Abstract

Background

Cellular senescence can have positive and negative effects on the body, including aiding in damage repair and facilitating tumor growth. Adamantinomatous craniopharyngioma (ACP), the most common pediatric sellar/suprasellar brain tumor, poses significant treatment challenges. Recent studies suggest that senescent cells in ACP tumors may contribute to tumor growth and invasion by releasing a senesecence-associated secretory phenotype. However, a detailed analysis of these characteristics has yet to be completed.

Methods

We analyzed primary tissue samples from ACP patients using single-cell, single-nuclei, and spatial RNA sequencing. We performed various analyses, including gene expression clustering, inferred senescence cells from gene expression, and conducted cytokine signaling inference. We utilized LASSO to select essential gene expression pathways associated with senescence. Finally, we validated our findings through immunostaining.

Results

We observed significant diversity in gene expression and tissue structure. Key factors such as NFKB, RELA, and SP1 are essential in regulating gene expression, while senescence markers are present throughout the tissue. SPP1 is the most significant cytokine signaling network among ACP cells, while the Wnt signaling pathway predominantly occurs between epithelial and glial cells. Our research has identified links between senescence-associated features and pathways, such as PI3K/Akt/mTOR, MYC, FZD, and Hedgehog, with increased P53 expression associated with senescence in these cells.

Conclusions

A complex interplay between cellular senescence, cytokine signaling, and gene expression pathways underlies ACP development. Further research is crucial to understand how these elements interact to create novel therapeutic approaches for patients with ACP.

Keywords: adamantinomatous craniopharyngioma (ACP), machine learning, next generation sequencing, pediatric neuro-oncology, senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP)

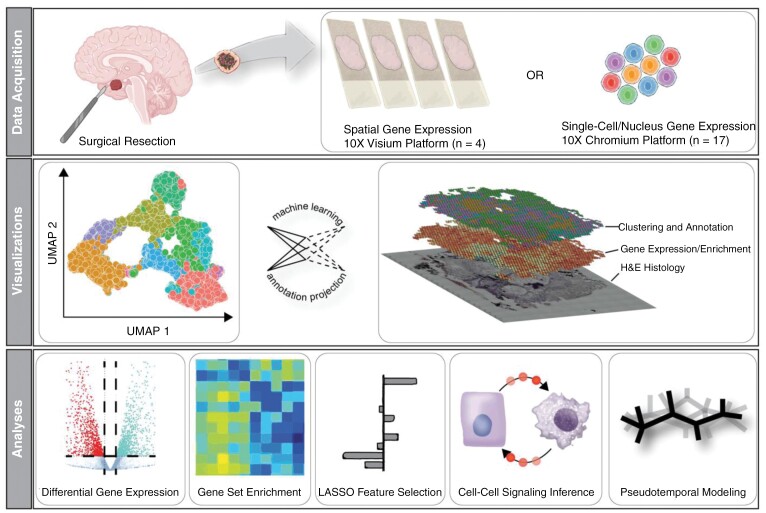

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

Key Points.

PI3K-mTOR active SASP cells are found in ACP epithelial, myeloid, and glial tissue.

Regulatory signaling loss in ACP epithelia boosts P53 and Akt expression, driving a SASP.

Importance of the Study.

Adamantinomatous craniopharyngioma (ACP) is a CNS tumor that significantly impacts one’s quality of life. Surgery and radiation are the only treatment options available for this condition. Recent studies have found that ACP tumors contain senescent epithelial cells that release SASP factors, which promote tumor progression and metastasis. Here, we computationally analyze and model single-nucleus, -cell, and spatial gene expression of ACP primary tumor tissue to investigate senescence and SASP in ACP tissue. We identified SASP(+) epithelial cells and myeloid and glial tissue, showing that they are colocalized in senescence micro-environments surrounded by macrophage and glial tissue. We further identified SASP(+) epithelial cells in ACP tissue associated with PI3K/Akt/mTOR activity and inferred to be driven by a loss of P53 regulatory signaling. This research shows that antitumor therapies, such as Akt/mTOR inhibitors, senescence-directed therapies, and immunotherapy utilizing checkpoint inhibitors, may be valuable additions to current regimens in clinical trials.

Cellular senescence is a non-proliferative state that has been linked to both oncogenesis and cancer suppression.1 Senescence associated secretory phenotype (SASP) is a term used to describe the release of several molecules from senescent cells.2 These molecules are released in response to various stresses and are believed to help the body respond to and repair damage. The SASP includes a variety of cytokines, chemokines, and other signaling molecules and is pro-tumorigenic in multiple systems.3 SASP contributes to tumorigenesis by promoting: (1) the growth and proliferation of tumor cells, (2) tumor angiogenesis, invasion, and metastasis, (3) cellular reprogramming and the emergence of tumor-initiating cells in culture, and (4) modulating the local immune response, thereby enabling immune evasion by senescent cells.4

Adamantinomatous craniopharyngioma (ACP) is the most common sellar/suprasellar tumor in children, accounting for 5–11% of all pediatric intracranial tumors, and is associated with a shortened lifespan and the lowest quality of life for any pediatric brain tumor. Mounting evidence suggests that non-proliferative senescent epithelial cells within ACP tumors contribute to tumor growth and invasion by secretion of SASP factors.5,6 Translation of these insights into biologically targeted therapies against ACP depends on further understanding the cellular phenotypes contributing to the SASP milieu.

Recent studies have identified several SASP-associated factors, including growth factors (e.g. members of the WNT, BMP, and FGF families and EGF), cytokines (eg, IL-6, IL-8, IL-1), chemokines, and metalloproteases at significant levels in ACP tumors.7 Furthermore, senescence and SASP markers are primarily localized within the β-catenin accumulating epithelial cell clusters.5,7 Previous single-cell technology studies have focused on hypothalamic invasion and immune compartment characterization.8,9 Using laser-capture microdissection (LCM) followed by RNA-seq helped identify characteristics of different cell compartments. However, morphological identification of cell groups may have been limited in identifying senescent cells within other tumor regions, such as palisading epithelial and glial reactive tissue.

This work uses single-cell, nuclei, and spatial gene expression technology combined with advanced statistical and machine learning methods (Graphical Abstract) to explore ACP tissue’s diverse gene expression patterns. Gene expression patterns linked to senescence and SASP are examined to investigate how mutant β-catenin and Wnt signaling may result in tumorigenesis. Additionally, we annotate and describe our data to provide an initial description of cellular networks within ACP tissue and to create a spatial model for this heterogeneous tumor.

