Disfiguring and mutilating operations, especially of the face, breasts, genitals, and reproductive organs, often have a deleterious effect on a woman’s self image and sexuality. Sociopsychological aspects of body image form a complex pattern of self knowledge and how one is perceived by others. The invasion of surgery invariably causes temporary or permanent changes, which may not be anticipated by women or may emerge only on discharge from hospital.

Partners who adapt poorly to the new circumstances may also find it difficult to continue sexual activity, but an existing strong and intimate relationship encourages positive postoperative adjustment.

Dealing with psychological and emotional states such as anxiety, fear, and depression about surgery is crucial to a woman and her partner. Medical teams should encourage women to discuss their worries, especially sexual anxieties, as problems become more entrenched and more difficult to treat over time. Postoperative surveys of women suggest that 28-50% wanted their doctor to address sexual difficulties. Rehabilitation is important in promoting adjustment and acceptance by facilitating the grieving process.

Ileostomy, colostomy, and urostomy

Women who have a stoma as a result of chronic illness such as irritable bowel disorder, ulcerative colitis, and Crohn’s disease often experience a better psychological and sexual outcome than do those who undergo emergency surgery for, say, cancer of the colon. Healthy adaptation to a stoma depends on preoperative and postoperative counselling and understanding by stoma nurses. Patients’ greatest fears are loss of control, bad odour, noise, leaking or bursting bags, unsightliness, and their partner’s feelings towards them.

Factors affecting sexual function after an operation

Disfigurement or mutilation altering the body image

Previous psychological and emotional states

Physical pain and hormonal, vascular, or nervous damage

Existing problems with intimacy and quality of relationship

It can be some time before a couple resumes love making after surgery, particularly if attention is focused on the patient’s survival or if there are complications such as ill fitting appliances, parastomal sepsis, and skin excoriation. Dyspareunia can be a major problem, not only because of lack of arousal or secondary vaginismus after surgery but because of the amount of scar tissue within the pelvis.

Hip surgery

Total or partial hip replacement is now a common operation, but when a patient can safely resume sex is often not mentioned. Anatomically, internal rotation is dangerous postoperatively because it can lead to dislocation, but, as intercourse usually requires external rotation of the joint, sex can generally be resumed when the scar is comfortable.

Heart operations and angina

While these are often done as lifesaving operations with very good outcomes, women must be allowed to discuss their fears about when or if it is safe to restart sexual activity. Intercourse can take place when a woman feels like it, provided she can walk up two flights of stairs without difficulty, the equivalent cardiac output of orgasm. Angina may limit her activity, although this is unlikely. After a chest operation, she should take the female superior or another comfortable position until discomfort from the chest scar has eased.

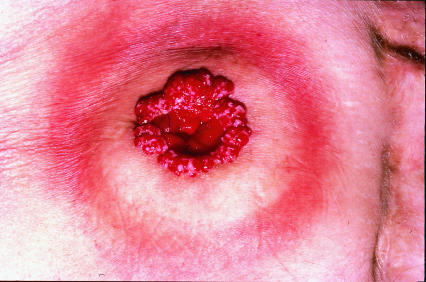

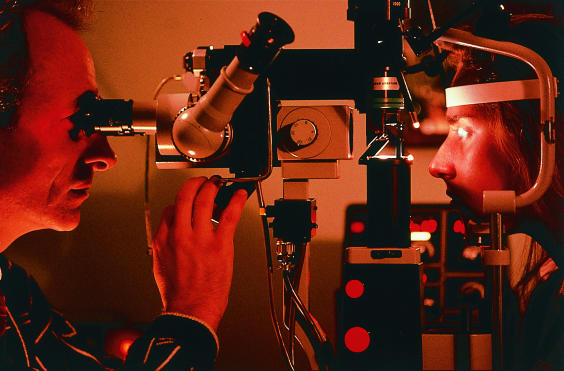

Eye operations

Cataract removal places no restrictions on sexual activity, but intercourse should be avoided for two weeks after a retinal detachment, and patients with vitreous haemorrhages need to wait until their laser treatment has finished or, if they do not have diabetes, two weeks after the bleeding has stopped.

Gynaecological operations

Hysterectomy

The uterus, menstruation, and fertility are seen by many women as fundamental to their femininity. After hysterectomy women often have great difficulty becoming sexually aroused, particularly when there are signs of depression before the operation and the woman is aged under 40. However, in some women, for whom other treatments have not worked, hysterectomy can be a relief from heavy bleeding, pain, and tiredness, allowing a freer sexual life.

