Many men would agree with Woody Allen’s implication that their penis is their favourite organ. This is certainly apparent to clinicians who deal with human sexuality and who see men whose penises are not behaving as they should. However, professionals can become as fixated on this organ as their patients and forget that it has a multiplicity of connections within the man’s mind and body—and, indeed, outside it. Our concepts of sexual problems and their assessment and treatment must reflect this fact if we are to effectively deliver the help that our patients desperately seek.

“My brain? It’s my second favourite organ.” Woody Allen, Sleeper, 1993

It is convenient to consider sexual problems as dichotomies (organic or psychogenic, primary or secondary, male or female), but such distinctions are often inaccurate and unhelpful. The presence of a problem is a subjective perception influenced by many factors. However, there is no doubt that for most men sexuality is a highly rated aspect of their quality of life.

Physical causes of male sexual problems

Peripheral vascular disease

Diabetes

Multiple sclerosis

Spinal injury

Spinal or brain surgery

Hormonal or endocrine abnormalities

Pelvic disease, trauma, or surgery

Genital abnormality, disease, or surgery

Consumption of alcohol, tobacco, and prescribed and illicit drugs

From various studies in the general population and primary care it seems that 15-20% of men describe some sort of sexual problem. The proportion of men who actually seek help is unknown. For many men this is difficult, and their presentation may be hesitant or disguised in terms of another complaint. The first and crucial step in managing a sexual problem is to engage the patient with an interested and sympathetic attitude. Problems are more likely to occur in men who are known to their general practitioner because of physical or mental illness or because of their advancing age; in such cases an established good relationship will facilitate communication.

Comorbidity

Given the evolutionary importance of sexual activity, it is not surprising that it can be adversely affected by almost all forms of ill health. However, we must remember that we can add to this sexual morbidity by the treatments we dispense. Iatrogenic problems are common and are important, if only because they affect cooperation with treatments.

Commonly used drugs associated with male sexual dysfunctions

Antihypertensives (such as thiazide diuretics, β blockers)

Antidepressants (all but a few such as nefazodone and mirtazepine)

Antipsychotics (all, but some are less likely such as olanzapine)

Anticonvulsants and mood stabilisers (carbamazepine, lithium)

H2 antagonists (cimetidine)

Lipid lowering drugs (clofibrate)

Others—cytotoxic drugs, opiates, digoxin, disulfiram, antiandrogens

Physical morbidity

In the general population the perceived association between physical health and sexual functioning is weak, but in the clinical setting the relation is more obvious and several disorders have been linked with sexual problems.

Managing drug induced side effects

Delay dosing until after sexual intercourse

Take “drug holidays” at suitable times, such as weekends

Reduce dose

Substitute with alternative treatment

Withdraw drug

Reduce effects with adjunctive agents

Side effects of treatment

Invasive procedures, such as abdominal, pelvic, or genital surgery can lead to erectile dysfunction, usually by damage to peripheral nerves. Postcoital pain may be experienced after vasectomy because of formation of cysts around the severed vas.

Many drugs have been associated with male sexual dysfunctions.

Psychiatric morbidity

All forms of psychiatric disorder can lead to disturbances in sexuality, either directly, through common effects on the central nervous system, or indirectly, as a result of social or psychological changes and drugs’ side effects. Depression, anxiety, and schizophrenia are commonly associated with reduced desire and arousal. Mania and hypomania can be accompanied by hypersexuality. However, the assumption, common even among professionals, that people with severe mental illnesses do not need or want satisfying sexual relationships is unfounded.

Recreational drugs

Alcohol is commonly believed to enhance sexuality. Although this is probably true for some men, its inhibitory effects on arousal and its often undesirable behavioural effects are well documented. Increasing levels of consumption are associated with proportionate increases in erectile dysfunction, with 50-80% of alcoholics experiencing impotence. Effects are both immediate and long term, as chronic alcoholics show lowered testosterone concentrations caused by disturbance of the hypothalamic-pituitary axis.

Tobacco consumption also produces immediate and long term effects on erections that are sometimes dramatic.1 Giving up smoking often leads to improvement. It is surprising that impotence is not cited more often as a persuasive reason for giving up smoking.

