Abstract

Due to extended transitions to adulthood and declining marital rates, bonds between adults and parents have grown increasingly salient in individuals’ lives. This review organizes research around these topics to address ties between parents and grown children in the context of broader societal changes over the past decade. Literature searches included tables of contents of premier journals (e.g., Journal of Marriage and Family), Psychological Info, and Google Scholar. The literature review revealed patterns of social and intergenerational changes. Technological advances (e.g., introduction of the smart phone) co-occurred with more frequent contact and interdependence between generations. The Great Recession and financial strains altered the nature of many parent/child ties, including increased rates of intergenerational coresidence. Individual life problems such as divorce, addiction, and physical health problems were reflected in complex changes in positive and negative relationship qualities, ambivalence, and intergenerational support. Government policies reflect societal values and in turn, affected the distribution of parents’ and grown children’s resources. Political disruptions instigated migration, separating generations across large geographic regions. Political disruptions instigated migration, separating generations across large geographic regions. Demographic changes (e.g., constellation of family members, delayed marriage, same sex marriage) were also manifest in ties between adults and parents. Findings were consistent with the Intergenerational Systems in Context Model, which posits that societal transformations co-occur with changes in intergenerational relationships via reciprocal influences.

Keywords: adult development, ambivalence, immigration/migrant families, intergenerational relationships, intergenerational transfers, social support

Social science is intended to be prescient and predict the course of societal change. Vern Bengtson did just that in his 2001 Journal of Marriage and Family article, foreseeing the rise in salience of intergenerational ties in the 21st century (Bengtson, 2001). Bengtson argued that demographic changes in longevity and in family structures would result in a primacy of intergenerational ties over other relationships. Due to a variety of societal changes, Bengtson’s predictions have borne true: Ties between adults and parents are now more common than any other relationship in adulthood. Although data are not available regarding the prevalence of parent–adult child ties throughout the population, 98% of U.S. adults aged 25 to 32 years report that they have regular contact with at least one parent (Hartnett, Fingerman, & Birditt, 2018). Furthermore, consistent with Bengtson’s predictions, during the past 15 years, individuals are at greater risk of lacking a romantic partner due to diminished rates of marriage, stable (relatively high) rates of divorce, and delayed first marriages; these changes have generated greater involvement between adult offspring and parents. Indeed, a tie to a parent or grown child may be the most important relationship in many adults’ lives. Consequently, this relationship deserves the research attention that marriage has received in the past.

As defined in the family literature, intergenerational ties involve the bonds between the adults of different generations and their progeny: midlife parents and young adult offspring, aging parents and midlife adult offspring, grandparents and grandchildren, and even great grandparents and great grandchildren. This decade review covers publications from 2008 to 2019 addressing ties between adults and their parents. We focus on the parent–child bond because it serves as the key link in intergenerational families, that is, grandparent–grandchild ties are built on parent–child ties (Monserud, 2008, 2010).

In this review, we differentiate between young adults and parents and midlife adults and parents. The past 30 years have seen shifts in the nature of early adulthood with 18- to 34-year-olds increasingly dependent and interconnected with their parents throughout much of the developed world (Arnett, 2009; Furstenberg, 2010). These changing patterns have rendered ties between young adults and their parents distinct from relationship dynamics observed later in adulthood and old age (Fingerman, Huo, Kim, & Birditt, 2017; Furstenberg, Hartnett, Kohli, & Zissimopoulos, 2015). Furthermore, midlife adults often support both young adults and aging parents, and aging parents are often involved in supporting their midlife offspring and grandchildren (Fingerman et al., 2011; Huo, Graham, Kim, Birditt, & Fingerman, 2019; Huo, Kim, Zarit, & Fingerman, 2018). We consider parent–offspring ties prior to the onset of intensive caregiving, noting that caregiving is addressed in a distinct literature (for reviews of the caregiving literature, see Carr & Utz, 2020; Zarit & Zarit, 2015).

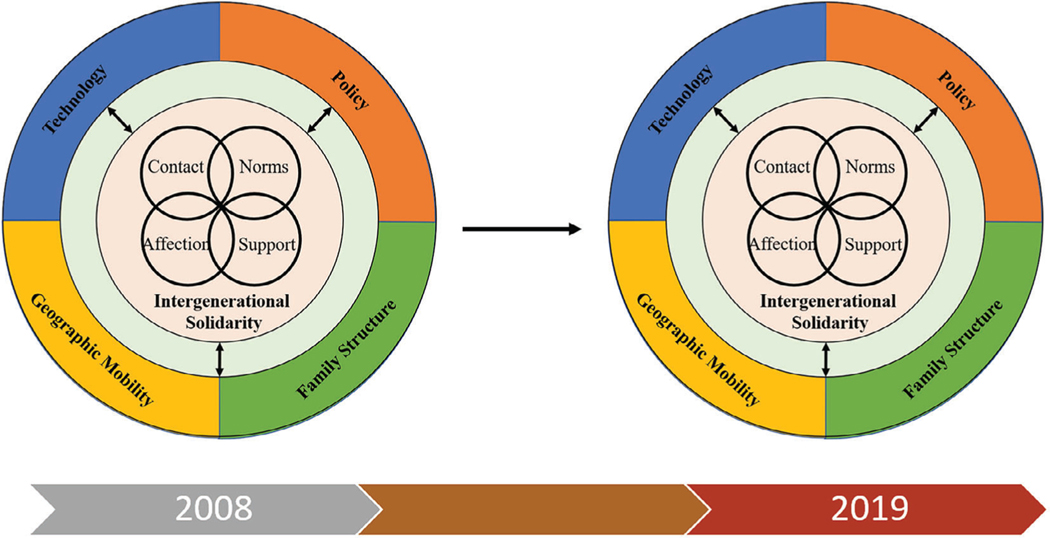

We draw on the intergenerational systems in context model (ISC model; see Figure 1) to consider how macrolevel factors may be associated with microlevel processes in parent–child ties. In examining adult intergenerational ties, the model draws on ecological systems theory (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2006), life course theory (Elder, 1998; Elder, Johnson, & Crosnoe, 2003, 1998), solidarity theory, intergenerational ambivalence theory (Bengtson & Oyama, 2010; Fingerman, Sechrist, & Birditt, 2013), and the family stress model (Conger, Conger, & Martin, 2010). These theories propose interrelated processes between macrolevel societal factors and familial processes. Indeed, scholars have referred to “linked lives” to describe the reciprocal influences between adults and parents (e.g., Greenfield & Marks, 2006). This article attempts to flesh out these models with a specific focus on intergenerational ties. We highlight the ways in which research during the past decade illuminates the associations between macrolevel societal changes and intergenerational processes. We also point out significant gaps in the literature regarding associations between macrolevel phenomena and family processes that should be addressed in future research.

Figure 1.

Intergenerational Systems in Context Model.

Macrolevel factors specified in the ISC model include large societal disruptions during the past decade that are associated with patterns in parent–adult child ties. Technological, economic, political, and demographic changes permeate family life. For example, the past decade has witnessed widespread use of smartphones (introduced by Apple [Cupertino, CA] in 2007) and social media, the onset and recovery from the Great Recession (with many families left behind), persistent elevated rates of immigration worldwide (United Nations, 2017), and changes in societal recognition of diverse families (e.g., legalization of same-sex marriage in many countries). The relationships between adults and parents are embedded with and show bidirectional associations with these transformations.

The model addresses the implications of these societal trends on outcomes outlined in the intergenerational solidarity model and the intergenerational ambivalence model (Bengtson & Oyama, 2010; Fingerman et al., 2013; Silverstein & Giarrusso, 2010). The solidarity model takes a mechanistic view of intergenerational relationships that reflects interconnections between contact, emotions (e.g., affection, conflict, ambivalence), norms or values, and behaviors (e.g., support exchanges; Silverstein, Conroy, & Gans, 2012). Ambivalence theory suggests that, due to competing needs for independence and connection, intergenerational relationships can be simultaneously close as well as irritating. Integrating life course theory, solidarity theory, and ambivalence, we consider these dimensions of intergenerational ties in association with societal shifts.

