Abstract

We investigate the impacts of a perinatal psychosocial intervention on trajectories of maternal mental health and child skills, from birth to age 3. We find improved maternal mental health and functioning (0.17 to 0.29 SD), modest but imprecisely estimated improvements in parenting (0.07 to 0.11 SD), and transitory improvements in child socioemotional development (0.06 to 0.39 SD). The intervention had negligible influence on physical health and cognition. Estimates of a skill production function reveal the intervention attenuated the negative association between maternal depression and child outcomes, and narrowed outcome gaps between mothers who were and were not depressed in pregnancy.

Keywords: Mental health, stress, socioemotional, RCT, child development, technology of skill formation, gender

1. Introduction

Social and emotional skills are an integral component of human capital. Children living in disadvantaged families, with mothers more likely to be suffering from poor mental health or depression, tend to show greater socioemotional difficulties (Rahman et al., 2013; Hollins, 2007; Bennett et al., 2016; Halfon et al., 2014; Attanasio et al., 2022a). Socioemotional difficulties become apparent early in life, and are prone to get ingrained and intensify over time, in a cascading cycle of disadvantage (Feil et al., 1995; Sprague and Walker, 2000).1 For instance, there is some evidence that socioemotional problems at ages 1–3 predict socioemotional difficulties in elementary school (Briggs-Gowan and Carter, 2008), which in turn reduce school performance (Fletcher, 2010; Ding et al., 2009; Busch et al., 2014; Bhalotra et al., 2021) and predict mental health issues in early adulthood (Class et al., 2019; National Scientific Council on the Developing Child, 2012). Despite these patterns, causal evidence of the consequences of maternal depression, or its treatment, for child socioemotional skills is relatively scarce.

In this paper, we analyze the impact of a perinatal psychosocial intervention targeted at depressed mothers on the joint evolution of maternal mental health and functioning, parental investment, and child skills from birth through to three years of age. The skills that we analyse encompass not only socioemotional, but also cognitive skills and physical health. This inclusion is important as these skills tend to evolve jointly. Our focus is on the mother since she is the primary caregiver in our setting and, in general, the child interacts with her more than with anyone else. As a result, her mental health and functioning have a potentially strong influence on the child. Depression and stress often manifest in low energy, impaired functionality, insomnia, poor concentration, pessimism, and a lack of interest in one’s environment (de Quidt and Haushofer, 2018). It is thus plausible that depression modifies the mother’s parenting behaviors and investment in the child (Herba et al., 2016; Baranov et al., 2020; Angelucci and Bennett, 2021). A rich literature in developmental psychology posits that improving maternal depression can lead to more responsive mother-child interactions and support secure infant attachment (Erickson et al., 2019; Tsivos et al., 2015).

The intervention we study, the Thinking Healthy Programme - Peer Delivered (THPP), was targeted at perinatally depressed women in rural Pakistan. So as to improve scalability, it was delivered by trained peer-volunteers through a combination of home visits and group sessions. In total, between the third trimester of pregnancy and the child turning 3 years of age, a mother in the program received 32 sessions. The intervention provided cognitive behavioral therapy with a focus on behavioral activation, self-care, and the child’s health and development. Thus the content of the program was such that it could influence child outcomes directly, or through modifying the mother’s mental health and her parenting behaviors.

Rich longitudinal data on mother-child pairs were collected in multiple waves throughout the intervention period. Socioemotional skills are measured using the Ages and Stages Questionnaire-Social-Emotional (ASQ-SE) which contains validated psychometric indices of competencies in self-regulation, adaptive functioning, emotional balance, communication, and prosociality. Cognitive skills are tested using the Bayley Scales of Infant Development (Bayley-III) which includes cognitive, language, and motor skills. Maternal mental health and functioning are assessed using established scales for measurement of depression (a clinical assessment and symptom severity), stress, and functional disability. Parental investment in children is measured using the HOME score, assessing the quality of cognitive stimulation and emotional support in the household.

In order to link the observed variables in the dataset to the underlying developmental trajectories of children, we use a latent variable approach, common in psychometrics and economics (Spearman, 1904; Jöreskog and Goldberger, 1975; Carneiro et al., 2003). We generate factor scores and use these to estimate treatment effects on six indicators: cognition, physical development, and socioemotional skills of the child; parental investment; maternal mental health, and maternal functioning. The reduced form treatment effects tell us how the intervention modified inputs to child development (note that child skills at a younger age are inputs to child skills at an older age). So as to synthesize these reduced-form results, and describe how the intervention modified the returns to the inputs, we estimatethe production functions for child skills in the first three years of life, using as a point of departure, the formulation in Cunha and Heckman (2008); Attanasio et al. (2020c).

We make two main contributions. First, we identify the impact of the intervention on trajectories of maternal mental health, parenting, and child development. In contrast to much of the literature, we use longitudinal data on children from birth to age 3, and we allow intervention impacts to vary with age, identified at 6, 12, and 36 months after birth.2 We find that the intervention improves maternal mental health (ranging from 0.17 to 0.27 standard deviations, SD) and daily functioning (0.18 – 0.29 SD) immediately (at 6 months) and persistently up until the end of the study window, 36 months after birth. The intervention results in weakly identified increases in parental investment at 12 and 36 months (0.07 – 0.11 SD), and a short-term positive effect on the child’s socioemotional skills at 6 and 12 months (0.19 – 0.39 SD), without any discernible impacts on the other domains of child development (physical health impacts ranged from −0.17 to 0.02 SD and cognitive development impacts ranged from −0.08 to 0.06 SD). All of these results are stronger for mothers of boys.

Our second contribution is to estimate a model of child skill formation in which, in a departure from related studies (Cunha and Heckman, 2008; Cunha et al., 2010; Attanasio et al., 2020a), we include dynamic latent factors measuring maternal mental health (including depression and stress) and functioning. We conceptualize maternal mental health as a capital input in the production function, a stock that can depreciate over time or that can be invested in, for instance with therapy.

Similar to other studies estimating the child skills production function, we do not have multiple instruments and we cannot identify causal effects of (endogenous) inputs. However, we allow the model parameters to vary by treatment arm. The model allows the intervention to influence both the levels and the productivity of the inputs, similar in spirit to Kitagawa (1955); Oaxaca (1973); Blinder (1973).

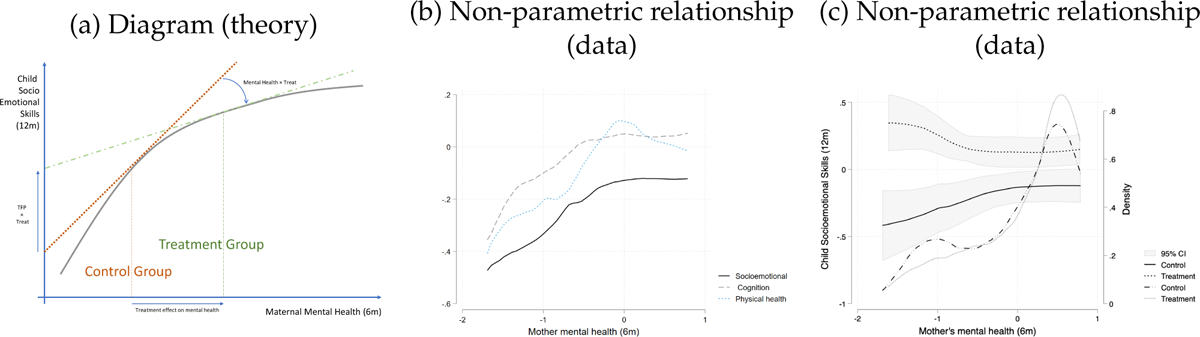

Our findings suggest that maternal mental health is an important input in the technology of skill formation, especially for moderately or severely depressed mothers, and that the intervention changes the shape of the production function, especially in the first year of life. In the control group, all child skills are increasing in maternal mental health, but at a decreasing rate. We see a larger improvement in children’s skills when moving from severe to moderate depression than we do when moving from moderate to mild depression. The intervention shifts the production function up (an increase in TFP), and also attenuates the slope of the production function with respect to maternal mental health, leading to improvements in skills particularly for children whose mothers did not recover from depression.3 The intervention modifies the production function parameters in a manner that brings outcomes for treated mothers closer to outcomes for mothers who were not depressed at baseline.

These findings help reconcile the pattern of results identified in the reduced form models of intervention effects, namely, the absence of durable effects of the intervention on child skills alongside long-lasting improvements in maternal mental health. The intervention helps women recover from depression and stress, and it also improves children’s socioemotional skills in the short run. We might have surmised from this evidence that the improvement in maternal mental health at 6 and 12 months was the cause of the improvement in socioemotional skills at 12 months. However the production function estimates suggest this is not the case, as the intervention improves child socioemotional skills particularly in the sample of mothers who do not recover from depression. This is consistent with the fact that the intervention did not just provide therapy for the mother’s depression, it also provided information and support for child development. Our estimates indicate that the latter shielded children from the negative consequences of poor maternal mental health. As time progresses, additional increases in the stock of maternal mental health shift the treated group into a flatter part of the production function, where variation in the underlying measure of mental health is less predictive of child skills. Thus it makes sense that, although on average maternal mental health in the treated group remained persistently better than in the control group, other aspects of the intervention enabled the control group children to catch up with the treated children, resulting in convergence by 36 months in their (socioemotional) skills. The production function estimates also contribute to still scarce evidence on self- and cross-productivity of skills across domains at very early ages.

Understanding how maternal depression at birth may influence the formation of skills in the early years is important given the high prevalence of maternal depression: it is estimated that between 10 and 30 percent of children worldwide are exposed to maternal depression at birth, and that this share is higher in developing countries (O’hara and Swain, 1996; Parsons et al., 2012). Maternal depression is often undiagnosed and untreated, and between a third and a half of all women who are depressed during pregnancy remain depressed a year later, which implies a significant duration of exposure for many children.

Our finding that maternal mental health (in the control group of women diagnosed as clinically depressed at baseline, and not treated) is linked to the child’s socioemotional development has important consequences. A number of studies have documented that socioemotional skills in childhood are predictive of adult outcomes including mental health, educational attainment, and earnings (Currie and Stabile, 2006; Bennett et al., 2016; Halfon et al., 2014). Another strand of the literature demonstrates that socioemotional skills have an even longer-lasting impact, influencing the next generation.

In particular, a number of studies show a positive intergenerational correlation in socioemotional skills (Loehlin, 2005; Groves, 2005; Anger, 2012; Dohmen et al., 2012; Grönqvist et al., 2017; Attanasio et al., 2022a). Most of the cited studies measure socioemotional outcomes in adolescence or adulthood. One study that, like us, measures socioemotional outcomes in childhood is Attanasio et al. (2022a). However, they associate the child’s outcome with the mother’s socioemotional skills when she was a child, whereas we are primarily interested in the mother’s socioemotional skills when she is parenting the newborn child. A second difference in our study from the cited literature is that it is set in a developing country, and we know much less about socioemotional developmental paths in these settings. Third, none of the cited studies uses experimental variation in the mother’s socioemotional skills.

The paper is laid out as follows. Section 2 provides the details of the intervention, discusses baseline balance and attrition over time, describes the data set and the outcomes, and discusses the methodology used to reduce the dimensionality of the outcome space and estimate the treatment effects; Section 4 presents the empirical results; Section 5 discusses the mechanisms through the lens of a simple structural model; and Section 6 concludes.

2. Study Design and Data

2.1. The Intervention

We use longitudinal data on a pregnancy cohort, established in the context of a clustered Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT) in rural Punjab, Pakistan, a low-resource context characterized by a high prevalence of maternal depression and limited access to clinical mental health care. The trial recruited women who were depressed during pregnancy and provided them with a 3-year-long, peer-delivered psychosocial intervention (Thinking Healthy Programme Peer-Delivered Plus, THPP+) consisting of cognitive behavioral therapy with a focus on behavioral activation, self-care, and attention to the infant’s health and development.

Depression Screening.

Between October 2014 and February 2016, all pregnant women who were eligible for the study—married, resident in Kallar Syedan, a subdistrict of Rawalpindi in Pakistan, and not in need of immediate medical attention, were approached and screened for depression using the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). The PHQ-9 is a standard instrument for screening and monitoring the severity of depression; it includes questions about the frequency of depressive symptoms in the last two weeks, such as lack of interest or ability to concentrate, feelings of sadness or hopelessness, sleeping or eating problems, restlessness, suicidal thoughts. Pregnant women who scored 10 or more on the PHQ-9 were invited to participate in the trial.

Among 1731 women who were screened for depression, 572 (33%) were identified as depressed according to the PHQ-9 criteria. 287 of these mothers were in the clusters randomized to the intervention, 283 in the control clusters, and two mothers refused to participate before the baseline assessment. Of the 1159 pregnant women who were screened as not depressed, 584 were randomly selected to constitute the non-depressed arm of the study. They represent a natural reference group to understand the evolution of maternal and child outcomes, and to benchmark the potential effectiveness of the intervention.

Randomization.