Methods

Single-Cell, Single-Nuclei, and Spatial RNA Sequencing Acquisition and Processing

Cells for single-cell RNA sequencing were isolated from manually disaggregated tissue using papain enzymatic digestion (Worthington) and passed through a 50 µm filter. Viability was confirmed through Flow Assisted Cytometric Sorting performed by the University of Colorado Flow Cytometry Shared Resource. Cells for single-nuclei RNA sequencing were isolated from snap-frozen primary tissue samples and processed with a CHAPS-based buffer and an additional wash step to prevent cell-free RNA interference for single-nuclei and RNA sequencing. Bright-field microscopy determined the single nuclei yield, quality, and membrane integrity.10 Both scenarios utilized the 10× v3 sequencing platform (10× Genomics, USA). We measured spatial gene expression patterns within intact ACP tissue using the Visium platform (10× Genomics, USA). This platform integrates histological staining and imaging with next-generation sequencing, allowing an improved understanding of the spatial organization of 55-µm subregions of a histological specimen and their respective gene expression profiles. Processing and sequencing of Visium slides returned raw sequencing FASTQ files for analysis. The University of Colorado Genomics Shared Resource performed all genomic sequencing. Cell Ranger software (10× Genomics, USA) aligned and annotated raw sequencing reads to the GRCh38 reference genome. The resulting data were converted to a Seurat object, preprocessed, and normalized using the standard Seurat protocol.11 Batch effects were corrected using the Harmony algorithm.12

Gene Expression Clustering, Cell State Annotation, Enrichment Analyses, and Senescent Cell Inference

Seurat clusters cells based on similar gene programs using a graph constructed in PCA space with the Louvain algorithm to extract optimal clusters. These clusters represent groups of cells, nuclei, or spots that share a gene expression program, implying a distinct cellular state. The SignacX R package, which implements the Signac R algorithm utilizing the “cell state” key of Human Primary Cell Atlas (HPCA) as the annotation reference, is used to annotate cell, nuclei, and spot data.13,14 Based on our analyses and simplicity for the reader, we substitute the HPCA “Non-Immune” annotation as “glial tissue.”

Metascape and UCell were used for enrichment analysis to identify pathways promoting phenotypic changes in ACP cells.15 Metascape was used as a terminal analysis to organize and interpret differentially expressed genes identified between various subgroups of cells, nuclei, or spots. UCell was used to derive statistical relationships between subgroups of cells, nuclei, or spots and gene pathways or ontologies of interest.

We used UCell to analyze the enrichment patterns of gene lists identified by Apps et al.,7 which were obtained from RNA sequencing data acquired on samples isolated by laser-capture microdissection of ACP tissue. Specifically, we focused on the gene sets annotated as brown, blue, and magenta, corresponding to epithelial/mutant β-catenin, glial, and immune tissue. We decided to use these annotations for simplicity. Finally, the SenMayo enrichment score was calculated via UCell to identify SASP gene expression and allow for a detailed characterization of senescent cells.16 As suggested by the authors,16 SASP(+) cells are identified as those with SenMayo enrichment greater than the 90th percentile for that cell type.

Cytokine Signaling Inference and Pseudotemporal Modeling

Secretory signaling was inferred from gene expression data using standard methods provided by the CellChat algorithm with the CellChatDB reference dataset.17 Pseudotemporal ordering was performed on single cell and nuclei expression data using the monocle algorithm implemented in the monocle3 R package.18 The monocle3 implementation of the monocle algorithm requires the user to select the root cells representing the start of pseudotime. Root cells (n = 45) were identified as less than the 3rd percentile for SenMayo enrichment but greater than zero (ie, low SASP).

LASSO Feature Selection of Models

We employed the LASSO formula for feature selection and regularization to streamline our model. Our dataset contains more than 25,000 pathway terms, which can complicate interpretability and result in issues with multicollinearity and model overfitting. Using the LASSO algorithm, we identified a subset of pathway terms that significantly impacted the quantitative phenotype, such as senescence or pseudotime. We utilized the glmnet R package to create two separate models based on the same input (gene set enrichment matrix), one for predicting SenMayo enrichment and one for predicting pseudotime. We scaled the input matrix using base R’s “scale” function to ensure precise outcomes.

Distance Modeling

Tissue coordinates were extracted from Visium data using the GetTissueCoordinates function, and cluster assignments were mapped to coordinates by UID. A Euclidean distance matrix between Visium spots was generated using the dist function that is part of the base R environment. Redundant pairs were removed (eg, A–B = B–A), and UID pairs were labeled as adjacent or distant if they were in less than the 10th percentile or greater than the 90th percentile of all distances.

Computational Hardware and Software

All computational programs were performed on a 64-bit RedHat Enterprise Linux HPC running CentOS 7.4.1708. Analysis was conducted using custom R scripts supported by the tidyverse ecosystem.19

Immunostaining

Double immunofluorescence staining in human ACP paraffin sections was conducted according to previously described protocols.5 Primary antibody details and concentrations used were as follows: β-catenin (1:300, C7082, Sigma Aldrich), pDNA PKcs (1:200, ab18356, Abcam), PARP-1 (1:300, SC-8007, Santa Cruz), ɣH2A.X (1:400,613402, BioLegend). Finally, immunohistochemical staining of P53 (Novus Biologicals, Cat No. NBP2-00723) and p-Akt (Ser473; Cell Signaling Technology, Cat No. CST4060) was performed on primary resection samples submitted to the Histowiz service.

Results

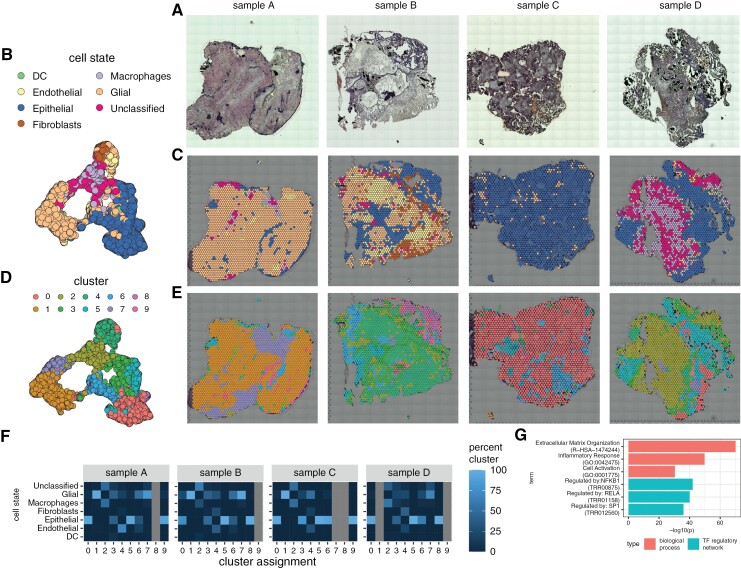

Spatial Gene Expression Heterogeneity in ACP Tumor Tissue’s Epithelial and Macrophage Compartments

We aim to unbiasedly identify epithelial, myeloid, and glial niches within ACP tissue by annotating cell states based on the HPCA. Cell states were determined to be Epithelial (n = 3323, 40%), Glial (n = 2880, 34%), Macrophages (n = 739, 9%), Endothelial (n = 376, 4%), Fibroblast (n = 260, 3%), Dendritic (n = 43, 1%), or Unclassified (n = 745, 9%; see Methods) (Figure 1a–c). We observed a high degree of heterogeneity across samples. Using clustering to identify the presence of subtypes within cell states, we observed glial and epithelial cells to possess the most significant number of cell state subtypes. This finding was consistent in all four samples (Figure 1f). Alternatively, macrophages and fibroblasts each demonstrated a homogeneous transcriptional cell state. Clustering alone, without cell state labeling, also revealed transcriptional heterogeneity. Specifically, 10 clusters were identified in the four samples (Figures 1c and 2d). As with the patterns of variability seen with analysis based on cell state, Seurat clustering also demonstrated variability within and between specimens. Based on Metascape, the most spatially variable genes were associated with transcriptional regulation by NFKB, RELA, and SP1 networks (Figure 1g). These signatures are not homogenous throughout the samples and exist in low and high NFKB, RELA, and SP1 network activation areas.

Figure 1.