The ISC model does not make causal arguments. Rather, the associations between family life and societal changes are interrelated. For example, we do not propose that iPhones (Apple) caused increased contact between generations but, rather, co-occurred with changes in family life. A device such as the iPhone could have been applied to many purposes, but apps have been designed to respond to the needs and desires for family contact. Indeed, in several instances, evolving norms appear to have contributed as much to shifts in intergenerational ties as technologies or economic events. Here, we synthesize extant literature on intergenerational ties within a framework of events in the past decade.

Technologies and Contact between Adults and Their Parents

When the past decade review on parents and children went to press (e.g., Umberson et al., 2010), people were still using cell phones to talk to people rather than smartphones to take selfies. Thus, there was very little texting and no Facetime or other video-chatting capabilities. Social media were scant (e.g., Facebook had recently replaced MySpace, and Snapchat and Instagram were still being perfected by computer programmers).

Across this decade, cell phone use reached near saturation among U.S. adults, with 100% of adults aged 18 to 29 reporting that they used a cell phone (Pew Research Center, 2018). As of 2018, 95% of Americans overall reported owning a cell phone and 77% had smart phones; those rates were much lower for adults older than age 65, where only 80% owned a cell phone and 46% owned a smart phone (Anderson & Perrin, 2017; Pew Research Center, 2018) We saw a surge in text messaging (Stern, 2012) followed by a decline in texting with the advent of messaging services (e.g., imessage, WhatsApp) and technology-facilitated face-to-face communication (e.g., Facetime, Skype) among younger adults (Statista, 2018).

The use of text and other digital forms of communication may serve to enhance what Peng et al. (2018, p. 159) refer to as “digital solidarity.” Digital solidarity builds on the premise of associational solidarity by fostering relationship strength through contact (Bengtson & Oyama, 2010; Fingerman et al., 2013; Silverstein & Giarrusso, 2010). Indeed, new technologies have facilitated contact between social partners in general (Cotten, McCullough, & Adams, 2012), and the same may be true of adults and parents. One large study focused on adults’ (aged 18–83) contact with living mothers. The researchers used country-level data from 24 nations collected in 2001, during a period with variability in cell phone adoption (from Russia, where five of 100 persons used mobile phones, to Italy, where 90 of 100 did). In countries with greater mobile phone use, adult offspring (particularly daughters) reported more frequent contact with mothers (Gubenesky & Treas, 2016). As the data were country level and correlational in nature (i.e., more cell phone users in the country, more people reporting frequent contact with parent or child), it is not clear whether the communication occurred via the cell phone technology.

The use of technology also fits into a broader historical trend in contact between adults and parents. Contact has certainly become more frequent during the past 2 decades in the United States, but the shifts predate the widespread use of cell phones. Prior work documented a steady uptick in contact between young adults and parents dating back to the 1990s (Fingerman, Cheng, Tighe, Birditt, & Zarit, 2012). That prior uptick may have reflected declining prices for long-distance phone calls and airline deregulation. The persistent trajectory also reflects the prolonged transition to adulthood during the past 20 years (e.g., higher education, delay partnering) that fosters interdependency among adults and parents (Fingerman et al., 2017; Furstenberg et al., 2015). As such, younger generations today report contact at least once a week or even daily. In a diary of intergenerational ties, nearly all (96%) midlife parents (aged 45–65) had contact with a grown child that week either in person, by phone, or by text; on average, they had contact on three quarters of study days (Fingerman, Kim, Birditt, & Zarit, 2016).

Although the advent of increased contact predates mobile technologies, these technologies are associated with increasing frequency of contact. A study conducted prior to 2010 revealed that adult children never or rarely communicated with parents via electronic technologies (Antonucci, Ajrouch, & Manalel, 2017). Likewise, from 2008 to 2011, slightly less than one third (31%) of older mothers had either texted or emailed a grown child in the past year. Newer data obtained from better-educated mothers in 2016 found that 95% of mothers reported instant messaging or emailing a grown child (Peng et al., 2018).

Thus, research during the past decade suggests that technological advances are associated with altered forms and frequency of contact between generations. The ISC model proposes that these associations are likely bidirectional. New technologies could have been adapted to many purposes (and indeed were), but the development of communication capacities partially reflects ongoing trends and values for being in touch with friends and family, including parents and grown children. Furthermore, changes in the forms of communication may be associated with changes in the affective qualities of the relationship (affection, ambivalence, conflict) as well as shifts in the nature of support exchanges. In the 1980s, a young adult might call parents on Sunday evenings and talk for an hour, discussing the week’s events. But in the 2010s, parents and young adults texted or talked in small moments throughout the day. This frequent contact introduces opportunities for parents and children to influence one another’s mood and stress reactions in the moment (Birditt, Kim, Zarit, Fingerman, & Loving, 2016; Birditt, Manalel, Kim, Zarit, & Fingerman, 2017) and warrants research attention.

A Recession, Financial Difficulties, and Other Problems Adults and Parents Incur

The Great Recession was one of the biggest events in the past century. The Recession started in 2007, but was only widely recognized by the general public in 2008. This global financial downturn shaped intergenerational ties, fostering closeness and tensions in the ties. Moreover, less well-off families lagged in the recovery, exacerbating economic disparities for ethnic and racial minority families (Cynamon & Fazzari, 2016; Kochhar & Fry, 2014). These financial disparities generated risks for young adults and families regarding access (or lack of access) to education (Albertini & Kohli, 2012; Henretta, Wolf, van Voorhis, & Soldo, 2012; Swartz, McLaughlin & Mortimer, 2017), rates of coresidence (Lei & South, 2016), patterns of support (Fingerman et al., 2015), and likelihood of and timing of disability and dementia in late life, necessitating caregiving (Chatterji, Byles, Cutler, Seeman, & Verdes, 2015). Adults and parents may be sensitive to these types of problems in one another’s lives.

The family stress model considers the distress generated within the family when parents of young children incur financial difficulties; the parental stress is transmitted to the children directly via parental behaviors toward the child and directly via repercussions of spousal conflict (Conger et al., 2010). The ISC model draws on this premise by proposing links between societal microlevel events and processes within family, yet the family stress model has not been directly applied to adult generations.

Nevertheless, research regarding intergenerational ties suggests that the influence of financial difficulties and other adverse life events (e.g., divorce, health problems, victim of a crime) on well-being. Adverse events in one generation are associated with stress outcomes across generations of families including young adult (Fingerman, Cheng, Birditt, & Zarit, 2012; Kalmijn & De Graaf, 2012) and midlife offspring (Bangerter, Zarit, & Fingerman, 2016; Gilligan, Suitor, & Pillemer, 2013; Pillemer, Suitor, Riffin, & Gilligan, 2017; Suitor et al., 2016).

Emotional Qualities of Relationships and Life Problems

As suggested by the family stress model, a variety of life problems (e.g., divorce, health problems, addiction, incarceration) affect qualities of the parent–child tie in adulthood. Research examining financial problems typically has focused on the grown child’s financial distress (Gilligan et al., 2013). For example, Hammersmith (2018) used national data from the Health and Retirement Study to document tensions between grown children and older parents if the child lost a job or moved back home.

Other research portrays relationships as more complicated (with a mixture of positive and negative sentiments) when grown children suffer life problems or fail to live up to expected norms. Dating back two decades, researchers introduced the concept intergenerational ambivalence to describe complex feelings that parents and grown children may experience in this tie (Connidis, 2015; Giardin et al., 2018; Lendon, 2017; Luescher & Pillemer, 1998). Researchers have measured intergenerational ambivalence in a variety of ways (Carr & Utz, 2020), including direct measures (i.e., feeling conflicted or torn in a relationship with a grown child or parent), qualitatively in open-ended questions (Verma & Satayanarayana, 2013), and indirectly as a combination of ratings of positive and negative sentiments (Pillemer, Munsch, Fuller-Rowell, Riffin, & Suitor, 2012; Suitor, Gilligan, & Pillemer, 2011). The indirect approach is the most common; a plethora of studies in the past decade have examined a combination of sentiments to assess intergenerational ambivalence (Birditt, Fingerman, & Zarit, 2010; Kiecolt, Blieszner, & Savla, 2011). Yet, one comparison of the two methods suggested that the direct method was better for assessing ambivalence among sons (Suitor et al., 2011). One study examining the indirect approach of asking about both positive and negative sentiments suggested that the negative component of ambivalence accounted for associations between ambivalence and well-being (Gilligan, Suitor, Feld, & Pillemer, 2015). Thus, the measurement of ambivalence warrants research attention in the next decade.

