Loss of desire for sexual activity is the commonest presenting female sexual dysfunction and often the hardest to treat. Whether this loss of sexual desire should be seen as abnormal or simply as a variation of normal has long been debated. Much literature is available on female loss of desire, considering sexuality for women from various angles. The American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV), which gives our working classification of psychosexual dysfunction, would classify it as hypoactive sexual desire disorder and sexual aversion disorder.

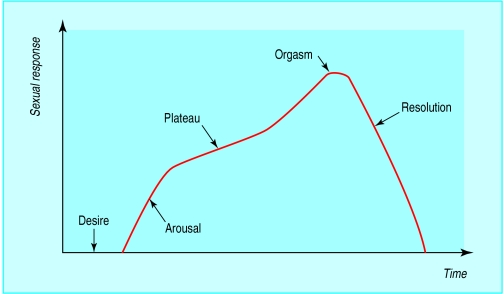

Masters and Johnson’s original “human sexual response curve” helps us to understand loss of desire in the context of the normal sexual response. This diagrammatic representation describes increasing sexual pleasure against time—desire for sexual activity followed by arousal, orgasm, and finally resolution. It is important to remember, however, that the physiologies of desire, arousal, and orgasm are separate entities and therefore are not dependent on each other. Women with loss of desire (hypoactive sexual desire disorder) can have good sexual functioning. In essence, they will not initiate sexual contact.

Is desire a thought or a feeling? The answer is not clear, and, certainly early in loving relationships, physical arousal closely follows any sexual thought. Initially, we have a sexual thought, which then facilitates the arousal mechanism through neurological pathways. The thought could be anticipation of the evening ahead or a memory of a previous sexual encounter. Women who do not desire sexual activity can operate quite well sexually once engaged in the sexual encounter. Touch around the clitoris and genital area facilitates neurological pathways, producing good arousal, good lubrication, and on to orgasm.

Causes of loss of desire

Much research into sexual desire is being undertaken, but it is still poorly understood. We know that certain medical conditions affect it. For example depressive illness often dramatically reduces it, as do stress and fatigue.

Organic causes

Testosterone has a part to play in women’s sexual desire, although much smaller amounts are required than in men. In women testosterone production is split evenly between the ovaries and the adrenal gland. Androgen deficiency syndrome should be considered after both hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, and chemotherapy for cancer, when treatment with testosterone can improve loss of desire. Conditions and drugs that cause hyperprolactinaemia have a direct effect on reducing sexual drive.

Possible causes of hyperprolactinaemia

| • Pituitary tumours | • Hypothalamic diseases |

| • Hypothyroidism | • Hepatic disease |

| • Cirrhosis | • Breast surgery |

| • Stress | • Drug treatments |

Drugs that can affect women’s sexual function

| • Antiandrogens | • Cytotoxic drugs |

| Cyproterone | • Psychoactive drugs |

| Gonadotrophin releasing hormone | Sedatives |

| analogues | Narcotics |

| • Antioestrogens and other hormones | Antidepressants |

| Tamoxifen | Neuroleptics |

| Contraceptive drugs | Stimulants |

The effect of changing hormone patterns at different life stages is poorly understood, but it is well known that loss of desire is more common with premenstrual tension, postnatally, and around the menopause. Many drugs can also cause loss of desire, and it can be secondary to poor sexual arousal and lack of orgasm.

Any health problem that might affect sexual anatomy, the vascular system, the neurological system, and the endocrine system must be considered. Indirect causes are conditions that can cause dyspareunia; that cause chronic pain, fatigue, and malaise; and that interfere with the vascular and neurological pathways.

Illnesses that may result in loss of sexual desire

Gynaecological disorders causing pain on sexual intercourse

Obstetric disorders causing pain on sexual intercourse

Urological disorders causing pain on sexual intercourse

Alcohol and substance misuse

Stress and chronic anxiety

Endocrine disorders

Neurological disorders

Psychiatric disorders

Depression

Fatigue

Psychological causes

It is often difficult to disentangle organic possibilities from psychogenic variables that occur in women at different life stages and the effect that these may have on how women see sexuality fitting into their lives. It is important to consider these points and not to allow ourselves to be dragged into the medical model. We should look at the importance of the different roles that women have in their lives and how they prioritise them.

Many women have several roles—the professional or worker, housewife, mother, daughter, friend, and lover. This last role seems to fade away as the demands of others increase. When a woman meets her first serious partner, she has fewer of these other roles: she may be only a worker and a daughter. In later years, she will have more roles to contend with: she may be a mother and housewife as well. For many women it seems that, as the responsibility of roles increases, the importance of the lover role diminishes.

Looking at these issues can be quite revealing, and an easy way to give structure to this is to undertake a process that we can call the “timetable of life.” Both partners in the relationship are asked to fill in a timetable representing a typical week. They are then asked to look at the week in terms of time spent in different categories: family time (that is, with children and partners), work time (both at work and work in the house), extended family time (with parents and relations), social time, personal time, and relationship time (time spent together alone, as a couple). This last category is, of course, the time when sexual activity is more likely to be realised successfully.

A timetable almost always shows the elements missing to be relationship time and personal time. Roles are, of course, not just about the practicalities of who does what but about the responsibilities a woman feels for the roles she takes on.

