Abstract

Objectives

The community-based, longitudinal, Canadian HIV Women’s Sexual and Reproductive Health Cohort Study (CHIWOS) explored the experiences of women with HIV in Canada over the past decade. CHIWOS’ high-impact publications document significant gaps in the provision of healthcare to women with HIV. We used concept mapping to analyse and present a summary of CHIWOS findings on women’s experiences navigating these gaps.

Design

Concept mapping procedures were performed in two steps between June 2019 and March 2021. First, two reviewers (AY and PM) independently reviewed CHIWOS manuscripts and conference abstracts written before 1 August 2019 to identify main themes and generate individual concept maps. Next, the preliminary results were presented to national experts, including women with HIV, to consolidate findings into visuals summarising the experiences and care gaps of women with HIV in CHIWOS.

Setting

British Columbia, Ontario and Quebec, Canada.

Participants

A total of 18 individual CHIWOS team members participated in this study including six lead investigators of CHIWOS and 12 community researchers.

Results

Overall, a total of 60 peer-reviewed manuscripts and conference abstracts met the inclusion criteria. Using concept mapping, themes were generated and structured through online meetings. In total, six composite concept maps were co-developed: quality of life, HIV care, psychosocial and mental health, sexual health, reproductive health, and trans women’s health. Two summary diagrams were created encompassing the concept map themes, one for all women and one specific to trans women with HIV. Through our analysis, resilience, social support, positive healthy actions and women-centred HIV care were highlighted as strengths leading to well-being for women with HIV.

Conclusions

Concept mapping resulted in a composite summary of 60 peer-reviewed CHIWOS publications. This activity allows for priority setting to optimise care and well-being for women with HIV.

Keywords: HIV & AIDS, Health Equity, Patient-Centered Care, Quality in health care

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY.

The study comprehensively summarises the health experiences of women with HIV enrolled in the Canadian HIV Women’s Sexual and Reproductive Health Cohort Study (CHIWOS) and identifies potential gaps in their care.

A diverse group of women and HIV experts across Canada took part in this study to provide feedback on the concept maps which used results from 60 peer-reviewed publications by, with and for women with HIV.

Between June 2019 and March 2021, the process of concept mapping and reviewing visualisations with key informants occurred, with a cut-off date of 1 August 2019 for new publications; however, manuscripts under review or nearing publication were considered and all have since been published.

Although efforts were made to engage team members from all provinces included in the CHIWOS study, community researchers from Ontario and British Columbia only agreed to take part in this study, though academic researchers from Quebec participated.

Introduction

Recent studies have found that women with HIV experience unique health and social needs that differ from those of men with HIV and limit their access to treatment and care services.1–3 The historical lack of research focusing on the realities of women with HIV may be detrimental to their health.4 5 These circumstances led to the development and implementation of the Canadian HIV Women’s Sexual and Reproductive Health Cohort Study (CHIWOS)—the largest community-based study in Canada exploring the experiences and priorities of a diverse, national cohort of women with HIV in British Columbia (BC), Ontario (ON) and Quebec (QC) from 2013 to 2018.

CHIWOS was initiated in 2011 through a qualitative phase, which informed the creation of an in-depth survey.1 2 The study’s objectives were to examine women’s access to women-centred HIV care and the impact of corresponding usage patterns on health outcomes.2 CHIWOS was guided by principles of equitable involvement of those affected by the research in the research process by establishing community-academic partnerships and shared decision-making throughout the study.6 7 This research approach, reflecting community-based research values, was enacted in part through the involvement of women with HIV as trained community researchers to conduct research activities in each stage of the project.2 8 9 CHIWOS was created by, with and for women with HIV in collaboration with academic researchers, clinicians and community partners to investigate women’s mental, sexual and reproductive healthcare priorities, and need for a women-centred HIV care model.1 2 10 Cohort data collection was launched in 2013 and collected at three time points, 18 months apart, from August 2013 to September 2018. A complete description of CHIWOS can be found at www.chiwos.ca. As of publication acceptance, CHIWOS remains the largest longitudinal study of women with HIV in Canada, successfully enrolling a diverse cohort of 1422 women with HIV (356 from BC (25%), 713 from ON (50%) and 353 from QC (25%)).1 2

As of August 2019, a total of 113 publications (53 manuscripts and 60 conference abstracts) had been written using CHIWOS data. This academic content explores dozens of specific topics related to the experiences of women with HIV, including psychosocial determinants, clinical, mental, sexual and reproductive health outcomes, as well as access to, and quality of healthcare that characterise women’s health gaps and needs and that can be used to inform programming and policy in Canada. In an effort to better understand the main topics and gaps of CHIWOS manuscripts and conference abstracts, this study applied Novak and Gowin’s11 concept mapping methodology. The goal of this methodology was to visualise concepts of CHIWOS findings in a hierarchical fashion, with the most inclusive and general concepts at the top of the map, and specific concepts arranged hierarchically below to represent the inter-related relationships in each publication included. We sought to apply these findings towards the creation of a summary diagram to summarise the health experiences and gaps of women with HIV enrolled in CHIWOS. An added benefit of using concept mapping in this study is that the simplistic visualisations allowed for increased accessibility of the CHIWOS findings to those outside of academia, including some community members and knowledge users, which enabled shared decision-making to inform the final product. Our goal was to use these findings to characterise women with HIV’s healthcare needs and gaps to inform policy and programming in Canada.