Spatial transcriptional heterogeneity in adamantinomatous craniopharyngioma tissue. (a) Brightfield microscopy images for the four spatial gene expression samples acquired. (b, c). UMAP representation of spatial gene expression data annotated for inferred cell state with annotations overlayed on microscopy images. (d, e) UMAP representation of spatial gene expression data annotated for cluster ID with annotations overlayed on microscopy images. (f) Heatmap is stratifying the percentages of cluster cell state composition per patient. Note that all percentages are per column; a cluster typically corresponds to one cell type. (g) Enriched biological processes and transcription factor (TF) regulatory networks for spatially variable genes in ACP tissue.

Figure 2.

Gene set enrichment identifies epithelial (eg, tumor), glial, and immune spatial gene expression compartments within ACP tissue samples. (a) Example images of single-sample gene set enrichment analysis for Apps epithelial/CTNNB1 mutation, glial, and immune gene sets, respectively; red spots indicate high enrichment, and blue spots indicate low enrichment. (b) Scatterplot of enrichment scores for epithelial/CTNNB1 mutation and glial modules; spots are colored by cell state as shown in Figure 1b. (c) Enriched terms (ontologies, pathways, processes, diseases, cell types) for gene markers identified for top epithelial/CTNNB1 mutant (blue bars) and glial (red bars). (d) Boxplot of enrichment score distributions for tumor, immune, and glial signatures stratified by spatial gene expression sample.

Defining Spatial Gene Expression Patterns within Epithelial and Glial Compartments of ACP Tissue

To verify that the cell states identified represent cancer cells in ACP, we correlated the transcriptional signatures with previously published data from Apps, which utilized LCM and RNA-seq to identify compartments that included epithelial whorls, palisading epithelia, glial, and immune cells (Figure 2a).

Epithelial and glial cell components form distinct subgroups of spots (Figure 2b), supporting the assertion that ACP includes these separate tissue compartments. Our observations suggest that spots with the highest epithelial/CTNNB1 mutation content signature were distant from each other, resulting in sparse focal spots (Figure 2a [top row]). Conversely, spots with the highest glial content signatures were located closer to each other, forming denser continuous regions (Figure 2a [center row]). When mapped to the gene ontology (GO) knowledge graph, differentially expressed genes within epithelial cells correspond to Epidermis Development, Regulation of the Wnt Signaling Pathway, and Odontogenesis (Figure 2c). Differentially expressed genes within the glial compartment were associated with Gliogenesis, Childhood Astrocytoma, and Dorsal Root Ganglia cells (Figure 2c). Patient samples differ in their epithelial, glial, and immune cell composition (Figure 2d). Quantitative analysis confirmed that epithelial cells are found in concentrated spatial arrangements, mainly on a background of glial cells (P < .00001 (Supplementary Figure 1a–c).

Identifying Unique Cell Groups and Gene Expression Profiles in ACP Tissue

Our spatial gene expression data are precise to the 55 µm rather than the cellular level due to the limits of the technique and the cellular heterogeneity of ACP. To better understand heterogeneity at the cellular level, we use single-cell and single-nuclei gene expression analysis. At this level of resolution, we observed a greater variety of immune phenotypes than we did using spatial gene expression (Supplementary Figure 2a andb). The optimal number of distinct clusters increased from 10 to 23 (Supplementary Figure 2c). In the spatial gene expression data, Glial and Epithelial signatures exhibited the most diverse transcription patterns, while single cell/nuclei data demonstrated greater diversity among Immune and Glial cells (Supplementary Figure 2d–g). We mapped the 23 cluster IDs from the single cell and single nuclei dataset onto the spatial gene expression data through PCA space. We classified pairs of clusters as “adjacent” if within the 10th percentile of physical distance and “distant” if above the 90th percentile. Most pairs were in both groups, indicating that cell states are evenly distributed throughout ACP tissue and do not colocalize (Supplementary Figure 3). Within the spatial gene expression dataset, large regions of tissue display uniform gene expression patterns. There are also smaller areas within these regions that exhibit distinct gene expression signatures. These focal areas correspond to various compartments within ACP tissue, including immune, epithelial, and glial compartments (as shown in Supplementary Figure 3b and f). We specifically focused on the transcriptional profiles of Cluster 3 (epithelial) and Cluster 7 (fibroblasts), which were present in both adjacent and distant pairs. Our analysis revealed an overlap between spots labeled as Cluster 3 and those labeled as Cluster 7. Cluster 3 included many genes associated with the PI3K-Akt-mTOR signaling pathway (Supplementary Figure 3g).

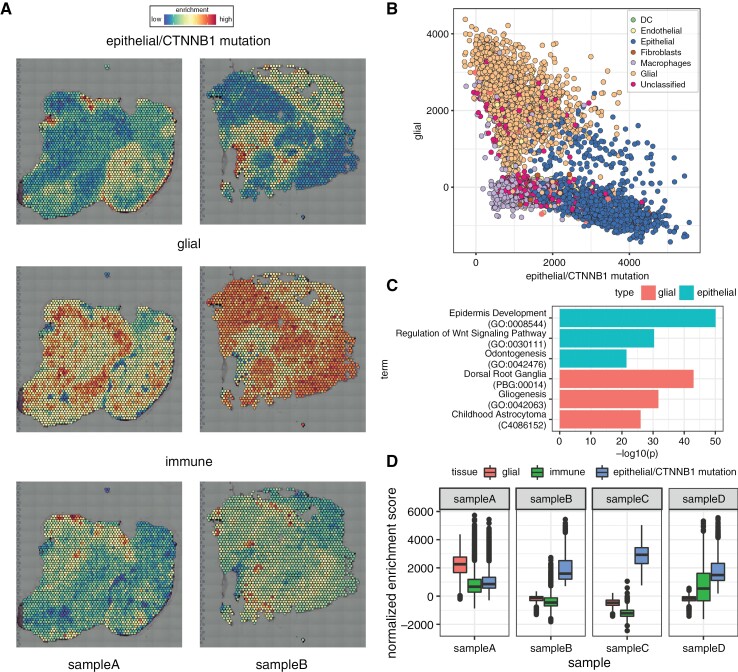

The Intricate Connection between Histological Morphology and SASP in ACP

It is established that ACP epithelial cells demonstrate four histological patterns: whorl-like (ie, cluster), palisading, stellate reticulum, and wet-keratin ghost cells. Senescent cells are believed to reside in the epithelial whorls. Using previously established gene expression thresholds,16 we examined the spatial gene expression data to identify senescent cells and those that exhibit a SASP. Interestingly, we identified SASP(+) regions within both palisading and whorl-like epithelial regions (see red arrows in Figure 3c). Immunostaining of ACP tissue showed β-catenin accumulating cells expressing senescence markers such as P21 and DNA damage response activation within both epithelial whorls and palisading epithelium (Supplementary Figures 4a–c).

Figure 3.

Transcriptional signature of SASP cells in ACP epithelial tissue. (a) Scatterplot of cells and nuclei according to normalized enrichment score of CellAge and GenAge gene sets. SASP cells are identified as those in the top 10% of enrichment for the SenMayo gene set. (b) SenMayo percentile versus NES for CellAge and GenAge gene sets; the dashed line indicates the 90th percentile. (c) Example of SASP spots in spatial gene expression dataset (sample A). Histological stain with arrows pointing to areas labeled as SASP positive. (d) Enrichment profiles for enriched genes identified in cells/nuclei with the top and bottom 10% SenMayo NES scores (eg, high/low SASP). (e) Boxplot of relative percentages for predicted cell cycle stage for cells/nuclei (bootstrap n = 1,000) stratified by SASP status. f. Genesets were identified as contributing to the SenMayo enrichment score through cross-validated LASSO regression (bootstrap n = 1,000).