The trial was randomized across 40 village clusters. These clusters were geographically separate to minimize the risk of spillover. Twenty clusters were randomized into receiving the intervention and twenty to the control arm. Each village cluster contributed approximately 14 perinatally depressed women. Research teams responsible for identifying, obtaining consent, allocating, and interviewing study participants were blind to the participants’ original depression status and their allocation across the study arms.

THPP+ Intervention.

Thinking Healthy Programme Peer-Delivered Plus (THPP+) is a low-intensity scaleable psychosocial intervention delivered by volunteer peer women from the same community as the mother. Peers received prior classroom training in accordance with the intervention content, which builds on a previous intervention that proved very successful in a similar context (Rahman et al., 2008). They were provided supervision throughout the trial period. The intervention strategy includes behavioral activation to overcome unhealthy thinking with a focus on self-care and infant development.

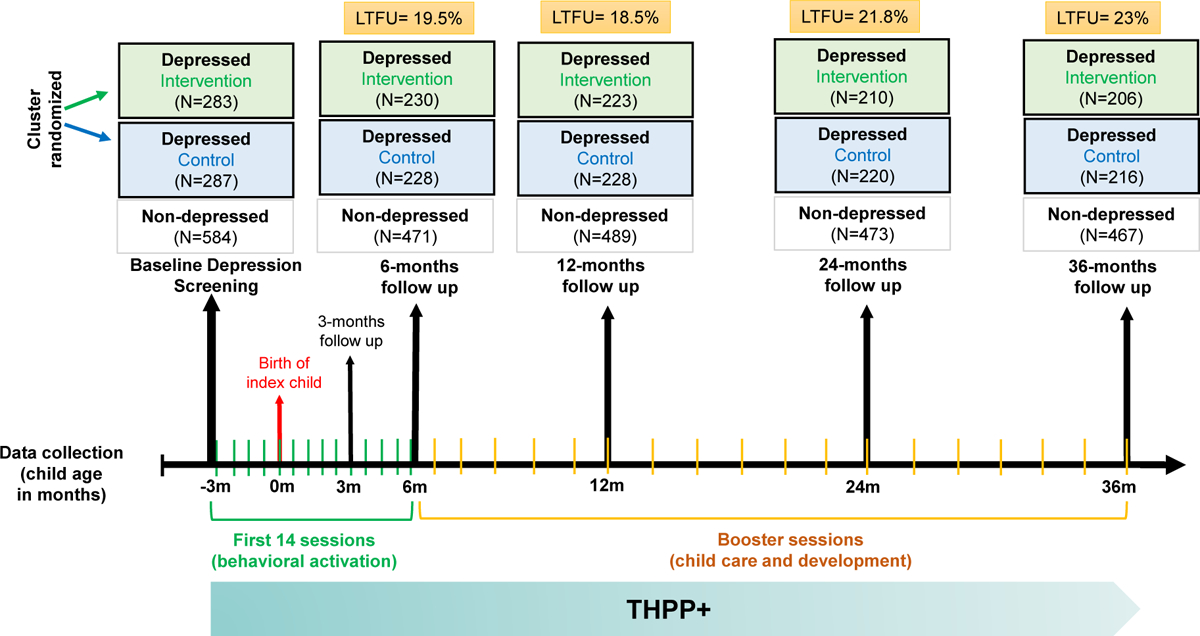

The timeline of the THPP+ intervention and all follow-up surveys is summarized in Figure 1. In the intervention group, depressed women received a combination of individual and group sessions. Starting from the third trimester of pregnancy until 6 months postpartum, participants attended ten individual and four group-based sessions, with a primary focus on modifying maladaptive thoughts and behaviors frequently observed among individuals experiencing depression. From 7 to 36 months postnatal, another 18 group sessions were delivered: the first six sessions were delivered monthly, the rest every two months. The content of these lower-intensity booster sessions was a continuation of the behavioral activation strategy with a special focus on contributing to the mother-child interaction and child development by providing examples of age-appropriate activities as well as information about childcare. Since a large part of the intervention was delivered in group sessions, the social component of meeting with other mothers, alongside the behavioural activation content discussed during the sessions, might have contributed to any intervention effects.

Figure 1:

Timeline of THPP+ Intervention and Follow-ups

Perinatally depressed women in the treatment arm received the THPP+ intervention throughout the trial, while women in the control arm received Enhanced Usual Care (EUC). EUC is the routine health care provided in the region. It is enhanced in the sense that the participants were informed of their depression status and offered guidance about how to seek help. Women who were not diagnosed as perinatally depressed (non-depressed group) did not receive any treatment.4

Sample and longitudinal follow up.

Our study sample consists of the experimental group of depressed mothers who were randomized into treatment and control arms, and the group of mothers who were not depressed at baseline. Data collection on the mother-child dyads was done six times: at the third trimester of pregnancy and 3, 6, 12, 24, and 36 months postpartum. Figure 1 provides the compositions of the follow-up samples and the respective loss-to-follow-up rates (LTFU). A longitudinal comparison requires a similar measurement system over time, but we have no measure of cognition at 3, 6, and 24 months and we have a different measure of parental investment at 24 months (see Table A1). For consistency, we only analyse data from the waves at 6, 12, and 36 months.5

2.2. Measurement and Outcomes

The data contain multiple validated and widely used scales of maternal mental health and functioning, and of the cognition, socioemotional, and physical health of children. A full list of measures is provided in Table A1 in the Appendix.

To measure maternal mental health across all of the waves, we use the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) and the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM (SCID), a 13-item semi-structured interview for making the major DSM-5 diagnoses. We also include the Cohen Perceived Stress Scale (PSS), a 10-item instrument among the most widely used in the psychological literature to measure self-reported stress. To measure her functioning, we use the WHO Disability Assessment Schedule (WHO-DAS), a 17-item assessment instrument developed by the World Health Organization (WHO) to evaluate across cultures and domains a person’s ability to perform various activities of daily living.

To assess the child’s cognitive development at 12 and 36 months of age, we use five scales from the Bayley Scales of Infant Development (Bayley-III). These scales measure various aspects of infant and toddler development in the following domains: Cognitive, Language (Receptive and Expressive), and Motor (Gross and Fine).

To measure the child’s socioemotional skills we use the social-emotional sub-scale of the Ages and Stages Questionnaire: (ASQ-SE), a validated screening tool for assessing social-emotional development in children aged 1 month to 6 years (Lamsal et al., 2018).6 The ASQ-SE uses parent-reported questions to identify potential difficulties or delays in the areas of self-regulation, compliance, communication, adaptive functioning, autonomy, interaction with people, and affect (the child’s ability or willingness to demonstrate their own feelings and empathy for others). At age 36 months we also include the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ), a brief behavioral screening questionnaire used to assess children’s mental health. It has sub-scales to detect emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity and inattention, peer relationship problems, and prosocial behaviour.

The child’s physical health was assessed by measuring their weight, height, and head circumference from 3 to 36 months. These measurements were converted to age-adjusted Z-scores, serving as proxies for the child’s anthropometrics and indicating their physical growth and development.

To measure parental investment at 12 and 36 months we used the HOME inventory, a well-established observational tool that evaluates the quality of cognitive stimulation and emotional support offered by parents to their child. It is a widely used measure to examine the level of parental investment in a child’s development.

Given the richness of the data for both mothers and children, we aggregate outcomes into indices to overcome measurement error problems, improve statistical power, reduce the dimensionality of the data, and mitigate the issue of multiple hypothesis testing. We present the main results using latent factor scores, described below, although patterns are similar using Inverse Covariance Weighted (ICW) indices.7

2.3. Balance and Attrition

Balance:

The experimental sample was slightly imbalanced at baseline, as shown by the summary statistics in Table 1. For instance, pregnant women in the treatment arm were on average 1 cm taller and lived in households with 0.3 more people per room than women in the control clusters. Treated women also suffered from slightly—albeit not significantly—worse mental health, scoring 0.4 higher on the PHQ-9 (depression), 0.6 on the WHODAS (functioning), and 0.9 on the PSS (stress). A joint F-test rejects balance of baseline characteristics (p-value=0.01).8 Splitting by gender of the index child shows that the sample of mothers of boys is more balanced than that of girls: treated mothers of girls scored 1.6 higher on the PSS, had 0.5 higher number of people per room, lower socio-economic status, and less educated husbands (Table A8). However, a joint test of balance for covariates within each gender group does not indicate any statistically significant imbalance, possibly due to lower statistical power (p-values of 0.41 for mothers of boys and 0.12 for mothers of girls).

Table 1:

Baseline Balance

| Baseline Sample (N=1154) | 6-months (N=929) |

12-months (N=940) |

24-months (N=903) |

36-months (N=889) |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Treatment | Nondep. | Diff. | p-val | Diff. | Diff. | p-val | Diff. | p-val | Diff. | p-val | Diff. | ||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | Mean | (ND-D) | (T-C) | p-val | (T-C) | (T-C) | (T-C) | (T-C) | p-val | |||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) | (12) | (13) | (14) | (15) | (16) | |

| Mother’s Age | 27.289 | 4.973 | 26.802 | 26.373 | −0.674 | 0.023 | −0.487 | 0.260 | −0.595 | 0.215 | −0.361 | 0.434 | −0.310 | 0.510 | −0.314 | 0.478 |

| Mother’s height (cm) | 156.330 | 6.088 | 157.429 | 157.105 | 0.230 | 0.545 | 1.100 | 0.074 | 0.996 | 0.145 | 1.043 | 0.109 | 1.352 | 0.031 | 1.023 | 0.131 |

| Mother’s weight (kg) | 61.241 | 12.883 | 60.172 | 59.887 | −0.823 | 0.186 | −1.070 | 0.359 | −1.205 | 0.325 | −0.861 | 0.476 | −1.065 | 0.432 | −1.286 | 0.385 |

| Mother’s waist circ. (in) | 37.555 | 4.088 | 36.852 | 37.134 | −0.071 | 0.746 | −0.704 | 0.115 | −0.793 | 0.068 | −0.628 | 0.421 | −0.843 | 0.075 | −0.688 | 0.176 |

| Mother’s blood pressure | 72.326 | 12.790 | 70.915 | 71.667 | 0.043 | 0.950 | −1.411 | 0.173 | −0.352 | 0.723 | −1.169 | 0.263 | −0.339 | 0.748 | −1.049 | 0.308 |

| PHQ total | 14.484 | 3.580 | 14.894 | 2.796 | −11.891 | 0.000 | 0.410 | 0.248 | 0.400 | 0.305 | 0.484 | 0.227 | 0.364 | 0.362 | 0.380 | 0.347 |

| WHODAS total | 16.111 | 9.119 | 16.714 | 5.613 | −10.798 | 0.000 | 0.602 | 0.475 | 0.600 | 0.513 | 0.814 | 0.376 | 0.999 | 0.291 | 0.809 | 0.423 |

| PSS total | 22.899 | 7.523 | 23.841 | 12.212 | −11.154 | 0.000 | 0.942 | 0.100 | 1.311 | 0.036 | 1.113 | 0.072 | 1.216 | 0.062 | 1.020 | 0.151 |

| Current Major Dep. Episode | 0.732 | 0.444 | 0.777 | 0.021 | −0.734 | 0.000 | 0.046 | 0.373 | 0.055 | 0.359 | 0.039 | 0.509 | 0.044 | 0.461 | 0.045 | 0.443 |

| Joint/extended family | 0.634 | 0.483 | 0.580 | 0.707 | 0.100 | 0.000 | −0.055 | 0.175 | −0.058 | 0.228 | −0.049 | 0.321 | −0.060 | 0.206 | −0.075 | 0.096 |

| Grandmother present | 0.666 | 0.473 | 0.629 | 0.717 | 0.070 | 0.005 | −0.037 | 0.331 | −0.028 | 0.504 | −0.029 | 0.473 | −0.043 | 0.329 | −0.034 | 0.434 |

| Total adults in the hh | 5.700 | 2.993 | 5.332 | 5.985 | 0.467 | 0.011 | −0.368 | 0.201 | −0.320 | 0.334 | −0.325 | 0.316 | −0.212 | 0.527 | −0.281 | 0.402 |

| People per room | 2.473 | 1.870 | 2.792 | 2.215 | −0.416 | 0.001 | 0.319 | 0.087 | 0.325 | 0.078 | 0.348 | 0.056 | 0.322 | 0.066 | 0.316 | 0.097 |

| Number of girls | 0.854 | 1.064 | 0.958 | 0.663 | −0.243 | 0.000 | 0.104 | 0.328 | 0.071 | 0.120 | 0.090 | 0.433 | 0.124 | 0.308 | 0.051 | 0.655 |

| Number of boys | 0.787 | 0.961 | 0.855 | 0.560 | −0.261 | 0.000 | 0.068 | 0.443 | 0.002 | 0.987 | 0.023 | 0.817 | 0.037 | 0.705 | 0.039 | 0.700 |

| First child | 0.251 | 0.434 | 0.230 | 0.363 | 0.123 | 0.000 | −0.021 | 0.506 | −0.002 | 0.951 | 0.005 | 0.869 | −0.012 | 0.709 | −0.023 | 0.468 |

| SES asset index | −0.320 | 1.688 | −0.560 | 0.422 | 0.861 | 0.000 | −0.240 | 0.152 | −0.133 | 0.201 | −0.130 | 0.489 | −0.161 | 0.398 | −0.169 | 0.359 |

| Mother’s education | 6.801 | 4.546 | 6.827 | 8.567 | 1.753 | 0.000 | 0.025 | 0.957 | 0.376 | 0.428 | 0.311 | 0.537 | 0.087 | 0.863 | 0.096 | 0.849 |

| Father’s education | 8.331 | 3.288 | 7.848 | 9.151 | 1.059 | 0.000 | −0.483 | 0.134 | −0.560 | 0.117 | −0.609 | 0.102 | −0.844 | 0.026 | −0.750 | 0.037 |

| Life Events Checklist | 4.098 | 2.335 | 4.696 | 2.896 | −1.499 | 0.000 | 0.599 | 0.003 | 0.673 | 0.001 | 0.599 | 0.003 | 0.648 | 0.001 | 0.590 | 0.003 |

| Observations | 287 | 283 | 584 | |||||||||||||

| Joint test (p-value) | 0.011 | 0.028 | 0.053 | 0.018 | 0.141 | |||||||||||

Note: Table tests for balance of baseline characteristics. Columns 1, 3, and 4 show the mean in the control, treatment, and nondepressed group in the baseline sample, respectively. Column 5 shows the difference in means between non-depressed and depressed groups. Columns 7, 9, 11, 13, and 15 show the mean differences between treatment and control groups in the baseline sample and 6 months, 12 months, 24 months, and 36 months follow-up samples, respectively. p-values at the bottom of the table come from the F-test of overall significance from a regression of the treatment dummy on all the baseline controls.