Many studies addressing intergenerational ambivalence in the past decade have focused on parental distress and love for their grown children who suffer different types of problems. For example, Ingersoll-Dayton et al. (2011) presented qualitative data from 22 older mothers who had seriously mentally ill daughters. Mothers described conflicted feelings of love and understanding about their daughters’ troubles, with simultaneous frustration and a desire for their daughters’ greater independence. Kiecolt et al. (2011) tracked parental ambivalence toward children in a general sample as the children transitioned from adolescence through young adulthood for 14 years. Parental ambivalence remained elevated for grown children who had suffered life problems in adolescence (e.g., running away from home, troubles with the police, being expelled, or other behavioral problems). Birditt et al. (2010) examined more than 600 parents who reported on multiple children. Parents experienced increased tensions toward a young adult who incurred life problems, but reported comparable affection for children with problems as their more successful siblings. Using the same dataset, Fingerman, Cheng, Birditt and Zarit (2012) found midlife parents experienced poorer well-being when at least one adult child experienced a life problem, even if the other grown children were faring well.

Researchers also have documented parents’ greater ambivalence and poorer well-being when grown children have failed to achieve life markers of success such as completing education or securing a job (Kalmijn & De Graaf, 2012; Pillemer et al., 2012). These patterns are found in different cultural groups. For example, Pei and Cong (2016) reported that Mexican American parents experienced greater ambivalence when their children were not married or when sons had less education. Nevertheless, adult markers are not deterministic. Kiecolt et al. (2011) found that ambivalence was only associated with nonmarital status, not other adult statuses.

Regarding offspring’s ambivalence toward aging parents, most research has focused on the parent’s late-life physical declines and spousal loss rather than broader social issues such as the Recession or other life crises (Igarashi, Hooker, Coehlo, & Manoogian, 2013). For example, Ha and Ingersoll (2008) found that relationships between parents and adults became less ambivalent immediately after a parent was widowed. The effects of widowhood on relationship qualities diminished after 18 months. A few studies have shown midlife children experience distress for a wide array of parents’ life problems (e.g., addiction, divorce; Bangerter et al., 2016), and daughters in particular experience such distress when they give high levels of support (Bangerter et al., 2018; Bangerter, Polenick, Zarit, & Fingerman, 2018). Cultural norms may contribute to how parental transitions affect relationship qualities. Chen (2017) examined decisions to place older adults in skilled nursing care facilities in Shanghai and found that discrepancies in beliefs about filial piety (the Asian ideal of caring for parents) affected parental relationship distress. Overall, problems experienced among both younger and older generations affect relationship quality and well-being in the broader social and cultural contexts in which those problems occur.

Support Exchanges in Response to Parent or Offspring Problems

Financial contingencies, life problems, and cultural norms also contribute to intergenerational support patterns. Midlife adults give more to their grown children than to their aging parents (unless the parents incur disability; Fingerman et al., 2011). Indeed, Kornrich and Furstenberg (2013) found that on average, parents give 10% of their income to young adult children, regardless of their own socioeconomic position or disposable income. In late life, most parents with higher income intend to leave some sort of bequest to their grown children, but many grown children were unaware of their parents’ intentions and do not expect to receive such an inheritance (Kim, Eggebeen, Zarit, Birditt, & Fingerman, 2013).

Furthermore, parents respond to other life problems that adult offspring incur (Fingerman, Miller, Birditt, & Zarit, 2009; Kalmijn, 2013). Many studies have examined midlife parents who are caregivers of adult children suffering mental health conditions, autism, or developmental delays, although outcomes are often associated with well-being rather than support exchanges (i.e., the support is presumed; Gilligan, Suitor, Rurka, Con, & Pillemer, 2017; Smith & Seltzer, 2012; Song et al., 2014; Taylor, Burke, Smith, & Hartley, 2016). In these situations, consistent with the literature on family caregiving in late life, in these situations, social support for the parent and parental attitudes about the young adult matter more than objective burden.

Researchers have considered overarching macrolevel societal changes with regard to offspring life problems. For example, Siennick (2015) used national data to consider the effects of mass incarceration on intergenerational support patterns and found that parents provide more financial assistance to offending young adults than to nonoffending peers or siblings. Interestingly, there has been little research examining parental support of young adults with opioid addiction. Issues such as addiction warrant research attention in the family literature.

Parenting in childhood has intensified in many parts of the world during the past 2 decades (Nomaguchi & Milkie, 2020). Studies also find that parents persist in helping young adults to achieve statuses of adulthood such as completion of education, settling with a partner, or raising young children of their own (Bucx, van Wel, & Knijn, 2012; Fingerman et al., 2009; Swartz, Kim, Uno, Mortimer, & O’Brien, 2011). These findings are consistent with the perspective that parental support during the transition to adulthood has become normative (Fingerman et al., 2017; Furstenberg et al., 2015). Even when midlife adults are in the throes of caregiving or supporting aging parents in decline, they continue to provide for young adult children simultaneously (Friedman, Park, & Weimers, 2015). Nevertheless, as parents themselves incur disabilities, the flow of support may shift toward parental receipt of support (Hogerbrugge & Silverstein, 2015; Huo, Graham, Kim, Zarit, & Fingerman, 2018; Kim, Fingerman, Birditt, & Zarit, 2016).

Giving and receiving support in response to problems may affect a parent’s or grown child’s well-being. For example, research conducted in the Netherlands found that midlife parents derive emotional benefits from serving in the grandparent role and providing child care for grandchildren (Geurts, Poortman, & van Tilburg, 2012). Likewise, Huo et al. (2019) reported that providing daily support may mitigate distress for aging parents regarding a midlife child’s problems in the United States. These patterns in the United States (and other countries) may be conditioned on racial and ethnic differences, however. Cichy, Stawski, and Almeida (2014) found that providing daily support to family members (including parents and grown children) was associated with poorer well-being for African Americans on a daily basis, but not for non-Hispanic Whites. Thus, intergenerational support needs to be considered in the context of race and ethnicity.

Popular media and researchers (to some extent) have framed young adults’ dependency on parents as deleterious. Articles about “helicopter parents” insinuate that parents bestow too much attention on young adult children (Nelson, Padilla-Walker, & Nielson, 2015; Segrin, Woszidlo, Givertz, Bauer, & Murphy, 2012). Some research suggests that receiving financial help is associated with poorer well-being for offspring over time (Johnson, 2013). Yet evidence also shows that young adults can thrive due to parental involvement, reporting better adjustment and greater likelihood of attaining adult statuses such as completing education (Fingerman et al., 2012; Swartz et al., 2017). Indeed, parental involvement throughout adulthood is considered normative in many places in the world (Nesteruk & Marks, 2009; Newman, 2013). Western cultures may be suffering from a “cultural lag” where beliefs about generational autonomy have not caught up with family dynamics.

Coresidence Between Adults and Parents

As of 2015, for the first time in U.S. history, young adults were more likely to reside with a parent than with a romantic partner (Fry, 2016; Vespa, 2017). Coresidence reflects macrolevel changes in microlevel patterns within the family. Indeed, it would be oversimplifying to argue that coresidence is simply a reflection of the economy—coresidence also occurs in the context of changes in familial values, family structure (e.g., adults are less likely to be married or partnered), and broader societal constraints.

Coresidence is not monolithic. Researchers differentiate young adults who have never left home (“failure to launch”) from those who have returned home (“boomerang children”; Mitchell, 2011; South & Lei, 2015). Furthermore, coresidence varies across adulthood. The young adulthood pattern typically involves young adults residing with parents: The late-life pattern of coresidence often stems from parental disability or cultural imperatives (Cohn & Passel, 2018). Likewise, 10% of young adults who live with parents in the United States have some type of disability (Barker et al., 2011; Vespa, 2017).

