characteristics constrain their widespread application. Therefore, exploring innovative approaches, such as encapsulation, emulsification, dilution, and blending, is imperative to improve the practicality of using EOs on a larger scale [17], [18].

Extraction is a significant process of extracting these valuable substances from plant matrices. It is crucial to obtain high-yield and good-quality EOs at low cost. Numerous conventional techniques are being employed for recovering the EOs from plant materials, such as cold press [19], [20], [21], distillation (water, steam/water, and steam) [4], [22], solvent extraction [23], [24], maceration and leaching [25]. Fig. 1 shows commonly used conventional techniques for the extraction of EOs. Traditional extraction practices suffer from significant shortcomings, including insufficient yield, excessive energy demands, prolonged processing durations, high cost, persistent challenge of residual organic solvents, and elevated temperatures employed during the process that can negatively alter the composition of EOs [2], [26], [27]. Furthermore, the inherent scarcity of EOs within plant materials necessitates high-performance extraction techniques to maximize their recovery. This resonates with the current focus on highly efficient, eco-friendly, and sustainable extraction methods, which offer promising alternatives to traditional approaches [25], [28], [29]. Driven by these challenges, the global EOs industry has shifted its focus toward developing cutting-edge, sustainable, and environmentally friendly technologies for EOs extraction. This paradigm shift has paved the way for the proliferation of innovative techniques like UAE, SFE, EAM, MAE, SWE, and PHWE [21], [30].

Fig. 1.

The extraction of essential oils from various plant materials by the application of conventional extraction techniques.

One of these emerging green technologies is ultrasound, a versatile and non-invasive approach with various applications such as extraction, homogenization, microbial disinfection, degassing, emulsification, drying, thawing, and freezing. The extraction process facilitated by ultrasound is known as UAE, the core of which lies in the propagation of ultrasound waves through the extraction medium [31], [32]. These inaudible sound waves, with frequencies exceeding human hearing (>20 kHz), generate alternating zones of compression and rarefaction. This microscopic energy creates intense turbulence within the medium, acting like a microscopic mixer to bring the solvent and plant material into close contact. Mass transfer unfolds in two distinct phases: Initially, the tissue layer undergoes an explosive transformation, followed by the propagation of waves that drive mass transfer into the solvent. The efficiency of this process escalates with higher power and prolonged application time [25], [33]. This enhanced mass transfer facilitates the efficient extraction of sensitive EOs while minimizing solvent requirements, rapid isolation, and high quality [34], [35]. To elevate the performance of the UAE, its application can be synergistically combined with temperature and pressure control. This strategic interplay amplifies the extraction process, unlocking even greater yields and efficiency [4], [36]. This review provides a comprehensive overview of EOs extraction from various plant materials by applying ultrasound as a pretreatment, as a standalone method throughout the entire extraction process, or in conjunction with conventional and innovative techniques. It critically reviews the mechanism, limitations, latest advancements, and perspectives in applying UAE in EOs extraction.

2. Essential oils (EOs)

2.1. Composition

EOs are complex mixtures of bioactive compounds synthesized in the cytoplasm and plastids of plant cells through various mechanisms. The composition of EOs can vary significantly based on the plant material and species from which they are derived. GC–MS analysis is commonly employed to analyze EOs, providing insights into the composition and structures of the compounds present. Out of the approximately 3000 EOs produced by various plants, around 300 have significant applications in multiple fields. [37], [38]. These EOs comprise about 300 different compounds, primarily volatile organic compounds. These compounds are broadly categorized into two groups: terpenoids and non-terpenoids. Terpenoids, formed by the combination of two (monoterpene), three (sesquiterpene), or four (diterpene) isoprene units, and phenylpropanoids, representing non-terpenoid hydrocarbons, constitute the two main structural classes of phenolic chemicals that serve as the principal constituents. [15], [39]. The other compounds present in EOs include oxides (linalool oxide and cineol), esters (eugenol acetate and linalyl acetate), aldehydes, ketones, and alcohols. [40]. Fig. 2 explains the composition of EOs.

Fig. 2.

Composition of essential oils.

Peels of fruits are rich sources of EOs like OPEOs containing a substantial quantity of compound limonene, which falls in the category of terpenes. Additional compounds present in OPEOs encompass linalool, α-terpineol, and myrcene. These identical compounds, with some variations, were also identified in SLEOs [41], [42]. Limonene is citrus EOs principal compound, followed by β-myrcene and L-carvone [43]. It is also the major compound of EOs obtained from celery seeds [44], [45]. Carvone, dihydro carvone, and dill apiol were the main compounds found in the EOs of dill seeds [25]. In the EOs obtained from flowers of Jitsugetsu Nishiki, a total of 51 compounds were identified,d and the primary constituents included 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene, tricosane, nerol, and others [46]. The EOs extracted from Paeonia frutescens leaves comprise perilla ketone, constituting 74 % of the total components. Other significant compounds identified include linalool, β-caryophyllene, apiol, caryophyllene oxide, and more [47], [48]. The EOs derived from tarragon leaves encompass a variety of compounds, including limonene, sabinene, estragole, β-pinene, geranyl acetate, methyl eugenol, and others [26], [49]. The cinnamon EOs were rich in one compound known as trans-cinnamaldehyde [2]. These examples highlight the diverse compositions of EOs obtained from various plant materials. Table 1 likely provides additional information on the identified compositions of EOs from different sources. The extraction method affects the composition of obtained EOs because of oxidation, reduction, and hydrolysis that occur during the extraction process.

Table 1.

Composition of essential oils of various plant materials.

| Plant name | Plant material | Composition of Essential oil | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perilla frutescens (L.) Britt. | Leaves | Linalool | [47] |

| Carvone | |||

| Perilla ketone | |||

| β-Caryophyllene | |||

| Apiol | |||

| Ocimum plant (Ocimum bacilicum) | Leaves | Eugenol | [50], [30] |

| Camphor | |||

| Estragole | |||

| Linalool | |||

| Methyl eugenol | |||

| Lemon verbena (Aloysia citriodora) | Leaves | Sabinene | [30] |

| Linalool | |||

| α-pinene | |||

| Thymol | |||

| 1,8-cineole | |||

| Tarragon (Artemisia dracunculus L.) | Leaves | Sabinene | [26] |

| β-pinene | |||

| Limonene | |||

| (Z)-β-ocimen | |||

| (E)-β-ocimen, | |||

| Geranyl acetate | |||

| Beefsteak plant (Perilla frutescens) | Leaves | Limonene | [33] |

| Farnesene | |||

| Caryophyllene | |||

| Perillaldehyde | |||

| Betel leaf (Piper betle L.) | Leaves | Indane | [34] |

| Hydrindane | |||

| Copaene | |||

| Perillae folium (Perilla frutescens L.) | Leaves | Monoterpene glycosides | [35] |