Gene pathways associated with SASP(+) and SASP(–) cells were defined as SenMayo NES >90th or <10th percentile, respectively (Figure 3d). SASP(+) cells expressed markers for SASP and DNA Damage/Telomere Stress Induced Senescence, as well as Regulation of MAPK Cascade and Regulated by CTNNB1 signatures. (Note: Gene sets are listed hierarchically without indicating directionality. For example, we do not report if MAPK is upregulated or downregulated.). This aligns with the activation of WNT/β-catenin signaling and MAPK pathway in epithelial whorl cells.7 SASP(+) cells were also mainly in the G1/S cell cycle stage (Figure 3e), a hallmark of senescence.2

We hypothesized that SASP(+) epithelial signatures would be associated with Wnt/β-catenin signaling and EMT, which have been implicated in ACP pathogenesis, senescence, and SASP.20–23 We utilized the LASSO method to model senescence enrichment in ACP epithelial cells, determining the most associated transcriptional pathways based on MSigDB gene set enrichment scores. Analysis of epithelial cells identified no differentiation between whorls and palisading epithelia. The primary predictors of a SASP(+) signature were Targets of MYC, Normal Aging, and SHH pathway expression (Figure 3f). Importantly, Wnt and EMT candidate gene sets were not identified, suggesting that canonical Wnt signaling and EMT may not contribute to the development of SASP cells autonomously but through cell–cell communication.

Senescence Markers in ACP Tissue Beyond Epithelial Whorls

Through single-cell/nuclei RNA sequencing and spatial transcriptomics, sparsely distributed areas demonstrating a SASP(+) signature were identified outside epithelial whorls. Double immunostaining revealed P21 expression and DNA-damage response pathway activation, supporting this finding (Supplementary Figure 4a–d).

Single-cell, nuclei and spatial gene expression demonstrated macrophages to be most likely to present a SASP (+) signature (Figure 4 and b, Supplementary Figure 6). Relating this to the sc/sn-RNAseq data, 15% (23/154) of differentially upregulated genes in SASP(+) macrophages were regulated by the Sp1 transcription factor (TF) network. The Sp1 TF plays a role in cell growth, apoptosis, and immune responses and binds to GC-rich promoter regions for MAPK and Akt genes.24

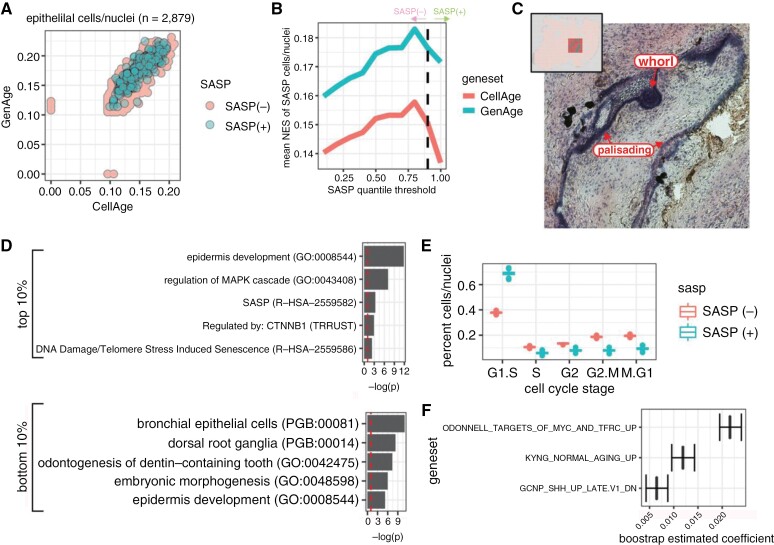

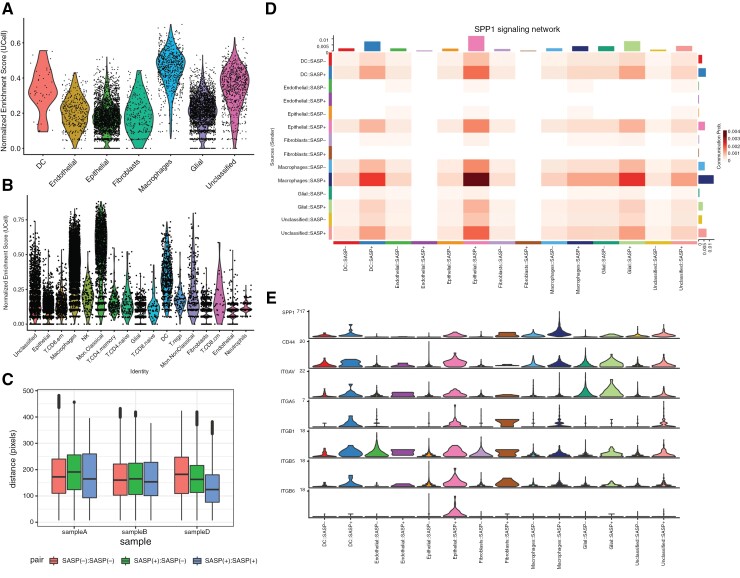

Figure 4.

Transcriptional SASP signatures are present in myeloid and glial compartments in ACP. Normalized enrichment score of SenMayo score across cell states in spatial (a) and single-cell/nuclei (b) gene expression data. (c) Distance (in pixels) between SASP(+) and SASP(–) spatial gene expression spots across patient samples. Note: sample C had no SASP(+) tissue detected and was omitted from this plot. (d) Heatmap displaying the likelihood of communication between two groups of cells for the SPP1 cytokine network. Rows present the sender of the ligand, and columns show the group to the receptor the ligand will bind to. (e) Violin plot of gene expression values for each annotated group for the ligands and receptors within the SPP1 network (as defined by CellChatDB).

SASP(+) glial cells had 16 differentially upregulated genes compared to SASP(–) glial cells, of which 38% (n = 6) are known to be transcriptionally regulated by RELA/NFKB1. SASP(+) glia and macrophages were enriched for neutrophil granulation and inflammatory transcriptional signatures, suggesting that these SASP(+) cell populations contribute to a proinflammatory micro-environment.

Additionally, SASP(+) cells tended to colocalize with other SASP(+) cells across all samples (Figure 4c, Supplementary Figure 5), suggesting that, even outside of epithelial whorls, SASP(+) regions comprised of epithelial, myeloid, and glial cells exist.

We applied CellChat analysis stratified by cell type and SASP status to identify secreted factors in ACP tissue. The most robust signaling network was Secreted Phosphoprotein 1 (SPP1; Supplementary Figure 7). This network comprises the secreted SPP1 ligand and the CD44 and Integrin receptors (ITGAV, ITGA5, ITGB1, ITGB5, and ITGB6; Figure 4d). SASP(+) macrophages were the most significant contributors to SPP1 secretion, and the CD44 and integrin receptors were present within SASP(+) epithelial cells as well as SASP(+) Dendritic Cells and Glia (Figure 4e). All SASP(+) cell types demonstrated more significant signals for incoming and outgoing cytokine messaging compared to SASP(–) cells (Supplementary Figure 8).

Cell–Cell Signaling Pathways Utilized Between Senescent and Non-senescent ACP Tissue

A hallmark characteristic of ACP is activated Wnt signaling. However, the precise role Wnt signaling plays in ACP pathogenesis has yet to be understood entirely. CellChat inferred that cell–cell signaling through the canonical Wnt pathway existed strictly between cells with epithelial and glial signatures (Figure 5a). In contrast, non-canonical Wnt signaling (ncWnt) existed not only between these cell types but also included SASP(–) macrophages (Figure 5b). When we isolated canonical Wnt signaling, we observed that the most robust pattern was between SASP(+) epithelial cells and SASP(+) glial cells, with weaker interactions from SASP(+) epithelial cells to SASP(–) epithelial and SASP(–) glial cells (Figure 5c).

