Abstract

Background:

The utilization of artificial intelligence and machine learning as diagnostic and predictive tools in perioperative medicine holds great promise. Indeed, many studies have been performed in recent years to explore the potential. The purpose of this systematic review is to assess the current state of machine learning in perioperative medicine, its utility in prediction of complications and prognostication, and limitations related to bias and validation.

Methods:

A multidisciplinary team of clinicians and engineers conducted a systematic review using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) protocol. Multiple databases were searched, including Scopus, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), the Cochrane Library, PubMed, Medline, Embase, and Web of Science. The systematic review focused on study design, type of machine learning model used, validation techniques applied, and reported model performance on prediction of complications and prognostication. This review further classified outcomes and machine learning applications using an ad hoc classification system. The Prediction model Risk Of Bias Assessment Tool (PROBAST) was used to assess risk of bias and applicability of the studies.

Results:

A total of 103 studies were identified. The models reported in the literature were primarily based on single-center validations (75%), with only 13% being externally validated across multiple centers. Most of the mortality models demonstrated a limited ability to discriminate and classify effectively. The PROBAST assessment indicated a high risk of systematic errors in predicted outcomes and artificial intelligence or machine learning applications.

Conclusions:

The findings indicate that the development of this field is still in its early stages. This systematic review indicates that application of machine learning in perioperative medicine is still at an early stage. While many studies suggest potential utility, several key challenges must be first overcome before their introduction into clinical practice.

This systematic review and meta-analysis identified 103 studies that employed artificial intelligence or machine learning to predict perioperative outcomes, but the overall quality was only modest with only 13% being externally validated. The authors conclude that the artificial intelligence and machine learning may hold great promise but are not ready for prime time.

Editor’s Perspective.

What We Already Know about This Topic

Artificial intelligence and machine learning may offer a novel approach to better predict perioperative outcomes.

What This Article Tells Us That Is New

This systematic review and meta-analysis identified 103 studies that employed artificial intelligence or machine learning to predict perioperative outcomes, but the overall quality was only modest with only 13% being externally validated. The authors conclude that the artificial intelligence and machine learning may hold great promise but are not ready for prime time.

Perioperative medicine is a multidisciplinary specialty that focuses on meeting the complex medical needs of patients at risk of complications from surgery. With the number of surgical operations worldwide expected to rise to 500 million by the end of the 21st century,1,2 there is a growing need to accurately identify patients at risk and to manage potential complications. The incidence of postoperative mortality ranges from 1.7 to 5.7%3–6 and accounts for 7.7% of the global burden of death.9 Postoperative morbidity represents a major issue, with 16% of patients developing serious complications.5,7,8 This can affect both quality and length of life, placing a significant burden on individuals, families, and the healthcare system.9–14

Over the last 10 yr, there has been an emergence of novel predictive tools for perioperative outcomes driven by artificial intelligence and machine learning techniques. These tools offer exciting opportunities for advancing perioperative medicine. However, effective implementation requires a comprehensive understanding of both their advantages and potential risks. Machine learning, a subset of artificial intelligence, relies on algorithms to make predictions or decisions without explicit programming. Machine learning can analyze large, intricate data sets, learn from the data, and improve its performance over time. By enabling more accurate risk prediction as well as personalized treatment plans, machine learning has the potential to enhance patient care and outcomes. Nonetheless, well founded concerns currently exist regarding bias, interpretability, and reproducibility.

The distinction between classical statistics and machine learning can be blurred as they share common techniques including the development of risk scores.15 Existing risk stratification tools such as POSSUM, SORT, and NELA have traditionally utilized logistic regression, a statistical technique also employed in machine learning for similar purposes.16 However, classical statistics may struggle with nonlinear relationships and large numbers of variables, whereas the advantage of machine learning lies in its diverse range of algorithms that can model complex relationships and perform variable selection.17

We herein report a systematic review that focuses on prognostic artificial intelligence and machine learning models in perioperative medicine, aiming to carefully appraise the literature and identify knowledge gaps. Bias was evaluated using the Prediction model Risk Of Bias Assessment Tool (PROBAST),18 and an ad hoc classification was developed to determine the readiness level of the machine learning algorithms reported. We narrowed the scope of this systematic review to include only those studies that explicitly utilized machine learning approaches. Risk stratification tools based solely on logistic regression, commonly used as clinical benchmarks, were not included. For an analysis of these scores, readers are directed to a separate review.16

Materials and Methods

This systematic review was structured according to the 2020 Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) protocols statement.19 The protocol was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (CRD42022345213).

A literature search was conducted using Scopus, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), the Cochrane Library, PubMed, Medline, Embase, and Web of Science and completed on August 8, 2023. A primary search strategy was developed creating strings of research including the following keywords: “artificial intelligence,” “machine learning,” “preoperative,” “perioperative,” “surgery,” “anesthesia.” The detailed research query is described in the appendix. Search results were imported into EndNote 20 (Clarivate, United Kingdom). To assess the eligibility of the studies we used the Transparent Reporting of a multivariable prediction model for Individual Prognosis Of Diagnosis (TRIPOD) checklist (fig. 1).20

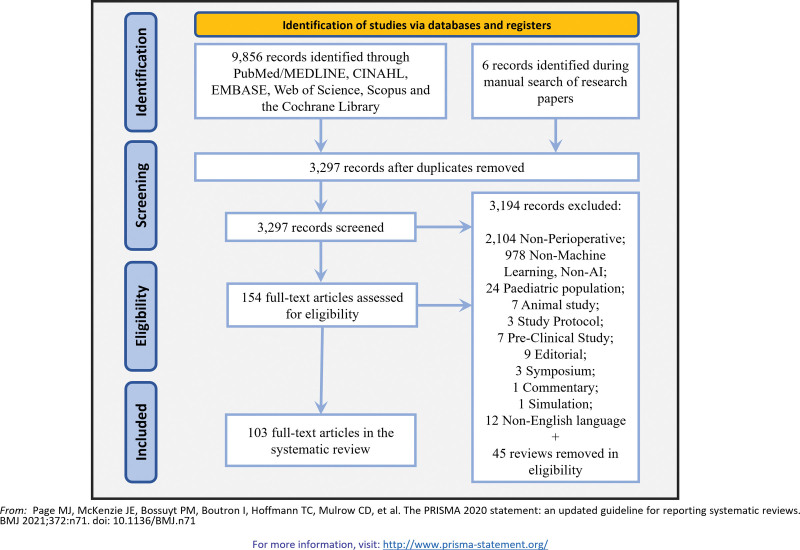

Fig. 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) 2020 flow diagram for new systematic reviews, including searches of databases and registries.

A multidisciplinary team of six reviewers assessed articles for eligibility, screening titles and abstracts to ensure relevance and identifying articles for full-text review. Each study was assessed by the reviewers independently. Two independent groups composed of two reviewers each (P.A., M.R.K. and D.A.H., W.P.) screened the full text to ensure each article was eligible following our inclusion and exclusion criteria. Conflicts were resolved by reviewer consensus.

We included retrospective and prospective studies in adult patients (18 yr old or older) published in the English language between January 1, 2000, and August 8, 2023. Outcomes of interest comprised but were not limited to:

-

Mortality

Perioperative mortality risk

-

Morbidity

-

Anesthesia risk

Risk of difficult/failed intubation

Need for massive transfusion

-

Intraoperative complications

Bradycardia

Hypotension

Other potential complications

-

Postoperative complications

Sepsis

Respiratory failure

Cardiovascular failure

Renal failure

Ileus

Soft tissue, skin, or wound infections

Delirium

Pain

-

-

Process

Need for intensive care unit admission

Length of hospital stay

Overnight hospital stay

Readmission to hospital

Exclusion criteria included pediatric populations, non-English language articles, protocol studies, symposium papers, studies conducted on animal models, in vitro studies, non–perioperative-focused studies, and studies unrelated to machine learning or artificial intelligence.

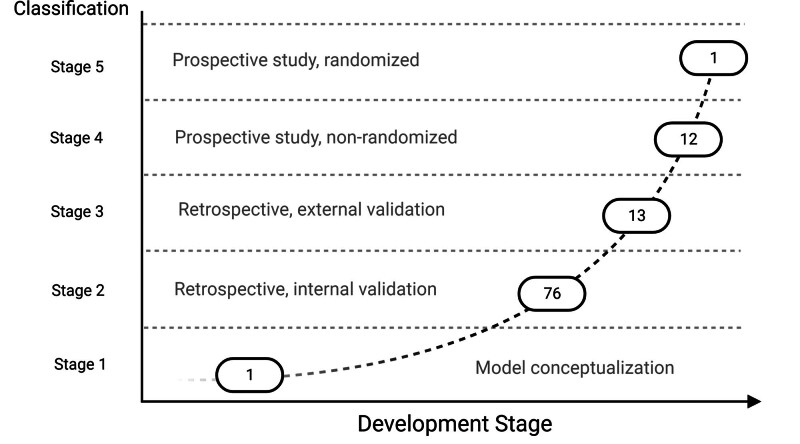

Study quality was assessed using established methodologies. To assess study quality and the readiness level of the machine learning algorithms, the authors created agreed ad hoc criteria (table 1; supplementary table 1, https://links.lww.com/ALN/D308). This is the recommended approach to assessing heterogenous nonrandomized clinical trials.21 The grading describes the readiness level of each machine learning model for possible clinical application, the type of study conducted, and the degree of validation.