| Tocopherols | |||

| Anthocyanins | |||

| Triterpenes | |||

| Ursolic acid | |||

| Rosmarinic acid | |||

| Bitter orange (Citrus aurantium) | Peel | Limonene | [25] |

| Linalool | |||

| Myrcene | |||

| Terpineol | |||

| Sweet lime (Citrus limetta) | Peel | Bergamol | [43] |

| β-pinene | |||

| α-pinene | |||

| 1,8 cineole | |||

| Linalool | |||

| Sweet orange (Citrus sinensis) | Peel | Limonene | [51] |

| β-myrcene | |||

| α-pinene | |||

| Citrus (Tribute citrus) | Peel | α-pinene | [6] |

| β-phellandrene | |||

| γ-myrcene | |||

| Sabinene | |||

| D-Limonene | |||

| Rough lemon (Citrus jambhiri) | Peel | 1,7,7-trimethyl-2-norbornene | [4] |

| Beta-bisabolene | |||

| Beta-myrcene | |||

| Neryl acetate | |||

| Sabinene | |||

| Carrot (Daucus carota) | Seeds | Carotol | [52] |

| Sabinene | |||

| α-pinene | |||

| Daucol | |||

| Celery (Apium graveolens L.) | Seeds | Limonene | [45] |

| Selinene | |||

| Sedanenolid | |||

| 3-butylphtalide | |||

| α-selinene | |||

| Dill (Anethum graveolens L.) | Seeds | Limonene | [25] |

| dill Apiole | |||

| α-Phellandrene | |||

| dihydrocarvone | |||

| Cardamom (Elettaria cardamomum) | Seeds | 1,8 cineole | [53] |

| Dihydrocarveol | |||

| E-nerolidol | |||

| Terpinen-4-ol | |||

| Geraniol | |||

| Oiiveria decumbens (Carum orientalum) | Fruit | Thymol | [54] |

| Carvacrol | |||

| Myristicin | |||

| ρ-cymene | |||

| γ-terpinene | |||

| Five-flavor berry (Schhisandra chinensis) | Flower | Ylangene | [55] |

| α-bergamotene | |||

| β-himachalene | |||

| Sweet cherry (Prunus avium L.) | Flower | Olefins | [56] |

| Beta-pinene, | |||

| Trans-beta-ocimene | |||

| β-ocimene | |||

| White and black peppers (Piper nigrum L.) | Fruit | δ-elemene | [57] |

| Caryophyllene | |||

| Limonene | |||

| β-pinene | |||

| α-copaene | |||

| Cinnamon (Cinnamomum cassia) | Bark | trans-cinnamaldehyde | [2] |

| 2-methoxycinnamaldehyde | |||

| Copaene | |||

| Clove (Syzygium aromaticum) | Buds | β-caryophyllene | [58] |

| Eugenyl acetate | |||

| Eugenol | |||

| α-humulene | |||

| Caryophyllene oxide |

2.2. Mechanism

The noteworthy properties such as flavor enhancement, preservative action, antibacterial, antifungal, and antioxidant effects attributed to these EOs stem from the presence of the compounds mentioned above. These properties have led to the widespread application of EOs in food, medicine, and agriculture. While elucidating the mechanisms behind these properties is challenging, numerous researchers have endeavored to explore and expound upon these mechanisms [6], [15], [59]. The evaluation of EO antibacterial activity predominantly relies on two key methods: MIC and the measurement of the zone of inhibition (mm) in the agar-well diffusion technique [50]. Damyeh et al. [60] found that EOs extracted from P. ferulacea leaves demonstrated antibacterial activity at 10 μL concentration. This was evident when measuring inhibition zones, ranging from 10.00 to 16.83. Radünz et al. [61] studied that applying thyme EOs as a spray on hamburgers effectively inhibited the growth of various bacteria, including E. coli, S. aureus, and others, for up to 14 days. The antibacterial activity of EOs is attributed to cytoplasmic membrane disruption of bacteria because of lipophilic components present in the oil. It leads to the structural damage of the entire cell [4], [62]. It causes the disturbance of essential life processes such as processing nutrients, synthesizing macromolecules, producing energy, and transporting growth regulators [42].

EOs antifungal activity is similar to its antibacterial activity described before [63]. He et al. [64] explained that EOs of Perilla frutescens rhizome destroyed cell walls and interfered with the morphology of the fungus Aspergillus flavus, leading to a notable reduction in its growth. D’Arrigo et al. [62] assessed the pistachio hull's EOs activity against C. albicans, C. parapsiloss, and C. glabrata. The EOs exhibited inhibitory effects on the growth of all these strains, achieving complete inhibition within the concentration range of 1.25 mg/mL to 5.0 mg/mL. In a study by Restuccia et al. [65], the effect of five different citrus EOs on the inhibition of growth and toxin production of A. flavus was evaluated. These EOs (0.5 – 2 % concentration) proved to be very effective in preventing fungal attack by causing over 90 % reduction in mycelial growth. It was found that the primary cause of EOs antifungal activity is their ability to induce depolarization and alter fungal cell membranes chemically or physically, compromising the fungi's ability to synthesize and perform metabolic processes. These effects likely impact hyphae/mycelial growth and morphogenesis, leading to an antifungal outcome [66]. Moreover, terpenoids with lipophilic nature present in most EOs disrupt the cell membrane or damage mitochondria, causing cell death and inhibiting fungal growth [65], [67], [68], [69], [70]. Free radicals are unstable molecules characterized by unpaired electrons, posing a threat to cellular structures as they can cause damage. EOs contain antioxidants (polyphenolic compounds) that neutralize these free radicals. Antioxidants in EOs achieve this by donating electrons or hydrogen atoms, thereby preventing oxidative stress and mitigating potential damage to cells [71], [72], [73]. Priyadarshi et al. [4] showed that independent of the concentration applied, the EOs extracted from the leaves of A. citriodora effectively scavenged free radicals. Ilić et al. [70] recovered the EOs from various plant species grown in Serbia and determined their antioxidant activity by FRAP test. The IC50 values ranging between 6.15–6.78 μg/mL confirmed the strong antioxidant potential of these EOs. Similarly, Wan et al. [73] obtained IC50 values of 22 mg/L of EOs from the citrus fruit kumquat peelat.

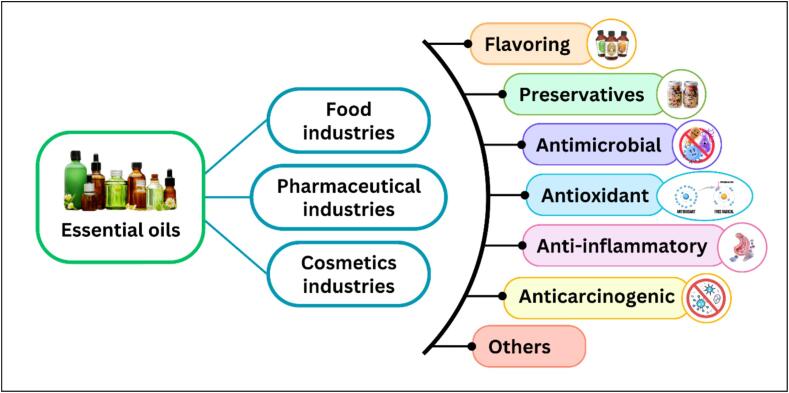

2.3. Applications

The EOs are currently being used in immense quantities in various industries because of the diverse range of compounds found in mainly utilized in the food, pharmaceutical, and cosmetics industries because of their unique multidimensional properties. In the food industry, EOs see diverse applications, serving as flavoring agents, acting as preservatives, contributing to aromatherapy in food, participating in the preparation of functional foods, enhancing the production of flavored beverages, and serving as active agents in packaging materials [24], [74]. In the pharmaceutical industry, these are utilized as herbal and drug enhancers. In the cosmetics industry, EOs play a role as fragrance components in perfumes, contribute to aromatherapy in skincare, and are incorporated into various products such as lip balms, massage oils, skincare products, and hair care products. EOs' versatility makes them valuable in these sectors, adding a wide range of flavor, aroma, and therapeutic properties to products [6], [53]. Fig. 3 shows the multiple applications of EOs.

Fig. 3.

Application of essential oils in various industries.

In food industries, the EOs obtained from waste peels (orange, lemon, grapefruit) are utilized in baked products (biscuits, bread, cakes, cookies), ice-creams, gelatin, sweets, and marmalades. These are also used in formulations of various medicines [10], [21], [42], [75]. Like waste peels, the EOs derived from leaves (mint, eucalyptus, etc.) of various plant species are also used in baked foods, sweets, beverages, and dairy products worldwide [47]. Moreover, the EOs extracted from stems, roots, and barks have applications as additives in several food product developments [52]. Besides its use in the food industry, EOs obtained from peel waste (citrus) are effectively used in pharmaceutical industries. The compound limonene, present abundantly in citrus EOs, exhibited significant antiulcerogenic and gastro-protective activities that can be considered a promising pharmaceutical agent for preventing gastric ulcers [42]. EOs are employed not only to mask certain drugs' bitter and unpleasant taste but also for their antibacterial and anti-inflammatory effects [21], [76]. The EOs derived from seeds (carrot, celery, coriandtc) exhibit a protective anticonvulsant impact in strychnine and metrazol poisonings cases. These oils are also used as a diuretic and stomachic for medical purposes. Furthermore, they are claimed to possess hepatocellular regenerative properties, serving as a general tonic and stimulant as a cicatrizant [52]. EOs extracted from flowers (lavender, rose, chamomile, jasmic.) are widely utilized in the fragrance industry and aromatherapy because of their pleasant fragrances [46].

3. Ultrasound-assisted extraction (UAE) of EOs

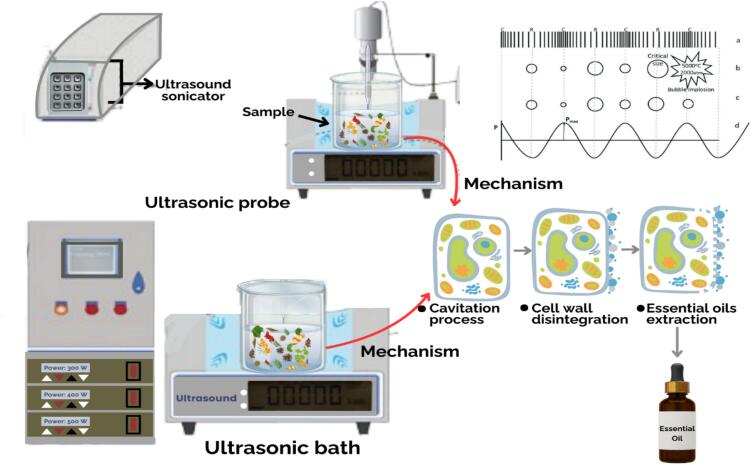

Ultrasounds refer to acoustic waves that range in frequency from 20 to 2000 kHz and in intensity from 10 to 1000 W/cm2. Various applications of ultrasound utilize different combinations of power and frequency. These waves are produced by converting the mechanical vibration of a high-frequency electrical field. [77]. The transducers are the fundamental device generating ultrasonic waves, transforming electrical pulses into the required acoustic energy intensity. Two primary types of transducers used for ultrasound generation are piezoelectric and magnetostrictive. Mainly, there are two types of ultrasound devices commonly used: ultrasonic water bath and sonotrode [34].

3.1. Mechanism

The mechanism of UAE for the extraction of EOs is based on the generation of compression and rarefaction waves, which cause high and low-pressure cycles, ultimately creating small bubbles (cavities) within the liquid or at the surface of the plant material. [43]. The small bubbles generated during the process can be either stable or transient. Transient bubbles are particularly significant in this context due to their involvement in initiating sonochemical reactions. The bubbles undergo contraction and expansion over several consecutive periodic cycles until they become unstable, forming broken daughter bubbles. [60]. Finally, these bubbles collapse and implode, resulting in a phenomenon known as sonoluminescence. This collapse produces high pressure (up to 1000 atm) and temperature (up to 5000 K) within the medium. This entire process called acoustic cavitation, serves as the primary driving force for extracting EOs through ultrasound from plant materials.