Methods

Concept mapping is a graphical methodology used to organise and present knowledge. Since its conception by Novak,12 it has been adapted in qualitative research to present findings and analyse themes.13 14 This methodology was chosen to illustrate the key themes from the CHIWOS publications, including both manuscripts and conference abstracts, and their relation to each other in order to demonstrate the experiences and related gaps in care women with HIV face in Canada. We used a social-ecological perspective to understand the interplay between multi-level factors impacting women with HIV, their community and society.15–17

For this study, the concept mapping process from Novak18 was used and encompassed five steps.

Step 1: Conduct a thematic analysis on CHIWOS publications and summarise key findings

All CHIWOS publications (including manuscripts and conference abstracts) published, under review or near publication submission before 1 August 2019 were examined alongside inclusion criteria developed by the core concept team (including AY, MK, MRL and PM). To be included for review, manuscripts were to (1) include national quantitative CHIWOS questionnaire data and (2) be published, under review or near submission in a peer-reviewed journal (manuscripts) or be presented at an HIV-related conference (abstracts) by the exclusion date.

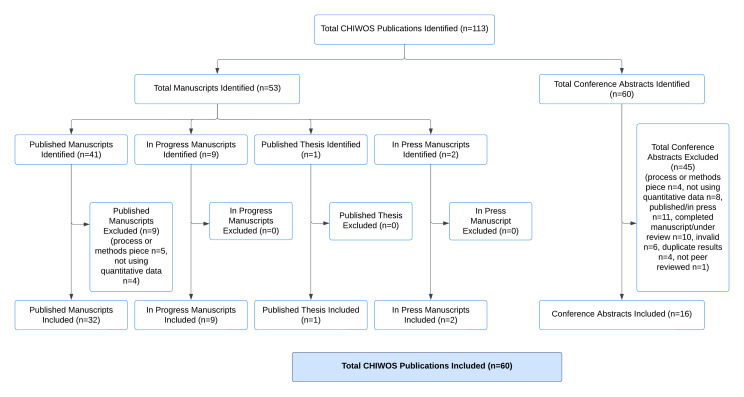

Manuscripts that did not use quantitative CHIWOS data or were process or methods pieces were excluded. For conference abstracts, those which had been published or submitted as manuscripts, showed duplicate results to other abstracts, or were not peer-reviewed prior to conference presentation were excluded. Figure 1 shows the selection process. The inclusion and exclusion criteria were designed to ensure a comprehensive and representative analysis, encompassing all eligible manuscripts or conference abstracts, thereby mitigating the potential for bias or skew in the publication list. A total of 113 CHIWOS publications (including manuscripts and conference abstracts) were reviewed, of which 53 were excluded. This resulted in 60 eligible publications that met the inclusion criteria (summarised in table 1). Eligible publications were grouped together by their overarching theme (discussed further in step 3).

Figure 1.

Applying the eligibility criteria to Canadian HIV Women’s Sexual and Reproductive Health Cohort Study (CHIWOS) publications.

Table 1.

Summary of included Canadian HIV Women’s Sexual and Reproductive Health Cohort Study publications

| Composite concept map theme | Manuscripts (n=44) | Conference abstracts (n=16) |

| Quality of life | n=4 | |

| (a) Logie, Wang et al 2018 Carter, Loutfy et al 2018 Kteily-Hawa, Andany et al 2019 Kteily-Hawa, Warren et al 2019 |

||

| HIV care | n=8 | n=4 |

| Kennedy, Mellor et al 2020 Kerkerian, Kestler et al 2018 (a) Kronfli, Lacombe-Duncan et al 2017 (b) Kronfli, Lacombe-Duncan et al 2017 (b) Logie, Wang et al 2018 Loutfy, de Pokomandy et al 2017 O’Brien, Godard-Sebillotte et al 2019 (a) Shokoohi, Bauer et al 2019 |

Conway, Gormley et al 2019 Kaida, Conway et al 2019 Loutfy, de Pokomandy et al 2015 Puskas, Pick et al 2018 |

|

| Psychosocial and mental health | n=14 | n=5 |

| Carter, Roth et al 2018 Churchill 2018 Gormley, Nicholson et al 2021 Heer, Kaida et al 2022 Jaworsky, Logie et al 2018 (a) Logie, Lacombe-Duncan et al 2018 Logie, Marcus et al 2019 (c) Logie, Wang et al 2018 Logie, Williams et al 2019 Patterson, Nicholson et al 2020 Shokoohi, Bauer et al 2018 (b) Shokoohi, Bauer et al 2019 (c) Shokoohi, Bauer et al 2019 Wagner, Jaworsky et al 2018 |

Kaida, Nicholson et al 2019 (a) Logie, Wang et al 2019 (b) Logie, Wang et al 2019 Parry, Lee et al 2019 Underhill, Wu et al 2018 |

|

| Sexual health | n=8 | n=2 |

| (a) Carter, Greene et al 2018 (b) Carter, Greene et al 2018 Carter, Greene et al 2019 Carter, Patterson et al 2020 de Pokomandy, Burchell et al 2019 Kaida, Carter et al 2015 Logie, Kaida et al 2020 Patterson, Carter et al 2017 |

Salters, Loutfy et al 2015 Underhill, Kennedy et al 2017 |

|

| Reproductive health | n=6 | n=4 |

| Andany, Kaida et al 2020 Fortin-Hughes, Proulx-Boucher et al 2019 Kaida, Patterson et al 2017 Salters, Loutfy et al 2017 Skeritt L, de Pokomandy et al 2021 Valiaveetil, Loutfy et al 2019 |