Overall, this slight imbalance seems to be driven by small differences in participants’ baseline characteristics, not by systematic differences between treatment and control village-clusters. We confirm balance across village-clusters by using the mothers who were not depressed at baseline and lived in the same villages as treated and control mothers (Table A9). A joint test of balance using the baseline characteristics of mothers who were not depressed in pregnancy (baseline) shows balance across treatment and control clusters (p-value 0.456). Similarly, a joint test of balance using the whole sample (non-depressed and depressed mothers pooled) is not rejected. (p-value=0.317).

Attrition:

Lost to follow-up (LTFU) rates range between 18.5%−23% in the study period, and it is balanced across study arms. These attrition rates compare favorably with attrition rates in pregnancy cohort data. The main reason for being lost to follow-up was the death of the index child (constituting around 40% of the attritors),9 which was also balanced across study arms. We find some small imbalance in attritor characteristics (Tables A2–A5), but these differences are not statistically significant.10 Attritors generally had more crowded households and higher baseline PHQ-9 total scores. Attritors at 6 months additionally differ by having higher blood pressure and lower socio-economic status, and were more likely to be pregnant for the first time. Mothers who were lost to 36-month follow-up had higher weight and were more likely to co-reside with their mother or mother-in-law.

In the analysis to follow, we address baseline balance concerns by including covariates in the model, demeaned and interacted with the treatment indicator (Goldsmith-Pinkham et al., 2022). Although attrition is not differential by treatment status, we show that our estimates are robust to using inverse probability weights to adjust for attrition.

3. Analytical Framework

To study the impact of THPP+ on the developmental trajectory of maternal mental health and child skills, we use latent factor scores, following a long history in psychometrics (Spearman, 1904; Jöreskog and Goldberger, 1975) and a more recent one in economics (Cunha and Heckman, 2008; Cunha et al., 2010; Attanasio et al., 2020a,c). Latent factor analysis is a model-based approach that facilitates the study of maternal and child developmental trajectories by reducing measurement error and the dimensionality of the outcomes.

We construct the factor scores by assuming a separate measurement system for each domain and then employ Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) to select a concise set of measures. This approach helps us identify key factors that best represent the underlying constructs within each domain, while maintaining simplicity and efficiency in the measurement process. Following Agostinelli and Wiswall (2016), the scaling of each factor is standardized by normalizing the measure with the highest factor loading to one, while maintaining the same measure at all time points. The location is fixed by normalizing the means of the latent factors to zero for the control group at the initial time point (6 months). This approach ensures consistent and comparable scaling across the factors over the different time points in the analysis, allowing us to capture the growth of the latent factors over time.11

To close the model, we connect factor scores over time and capture the dynamic evolution of the child’s latent human capital. We follow Cunha and Heckman (2008); Attanasio et al. (2020a) and specify the production function for child development as:

| (1) |

where and are vectors for child skills in treatment arm —where indicates the control group, indicates the treatment group, and the baseline non-depressed—at time and respectively. stands for parental investment, which occurs between the realizations of and 12. is maternal mental health and functioning at time which we conceptualize as a capital input, contains baseline covariates measured before the treatment assignment, and is the vector of random shocks to child development. We allow the distribution of the latent factors and the parameters of the production function to vary by the child’s age (we estimate one production function at age 12 months and another one at age 36) and by intervention arm .

Allowing the factors and the parameters to vary by intervention arm, this model can be seen as a generalization of a Kitagawa-Oaxaca-Blinder decomposition (Kitagawa, 1955; Oaxaca, 1973; Blinder, 1973). The intervention can act through two main mechanisms: a change in the level of inputs, parental investments and maternal health; and a change in the returns to inputs, i.e. the efficiency with which the inputs translate into child outcomes. This change in efficiency can happen through a combination of changes in TFP, i.e. a different intercept and a shift of the whole production function upwards or downwards, and changes in input-specific-returns, i.e. a different slope of the production function and shift in the derivative between child development and a particular input or .13

We present illustrative examples of the pathways through which the intervention may impact the outcomes. First, it may increase the level of inputs, including maternal mental health and parental investments. For instance, the intervention could alleviate maternal depression by facilitating mothers’ engagement in activities that provide them with a sense of achievement and enjoyment through behavioral activation. Alternatively or in addition, it might encourage mothers to dedicate more quality time to their children and invest in enriching resources like new toys and educational materials, thereby enhancing the home environment (parental investment).14

The intervention may also alter the production function, influencing the way that inputs translate into outputs. For example, the intervention may increase the productivity of each unit of maternal time spent with the child by improving maternal focus and empathy, or by inducing a more age-appropriate use of time and physical resources. Conversely, it could potentially diminish the productivity of maternal mental health if there are decreasing returns. In particular, cases of maternal depression shifting from moderate to mild may exert a weaker influence on child development than cases where the shift is from severe to moderate depression.

The analysis is conducted in two steps: Firstly, we employ maximum likelihood to estimate the factor model and extract the predicted factor scores, as described in detail in Appendix Section D.1. The factor scores are then used to assess the causal impact of the intervention on maternal mental health and child outcomes at each time point. The results of this reduced-form analysis are discussed in Section 4.

In the second step, we estimate the parameters of equation (1), aggregating the reduced-form results of the first step in two systems of equations—one at age 12 and the other at age 36 months. Since we lack instrumental variables that might induce quasi-exogenous variation in the inputs of the production function, this analysis is descriptive. Yet, this synthesis helps us explore the reasons why intervention effects on maternal mental health did not spillover to child development. The results of the production function estimates are presented in section 5.