Continuous and pulse wave modes are employed to conduct UAE of EOs. Various factors, including frequency, power, time, pulsation, particle size, system type, solvent, temperature, and solvent concentration, are precisely controlled throughout the entire process to achieve optimal extraction of Eos [37], [74], [78]. The extraction of EOs occurs due to the alteration of plant cellular tissues, fragmentation of the plant matrix, breakdown of cells, and variations in the swelling index caused by acoustic cavitation. The dynamic effects of ultrasound-induced cavitation disrupt plant cellular structures, facilitating the release of EOs from the plant material [50], [60]. However, two primary physical phenomena commonly observed in the extraction process of EOs are diffusion in cell membranes and walls and cell wall destruction through the cavitation process. It leads to the rinsing of cell contents, resulting in increased mass transfer and enhancing the overall extraction process [63], [79], [80], as shown in Fig. 4. At times, ultrasound is utilized as a pre-treatment technique for extraction, generating substantial energy waves within the liquid medium of plant materials. This leads to the creation of pores, fluid movement, and micro-turbulence caused by shear forces generated through the resonance of bubbles. Consequently, this method disrupts the lipid glands within cells, leading to an improved extraction of EOs from plants [46], [30], [81]. The augmentation in intensity directly correlates with the enhancement in extraction efficiency. The 20–50 kHz frequency range has been identified as optimal for achieving maximum extraction. As outlined earlier, various processes contribute to extraction, including cavitation, shear stress, poration, fragmentation, and erosion. However, the high extraction yield observed in the UAE cannot be ascribed to a singular mechanism but results from the synergistic combination of multiple mechanisms [82].

Fig. 4.

Ultrasound assisted extraction (ultrasonic probe and ultrasonic bath) of EOs from various plant materials. It is adapted from Boateng et al. (2024) with some modifications.

3.2. Applications

3.2.1. Leaves

Leaves serve as essential plant organs, acting as primary sites for the crucial process of photosynthesis. While leaves' shapes, sizes, and arrangements vary among plant species, they share common functions and structures [26]. The leaf comprises a blade, cuticle, petiole, veins, and stomata, each playing a vital role in maintaining the health and functionality of plants. Rich in chlorophyll, nutrients, minerals, oxygen, carbon dioxide, pigments, hormones, enzymes, and EOs, leaves contain a significant concentration of EOs within specialized structures known as oil glands. These oil glands contribute to various plant functions, such as defense mechanisms, pollination, and resistance to microbes [83]. In numerous studies, EOs have been extracted from leaves through the application of UAE (Table 2).

Table 2.

Ultrasound-assisted with essential oils from leaves.

| Technique applied | Plant | Optimum conditions | Results obtained | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UAP-MAHD | Perilla frutescens L. Britt. leaves | UAP US power = 80, 120, 160, and 200 W, frequency = 45, 80, 100 kHz, time = 0, 5, 10, 20, 40 and 60 min. MAHD Microwave power = 700 W, frequency = 2.45 GHz, liquid–solid ratio = 6, 8, 10, 12 and 14 mL/g, temp = 4 °C. |

The maximum EOs yield (6 mg/g), was achieved through UAP at 160 W power and 80 kHz frequency for 10 min and MAHD at a liquid–solid ratio of 10 mL/g and 700 W power. | [47] |

| UAHD | O. gratissimum, O. basilicum, O. canum, and O. tenuiflorum leaves | US power = 50 W, frequency = 40 KHz 250 mL of double distilled water, time = 30 min. | The extraction yield of EOs obtained was 2.38 % (O. gratissimum), 2.15 % (O. basilicum), 2.41 % (O. canum), and 2.11 % (O. tenuiflorum). | [50] |

| Continuous and Pulsed UAHD | Aloysia citriodora palau leaves | US power = 100 W, frequency = 30 kHz, temp = 25 °C and time = 15, 30 and 45 min, pulsation = 10 s ON– 5 s OFAn | An extraction yield of 2.8 % was achieved in both continuous and pulsed UAE at different time intervals, surpassing the yield obtained from conventional HD, which stood at 2.6 %. | [30] |

| UAP | Tarragon (Artemisia dracunculus L.) leaves | US power = 250, 350, and 500 W, time = 20, 30, and 40 min, 500 mL of distilled water, | The extraction yield varied from 1.87 to 2.18 % at different pretreatment conditions. | [26] |

| Ultrasound-assisted supercritical carbon dioxide extraction | P. frutescens leaves | US power = 185 W, frequency = 40 kHz, P = 10.5–33.0 MPa, temp = 32–55 °C, time = 15 min and CO2 flow rate of 0.13–0.76 g/min. | The extraction yield of 0.71–3.56 % was obtained at different conditions. | [90] |

| UAHD and ultrasound assisted ohmic HD | Lemongrass, basil and coriander leaves | US power = 100 W, frequency = 40 kHz, temp = 80℃, time = 30–90 min | The results indicated that the highest yields for lemongrass, basil, and coriander were 1.63 mL, 0.83 mL, and 0.50 mL at 90 min by UAHD and 2.37 mL, 1.40 mL, and 0.65 mL at 30 min by ultrasound assisted ohmic HD, respectively. | [86] |

| UAP | Betel (Piper betel L.) leaves | US power = 150 W, frequency = 28 and 40 kHz, time = 15, 30 and 45 min | The highest yield of 0.22 % was attained at a frequency of 28 kHz within a 30 min duration. | [83] |

| UAHD | Cytisus trifloruson leaves | US power = 150 W, frequency = 35 kHz, time = 90 min | The extraction yield of 0.053 % was obtained | [91] |

| UAP | Lemongrass leaves | US power = 70, 160 and 250 W, frequency = 40 kHz, temp = 30, 40 and 50 °C, time = 10, 20, and 30 min. | The extraction yield obtained varies from 1.8-3.1 g/100 g in different conditions | [85] |

| UAHD | Java citronella grass leaves | US power = 500 W, time = 21 min, 70 % amplitude, 10:50 pulse interval, and 250 mL distilled water. | A yield of 4.118 % of EOs was obtained at these conditions | [85] |

| UAME | Fresh lavender (L. coronopifolia Poir) leaves | US power = 150 W, Microwave power = 800 W, temp = 70 °C, time = 40 min. | This combinative approach obtained the 1.15 %, EOs yield | [87] |

| UAP combined with drying | Varronia curassavica Jacq. and Ocimum gratissimum Linn. leaves | US power = 1320 W, frequency = 37 kHz, time = 0, 3, 5, 10, 15, 20, and 30 min, temp = 30 °C. | The highest extraction yield of 0.83 % was obtained from V. curassavica leaves when subjected to these conditions at 20 min duration along with 220 min drying time, and 0.81 % was obtained from O. gratissimum leaves at 15 min US time and 285 min drying time. | [84] |

| Ultrasound and HD | Ocimum basilicum leaves | Temp = 100 °C, time = 0, 8, 19, 31 and 38 min. | A yield of 0.08–0.16 was obtained varyintimesme. | [92] |

| UAHD | Perilla leaf (Perillae folium) | US power = 600 W, time = 5 min, and 800 mL deionized water at a liquid: solid ratio of 40:1 (g/g). | The extraction rate of EOs from leaves was 0.67 % | [93] |

| UAE | Sage, bay laurel, and rosemary leaves | The leaf sample was subjected to treatment using a 14 mm diameter ultrasonic probe at 30 % of the maximum ultrasonic power of 10 min. | UAE significantly increased the extraction yield of EOs from 40-65 % from all leaves | [94] |

| UAE | Bitter (V. amygdalina) leaves | US power = 100, 150 and 200 W, frequency = 25 kHz, Temp = 25 °C, time = 10, 20 and 30 min. | The maximum extraction yield of EOs reached 4.185 % g/g under the conditions of 150 W power and a 20 min extraction duration. | [80] |

| Enzyme-UAP |

Artemisia argyi leaves |

US power = 80, 120, 160, and 200 W, frequency = 45, 80, and 100 kHz. | The highest yield achieved was 5.32 mg/g under the conditions of 45 kHz frequency and ultrasonic power of 200 W with a 20-minute extraction duration. | [88] |

| UAHD | P. ferulacea and S. macrosiphonia leaves | US power = 160 W, 600 mL distilled water, frequency = 35 kHz, time = 15 min, temp = 30 °C | The 1.17 and 1.98 v/w, % yield of EOs was obtained from both leaves under these conditions. | [60] |

| Enzyme pretreated UAME | Baeckea frutescens leaves | US power = 478 W, time = 90 min, microwave power = 535 W, and liquid/solid ratio 16 mL/g. | The extraction yield of EOs was 6.38 g/100 g. | [89] |

| Ionic liquids assisted UAE | Seabuckthorn (Hippophae rhamnoides L.) leaves | US power = 200 W, temp = 60 °C, time = 60 min. | The highest extraction yield obtained was 0.095 %. | [95] |

| UAE, MAHD and UAE-MAHD | Lemongrass (Cymbopogon winterianus) leaves | UAE: time = 25 min, ultrasonic bath temp = 30, 40 and 50 °C MAHD: Microwave power = 150, 300, and 450 W frequency = 37 kHz, time = 90 min. |