Figure 5.

Inferred Wnt signaling patterns in ACP tissue. cell–cell communication patterns for (a) canonical and (b) non-canonical Wnt (ncWnt) signaling. (c) Canonical Wnt signaling pattern overlaid on histology image. (d) Heatmap with relative importance for canonical Wnt signaling network roles stratified by cell and SASP states. (e) Heatmap with relative importance for ncWnt signaling network roles stratified by cell and SASP states. Top contributing ligand–receptor pair communication patterns for (f) canonical and (g) ncWnt signaling.

A given cell type may play multiple roles within a paracrine signaling network. These may include sending, receiving, or modifying (ie, mediating or influencing) a signal. CellChat inferred that SASP(+) epithelia play a substantial role as sender, receiver, and modifier for canonical and ncWnt signaling networks (Figure 5d and e, respectively). Regarding canonical Wnt signaling, the most potent receiver is SASP(+) glial tissue, while ncWnt signaling targets include SASP(+) and SASP(–) glial tissue and SASP(–) epithelia. SASP(–) epithelia send signals only through the canonical Wnt pathway but function as receivers and modifiers in ncWnt signaling.

Wnt signaling networks include a variety of ligand–receptor (L–R) pairs, which include Wnt, Fzd, and Lrp family members. Previous studies identified that WNT5A and WNT6 ligands are more activated in the epithelial whorls than in palisading epithelia and reactive glial tissue.7 In our ACP specimens, WNT6 was particularly active as a ligand bound to the FZD6 + LRP6 receptor in canonical Wnt signaling (Figure 5f). The primary sender of WNT6 was SASP(+) epithelial cells, primarily bound to FZD6 + LRP6 on SASP(+) glia. SASP(+) epithelia also participated in a feedback loop using this L–R pair. In addition, SASP(–) epithelia sent WNT6 to SASP(+) epithelia and all glial tissue (SASP(+) and SASP(–)). An active L–R pair was WNT5A, acting as a ligand binding to FZD1 (Figure 5g). This signaling network’s primary senders and receivers were the SASP(+) epithelial and glial tissue regions.

Transcriptional Pathways Associated with Senescence Progression in ACP Epithelial Tissue

Pseudotemporal algorithms estimate a model of gene expression dynamics through the progression of biological processes, such as senescence.18 We created a pseudotemporal model of senescence within ACP epithelial cells and nuclei, in which cells displayed increasing senescence enrichment as the model advanced (Figure 6a). Positive trends in CellAge and GenAge gene sets indicated the model reflected the senescence process. The LASSO model for pseudotime, calculated from the MSigDB curated gene set library (n = 25,392 gene sets), identified transcriptional pathways associated with pseudotemporal progression. This determined positive contributions from Akt/mTOR, MYC, FZD, and Sonic Hedgehog pathways (Figure 6b). The most notable contribution to this model was a negative association with GLTSCR2, also known as NOP53. This gene regulates the binding activity of P53 and antagonizes Akt signaling. In agreement with previous reports,25–27 our results suggest that the loss of this P53 regulatory signaling network is associated with increased senescence. Supporting this finding, bulk RNA sequencing of a library of pediatric brain tumors and normal tissue controls demonstrated that ACP has uniquely high P53 activity (Figure 6c).

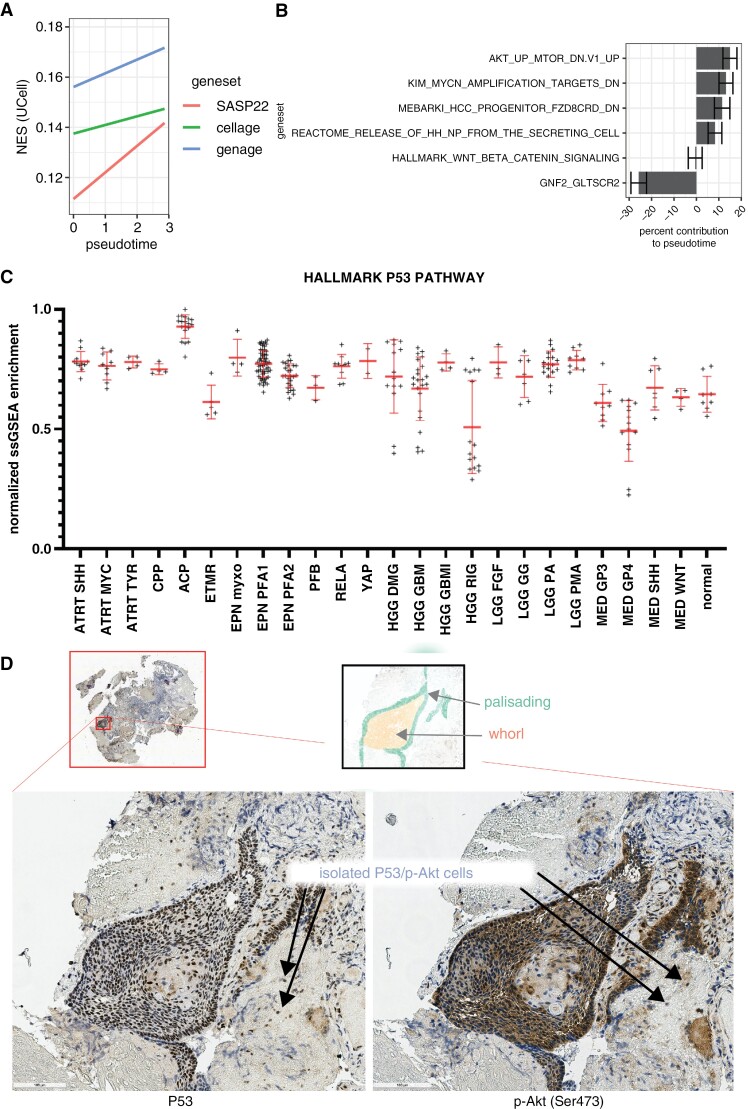

Figure 6.

Pseudotemporal model and bulk RNA-seq enrichment. (a) Linear models of SenMayo, CellAge, and GenAge normalized enrichment score (NES) on pseudotime. (b) Significant gene sets that help explain pseudotemporal development. (c) Normalized ssGSEA enrichment of MSigDB HALLMARK P53 Pathway across pediatric brain tumors. Immunostaining of P53 (d, left) and p-Akt (d, right) in ACP primary tumor tissue reveals P53 and p-Akt colocalization in densely packed clusters and sparse isolated cells.

Consistent with this, β-catenin accumulating cells outside the epithelial whorls and in the glial tissue showed markers of DNA damage (eg, PARP1 and pDNA-PKCs) (Supplementary Figure 4a–d). We also observed co-localized P53 activation (Figure 6d, left) and p-Akt activation (Figure 6d, right) in ACP tumor tissue. These findings indicate that during the development of senescence in ACP epithelial cells, there is a loss of anti-P53 regulatory signaling, leading to increased P53 and Akt expression in senescent cells, demonstrating a SASP.