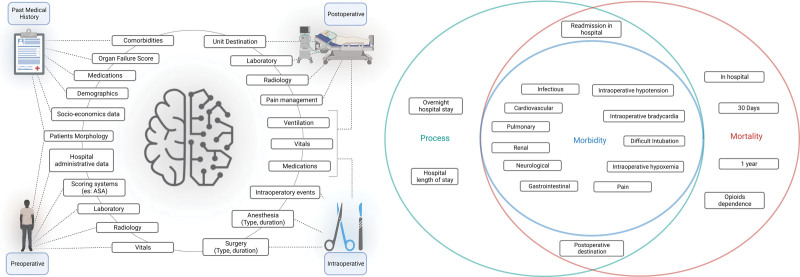

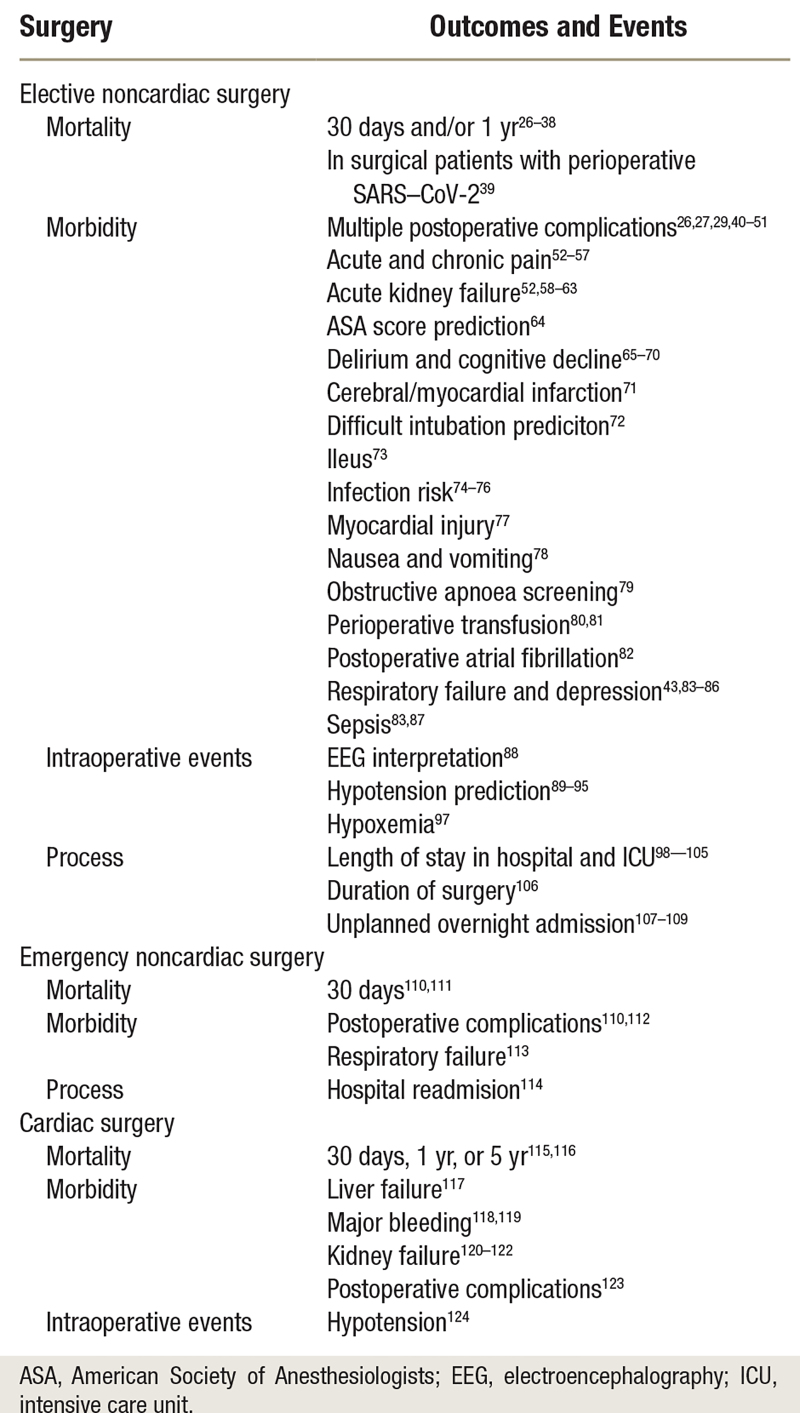

Table 1.

Ad Hoc Author Classification to Describe the Development Stage toward Clinical Application of the Models Described in the Studies

Five authors (P.A., M.R.K., D.A.H., W.P., and P.R.) independently assessed the quality of studies that met the inclusion criteria using the PROBAST to review all prognostic artificial intelligence and machine learning models developed or validated in perioperative medicine (fig. 2 and fig. 3). Cohen’s κ agreement between authors was calculated.22 This tool evaluates the risk of bias in studies across four domains: participants, predictors, outcome, and analytic technique. The applicability of each study to the search question was assessed by evaluating its relevance to the specified population, predictors and outcomes.18,23 A score was assigned to each study based on this tool.24 A PROBAST is being specifically developed to assess artificial intelligence and machine learning models (PROBAST–artificial intelligence)25 but was not available at the time of study.

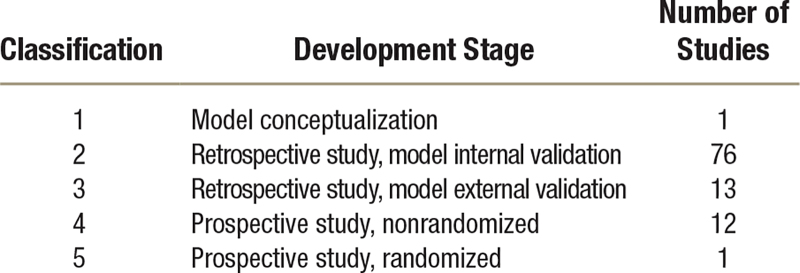

Fig. 2.

(Left) Graphical description representing the four feature categories used in perioperative medicine. (Right) Venn diagram of outcomes predicted in perioperative medicine. Green, process-related outcomes; blue, morbidity-related outcomes; red, mortality-related outcomes. ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists.

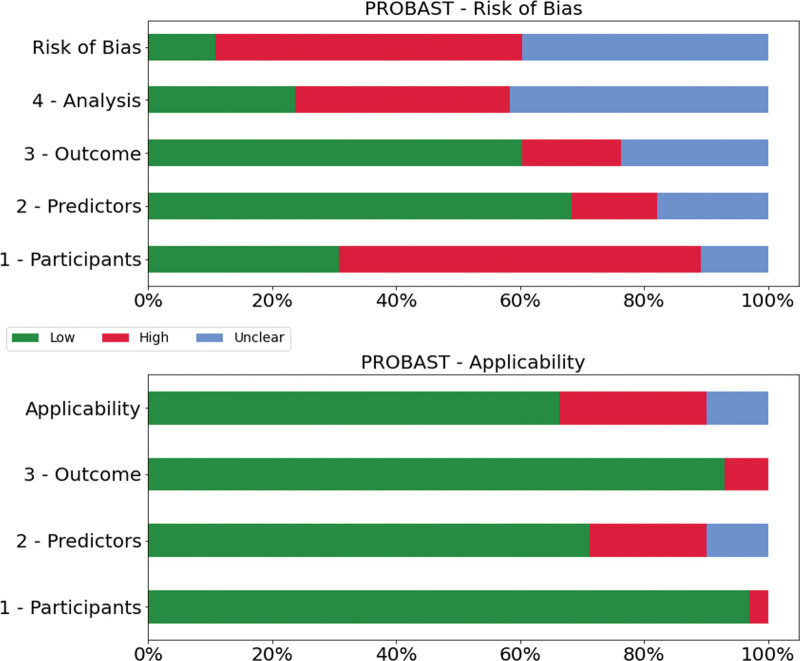

Fig. 3.

Prediction model Risk Of Bias ASsessment Tool (PROBAST) assessment.

The data were extracted into tables by the two groups of two reviewers and cross-referenced to identify possible errors. Variables were extracted and tabulated in Excel (Office 365, Microsoft, USA), summarizing study content and using standard terminology (supplementary table 1, https://links.lww.com/ALN/D308). The best area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) and metrics available for each described model were recorded. The AUC values were included as part of our study reporting and analysis rather than for the purpose of comparing performance between different studies or models. The values were expressed as mean or median, as appropriate. Summary data were used to produce the figures and tables describing the different studies.

Results

Study Selection

An initial search identified 9,856 articles that satisfied our criteria (fig. 1). After removal of duplicates, 3,297 articles were retained; of these, 154 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility, of which 103 studies met the inclusion criteria. These studies are summarized in table 2 and supplementary table 1 (https://links.lww.com/ALN/D308), including study design, patient populations, outcomes (or target variables), machine learning models applied, model performance and validations, and study limitations. Most of the studies were published in 2021 or 2022. Studies predominantly originated from the United States (48), the People’s Republic of China (22), and South Korea (12).

Table 2.