Boucoiran, Kaida et al 2019 Kaida, Gormley et al 2019 Kaida, Money et al 2017 Siou, Salters et al 2016 |

|

| Trans women with HIV | n=4 | n=1 |

| Lacombe-Duncan, Bauer et al 2019 Lacombe-Duncan, Newman et al 2017 Lacombe-Duncan, Warren et al 2021 (b) Logie, Lacombe-Duncan et al 2018 |

Lacombe-Duncan, Persad et al 2017 |

See online supplemental material for full citations.

bmjopen-2023-078833supp001.pdf (3MB, pdf)

From the 60 included manuscripts and conference abstracts, we began by identifying the major findings of each that answered the guiding question: what characterises the healthcare gaps and needs of CHIWOS participants? We examined publications to identify themes related to gaps in care, as well as explicit findings related to healthcare access and quality. We then used the coding step of a thematic analysis19 to code the findings into their simplest form (eg, lower food security is associated with increased substance use). As a last step, we listed the concepts and linking words within each code (eg, concepts=lower food security, substance use; linking words=is associated with).19 This process was repeated for each manuscript and conference abstract. In our efforts to mitigate theme over-representation, we opted to include an abstract only when a corresponding manuscript was not available. However, given the inherent intersectionality of the data, there may be instances where subsets of the data were presented in multiple publications. A thorough exploration of such cases is provided in the discussion section for clarity and transparency.

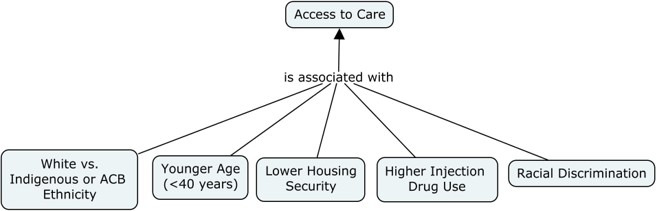

Step 2: Individual concept mapping of CHIWOS manuscripts and abstracts

The concepts and linking words from step 1 were used to guide the design of 60 individual concept maps, each visually summarising the key findings of one manuscript or conference abstract. Figure 2 is an example of one of the individual concept maps we created from the CHIWOS findings.

Figure 2.

Example of an individual concept map from one publication (Access to Care, Kronfli et al 36).

Within each map, concepts were listed in hierarchical order with the most overarching general concepts at the top and the most specific concepts at the bottom.11 Using an online software, CMAPTools,20 concepts were designated by boxes and lines were drawn from one concept to another with the linking words placed in between. We adapted the concept map process by adding in extra features that better visually represent the CHIWOS findings. For example, arrowheads pointed towards outcomes of CHIWOS findings. Bidirectional arrows were used when a relationship was present between two outcomes. Solid lines represented a positive association between concepts while dotted lines represented a negative association between concepts. Concepts that recurred in two or more individual concept maps were considered critical findings and were designated by a blue shaded concept box.

AY and PM independently reviewed each concept map to ensure all major findings were represented and summarised into the visual. If there was a discrepancy, a third reviewer (MRL) was consulted to make the final decision.

Step 3: Compilation of individual concept maps into composite concept maps

AY, PM and MRL grouped the maps with main concepts and similar themes together. Six major themes were identified: quality of life, HIV care, psychosocial and mental health, sexual health, reproductive health, and trans women with HIV.

The individual concept maps that fell under each major theme were compiled together to create a composite concept map. AY and PM drew cross-links between concepts that had relationships, but were on different domains of the composite concept map.14 This process was repeated for each theme and six composite concept maps were developed.

Step 4: Internal development team review and brainstorming of overarching visualisation

An internal team (including AY, MK, MRL and PM) meeting was held in August 2019 to review all six composite concept maps. The goal was to ensure all key findings were represented on the maps with good readability. The guiding question was referred to when deciding to remove or add concepts to the map. The team then brainstormed ideas to design a compilation visual representing the findings of the six composite maps that answered our guiding research question. A preliminary sketch was formed which is now referred to as the summary diagram.

Step 5: External expert team review and validation

The first author of each included CHIWOS manuscript and conference abstract (hereafter referred to as lead investigators), and all CHIWOS community researchers were identified as potential key participants in this study and were approached for recruitment from October 2019 to November 2020. Over 30 CHIWOS lead investigators and community team members from all three provinces were invited to participate in the study by email, of which 18 agreed to participate. A total of 29 meetings were held with groups of participants and took place both in-person and virtually.

For orientation, introductory slides explaining the concept mapping methodology and its application to CHIWOS findings were shown to the group. Each of the six composite concept maps were then presented. Lead investigators were asked to ensure that all major CHIWOS findings were accurate and present, and community researchers were asked to ensure that the experiences of women with HIV were accurately represented. All participants were asked to provide input on the readability, clarity and inclusivity of language. Next, the summary diagram was presented, and participants were asked to ensure that all key components from the composite concept maps were included in the summary diagram, in addition to providing feedback on design features including colour, layout and display of content. All participant feedback was documented and the feedback between different focus groups were compared. All suggestions and changes were reviewed by AY and PM through revisiting the manuscript and abstracts and addressing the guiding research question. Updated composite theme maps and the summary diagrams were presented at a follow-up meeting and consensus was reached by discussion.

Patient and public involvement

Evidently, women with HIV (community researchers; those previously involved in the CHIWOS project) were involved in the study. Their invaluable insights significantly contributed to the thematic analysis and individual concept mapping, offering a nuanced perspective on healthcare gaps and needs. Additionally, their active participation in validating composite concept maps and the summary diagram guaranteed precision and inclusivity in the representation of findings. In recognition of their contributions, all community members involved were appropriately compensated for their time and expertise.