Discussion

We conducted an unbiased analysis of spatial gene expression in ACP tumor tissue. Leveraging previous knowledge from laser-capture microdissected RNA-sequencing data, we identified unique cellular gene expression profiles within ACP and described spatial co-localization patterns. We examined a complex connection between histological morphology and SASP in ACP and observed senescence markers in ACP tissue beyond epithelial whorls. We further analyzed Cell–cell signaling pathways utilized between senescent and non-senescent ACP tissue and determined transcriptional pathways associated with senescence progression in ACP epithelial tissue. These findings provide valuable insights into the mechanisms driving ACP tumor development and progression and may inform the application of targeted treatments for this disease.

ACP affects children and adults and is quite complex from a histological standpoint. Even though new clinical trials have been launched, only some medical antitumor therapies are available. Developing safer and more effective treatments depends on an improved understanding of the biological processes critical to the development and growth of ACP. This study focused on the transcriptional characteristics of cell populations within ACP based on the knowledge that cell-to-cell communication is crucial to ACP pathogenesis. The study further demonstrates that ACP is transcriptionally and histologically heterogeneous across patient samples. Such tissue heterogeneity may affect tumor response to therapy. Therefore, It is essential to understand and target this heterogeneity to identify therapeutic vulnerabilities.

Our analysis of cell–cell signaling activity revealed SPP1 as the most potent secretory signaling pathway. This was especially true between SASP(+) epithelia and macrophages. Consistent with this finding, prostate cancer is characterized by SPP1 overexpression that is responsible for maintaining the activation of PI3K/AKT and ERK1/2 signaling pathways.28 Furthermore, activation of the MAPK/ERK pathway within tumor epithelium and glial reactive tissue in ACP is well established.7,29 This pathway has been implicated in driving the progression of SPP1-mediated EMT in prostate cancer.28 Our findings suggest that SASP(+) macrophages may promote the ACP epithelial tissue phenotype by secretion of SPP1 binding to epithelial CD44 or integrin complex receptors, activating the MAPK signaling cascade. Notably, in HNSCC, activation of the KRAS/MEK pathway contributed to the SPP1-induced malignant progression and resistance to cetuximab.30

We observed specific co-localized PI3K/AKT/mTOR patterns within our spatial gene expression data. There was an association between AKT/mTOR and senescence progression in ACP epithelial cells. Additionally, AKT and P53 were colocalized in ACP histological specimens. The PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway is pivotal in controlling cell survival, growth, proliferation, metabolism, and angiogenesis—all processes that, when dysregulated, contribute to cancer development and progression.31 Previous research has demonstrated that CXCL12 binding to CXCR4 triggers various signaling pathways, including PI3K/AKT/mTOR, which drive proliferation, migration, and invasion in ACP cell culture and patient recurrence.32,33 mTOR can activate senescent genes or gene programs.34 mTOR is a crucial protein that regulates several cellular processes like protein and lipid synthesis and autophagy.35 It is the chief switch controlling the cell’s catabolism and anabolism. It coordinates the cell’s response to different factors, such as nutrient availability, energy status, and growth factors.35 Various therapeutics that target PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling are clinically approved. Our data support growing evidence suggesting that targeting this signaling cascade could have therapeutic benefits for patients with ACP.

The study of senescence in cancer aims to understand the effects of inducing and removing senescent cells on tumor behavior.36 Our study found that ACP tissue contains areas with senescent signatures, surrounded by glial and myeloid cells that likely infiltrate into the epithelial tumor micro-environment. This supports previous studies suggesting that ACP tumor epithelia exist in a histological environment that includes reactive glia and immune cells.33 We used a single-cell and -nuclei gene expression dataset to confirm that senescent cells with an active SASP are present.5,7 Additionally, we demonstrated that immune cells play an active role in the SASP-like character of specific regions within ACP. Our spatial gene expression analysis identified SASP(+) epithelial cells in areas with both whorl-like and palisading morphologies, suggesting a dynamic range of SASP signatures within ACP tissue. Finally, our findings support the rationale for current clinical trials in ACP that employ MEK and pan-RAF inhibition, as we observed MAPK pathway activation in ACP tumor epithelial and glial reactive tissue.

Cell–cell signaling in ACP demonstrates activated Wnt signaling and has a senescent program that results in senescent cells exhibiting a SASP, especially in epithelial whorls. This suggests that the SASP is localized. Outside of the localized environment, communication occurs between non-senescent cells. The channels used for cell–cell communication vary depending on whether the cells are senescent. This suggests that interrupting specific ligand–receptor pairs in the cytokine signaling cascade could be a strategy that would be specific to SASP(+) cells.

The progression of senescence in ACP epithelial tissue is associated with P53 signaling. A core component of the DNA damage response is the P53 protein, which forms a complex with CDK2, causing cell cycle arrest and allowing the cell to repair the damage. Our model suggests that senescence in ACP progresses in only one direction, but studies have shown that pre-senescent or early senescent cells can reenter the cell cycle.37 Existing data indicate that senescence-associated DNA damage response signaling-related cascades, including NFKB, drive SASP genes in a mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR)-dependent manner.37 Additionally, NFKB plays a dynamic role in early senescent cells, leading to their activation and ECM remodeling, as well as becoming pro-inflammatory and pro-fibrogenic.37 When applied to the data from this report, these observations suggest potential therapeutic targets in ACP may be related to inflammatory response, cell activation, and extracellular matrix organization processes.

Finally, we need to be made aware of specific research that studies the relationship between cyst formation and senescence/SASP in ACP; evidence suggests that there may be a connection between them and that targeting the process may have therapeutic benefits. Senescent cells in ACP secrete inflammatory mediators, including interleukin (IL)1A and IL6 (a hallmark molecule of SASP, broadly). These and other inflammatory mediators, such as IL8, IL1B, MCP1, and CXCL12, have been identified within ACP tissues and cyst fluid, and the pattern of cytokines is suggestive of activation of the inflammasome. This innate immune effector mechanism results in a pro-inflammatory cascade. Tocilizumab, an IL6 inhibitor, has been found to cause a significant response in patients with cystic ACP. Therefore, there may be some association between SASP and cysts in ACP, but the specific functional relationship is unknown.

Limitations

Our data estimates the presence of mature spliced 3' mRNA and does not necessarily translate to functional aspects such as protein expression, conformation, modification, or altered epigenetic activity. Our spatial gene expression platform (ie, 10× Visium) has a resolution of 55 µm, which may include multiple cell types in a single spot, leading to potential loss of single-cell resolution and confounding data interpretation. Differences in tissue composition or intermixed cell types can complicate the mapping process. This heterogeneity may confound our mapping of cell-type specific signals to our spatial gene expression data. Although we have taken steps to provide multiple levels of evidence to support our annotations of these cell types, the assignment of phenotypes like SASP to specific cell types in our spatial gene expression data may still be compromised. Accordingly, there is a need to perform follow-up studies to validate our findings at the gene and protein level and through functional assays for concepts like EMT and immune response within ACP.

In addition, only a superficial acknowledgment of the inflammatory milieu is presented here. Further, there are several known transcriptional facets of ACP that we have not explored in this work, including TGF-β and BMP signaling, FGF signaling, pro-angiogenic VEGF signaling, and Hippo signaling.38 It is important to note that this work did not explain the precise role of Wnt signaling within the SASP(+) epithelial cell feedback loop shown in Figure 5f and g. While it is possible that Wnt signaling is initiated by SASP-like gene expression, it is similarly plausible that Wnt is self-perpetuating and contributes to the development of SASP-like gene expression. Future studies will be needed to describe better the specific contributions of Wnt5a and Wnt6 in promoting SASP in ACP epithelial cells.