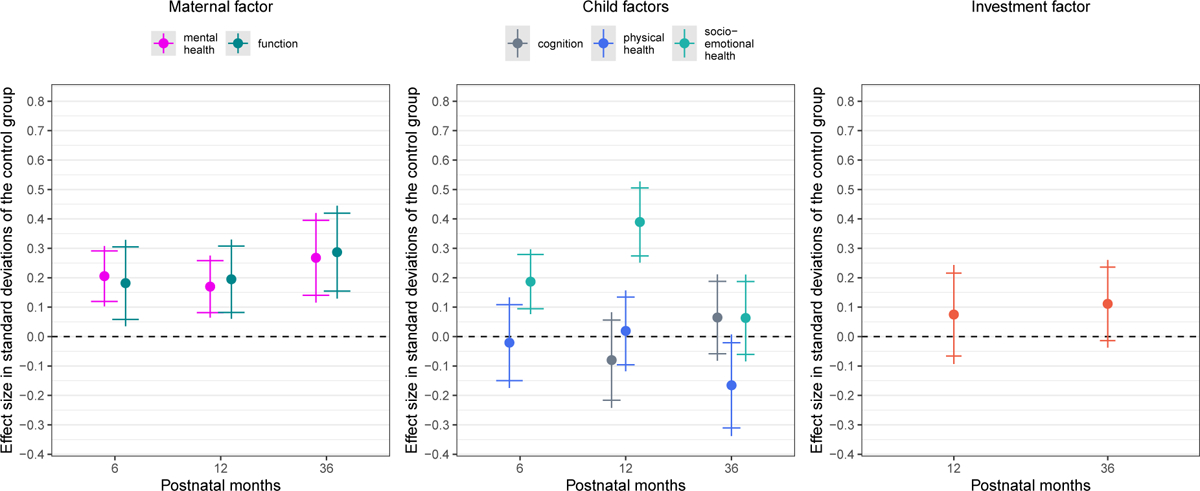

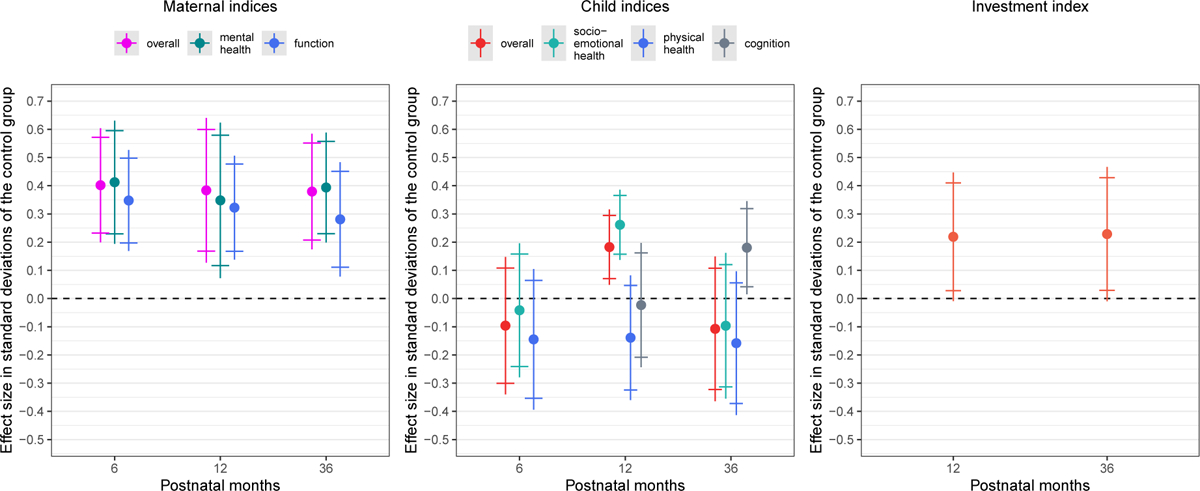

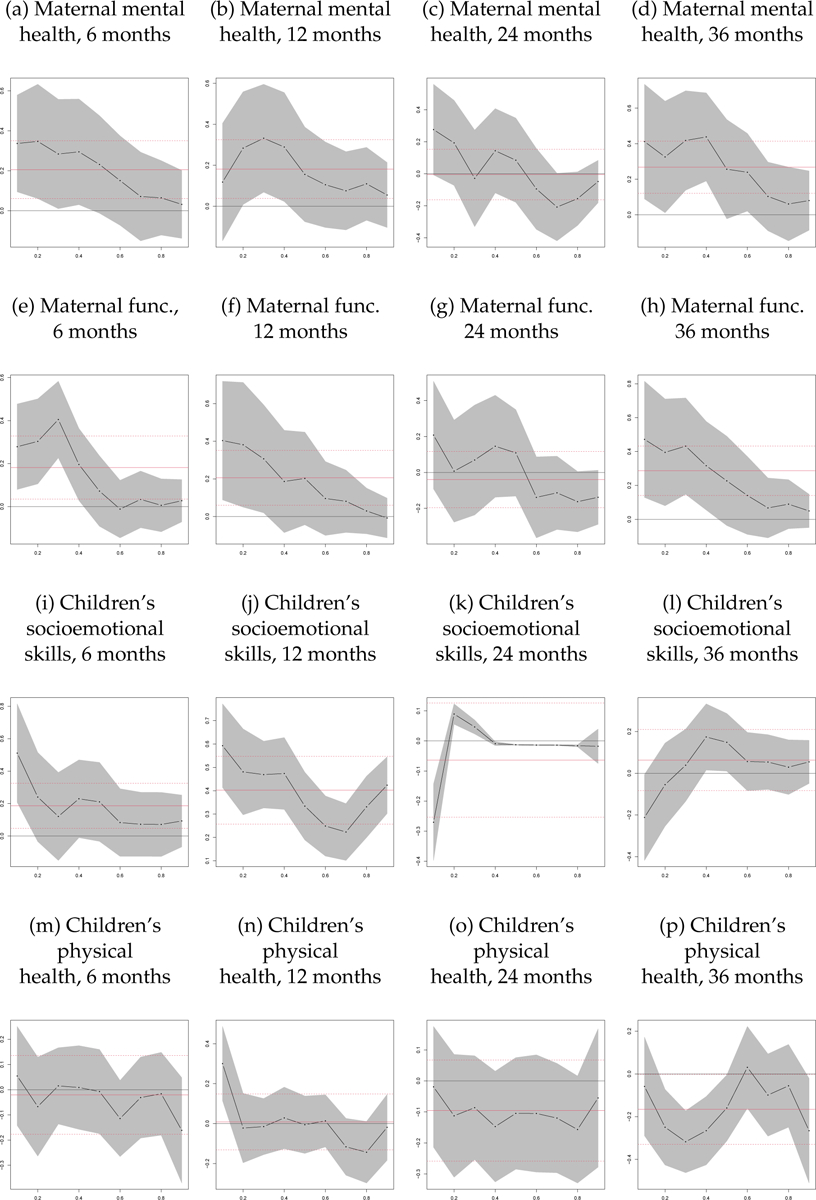

4. Treatment effects

We evaluate the impact of the perinatal psychosocial intervention on maternal mental health, daily functioning, and child skills during the first three years of life leveraging the cluster-randomized nature of the intervention and using ordinary least squares. We estimate intention-to-treat (ITT) effects on the latent factor scores for the domains of maternal mental health, maternal functioning, child cognition, physical, and socioemotional skills, and parental investment (Table 2 and Figure 2). Table 2 reports the estimated ITT on the latent factors normalized to mean zero and standard deviation 1 for the control group at the initial time point (6 months) only, to understand the evolution of the latent factors over time, while Figure 2 and Appendix Table A22 report ITT on latent factors that are normalized to mean 0 and standard deviation 1 at each time point, to allow for comparison of effect sizes in standard deviation units. For completeness, we also report ITT effects on each individual measure in Appendix Tables A18–A21.

Table 2:

Trajectory of Summary Indices

| Measurement | Control | Treatment | Nondep. | Adjusted Beta | s.e. | p-val | N | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | Mean | |||||

| Maternal Factor Scores | ||||||||

| Mental Health (6 months) | 0 | 1 | 0.160 | 0.648 | 0.205 | 0.052 | 0.000 | 929 |

| Mental Health (12 months) | −0.002 | 0.703 | 0.067 | 0.455 | 0.119 | 0.038 | 0.002 | 940 |

| Mental Health (36 months) | −0.023 | 0.760 | 0.078 | 0.399 | 0.204 | 0.059 | 0.001 | 889 |

| Functioning (6 months) | 0 | 1 | 0.108 | 0.547 | 0.182 | 0.075 | 0.015 | 929 |

| Functioning (12 months) | 0.013 | 0.781 | 0.138 | 0.382 | 0.152 | 0.054 | 0.005 | 940 |

| Functioning (36 months) | 0.043 | 0.856 | 0.139 | 0.365 | 0.246 | 0.069 | 0.000 | 889 |

| Child Factor Scores | ||||||||

| Physical Health (6 months) | 0 | 1 | −0.016 | −0.034 | −0.021 | 0.079 | 0.792 | 929 |

| Physical Health (12 months) | −0.039 | 0.799 | −0.003 | −0.011 | 0.015 | 0.056 | 0.784 | 940 |

| Physical Health (36 months) | −0.026 | 0.806 | −0.136 | 0.007 | −0.134 | 0.071 | 0.060 | 889 |

| SE Skills (6 months) | 0 | 1 | 0.167 | 0.100 | 0.187 | 0.056 | 0.001 | 940 |

| SE Skills (12 months) | −0.183 | 0.842 | 0.168 | 0.082 | 0.328 | 0.059 | 0.000 | 940 |

| SE Skills (36 months) | 0.864 | 0.907 | 0.917 | 0.966 | 0.057 | 0.068 | 0.400 | 889 |

| Cognition (12 months) | 0 | 1 | −0.059 | 0.069 | −0.080 | 0.083 | 0.334 | 940 |

| Cognition (36 months) | 0.041 | 0.426 | 0.061 | 0.033 | 0.028 | 0.031 | 0.386 | 889 |

| Investment Factor Scores | ||||||||

| Investment (12 months) | 0 | 1 | 0.062 | 0.448 | 0.075 | 0.086 | 0.382 | 940 |

| Investment (36 months) | −0.002 | 0.643 | 0.041 | 0.230 | 0.072 | 0.049 | 0.143 | 889 |

SE skills = socioemotional skills. The first two columns report the mean and standard deviation of the outcome variables in the control group. The following columns report the means for the treatment group and the group of mothers who were non-depressed at baseline (Nondep.). Adjusted Beta coefficients are obtained from the regressions of items on the treatment indicator and its interactions with the (demeaned) baseline covariates including baseline PHQ Total, baseline WHODAS Total, baseline PSS Total, mother’s baseline age, weight, height, waist circumference and blood pressure, family structure, grandmother being resident, total adults in the household, people per room, number of living children (split by gender), whether the index child is the first child, parental education levels, asset-based SES index, life events checklist score, interviewer fixed effect, union council fixed effect and days from baseline. All estimations control for child gender and age (in days). Standard errors clustered at the village-cluster level are reported in the s.e. column. Reported p-values and standard errors refer to the adjusted beta coefficient. N reports the number of observations of each analysis. Factor scores are coded so that a higher score always indicates a better outcome.

Figure 2:

Coefficient Plots of Factors

Notes: Plot of the adjusted beta coefficients reported in Table A22 and their 90% and 95% confidence intervals. Latent factors are normalized to mean 0 and standard deviation 1 in the control group at each time point, to allow comparability of effect sizes in standard deviations. Coefficients are obtained from the regressions of items on the treatment indicator and its interactions with the (demeaned) baseline covariates including baseline PHQ Total, baseline WHODAS Total, baseline PSS Total, mother’s baseline age, weight, height, waist circumference and blood pressure, family structure, grandmother being resident, total adults in the household, people per room, number of living children (split by gender), whether the index child is the first child, parental education levels, asset-based SES index, life events checklist score, interviewer fixed effect, union council fixed effect and days from baseline. All estimations control for child gender and age (in days). Standard errors clustered at the village-cluster level. Factor scores are coded so that a higher score always indicates a better outcome and standardized to have mean 0 and SD 1 in the control group at each time point.

As our baseline and follow-up samples were not completely balanced along baseline characteristics, the regressions control not only for child age in days, interviewer fixed effects, and union council fixed effects (stratification unit), but also for the full set of baseline characteristics (demeaned) and their interactions with the treatment indicator (adjusted ).15 Note that we can only identify the overall causal effect of the THPP+ intervention and not the causal effect of recovering from depression or of any individual component of the intervention, such as behavioral activation or group-based aspects of the treatment. Including interactions with treatment allows us to control for possible heterogeneity in the impacts of baseline characteristics on outcomes. Reported standard errors are clustered at the village cluster level (i.e., the randomization unit). We also compute p-values using randomization inference based on Young (2019) with the randomization permuted at the cluster level. We observe minimal changes in the p-values due to the randomization inference, as shown in Appendix Tables A27–A28.

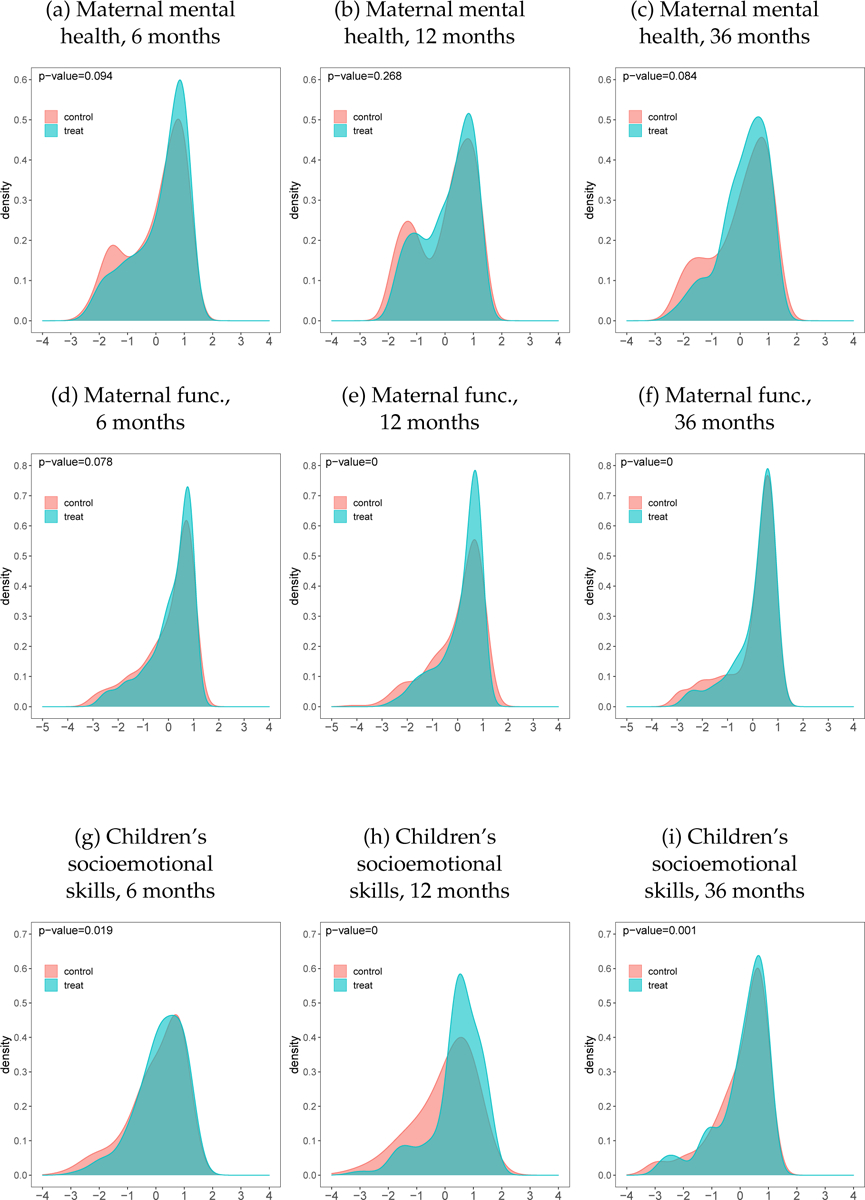

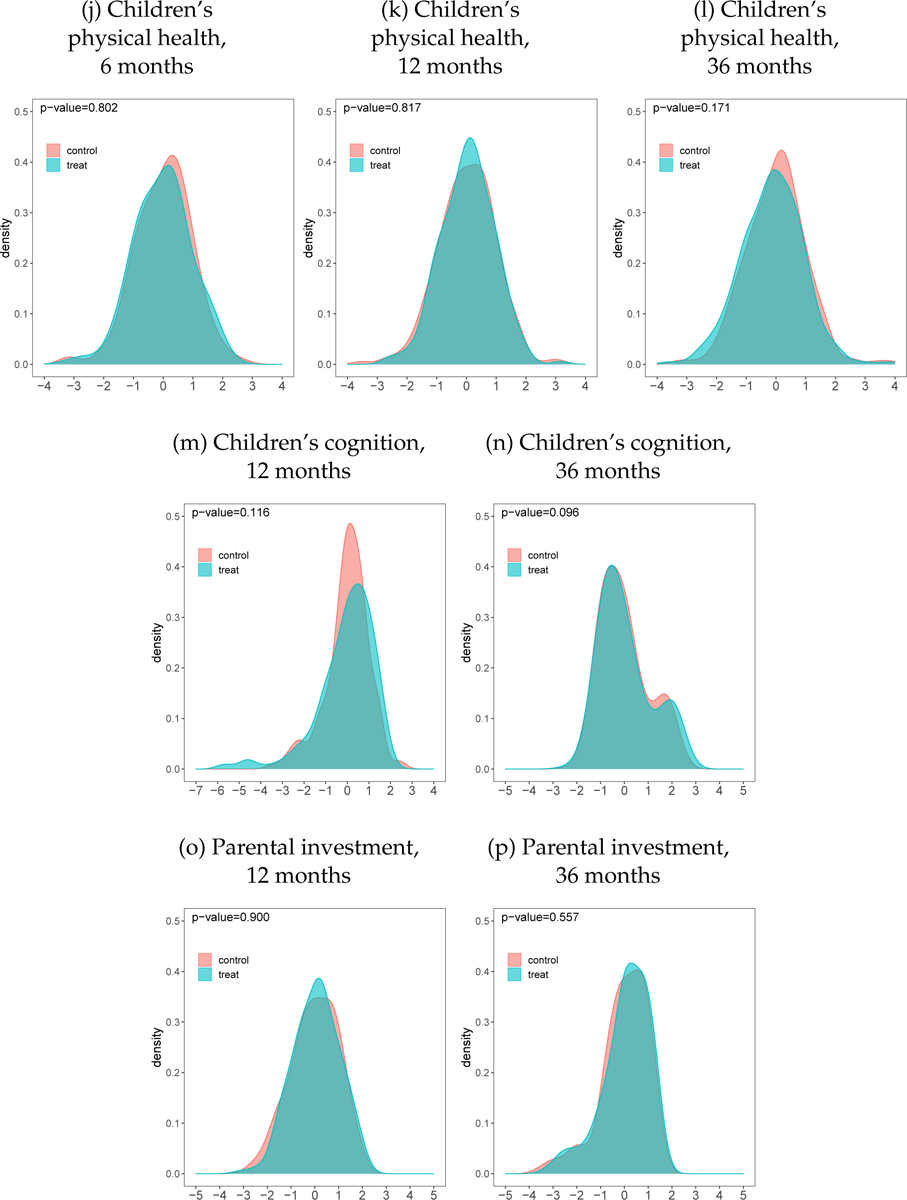

We additionally present results of the intervention on the distribution of outcomes. Figure A6 presents the estimated densities of the latent factors for the control and treatment clusters. To compare the CDFs of the two groups, we perform a Kolmogorov-Smirnov test with bootstrap.16 Quantile treatment effects are reported in Appendix Figure A7.