Results

A total of 18 individuals participated in the design and review of the concept maps, including 6 lead investigators (BC: n=1; ON: n=3; QC: n=2), and 12 community researchers (BC: n=5; ON: n=7). All participants identified as cis or trans women.

Composite concept maps

Overall, six composite maps were created (see online supplemental figures 1–6).

We developed composite concept map 1 (see online supplemental figure 1) from four manuscripts focused on the topic of quality of life. Notable findings in this map include bidirectional association of physical and mental health quality of life, and the association of experiences of women-centred HIV care with higher resilience and in turn higher quality of life. This map illustrates the influence socioeconomic status, experiences of stigma, sexual orientation, substance use, social support and relationship status have on mental and physical health-related quality of life.

From eight manuscripts and four conference abstracts, composite concept map 2 (see online supplemental figure 2) was created to illustrate findings related to HIV care. This map demonstrates associations between several aspects of HIV care including viral suppression, use of combination antiretroviral therapy (cART), care access and attrition. Notable findings include the effect having social and peer support have on increasing access to HIV care and the effect of racial discrimination on care attrition. Experiencing violence in adulthood was found to reduce cART use and adherence, leading to reduced viral suppression. On the other hand, peer leadership involvement was associated with higher awareness of cART prevention benefits.

Composite concept map 3 (see online supplemental figure 3) demonstrates the connections between various facets of psychosocial and mental health and represents data from 14 manuscripts and five abstracts. Indigenous heritage was associated with experiencing higher violence in adulthood as well as lower housing security and income. Lower food security was associated with higher substance use. This map emphasises the negative impact of intersectional stigma on all aspects of mental health, which are associated with clinical measures like a lack of cART initiation.

The most complex of the six visuals is a composite concept map 4 (see online supplemental figure 4) which explores sexual health experiences of women enrolled in CHIWOS. This map represented data from eight manuscripts and two abstracts. Its findings were organised into social and medical aspects of sexual health subcategories. A main finding was the association of higher depression and experienced violence in adulthood with lower pleasure and satisfaction in relationships. Higher HIV-related stigma was also associated with higher sexual inactivity in the past 6 months, which was a recurring theme in the included publications.

The fifth composite concept map (see online supplemental figure 5) showed CHIWOS findings related to reproductive health. The production of this map as separate from sexual health was intentional to illustrate that for many women, sexual health goes beyond reproductive health desires or lack thereof. This map drew on data from six manuscripts and four abstracts, and includes subcategories of menstruation, pregnancy, contraceptive use and early menopause. Findings showed low use of a narrow range of contraceptive methods, with sexual orientation, previous pregnancies and age influencing contraceptive choice. Service provider counselling on choices for infant feeding practices, support, and free formula programmes were associated with positive infant feeding experiences for women.

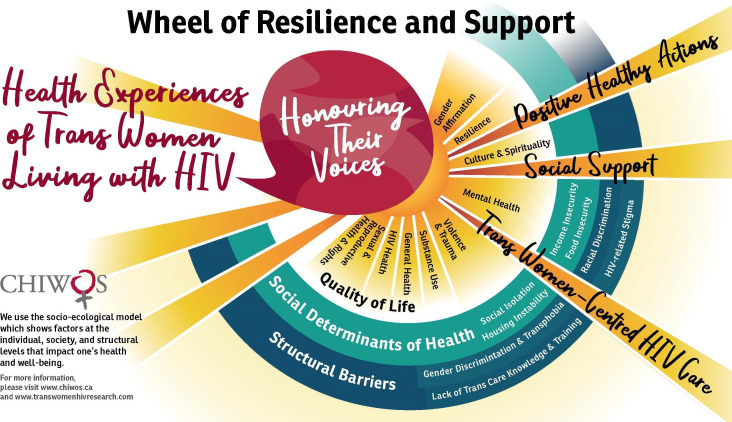

The final map titled Trans Women Concept Map (see online supplemental figure 6) included topics from all five of the other composite concept maps but from the exclusive perspective of trans women in CHIWOS, with data drawn from four manuscripts and one abstract that solely analysed trans women’s data. This map shows trans women’s experiences of gender discrimination and transphobia, which influence barriers to gender affirming and general HIV care, with HIV-related stigma playing a significant role in this association. Higher sexual relationship power was associated with lower depression and post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms. Higher social support was associated with resilience, which trans women reported higher levels of than cis women in CHIWOS.

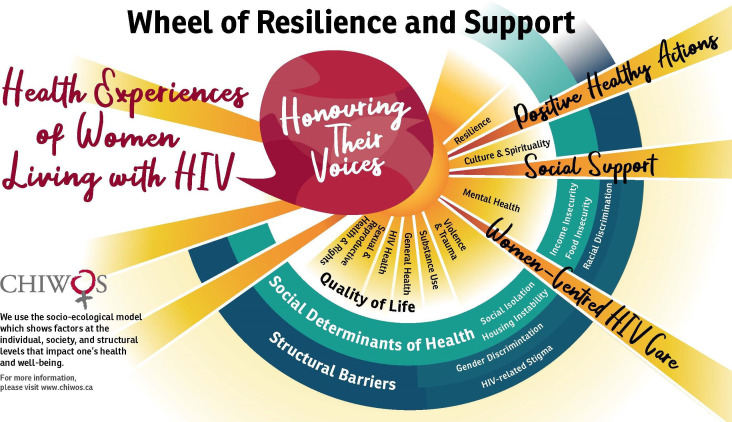

Summary diagrams

From the six composite concept maps, two summary diagrams were created (see figures 3 and 4), one for all women and one for trans women specifically. These diagrams provide a summary of the key insights, barriers, and supports that affect the health and well-being of women with HIV involved in CHIWOS. Through actively participating in the arts-based design process of the two summary diagrams, community researchers played a vital role in shaping both the overall themes presented and the final visual of the diagrams. They insisted on grounding the diagrams in the stories and experiences of CHIWOS participants, highlighting the importance of making them accessible, empowering, holistic, authentic and inclusive—these specific terms were consistently used by community researchers during our collaborative meetings as we worked together on developing the diagrams. The meaningful engagement of community researchers (who collected the CHIWOS data) ensured women with HIV were represented and involved in shared decision-making in the creation of these diagrams.