Future Directions

Further granularity regarding the effects of senescence on ACP development will better guide potential therapies. Cells that undergo replicative senescence or are induced to senescence can exhibit stem cell properties, and adult tissue stems cell characteristics. Senescent cancer cells that escape by inactivating senescence-essential genes, such as the p53 regulatory network, have more significant potential for tumor initiation than cells that have never undergone senescence.37 Our senescent model indicated the presence of glia and odontogenic stem-like transcriptional signatures, which suggests the possibility of a specific odontogenic role for senescence in ACP epithelial tissue. Future work will investigate the implications of the failure of β-catenin protein degradation in senescent or SASP-expressing ACP cells.

Conclusion

In this study, we analyzed spatial gene expression in ACP tumor tissue and identified unique gene expression profiles and co-localization patterns. Senescence markers and transcriptional pathways associated with senescence progression in ACP epithelial tissue were found. Our results emphasize the importance of understanding ACP’s development and growth by studying the transcriptional characteristics of cell populations within ACP. Our research also highlights the importance of targeting the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway for ACP patients. SPP1 was inferred as a potent secretory signaling pathway in cell–cell signaling activity, promoting the ACP epithelial tissue phenotype. We suggest further investigation into the Interruption of specific ligand–receptor pairs in the cytokine signaling cascade as a strategy for targeting SASP(+) cells that communicate mainly with other senescent cells. Finally, we also discussed the progression of senescence in ACP epithelial tissue, which is associated with P53 signaling and DNA damage response. Potential therapeutic targets in ACP may be related to inflammatory response, cell activation, and extracellular matrix organization processes.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Eric W Prince, Department of Neurosurgery, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, Colorado, USA; Department of Biostatistics and Informatics, Colorado School of Public Health, Aurora, Colorado, USA; Morgan Adams Foundation for Pediatric Brain Tumor Research Program, Aurora, Colorado, USA.

John R Apps, Oncology Department, Birmingham Women’s and Children’s NHS Foundation Trust, Birmingham, UK.

John Jeang, Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s Cancer and Blood Disorders Center, Boston, Massachusetts, USA; Division of Pediatric Neurosurgery, Department of Neurosurgery, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, Alabama, USA.

Keanu Chee, Department of Neurosurgery, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, Colorado, USA; Morgan Adams Foundation for Pediatric Brain Tumor Research Program, Aurora, Colorado, USA.

Stephen Medlin, Department of Neurosurgery, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, Colorado, USA; Morgan Adams Foundation for Pediatric Brain Tumor Research Program, Aurora, Colorado, USA.

Eric M Jackson, Department of Neurosurgery, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

Roy Dudley, Department of Neurosurgery, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada.

David Limbrick, Department of Pediatrics, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri, USA; Department of Neurosurgery, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri, USA.

Robert Naftel, Department of Neurological Surgery, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Monroe Carell Jr. Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt, Nashville, Tennessee, USA.

James Johnston, Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s Cancer and Blood Disorders Center, Boston, Massachusetts, USA; Division of Pediatric Neurosurgery, Department of Neurosurgery, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, Alabama, USA.

Neil Feldstein, Department of Neurosurgery, Columbia University Medical Center, New York, New York, USA.

Laura M Prolo, Division of Pediatric Neurosurgery, Department of Neurosurgery, Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital, Stanford University School of Medicine, Palo Alto, California, USA.

Kevin Ginn, The Division of Pediatric Hematology and Oncology, Department of Pediatrics, Children’s Mercy Hospital, Kansas City, Missouri, USA.

Toba Niazi, Department of Pediatric Neurosurgery, Nicklaus Children’s Hospital, Miami, Florida, USA.

Amy Smith, Department of Pediatric Hematology‐Oncology, Arnold Palmer Hospital, Orlando, Florida, USA.

Lindsay Kilburn, Children’s National Health System, Center for Cancer and Blood Disorders, Washington, District of Columbia, USA; Children’s National Health System, Brain Tumor Institute, Washington, District of Columbia, USA.

Joshua Chern, Departments of Pediatrics and Neurosurgery, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia, USA; Department of Pediatric Neurosurgery, Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, Atlanta, Georgia, USA.

Jeffrey Leonard, Division of Pediatric Neurosurgery, Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus, Ohio, USA.

Sandi Lam, Division of Neurosurgery, Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois, USA.

David S Hersh, Division of Neurosurgery, Connecticut Children’s, Hartford, Connecticut, USA.

Jose Mario Gonzalez-Meljem, U. Tecnologico de Monterrey, School of Engineering and Sciences, Mexico City, Mexico.

Vladimir Amani, Morgan Adams Foundation for Pediatric Brain Tumor Research Program, Aurora, Colorado, USA.

Andrew M Donson, Morgan Adams Foundation for Pediatric Brain Tumor Research Program, Aurora, Colorado, USA.

Siddhartha S Mitra, Department of Neurosurgery, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, Colorado, USA; Morgan Adams Foundation for Pediatric Brain Tumor Research Program, Aurora, Colorado, USA.

Pratiti Bandopadhayay, Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s Cancer and Blood Disorders Center, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

Juan Pedro Martinez-Barbera, Developmental Biology and Cancer, Birth Defects Research Centre, GOS Institute of Child Health, University College London, London, UK.

Todd C Hankinson, Department of Neurosurgery, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, Colorado, USA.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Funding

This work was supported by The Brain Tumor Charity (UK) Grant Number GN-000522.

In addition, this work was supported by NIH/NCATS Colorado CTSA Grant Number TL1 TR002533. Contents are the authors’ sole responsibility and do not necessarily represent official NIH views. Finally, the authors thank the Morgan Adams Foundation for Pediatric Brain Tumor Research.

Authorship statement

E.W.P, J.R.A, J.M.B., and T.C.H. contributed to the conceptualization; E.W.P., V.A., and A.D. to the methodology; E.WP. and J.J. to the software; E.W.P. and J.J. to the formal analysis; E.W.P., J.J,. K.C., S.M., and J.M.G.M., to the investigation; E.M.J., R.D., D.L., R.N., J.J., N.F., L.M.P., K.G., T.N., A.S., L.K., J.C., J.L., S.L., and D.S.H., to the resources; E.W.P., J.J., K.C., and S.M., to the data curation; E.W.P, J.R.A., J.M.B., and T.C.H., to the writing—original draft; E.W.P., J.R.A., J.J., R.D,. D.L., R.N., J.J., N.F., L.M.P., K.G., T.N., A.S., L.K. J.C., J.L., S.L., D.S.H., J.M.G.M., V.A., A.D., S.S.M., P.B.M., J.M.B., and T.C.H., to the writing—review, and editing; E.W.P., J.R.A., J.M.B., and J.M.G.-M., to the visualization; J.R.A., S.S.M., J.M.B., and T.C.H., to the supervision; and E.W.P., J.M.B., and T.C.H., to the funding acquisition.

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

The study described in COMIRB protocol #95-500 was approved by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board and Colorado Ethics Committee. All participants were informed about the study’s purpose and any associated risks. Each participant signed a written consent form outlining the risks, benefits, and potential adverse consequences before collecting any primary tumor tissue samples or sequencing data. Participants were informed about their right to withdraw from the study at any time. All information collected during the study was kept confidential and only used for the study.

Data availability

The single-cell, -nucleus, and spaital sequencing data analyzed and the bioinformatic code used in this study are publicly available on GitHub (https://github.com/LeRicNet/ACP_NOD-23-00414).