It is useful to ask a woman her views on her learning about sexuality and the influences that have played a part in the development of her sexuality. Sexual learning and role prioritisation are often intertwined. An example of this is the woman who found that she had lost sexual desire after the birth of her first child. Discussion showed that she had, not unnaturally, made the responsibility of being a mother a high priority, but coupled with this was the clear message that she had received when learning about her sexuality, that “mothers are not sexual beings.”

Ten myths about sex

In general, a man should not be seen to express certain emotions

In sex, as elsewhere, it is performance that counts

An erection is essential for a satisfying sexual experience

All physical contact must lead to sex

Sex equals intercourse

Good sex must follow a linear progression of increasing excitement and terminate in orgasm

Sex should be natural and spontaneous

On the whole, the man must take charge of and orchestrate sex

A man wants and is always ready for sex

We no longer believe the above myths

*Adapted from Zilbergeld B. Men and sex: a guide to sexual fulfilment. London: Harper Collins, 1995

Many misunderstandings and myths can be acquired during learning about sexuality, such as that a man is always ready and able to have sex, that sex is natural and spontaneous, and that sex equals intercourse. Sexual myths are held by women as well as men.

Repeating the “timetable” for different times in a woman’s life and comparing it during courtship, when sexual desire was probably good, with the timetable for a time when sexual desire was low is useful and shows how priorities change and how this can influence desire for sexual activity.

Looking at what happens in a sexual situation often gives much information about the defences erected when a patient engages in sexual activity. One can look at what turns a patient on and off, how absorbed she becomes in the sexual experience, and whether loss of desire occurs on every occasion or whether it is situational. Areas such as sexual fantasy, masturbation, genital functioning, and contraception can be discussed and give great insight.

Treatment options

An integrated approach to medical and psychological treatments is optimal. Any medical elements of the problem, if present, must be treated to achieve a positive outcome. In secondary loss of desire for sexual activity, a psychogenic aspect often remains after the medical elements have been treated.

Diagnostic checklist for women’s loss of sexual desire

| • Physical illness | • Psychological characteristics |

| Integrity of anatomy | • Relationship issues |

| Integrity of vascular system | • Life changes |

| Integrity of neurological system | • Sexual history |

| Integrity of endocrine system | • Sexual knowledge |

| • Drugs and treatments | • Attraction to partner |

Most of the treatment will involve cognitive behavioural approaches and psychodynamic approaches based on the discussions previously described. One of the most difficult areas to approach and deal with is loss of attraction for the partner, which can lead to serious difficulties and consequences.

Working with people as a couple when there is loss of sexual desire allows both partners’ understanding of the problem to be examined by means of some of the techniques described above. As partners begin to realise that they can no longer assume that they know how their partner feels, or should feel, the differences in sexuality and sexual needs can be explored. We expect our partners to feel the same way as we feel and to know when we feel sexual. We expect them to be able to provide for our needs sexually without necessarily discussing them. With counselling, the aim is to encourage acceptance of difference, a concept sometimes described as “benign variation.”

Frigidity does not feature in this discussion, nor does it feature in any classification of female sexual dysfunction. The term is more a reflection of women’s feelings about themselves or of men’s feelings about women. When a woman describes herself as frigid, she is really describing how she feels about herself as a sexual being, and it is often a comparison with her or others’ expectations of how she should feel and be. Frigidity is not a medical term, and we should no longer use it.

Further reading

Bancroft J. Human sexuality and its problems. 3rd ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1998

Kaplan HS. The sexual desire disorders. New York: Brunner Mazel, 1995

Hawton K. Sex therapy. A practical guide. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1985 (reprinted 1997)

Kitzinger S. Women’s experience of sex. London: Penguin Books, 1985

Crowe M, Ridley J. Therapy with couples. Oxford: Blackwell Science, 1990 (reprinted 1996)

Heiman J, LoPiccolo L, LoPiccolo J. Becoming orgasmic. A sexual growth programme for women. New Jersey: Spectrum Books, 1976

Dickson A. The mirror within. London: Quartet Books, 1985 (reprinted 1997)

Goodwin AJ, Agronin ME. A woman’s guide to overcome sexual fear and pain. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications, 1997

Masters WH, Johnson VE. Human sexual inadequacy. Boston, MA: Little, Brown, 1970

Figure.

The normal female sexual response. (Adapted from Masters WH, Johnson VE. Human sexual response. Boston, MA: Little, Brown, 1966)

Figure.

As a woman takes on the roles of mother and housewife, the importance of the lover role may diminish

Figure.

We expect our partners to feel the same way as we feel and to know when we feel sexual. (Callipygous Eve and Adoring Adam (1510) by Albrecht Dürer)

Acknowledgments

The picture of a couple lying in bed is reproduced with permission of Tony Stone Images. The picture of a mother and baby is reproduced with permission of Mother & Baby Picture Library.

Footnotes

Josie Butcher is a general practitioner in Nantwich, clinical course director of the MSc in psychosexual therapy, University of Central Lancashire, and honorary lecturer in human sexuality, Withington Hospital, Manchester.

The ABC of sexual health is edited by John Tomlinson, physician at the Men’s Health Clinic, Winchester and London Bridge Hospital, and formerly general practitioner in Alton and honorary senior lecturer in primary care at University of Southampton.