Increases in rates of coresidence co-occurred with the Great Recession. Indeed, cross-national research shows that rates of coresidence correlate with financial constraints such as lack of access to high-paying jobs, rental housing, mortgage, or steady employment (Newman, 2013). Notably, however, in the United States, nearly half of coresident offspring pay rent, and 90% contribute to household expenses (Pew Research Center, 2012).

Values and norms also motivate coresidence. In the United States, coresidence is more common and more accepted in early young adulthood; up to half of the coresident offspring in the United States are students enrolled in higher education (Fry, 2013). Likewise, cross-cultural comparisons find that values (as well as economic circumstances) shape the population likelihood of coresidence. The rates of coresidence in Northern Europe are relatively low, whereas the rates of coresidence in Southern Europe are high; researchers have noted the public policies that contribute to these patterns (Dykstra, 2018; Newman, 2013). Families in Southern European countries value intergenerational coresidence more than families in Northern European countries. For example, in Italy, parents who have higher incomes are more likely to reside with grown children because they make the living arrangements more comfortable (Manacorda & Moretti, 2006).

Within countries, young adults from different ethnic groups vary in their likelihood of residing with parents. A study of the Dutch population revealed that second-generation young adults (i.e., children of Turkish, Moroccan, Surinam immigrants) were more likely to return home than the young adults of parents born in the Netherlands (Gruiuters, 2017). Similarly, within the United States, young adults from ethnic or racial minority groups are more likely to reside with parents than are non-Hispanic White young adults, notwithstanding socioeconomic disparities (Lei & South, 2016). Granted, discrimination may contribute to different economic opportunities for different ethnic groups and as such, the rates of coresidence among ethnic groups may reflect financial rather than cultural differences.

The implications of coresidence for adults’ and parents’ well-being are complex. A diary study compared coresident with noncoresident young adults with regard to their daily experiences with parents and mood; the study found few differences after controlling for in-person contact. The only exception was that coresident offspring were more likely to laugh and share humor with their parents (perhaps coresidence gives opportunities for “inside jokes”; Fingerman et al., 2017).

Having a coresident grown child may generate financial and emotional strains for parents in the United States. Maroto (2017) examined longitudinal data (1994–2012) from more than 4,000 midlife parents and found that in years when they coresided with a young adult child, parents reported diminished financial assets and financial savings. Another study of parents aged 50 to 74 in New Jersey showed that parents reported reduced positive mood and increased negative mood when having an adult child in the home (Gerber, Heid, & Pruchno, 2018). But parents with higher income reported greater psychological distress than parents with lower income (Gerber et al., 2018), suggesting that low-income parents may view the coresidence as more normative and acceptable.

Policies, Cultural Norms, and Intergenerational Exchanges

During the past decade, scholars have been particularly interested in the macro–micro interface between public policies and intergenerational ties (Brandt & Deindl, 2013; Dykstra, 2018). Governments have passed laws in several countries specific to parents and grown children. Nevertheless, it is important to note that behaviors in intergenerational ties are not necessarily caused by public policies but, rather, in democracies, family values may drive those policies. For example, in the United States, where private health insurance is the norm (rather than publicly funded health care), a law in 2010, the Affordable Care Act, required health insurance companies to allow parents to cover grown children up to age 26 under their own insurance policy (U.S. Department of Labor, 2018; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2019a). This law recognized the increased dependence of grown children on their parents that had occurred during the past 20 years (Arnett, 2009; Fingerman et al., 2017; Furstenberg, et al., 2010).

Dykstra (2018) provided an analysis of contact and support between adults and parents and government policies in European countries. For the past 20 years, scholars have conceptualized Northern Europe as a region of weak family ties and Southern Europe as a region of strong family ties (Albertini & Kohli, 2012). Related to these conceptions, Northern European government policies facilitate young adults’ moving into their own abodes (Newman, 2013). Yet, the patterns are not straightforward with regard to government and family support: Northern European parents do support their grown children, sometimes more frequently that Southern European parents (albeit support is more intense and occurs in greater amounts in Southern European countries; Albertini & Kohli, 2012; Dykstra, 2018). Indeed, Brandt and Deindl (2013) examined the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement conducted in 13 European countries. They found that parents were more likely to support their grown children in countries that provided more public assistance to young adults, but the support was less intense (e.g., less money, less time).

Available social services also are associated with tasks that parents and grown children perform. For example, the U.S. government instigated Temporary Assistance for Needy Families in the 1990s, requiring low-income parents to engage in work-related activities at least 30 hours a week (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2019b). Ho (2015) examined single low-income grandmothers from a large U.S. national study to understand the implications of this social welfare policy. With Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, governmental supplements for child care increased. As such, older mothers provided less child care, but increased monetary support so the daughter could pay for child care.

Migration and Support Patterns.

As an offshoot of government policies, political disruptions, and civil unrest, the rates of migration have increased steadily throughout the 21st century, with 258 million international migrants in 2017 (United Nations, 2017). Worldwide, the age of international migrants has increased to a median age of 39.2 in 2017 (although the age of migrants has decreased in low-income countries; United Nations, 2017). As such, many of these migrants have intergenerational ties to living parents or even grown children who may or may not accompany them (Van Hook & Glick, 2020). Scholars have noted that in poorer countries, older generations often are left behind while younger generations migrate to locales that are more prosperous.

The implications of these migration trends are unclear. Countries such as Moldova anticipate pension problems and difficulties providing social services, but it is not clear whether older adults suffer due to absentee children (Cojocari & Cupcea, 2018). Research examining a large national study of older adults in Mexico revealed that aging parents whose children had migrated to the United States reported more loneliness, but their general well-being did not suffer (Yahirun & Arenas, 2018), although a prior analysis with the same dataset had revealed that women and mothers left behind did suffer poorer well-being (Silver, 2011).

Nesteruk and Marks (2009) proposed that technologies may facilitate older generations’ involvement with a younger generation who immigrates if the families are well off. They conducted a qualitative study of married Eastern European immigrants (e.g., Romania, Belarus, Bosnia) in the United States who had a professional career. Well-off immigrants were able to pay to return to Eastern Europe or for grandparents to visit the United States and used technology-facilitated communication in the interim (e.g., Skype, phone calls). Yet immigrants with few financial resources incur separation from family members still residing in the country of origin.

A vast literature has also documented value differences in family between first- and second-generation immigrant families with adolescents (Fuligni, 2001; Juang & Cookston, 2009). Researchers documented such differences in a large sample of immigrant family members (aged 15–83) from Turkey, Morocco, Suriname, the Dutch Antilles to the Netherlands. Consistent with prior research, first-generation individuals reported stronger feelings of family solidarity than did second-generation family members. Yet findings were conditioned on other factors. These differences were particularly strong among older adults and adults who espoused a religious background (particularly Islam; Merz, Özeke-Kocabas, Oort, & Schuengel, 2009).

Research on migrant families has focused on generational differences adjusting to a new majority culture (Hardie & Seltzer, 2016). Within this framework, first-generation immigrants generate tensions by clinging to the old culture, but the goal is akin to Star Trek’s Borg: everyone should be assimilated. It may also be the case, however, that immigrant families influence the majority culture. Since 1990, the vast majority of immigrants to the United States came from Latin American and Asian countries (Migration Policy Institute, 2018), regions that espouse strong ties and interdependence among generations. These trends in migration coincide with increased contact and closeness between generations in the majority U.S. culture (Bengtson, 2001; Fingerman et al., 2016). It is possible that adults who migrated to the United States shaped the majority culture. For example, adults in the majority culture may have envied their coworkers’ engagement with family and adopted the desirable behaviors (much like sushi and cilantro in cooking). Future research should address the bidirectionality of influence between migrant and majority culture, with attention to intergenerational ties.

Within-Country Mobility.