The extraction yield of EOs was 1.82, 0.92, and 1.48 mg/g by UAE- MAHD, UAE, and MAHD. | [96] |

| UAME | Z. multiflora leaves | US power = 150 W, Microwave power = 800 W, frequency = 20 kHz, t = 12 min, temp = 70 °C. | The highest yield of 0.87 % (w/w) was obtained at these conditions | [97] |

| UAHD | Schinus molle leaves | US power = 50 and 300 W, time = 25 min, temp = 70 °C. | The extraction yield of EOs under UAHD was 2.33 ± 0.21 % at 300 W, while at 50 W, the yield was 1.14 ± 0.11 %. | [98] |

| UAP | P. betle leaves | US power = 750 W, frequency = 24 kHz, temp = 30 °C, time = 20–40 min and leaf-to-solvent ratio (W/V) 1:5. | The extraction yield of oil was 0.16–0.18 g/100 g. | [99] |

| UAOHHD | Citrinella (Cymbopogon citratus) leaves | US power = 108, 144, and 180 W, distilled water 250 mL, temp = 25 °C, Electric current = 3,4 and 5 A | The highest extraction yield of EOs was 22.91 mL/kg aa t US power of 180 W using current of 5 A. | [100] |

UAHD: Ultrasound assisted hydrodistillation, temp: Temperature, US: Ultrasound, EOs: Essential oils, UAE: Ultrasound assisted extraction, UAP: Ultrasound assisted pretreatment, UADAH: Ultrasound-assisted dilute acid hydrolysis, UAVE: Ultrasound-assisted vacuum extraction, MAHD: Microwave assisted hydrodistillation, HD: Hydrodistillation, UAME: Ultrasound assisted microwave extraction, UAM: Ultrasound assisted maceration, UASWE: Ultrasound assisted subcritical water extraction, UMHD: Ultrasound-microwave assisted hydrodistillation, UAOHHD: Ultrasound-assisted ohmic heating hydro distillation

Biru et al. [80] employed UAE with 100–200 W power with 4–8 mL/g liquid–solid ratio for 10–30 min to recover EOs from bitter leaf (Vernonia amygdalina). The highest yield of 4.185 % g/g was achieved at 17 min using a power of 150 W and a liquid–solid ratio 6.8. However, it was observed that as the power increased, the extraction yield of EOs also increased. At very high power levels, an excess of bubbles formed and burst, leading to an increase in the production of free radicals. This elevation in free radicals production increased oil degradation and enhanced solvent evaporation. These findings align with the research conducted by Sneha et al. [50], where authors used UAHD to obtain the EOs from the leaves of various species of the Ocimum plants and assessed their antibacterial, antioxidant, and larvicidal effects. The leaves underwent treatment with 50 W ultrasonic power at a frequency of 40 KHz for 30 min. The yield of UAHD-obtained oil ranged from 2.11 to 2.41 % across different species, exhibiting variations in chemical composition among all oils. Similarly, the antibacterial and larvicidal activities of the EOs varied, attributed to significant differences in their compositions, with the most active ones being O. gratissimum and O. basilicum. Similar results were reported when EOs were extracted from eucalyptus leaves by Al-Khirsan & Al-Yaqoobi [81] by employing UAE in conjunction with HD at 100 °C for 160 min, a yield of 4.1 mL/100 g was obtained. This yield surpassed that achieved by the HD method alone, which yielded 3.85 mL/100 g. This confirms that combining UAE with the conventional technique improved the overall extraction yield. In another study, the combination of ultrasound and HD was applied to obtain EOs from frofro-citronella leaves Solanki et al. [74]. The highest yield of 4 % was obtained at 500 W ultrasound power in 21 min using 250 mL water concentration. The application of ultrasound in conjunction with HD significantly reduced the extraction time. The TPC measured was 13.84 mg GAE/g, and the highest concentration of 27.47 % linalool was identified. This innovative approach demonstrated a 40 % reduction in energy consumption compared to the conventional HD proces, while contributing to a 50 % reduction in carbon footprints.

In numerous studies, ultrasound pretreatment has been applied before conventional extraction methods, such as HD, to enhance the overall extraction processes. Zotti-Sperotto et al. [84] evaluated the impact of UAP and drying on the yield and composition of EOs obtained from Varronia curassavica Jacq. and Ocimum gratissimum Linn. leaves. Ultrasound was applied at a frequency of 37 kHz and 40 °C for 0–30 min. It caused a significant reduction in drying time by 41.0 % (10 min pretreatment) and 24.5 % (5 min pretreatment) and the EOs yield ranged from 0.59 to 0.69 % for and 0.71 to 0.81 % for V. curassavica and O. gratissimum, respectively. The acoustic cavitation and sponge effect induced by ultrasound reduced drying time without causing damage to glandular trichomes. Consequently, the EOs in glandular trichomes remained intact, avoiding volatilization during the drying process. Gupta & Guha [83] also reported a higher yield of EOs from betel leaves (Piper betle L.) obtained by UAP. Pretreatment was conducted using frequencies of 28 kHz and 40 kHz, a power of 150 W, and durations of 15, 30, and 45 min. This resulted in an improvement in the extraction yield of EOs, ranging from 0.18 to 0.22 %. The pretreatment was effective in enhancing extraction by breaking down cell walls and releasing oil from the leaf matrix. The highest concentration of Lemairamin (39.24–42.08 %) was found, indicating a significant impact of UAP on the composition of the extracted oil. Bahmani et al. [26] research showed that using UAP before the HD effectively increased the extraction of EOs from the leaves of tarragon (Artemisia dracunculus L.) UAP was conducted at power levels of 250, 350, and 500 W for 20, 30, and 40 min duration. Subsequently, GC–MS was employed to quantify the oil composition. The obtained yield varied from 1.87 to 2.18 % across various treatments, with the highest achieved at 500 W at the duration of 30 min. Notably, the compound estragole was found in the highest amount in the extracted oil. Balti et al. [85] documented analogous findings in their research on EOs extraction from ultrasound-pretreated dried lemongrass leaves (Cymbopogon flexuosus) by HD. In UAP, a power of 50 W at 50 °C was applied for 25 min before HD, resulting in a substantial increase in the yield of EOs. Under the optimized conditions of extraction, 3.093 g/100 g of oil was obtained from the dried leaves. In another study Kumar et al. [86] conducted pretreatment of leaves of three plants (basil, lemongrass, coriander) for EOs extraction by utilizing ultrasound and OH. Various combinations of these two techniques and their integration with conventional were applied to all the leaves. The outcomes demonstrated that the highest yield of lemongrass (1.63 mL), basil (0.83 mL), and coriander (0.50 mL) was obtained by the application of UAP. However, the combination of ultrasound with OH also proved to be an innovative and sustainable method for oil extraction, offering the advantage of requiring less time and energy.

The limitations of conventional techniques have compelled researchers to explore and implement only novel extraction methods. In an investigation by Chen et al. [47], UAP was applied to Perilla frutescens (L.) britt—leaves, and after that, MAHD was conducted to extract EOs. The ultrasound pretreatment increased the yield of EOs and maintained the integrity of various compounds within the oils. The predominant compound identified was perilla ketone, constituting the most at 80.76 %. Additionally, the EOs exhibited notable antioxidant activity, with an IC50 value of 2.60 μL/mL. Furthermore, the EOs demonstrated superior cytotoxic activity compared to synthetic paclitaxel against human gastric cancer cells. In a similar approach, the UAP was applied before MAHD on Lavandula coronopifolia leaves by Sharifzadeh et al. [87]. The extraction yield increased significantly to 82 %, achieving the highest yield of 1.15 % at a US power of 150 W and a 40 min extraction time. Given that extraction techniques can influence the composition and properties of EOs, this novel approach resulted in oil with maximum antioxidant and antimicrobial potency. Furthermore, the UAE was found to be more eco-friendly compared to MAE. Analogous reports have been documented by Zhang et al. [88] on leaves of Artemisia argyi, EOs extraction pretreating it with aqueous enzyme-ultrasonication. After pretreatment using a combination of enzymes and ultrasound, MAHD was applied to enhance the extraction process further. Enzymes including cellulase, pectinase, and papain were utilized at a concentration of 10 U/mg, in combination with ultrasonic power set at 200 W for 20 min, at a temperature of 50 °C, and at a frequency of 45 kHz. This approach yielded 5.32 mg/g of EOs, exhibiting excellent antioxidant activity and higher inhibitory activity against Phytophthora capsica. In a study by Wan et al. [89], the authors evaluated the impact of UMASE on EO extraction from leaves of Baeckea frutescens. The leaves were pretreated with enzymes to enhance the extraction process. Ultrasonic and microwave power levels of 478 and 535 W were applied for 90 min using a liquid/solid ratio of 16 mL/g. This resulted in the extraction of 6.38 g/100 g of EOs from the leaves, with the highest concentration of the compound α-Pinene (16.13 %) found in the oil. The enzymatic pretreatment before the application of UMASE increased the extraction efficiency by enhancing the destruction of cell walls and membranes in the plants.