Example of a case history: A 49 year old housewife of average intelligence came to a family planning clinic eight weeks after undergoing a hysterectomy because she was worried about not having had a period yet and to find out when she could resume sexual intercourse. She had not felt able to ask at the gynaecology clinic because everyone was so busy

Intercourse is usually allowed after six weeks, but this is somewhat arbitrary. Gentle penetration is quite possible after four weeks, although many women prefer to wait longer.

Vaginal repairs

These are done mainly for prolapse of the bladder or rectum. Some women complain of postoperative vaginal tightness or dyspareunia because of tender scar tissue. They should be encouraged to restart sexual intercourse when it feels comfortable, using a water based lubricant such as KY jelly or Senselle or an aromatic oil such as peach kernel or sweet almond oil (though oils must not be used with barrier contraceptives made from latex rubber as they may render them ineffective).

Incontinence and colloid injections

Sexual expression can be badly affected by incontinence, with fears about odour, leakage, and wetness. If a woman tenses her pubococcygeal muscles and bladder sphincter in order not to dribble urine, the resulting physiological and psychological tension can lead to vaginismus and possibly dyspareunia and interference with sexual arousal and orgasm.

Minor operations

The diagnosis of an abnormal cervical smear can create great anxiety, especially when it is totally unexpected. It is important to let a woman express her anxiety and fears about cervical cancer and its effect on her sex life before referring her for colposcopy. She will then find it easier to resume her sexual life after treatment.

Female genital mutilation

This operation is illegal in Britain, but the obstetric and sexual sequelae are seen in clinics in areas with large African and Middle Eastern communities. Recent arrivals may need deinfibulation because they are getting married or are pregnant. Young women brought up in Britain may feel mutilated compared with their peers. They need appropriate sexual counselling, and occasionally deinfibulation. Problems with non-consummation of marriage are common, often due to vaginismus. It is important that these women are examined by doctors comfortable with treating psychosexual problems.

Episiotomies, obstetric tears, and trauma

Episiotomies are routinely done to prevent tears in the perineum during labour. It is essential that midwives and junior doctors are properly trained and take great care in the site and length of incision and its repair to protect the perineum. Poor repairs that lead to painful scars, malposition of the sutures, narrowing of the introitus, or even extrusion of pieces of catgut can severely affect sexual pleasure.

Since low sexual desire, dyspareunia, and secondary vaginismus are common responses after childbirth, women may benefit from postnatal referral to a therapist to discuss sexual dysfunction. Psychological reasons are varied, but tiredness, especially when breast feeding, and fears of a further pregnancy can have a negative effect on a sexual relationship. A woman’s focus on her body as a mother rather than as a lover can also affect sexual function.

Termination of pregnancy

Some women feel relieved after a termination, and it has little impact on their psychological wellbeing, but others may feel a deep sense of loss and grief. This causes anxiety, depression, loss of sexual desire, and difficulties within an existing relationship. When this happens, the reasons why the termination was wanted need to be explored, and all the emotions of that loss need to be counselled. Intercourse can be resumed when the woman has stopped bleeding after the termination if she feels like it.

Possible negative experiences after termination of pregnancy

Avoidance, denial, feelings of numbness or worthlessness

Anger, tearfulness, depression

Dissociation from body, negative thoughts and feelings

Recurrent intrusive thoughts, flashbacks, dreams and nightmares

Guilt, shame, detachment, loss of positive feelings

Suicidal thoughts, feelings of loss of control

Psychological problems (eating disorders, etc)

Disinterest in and avoidance of sex, possible vaginismus

Symptoms can be immediate, delayed, or chronic

Sterilisation

Women aged over 30 who have completed their family, and especially those who have had problems with contraception, may find that their sexual activity improves after elimination of the possibility of unwanted pregnancies, and they can resume intercourse as soon as they feel physically comfortable after the operation. On the other hand, women coerced into unwanted sterilisation may retreat sexually.

Operations for infertility

The pressure to perform to a calendar gives rise to many sexual problems for both men and women. The low success rate of treatments also increases the feelings of failure, loss, grief, frustration, and depression. Couples need counselling to maintain their sexual intimacy while undergoing medical and surgical interventions and beyond.

Operations for cancer

Operations such as hysterectomy, bilateral oophorectomy, and radical vulvectomy can cause major genital mutilation, often producing difficult psychosexual problems. Women have to deal not only with the fear and anxiety of the diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis but with the constant fear of recurrence. They often do not know what to expect sexually after an operation because of lack of communication with their doctors as well as with their partners.