Summary of Outcomes and Events in Elective, Emergency, and Cardiac Surgeries

Study Types

A total of 63 studies were retrospective single-center: 13 were retrospective multicenter, and 11 employed retrospective analyses of national databases. Only 10 studies were prospective single-center, and 2 were prospective multicenter.40 One study utilized both a retrospective database and enrolled patients for a prospective study,89 while another used a cross-sectional study design.58 Two studies were secondary analyses of previous research, and one article described a specific model.41 There were 85 internal databases used to develop and evaluate the different models. External validation was performed in 12 studies.42,74,78,125 As reported in supplementary table 1 (https://links.lww.com/ALN/D308), most studies utilized tabular data, whereas those that predicted real-time events employed time-series analysis. A single study employed an image database.72

Risk of Bias Assessment with the PROBAST

The results are summarized in supplementary table 2 (https://links.lww.com/ALN/D309) and figure 3. Cohen’s κ agreement among authors averaged 0.71, indicating substantial agreement. Most studies described the development of prognostic models. Of all the articles, 90% were rated as having a high or uncertain risk of bias. The predominant reasons for the high or unclear risk of bias in the analysis domain were the lack of timely and accurate description of model metrics, insufficient or unclear number of events per predictor included in the model, and/or unclear assessment of overfitting correction and adaptation. In the participant domain, patient selection was often not clearly stated, nor was there a clear description of inclusion and exclusion criteria, leading to a high risk of bias in 75% of studies. The overall risk of bias was high, as almost 90% of the articles did not present external validation. With respect to applicability, the predictor domain had the highest level of possible bias. Several studies used particular features such as insurance codes to identify procedures or utilized medical intraoperative data such as continuous electroencephalography (EEG) monitoring that are not routinely collected and may not be broadly available.

Machine Learning Model Development Stage

Using our ad hoc classification (table 1 and fig. 4) to assess study quality and to quantify the development and implementation of machine learning models in perioperative medicine (supplementary table 2, https://links.lww.com/ALN/D309; figure 4), one study (1%) was classified as stage 1 or pre–model conceptualization;41 76 (74%) were classified as stage 2 or model developed using a retrospective data set with internal validation; 13 (13%) were classified as stage 3, or models developed using retrospective study but with external validation;58,78,125 and 12 (11%) as stage 4, a model trained over prospective studies with internal validation. Only one (1%) study achieved a stage 5 grading. This was a prospective study with randomized control trial characteristics; however, it was conducted unblinded and limited to only 68 patients.90

Fig. 4.

Graphical representation of the number of articles divided by the clinical development stage according to our ad hoc classification method.

Model Validation Methods

All studies performed internal validation (supplementary table 1, https://links.lww.com/ALN/D308), albeit using different approaches. A total of 10 studies did not state the method of validation, while 36 performed multiple-fold cross-validation. The remainder used a hold-out method, typically using a training:test ratio of 70%:30% or 80%:20%. External validation utilizes databases that are completely independent from the one used to create the model. However, only 14 (13%) studies applied external validation,26,27,42,52,58,74,78,80,83,98,112,114,126 while the remaining 87% used only internal validation.

Machine Learning Algorithms

Most studies reported their model performance using standardized classification metrics, namely sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, Brier score, area under precision recall, and F1 score.127 All models reported AUC (or C-statistic), a measure of the ability of a classifier to distinguish between two classes.128 For regression, the metrics reported were mean squared error and mean absolute error. Supplementary table 1 (https://links.lww.com/ALN/D308) shows all evaluation metrics of the models and the best performing model reported for each study.

Outcomes

There was a high level of heterogeneity in the application of artificial intelligence and machine learning to perioperative medicine, as shown by the wide range of outcomes studied. The main outcomes are categorized by type of surgery (table 2). The type of outcome and features used are shown in figure 2, and the details of the machine learning models are reported in supplementary table 1 (https://links.lww.com/ALN/D308).

Morbidity

Morbidity outcomes include deviations from normal patient trajectories in the postoperative period, e.g., development of kidney failure or delirium. Given the substantial volume of studies in this area, the outcomes were further categorized based on the typology of the potential clinical tool and the type of data used:

Prognostication models: designed to predict the risk of adverse events, complications, or other negative outcomes in patients, based on tabular data.

Real-time prediction models: designed to aid clinicians in making decisions during surgery or other medical interventions during clinical operations, usually based on time-series data.

There were 89 studies describing different types of morbidities. Fuller details of model performances are shown in supplementary table 1 (https://links.lww.com/ALN/D308).

Prognostication Models.

These studies created models to stratify patients into different risk levels during the perioperative period using tabular data exported by electronic health record systems or obtained from national databases such as the American College of Surgeons–National Surgical Quality Improvement Program database.129 The main features used to run these models were demographic and socioeconomic data, diagnosis, medical history, scores such as American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) status or Charlson Comorbidity index, type of anesthesia, type of surgery, duration of surgery, training level of the surgeon, and clamp time.130

Anesthetic and surgical risks: Several models were developed to predict anesthetic risk,64 risk of postinduction hypotension,124 identifying patients at risk of obstructive sleep apnea,79 or risk of postoperative re-intubation.43,84 Tavolara et al.72 used an online database comprising thousands of celebrity faces to train a neural network model to predict the risk of difficult intubation using a standardized picture of the patient.

Development of postoperative complications: Most studies focused on the prediction of postoperative acute complications26–28,42,44–49,59,99,110,112,113,118,123 such as pain and opioid use,53–57 postoperative atrial fibrillation (new-onset atrial fibrillation),82 postoperative risk of stroke or myocardial infarction,50,71,77 and delirium or cognitive decline.65–70 Other models focused on the risk of developing pneumonia or respiratory failure,83,85,125 acute kidney injury,43,52,58,60–63,120–122 liver failure117 or development of sepsis or surgical site infection.74–76,87,99,131 Suhre et al.78 analyzed the association between perioperative nausea and vomiting and cannabis use using a long-term survey.

Transfusion need and blood pressure prediction: Three studies developed models to predict the risk of perioperative transfusion in general surgery80,81 and cardiac surgery.119 Tan et al.51 developed a model to predict early phase postoperative hypertension after carotid endarterectomy. Hatib et al.89 used preprocessed data from continuous arterial monitoring obtained during surgery to assess the risk of intraoperative hypotension.71,78

Noteworthy studies: Bihorac et al.29 and Feng et al.41 created MysurgicalRisk, an ensemble model integrated with their hospital electronic health record system. This system, using more than 285 features, performed well and currently represents the best example of dynamic integration of different types of features such as clinical and socioeconomic data. The system was modeled around a specific electronic health record system and could potentially be adapted to other electronic health records. The second, from Xie et al.,73 used blood metabolomic profiling to predict the risk of postoperative gastrointestinal failure.

Real-time Predictive Models.

This category of studies encompasses models specifically designed to predict acute perioperative events in real time, delivering timely alerts to clinicians either during surgery or in the immediate postoperative period with the goal of promptly addressing or even preventing the issue.

Intraoperative monitoring: Other than one study focusing on prediction of bradycardia, the remainder utilized time-series analysis of intraoperative data to enable real-time trending of vital signs. Intraoperative depth of anesthesia using real-time EEG data,88 acute events such as intraoperative hypotension,90–94,132,133 postoperative hypertension,51 bradycardia,95 hypoxemia97 and blood product use during caesarean section81 were modeled. As an example, Cartailler et al.88 analyzed continuous EEG readings using a model that recognized abnormal wave patterns to identify suppression bursts.89

Postoperative complications: Two studies analyzed time-series data from wearable devices after surgery to anticipate complications in high-risk patients40 or respiratory failure in patients receiving opioids.86

Mortality

Twenty-one studies developed models for prognostic stratification of high-risk patients. Mortality outcomes included models predicting any death, regardless of cause, occurring within a fixed time period after surgery, either inside or outside hospital (usually 30 days or 1 yr), divided by the type of surgery.

Major elective surgery: Mortality was assessed postoperatively27–36,100 in the surgical intensive care unit35 or in the hospital.28,29,32,36,100 One study predicted 30-day mortality risk related to myocardial injury in noncardiac surgery patients,37 while another developed a natural language processing model using deep learning to analyze medical records and obtain diagnoses directly from notes written by a physician.27–35,38,100

Mortality in surgical COVID-19 patients: The COVIDSurg collaborative international panel conducted an international prospective study to develop and validate models that predict postoperative mortality risk in patients with perioperative SARS–CoV-2 infection.39

Mortality in perioperative medicine is defined as a rare event (probability less than 5%). Consequently, databases used for mortality may exhibit severe outcome imbalances. Of the 21 studies predicting mortality, 19 were missing other metrics or reported either low sensitivity or low precision. These models had a low F1 score (a measure of model accuracy), indicating a high number of false positives. Using a Random Forest model, Yun et al.35 did report clinically useful results with an F1 score of 0.84 and sensitivity of 0.90. Castela Forte et al.115 developed a Super Learner Algorithm (Ensemble model) to predict 5-yr mortality after cardiac surgery, reaching the following values: AUC of 0.81, specificity of 0.70, and sensitivity of 0.69.

Process

Process outcomes models relate to logistical aspects such as postoperative destination and length of stay. These models are usually linked with other types of outcome such as mortality. Thirteen articles focused on predicting nonclinical outcomes, all using models that stratified high-risk patients.