Figure 3.

Canadian HIV Women’s Sexual and Reproductive Health Cohort Study (CHIWOS) summary diagram—honouring the experiences of women with HIV.

Figure 4.

Canadian HIV Women’s Sexual and Reproductive Health Cohort Study (CHIWOS) summary diagram—honouring the experiences of trans women living with HIV.

We used a socio-ecological model in developing the summary diagrams to show how the individual, societal and structural factors present in the concept maps intersect to affect women’s health and well-being.11–13 To visually represent this intersection, the diagram was created in the shape of concentric circles. At the centre of both visuals is a speaking bubble highlighting the stories that women who participated in CHIWOS shared and was named by the community researchers: ‘Honouring Their Voices’. The inner circle of both figures highlights the aspects that are important to women’s quality of life: HIV health, general health including physical, health, sexual and reproductive health, mental health, violence and trauma, substance use, culture and spirituality, and resilience. Surrounding quality of life are social factors that combine to affect the health of individuals and their communities, such as housing stability, food security, income and social isolation. The outer circle consists of the structural factors that affect health including HIV-related stigma, and gender and racial discrimination. Intersecting these layers of the women’s health experiences are the important ways women are addressing barriers in their lives, including through social support, accessing or calling to action the need for women-centred HIV care, and positive healthy actions.

Through consultations with a trans woman advocate and CHIWOS team member, the second summary diagram (see figure 4) was created to reflect the most important and recurring findings of the concept mapping exercise as they relate to the experiences of trans women with HIV involved in CHIWOS. The main difference from figure 3 is the addition of gender affirmation in the inner circle in reference to trans women’s experiences. Community researchers define gender affirmation whereby an individual receives the affirmation they desire with respect to their gender identity and expression from those around them, including social recognition and/or medical access to care such as hormone therapy and gender-affirming surgeries.

Together, the composite concept maps show that there are both commonalities and differences in the experiences of women with HIV; however, resilience was present among all CHIWOS participants.

Through facilitated discussions with The Public Studio, an activist design studio in Toronto (https://thepublicstudio.ca/), we identified that community partners wanted: (1) a sun to be a theme of the visuals that radiates energetically from the centre of the diagram and (2) a strength-based title such as the ‘Wheel of Resilience and Support’. It was important to the community partners that the visuals served as an invitation to translate the stories of CHIWOS participants into action.

Discussion

The six composite concept maps and two summary diagrams show a decade of work done by the CHIWOS team, providing a dynamic mosaic of information representative of the intricacies of women’s experiences.11–13 The co-creation of concept maps, distinct from traditional systematic reviews, offers an innovative and valuable approach to understanding the health experiences of women with HIV, providing novel insights that extend beyond individual publications for a more comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the multifaceted experiences of women who participated in CHIWOS. The integration of cross-cutting themes like women-centred HIV care and the importance of positive healthy actions in the summary diagram visually emphasises the most crucial issues for future research, thus contributing to the advancement of policy and programming for women with HIV in Canada.

A main strength of this study is the richness of CHIWOS dataset analyses conducted over the last 10 years. This study included publications from diverse authors and perspectives and focused on different topics and subsets of the CHIWOS participant population. This increased the reliability of the findings and ensured a full picture of the CHIWOS population’s experiences was represented in the concept maps. Further strengthening this representation was the iterative and community-based nature of the concept mapping process itself. The process was driven by a diverse group of community members who amended the maps and diagrams through several rounds of consultations, which ensured their accuracy. While we recognise that the inclusion of publications under review or nearing publication may be perceived as a potential limitation due to the absence of peer review, we primarily interpret this as a strength. This decision allowed us to account for the inherent time lag between research analysis and formal publication, ensuring our analysis captures both established and emerging insights in the field. Furthermore, all ‘in progress’ manuscripts included in this analysis have since been published, affirming the validity of our conclusions.

To prevent theme over-representation, we carefully examined the content of each conference abstract and publication to ensure duplicate results were not included. Some publications covered similar themes, such as disclosure, pregnancy loss, cervical cancer disparities, women-centred HIV care, help-seeking, the relationship between stigma and other factors, conception in serodiscordant couples, and issues specific to trans women. However, there were nuanced differences with each of these themes. For instance, the conference abstract focused on disclosure specifically addresses disclosure worries as a factor contributing to health outcomes, while the manuscripts explore experienced child abuse as a determinant of barriers to disclosure and awareness of the criminalisation of disclosure. We find including these nuanced distinctions valuable, as concepts recurring in two or more composite concept maps were considered critical findings. Our rigorous approach to highlight crucial findings without data over-representation is a key strength of this study.