References

- 1. Wang L, Lankhorst L, Bernards R.. Exploiting senescence for the treatment of cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2022;22(6):340–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kumari R, Jat P.. Mechanisms of cellular senescence: cell cycle arrest and senescence associated secretory phenotype. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9(1):485. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcell.2021.645593. Accessed April 25, 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gonzalez-Meljem JM, Martinez-Barbera JP.. Adamantinomatous craniopharyngioma as a model to understand paracrine and senescence-induced tumourigenesis. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2021;78(10):4521–4544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gonzalez-Meljem JM, Apps JR, Fraser HC, Martinez-Barbera JP.. Paracrine roles of cellular senescence in promoting tumourigenesis. Br J Cancer. 2018;118(10):1283–1288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gonzalez-Meljem JM, Haston S, Carreno G, et al. Stem cell senescence drives age-attenuated induction of pituitary tumours in mouse models of paediatric craniopharyngioma. Nat Commun. 2017;8(1):1819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Apps JR, Martinez-Barbera JP.. A promising future for hypothalamic dysfunction in craniopharyngioma. Neuro-Oncol. 2023;25(4):733–734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Apps JR, Carreno G, Gonzalez-Meljem JM, et al. Tumour compartment transcriptomics demonstrates the activation of inflammatory and odontogenic programmes in human adamantinomatous craniopharyngioma and identifies the MAPK/ERK pathway as a novel therapeutic target. Acta Neuropathol. 2018;135(5):757–777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jiang Y, Yang J, Liang R, et al. Single-cell RNA sequencing highlights intratumor heterogeneity and intercellular network featured in adamantinomatous craniopharyngioma. Sci Adv. 2023;9(15):eadc8933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wang C, Zhang H, Fan J, et al. Inhibition of integrated stress response protects against lipid-induced senescence in hypothalamic neural stem cells in adamantinomatous craniopharyngioma. Neuro-Oncol. 2023;25(4):720–732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Slyper M, Porter CBM, Ashenberg O, et al. A single-cell and single-nucleus RNA-Seq toolbox for fresh and frozen human tumors. Nat Med. 2020;26(5):792–802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Butler A, Hoffman P, Smibert P, Papalexi E, Satija R.. Integrating single-cell transcriptomic data across different conditions, technologies, and species. Nat Biotechnol. 2018;36(5):411–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Korsunsky I, Millard N, Fan J, et al. Fast, sensitive and accurate integration of single-cell data with Harmony. Nat Methods. 2019;16(12):1289–1296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chamberlain M, Hanamsagar R, Nestle FO, de Rinaldis E, Savova V.. Cell Type Classification and Discovery across Diseases, Technologies and Tissues Reveals Conserved Gene Signatures and Enables Standardized Single-Cell Readouts.; 2021:2021.02.01.429207. doi: 10.1101/2021.02.01.429207 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mabbott NA, Baillie JK, Brown H, Freeman TC, Hume DA.. An expression atlas of human primary cells: inference of gene function from coexpression networks. BMC Genomics. 2013;14(1):632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zhou Y, Zhou B, Pache L, et al. Metascape provides a biologist-oriented resource for the analysis of systems-level datasets. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):1523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Saul D, Kosinsky RL, Atkinson EJ, et al. A new gene set identifies senescent cells and predicts senescence-associated pathways across tissues. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):4827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jin S, Guerrero-Juarez CF, Zhang L, et al. Inference and analysis of cell–cell communication using CellChat. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):1088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Trapnell C, Cacchiarelli D, Grimsby J, et al. The dynamics and regulators of cell fate decisions are revealed by pseudotemporal ordering of single cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32(4):381–386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wickham H, Averick M, Bryan J, et al. Welcome to the Tidyverse. JOSS. 2019;4(43):1686. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Qi ST, Zhou J, Pan J, et al. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition and clinicopathological correlation in craniopharyngioma. Histopathology. 2012;61(4):711–725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Stache C, Hölsken A, Fahlbusch R, et al. Tight junction protein claudin-1 is differentially expressed in craniopharyngioma subtypes and indicates invasive tumor growth. Neuro Oncol. 2014;16(2):256–264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chen M, Zheng S, Liu Y, Shi J, Qi S.. Periostin activates pathways involved in epithelial–mesenchymal transition in adamantinomatous craniopharyngioma. J Neurol Sci. 2016;360(1):49–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Thiery JP. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in development and pathologies. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2003;15(6):740–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ivanenko KA, Prassolov VS, Khabusheva ER.. Transcription factor sp1 in the expression of genes encoding components of mapk, JAK/STAT, and PI3K/Akt signaling pathways. Mol Biol. 2022;56(5):756–769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Coppé JP, Patil CK, Rodier F, et al. Senescence-associated secretory phenotypes reveal cell-nonautonomous functions of oncogenic ras and the p53 tumor suppressor. PLoS Biol. 2008;6(12):2853–2868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sturmlechner I, Sine CC, Jeganathan KB, et al. Senescent cells limit p53 activity via multiple mechanisms to remain viable. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):3722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lujambio A, Akkari L, Simon J, et al. Non-cell-autonomous tumor suppression by p53. Cell. 2013;153(2):449–460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pang X, Zhang J, He X, et al. SPP1 promotes enzalutamide resistance and epithelial-mesenchymal-transition activation in castration-resistant prostate cancer via PI3K/AKT and ERK1/2 Pathways. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2021(1):5806602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Petralia F, Tignor N, Reva B, et al. ; Children’s Brain Tumor Network. Integrated proteogenomic characterization across major histological types of pediatric brain cancer. Cell. 2020;183(7):1962–1985.e31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Liu K, Hu H, Jiang H, et al. Upregulation of secreted phosphoprotein 1 affects malignant progression, prognosis, and resistance to cetuximab via the KRAS/MEK pathway in head and neck cancer. Mol Carcinog. 2020;59(10):1147–1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Karar J, Maity A.. PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in angiogenesis. Front Mol Neurosci. 2011;4(1):51. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnmol.2011.00051. Date accessed October 31, 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Yin X, Liu Z, Zhu P, et al. CXCL12/CXCR4 promotes proliferation, migration, and invasion of adamantinomatous craniopharyngiomas via PI3K/AKT signal pathway. J Cell Biochem. 2019;120(6):9724–9736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Apps JR, Muller HL, Hankinson TC, Yock TI, Martinez-Barbera JP.. Contemporary biological insights and clinical management of craniopharyngioma. Endocr Rev. 2022;44(3):bnac035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Herranz N, Gallage S, Mellone M, et al. mTOR regulates MAPKAPK2 translation to control the senescence-associated secretory phenotype. Nat Cell Biol. 2015;17(9):1205–1217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Laplante M, Sabatini DM.. mTOR signaling in growth control and disease. Cell. 2012;149(2):274–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Foulkes I, Sharpless NE.. Cancer grand challenges: embarking on a new era of discovery. Cancer Discovery. 2021;11(1):23–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lee S, Schmitt CA.. The dynamic nature of senescence in cancer. Nat Cell Biol. 2019;21(1):94–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Apps JR, Martinez-Barbera JP.. Chapter 4 - Pathophysiology and genetics in craniopharyngioma. In: Honegger J, Reincke M, Petersenn S, eds. Pituitary Tumors. Academic Press; 2021:53–66. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-819949-7.00020-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The single-cell, -nucleus, and spaital sequencing data analyzed and the bioinformatic code used in this study are publicly available on GitHub (https://github.com/LeRicNet/ACP_NOD-23-00414).