4.1. Maternal mental health and functioning

The intervention is effective in improving the mother’s condition at 6, 12, and 36 months post-partum. The upper panel of Table 2 and the first panel of Figure 2 present the adjusted beta coefficient plots of latent factor scores. Improvements range between 0.17 and 0.27 standard deviations in maternal mental health, and between 0.18 and 0.29 SD in maternal functioning, with the largest effect sizes observed at 36 months.

Plots of the outcome distributions show a rightward shift in the latent factor score for maternal mental health throughout the trial period. These effects are bigger in the lower half of the distribution, although this difference in quantile treatment effects is not always statistically significant.

Treatment effects on individual maternal outcomes are reported in Appendix Table A18. Treated women experienced a significant reduction in depression scores (PHQ-9) at 6 and 36 months postpartum relative to women in the control clusters (p-values 0.014 and 0.001, respectively). Splitting the PHQ score into different categories, the greatest reduction is concentrated in the moderate-severity category (15 ≤ PHQ-score ≤ 19), with an increase in the women in the minimal category (PHQ-score ≤ 4). Treated women were less likely to have a major depression episode at 6, 12, and 36 months, with a reduction of likelihood ranging between 7 and 12 percentage points (p-values 0.011, 0.011, and 0.001, respectively). Their stress score is significantly lower, and their daily functioning significantly better than in the control group. Overall, we observe positive and significant treatment effects across multiple indicators of maternal depression, stress, and functioning in the three waves analyzed.

4.2. Parental investment and behaviour

The adjusted beta coefficients related to the parental investment factor score are all positive (0.08–0.11 SD), but not statistically different from zero. These treatment effects, even if they were to be more precisely estimated, would suggest only modest improvements when compared to other global studies focusing on at-risk parents (Rayce et al., 2017; Jeong et al., 2021).

Analyzing the different measures of parental investment in Appendix Table A21, we find the intervention improved most subscales of the HOME inventory indicating maternal responsivity, avoidance of restrictions and punishment, organization of the child’s environment, and provision of appropriate learning materials at 12 months postpartum. At 36 months, the intervention had positive effects on the total HOME score, acceptance, and learning materials, albeit imprecisely estimated, but only small positive and sometimes negative effects on other subscales.

4.3. Child outcomes

The estimated treatment effects on child outcomes are generally noisier than on mothers. The intervention seems to have no clear effect on cognition—with estimated ITT coefficients smaller than 10% of a standard deviation and hovering around zero, or on physical health, which displays both slightly positive and mildly negative adjusted beta coefficients. Notably, the intervention has a sizeable, albeit transitory effect on socioemotional skills: the estimated ITT at 6 and 12 months are 0.19 and 0.39 SD respectively, indicating considerable improvements. However, these treatment-control differences fade out by the 36-month mark, when the estimated ITT effect is only 0.06 and it is neither economically meaningful nor statistically different from zero.

The transitory effect might have persistent consequences, even if it does not itself persist. For instance, socio-emotional skills in infancy might fuel self-regulation, interaction, and curiosity (and possibly other domains that are hard to measure, especially at an early age) which in turn might improve school achievement and later life outcomes. In line with this, in the next section, we report small but positive estimates of cross-skill productivity between socioemotional ability and cognition up until age 3.

Looking at the individual indices in Appendix Tables A19–A20, we observe significant improvements only in certain socioemotional and cognitive domains. The total ASQ-SE score is generally lower (indicating better socioemotional skills) in the treatment group. Looking at the sub-components of ASQ-SE shows that, at 12 months, the improved ASQ-SE in the treatment group is driven by significant improvements in self-regulation (measuring the child’s ability to regulate her emotions and adjust to new environments). These effects are mainly driven by male children. At 36 months, the intervention impacts are once again on self-regulation and now, also, on autonomy.

In terms of cognitive outcomes, the estimated treatment effect on the Bayley receptive domain score (one of the two components of Bayley-III) is significantly positive at 36 months, with a score increase of 0.39 (p-value 0.06) in the treatment group, which brings the mean scores of the treatment group close to the scores of the non-depressed group. However, treatment effects on the aggregate cognition index and factor score are small (0.09 and 0.07 SD, respectively) and imprecisely estimated.

Looking at the distribution of outcomes, there is a shift to the right in the distribution of children’s socioemotional skills in the treatment group in the first 12 months of the trial. However, at 36 months, the two densities overlap again suggesting a short-term effect. Quantile treatment effect analysis yields larger effects in the lower half of the distribution in the first two years, which become insignificant at 36 months postpartum (Appendix Figure A7).

The distribution of the child cognition factor shows a scale shift at 12 months and a small location shift at 36 months postpartum. For children’s physical health, the densities for the control and treatment groups overlap and the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test cannot reject that they are equal. Quantile treatment effects are also not generally different from zero in any part of these distributions.