The co-creation of separate composite concept maps for cis and trans women shows the important similarities and differences between cis and trans women’s experiences, and provides a unique perspective not explored in the individual concept maps. Our findings show many similarities in the health experiences of cis and trans women with HIV in CHIWOS were shared.21 This is important for providers who often assume providing care to trans women with HIV requires a unique skillset and approach.22 The key differences in the summary diagrams were gender affirmation at the individual level, as well as trans care knowledge and training at the structural level. Obtaining training in trans health and gender affirmation is a manageable goal that providers can achieve to deliver more competent care to trans women with HIV.23

There are some limitations of this study. Efforts were made to engage lead investigators and community researchers from all provinces included in the CHIWOS study, but only academic researchers (not community researchers) from Quebec participated in this study. However, six manuscripts were included in production of the composite concept maps in which the first author was from Quebec and community members were involved in coauthoring these publications. In shaping our study, we intentionally excluded manuscripts exclusively featuring qualitative data; a decision that might be seen as constraining the incorporation of certain insights. This choice was driven by the inherent challenges of equitably integrating qualitative and quantitative data, especially given the marked difference in sample sizes between the two types of manuscripts. To mitigate this limitation, we extensively involved community researchers in the concept mapping and summary diagram creation process, ensuring a comprehensive approach.

Recently, fellow CHIWOS investigators also employed mapping techniques to examine the experiences of women with HIV in accessing care. Skerritt et al 24 used Fuzzy Cognitive Mapping, a participatory research method, to identify factors influencing satisfaction with HIV care and to understand engagement in the HIV care cascade. The Summary Fuzzy Cognitive Map they produced shows the weightings of categories influencing satisfaction of care, with the most significant being feeling safe and supported by healthcare providers, accessible services, and healthcare provider expertise.24 These mirror some of our findings in our composite concept maps 2 and 6 which show the relationships among access to care, comprehensive care, and feelings of stigma. Both studies offer valuable visual insights into women’s experiences, complementing each other and contributing to a comprehensive understanding when interpreted together.

Our study delved into the nuanced experiences of women with HIV through the lens of CHIWOS, examining psychosocial determinants, clinical aspects, mental health, sexual and reproductive health outcomes, and healthcare access and quality gaps to inform policy and programming for women with HIV in Canada. A recurring theme in the composite concept maps and summary diagrams was the lack of receipt of comprehensive women-centred HIV care3 including lack of discussion of reproductive goals, and access to care like gender affirmation. This finding suggests providers must improve knowledge through accessing clinical guidelines related to women with HIV such as the Canadian HIV Pregnancy Planning Guidelines, the Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in Adults and Adolescents with HIV, the British Columbia Guidelines for the Care of HIV Positive Pregnant Women and Interventions to Reduce Perinatal Transmission, and the Sherbourne’s Guidelines for Gender-Affirming Primary Care.25–28 The composite concept maps also demonstrate the negative effects of low socioeconomic status and stigma and discrimination on women’s self-reported resilience. This could impact the ability to self-advocate in healthcare settings, further affecting quality of care received. This finding has important implications to how clinicians and service providers approach care relationships and the importance of practicing from a person-centred lens.

In exploring the intricate layers of women’s experiences with HIV, composite concept maps 2, 3 and 4 show the profound impact stigma has on the lives of women with HIV. Societal stigma surrounding HIV not only amplifies the complexities of managing a chronic health condition, but also significantly contributes to heightened mental and emotional distress. Within this challenging context, resilience emerges as a pivotal force in composite concept maps 1 and 6. The intricate interplay between resilience and stigma reveals a dynamic process in which women not only navigate adversity but also actively contribute to dismantling societal prejudices.29 These maps contribute to a deeper understanding of the complex relationship between stigma, resilience and empowerment, which the Wheel of Resilience and the summary diagrams points to the need for a more supportive environment for women with HIV.

The interconnectedness between mental health and experiences of violence in adulthood further compounds the challenges women with HIV face, as depicted in composite concept maps 1–4. Women with HIV often contend with not only the physiological ramifications of the virus but also the psychological distress stemming from social stigma and potential encounters with violence. Composite concept map 3 highlights this especially for Indigenous women, who confront heightened violence in adulthood, likely due in part to the impact of historical and systemic factors such as colonialism and anti-Indigenous racism. While this trend was primarily noted among Indigenous women, it is probable that similar dynamics affect other racialised women as well. Composite concept map 2 introduces another dimension by revealing a correlation between experiencing violence in adulthood and a decrease in the utilisation and adherence to cART. This clinical impact of violence emphasises the pressing need for comprehensive trauma healing interventions. Evidently, the convergence of mental health, stigma and violence presents significant obstacles for women with HIV to access adequate mental health support, worsening existing disparities. It is vital to address this complex relationship to develop a more holistic approach to care for women with HIV, ensuring much-needed interventions are not only medically effective but also tailored to women’s unique health and holistic needs.

Another notable finding was the significance of positive healthy actions in the health experiences of women with HIV. This theme was evident in several composite concept maps, including map 1, which illustrated connections between social support and reduced HIV-related stigma, and map 2, which demonstrated correlations between peer leadership involvement and increased awareness of ART prevention benefits. This finding has substantial policy implications, suggesting that investment in peer leadership and support programmes for women with HIV can yield tangible mental and physical health benefits. Such proactive measures may contribute to a reduced burden on the greater healthcare system.