Unplanned hospital stay: Most studies predicted unplanned hospital stays after ambulatory or day surgery,101,107–109 such as an unplanned overnight stay in the hospital.107–109

Need for intensive care unit stay for more than 24 h99,100,102–104

Readmission and discharge timing: Several studies predicted the risk of hospital readmission within 30 days of surgery,114 when patients would be ready for hospital discharge98,102 or length of stay after orthopedic surgery.99,103–105

Surgical duration prediction: Gabriel et al.106 developed a XGB regressor to predict case duration in spinal surgery. These studies used tabular data containing previously mentioned features, with the addition of frailty scores.

Benchmarks

Forty-four articles used different strategies as comparators of their machine learning model performance (supplementary table 1, https://links.lww.com/ALN/D308). Three main types of benchmarks were identified, comparing models against results obtained from:

Multivariate logistic regression30,31,36,43,48,54,55,60,62,65,67,69,75,76,78,80,95,106,107,110

Previously validated scores such as perioperative medicine-related scores (e.g., ASA status, POSSUM, Charlson Comorbidity Index, or National Surgical Quality Improvement Program calculator scores)30,32,49,61,100,104 or other scores58,62 (e.g., Bariclot tool, STOP-BANG score, Mallampati test, various frailty indexes, and the acute kidney injury score)34,49,58,72,79,82,86,114,121

Overall, the machine learning models described in these articles outperformed their technical or clinical comparator, with an average increase in AUC and accuracy between 0.2-0.3, except for that of Chen et al.38 where the ASA score alone, despite a lower AUC, had higher accuracy compared to neural network and logistic regression models.

Discussion

This systematic review demonstrates the current breadth of applications of artificial intelligence and machine learning models in perioperative medicine for both prediction of perioperative complications and prognostication. Most approaches remain in the early stages of development but are generating promising preliminary results. The substantial increase in machine learning research for perioperative medicine applications is evidenced by the more than 100 articles published in the past decade, incorporating several million patients, with over two-thirds appearing in the last 2 yr. The United States and China, the leading countries in artificial intelligence development, contributed the highest number of publications, followed by South Korea. These findings are consistent with the current use of artificial intelligence in other medical fields such as radiology. We would expect applications to continue to grow rapidly in step with nonmedical usage.134,135

Our primary finding, derived from the PROBAST assessment (fig. 3), was that a large proportion of published studies exhibit a high or unclear risk of bias. This suggests that the study design or execution may lead to misleading results. Indeed, most studies were based on retrospective data and used only internal validation. Most studies also presented some form of bias in their selection criteria of the population or the structure of data extraction. This may significantly affect the broader validation of the models generated by these studies. Bias in population selection can arise from a variety of factors such as inadequate representation of diverse patient groups, variations in disease prevalence or treatment methods across different geographical regions, and limitations in data availability. Similarly, issues with the structure of data extraction can result in incomplete or inconsistent data sets, which can, in turn, affect the accuracy and reliability of the models generated.

Some studies, particularly those examining mortality, only reported partial metrics for their models. This lack of comprehensive reporting can lead to overestimated performance metrics and excessive faith in the model’s predictions. Another significant source of bias in the analyzed articles stems from an absence of detailed descriptions regarding calibration. This omission hampers the ability to assess the clinical value of the models, as calibration is essential in determining how accurately the predicted probabilities align with observed outcomes. Together, these factors affect the models’ relevance and reliability in a clinical setting. Our analysis highlights important areas for improvement in future research.

Our second major finding, from the ad hoc classification, was the heavy reliance on internal validation that was primarily conducted using limited data sets obtained from single centers. Most studies lacked external validation; this was a significant contributor to the high risk of bias identified. Studies with the lowest risk of bias were those that utilized data collected from multicenter studies or were derived from national databases.105 In terms of confirming generalizability and clinical implementation of machine learning models, external validation should be mandatory, ideally performed in different hospitals,136 and using separate cohorts of patients to evaluate model performance.136 The sharp trajectory of machine learning publications relates to the increasing availability of electronic medical data sets that can be interrogated for patterns and outcomes. Machine learning techniques hold great potential in extracting valuable insights from medical data and aiding decision-making. However, machine learning models trained on such limited data may not adequately capture the heterogeneity and complexity of real-world scenarios. Robustness needs to be confirmed before their widespread adoption, especially as models are generated from data that are not necessarily collected in other institutions. Populations may also differ in crucial respects.

Third, we identified challenges with models predicting perioperative mortality. Mortality rates are now low in elective surgery. Data sets are thus highly imbalanced and can skew predictive models toward exhibiting high false-positive rates. There are several implications arising from such performance issues, as the overestimation of mortality risk could lead to an unnecessary psychologic burden on the patient and a management dilemma for clinicians. Exploring different types of features, such as physiologic variables derived from preoperative tests such as cardiopulmonary exercise testing, or adopting classical approaches may hold the key to improving the accuracy and reliability of mortality prediction models in perioperative medicine. Recent work has suggested that instead of providing incremental value for predicting uncommon outcomes in large data sets, machine learning methods generally do not outperform classical statistical learning methods, which have been found to perform well in low-dimensional settings with large data sets.137

These findings demonstrate that use of artificial intelligence and machine learning in perioperative medicine is still in the early stages of development compared to other specialties such as radiology and ophthalmology, e.g., for cancer screening and retinopathy.138,139 Whereas the use of machine learning in these specialties are primarily used as diagnostic aids, its use in perioperative medicine encompasses a broad range of applications including prognostication, analyzing vital signs for clinical decision support, and predicting complications. The analytical tools and technologies developed for radiology image processing and analysis are generally more robust, well established, and validated. The size, breadth, and quality of large databases in perioperative medicine are limited but improving, and confirmatory external validation is largely lacking. Validated and generalizable machine learning models will provide perioperative medicine clinicians with valuable insights including a wealth of data for inferential research and assistance in decision-making, both for clinical management support and for identifying the appropriate level of postoperative care.

A noticeable trend is the emergence of machine learning models integrated into the hospital electronic healthcare record system such as that described by Bihorac et al.29 These systems utilize machine learning algorithms and deep learning models to analyze patient data throughout their hospital stay, essentially tracking their clinical journey. The goals are to provide clinicians with objective contemporaneous data to support clinical decisions and to empower patients to make informed decisions. Although promising, their widespread clinical implementation is still distant. Development and deployment of real-time decision support system models are outside the scope of this review but also hold great potential if outcome benefits can be formally and prospectively demonstrated through earlier recognition of deterioration and/or guided management. For example, it is still unclear whether interventions that reduce the incidence and duration of intraoperative hypotension will ultimately improve patient outcomes.140

Recommendations

While artificial intelligence and machine learning hold great potential in revolutionizing perioperative medicine and improving outcomes, current limitations must be first addressed, such as the issues addressed above regarding bias, external validation, generalizability, and achieving model stability. Other reviews on medical applications of artificial intelligence and machine learning provide more detailed insights.141–146

Progress has been made in understanding the limitations of human cognition, but significant gaps still remain.147 We therefore recommend adopting a human-centered design approach in conjunction with a continuous artificial intelligence development cycle with the aim of enhancing clinician performance.

To enhance the quality of databases and, subsequently, the models from which they are derived, we propose a multimodal approach that integrates diverse data from various sources, e.g., physiologic, biochemical, genetic, and imaging. Many machine learning models are data hungry; to avoid overfitting, integration of diverse data can be a key strategy in developing more robust and reliable models.148 The creation and integration of machine learning models into electronic healthcare records can address biases and limitations. However, careful design and quality control are necessary to ensure data utility beyond billing or workflow measurement.

Study Limitations

It was not possible to objectively assess the data sets of the publications, so we relied upon limitations reported by the authors. Our insights into limitations are also limited by the quality and completeness of the articles. It was not possible to access underlying code or data sets in most publications assessed, nor was it possible to assess validation methods. Last, despite conducting a thorough systematic review, some articles may have been inadvertently overlooked. Nonetheless, the consistency and strength of our findings demonstrate that the trends we have identified are likely to be reflected elsewhere.

Conclusions and Future Prospectives

The growing complexity and volume of data in perioperative medicine underscore the theoretical potential of artificial intelligence and machine learning in this field. Possible applications could range from risk assessment to real-time treatment guidance. While the development of these technologies could potentially enhance patient care and healthcare resource utilization, the realization of these benefits requires careful consideration of the current limitations and challenges in the field. The potential for early, accurate diagnosis of organ dysfunction or other complications leading to timely or even pre-emptive treatment is an intriguing prospect but must be approached with rigorous validation and proper scrutiny to ensure improved outcomes and resource efficiency.

Significant challenges exist, as highlighted by our review, which revealed important biases and limitations in the current application of machine learning. Until these challenges are overcome, they will impede broad implementation. An overarching strategy is needed to guide the development and application of machine learning. The United Kingdom Department of Health and Social Care issued a code of conduct in 2018, while the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has developed a regulatory framework and action plan. The primary aim of these initiatives is to establish a reliable structure that ensures secure and efficient integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning technologies in the healthcare domain.96,149–151 These documents cover aspects such as patient consent for data usage, appropriate handling of data, the need for algorithmic transparency, and accountability. Ethical and legal barriers necessitate structured design and deployment. Since these technologies are intended to assist patients, their future development will necessitate collaboration with policymakers, bioethicists, lawyers, academics, clinicians, patients, and society at large.