In addition to cross-national migration, within-country migration from rural to urban areas in countries such as China, Thailand, and Mexico also affects parents and grown children (Antman, 2010; Knodel, Kespichayawattana, Saengtienchai, & Wiwatwanich, 2010; Liang, 2016). China has witnessed the largest within-country migration, involving more than 221 million individuals in 2010 (National Bureau of Statistics of China, 2012). Traditional Confucian ideals endorsing commitment and support to parents have been superseded by rapid economic development. Grown children often migrate to urban areas for better employment opportunities and greater economic resources, leaving their parents behind and providing scant support from afar. A longitudinal study tracked more than 1,000 Chinese aging parents and their adult sons in rural China and found that parents received more financial support from sons who had migrated to urban areas than from nonmigrant sons (Cong & Silverstein, 2011). Yet, these parents received less practical help probably due to distance. Furthermore, aging parents with migrant adult children reported more depressive symptoms than aging parents whose children resided nearby (Guo, Aranda, & Silverstein, 2009).

An attempt to address this issue began soon after 2000, with rural families entering formal Family Support Agreements—a contract that encourages adult children to provide support to parents (Chou, 2010). China passed an Elderly Rights Law in2013, requiring grown children to visit their parents once a year (Kim, Cheng, Zarit, & Fingerman, 2015). Yet, to visit aging parents, migrant children must apply for unpaid leave and spend money on train and bus tickets, which may exacerbate the economic hardships in these families. As such, the law appears to be scarcely enforced.

Culture and Intergenerational Support.

Governments and policies partially reflect cultural sentiments in democracies. Furthermore, in the absence of government programs, cultural norms direct support, such as grandparents who provide child care throughout China (Chen & Liu, 2011; Chen, Liu, Mair, 2011) and parents who pay for higher education in countries where governments do not fully support higher education (Henretta et al., 2012).

These patterns of support are also conditioned on gender. A vast literature has shown that daughters play a central role in the matrilineal Western cultures (Fingerman, Huo, & Birditt, 2018; Suitor & Pillemer, 2006; Suitor, Pillemer, & Sechrist, 2006). In Asian countries (e.g., China, Korea, Japan), by contrast, the dominant patrilineal norm renders parents more willing to help their sons and expect sons to reciprocate (Hu, 2017; Kim, Zarit, Fingerman, & Han, 2015). Societal changes in the past few decades (e.g., increased education and income in women) have facilitated the rise of daughters and daughters-in-law in helping parents (Xie & Zhu, 2009). Yet, such changes have had little impact on parental decisions about downstream support. Hu (2017) found that daughters now provide more care to aging parents in China than do sons, but parental norms favoring sons still hold sway and parents provide more support to sons.

Family Forms and Demographic Trends

Family forms in the United States have changed dramatically during the past 2 or 3 decades, but research on intergenerational ties has not kept pace (Seltzer, 2015). We consider the following three issues regarding intergenerational ties: (a) marital histories, (b) lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning (or queer) (LGBTQ) parents and grown children, and (c) estrangement between adults and parents. Notably, research has examined these patterns under a framework of causality or embeddedness, that is, as though changes in family forms have altered the nature of intergenerational ties. In some cases, that is likely true; for example, early life parental divorce contributes to later life weakening of the father–midlife child bond. Other aspects of family demography may reflect alterations in intergenerational bonds as much as cause them. For example, the legalization of same-sex marriage in many countries has altered family forms during the past 10 years, but in much of the population, shifts in parental attitudes towards having a LGBTQ child predate those legal changes. As such, we present these intergenerational phenomena in the context of demographic changes, but recognize bidirectional influences.

Marital History and Parent–Offspring Ties

The likelihood of having married parents in adulthood has decreased during the past few decades. Many of today’s young and midlife adults experienced parental divorce as children (Kennedy & Ruggles, 2014). Since 1990, the divorce rate for individuals aged 55 to 64 has doubled (from five to 11 per 1,000) and among adults older than age 65 it has tripled (from two to six per 1,000; Wu, 2017). Interestingly, the rates of remarriage have been dropping during the past decade, particularly among divorced individuals with some college education (Payne, 2017). As such, the likelihood that parents will be unpartnered has increased during the past decade.

A recent examination of national data from the Health and Retirement Study revealed that more than 40% of midlife adults and older couples with children were in stepfamilies (Lin, Brown, Cupka, & Carr, 2018). The patterns were complex, with more disadvantaged couples likely to be cohabiting and to have children from their prior marriages, whereas advantaged couples were more likely to be married and have joint children as well as stepchildren.

These variations in family structure have implications for intergenerational ties. Step-family members are less likely to live near one another and are less likely to coreside (Seltzer & Bianchi, 2013), and parents in stepfamilies have less contact with their biological children than parents in intact families (van der Pas & van Tilburg, 2010). Older parents receive less support from stepchildren (Pezzin, Pollak, & Steinberg Schone, 2008) and have poorer relationships with stepchildren (R. A. Ward, Spitze, & Deane, 2009) than with biological children. When divorced fathers repartner, contact and support exchanges with adult children decrease even further (Noel-Miller, 2013). Nevertheless, Arranz and colleagues (2013) found that older adults had closer ties with stepchildren in relationships of longer duration and when older parents endorsed greater familism (van der Pas, van Tilburg, & Silverstein, 2013).

In addition, adult children’s marital status and history also influence the parent–child relationship. Never-married children have the most frequent contact and exchanges with their parents (Fingerman et al., 2009; Kalmijn, 2016). Furthermore, when compared with married children, divorced children have more frequent contact (Sarkisian & Gerstel, 2008) and are more likely to coreside with parents (Kalmijn, 2016).

Overall, the marital status of both parents and grown children shape their intergenerational ties. These patterns likely will become even more complex as new generations of families are introduced and have their own complex marital histories.

LGBTQ Adults and Intergenerational Ties

Approximately 4% of adults in the United States identify as lesbian gay or bisexual, and 0.6% are transgender (Flores, Herman, Gates, & Brown, 2016; Gates, 2014). The past decade saw numerous shifts in laws and norms that affect these populations. Same-sex marriage became legal in the United States in 2015 and was also recently legalized in many other countries (e.g., Argentina 2010, Australia 2017, Denmark 2012, Germany 2017, England 2013, New Zealand 2013, Taiwan 2019; Pew Research Center, 2017). Research has documented a general positive shift in attitudes toward sexual and gender minorities (Russell & Fish, 2019). At the same time, discrimination is persistent, and indeed, many legal protections for LGBTQ individuals have been removed (Veldhuis, Drabble, Riggle, Wootton, & Hughes, 2018).

An adult child identifying as LGBTQ may shape the tie with the parent. Some scholarship suggests LGBTQ adult children’s ties to their parents are emotionally fraught. Early work on this topic focused on whether grown children had disclosed that they were in a same-sex relationship to the parent (LaSala, 1998). More recent work has focused on situations where both parties are aware of the LGBTQ adult’s identity. Parents report greater feelings of ambivalence toward their children who are LGBTQ (Reczek, 2016a) and may simultaneously worry about and love their LGBTQ children (Connidis, 2012). Parental rejection is often associated with underlying beliefs and values (Jones, Cox, & Navarro-Rivera, 2014), and disapproval of LGBTQ identity is associated with greater parent–child relationship strain (Reczek, 2016b).

Yet, it is not necessarily the case that LGBTQ adults have tense relationships with their parents. A majority of parents in 2015 indicated that they would not be at all upset if their child were gay, and Reczek (2014) found that the majority of LGBTQ individuals report a supportive tie with at least one parent or parent-in-law. Research using the German Family Panel shows that LGBTQ adults’ relationships with parents are similar to those of straight adult children. Although gay and lesbian adult children reported less closeness to both parents and less contact with fathers than straight children, there were no variations in geographic proximity or tensions with either parent (Hank & Salzburger, 2015). There is likely a great deal of variation in these ties, depending on parental beliefs and values as well as the broader cultural context.

Surprisingly, there is almost no research examining LGBTQ parents’ relationships with their grown children. If the parent was open throughout the child’s life (e.g., two same-sex parents) or acknowledged their own sexual identity later, we do not know how that affected the relationship with the child.