3.2.2. Peels

Peels, the outermost layers of fruits and vegetables, are often discarded during processing and cooking. Despite being considered waste, these peels are abundant sources of bioactive compounds, prompting heightened attention towards harnessing the value of this significant byproduct to enhance its environmental sustainability [10], [101]. While peel waste of fruits and vegetables is known to contain substantial amounts of EOs, research efforts have predominantly focused on extracting oils from citrus fruit peels only [4]. A substantial volume of citrus fruits is employed in food processing industries, resulting in significant waste generation as only 40–50 % of the fruit weight is utilized for juice extraction. This considerable amount of peel waste is repurposed for the extraction of EOs, valued for their distinctive properties and versatile applications across various industries [82], [102]. Numerous studies have been undertaken to explore the valorization of this waste for the extraction of EOs (Table 3).

Table 3.

UAE of EOs from waste materials of plants.

| Technique applied | By-product | Optimum conditions | Results obtained | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UAHD | Bitter orange peel | US power = 150 W, frequency = 28 kHz, temp = 20 °C and time = 0–40 min. | The volume-to-mass ratio and extraction time exhibited a significant impact on the volume of extracted EOs. | [42] |

| UAHD | Orange peel | US power = 500 W, frequency = 20 kHz, temp = 96 °C, time = 80 min, and 500 mL distilled water. | The extraction yield increased by 33.3 % in contrast to conventional extraction process | [10] |

| UAHD | Orange peel | US power = 700 W and temp = 25 °C. | The extraction yield obtained from the peel was 2.89 % | [21] |

| UAE | Orange peel | US power = 100 W, time = 5–60 min and temp = 25 °C | The average extraction yield obtained at different time durations by UAE was 0.21 %. | [24] |

| UADAH | Orange peel | US power = 60 W and frequency = 40 kHz. | The extraction yield of EOs was 0.12 % | [31] |

| UAHD | Citrus jambhiri peel | frequency = 33 kHz, time = 45 min, temp = 45 °C and 250 mL of distilled water | The extraction yield of 3.63 ± 0.02 % was obtained from peel powder, and 0.14 ± 0.03 % was obtained from fresh peel. | [4] |

| UAP | Citrus clementina peel | US intensity varied between 1.62 and 49.92 W/cm2, time = 60 min and temp = 14.6–––85.4 °C | The maximum extraction yield of EOs was 134 mg/100 g at 14.6 °C with 25.81 W/cm2 US intensity. | [79] |

| UAP | Tribute citrus peels | Time = 0–120 min, frequency = 455 kHz, and sodium chloride concentration 0–3.0 %, solvent to solid ratio was 10:1–24:1. | The highest extraction yield of 115.072 mg/g of EOs was obtained through the UAP at 40 min time. | [6] |

| UAP | Lime peel | US power = 100 W, frequency = 40 kHz, time = 30, 60, 90 and 120 min and Temp = 30 °C | The EOs extraction yield increased by 7.69, 16.67, 37.66, and 23.38 % for peels subjected to ultrasound treatment for 30, 60, 90, and 120 min, respectively. | [43] |

| UAP | Kumquat peel | US power = 150, 210, 240, and 270 W, and time = 15, 20, 30, and 40 min. | The extraction yield of EOs increased with increasing power and time of UAP. | [103] |

| UAVE | Kumquat peel | US powers = 210, 240, 270, and 300 W, time = 15, 20, 30, 40 min, and Pressures of 600, 700, 800, and 900 mbar, 800 mL of distilled water. | The highest oil yield (1.40 %) was obtained under the conditions of 270 W power for 20 min and a pressure of 800 mbar. | [73] |

| UAHD | Citrus sinensis byproducts | US power = 90–250 W, Pulsation cycle = 9.9 s, time = 30 min, and temp = 38 °C | The extraction time decreased by up to 83 % using UAE with a conventional process. The yield of 8.80 mL was achieved at 10 min of 28.9 Hz sonication. | [51] |

UAHD: Ultrasound assisted hydrodistillation, US: Ultrasound, Temp: Temperature, EOs: Essential oils, UAE: Ultrasound assisted extraction, UADAH: Ultrasound-assisted dilute acid hydrolysis, UAP: Ultrasound assisted pretreatment, UAVE: Ultrasound-assisted vacuum extraction

In research by Heydari et al. [42] on extracting EOs from orange peel waste, the authors applied UAHD for 0–40 min at 20 °C. The researchers noted various concentrations of EOs under varying conditions, with the highest concentration recorded at 0.99 mL/100 g. Within the peel EOs, the maximum TPC reached 108.33 mg GAE/100 mL, comprising 60 % limonene. Karanicola et al. [31] investigated the role of UAE dilute acid hydrolysis of EOs from orange peel. A frequency of 40 kHz and a power of 60 W resulted in the extraction of 0.12 % w/w EOs from the waste. The experimental design proved effective for process analysis and optimization, offering a systematic platform for exploring biomass-based biorefineries. Wan et al. [73] employed UAVE to enhance HD's extraction efficiency from kumquat peel waste. Ultrasound power ranging from 210 to 300 W was applied for 15 to 40 min, leading to a significant increase in the yield of EOs, ranging from 0.96 % to 1.40 %, as compared to samples treated with HD alone. This approach not only boosted the yield but also preserved the antioxidant activity of the extracted EOs.

Ultrasound is sometimes applied as a pretreatment, where plant materials undergo treatment with ultrasonic waves before the subsequent extraction process. The primary objective is to prepare the material for more effective extraction during the subsequent steps [10], [45]. In a study by Teke et al. [79] the authors explored the effectiveness of UAP in obtaining EOs from citrus peel. Under extraction conditions with a temperature of 14.6 °C and ultrasound intensity of 25.81 W/cm2, a yield of approximately 134 mg/100 g of EOs was obtained. The study also demonstrated the impact of oil extraction on bioethanol production from citrus waste. The results revealed the effectiveness of the pretreatment method in enhancing bioethanol production from waste. The maximum recovery of oil was found to enhance the bioethanol production process. In a similar study, UAP on citrus peel waste was documented by Sandhu et al. [10] for the extraction of EOs in a short time. The highest yield of 33 % was attained at an ultrasound power of 500 W. This achievement can be attributed to the increased mass transfer facilitated by the disruption of plant cell walls, enabling the solvent to penetrate the sample material, resulting in enhanced extraction.

Scientists have employed UAE with conventional and novel techniques in various research endeavors. This approach aims to enhance extraction efficiencies or evaluate and compare the effectiveness of different methods in the extraction of EOs. Xhaxhiu and Wenclawiak [24] extracted the EOs from orange peel by applying UAE and SFE-CO2. UAE applied for 5–6 min at a power of 10 W yielded 0.21 %, whereas SFE-CO2 at 200 atm yielded a slightly higher yield of 0.23 % EOs. GC–MS analysis confirmed the oil composition, indicating a concentration of 89–91 % limonene in the extracted EOs from the peel. The elevated temperature and pressure conditions associated with SFE-CO2 may account for the observed higher yield compared to UAE. In an investigation by Priyadarshi et al. [4], EOs from fresh peel and peel powder of C. jambhiri were extracted using HD and UAHD. UAHD at 45 °C for 45 min with a fixed frequency of 33 kHz significantly outperformed HD at 4 °C for 180 min in terms of EOs yield. Powdered peels treated with UAHD achieved the highest EOs yield at 3.63 %, while fresh peels treated with HD yielded the lowest at 0.14 %. This difference likely stems from the increased surface area of dried peel. As the particles become smaller, they provide more contact points with the solvent, facilitating improved EOs extraction. Interestingly, extraction time also significantly impacts EOs yield across all conditions. Analogous reports have been documented by G. Li et al. [6] on the extraction of EOs from Tribute citrus peels. The authors compared the HD and UAP methods and applied the Box-Bhenken design to optimize both processes. UAP emerged victorious, yielding a significantly higher EOs content 114.02 mg/than HD (85.67 mg/g), even at a shorter extraction time of 40 min. Both methods revealed the presence of 30 distinct compounds, with limonene as the most abundant component, clocking in at around 86 % in both HD and UAP extracts. Arafat et al. [43] stated that the UAP process boosted the EOs recovery from sweet lime peel waste. Following pretreatment by ultrasound, the MT was employed at a power range of 500–1000 W for an extraction time of 25 min to achieve the maximum amount of EOs from the peel. A yield of 0.792 % was obtained, and GC–MS analysis revealed the presence of 50 compounds, with limonene constituting the highest content at 43 % in the EOs. Moreover, UAP led to an increase in the oil yield from 0.84 % to 1.06 % as the treatment time extended from 30 to 90 min. Another similar study was conducted by Yu et al. [103] in which authors determined the effects of UAP and MT on various parameters of EOs obtained from the citrus kumquat peel. Under UAP and MT at 210 W and 300 W, respectively, with extraction times of 30 and 6 min, the oil yield showed a significant increase compared to the yield obtained by HD alone. Moreover, in comparison with MT, UAP resulted in a higher oil yield, and the extracted oil exhibited superior antioxidant activity.