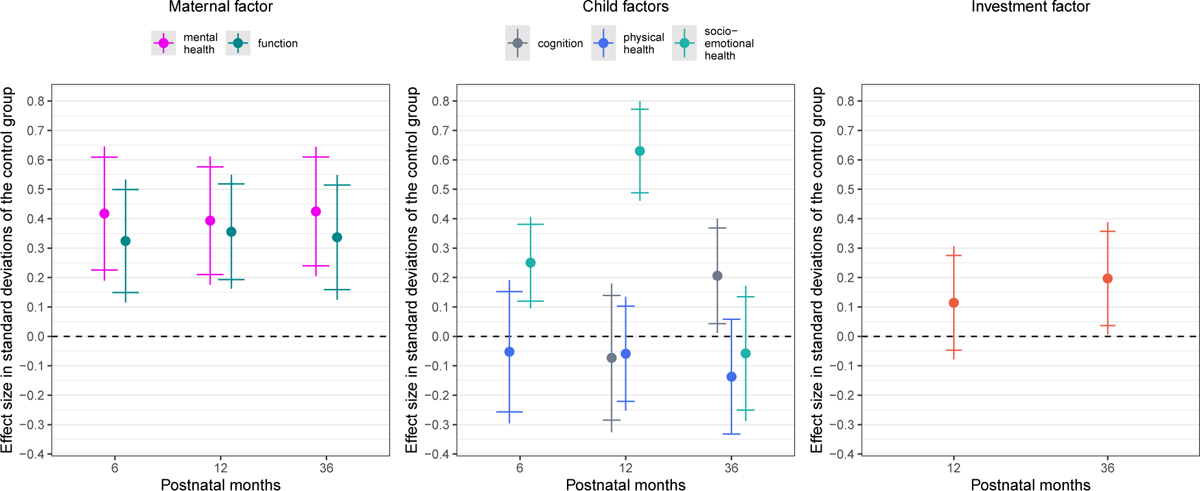

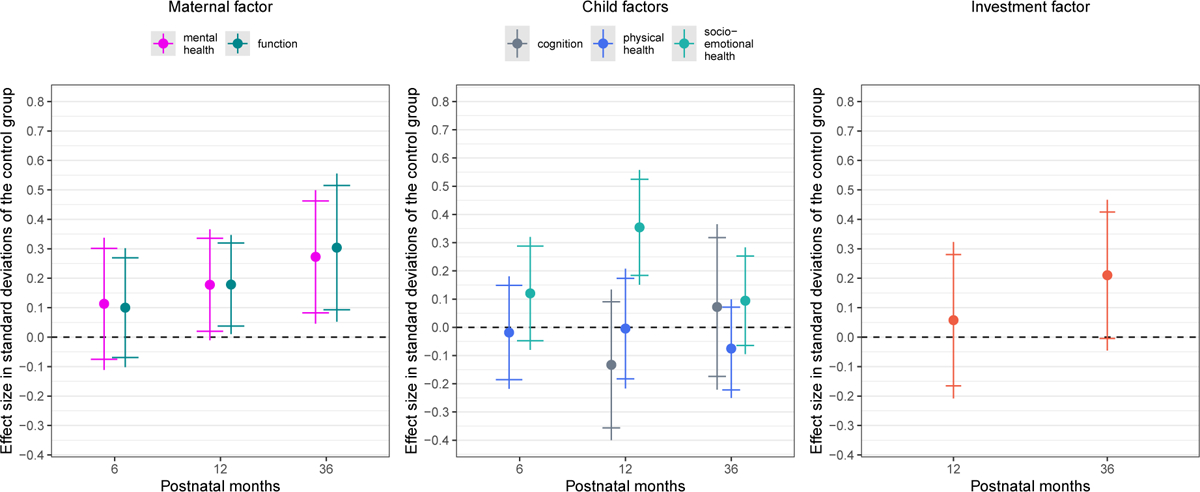

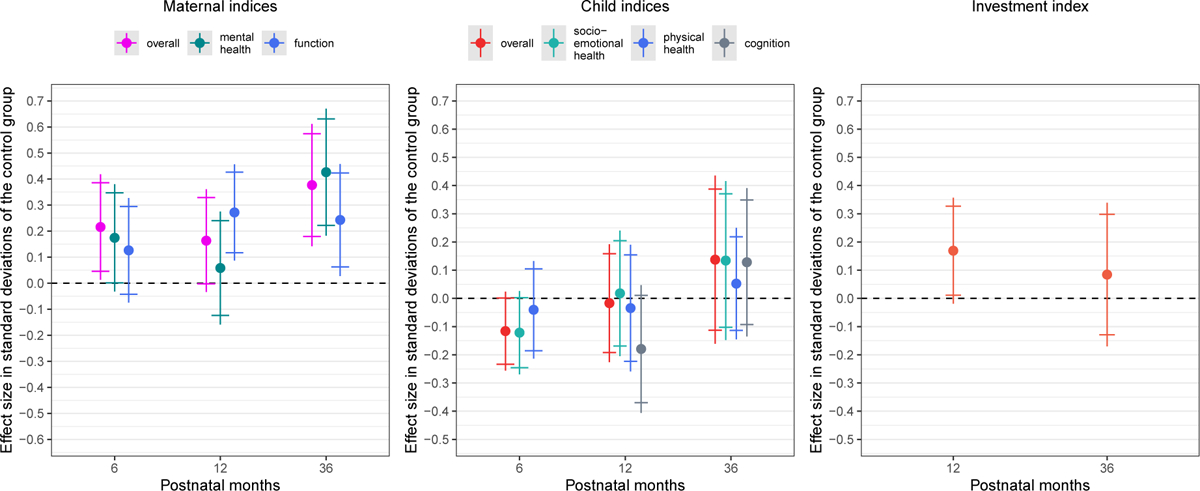

4.4. Heterogeneity

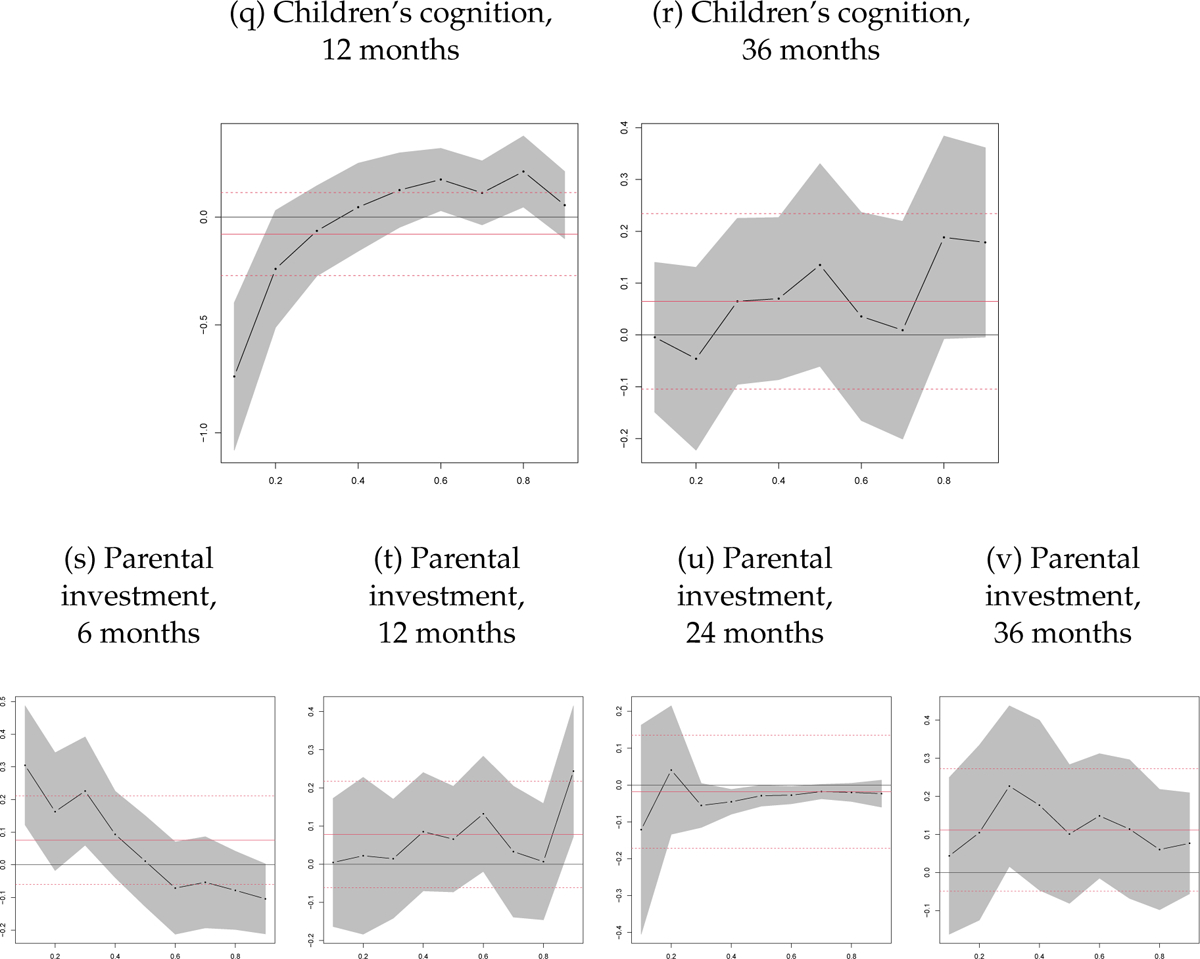

Exploring treatment effect heterogeneity on maternal outcomes by gender of the index child reveals that the estimated benefits are larger for the mothers of boys (Figures 3–4 and appendix tables A29–A31). As discussed earlier, intervention effects on investment and child skills also show a tendency to be stronger for boys. There is well-documented son preference in South Asia, and some evidence that women who have sons are treated better by the family than women who have daughters (Sathar et al., 2015; Milazzo, 2018; Bhalotra et al., 2020). It seems plausible that women who are in a generally more supportive environment are more responsive to treatment, and this would explain our finding. However, we can imagine the reverse, i.e., that treatment effects are larger where the environment is harsher. Indeed, in Baranov et al. (2020) we found that a similar intervention (THP) run on a different sample of new mothers in rural Pakistan was more effective for mothers of girls in a 7-year follow-up. The length of the follow-up aside, the intervention analyzed in this study (THPP+) differs in duration and in intervention modality (see Section 1 for details), making it hard to compare the findings. THPP+ was peer-delivered, while THP was delivered by trained community health workers. One possible explanation is that peers (other mothers in the community) might implicitly reinforce gender norms, whereas community health workers might act to empower mothers of girls. We have no hard evidence of this potential channel, but it is a relevant consideration to highlight when considering task-shifting to peers in an attempt to scale up interventions.

Figure 3:

Coefficient Plots of Factors (Boys)

Notes: Plot of the 90% and 95% confidence intervals and the adjusted beta coefficients obtained from the regressions, using only the sample of families where the index child is a boy, of items on the treatment indicator and its interactions with the (demeaned) baseline covariates including baseline PHQ Total, baseline WHODAS Total, baseline PSS Total, mother’s baseline age, weight, height, waist circumference and blood pressure, family structure, grandmother being resident, total adults in the household, people per room, number of living children (split by gender), whether the index child is the first child, parental education levels, asset-based SES index, life events checklist score, interviewer fixed effect, union council fixed effect and days from baseline. All estimations control for age (in days). Standard errors clustered at the village-cluster level. Factor scores are coded so that a higher score always indicates a better outcome and standardized to have mean 0 and SD 1 in the control group at each time point.

Figure 4:

Coefficient Plots of Factors (Girls)

Notes: Plot of the 90% and 95% confidence intervals and the adjusted beta coefficients obtained from the regressions, using only the sample of families where the index child is a girl, of items on the treatment indicator and its interactions with the (demeaned) baseline covariates including baseline PHQ Total, baseline WHODAS Total, baseline PSS Total, mother’s baseline age, weight, height, waist circumference and blood pressure, family structure, grandmother being resident, total adults in the household, people per room, number of living children (split by gender), whether the index child is the first child, parental education levels, asset-based SES index, life events checklist score, interviewer fixed effect, union council fixed effect and days from baseline. All estimations control for age (in days). Standard errors clustered at the village-cluster level. Factor scores are coded so that a higher score always indicates a better outcome and standardized to have mean 0 and SD 1 in the control group at each time point.

We investigated heterogeneity by birth-order of the index child, an asset-based index of socioeconomic status of the family, education of the mother, and baseline depression severity (PHQ-9 total score). We find no systematic patterns here.

4.5. Discussion

The group-based, peer-delivered psychosocial intervention was effective at achieving one of its targets, which was improving maternal mental health and daily functioning. These improvements in well-being are complemented by smaller and imprecisely estimated increases in parenting behavior of 8 to 11% of a standard deviation, and by a sizeable but transitory change in children’s socioemotional development. This improvement in child skills at 12 months appears to be a direct effect of the intervention, which included training and support for child development.

Our results do not appear to be driven by attrition. Attrition-adjusted estimates using inverse probability weighting (IPW) and Lee Bounds (Lee, 2009) are shown in Appendix Table A6, with gender-specific results in Appendix Table A7. Our results are robust to the IPW correction, which only marginally changes the estimated coefficients and their precision. The attrition-corrected Lee bounds are wide, but in the sample of mothers of boys (in which baseline characteristics are more balanced) show positive and significant effects on maternal mental health and on child socioemotional skills both at 6 and 12 months.

To provide a benchmark for the effectiveness of the intervention and to put the magnitude of the treatment effects in perspective, we compare the adjusted beta coefficients with the mean level of the summary indices for the mothers who were not depressed at baseline. Since the mean summary index for the control group is standardized to be zero, the average outcome for the nondepressed mothers represents the association between prenatal depression and outcomes. We call this descriptive statistic the “depression gap” and display this in Appendix Table A33, Columns 5–7.

The intervention acted to narrow depression gaps, tending to bring the medium-term outcomes of perinatally depressed women closer to the outcomes of women who were in the same pregnancy cohort but not depressed at baseline. This is the case for child socioemotional skills and parental investment.17 The depression gap in child health and cognitive skills is often small and imprecisely estimated. As such, there was limited leeway for the intervention to improve these domains.

The results in this paper build upon our findings in Maselko et al. (2020). We extend that analysis in the following ways. We investigate dynamics, exploring multiple indicators and their evolution throughout the study period. As child development is not a linear process, a more granular approach is of substantive importance. At each age, we estimate treatment effects by gender of the child and on the distribution of outcomes rather than only at the mean. We provide treatment effects on a broader set of outcomes (including, for instance, the ASQ-SE for socioemotional development). We use aggregate summary indices and factor scores to provide summary measures of maternal well-being and child development and to improve statistical power. We also adopt a less restrictive statistical specification.18 A final and key differentiation is that we now impose some structure on the dynamic evolution of children’s skills, accounting for the trajectory of maternal mental health, functioning, and parenting, and estimate the production function for skills at age 12 and 36 months. We discuss this next.

5. The Technology of Skill Formation

The results above indicate that the intervention improved maternal mental health, but these enhancements did not consistently transfer into lasting improvements in child skills. This discrepancy is at odds with some of the descriptive literature comparing the socioemotional outcomes of children of depressed and non-depressed mothers (Herba et al., 2016; Leung and Kaplan, 2009; Gaynes et al., 2005), but consistent with other literature that finds that moderate levels of maternal depression are not systematically associated with impaired child development (Laplante et al., 2008; DiPietro et al., 2006). To reconcile the suite of reduced form findings and understand the mechanisms by which the intervention might have influenced the outcomes, we impose the simplifying structure discussed in Section 3 on the dynamic evolution of the child’s latent human capital.

We contribute to the literature on mental health and child development in two related ways. First, we include in the model two dynamic latent factors measuring maternal mental health and functioning . Their measurement is consistent over time and uses state-of-the-art measurements for the screening and assessment of three relevant dimensions of maternal mental health—depression, stress, and daily functioning. We estimate their contribution to the production function of the child’s cognitive, socioemotional, and physical health. Earlier related studies at best include a time-invariant measure of maternal characteristics such as cognitive skills, physical health, or noncognitive skills (Cunha and Heckman, 2008; Cunha et al., 2010; Attanasio et al., 2022b). To distinguish maternal mental health from parental investments, we conceptualize it as capital in the production function, similar in principle to the conceptualization of physical health as capital (Grossman, 1972).

Second, this study is the first to estimate how a psychosocial intervention targeting the mother might influence the production function of children’s skills, allowing some parameters of the production function to vary with the intervention. Similar to a Kitagawa-Oaxaca-Blinder decomposition (Kitagawa, 1955; Oaxaca, 1973; Blinder, 1973), we allow the intervention to act through two potential mechanisms: a change in the level of parental inputs; and a change in the productivity of these inputs, i.e. the slope of the production function.

These two channels are embedded into our specification of the dynamic model of skill formation. For ease of interpretation and estimation, we assume that the production functions for child socioemotional skills, physical health, cognition, parental investment, and maternal mental health described in equation (1) are log-linear (Cobb Douglas).19

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

where , and stand for physical health, socioemotional skills, and cognition of the child, respectively. Eq. (2) reflects that children’s health and cognition in period are functions of the previous period stock of skills and health , investments made by parents up to that point , parental education, as well as maternal mental health and functioning denotes the same baseline covariates used in the treatment effect estimation in Section 4, notably the mother’s baseline age, weight, height, waist circumference and blood pressure, family structure, grandmother being resident, total adults in the household, people per room, number of children (split by gender), whether the index child is the first child, asset-based SES index and child gender.20 stands for total factor productivity (TFP) and represents unobserved shocks to child development. Eq.(3) and (4) model the evolution of the main inputs: the stock of maternal mental health and the flow of parental investment. The same control variables are included as in Eq.(2).

We estimate the production and investment functions in equations (2)–(4) in two stages: at 12 months and at 36 months. To do so, we use the factor scores resulting from the measurement system discussed above and in Appendix Section D.1. We exclude lagged cognition in the estimations for 12 months, as we did not measure cognition at 6 months.

While all of the distributions of latent factors are allowed to be different across treatment, control, and baseline non-depressed mothers—capturing potential changes in the level of inputs—we only allow the coefficients of and to vary with treatment status —capturing potential changes in slope and therefore productivity. We do this by including an indicator for the treatment group (treat) and an indicator for the group of mothers who were non-depressed at baseline (nondep) and interacting them with parental investment and maternal mental health (the two main inputs of interest). This simplifying assumption focuses the estimation on the two main channels that were targeted by the intervention: maternal mental health and investments. It allows us to study how the productivity of maternal mental health and investments changes as a function of the intervention.

Theoretically, we may observe the productivity of mental health increase or decrease as a result of the intervention. On the one hand, if the true relationship between the input (lagged maternal mental health) and the output (child skill development) is subject to diminishing returns, then an improvement in maternal mental health due to the intervention could move the treatment group further up and to the right along the curve, where the slope is flatter (see this notional curve in Figure 5a). The estimated relationship between the input and output in the control group would then exhibit a lower constant and a steeper slope than the treatment group. This would manifest as a positive parameter on the interaction between TFP and treatment (TFP × treat) and a negative interaction between maternal mental health and treatment (motherMH × treat). Plotting the observed non-parametric relationship between maternal mental health at 6 months, , and child skills at 12 months, , using the control group data does in fact indicate a nonlinear, concave relationship (Figure 5b), similar to Figure 5a and in line with the descriptive findings of Laplante et al. (2008); DiPietro et al. (2006).21

Figure 5:

Relationship between maternal mental health (6m) and child skills (12m)

Notes: (a) Theoretical representation of a concave relationship between maternal mental health (input) and children skills (output), and the consequence of log-linearization at different average levels of the input. (b) Kernel-weighted local polynomial smoothing of the relationship in the control group between maternal mental health at 6 months and: child socioemotional skill factor (solid dark line), child cognition factor (dashed grey line), and child physical health factor (dotted blue line) at 12 months. (c) Left-y-axis: Kernel-weighted local polynomial smoothing and 95% confidence interval of the relationship between maternal mental health at 6 months and child socioemotional skill factor at 12 months in the control group (solid dark line) and the treatment group (dotted blue line). Right-y-axis: kernel density estimation of the distribution of maternal mental health at 6 months in the control group (dash-dotted dark line) and the treatment group (dotted gray line).