Research Support

Supported by funds from the Cleveland Clinic London Hospital, London, United Kingdom (to Dr. Arina). Supported in part by the Wellcome/EPSRC Center for Interventional and Surgical Sciences at University College London (London, United Kingdom) under grant Nos. 203145Z/16/Z and NS/A000050/1 (to Dr. Mazomenos).

Competing Interests

Dr. Mazomenos is a shareholder in Medoron Ltd. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Supplemental Digital Content

Supplemental Table 1. Summary of data extracted for each article included in the systematic review with a focus on features, outcomes and limitations stated, https://links.lww.com/ALN/D308.

Supplemental Table 2. Summary of Risk of Bias and Applicability Assessment for Different Domains According to the PROBAST, https://links.lww.com/ALN/D309.

Supplementary Material

Appendix

The following research query was conducted: ((((“artificial intelligence”[All Fields]) OR (“machine learning” [All Fields])) AND (“perioperative” [All Fields])) OR (“surgery” [All Fields])) OR (“anaesthesia” [All Fields])) OR (“preoperative” [All Fields])))). In addition to the systematic review, manual searches were performed using the main research query and one or more of the following terms: AND pneumonia OR chest infection, AND myocardial infarction OR heart failure, AND sepsis, AND acute kidney injury, AND delirium OR stroke, AND infection, AND intubation, AND length of stay, AND bleeding, AND ileus, AND pain, AND complication, AND wound infection, AND skin and soft tissue infection, AND readmission, AND urinary tract infection, AND hypotension, AND transfusion, AND surgical duration, AND post operative venue, AND neural networks, AND extreme gradient boosting, AND random forest, AND support vector machine, AND NPL, AND generative AI.

Footnotes

Published online first on November 9, 2023.

This article is featured in “This Month in Anesthesiology,” page A1.

Supplemental Digital Content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are available in both the HTML and PDF versions of this article. Links to the digital files are provided in the HTML text of this article on the Journal’s Web site (www.anesthesiology.org).

M.S., E.B.M., and J.W. contributed equally to this work.

The article processing charge was funded by University College London.

Contributor Information

Pietro Arina, Email: pietro.arina@nhs.net;p.arina@ucl.ac.uk.

Maciej R. Kaczorek, Email: maciej.kaczorek.19@alumni.ucl.ac.uk.

Daniel A. Hofmaenner, Email: danielandrea.hofmaenner@usz.ch.

Walter Pisciotta, Email: walter.pisciotta@outlook.com.

Patricia Refinetti, Email: patricia.refinetti@nhs.net.

Mervyn Singer, Email: m.singer@ucl.ac.uk.

Evangelos B. Mazomenos, Email: e.mazomenos@ucl.ac.uk.

John Whittle, Email: john.whittle2@nhs.net.

References

- 1.Grocott MPW, Pearse RM: Perioperative medicine: The future of anaesthesia? Br J Anaesth 2012; 108:723–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rose J, Weiser TG, Hider P, Wilson L, Gruen RL, Bickler SW: Estimated need for surgery worldwide based on prevalence of diseases: Implications for public health planning of surgical services. Lancet Glob Health 2015; 3:S13–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stefani LC, Gamermann PW, Backof A, Guollo F, Borges RMJ, Martin A, Caumo W, Felix EA: Perioperative mortality related to anesthesia within 48 h and up to 30 days following surgery: A retrospective cohort study of 11,562 anesthetic procedures. J Clin Anesth 2018; 49:79–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tjeertes EKM, Ultee KHJ, Stolker RJ, Verhagen HJM, Bastos Gonçalves FM, Hoofwijk AGM, Hoeks SE: Perioperative complications are associated with adverse long-term prognosis and affect the cause of death after general surgery. World J Surg 2016; 40:2581–90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dencker EE, Bonde A, Troelsen A, Varadarajan KM, Sillesen M: Postoperative complications: An observational study of trends in the United States from 2012 to 2018. BMC Surg 2021; 21:1–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.American Society of Anesthesiologists: FAER–Helrich Lecture: Reversing postoperative mortality. 2021. Available at: https://www.asameetingnewscentral.com/anesthesiology-2021/article/21771506/faerhelrich-lecture-reversing-postoperative-mortality. Accessed May 20, 2023.