The next steps for policy advocacy are the co-development of a national women-centred HIV care30 strategy that ensures equitable access to care including gender affirmation, and resource creation and education to increase knowledge about the healthcare gaps women with HIV experience in Canada. Since the completion of this study, the field of women-centred HIV care has experienced significant developments, including the publication of a women-centred HIV care model informed by CHIWOS findings in 2021,30 the launch of new women-specific HIV studies such as the British Columbia CARMA-CHIWOS study,31 and movement towards a National Action Plan to advance the sexual and reproductive health and rights of women with HIV in Canada.32 Aligned with these recent contributions, the findings from this concept mapping study underscore persisting unanswered questions and emphasise crucial future research priorities. One essential research focus that arises from our study is the need to develop and implement comprehensive women-centred HIV care strategies in clinical settings to facilitate translation of women’s needs to their care providers, thereby influencing clinical measures of health and well-being. Moreover, our findings, coupled with insights from the broader literature3 22 33–38 highlight the diversity among women with HIV, reflecting the varied nature of their needs. While the women-centred HIV care model provides a solid foundation, it is evident that women’s priorities and needs vary, often shaped by other aspects of their identity including race and gender identity. Led by members of the respective groups and individuals with lived experience, ongoing efforts are being made to customise and tailor the women-centred HIV care model for priority populations, including trans women, African, Caribbean and Black women, as well as Indigenous women. Our findings also highlight the need to investigate the intersection of mental health, stigma, trauma and violence, and its impact on the well-being of women with HIV, as well as to develop trauma-informed strategies, approaches and programming aimed at addressing these intersecting factors. In summary, future research should concentrate on developing positive and health-oriented actions and programmes tailored to women with HIV, incorporating an intersectional perspective. These efforts should not only address the unique needs shaped by diverse aspects of identity, but also offer leadership and capacity-building opportunities for peer-led initiatives centred around self-care and well-being.

Conclusion

We developed a unifying summary of the health experience of women with HIV in Canada by applying concept mapping to 60 CHIWOS publications. The produced visuals can be used to inform policy and programming by providing easy to understand evidence on gaps related to the social determinants of health including housing, food security and income, in addition to structural barriers such as multiple areas of discrimination. Importantly, these visuals promote strength-based approaches to women with HIV’s health and well-being. The results of this study should guide future research and care priorities for women with HIV in Canada, placing a specific emphasis on trauma-informed, peer-led positive healthy actions accessible to women in all their diversity. This includes initiatives aimed at enhancing women-centred HIV care and self-care to comprehensively improve the holistic well-being of women with HIV.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all participants involved in this study. The authors would also like to thank LJ from The Public Studio for his collaboration in creating the two summary diagrams.

Footnotes

Twitter: @carmenlogie, @missmonaloutfy

Contributors: AY, PM, MK and MRL contributed to the study conception and design. AY, PM, MK and BG contributed to the preparation, participant recruitment and publication screening process. AY, PM, MK and MRL participated in the development of concept maps and summary diagrams. PM, JK and MRL wrote the first draft of the manuscript. VN, RG, PF, YP, NO, BG, BB, SS, MN, AF, RG, CC, KW, MS, AL-D, CHL, AdP, AK and ML provided feedback and edits on all the visuals and versions of the manuscripts. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. PM and MRL are guarantors for the work and conduct of the study.

Funding: The authors were financially supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), the CIHR Canadian HIV Trials Network (CTN 262). PM was supported through a CTN Postdoctoral Fellowship Award from the CIHR Canadian HIV Trials Network under Grant CTN 262 at the time of this study.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

No data are available.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

The study was assessed by the research ethics board at Women’s College Hospital to not require ethical approval by a human research ethics committee because the Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects did not apply. Instead, participants, all of whom had been previously engaged as CHIWOS research team members participated as research consultants to the concept process on a volunteer basis. We obtained informed consent from all participants in CHIWOS.

References

- 1. Loutfy M, de Pokomandy A, Kennedy VL, et al. Cohort profile: the Canadian HIV women’s sexual and reproductive health cohort study (CHIWOS). PLoS One 2017;12:e0184708. 10.1371/journal.pone.0184708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Loutfy M, Greene S, Kennedy VL, et al. Establishing the Canadian HIV women’s sexual and reproductive health cohort study (CHIWOS): operationalizing community-based research in a large national quantitative study. BMC Med Res Methodol 2016;16:101. 10.1186/s12874-016-0190-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. O’Brien N, Godard-Sebillotte C, Skerritt L, et al. Assessing gaps in comprehensive HIV care across a typology of care for women with HIV in Canada. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2020;29:1475–85. 10.1089/jwh.2019.8121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. USPHS (U.S. Public Health Service) . Report of the public health service task force on women's health issues. Public Health Reports 1985;100:73–106. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mastroianni AC, Faden R, Federman D. Women and health research: a report from the institute of medicine. Kennedy Inst Ethics J 1994;4:55–62. 10.1353/ken.0.0121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cargo M, Mercer SL. The value and challenges of participatory research: strengthening its practice. In: Annual Review of Public Health. 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, et al. Review of community-based research: assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. J Public Health Manag Pract 1998;4:10–24. 10.1097/00124784-199803000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kaida A, Carter A, Nicholson V, et al. Hiring, training, and supporting peer research associates: operationalizing community-based research principles within epidemiological studies by, with, and for women with HIV. Harm Reduct J 2019;16:47. 10.1186/s12954-019-0309-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Abelsohn K, Benoit AC, Conway T, et al. ‘Hear(Ing) new voices’: peer reflections from community-based survey development with women with HIV. Prog Community Health Partnersh 2015;9:561–9. 10.1353/cpr.2015.0079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. CHIWOS . The Canadian HIV women’s sexual and reproductive health cohort study [internet]. 2013. Available: http://www.chiwos.ca [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11. Novak JD, Gowin DB, Kahle JB. Learning How to Learn. Cambridge (UK): Cambridge University Press, Available: https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/identifier/9781139173469/type/book [Google Scholar]