Alternatively, the intervention could change the shape and the location of the production function: for example, intervention components not specifically targeting maternal mental health (e.g. improving mother-child bonding, seeking social support) may change the relative productivity of mental health, parental investments, or both. These non-mental health components of the intervention might reinforce and complement the intervention-lead effects on maternal mental health, for example allowing mothers who have recovered from depression to engage in more fruitful parental interaction with the children. This would lead to a positive coefficient on the interaction between maternal mental health and treatment (motherMH × treat). But the non-mental health component of the intervention could also act as a substitute, shielding children from maternal depression and improving particularly the outcomes of children whose mothers did not recover from depression even after therapy. This would lead to a negative coefficient for motherMH × treat. Plotting the observed non-parametric relationship between maternal mental health at 6 months, , and child socioemotional skills at 12 months, separately for treated and control group indicates a potential substitution effect, with greater intervention effects for children whose mothers did not recover from depression (Figure 5c).

We now turn to the discussion of the empirical estimates of equations 2–4. It is important to remember that we have one instrument (the intervention) and multiple endogenous inputs, for which it is difficult to find a plausible source of exogenous variation. The results of this analysis should therefore be considered as descriptive, similar to the existing literature estimating child skill production functions (see, for instance, the summary of the literature in Table 1 of Attanasio et al., 2022b).

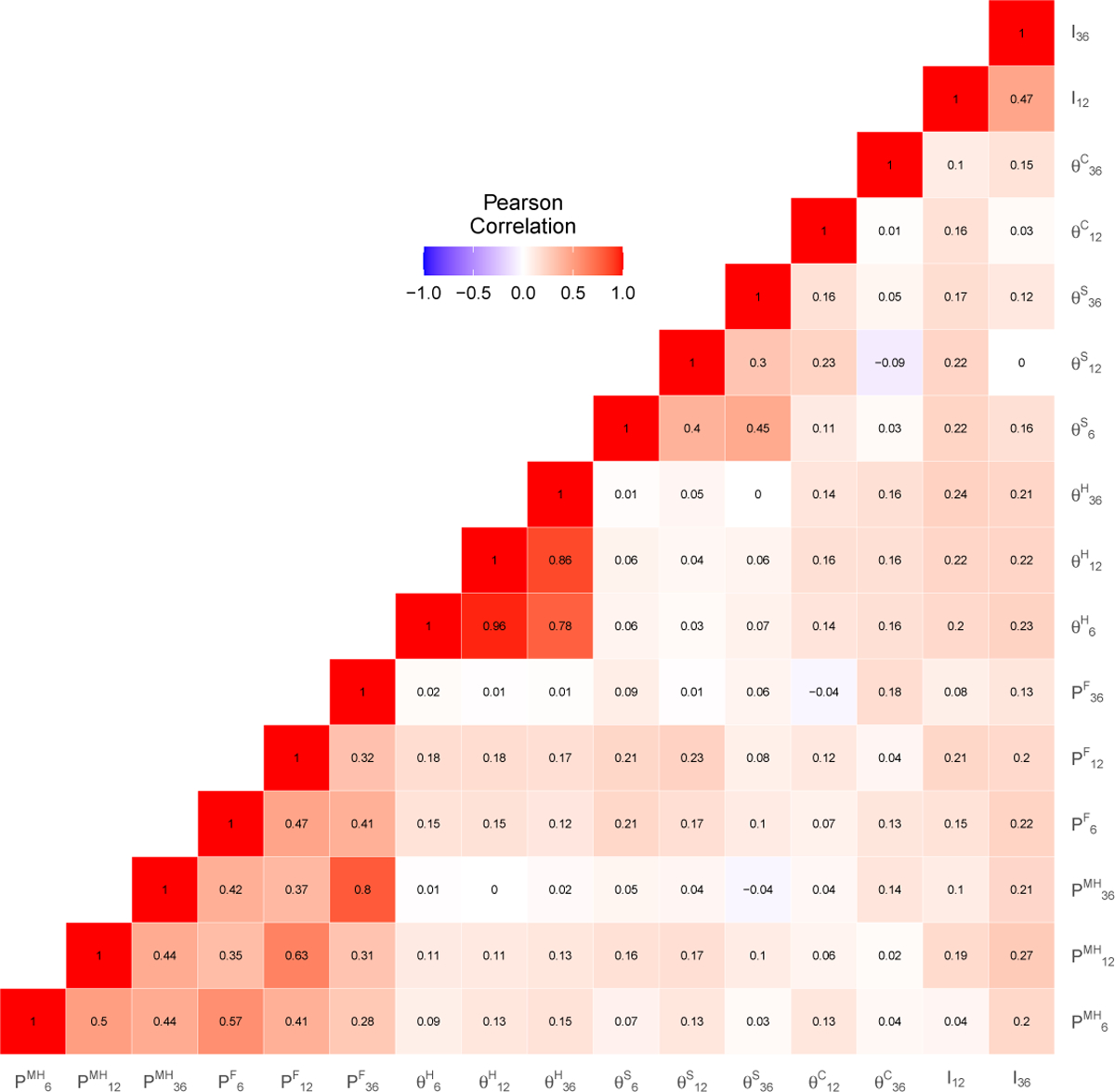

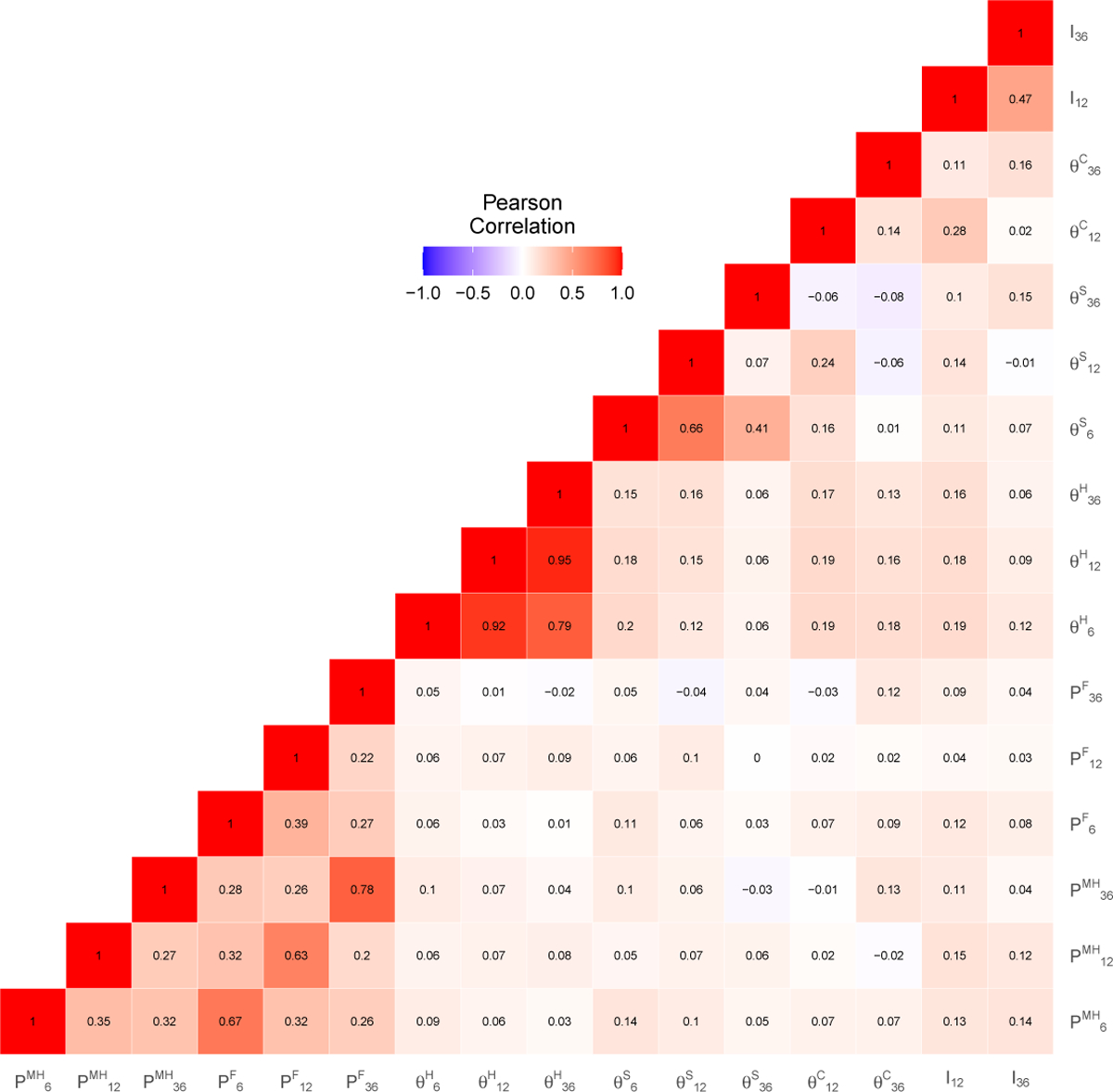

5.1. Estimates of the Technology

Tables 3–4 report estimates for the outcomes at 12 months and 36 months respectively. The estimates reveal that children’s skills and maternal mental health are persistent over time, indicating ‘self-productivity’ in skills. Socioemotional skills, physical health, and maternal mental health exhibit persistence through from 6 to 36 months, while cognitive skills are only clearly persistent from 6 to 12 months. For cognitive and socioemotional skills, self-productivity is larger earlier in childhood. Consistent with estimates of skill formation in other settings (Attanasio et al., 2022b; Bufferd et al., 2012), skills are less predictive across domains—the ‘cross-productivity’ of skills is at least a degree of magnitude smaller than self-productivity, often non-statistically different from zero, except for the predictive power of physical health on cognitive skill development at both 12 and 36 months. Evidence on self- and cross-productivity of skills across domains at very early ages, 0–3, is relatively scarce, therefore providing an important contribution to the literature.

Table 3:

Estimates of the Production Function and Input Equations I

| Socioemotional skills (12m) (1) |

Physical health (12m) (2) |

Cognition (12m) (3) |

Parental investment (12m) (4) |

Maternal mental health (12m) (5) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SE skills (6m) | 0.450*** (0.042) |

0.004 (0.014) |

0.065* (0.035) |

0.034 (0.024) |

0.031 (0.024) |

| physical health (6m) | 0.070 (0.044) |

0.928*** (0.014) |

0.109*** (0.042) |

0.077*** (0.024) |

0.006 (0.022) |

| mother mental health (6m) | 0.117* (0.062) |

0.083*** (0.029) |

0.131* (0.076) |

−0.104 (0.069) |

0.384*** (0.067) |

| mother functioning (6m) | −0.033 (0.053) |

−0.044** (0.020) |

−0.025 (0.045) |

0.081** (0.040) |

0.093** (0.042) |

| investment (12m) | 0.086 (0.082) |

0.030 (0.022) |

−0.016 (0.060) |

0.162** (0.053) |

|

| Interactions | |||||

| mother MH (6m) × treat | −0.199*** (0.076) |

−0.061 (0.038) |

−0.199** (0.096) |

0.101 (0.085) |

−0.022 (0.073) |

| mother MH (6m) × nondep. | −0.052 (0.094) |

−0.133*** (0.034) |

−0.066 (0.094) |

0.106 (0.080) |

−0.155* (0.084) |

| investment (12m) × treat | −0.022 (0.108) |

−0.030 (0.035) |

0.346*** (0.090) |

−0.007 (0.067) |

|

| investment (12m) × nondep. | −0.033 (0.082) |

−0.026 (0.030) |

0.206*** (0.073) |

−0.072 (0.063) |

|

| Total factor productivity (TFP) | |||||

| TFP | −0.567 (0.887) |

−0.465 (0.346) |

4.208*** (0.919) |

0.101 (0.799) |

−0.453 (0.664) |

| TFP × treat | 0.257*** (0.061) |

0.033* (0.020) |

−0.023 (0.058) |

0.065 (0.060) |

0.043 (0.049) |

| TFP × nondep. | 0.243** (0.100) |

0.118*** (0.038) |

−0.069 (0.089) |

0.022 (0.094) |

−0.001 (0.084) |

| Baseline controls | |||||

| SES assets | −0.016 (0.020) |

0.004 (0.007) |

0.009 (0.024) |

0.087*** (0.016) |

−0.019 (0.015) |

| mother’s education (years) | −0.003 (0.006) |

0.005 (0.003) |

−0.004 (0.007) |

0.019*** (0.004) |

0.011** (0.005) |

| husband’s education (years) | 0.001 (0.007) |

−0.006** (0.003) |

−0.002 (0.006) |

0.016** (0.007) |

0.001 (0.006) |

| Observations | 932 | 932 | 927 | 932 | 932 |

| R2 | 0.430 | 0.881 | 0.258 | 0.384 | 0.429 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.387 | 0.873 | 0.202 | 0.340 | 0.387 |

SE= socioemotional skills, MH=mental health. Dependent variables are child outcomes and parental investment and maternal mental health factors at 12 months postpartum. Independent variables include an indicator of treatment status (control, treatment, nondepressed), child and maternal factors at 6 months (except for cognition as we did not measure cognition at 6 months), parental investment factor at 12 months. Maternal mental health and parental investment are interacted with the treatment status. All estimations control for baseline characteristics including, mother’s baseline age, weight, height, waist circumference and blood pressure, family structure, grandmother being resident, total adults in the household, people per room, number of living children (split by gender), whether the index child is the first child, parental education levels, asset based SES index, life events checklist score, interviewer fixed effect, union council fixed effect, days from baseline and child age in days. Robust and clustered standard errors at the cluster level are reported in paranthesis.