- 7.Derogar M, Orsini N, Sadr-Azodi O, Lagergren P: Influence of major postoperative complications on health-related quality of life among long-term survivors of esophageal cancer surgery. J Clin Oncol 2012; 30:1615–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moonesinghe SR, Harris S, Mythen MG, Rowan KM, Haddad FS, Emberton M, Grocott MPW: Survival after postoperative morbidity: A longitudinal observational cohort study. Br J Anaesth 2014; 113:977–84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Merkow RP, Shan Y, Gupta AR, Yang AD, Sama P, Schumacher M, Cooke D, Barnard C, Bilimoria KY: A comprehensive estimation of the costs of 30-day postoperative complications using actual costs from multiple, diverse hospitals. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2020; 46:558–64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Merkow RP, Massarweh NN: Looking beyond perioperative morbidity and mortality as measures of surgical quality. Ann Surg 2022; 275:e281–3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mangano DT, Browner WS, Hollenberg M, London MJ, Tubau JF, Tateo IM; Study of Perioperative Ischemia Research Group: Association of perioperative myocardial ischemia with cardiac morbidity and mortality in men undergoing noncardiac surgery. N Engl J Med 1990; 323:1781–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Minto G, Biccard B: Assessment of the high-risk perioperative patient. Contin Educ Anaesth Crit Care Pain 2014; 14:12–7 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tjeertes EKM, Ultee KHJ, Stolker RJ, Verhagen HJM, Bastos Gonçalves FM, Hoofwijk AGM, Hoeks SE: Perioperative complications are associated with adverse long-term prognosis and affect the cause of death after general surgery. World J Surg 2016; 40:2581–90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khuri SF, Henderson WG, DePalma RG, Mosca C, Healey NA, Kumbhani DJ; Participants in the VA National Surgical Quality Improvement Program: Determinants of long-term survival after major surgery and the adverse effect of postoperative complications. Ann Surg 2005; 242:326–41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Finlayson SG, Beam AL, van Smeden M: Machine learning and statistics in clinical research articles—Moving past the false dichotomy. JAMA Pediatr 2023; 177:448–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stones J, Yates D: Clinical risk assessment tools in anaesthesia. BJA Educ 2019; 19:47–53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bzdok D, Altman N, Krzywinski M: Statistics versus machine learning. Nat Methods 2018; 15:233–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wolff RF, Moons KGM, Riley RD, Whiting PF, Westwood M, Collins GS, Reitsma JB, Kleijnen J, Mallett S; PROBAST Group: PROBAST: A tool to assess the risk of bias and applicability of prediction model studies. Ann Intern Med 2019; 170:51–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, McGuinness LA, Stewart LA, Thomas J, Tricco AC, Welch VA, Whiting P, Moher D: The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021; 372:n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Collins GS, Reitsma JB, Altman DG, Moons KGM: Transparent Reporting of a multivariable prediction model for Individual Prognosis Or Diagnosis (TRIPOD): The TRIPOD statement. BMC Med 2015; 13:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berger VW, Alperson SY: A general framework for the evaluation of clinical trial quality. Rev Recent Clin Trials 2009; 4:79–88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Landis JR, Koch GG: The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977; 33:159–74 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moons KGM, Wolff RF, Riley RD, Whiting PF, Westwood M, Collins GS, Reitsma JB, Kleijnen J, Mallett S: PROBAST: A tool to assess risk of bias and applicability of prediction model studies: Explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med 2019; 170:W1–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khalifa M, Magrabi F, Gallego B: Developing a framework for evidence-based grading and assessment of predictive tools for clinical decision support. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2019; 19:207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Collins GS, Dhiman P, Andaur Navarro CL, Ma J, Hooft L, Reitsma JB, Logullo P, Beam AL, Peng L, Calster BV, Smeden M van, Riley RD, Moons KGM: Protocol for development of a reporting guideline (TRIPOD-AI) and risk of bias tool (PROBAST-AI) for diagnostic and prognostic prediction model studies based on artificial intelligence. BMJ Open 2021; 11:e048008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bonde A, Varadarajan KM, Bonde N, Troelsen A, Muratoglu OK, Malchau H, Yang AD, Alam H, Sillesen M: Assessing the utility of deep neural networks in predicting postoperative surgical complications: A retrospective study. Lancet Digit Health 2021; 3:e471–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.MacKay EJ, Stubna MD, Chivers C, Draugelis ME, Hanson WJ, Desai ND, Groeneveld PW: Application of machine learning approaches to administrative claims data to predict clinical outcomes in medical and surgical patient populations. PloS One 2021; 16:e0252585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chae D, Kim NY, Kim HJ, Kim TL, Kang SJ, Kim SY: A risk scoring system integrating postoperative factors for predicting early mortality after major non-cardiac surgery. Clin Transl Sci 2022; 15:2230–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bihorac A, Ozrazgat-Baslanti T, Ebadi A, Motaei A, Madkour M, Pardalos PM, Lipori G, Hogan WR, Efron PA, Moore F, Moldawer LL, Wang DZ, Hobson CE, Rashidi P, Li X, Momcilovic P: MySurgeryRisk: Development and validation of a machine-learning risk algorithm for major complications and death after surgery. Ann Surg 2019; 269:652–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee SW, Lee HC, Suh J, Lee KH, Lee H, Seo S, Kim TK, Lee SW, Kim YJ: Multi-center validation of machine learning model for preoperative prediction of postoperative mortality. NPJ Digit Med 2022; 5:91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fritz BA, Cui Z, Zhang M, He Y, Chen Y, Kronzer A, Abdallah A., Ben, King CR, Avidan MS: Deep-learning model for predicting 30-day postoperative mortality. Br J Anaesth 2019; 123:688–95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hill BL, Brown R, Gabel E, Rakocz N, Lee C, Cannesson M, Baldi P, Olde Loohuis L, Johnson R, Jew B, Maoz U, Mahajan A, Sankararaman S, Hofer I, Halperin E: An automated machine learning-based model predicts postoperative mortality using readily-extractable preoperative electronic health record data. Br J Anaesth 2019; 123:877–86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kitcharanant N, Chotiyarnwong P, Tanphiriyakun T, Vanitcharoenkul E, Mahaisavariya C, Boonyaprapa W, Unnanuntana A: Development and internal validation of a machine-learning-developed model for predicting 1-year mortality after fragility hip fracture. BMC Geriatr 2022; 22:451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McLeod G, Kennedy I, Simpson E, Joss J, Goldmann K: Pilot project for a web-based dynamic nomogram to predict survival 1 year after hip fracture surgery: Retrospective observational study. Interact J Med Res 2022; 11:e34096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yun K, Oh J, Hong TH, Kim EY: Prediction of mortality in surgical intensive care unit patients using machine learning algorithms. Front Med (Lausanne) 2021; 8:621861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee CK, Samad M, Hofer I, Cannesson M, Baldi P: Development and validation of an interpretable neural network for prediction of postoperative in-hospital mortality. NPJ Digit Med 2021; 4:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shin SJ, Park J, Lee SH, Yang K, Park RW: Predictability of mortality in patients with myocardial injury after noncardiac surgery based on perioperative factors via machine learning: Retrospective study. JMIR Med Inform 2021; 9:e32771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen PF, Chen L, Lin YK, Li GH, Lai F, Lu CW, Yang CY, Chen KC, Lin TY: Predicting postoperative mortality with deep neural networks and natural language processing: Model development and validation. JMIR Med Inform 2022; 10:e38241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.COVIDSurg Collaborative: Machine learning risk prediction of mortality for patients undergoing surgery with perioperative SARS-CoV-2: The COVIDSurg mortality score. Br J Surg 2021; 108:1274–92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kristinsson ÆO, Gu Y, Rasmussen SM, Mølgaard J, Haahr-Raunkjær C, Meyhoff CS, Aasvang EK, Sørensen HBD: Prediction of serious outcomes based on continuous vital sign monitoring of high-risk patients. Comput Biol Med 2022; 147:105559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Feng Z, Bhat RR, Yuan X, Freeman D, Baslanti T, Bihorac A, Li X: Intelligent perioperative system: Towards real-time big data analytics in surgery risk assessment. DASC PICom DataCom CyberSciTech 2017; 2017:1254–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brennan M, Puri S, Ozrazgat-Baslanti T, Feng Z, Ruppert M, Hashemighouchani H, Momcilovic P, Li X, Wang DZ, Bihorac A: Comparing clinical judgment with the MySurgeryRisk algorithm for preoperative risk assessment: A pilot usability study. Surgery 2019; 165:1035–45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hofer IS, Lee C, Gabel E, Baldi P, Cannesson M: Development and validation of a deep neural network model to predict postoperative mortality, acute kidney injury, and reintubation using a single feature set. NPJ Digit Med 2020; 3:58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chelazzi C, Villa G, Manno A, Ranfagni V, Gemmi E, Romagnoli S: The new SUMPOT to predict postoperative complications using an artificial neural network. Sci Rep 2021; 11:22692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jeong YS, Kim J, Kim D, Woo J, Kim MG, Choi HW, Kang AR, Park SY: Prediction of postoperative complications for patients of end stage renal disease. Sensors (Basel) 2021; 21:544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xue B, Li D, Lu C, King CR, Wildes T, Avidan MS, Kannampallil T, Abraham J: Use of machine learning to develop and evaluate models using preoperative and intraoperative data to identify risks of postoperative complications. JAMA Netw Open 2021; 4:e212240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zeng S, Li L, Hu Y, Luo L, Fang Y: Machine learning approaches for the prediction of postoperative complication risk in liver resection patients. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2021; 21:371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nudel J, Bishara AM, de Geus SWL, Patil P, Srinivasan J, Hess DT, Woodson J: Development and validation of machine learning models to predict gastrointestinal leak and venous thromboembolism after weight loss surgery: An analysis of the MBSAQIP database. Surg Endosc 2021; 35:182–91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mascarella MA, Muthukrishnan N, Maleki F, Kergoat MJ, Richardson K, Mlynarek A, Forest VI, Reinhold C, Martin DR, Hier M, Sadeghi N, Forghani R: Above and beyond age: Prediction of major postoperative adverse events in head and neck surgery. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 2022; 131:697–703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Peng X, Zhu T, Wang T, Wang F, Li K, Hao X: Machine learning prediction of postoperative major adverse cardiovascular events in geriatric patients: A prospective cohort study. BMC Anesthesiol 2022; 22:284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tan J, Wang Q, Shi W, Liang K, Yu B, Mao Q: A machine learning approach for predicting early phase postoperative hypertension in patients undergoing carotid endarterectomy. Ann Vasc Surg 2021; 71:121–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ko S, Jo C, Chang CB, Lee YS, Moon YW, Youm JW, Han HS, Lee MC, Lee H, Ro DH: A web-based machine-learning algorithm predicting postoperative acute kidney injury after total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2022; 30:545–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Awadalla SS, Winslow V, Avidan MS, Haroutounian S, Kannampallil TG: Effect of acute postsurgical pain trajectories on 30-day and 1-year pain. PLoS One 2022; 17:e0269455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dolendo IM, Wallace AM, Armani A, Waterman RS, Said ET, Gabriel RA: Predictive analytics for inpatient postoperative opioid use in patients undergoing mastectomy. Cureus 2022; 14:e23079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gabriel RA, Harjai B, Prasad RS, Simpson S, Chu I, Fisch KM, Said ET: Machine learning approach to predicting persistent opioid use following lower extremity joint arthroplasty. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2022; 47:313–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gabriel RA, Simpson S, Zhong W, Burton BN, Mehdipour S, Said ET: A neural network model using pain score patterns to predict need for outpatient opioid refills following ambulatory surgery: A retrospective analysis. JMIR Perioper Med 2023; 6:e40455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Castle JP, Jildeh TR, Chaudhry F, Turner EHG, Abbas MJ, Mahmoud O, Hengy M, Okoroha KR, Lynch TS: Machine learning model identifies preoperative opioid use, male sex, and elevated body mass index as predictive factors for prolonged opioid consumption following arthroscopic meniscal surgery. Arthroscopy 2023; 39:1505–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhang Y, Yang D, Liu Z, Chen C, Ge M, Li X, Luo T, Wu Z, Shi C, Wang B, Huang X, Zhang X, Zhou S, Hei Z: An explainable supervised machine learning predictor of acute kidney injury after adult deceased donor liver transplantation. J Transl Med 2021; 19:321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kunze KN, Polce EM, Schwab JH, Levine BR: Development and internal validation of machine learning algorithms for predicting complications after primary total hip arthroplasty. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2023; 143:2181–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bishara A, Wong A, Wang L, Chopra M, Fan W, Lin A, Fong N, Palacharla A, Spinner J, Armstrong R, Pletcher MJ, Lituiev D, Hadley D, Butte A: Opal: An implementation science tool for machine learning clinical decision support in anesthesia. J Clin Monit Comput 2021; 36:1367–77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Filiberto AC, Ozrazgat-Baslanti T, Loftus TJ, Peng Y-C, Datta S, Efron P, Upchurch GR, Jr, Bihorac A, Cooper MA: Optimizing predictive strategies for acute kidney injury after major vascular surgery. Surgery 2021; 170:298–303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lee HC, Yoon SB, Yang SM, Kim WH, Ryu HG, Jung CW, Suh KS, Lee KH: Prediction of acute kidney injury after liver transplantation: Machine learning approaches vs. logistic regression model. J Clin Med 2018; 7:428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Adhikari L, Ozrazgat-Baslanti T, Ruppert M, Madushani RWMA, Paliwal S, Hashemighouchani H, Zheng F, Tao M, Lopes JM, Li X, Rashidi P, Bihorac A: Improved predictive models for acute kidney injury with IDEA: Intraoperative data embedded analytics. PLoS One 2019; 14:e0214904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sobrie O, Lazouni MEA, Mahmoudi S, Mousseau V, Pirlot M: A new decision support model for preanesthetic evaluation. Comput Methods Programs Biomed 2016; 133:183–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bishara A, Chiu C, Whitlock EL, Douglas VC, Lee S, Butte AJ, Leung JM, Donovan AL: Postoperative delirium prediction using machine learning models and preoperative electronic health record data. BMC Anesthesiol 2022; 22:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hu XY, Liu H, Zhao X, Sun X, Zhou J, Gao X, Guan HL, Zhou Y, Zhao Q, Han Y, Cao JL: Automated machine learning-based model predicts postoperative delirium using readily extractable perioperative collected electronic data. CNS Neurosci Ther 2022; 28:608–18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhao H, You J, Peng Y, Feng Y: Machine learning algorithm using electronic chart-derived data to predict delirium after elderly hip fracture surgeries: A retrospective case-control study. Front Surg 2021; 8:634629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jones RN, Tommet D, Steingrimsson J, Racine AM, Fong TG, Gou Y, Hshieh TT, Metzger ED, Schmitt EM, Tabloski PA, Travison TG, Vasunilashorn SM, Abdeen A, Earp B, Kunze L, Lange J, Vlassakov K, Dickerson BC, Marcantonio ER, Inouye SK: Development and internal validation of a predictive model of cognitive decline 36 months following elective surgery. Alzheimers Dement (Amst) 2021; 13:e12201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Racine