Estrangement and Loss of Intergenerational Ties

The topic of estrangement or lacking ties to a parent or grown child has received increased attention during the past decade. The pervasiveness of estrangement depends on the definition. One study found that 62% of older mothers reported contact less than once a month with at least one grown child. Disparities in values typically differentiated that child from siblings (Gilligan, Suitor, & Pillemer, 2015). Estrangement of this type also may reflect structural factors associated with these value differences. For example, in some cases, LGBTQ adults may distance themselves from parents to cope with that disapproval (Reczek, 2016b). Estrangement between LGBTQ adult children and their parents is not well documented, although popular media and news accounts suggest that some parents reject LGBTQ youth at the time they disclose their identity. Additional research is needed to understand these patterns.

Using a more stringent criterion of little or no contact at all, Hartnett et al. (2018) examined a national sample of adults aged 25 to 32 who lacked a mother figure or lacked a father figure all together. Nearly 20% of young adults lack a father figure in the United States—typically because their father was deceased, they never had a father figure, or the father was incarcerated. A smaller proportion lacked a mother figure (6%) primarily due to maternal death.

Loss of ties to a living parent or grown child also is confounded with race. Goldman and Cornwell (2018) examined two waves of data (2005–2006 and 2010–2011) from a large national study of older adults aged 57 to 85. They tracked whether parents named each grown child as a confidant across the 5 years. Black older adults and disadvantaged older adults reported more frequent contact with child confidants at Wave 1, but also were almost twice as likely as White older adults to exclude a child confidant from Wave 2 named at Wave 1. This instability in child confidants seemed to reflect residential moves by one or both parties (which may reflect financial difficulties and job loss).

The early loss of child or parent to death further reflects racial discrimination in the United States. The past decade saw the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement founded in 2013 in response to lethal police violence against innocent Black young men. Early deaths in the Black community are widespread and may have profound implications for family members. Umberson et al. (2017) analyzed racial differences in two national datasets: the National Longitudinal Study of Youth and the Health and Retirement Study. When compared with non-Hispanic White Americans, Black Americans were twice as likely to enter young adulthood having lost a parent to death and more than twice as likely to experience loss of a child during adulthood. These disparities in death rates generate extreme stress and health disadvantages (Umberson, 2016).

Future Research on Intergenerational Ties for the 2020s: What We Know (and Do Not Know) About Ties Between Adults and Parents

Family science has advanced an understanding of intergenerational ties regarding contact, support, and feelings, and this review suggests bidirectional associations between these aspects of relationships and historical and societal changes. Despite decades of head nodding to life course and ecological theories, many studies on intergenerational ties examine (a) behaviors and qualities of this tie devoid of larger context or (b) historical period with regard to the economy or policy, but primarily with regard to tangible support (e.g., finances, coresidence, child care) and without consideration of family values and social norms. Future research should continue to examine intergenerational ties in the context of societal transformations.

It is possible that some aspects of the microcosm of family life for adults and parents transcend historical events and societal disruptions; families navigate divorce, health problems, and other life crises regardless of the broader social context. Yet, theories in family science suggest that we should pay greater attention to technical, economic, policy, and demographic changes (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2006; Elder et al., 2003), and this review supports such theories.

Future Research Methods and Approaches to Understand Intergenerational Ties

Future research might also advance an understanding of intergenerational ties by applying approaches and designs that have gained traction in the past decade. For example, several studies have generated typologies of intergenerational ties (e.g., latent class analysis) in different countries including European nations, Israel, and Korea (e.g., Dykstra & Fokkema, 2011; Kim, Zarit et al., 2015; Kim, Fingerman, Birditt, & Zarit, 2016; Silverstein, Gans, Lowenstein, Giarrusso, & Bengtson, 2010). Typological analyses capture the nuances and complexities of intergenerational relationships and present combinations of relationship qualities or support patterns that differentiate families. Several of these analyses also have considered political and economic forces that may explain variability in family types. Future studies might consider the ICS model to link changes in family classifications over time to macrolevel factors (e.g., economic, political) and microlevel or family-level factors (e.g., changes in family members due to death or relationship dissolution, health problems, or individual life crises) that drive these changes.

Limited sources of data also prevent challenges for understanding parent–adult child ties. Many important contributions in the past decade regarding intergenerational ties relied on large national studies such as The National Longitudinal Study of Youth and the Health and Retirement Study (Hammersmith, 2018; Ho, 2015; Umberson et al., 2017). These studies include an impressive array of topics, but the measurement of intergenerational ties is scant. As such, secondary analyses provide only a cursory understanding of the lived experience of adults and parents. Three longitudinal studies in the late 20th and early 21st centuries focused specifically on intergenerational ties: Longitudinal Studies of Generations, Family Exchanges Study, and Within-Family Differences Study (for a description of these studies, see Suitor et al., 2018) and provided insights into a greater variety of experiences in this tie such as within family differences among siblings and daily experiences. A deeper understanding of family life in the next decade will require additional studies that delve in depth into intergenerational relationships, beyond the large-scale national studies that capture a wide array of topics.

Qualitative research also disentangles the nuances of relationships between adults and parents. Indeed, Sechrist, Suitor, Riffin, Taylor-Watson, and Pillemer (2011) demonstrated that combining quantitative methods with qualitative analyses provided inferences into null findings regarding racial differences in mothers’ preferences for different children. The qualitative data revealed that despite apparent racial similarity, Black mothers were more likely to emphasize interpersonal dynamics when they described more favored children. Likewise, qualitative data may provide insights into a wide array of other topics such as assumptions about the meaning of trends in family structure and societal events with regard to intergenerational ties. For example, the United States has had a relatively high divorce rate for several decades, but we do not know whether divorce means the same thing in the context of ties to parents today as it did 3 decades ago. Likewise, the United States has a growing maternal mortality rate, and qualitative research might inform an understanding of how the surviving parent or grandparent copes with these losses.

Furthermore, a variety of observational, diary, and ecologically valid methodologies could be applied to intergenerational ties. The marital literature is rife with studies examining conversations, tracking daily moods and exchanges, and observational assessment (Gleason, Iida, Shrout, & Bolger, 2008; Neff & Karney, 2009; Williamson, Karney, & Bradbury, 2013). Given the potential importance of ties to parents and grown children, similar methods are needed to understand the dynamics of these relationships. For example, including Ecological Momentary Assessments via smart phones may shed light on how daily interactions and stress among parents and children are associated with daily well-being. Furthermore, studies could use physiological monitoring to examine links between daily experiences in intergenerational ties and health outcomes such as physical activity, blood pressure, and heart rate as indicators of physiological reactivity to emotional experiences in these ties.

In sum, the past decade has ushered in technical changes that co-occurred with increased contact and dependency between generations. An economic downturn fostered greater dependency among generations. An uptick in coresidence between young adults and parents reflects economic circumstances and also values and norms for such coresidence. Moreover, adults and their parents react to and support government policies by altering the distribution of their own resources. Political disruptions have instigated migration that separates generations across large geographic areas. Demographic factors regarding the constellation of family members, delayed marriage, and same-sex marriage are reflected in qualities of ties between adults and parents in changing family contexts. In the next decade, we will need increasing research attention to adults and their parents in the context of societal changes and the new challenges that arise.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by National Institute on Aging Grant R01AG027769, Family Exchanges Study II (Karen L. Fingerman, principal investigator), and National Institute on Aging Grant R01AG046460, Social Networks and Well-Being in Late Life: A Study of Daily Mechanisms (Karen L. Fingerman, principal investigator). The MacArthur Network on an Aging Society (John W. Rowe, network director) provided funds. This research was also supported by Grant P2CHD042849 awarded to the Population Research Center at The University of Texas at Austin by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Contributor Information

KAREN L. FINGERMAN, University of Texas at Austin

MENG HUO, University of Texas at Austin.