3.2.3. Seeds

Seeds, the mature fertilized ovules of flowering plants, serve as reproductive structures with food reserves. Their formation occurs when the anther and stigma unite during pollination. Certain seeds are valuable sources of EOs, prompting research on applying ultrasound technology for EO extraction from seeds (Table 4). Smigielski et al. [52] reported that UAM enhanced the extraction yield of EOs from waste carrot seeds (which had lost germination ability). The quality and bioactivity of the extracted oils were preserved in the process. Specifically, a sonication time of 20 min, impulse time of 50 s, and sonication temperature of 20 °C resulted in a 33 % increase in oil yield (from 0.82 to 0.92 g/100 g of seeds). The oil obtained had the highest concentration of around 35 % carotol, and the ultrasound-treated oil exhibited a lighter scent. A study by Zorga et al. [45] demonstrated that UAHD is an efficient process for obtaining high-quality EOs with substantial biological activity from celery seeds. Sonication was applied at amplitudes ranging from 20 % to 100 % for 5 to 50-minute durations using various water concentrations, followed by an HD process. The optimized process yielded 2.15 g/100 g of EOs from seeds with an efficiency of 48 %. The cavitation phenomenon induced increased solvent circulation, enhanced swelling of plant material, and ultimately improved mass transfer. GC–MS analysis revealed the highest constituent, with limonene comprising 76.9 % of the oil. The recovery of EOs from the seeds of cardamom by the UAE coupled with ICPDT has been documented by Castillo et al. [53]. Thirteen different conditions were applied, leading to various extraction yields. The highest yield was obtained with the application of the 6th treatment, resulting in 22 % (w/w) with a concentration of 1.1263 g of EOs. The coupling of these two technologies significantly enhanced the yield through cell disruption and solvent diffusion. Oubeka et al. [104] assessed the influence of UAP, followed by HD and MAHD, on the extraction of EOs from caraway seeds. Ultrasound was applied using an ultrasonic bath at a frequency of 40 kHz for 30 min at 25 °C, resulting in oil yields ranging from 1.18 to 1.36 % w/w. The extracted oil exhibited a fresh scent and had a pale yellow color. GC–MS analysis confirmed the presence of 21 compounds, with limonene being the most abundant. Analogous reports have been documented by Liu et al. [105]on the extraction of EOs from Iberis amara seeds by UAHD. Utilizing 75 W ultrasound power with a solvent-to-sample ratio of 6.7 mL/g for 240 min led to a yield of 0.42 % (v/w) of EOs. GC–MS analysis confirmed the presence of 28 compounds, with the highest composition being 4-Carvomenthenol (18.75–22.13 %).In another study, by utilizing UAE, EOs from the wastewater of dill seeds were recovered by Najafipour et al.[25]. A 6 g powder sample was introduced to a 90 mL methanol-ethanol solvent and subjected to treatment with 400 ultrasound power at a frequency of 24 kHz at 40 °C for 75 min. The results demonstrated a 38 % yield of EOs from the wastewater of dill seeds, with dihydrocarvone constituting 35.929 % of the obtained oil.

Table 4.

UAE of EOs from various plant materials.

| Technique applied | Plant materials | Optimum conditions | Outcomes | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UAM | Carrot seeds | time = 5–50 min, 10–99 s pulse time, temp = 20-60℃ | The maximum extraction yield of 0.95 g/100 g from seeds was attained following a 20 min duration, with an impulse time of 99 s, and at a temperature of 45℃. | [52] |

| UAHD | Celery Seeds (Apium graveolens L.) | Time = 50, 70, and 90 min, pulse range 0.1, 0.5, and 1.0, and water = 350, 700, and 950 mL | The extraction yield of 2.15 g/100 g of EOs was obtained from seeds at 50 min sonication | [45] |

| UAE | Dill (Anethum et al.) seeds | 90 mL of 50 v/v % methanol-ethanol solvent, US power = 400 W, frequency = 24 kHz, temp = 40℃ and time = 75 min | The recovery of EOs achieved was 38.65 % under these conditions | [25] |

| UAE and ICPDT | Cardamom seeds | Pressure = 0.17–0.7 Mpa, Ethanol: water (90:10 v/v), pulse/pause mode = 19 min, temp = 45 °C, and amplitude 50 % | The highest oil extraction yield was 22 %, obtained by coupling both techniques. | [53] |

| UAP-HD | Caraway seeds | Frequency = 40 kHz, time = 30 min, and temp = 25 °C | The highest extraction yield of oil obtained was 1.36 % w/w. | [104] |

| UAHD | Iberis amara seeds | US power = 250 W, frequency = 25 kHz, time = 240 min and distilled water 250 mL | The extraction yield of EOs obtained at these conditions was 0.42 ± 0.05 %. | [105] |

| UAILMHD | Paeonia suffruticosa Andr. ‘Jitsugetsu Nishiki’ flowers | US power = 400 W, time = 20 min, and 1800 mL solvent of 5, 10, 15, and 20 % concentration, | The extraction yield of 1.53 g/100 g was obtained at these conditions. | [46] |

| UAME | Sweet cherry flowers | US power = 50 W, frequency = 25 kHz and Methanol: chloroform: ddH2O 5:2:2, v/v/v | The extraction yield varies with the from 0.25-1.25 %. | [56] |

| UAP and UAHD | Oliveria decumbens flowers | US power = 50, 100, 150, 200, and 250 W, temp = 40 °C and time = 20 min | The extraction yield ranged between 3.30 and 5.80 % for various treatments. | [54] |

| UAE | (S. grandiflora), (S. rubriflora), (S. sphenanthera), and (S. propinqua) fruits | US power = 180–300 W, time = 10–50 min and temp = 30-50℃ | The highest extraction yield of all fruits was obtained at 30 min, 30 °C, and 240 W power (5.88, 6.11, 6.91 and 7.51 %). | [106] |

| Ultrasound/ Microwave-assisted deep eutectic solvent |

Schisandra chinensis fruit | US power = 550 W and Solvent = 300 mL | The extraction yield of EOs was 12.2 mL/kg. | [55] |

| UAE, MAE, and UMAE | White and black pepper fruit | US power = 50 W, frequency = 40 kHz, Microwave power = 80 W, temp = 100 °C, and 100 mL distilled water | The yield of EOs from white pepper fruits obtained by UMAE was 4.1 %, marking a 20 % increase compared to UAE at 3.4 % and a 10 % increase compared to MAE at 3.7 %. This trend was similarly observed in the case of black pepper fruits. | [57] |

| UAP | Pistacia lentiscus berries | US power = 20, 40, 60 W, frequency = 25 kHz, temp = 25 °C, time = 15 min and plant material to water 1: 4, 8 and 12. | The highest yield of EOs from berries was 0.66 ± 0.03 % obtained at 60 min duration, using US power of 60 W and solid–liquid ratio of 1 g: 12 mL. | [20] |

| UAHD | Cinnamomum cassia bark | US power = 250, 300 and 350 W, extraction time = 45, 60, and 75 min, and liquid–solid ratio = 5, 6, 7 mlL.g−1 | The average extraction yield of EOs was 2.14 % obtained at different conditions. | [2] |

| UAE | Nutmeg and mace (Myristica fragrans Houtt.) | US power = 150, 250, 300 and 400 W, time = 15, 20, 30 and 40 min, frequency = 25 kHz, and temp = 25 °C | The highest extraction yield was obtained for mace (0.145 g oil/g) and nutmeg (0.063 g oil/g) at 30 min with US power of 250 W | [107] |

| UASWE | Cinnamon barks | US power = 0–250 W, frequency = 15–38 kHz, time = 25 min, temp = 140 °C, and Pressure = 5 MPa | The yield of EOs reached 12.662 mg/g under the following conditions: 140 °C temperature, 25 min of extraction time, 5 MPa pressure, a liquid-to-solid ratio of 8 mL/g, US power set at 145 W, and a frequency of 18.5 KHz. | [108] |

| UAE | Clove buds | US power = 100–500 W, time = 20 min, and 150 mL n-hexane. | UAE resulted in an average extraction yield of 71 % at different conditions. | [109] |

| UAE | Clove buds | US power = 158 W, temp = 38 °C, and time = 30 min. | The extraction yield of oil was 20.04 %. | [110] |

| UAHD | Clove buds | US power = 400 W, time = 20–60 min, and 40 % amplitude. | The extraction yield of oil obtained was 15.23 %, w/w at 50 min using 400 W power. | [58] |

| UMHD | M. officinalis aerial parts | Bath ultrasonicator was used at frequency = 45 kHz and US power = 180, 300, 420 and 540 W Microwave power = 280, 420, 560 and 700 W, temp = 25 °C and time = 30, 45, 60 and 90 min |

The oil extraction yield was 0.18 ± 0.0019 % and obtained at US and microwave power of 420 W at 60 min duration. | [111] |

UAM: Ultrasound assisted maceration, temp: Temperature, EOs: Essential oils, UAHD: Ultrasound assisted hydrodistillation, US: Ultrasound, UAE: Ultrasound assisted extraction, ICPDT: Instant controlled pressure drop technology, UAP: Ultrasound assisted pretreatment, HD: Hydrodistillation, UAILMHD: Ultrasound assisted ionic liquid mediated hydro-distillation, UAME: Ultrasound assisted microwave extraction, MAE: Microwave assisted extraction, UASWE: Ultrasound assisted subcritical water extraction, UMHD: Ultrasound-microwave assisted hydrodistillation.