AM, Tommet D, D’Aquila ML, Fong TG, Gou Y, Tabloski PA, Metzger ED, Hshieh TT, Schmitt EM, Vasunilashorn SM, Kunze L, Vlassakov K, Abdeen A, Lange J, Earp B, Dickerson BC, Marcantonio ER, Steingrimsson J, Travison TG, Inouye SK, Jones RN; RISE Study Group: Machine learning to develop and internally validate a predictive model for post-operative delirium in a prospective, observational clinical cohort study of older surgical patients. J Gen Intern Med 2021; 36:265–73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Song YX, Yang XD, Luo YG, Ouyang CL, Yu Y, Ma YL, Li H, Lou JS, Liu YH, Chen YQ, Cao JB, Mi WD: Comparison of logistic regression and machine learning methods for predicting postoperative delirium in elderly patients: A retrospective study. CNS Neurosci Ther 2023; 29:158–67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bai P, Zhou Y, Liu Y, Li G, Li Z, Wang T, Guo X: Risk factors of cerebral infarction and myocardial infarction after carotid endarterectomy analyzed by machine learning. Comput Math Methods Med 2020; 2020:6217392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tavolara TE, Gurcan MN, Segal S, Niazi MKK: Identification of difficult to intubate patients from frontal face images using an ensemble of deep learning models. Comput Biol Med 2021; 136:104737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Xie T, Jiang Z, Wen C, Shen D, Bian J, Liu S, Deng X, Zha Y: Blood metabolomic profiling predicts postoperative gastrointestinal function of colorectal surgical patients under the guidance of goal-directed fluid therapy. Aging (Albany NY) 2021; 13:8929–43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tourani R, Murphree DH, Melton-Meaux G, Wick E, Kor DJ, Simon GJ: The value of aggregated high-resolution intraoperative data for predicting post-surgical infectious complications at two independent sites. Stud Health Technol Inform 2019; 264:398–402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Li P, Wang Y, Li H, Cheng B, Wu S, Ye H, Ma D, Fang X, Cao Y, Gao H, Hu T, Lv J, Yang J, Yang Y, Zhong Y, Zhou J, Zou X, He M, Li X, Luo D, Wang H, Yu T, Chen L, Wang L, Cai Y, Cao Z, Li Y, Lian J, Sun H, Wang S: Prediction of postoperative infection in elderly using deep learning-based analysis: An observational cohort study. Aging Clin Exp Res 2023; 35:639–47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Du Y, Shi H, Yang X, Wu W: Machine learning for infection risk prediction in postoperative patients with non-mechanical ventilation and intravenous neurotargeted drugs. Front Neurol 2022; 13:942023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Oh AR, Park J, Shin SJ, Choi B, Lee J-H, Lee S-H, Yang K: Prediction model for myocardial injury after non-cardiac surgery using machine learning. Sci Rep 2023; 13:1475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Suhre W, O’Reilly-Shah V, Cleve WV: Cannabis use is associated with a small increase in the risk of postoperative nausea and vomiting: A retrospective machine-learning causal analysis. BMC Anesthesiol 2020; 20:115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zhang L, Yan YR, Li SQ, Li HP, Lin YN, Li N, Sun XW, Ding YJ, Li CX, Li QY: Moderate to severe OSA screening based on support vector machine of the Chinese population faciocervical measurements dataset: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2021; 11:e048482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Walczak S, Velanovich V: Prediction of perioperative transfusions using an artificial neural network. PloS One 2020; 15:e0229450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ren W, Li D, Wang J, Zhang J, Fu Z, Yao Y: Prediction and evaluation of machine learning algorithm for prediction of blood transfusion during cesarean section and analysis of risk factors of hypothermia during anesthesia recovery. Comput Math Methods Med 2022; 2022:8661324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 82.Karri R, Kawai A, Thong YJ, Ramson DM, Perry LA, Segal R, Smith JA, Penny-Dimri JC: Machine learning outperforms existing clinical scoring tools in the prediction of postoperative atrial fibrillation during intensive care unit admission after cardiac surgery. Heart Lung Circ 2021; 30:1929–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Chen C, Yang D, Gao S, Zhang Y, Chen L, Wang B, Mo Z, Yang Y, Hei Z, Zhou S: Development and performance assessment of novel machine learning models to predict pneumonia after liver transplantation. Respir Res 2021; 22:94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Koretsky MJ, Brovman EY, Urman RD, Tsai MH, Cheney N: A machine learning approach to predicting early and late postoperative reintubation. J Clin Monit Comput 2022; 37:501–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bolourani S, Wang P, Patel VM, Manetta F, Lee PC: Predicting respiratory failure after pulmonary lobectomy using machine learning techniques. Surgery 2020; 168:743–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Jungquist CR, Chandola V, Spulecki C, Nguyen KV, Crescenzi P, Tekeste D, Sayapaneni PR: Identifying patients experiencing opioid‐induced respiratory depression during recovery from anesthesia: The application of electronic monitoring devices. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs 2019; 16:186–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kamaleswaran R, Sataphaty SK, Mas VR, Eason JD, Maluf DG: Artificial intelligence may predict early sepsis after liver transplantation. Front Physiol 2021; 12:692667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Cartailler J, Parutto P, Touchard C, Vallée F, Holcman D: Alpha rhythm collapse predicts iso-electric suppressions during anesthesia. Commun Biol 2019; 2:327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hatib F, Jian Z, Buddi S, Lee C, Settels J, Sibert K, Rinehart J, Cannesson M: Machine-learning algorithm to predict hypotension based on high-fidelity arterial pressure waveform analysis. Anesthesiology 2018; 129:663–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wijnberge M, Geerts BF, Hol L, Lemmers N, Mulder MP, Berge P, Schenk J, Terwindt LE, Hollmann MW, Vlaar AP, Veelo DP: Effect of a machine learning-derived early warning system for intraoperative hypotension vs standard care on depth and duration of intraoperative hypotension during elective noncardiac surgery: The HYPE randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2020; 323:1052–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Jacquet-Lagrèze M, Larue A, Guilherme E, Schweizer R, Portran P, Ruste M, Gazon M, Aubrun F, Fellahi JL: Prediction of intraoperative hypotension from the linear extrapolation of mean arterial pressure. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2022; 39:574–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Schenk J, Wijnberge M, Maaskant JM, Hollmann MW, Hol L, Immink RV, Vlaar AP, van der Ster BJP, Geerts BF, Veelo DP: Effect of hypotension prediction index–guided intraoperative haemodynamic care on depth and duration of postoperative hypotension: A sub-study of the Hypotension Prediction trial. Br J Anaesth 2021; 127:681–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Lee S, Lee HC, Chu YS, Song SW, Ahn GJ, Lee H, Yang S, Koh SB: Deep learning models for the prediction of intraoperative hypotension. Br J Anaesth 2021; 126:808–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kendale S, Kulkarni P, Rosenberg AD, Wang J: Supervised machine-learning predictive analytics for prediction of postinduction hypotension. Anesthesiology 2018; 129:675–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Solomon SC, Saxena RC, Neradilek MB, Hau V, Fong CT, Lang JD, Posner KL, Nair BG: Forecasting a crisis: Machine-learning models predict occurrence of intraoperative bradycardia associated with hypotension. Anesth Analg 2020; 130:1201–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Vokinger KN, Gasser U: Regulating AI in medicine in the United States and Europe. Nat Mach Intell 2021; 3:738–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Lundberg SM, Nair B, Vavilala MS, Horibe M, Eisses MJ, Adams T, Liston DE, Low DK, Newman SF, Kim J, Lee SI: Explainable machine-learning predictions for the prevention of hypoxaemia during surgery. Nat Biomed Eng 2018; 2:749–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.van de Sande D, van Genderen ME, Verhoef C, Huiskens J, Gommers D, van Unen E, Schasfoort RA, Schepers J, van Bommel J, Grünhagen DJ: Optimizing discharge after major surgery using an artificial intelligence–based decision support tool (DESIRE): An external validation study. Surgery 2022; 172:663–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Cabrera A, Bouterse A, Nelson M, Razzouk J, Ramos O, Chung D, Cheng W, Danisa O: Use of random forest machine learning algorithm to predict short term outcomes following posterior cervical decompression with instrumented fusion. J Clin Neurosci 2023; 107:167–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Chiew CJ, Liu N, Wong TH, Sim YE, Abdullah HR: Utilizing machine learning methods for preoperative prediction of postsurgical mortality and intensive care unit admission. Ann Surg 2020; 272:1133–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Gabriel RA, Sharma BS, Doan CN, Jiang X, Schmidt UH, Vaida F: A predictive model for determining patients not requiring prolonged hospital length of stay after elective primary total hip arthroplasty. Anesth Analg 2019; 129:43–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.van de Sande D, van Genderen ME, Verhoef C, van Bommel J, Gommers D, van Unen E, Huiskens J, Grünhagen DJ: Predicting need for hospital-specific interventional care after surgery using electronic health record data. Surgery 2021; 170:790–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Li H, Jiao J, Zhang S, Tang H, Qu X, Yue B: Construction and comparison of predictive models for length of stay after total knee arthroplasty: Regression model and machine learning analysis based on 1,826 cases in a single Singapore center. J Knee Surg 2022; 35:7–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Sridhar S, Whitaker B, Mouat-Hunter A, McCrory B: Predicting length of stay using machine learning for total joint replacements performed at a rural community hospital. PLoS One 2022; 17:e0277479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Abbas A, Mosseri J, Lex JR, Toor J, Ravi B, Khalil EB, Whyne C: Machine learning using preoperative patient factors can predict duration of surgery and length of stay for total knee arthroplasty. Int J Med Inform 2022; 158:104670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Gabriel RA, Harjai B, Simpson S, Du AL, Tully JL, George O, Waterman R: An ensemble learning approach to improving prediction of case duration for spine surgery: Algorithm development and validation. JMIR Perioper Med 2023; 6:e39650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Ezuma CO, Lu Y, Pareek A, Wilbur R, Krych AJ, Forsythe B, Camp CL: A machine learning algorithm outperforms traditional multiple regression to predict risk of unplanned overnight stay following outpatient medial patellofemoral ligament reconstruction. Arthrosc Sports Med Rehabil 2022; 4:e1103–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Lu Y, Forlenza E, Cohn MR, Lavoie-Gagne O, Wilbur RR, Song BM, Krych AJ, Forsythe B: Machine learning can reliably identify patients at risk of overnight hospital admission following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2021; 29:2958–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Song BM, Lu Y, Wilbur RR, Lavoie-Gagne O, Pareek A, Forsythe B, Krych AJ: Machine learning model identifies increased operative time and greater BMI as predictors for overnight admission after outpatient hip arthroscopy. Arthrosc Sports Med Rehabil 2021; 3:e1981–90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Bertsimas D, Dunn J, Velmahos GC, Kaafarani HMA: Surgical risk is not linear: Derivation and validation of a novel, user-friendly, and machine-learning-based Predictive OpTimal Trees in Emergency Surgery Risk (POTTER) calculator. Ann Surg 2018; 268:574–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Gao J, Merchant AM: A machine learning approach in predicting mortality following emergency general surgery. Am Surg 2021; 87:1379–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Hechi MWE, Maurer LR, Levine J, Zhuo D, Moheb ME, Velmahos GC, Dunn J, Bertsimas D, Kaafarani HM: Validation of the artificial intelligence-based Predictive Optimal Trees in Emergency Surgery Risk (POTTER) calculator in emergency general surgery and emergency laparotomy patients. J Am Coll Surg 2021; 232:912–9.e1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Xue Q, Wen D, Ji MH, Tong J, Yang JJ, Zhou CM: Developing machine learning algorithms to predict pulmonary complications after emergency gastrointestinal surgery. Front Med (Lausanne) 2021; 8:655686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Mišić VV, Gabel E, Hofer I, Rajaram K, Mahajan A: Machine learning prediction of postoperative emergency department hospital readmission. Anesthesiology 2020; 132:968–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Castela Forte J, Mungroop HE, de Geus F, van der Grinten ML, Bouma HR, Pettilä V, Scheeren TWL, Nijsten MWN, Mariani MA, van der Horst ICC, Henning RH, Wiering MA, Epema AH: Ensemble machine learning prediction and variable importance analysis of 5-year mortality after cardiac valve and CABG operations. Sci Rep 2021; 11:3467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Castela Forte J, Yeshmagambetova G, Van Der Grinten ML, Scheeren TWL, Nijsten MWN, Mariani MA, Henning RH, Epema AH: Comparison of machine learning models including preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative data and mortality after cardiac surgery. JAMA Netw Open 2022; 5:E2237970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Shi S, Lei G, Yang L, Zhang C, Fang Z, Li J, Wang G: Using machine learning to predict postoperative liver dysfunction after aortic arch surgery. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2021; 35:2330–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Gao Y, Liu X, Wang L, Wang S, Yu Y, Ding Y, Wang J, Ao H: Machine learning algorithms to predict major bleeding after isolated coronary artery bypass grafting. Front Cardiovasc Med 2022; 9:881881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Tschoellitsch T, Böck C, Mahečić TT, Hofmann A, Meier J: Machine learning-based prediction of massive perioperative allogeneic blood transfusion in cardiac surgery. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2022; 39:766–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Lee HC, Yoon HK, Nam K, Cho YJ, Kim TK, Kim WH, Bahk JH: Derivation and validation of machine learning approaches to predict acute kidney injury after cardiac surgery. J Clin Med 2018; 7:322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Li T, Yang Y, Huang J, Chen R, Wu Y, Li Z, Lin G, Liu H, Wu M: Machine learning to predict post-operative acute kidney injury stage 3 after heart transplantation. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2022; 22:288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Petrosyan Y, Mesana TG, Sun LY: Prediction of acute kidney injury risk after cardiac surgery: Using a hybrid machine learning algorithm. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2022; 22:137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Jiang H, Liu L, Wang Y, Ji H, Ma X, Wu J, Huang Y, Wang X, Gui R, Zhao Q, Chen B: Machine learning for the prediction of complications in patients after mitral valve surgery. Front Cardiovasc Med 2021; 8:771246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Li XF, Huang YZ, Tang JY, Li RC, Wang XQ: Development of a random forest model for hypotension prediction after anesthesia induction for cardiac surgery. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9:8729–39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Park K, Kim NY, Kim KJ, Oh C, Chae D, Kim SY: A simple risk scoring system for predicting the occurrence of aspiration pneumonia after gastric endoscopic submucosal dissection. Anesth Analg 2022; 134:114–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Roberts M, Driggs D, Thorpe M, Gilbey J, Yeung M, Ursprung S, Aviles-Rivero AI, Etmann C, McCague C, Beer L, Weir-McCall JR, Teng Z, Gkrania-Klotsas E, Ruggiero A, Korhonen A, Jefferson E, Ako E, Langs G, Gozaliasl G, Yang G, Prosch H, Preller J, Stanczuk J, Tang J, Hofmanninger J, Babar J, Sánchez LE, Thillai M, Gonzalez PM, Teare P, Zhu X, Patel M, Cafolla C, Azadbakht H, Jacob J, Lowe J, Zhang K, Bradley K, Wassin M, Holzer M, Ji K, Ortet MD, Ai T, Walton N, Lio P, Stranks S, Shadbahr T, Lin W, Zha Y, Niu Z, Rudd JHF, Sala E, Schönlieb C-B: Common pitfalls and recommendations for using machine learning to detect and prognosticate for COVID-19 using chest radiographs and CT scans. Nat Mach Intell 2021; 3:199–217 [Google Scholar]