Kira S. Birditt, University of Michigan*

References

- Albertini M, & Kohli M. (2012). The generational contract in the family: An analysis of transfer regimes in Europe. European Sociological Review, 29, 828–840. 10.1093/esr/jcs061 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson M, & Perrin A (2017). Technology use climbs among older adults. Retrieved from Pew Research Center website: http://www.pewinternet.org/2017/05/17/technology-use-among-seniors/

- Antman FM (2010). Adult child migration and the health of elderly parents left behind in Mexico. American Economic Review, 100, 205–208. 10.1257/aer.100.2.205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonucci TC, Ajrouch KJ, & Manalel JA (2017). Social relations and technology: Continuity, context, and change. Innovation in Aging, 1, 1–16. 10.1093/geroni/igx029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ (2009). A longer road to adulthood. In Skolnick AS & Skolnick JH (Eds.), Family in transition (pp. 328–341). London, UK: Pearson Education. [Google Scholar]

- Bangerter LR, Polenick CA, Zarit SH, & Fingerman KL (2018). Life problems and perceptions of giving support: Implications for aging mothers and middle-aged children. Journal of Family Issues, 39, 917–934. 10.1177/0192513X16683987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bangerter LR, Yin L, Kim K, Zarit SH, Birditt KS, & Fingerman KL (2018). Everyday support to aging parents: Links to middle-aged children’s diurnal cortisol and daily mood. The Gerontologist, 58, 654–662. 10.1093/geront/gnw207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bangerter LR, Zarit SH, & Fingerman KL (2016). Moderator effects of mothers’ problems on middle-aged offspring’s depressive symptoms in late life. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 71, 41–48. 10.1093/geronb/gbu081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker ET, Hartley SL, Seltzer MM, Floyd FJ, Greenberg JS, & Orsmond GI (2011). Trajectories of emotional well-being in mothers of adolescents and adults with autism. Developmental Psychology, 47, 551–561. http://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/a0021268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker OA, Salzburger V, Lois N, & Nauck B. (2013). What narrows the stepgap? Closeness between parents and adult (step) children in Germany. Journal of Marriage and Family, 75, 1130–1148. 10.1111/jomf.12052 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bengtson VL (2001). Beyond the nuclear family: The increasing importance of multigenerational bonds. Journal of Marriage and Family, 63, 1–16. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2001.00001.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bengtson VL, & Oyama PS (2010). Intergenerational solidarity and conflict. In Cruz-Saco MA & Zelenev S. (Eds.), Intergenerational solidarity (pp. 35–52). New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Birditt KS, Fingerman KL, & Zarit SH (2010). Adult children’s problems and successes: Implications for intergenerational ambivalence. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 65, P145–P153. 10.1093/geronb/gbp125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birditt KS, Kim K, Zarit SH, Fingerman KL, & Loving TJ (2016). Daily interactions in the parent-adult child tie: Links between children’s problems and parents’ diurnal cortisol rhythms. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 63, 208–216. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2015.09.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birditt KS, Manalel JA, Kim K, Zarit SH, & Fingerman KL (2017). Daily interactions with aging parents and adult children: Associations with negative affect and diurnal cortisol. Journal of Family Psychology, 31, 699–709. 10.1037/fam0000317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt M, & Deindl C. (2013). Intergenerational transfers to adult children in Europe: Do social policies matter? Journal of Marriage and Family, 75, 235–251. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2012.01028.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U, & Morris PA (2006). The bioecological model of human development. In Damon W. & Lerner RM (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 1. Theoretical models of human development (6th ed., pp. 793–828). New York, NY: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Bucx F, van Wel F, & Knijn T. (2012). Life course status and exchanges of support between young adults and parents. Journal of Marriage and Family, 74, 101–115. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2011.00883.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen F, & Liu G. (2011). The health implications of grandparents caring for grandchildren in China. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 67, 99–112. 10.1093/geronb/gbr132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou RJA (2010). Filial piety by contract? The emergence, implementation, and implications of the “family support agreement” in China. The Gerontologist, 51, 3–16. 10.1093/geront/gnq059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cichy KE, Stawski RS, & Almeida DM (2014). A double-edged sword: Race, daily family support exchanges, and daily well-being. Journal of Family Issues, 35, 1824–1845. 10.1177/192513X13479595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohn D, & Passel JS (2018). A record 64 million Americans live in multigenerational households. Retrieved from Pew Research Center website: http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/04/05/a-record-64-million-americans-live-in-multigenerational-households/

- Cojocari T, & Cupcea R. (2018). Aging in Moldova: A country with orphan older adults. The Gerontologist, 58, 797–804. 10.1093/geront/gny055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cong Z, & Silverstein M. (2011). Intergenerational exchange between parents and migrant and nonmigrant sons in rural China. Journal of Marriage and Family, 73, 93–104. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00791.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Conger KJ, & Martin MJ (2010). Socioeconomic status, family processes, and individual development. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72, 685–704. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00725.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connidis IA (2012). Interview and memoir: Complementary narratives on the family ties of gay adults. Journal of Family Theory and Review, 4, 105–121. 10.1111/j.1756-2589.2012.00127.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Connidis IA (2015). Exploring ambivalence in family ties: Progress and prospects. Journal of Marriage and Family, 77, 77–95. 10.1111/jomf.12150 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cotten SR, McCullough BM, & Adams RG (2012). Technological influences on social ties across the lifespan. In Fingerman KL, Berg CA, Smith J, & Antonucci TC (Eds.), Handbook of lifespan development (pp. 647–672). New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Cynamon BZ, & Fazzari SM (2016). Inequality, the great recession and slow recovery. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 40, 373–399. 10.1093/cje/bev016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dykstra PA (2018). Cross-national differences in intergenerational family relations: The influence of public policy arrangements. Innovation in Aging, 2. Advance online publication. 10.1093/geroni/igx032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Dykstra PA, & Fokkema T. (2011). Relationships between parents and their adult children: A West European typology of late-life families. Ageing and Society, 31, 545–569. 10.1017/S0144686X10001108 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elder GH, Johnson MK, & Crosnoe R. (2003). The emergence and development of life course theory. In Mortimer JT & Shanahan MJ (Eds.), Handbook of the life course (pp. 3–19). Boston, MA: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Elder GH Jr. (1998). The life course as developmental theory. Child Development, 69, 1–12. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1998.tb06128.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fingerman KL (2016). The ascension of parent-offspring ties. The Psychologist, 29, 114–117. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fingerman KL (2017). Millennials and their parents: Implications of the new young adulthood for midlife adults. Innovation in Aging, 1, 1–16. 10.1093/geroni/igx026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fingerman KL, Cheng Y-P, Birditt KS, & Zarit SH (2012). Only as happy as the least happy child: Multiple grown children’s problems and successes and middle-aged parents’ well-being. The Journals of Gerontology B, 67, 184–193. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbr086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fingerman KL, Cheng Y-P, Tighe LA, Birditt KS, & Zarit SH (2012). Relationships between young adults and their parents. In Booth A, Brown SL, Landale N, Manning W, & McHale SM (Eds.), Early adulthood in a family context: Vol. 2. National Symposium on Family Issues (pp. 59–85). New York, NY: Springer. 10.1007/978-1-4614-1436-0_5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fingerman KL, Cheng Y-P, Wesselmann ED, Zarit S, Furstenberg FF, & Birditt KS (2012). Helicopter parents and landing pad kids: Intense parental support of grown children. Journal of Marriage and Family, 74, 880–896. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2012.00987.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fingerman KL, Huo M, & Birditt K. (2018). Mothers, fathers, daughters, and sons: Gender differences in adults’ intergenerational ties. Manuscript under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Fingerman KL, Huo M, Kim K, & Birditt KS (2017). Coresident and noncoresident emerging adults’ daily experiences with parents. Emerging Adulthood, 5, 337–350. 10.1177/2167696816676583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fingerman KL, Kim K, Birditt KS, & Zarit SH (2016). The ties that bind: Middle-aged parents’ daily experiences with grown children. Journal of Marriage and Family, 78, 431–450. 10.1111/jomf.12273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fingerman KL, Kim K, Davis EM, Furstenberg FF Jr., Birditt KS, & Zarit SH (2015). “I’ll give you the world”: Parental socioeconomic background and assistance to young adult children. Journal of Marriage and Family, 77, 844–865. 10.1111/jomf.12204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fingerman KL, Pitzer LM, Chan W, Birditt KS, Franks MM, & Zarit S. (2011). Who gets what and why: Help middle-aged adults provide to parents and grown children. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 66, S87–S98. 10.1093/geronb/gbq009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fingerman KL, Sechrist J, & Birditt KS (2013). Changing views on intergenerational ties. Gerontology, 59, 64–70. 10.1159/000342211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores AR, Herman JL, Gates GJ, & Brown TNT (2016). How many adults identify as transgender in the United States? Los Angeles, CA: The Williams Institute.