Minimising psychosexual problems after gynaecological operations for cancer

Try to involve the partner

Avoid radiotherapy if possible

Minimise physical mutilation

Preserve ovarian function

Reconstruct vagina if possible

At follow ups check sexual activity

Refer for sexual counselling

Partners mainly suffer in silence and find it difficult to make sexual approaches. They fear being seen as selfish or not understanding the physical and emotional pain that the woman is going through, or they may put more pressure on her by assuming that she wants sex. Some partners find that they cannot cope with the physical differences caused by the operation, and this makes restarting a sexual life a big ordeal.

A recent study showed that 75% of women who had undergone radical vulvectomy or radical hysterectomy had sexual difficulties for more than six months postoperatively, and 15% never resumed sexual intercourse. Women who were aged under 50 or not sexually experienced and those not in a relationship at the time of the operation were worst affected. The most common problem was lack of sexual arousal.

Discussing the implications of a gynaecological operation

Explain possible risks to sexuality

Allow expression of fears, myths, gains, and losses

Facilitate communication between partners

Help to increase intimacy

Genital sex is not the only form of sex

Explore other forms of sex and intimacy

Offer appropriate support

A frank preoperative discussion is essential, and the women’s partner should be involved from the beginning. If at all possible, radiotherapy should be avoided in order to minimise the physical mutilation and to preserve the ovaries. At every follow up visit all women should be asked how their sexual life is progressing, and sexual counselling should be offered early to minimise long term damage.

Discussion and management

Before an operation takes place it is essential to discuss with the woman, and preferably with her partner, the full implications of the operation on their sexual life. To allow the full expression of their fears, myths, gains, and losses, discussions should be conducted in private in a frank and empathic way. This helps to minimise sexual dysfunction after the operation.

Postoperatively, permission giving and the importance of starting sexual activity early should be emphasised. If a woman has had radiotherapy, oestrogen cream should be used in the vagina. Different positions for intercourse may have to be tried to lessen dyspareunia. Clinical depression should be treated first. When there are intrinsic difficulties with a relationship, the couple should be counselled by an appropriately trained person.

Further reading

Crowther ME, Corney RH, Shepherd JH. Psychosexual implications of gynaecological cancer. BMJ 1994;308:869-70.

Help with sexual problems

A list of clinics and practitioners is available from the British Association for Sexual and Marital Therapy, PO Box 13686, London SW20 9ZH

Before surgery, some couples may have chosen not to be sexually active, and this must be taken into account when discussing sexual activity before and after the operation. Good communication skills, especially good listening skills, are essential if a doctor is to show empathy, respect, and non-judgmental attitudes when discussing sexual issues with patients.

Figure.

Disfiguring operations, especially of the face and sexual organs, often have a deleterious effect on a woman’s self image and sexuality. (Detail from On Surgery (14th century manuscript) by Rogier de Salerne)

Figure.

Healthy adaptation to a stoma depends on adequate counselling for both the patient and her partner

Figure.

Patients undergoing laser treatment for a detached retina or vitreous haemorrhage should be warned to avoid sexual activity

Figure.

African girl undergoing ritual circumcision (photographed with subjects’ permission)

Figure.

Examination of a woman who had undergone ritual genital mutilation as a child and who now requires deinfibulation to enable her to reproduce

Figure.

Exploration of a six month old episiotomy scar to remove a painful granuloma, probably the result of stitch that was not removed after the original procedure

Figure.

Removal of a woman’s uterus and ovaries because of cervical or uterine cancer can lead to psychosexual problems in addition to the fear of the diagnosis and treatment

Figure.

After an operation, different positions for intercourse may have to be tried to lessen dyspareunia. (Man and woman making love, from Love (1911) by Mihaly von Zichy)

Acknowledgments

The manuscript by Salerne and the engraving by Zichy were reproduced with permission of the Bridgeman Art Library. The photographs of a stoma, of eye surgery (by Phillip Hayson), of female genital mutilation (by James Stevenson), of granuloma in an episiotomy scar (by P Marazzi), and of hysterectomy (by Antonia Reeve) were reproduced with permission of Science Photo Library. The photograph of a girl undergoing ritual circumcision was reproduced with permission of Carol Beckwith and Angela Fisher.

Footnotes

Asun de Marquiegui is a sex therapist and instructing doctor in family planning in London, and Margot Huish is a sex and relationship therapist in Barnet Healthcare NHS Trust, Barnet Hospital, and in private practice.

The ABC of sexual health is edited by John Tomlinson, physician at the Men’s Health Clinic, Winchester and London Bridge Hospital, and formerly general practitioner in Alton and honorary senior lecturer in primary care at University of Southampton.