- 127.Brabec J, Komárek T, Franc V, Machlica L: On model evaluation under non-constant class imbalance. International Conference on Computational Science. Switzerland, Springer, 2020, pp. 74–87 [Google Scholar]

- 128.Fawcett T: ROC graphs: Notes and practical considerations for researchers. Pattern Recognit Lett 2004; 31:1–38 [Google Scholar]

- 129.McNelis J, Castaldi M: The National Surgery Quality Improvement Project (NSQIP): A new tool to increase patient safety and cost efficiency in a surgical intensive care unit. Patient Saf Surg 2014; 8:19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Fernandes MPB, Armengol de la Hoz M, Rangasamy V, Subramaniam B: Machine learning models with preoperative risk factors and intraoperative hypotension parameters predict mortality after cardiac surgery. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2021; 35:857–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Chen C, Chen B, Yang J, Li X, Peng X, Feng Y, Guo R, Zou F, Zhou S, Hei Z: Development and validation of a practical machine learning model to predict sepsis after liver transplantation. Ann Med 2023; 55:624–33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Kang AR, Lee J, Jung W, Lee M, Park SY, Woo J, Kim SH: Development of a prediction model for hypotension after induction of anesthesia using machine learning. PLoS One 2020; 15:e0231172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Maheshwari K, Buddi S, Jian Z, Settels J, Shimada T, Cohen B, Sessler DI, Hatib F: Performance of the Hypotension Prediction Index with non-invasive arterial pressure waveforms in non-cardiac surgical patients. J Clin Monit Comput 2021; 35:71–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.West E, Mutasa S, Zhu Z, Ha R: Global trend in artificial intelligence-based publications in radiology from 2000 to 2018. Am J Roentgenol 2019; 213:1204–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Weissler EH, Naumann T, Andersson T, Ranganath R, Elemento O, Luo Y, Freitag DF, Benoit J, Hughes MC, Khan F, Slater P, Shameer K, Roe M, Hutchison E, Kollins SH, Broedl U, Meng Z, Wong JL, Curtis L, Huang E, Ghassemi M: The role of machine learning in clinical research: Transforming the future of evidence generation [published correction appears in Trials 2021; 22:593]. Trials 2021; 22:537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Ramspek CL, Jager KJ, Dekker FW, Zoccali C, van Diepen M: External validation of prognostic models: What, why, how, when and where? Clin Kidney J 2021; 14:49–58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]