3.2.4. Flowers

Flowers, the reproductive organs of a diverse group of land plants called angiosperms, are commonly referred to as flowering plants. These plants produce seeds from the ovary, which is located within the flowers. The distinct aroma of flowers is attributed to their aromatic compounds. Additionally, many flowers contain EOs, which were extracted in some research studies using UAE (Table 4). In research by Lei et al. [46] on extracting EOs from the flowers Paeonia suffruticosa Andr. ‘Jitsugetsu Nishiki, the authors employed UILHD. The ionic liquid, specifically 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium bromide (10 %), was employed under optimal 400 W ultrasound power conditions for 20 min. This process resulted in a yield of 1.53 g/100 g, with the highest concentration of trimethoxybenzene (16 %) in the extracted oil. The increase in yield was significant with the increase in power from 200 to 400; however, at 500 W, there was no further increase in the yield of EOs. Zhang et al. [56] compared UAE and MAE to extract EOs from sweet cherry flowers. A 50 W ultrasound power at a frequency of 25 kHz was applied, resulting in a concentration yield increase ranging from 0.25 % to 1.25 %. GC–MS analysis revealed the presence of 155 volatile compounds in the oil, with the highest concentration observed of some aldehydes, alcohols, ketones, and esters. Mollaei et al. [54] pretreated Oliveria decumbens Vent flowers with ultrasound and conducted the UAHD to obtain the EOs afterward. The highest yield of EOs, amounting to 5.82 %, was obtained at an ultrasound power of 149 W and a temperature of 38.63 °C for 25 min. The increase in power correlated with an increase in yield, but only up to a certain point, beyond which the yield started to decrease. GC–MS analysis revealed that thymol and carvacrol constituted the most abundant components in the oil, accounting for 60 % of the composition. Furthermore, the oil obtained by UAHD exhibited higher antioxidant activity, with an IC50 value of 29.61 μg/mL.

3.2.5. Fruits

In botanical terms, fruits are the mature ovary of flowering plants, typically containing seeds. It develops from the fertilized ovule after pollination. Fruits play a crucial role in seed dispersal and are often consumed by humans due to their sweetness and nutritional value. Table 4 presents the studies conducted on the extraction of EOs from fruits of various plants. In X. Wang et al. [106] research, UAE was utilized for obtaining EOs from the fruits of four different plants. Various conditions, including ultrasonic power (180–300 W), extraction time (10–50 min), and temperature (30-50℃), were applied to explore their impact on EO extraction. The yields varied across different conditions, with the highest yields obtained from S. grandiflora (7.51 %), S. rubriflora (6.91 %), S. sphenanthera (6.11 %), and S. propinqua (5.88 %). The analysis of the extracted oils revealed the presence of 86 compounds, with some compounds common to the fruits of all four plants. Li et al. [55] researched a combined ultrasound/microwave-assisted UAHD approach with DES to extract EOs from Schisandra chinensis fruits. The 10 g sample underwent treatment with 550 W ultrasound and 250 W microwave power using 300 mL DES. This methodology resulted in a yield of 8.56 g/100 g of EOs from the fruits. The EOs exhibited an IC50 value of 52.34 µg/mL for scavenging DPPH. Y. Wang et al. [57] did a comparative analysis of EOs extraction from white and black pepper fruits using UAE, MAE, and UMAE involved conditions of ultrasound and microwave power at 50 and 800 W, a frequency of 40 kHz, 100 mL distilled water, and a temperature of 100 °C. UMAE exhibited a higher yield than MAE and UAE due to the facilitation of cell breakage and oil leakage. The obtained EOs from white and black pepper fruits through UMAE were both 4.1 %, comprising 29–30 compounds. The intensified mass transfer, enhanced penetration, and cell disruption induced by ultrasound and microwave contributed to the increased oil yield from the fruits. Moreover, the radical scavenging activity of the oil obtained through UMAE surpassed that of other techniques. Belhachat et al. [20] stated that under optimal conditions of ultrasound pretreatment with 20, 40, and 60 W at a frequency of 25 kHz and a temperature of 25 °C for 15 min, the yield of EOs from ripe berries of P. lentiscus was 0.66 g/100 g. The yield increased with prolonged extraction time and increased ultrasonic power but reached a limit beyond which it started to decrease. Sonication facilitated the release of oil from the destroyed oil glands in the berries. The obtained oil exhibited moderate antioxidant properties.

3.2.6. Others

EOs extraction studies have been conducted on various plant parts, including bark and buds (Table 4). Kaur et al., [107] studied EOs extraction from nutmeg and mace in the UAE and compared it with other conventional and novel techniques. UAE was employed on powders using ultrasound powers of 150, 250, 300, and 400 W, extraction times of 15, 20, 30, and 40 min, a frequency of 25 kHz, and a temperature of 25 °C. The results revealed that the EOs yield from mace was 0.145 g oil/100 g, and from nutmeg, it was 0.063 g oil/100 g. The increase in power led to an increase in yield, but only up to a certain limit, as excessive cavitation caused bubbles to collide in a non-spherical manner, diminishing the implosion impact. In research by Guo et al. [108] on USWE of EOs from cinnamon, the researchers reported that it had higher efficiency than other techniques. Using an ultrasound power of 145 W, an extraction time of 25 min, a temperature of 140 °C, a pressure of 5 MPa, and a frequency of 18.5 kHz, the yield of EOs obtained from cinnamon bark was maximized. The highest yield achieved was 12.662 mg/g. This method resulted in high-quality oil and significantly reduced the extraction time compared to other commonly used techniques. Similar trends of high recovery of yield have been documented by G. Chen et al. [2]. The study reported that treating Cinnamomum cassia bark with UAHD yielded 2.14 % extraction of EOs. Experiments were conducted at 250, 300, and 350 W ultrasound powers for 25, 30, and 35 min durations, with a liquid-to-solid ratio of 5, 6, and 7 mL/g. UAHD demonstrated a quicker extraction process with a 27 % higher yield than HD. The energy consumption for UAHD was 790 W, significantly lower than the 1490 W used in HD.

Furthermore, the composition of the EOs obtained through each process exhibited notable differences. The analysis revealed that the ultrasound-induced cracks and gaps on the bark contributed to an enhanced yield. Yunusa et al. [109] compared the UAE with conventional soxhlet extraction in the extraction of EOs from clove buds. A 20 g dried sample was subjected to UAE using 100–500 W ultrasound power for 20 min with 150 mL of n-hexane. The yield of EOs obtained by UAE was 71 %, while conventional soxhlet extraction yielded 54 %. Notably, the UAE process required only 20 min compared to the 6 h needed for the conventional method.

Additionally, there were distinct differences in the composition and density of the oils extracted from both techniques, highlighting the efficiency of UAE in EOs extraction. In a study by Jadhav et al. [58], the yield of EOs obtained by UAHD from clove buds was 15.23 %, w/w, and in another study by Ghule & Desai [110] using UAE, the yield of oil obtained from clove buds was 20.04 %. The authors observed that the yield obtained from these processes was higher than that obtained from conventional methods. This difference in yield is attributed to the cavitation phenomenon, which causes more damage to plant materials' cell walls than conventional techniques. Ye et al. [87] research showed that using coupled ultrasound and microwave with HD enhanced the extraction of EOs from aerial parts of Mellissa officinalis. Under optimized conditions (frequency: 45 kHz, temperature: 25 °C, duration: 30 min) using an ultrasonic bath, the highest oil yield obtained was 0.21 ± 0.0019 %. This yield was 75 % higher compared to conventional processes. The study highlighted the importance of extraction equipment as a significant factor affecting oil yield, as it varied for the same plant when different equipment was used.

3.3. Potential trends and constraints in UAE implementation

The growing utilization of ultrasound technology for extracting EOs from different plant materials has revealed promising trends. These include combining UAE with various chemicals and thermal and non-thermal techniques, which have prove more effective than solely on ultrasound. Particularly noteworthy are the outcomes of studies that have explored ultrasound coupling with other non-thermal techniques for EOs extraction, as they have demonstrated the best results [2], [21], [45]. The increasing application of ultrasound techniques, including continuous and pulsed ultrasound, high-frequency ultrasound, or dual-frequency ultrasound, in EOs extraction has demonstrated promising outcomes. These techniques effectively achieve high yields by efficiently disrupting the cell structure of tough materials [30] The rising adoption of environmentally friendly solvents, such as supercritical fluids or natural DES, in UAE has led to enhanced extraction yields compared to commonly used toxic organic solvents [46], [93]. However, considerations and limitations are associated with using UAE to extract EOs from plant materials. High intensities in the UAE can lead to heat generation, causing potential physical and chemical damage to the sample. The choice of frequency and power is critical, and optimization is necessary for effective ultrasound treatment. Low-frequency high-power ultrasound is commonly employed to create fewer, larger bubbles, generating more energy. Finding the right balance and optimizing energy parameters before applying ultrasound treatment to the sample for optimum extraction [112]. Another drawback of ultrasound treatment is the generation of free radicals during cavitation, which can have both positive and negative effects. While free radicals can contribute to the extraction process, excessive production may decrease efficiency. Balancing the power level is crucial to achieving the desired outcomes without compromising the overall effectiveness of the UAE [26]. Thus, the number of cavitation bubbles increases with power increases, leading to a large inter-bubble collision, degeneration, and breakdown of non-spherical structure, which may decrease the impact of the bubble implosion. Further, the superheated confined temperatures and maximum free radical generation during the bubbles' implosion may also cause bioactive compounds' deformation and thus minimize the extraction yield [2]. Ultrasonic time of 10–30 min delivered the maximum yield of EOs. However, too extensive or too little ultrasonic time resulted in an undesirable impact on the yield of EOs extracted from cassia bark [2], [88]. Another problem is the design of the cell and the loss of ultrasonic power during the process. The cell must be constructed to withstand the pressure generated by the waves. Additionally, the expense of ultrasound equipment poses a considerable hurdle, as does the need for affordable raw materials. The high energy demand for generating intense ultrasound waves further increases costs. Although ultrasound proves highly effective on a laboratory scale, the transition to industrial applications presents significant scaling-up challenges. Addressing these issues requires careful consideration of cell design, power loss, equipment costs, and the overall feasibility of large-scale implementation [113]. Furthermore, integrating artificial intelligence is crucial to enhance the efficiency of UAE further to meet the growing demand for EOs. This technological advancement streamlines the entire process and should be applied in novel non-thermal techniques to achieve better results.