- Friedman EM, Park SS, & Wiemers EE (2015). New estimates of the sandwich generation in the 2013 panel study of income dynamics. The Gerontologist, 57, 191–196. 10.1093/geront/gnv080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fry R. (2013). A rising share of young adults live in their parents’ home. Retrieved from Pew Research Center website: https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2013/08/01/a-rising-share-of-young-adults-live-in-their-parents-home/

- Fry R. (2015). More millennials living with family despite improved job market. Retrieved from Pew Research Center website: https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2015/07/29/more-millennials-living-with-family-despite-improved-job-market/

- Fry R. (2016). For the first time in modern era, living with parents edges out other living arrangements for 18- to 34-year-olds. Retrieved from Pew Research Center website: https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2016/05/24/for-first-time-in-modern-era-living-with-parents-edges-out-other-living-arrangements-for-18-to-34-yearolds/

- Fuligni AJ (2001). A comparative longitudinal approach to acculturation among children from immigrant families. Harvard Educational Review, 71, 566–578. [Google Scholar]

- Furstenberg FF Jr., Hartnett CS, Kohli M, & Zissimopoulos JM (2015). The future of intergenerational relations in aging societies. Daedelus, 144, 21–40. 10.1162/DAED_a_00328 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gaalen RIV, & Dykstra PA (2006). Solidarity and conflict between adult children and parents: A latent class analysis. Journal of Marriage and Family, 68, 947–960. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2006.00306.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gao G. (2015). Most Americans now say learning their child is gay wouldn’t upset them. Retrieved from Pew Research Center website: http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2015/06/29/most-americans-now-say-learning-their-child-is-gay-wouldnt-upset-them/

- Gates GJ (2014). LGBT demographics: Comparisons among population-based surveys. Retrieved from https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0kr784fx

- Gerber A, Heid AR, & Pruchno R. (2018). Adult children living with aging parents: The association between income and parental affect. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development. Advance online publication. 10.1177/091415018758448 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Geurts T, Poortman AR, & Van Tilburg TG (2012). Older parents providing child care for adult children: Does it pay off? Journal of Marriage and Family, 74, 239–250. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2011.00952.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gilligan M, Suitor JJ, Feld S, & Pillemer K. (2015). Do positive feelings hurt? Disaggregating positive and negative components of intergenerational ambivalence. Journal of Marriage and Family, 77, 261–276. 10.1111/jomf.12146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilligan M, Suitor JJ, & Pillemer K. (2013). Recent economic distress in midlife: Consequences for adult children’s relationships with their mothers. In Claster PN & Blair SL (Eds.), Visions of the 21st century family: Vol. 7. Transforming structures and identities Contemporary perspectives in family research (pp. 159–184). Bingley, UK: Emerald Group. [Google Scholar]

- Gilligan M, Suitor JJ, & Pillemer K. (2015). Estrangement between mothers and adult children: The role of norms and values. Journal of Marriage and Family, 77, 908–920. 10.1111/jomf.12207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilligan M, Suitor JJ, Rurka M, Con G, & Pillemer K. (2017). Adult children’s serious health conditions and the flow of support between the generations. The Gerontologist, 57, 179–190. 10.1093/geront/gnv075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girardin M, Widmer ED, Connidis IA, Castrén AM, Gouveia R, & Masotti B. (2018). Ambivalence in later-life family networks: Beyond intergenerational dyads. Journal of Marriage and Family, 80, 768–784. 10.1111/jomf.12469 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gleason MEJ, Iida M, Shrout PE, & Bolger N. (2008). Receiving support as a mixed blessing: Evidence for dual effects of support on psychological outcomes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 94, 824–838. 10.1037/0022-3514.94.5.824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman AW, & Cornwell B. (2018). Social disadvantage and instability in older adults’ ties to their adult children. Journal of Marriage and Family, 80, 1314–1332. 10.1111/jomf.12503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein JR (1999). The leveling of divorce in the United States. Demography, 36, 409–414. 10.2307/2648063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield EA, & Marks NF (2006). Linked lives: Adult children’s problems and their parents’ psychological and relational well-being. Journal of Marriage and Family, 68, 442–454. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2006.00263.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gubenesky Z, & Treas J. (2016). Call home? Mobile phones and contacts with mother in 24 countries. Journal of Marriage and Family, 78, 1237–1249. 10.1111/jomf.12342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo M, Aranda MP, & Silverstein M. (2009). The impact of out-migration on the inter-generational support and psychological well-being of older adults in rural China. Ageing and Society, 29, 1085–1104. 10.1017/S0144686X0900871X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guo M, Chi I, & Silverstein M. (2012). The structure of intergenerational relations in rural China: A latent class analysis. Journal of Marriage and Family, 74, 1114–1128. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2012.01014.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guo M, Chi I, & Silverstein M. (2013). Sources of older parents’ ambivalent feelings toward their adult children: The case of rural China. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 68, 420–430. 10.1093/geronb/gbt022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzzo KB (2016). Do young mothers and fathers differ in the likelihood of returning home? Journal of Marriage and Family, 78, 1332–1351. 10.1111/jomf.12347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammersmith A. (2018). Life interrupted: Parents’ positivity and negative toward children following children’s and parents’ transitions later in life. The Gerontologist, 59, 519–527. 10.1093/geront/gny013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hank K, & Salzburger V. (2015). Gay and lesbian adults’ relationship with parents in Germany. Journal of Marriage and Family, 77, 866–876. 10.1111/jomf.12205 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hardie JH, & Seltzer JA (2016). Parent-child relationships at the transition to adulthood: A comparison of Black, Hispanic and White immigrant and native-born youth. Social Forces, 95, 321–354. 10.1093/sf/sow033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartnett CS, Fingerman KL, & Birditt KS (2018). Without the ties that bind: Young adults who lack active parental relationships. Advances in Life Course Research, 35, 103–113. 10.1016/j.alcr.2018.01.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hatton C. (2013, July 1). New China law says children “must visit parent.” BBC News, Beijing. Retrieved from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-23124345

- Henretta JC, Wolf DA, van Voorhis MF, & Soldo BJ (2012). Family structure and the reproduction of inequality: Parents’ contribution to children’s college costs. Social Science Research, 41, 876–887. 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2012.02.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho C. (2015). Welfare-to-work reform and intergenerational support: Grandmothers’ response to the 1996 PRWORA. Journal of Marriage and Family, 77, 407–423. 10.1111/jomf.12172 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hogerbrugge MJA, & Silverstein MD (2015). Transitions in relationships with older parents: From middle to later years. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 70, 481–495. 10.1093/geronb/gbu069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu A. (2017). Providing more but receiving less: Daughters in intergenerational exchange in mainland China. Journal of Marriage and Family, 79, 739–757. 10.1111/jomf.12391 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huo M, Graham JL, Kim K, Birditt KS, & Fingerman KL (2019). Aging parents’ daily support exchanges with adult children suffering problems. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 74, 449–459. 10.1093/geronb/gbx079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huo M, Graham JL, Kim K, Zarit SH, & Fingerman KL (2018). Aging parents’ disabilities and daily support exchanges with middle-aged children. The Gerontologist, 58, 872–882. 10.1093/geront/gnx144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igarashi H, Hooker K, Coehlo DP, & Manoogian MM (2013). “My nest is full:” Intergenerational relationships at midlife. Journal of Aging Studies, 27, 102–112. 10.1016/j.jaging.2012.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingersoll-Dayton B, Dunkle RE, Chadiha L, Lawrence-Jacobson A, Li L, Weir E, & Satorius J. (2011). Intergenerational ambivalence: Aging mothers whose adult daughters are mentally III. Families in Society, 92, 114–119. 10.1606/1044-3894.4077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen AC, Whiteman SD, Fingerman KL, & Birditt KS (2013). “Life still isn’t fair”: Parental differential treatment of young adult siblings. Journal of Marriage and Family, 75, 438–452. 10.1111/jomf.12002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]