Note:

p<0.1;

p<0.05;

p<0.01

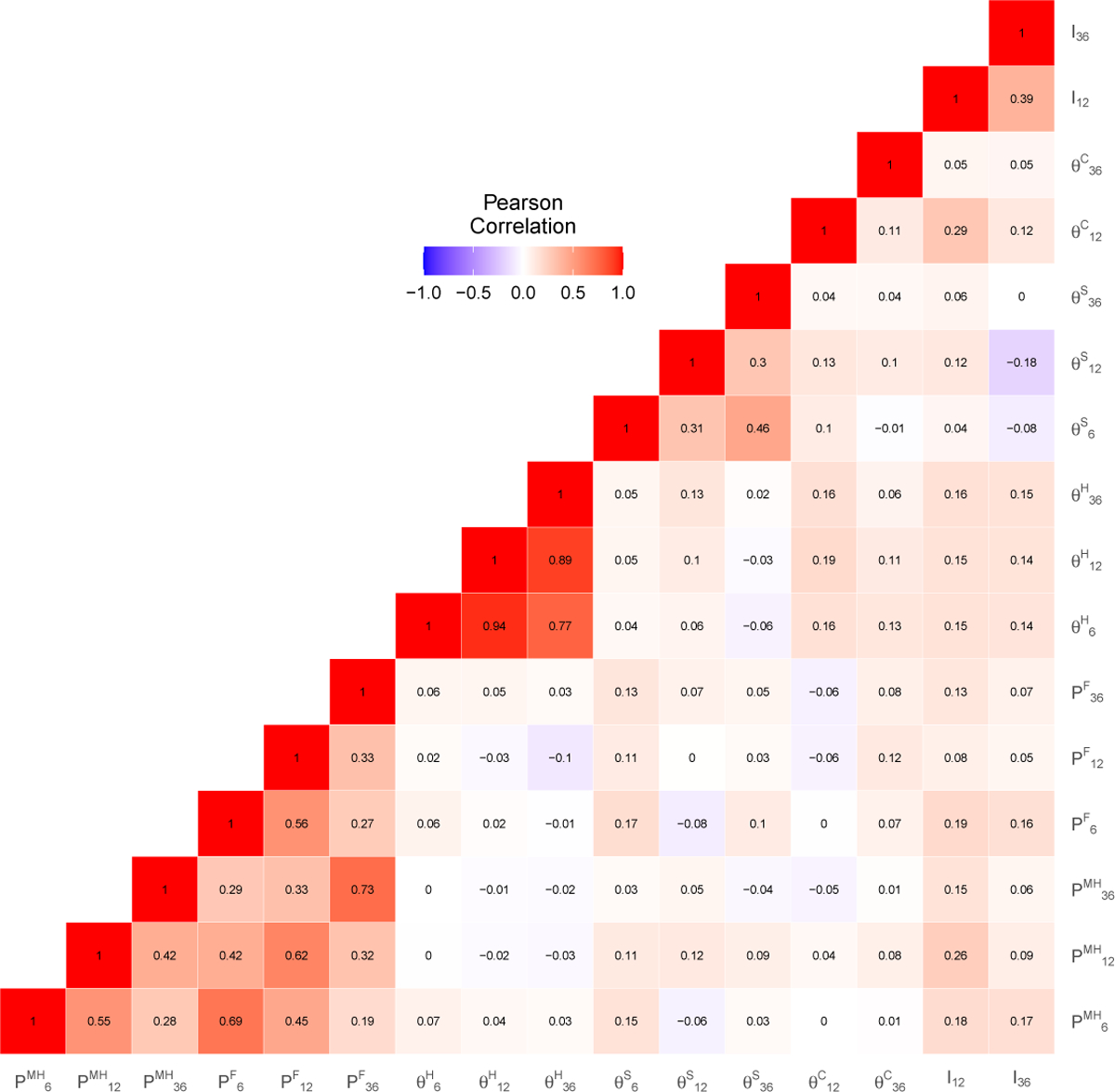

Table 4:

Estimates of the Production Function and Input Equations II

| Socioemotional skills (36m) (1) |

Physical health (36m) (2) |

Cognition (36m) (3) |

Parental investment (36m) (4) |

Maternal mental health (36m) (5) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SE skills (12m) | 0.183*** (0.037) |

0.033* (0.020) |

0.012 (0.023) |

−0.075** (0.031) |

0.024 (0.032) |

| physical health (12m) | 0.026 (0.042) |

1.048*** (0.026) |

0.046** (0.023) |

0.067** (0.029) |

−0.023 (0.038) |

| cognition (12m) | 0.012 (0.038) |

−0.017 (0.022) |

0.059*** (0.022) |

0.029 (0.033) |

−0.057** (0.027) |

| mother mental health (12m) | 0.083 (0.097) |

0.045 (0.050) |

−0.074 (0.059) |

0.202*** (0.075) |

0.287*** (0.067) |

| mother functioning (12m) | −0.063 (0.049) |

−0.049* (0.028) |

0.065** (0.033) |

−0.010 (0.049) |

0.094* (0.054) |

| investment (36m) | 0.158** (0.071) |

0.001 (0.039) |

0.092** (0.039) |

0.150* (0.077) |

|

| Interactions | |||||

| mother MH (12m) × treat | 0.057 (0.118) |

−0.055 (0.056) |

0.060 (0.066) |

−0.152* (0.084) |

−0.028 (0.096) |

| mother MH (12m) × nondep. | −0.001 (0.112) |

0.003 (0.046) |

−0.005 (0.068) |

−0.074 (0.086) |

−0.100 (0.093) |

| investment (36m) × treat | −0.214* (0.112) |

0.034 (0.053) |

−0.086 (0.059) |

−0.117 (0.080) |

|

| investment (36m) × nondep. | 0.017 (0.101) |

−0.048 (0.045) |

−0.008 (0.051) |

−0.158** (0.071) |

|

| Total factor productivity (TFP) | |||||

| TFP | 0.564 (2.503) |

−1.546** (0.702) |

1.960** (0.949) |

1.918 (1.380) |

1.344 (1.332) |

| TFP × treat | −0.031 (0.079) |

−0.160*** (0.043) |

0.022 (0.036) |

0.133** (0.059) |

0.113 (0.071) |

| TFP × nondep. | −0.164 (0.123) |

0.039 (0.060) |

−0.046 (0.072) |

0.120 (0.093) |

−0.035 (0.104) |

| Baseline controls | |||||

| SES assets | −0.014 (0.015) |

−0.004 (0.012) |

−0.001 (0.011) |

0.053*** (0.019) |

−0.004 (0.018) |

| mother’s education (years) | −0.006 (0.006) |

0.006 (0.004) |

0.013*** (0.004) |

0.016*** (0.005) |

0.010* (0.005) |

| husband’s education (years) | 0.009 (0.007) |

−0.003 (0.004) |

0.008 (0.006) |

0.031*** (0.008) |

0.012* (0.012) |

| Observations | 881 | 881 | 881 | 881 | 881 |

| R2 | 0.404 | 0.839 | 0.302 | 0.311 | 0.331 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.363 | 0.827 | 0.253 | 0.266 | 0.285 |

SE= socioemotional skills, MH=mental health. Dependent variables are child outcomes and parental investment and maternal mental health factors at 36 months postpartum. Independent variables include an indicator of treatment status (control, treatment, nondepressed), child and maternal factors at 12 months, parental investment factor at 36 months. Maternal mental health and parental investment are interacted with the treatment status. All estimations control for baseline characteristics including mother’s baseline age, weight, height, waist circumference and blood pressure, family structure, grandmother being resident, total adults in the household, people per room, number of living children (split by gender), whether the index child is the first child, parental education levels, asset based SES index, life events checklist score, interviewer fixed effect, union council fixed effect, days from baseline and child age in days. Robust and clustered standard errors at the cluster level are reported in paranthesis.

Note:

p<0.1;

p<0.05;

p<0.01

We now discuss the role of maternal mental health and parental investment across the three groups of women (control, treatment, and baseline non-depressed), initially for outcomes at 12 months of age, Table 3, and then for outcomes at 36 months, Table 4. First consider column 1 of Table 3 for child socioemotional (SE) skills, as this is where we find intervention effects at 12 months (see Figure 2). In the control group of women who were depressed in pregnancy but received no intervention (top panel), maternal mental health at 6 months is a significant predictor of socioemotional skills at 12 months, consistent with Figure 5b.22 Parental investment at 12 months is positive but imprecisely determined.

The intervention modifies the shape of the production function in two significant dimensions (second panel, interactions). We see a positive coefficient on the interaction of TFP with treat and a negative coefficient on the interaction of maternal mental health with treat. A higher TFP in the treatment group indicated that the intercept and the whole production function have shifted up: the outcome is higher for each level of input. The negative interaction with maternal mental health tells us that the slope of the curve describing how the outcome varies with maternal MH is flatter in the treated group than in the control group. This is consistent with decreasing returns to improvements in mental health (Figure 5b) as well as a larger effect of the intervention on the socioemotional skills of children whose mothers did not recover from depression (Figure 5c).

Both the positive TFP shift and the shallowing of the slope of the relationship with maternal MH that we see in the treated group are also evident in the group of mothers who were non-depressed at baseline. Thus, in line with expectations, the intervention moved the outcomes of children and mothers with prenatal depression closer to the outcomes of children and mothers who were not depressed during pregnancy. Put differently, the intervention bridges the “depression gap” in the production function, morphing the technology of skill formation for depressed mothers to look more like that for women who did not suffer depression during pregnancy.

We now summarize the main results for other outcomes at 12 months of age, in columns 2–5 of Table 3. In the control group, maternal mental health at 6 months is predictive not only of socioemotional skills but also of cognitive skills and physical health: it is significantly associated with child development across domains. Maternal functioning at 6 months has no direct relationship with child development above and beyond other inputs, such as maternal mental health and parental investments, but it raises parental investment. Parental investments at this early age are not predictive of any domain of child development, but they are related to maternal mental health. It is also no-table that parental education and assets have a significant positive impact on parental investments but, conditional on investment, have no direct impact on child outcomes.

Intervention effects are reported in the second and third panels of Table 3. The intervention raises TFP in the production of physical (but not cognitive) development. It attenuates the relationship between maternal MH and cognition, and it strengthens the return to investments when the outcome is cognition. Once again, the direction of effects in the intervention arm is the same as the direction of effects among the group of mothers not depressed in pregnancy.

Now consider estimates for the production function for child skills at 36 months (Table 4). The estimates for the control group show that maternal mental health at 12 months has only small and statistically insignificant associations with child skills at 36 months, but is predictive of higher parental investments. In turn, parental investment at 36 months predicts higher socioemotional and cognitive skills at 36 months, conditional on maternal MH. Intervention effects at 36 months are also most evident for the investment outcome. The pattern is similar to that observed for skills outcomes at 12 months: TFP is higher, and there is an attenuation of the relationship between maternal MH and parental investment. The only significant intervention effect in the production functions for child skills indicates lower TFP in the production of the physical health of the child, for which we have no clear explanation.

Mirroring our reduced form analysis of treatment effects and following recent trends in the literature focusing on socioemotional skills and mental health (Moroni et al., 2019), we split the sample by gender and estimate the technology of skill formation separately for boys and girls. Appendix Tables A36–A37 suggest that the overall pattern of production function results is similar across child genders. If anything, maternal mental health seems to be more predictive of parenting for mothers of girls, although statistical power is limited for this comparison.

5.2. Discussion

Taking stock, the intervention changes both the level of the inputs and their associations with the outcomes (returns). First, it improves maternal mental health (at 6, 12, and 36 months). This is an input to the production function, being directly associated with an improvement in child skills at 12 months while, at 36 months, it is associated with improved child skills through increasing parental investment. Second, the intervention changes the shape of the production function, changing both its intercept (TFP) and its slope (the productivity of specific inputs—maternal health at 12 months, and parental investment at 36 months).