4. Conclusion and future perspectives

To optimize the value addition and mitigate environmental pollution risks, it is crucial to sustainably recover EOs from plant materials for applications in food, pharmaceutical, cosmetic, and other industries. UAE emerges as an eco-friendly and cost-effective method for extracting EOs from various plant sources. The literature review underscores the progress of the UAE in enhancing extraction efficiency for these valuable substances, considering their trace amounts in plant materials. UAE demonstrates improved efficiency, high selectivity, durability, scalability, and cost-effectiveness. Its combination with other conventional and novel techniques has further boosted extraction efficiency. Despite these advancements, a key challenge is the limited application of UAE, primarily at the laboratory scale. Collaborative efforts among government bodies, research facilities, and industry stakeholders are essential to scale up the UAE for industrial extraction processes to leverage its potential. Exploring a broader range of plant materials, especially those yet to be explored on a large scale is vital for comprehensive EOs extraction. Safety studies should accompany these efforts to assess potential toxic effects, guiding the application of extracted oils in various products. Additionally, investigating the combined effects of innovative extraction techniques through collaborative research is recommended for maximizing efficiency. Future studies should focus on pilot-scale applications and diversify the range of plant materials used in EOs extraction.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Samran Khalid: Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Kashmala Chaudhary: Illustration preparation, Writing – review & editing. Sara Amin: Draft writing, Table preparation, Writing – review & editing. Sumbal Raana: Writing – review & editing. Muqaddas Zahid: Writing – review & editing. Muhammad Naeem: Writing – review & editing, Supervision. Amin Mousavi Khaneghah: Writing – review & editing, Funding, Supervision. Rana Muhammad Aadil: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Supervision.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Contributor Information

Samran Khalid, Email: samrankhalid08@gmail.com.

Kashmala Chaudhary, Email: kashmalach913@gmail.com.

Sara Amin, Email: saraamin601@gmail.com.

Sumbal Raana, Email: sraana56@gmail.com.

Muqaddas Zahid, Email: muqaddasfst63@gmail.com.

Muhammad Naeem, Email: m.naeem@uaf.edu.pk.

Amin Mousavi Khaneghah, Email: mousavi@itmo.ru, mousavi.amin@gmail.com.

Rana Muhammad Aadil, Email: muhammad.aadil@uaf.edu.pk.

Data availability

No data was used for the research described in the article.

References

- 1.Alshaikh S.M., Al-Zaidi A.A., Al-Badr° N.A., Herab A.H. Households' attitudes towards food safety guidance in riyadh. Saudi Arabia. Int J Agri Biosci. 2023;12(4):262–266. doi: 10.47278/journal.ijab/2023.075. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen G., Sun F., Wang S., Wang W., Dong J., Gao F. Enhanced extraction of essential oil from Cinnamomum cassia bark by ultrasound assisted hydrodistillation. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2021;36:38–46. doi: 10.1016/j.cjche.2020.08.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khalid S., Naeem M., Talha M., Hassan S.A., Ali A., Maan A.A., Bhat Z.F., Aadil R.M. Development of biodegradable coatings by the incorporation of essential oils derived from food waste: A new sustainable packaging approach. Packag. Technol. Sci. 2024;37(3):167–185. doi: 10.1002/pts.2787. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Priyadarshi S., Kashyap P., Gadhave R.K., Jindal N. Effect of ultrasound-assisted hydrodistillation on extraction kinetics, chemical composition, and antimicrobial activity of Citrus jambhiri peel essential oil. J. Food Process Eng. 2021;44(12):e13904. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Al-Hoshani N., Al Syaad K.M., Saeed Z., Kanchev K., Khan J.A., Raza M.A., Atif F.A. Anticoccidial activity of star anise (illicium verum) essential oil in broiler chicks. Pak Vet J,43(3) 2023 doi: 10.29261/pakvetj/2023.050. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li G., Liu S., Zhou Q., Han J., Qian C., Li Y., Meng X., Gao X., Zhou T., Li P. Effect of response surface methodology-optimized ultrasound-assisted pretreatment extraction on the composition of essential oil released from tribute citrus peels. Front. Nutr. 2022;9 doi: 10.3389/fnut.2022.840780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moseri H., Umeri C., Onyemekonwu R., Belonwu E. Assessment of cassava peel/palm kernel cake meal (PKM) on growth performance and blood parameters of lactating sows (agricultural extension implication) Int J Agric Biosci. 2023;12:66–70. doi: 10.47278/journal.ijab/2023.045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dalal D., Kunte S., Oblureddy V., Anjali A. Comparative evaluation of antimicrobial efficacy of German chamomile extract, tea tree oil, and chlorhexidine as root canal irrigants against e-faecalis and streptococcus mutans-An In Vitro study. Int J Agric Biosci. 2023;12(4):252–256. doi: 10.47278/journal.ijab/2023.072. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Radwan IA-H, Moustafa MM, Abdel-Wahab SH, Ali A, Abed AH. Effect of essential oils on biological criteria of gram-negative bacterial pathogens isolated from diseased broiler chickens. Int J Vet Sci,11(1) (2022),59-67. https://doi.org/10.47278/journal.ijvs/2021.078.

- 10.Sandhu H.K., Sinha P., Emanuel N., Kumar N., Sami R., Khojah E., Al-Mushhin A.A. Effect of ultrasound-assisted pretreatment on extraction efficiency of essential oil and bioactive compounds from citrus waste by-products. Separations. 2021;8(12):244. doi: 10.3390/separations8120244. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brenda V.D., Zain M., Agustin F. Strategy to reduce methane to increase feed efficiency in ruminants through adding essential oils as feed additives. Int J Vet Sci. 2024;13(2):195–201. doi: 10.47278/journal.ijvs/2023.087. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moosavi-Nasab M., Behroozi B., Gahruie H.H., Tavakoli S. Single-to-combined effects of gelatin and aloe vera incorporated with Shirazi thyme essential oil nanoemulsion on shelf-life quality of button mushroom. Qual Assur Saf Crops Foods. 2023;15(2):175–187. doi: 10.15586/qas.v15i2.1241. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang L., Yu M., Ding S., Cao J., Meng X., Li L., Sa R., He M., Sun M. Zebrafish models for the evaluation of essential oils (EOs): A comprehensive review. Qual Assur Saf Crops Foods. 2023;15(4):156–178. doi: 10.15586/qas.v15i4.1384. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bouayad D., Grar H., Berzou S., Kheroua O., Saidi D., Kaddouri H. Marjoram oil attenuates oxidative stress and improves colonic epithelial barrier function in dextran sulfate sodium-induced ulcerative colitis in Balb/c mice. Ital. J. Food Sci. 2023;35(1):106–117. doi: 10.15586/ijfs.v35i1.2320. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rout S., Tambe S., Deshmukh R.K., Mali S., Cruz J., Srivastav P.P., Amin P.D., Gaikwad K.K., de Aguiar Andrade E.H., de Oliveira M.S. Recent trends in the application of essential oils: The next generation of food preservation and food packaging. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2022;129:421–439. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2022.10.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yadav A., Kumar N., Upadhyay A., Singh A., Anurag R.K., Pandiselvam R. Effect of mango kernel seed starch-based active edible coating functionalized with lemongrass essential oil on the shelf-life of guava fruit. Qual Assur Saf Crops Foods. 2022;14(3):103–115. doi: 10.15586/qas.v14i3.1094. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Souza Pedrosa G.T., Pimentel T.C., Gavahian M., de Medeiros L.L., Pagán R., Magnani M. The combined effect of essential oils and emerging technologies on food safety and quality. Lwt. 2021;147 doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2021.111593. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pandey J., Acharya S., Bagale R., Gupta A., Chaudhary P., Rokaya B., Manju K., Aryal P., Devkota H.P. Physicochemical evaluation of Prinsepia utilis seed oil (PUSO) and its utilization as a base in pharmaceutical soap formulation. Qual Assur Saf Crops Foods. 2023;15(2):188–199. doi: 10.15586/qas.v15i2.1176. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ara C., Arshad A., Faheem M., Khan M., Shakir H.A. Protective potential of aqueous extract of allium cepa against tartrazine induced reproductive toxicity. Pak Vet J,42(3) 2022 doi: 10.29261/pakvetj/2022.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Belhachat D., Mekimene L., Belhachat M., Ferradji A., Aid F. Application of response surface methodology to optimize the extraction of essential oil from ripe berries of Pistacia lentiscus using ultrasonic pretreatment. J. Appl. Res. Med. Aromat. Plants. 2018;9:132–140. doi: 10.1016/j.jarmap.2018.04.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]