- 12. Novak J. The importance of conceptual schemes for teaching science. The Science Teacher 1974;31:10–3. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Novak JD, Cañas AJ. The origins of the concept mapping tool and the continuing evolution of the tool. Information Visualization 2006;5:175–84. 10.1057/palgrave.ivs.9500126 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Daley BJ. Using concept maps in qualitative research. Paper presented at: the 1st international conference on concept. Pamplona, Spain, 2004:14–7. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bronfenbrenner U. The ecology of human development: experiments by nature and design. Massachusetts (USA): Harvard University Press, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 16. McLeroy KR, Bibeau D, Steckler A, et al. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Educ Q 1988;15:351–77. 10.1177/109019818801500401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dahlberg LL, Krug EG. Violence a global public health problem. Ciênc Saúde Coletiva 2006;11:277–92. 10.1590/S1413-81232006000200007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Novak J. As facilitative tools in schools and corporations. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 2006;3:77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cañas AJ, Hill G, Carff R, et al. CmapTools: a knowledge modeling and sharing environment. Paper presented at: the 1st International Conference on Concept. Pamplona, Spain, 2004:14–7. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lacombe-Duncan A, Berringer KR, Green J, et al. “I do the she and her”: a qualitative exploration of HIV care providers’ considerations of trans women in gender-specific HIV care. Womens Health (Lond) 2022;18:17455057221083809. 10.1177/17455057221083809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lacombe-Duncan A, Kia H, Logie CH, et al. A qualitative exploration of barriers to HIV prevention, treatment and support: perspectives of transgender women and service providers. Health Soc Care Community 2021;29:e33–46. 10.1111/hsc.13234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lacombe-Duncan A, Logie CH, Persad Y, et al. Implementation and evaluation of the ‘transgender education for affirmative and competent HIV and healthcare (TEACHH)’ provider education pilot. BMC Med Educ 2021;21:561:561. 10.1186/s12909-021-02991-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Skerritt L, Kaida A, Savoie É, et al. Factors and priorities influencing satisfaction with care among women with HIV in Canada: a fuzzy cognitive mapping study. J Pers Med 2022;12:1079. 10.3390/jpm12071079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Loutfy M, Kennedy VL, Poliquin V, et al. No. 354-Canadian HIV pregnancy planning guidelines. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2018;40:94–114. 10.1016/j.jogc.2017.06.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents . Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in adults and adolescents with HIV [Internet]. 2023. Available: https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/

- 27. Money D, Tulloch K, Boucoiran I, et al. British Columbia guidelines for the care of HIV positive pregnant women and interventions to reduce perinatal transmission. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rainbow Health Ontario: Sherbourne Health . 4th edition: sherbourne’s guidelines for gender-affirming primary care with trans and non-binary patients [Internet]. 2022. Available: https://www.rainbowhealthontario.ca/product/4th-edition-sherbournes-guidelines-for-gender-affirming-primary-care-with-trans-and-non-binary-patients/ [Accessed 04 Jul 2023].

- 29. Malama K, Logie CH, Sokolovic N, et al. Pathways from HIV-related stigma, racial discrimination, and gender discrimination to HIV treatment outcomes among women living with HIV in Canada: longitudinal cohort findings. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2023;94:116–23. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000003241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Loutfy M, Tharao W, Kazemi M, et al. Development of the Canadian women-centred HIV care model using the knowledge-to-action framework. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care 2021;20:2325958221995612. 10.1177/2325958221995612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Swann SA, Kaida A, Nicholson V, et al. British Columbia CARMA-CHIWOS Collaboration (BCC3): protocol for a community-collaborative cohort study examining healthy ageing with and for women living with HIV. BMJ Open 2021;11:e046558. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-046558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kaida A, Cameron B, Conway T, et al. Key recommendations for developing a national action plan to advance the sexual and reproductive health and rights of women living with HIV in Canada. Womens Health (Lond) 2022;18:17455057221090829. 10.1177/17455057221090829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Logie CH, James L, Tharao W, et al. HIV, gender, race, sexual orientation, and sex work: a qualitative study of intersectional stigma experienced by HIV-positive women in Ontario, Canada. PLoS Med 2011;8:e1001124. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Loutfy MR, Logie CH, Zhang Y, et al. Gender and ethnicity differences in HIV-related stigma experienced by people living with HIV in Ontario, Canada. PLoS One 2012;7:e48168. 10.1371/journal.pone.0048168. Available from. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mbuagbaw L, Husbands W, Baidoobonso S, et al. A cross-sectional investigation of HIV prevalence and risk factors among African, Caribbean and black people in Ontario: the A/C study. Can Commun Dis Rep 2022;48:429–37. 10.14745/ccdr.v48i10a03 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kronfli N, Lacombe-Duncan A, Wang Y, et al. Access and engagement in HIV care among a national cohort of women living with HIV in Canada. AIDS Care 2017;29:1235–42. 10.1080/09540121.2017.1338658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Logie CH, Kennedy VL, Tharao W, et al. Engagement in and continuity of HIV care among African and Caribbean black women living with HIV in Ontario, Canada. Int J STD AIDS 2017;28:969–74. 10.1177/0956462416683626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lacombe-Duncan A. An intersectional perspective on access to HIV-related healthcare for transgender women. Transgend Health 2016;1:137–41. 10.1089/trgh.2016.0018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2023-078833supp001.pdf (3MB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

No data are available.