Effects of ageing

Ageing is characterised by physiological, pathological, behavioural, and psychosocial changes that can all affect sexual functioning, and it is difficult to disentangle their individual effects. There has been relatively little research into sexuality in old age, but available surveys show that some form of sexual activity usually continues until the end of life. For example, in a sample of people aged 80-102, 62% of the men and 30% of the women were still having sexual intercourse.2 Clinicians tend to ignore this aspect of the lives of elderly people, who themselves can find sexual problems very difficult to talk about. However, it is wrong to assume that little can be done about problems at this stage in life, as many causes are potentially reversible.3

Age related factors leading to sexual dysfunction

Physical disease—peripheral vascular, diabetic neuropathy

Psychiatric illness—dementia, depression

Lack of willing partner, opportunity, or privacy

Lifestyle factors—smoking, alcohol consumption, physical inactivity, boredom, loneliness

These factors are common and potentially reversible

Sexual changes associated with ageing

Decreased frequency of activity

Decreased arousal in response to psychological stimuli

Decreased tactile sensitivity of penis

Increased refractory period after orgasm

Increased rates of erectile dysfunction with age

Decreased rates of premature ejaculation

Psychological factors

Research into factors affecting sexual arousal in men has revealed interesting and clinically relevant observations, and the emerging picture is consistent though far from complete.4

Anxiety

Anxiety does not have a consistent effect on arousal. It reduces arousal in men with sexual problems but increases arousal in men without. Anxiety related to thoughts of sexual failure have an adverse effect, whereas anxiety associated with novelty or threat is more likely to increase arousal. Men seem to be more susceptible to the effects of anxiety on arousal than women.

Mood

Mood has similarly variable effects. For example, the affective response of men with erectile dysfunction to erotic stimuli is negative, but for men without erectile dysfunction it is positive. Depressed mood causes reduced arousal, thus establishing vicious circles.

Cognitions

Cognitions (thoughts) have a profound effect on sexual response and modulate the effects of mood and anxiety.5 Patterns of thinking arise from a complex variety of interacting sources such as a person’s cultural, religious, social, educational, and family backgrounds, genetic factors, and past experiences. Understanding these sources in any individual is interesting, but the work of cognitive psychologists shows that changing undesirable cognitions is achieved by helping the person to identify and challenge these thoughts (this is the basis for cognitive therapy, which is used to treat a wide range of mental health problems).

Thoughts and erectile dysfunction

| Men without erectile | Men with erectile | |

| dysfunction | dysfunction | |

| Estimate of quality of own erection | Accurate | Underestimate |

| Erectile response to distraction | Decrease | Increase |

| Erectile response to sexual demands | Increase | Decrease |

Ways of challenging unhelpful thoughts

Am I confusing belief with fact?

Is this belief a helpful way to think about the issue?

What evidence is there that this belief is true?

Would other people see things in this way?

Would I apply the same belief to other people in the same circumstances?

Am I ignoring evidence that this belief may not be true?

Am I falling into the trap of overgeneralising or overstating the issue?

A common example of unhelpful thoughts, particularly in young men, is concern about the size and shape of their penis. Such concerns can lead to considerable difficulties in initiating or maintaining sexual relationships and other sexual problems. Helping men to challenge such concerns by providing information and in other ways is usually very helpful.

Nature of sexual stimulus

Men show more attraction to visual sexual stimuli, whereas women are more attracted to auditory and written material, and in particular stimuli associated with a context of a loving and positive relationship. However, studies of arousal in response to these stimuli show little difference between the sexes.

Relationship

Men with sexual dysfunction are less likely to perceive the quality of their general relationship as relevant to their sexual problems than are their partners or women with sexual problems. Paradoxically, they are more likely to describe improvement in their general relationship in response to successful treatment for sexual problems.

“The Coolidge effect” is so named after the story of Mrs Coolidge, wife of President Coolidge, who on a visit to a farm was impressed by a cockerel’s sexual prowess until she was informed that his performance of “a dozen times a day” was with a different hen each time

Habituation

Although it is politically controversial, there is considerable evidence that habituation affects responsiveness to sexual stimuli and to partners. Novelty in both increases arousal (the “Coolidge effect”) and seems to be more attractive to men than to women.

Dominance and self esteem

Self esteem and social success seem to have a sexually enhancing effect, possibly more so in men than women, and there is evidence that women are more attracted to more powerful or socially dominant men.

Life events

Major events such as bereavements, redundancy, accidents, traumatic experiences, or operations can precipitate changes in sexual behaviour or functioning. Problems that develop in this way can become chronic, particularly if predisposing factors were present. In some cases health professionals can anticipate such problems and have a responsibility to discuss this with their patients—for example, giving information and reassurance about the effects of vasectomy or prostatectomy. Anxieties about the risks of sexual activity after myocardial infarction are common, and advice and reassurance must be given to patients without waiting for them to ask (see previous chapter).

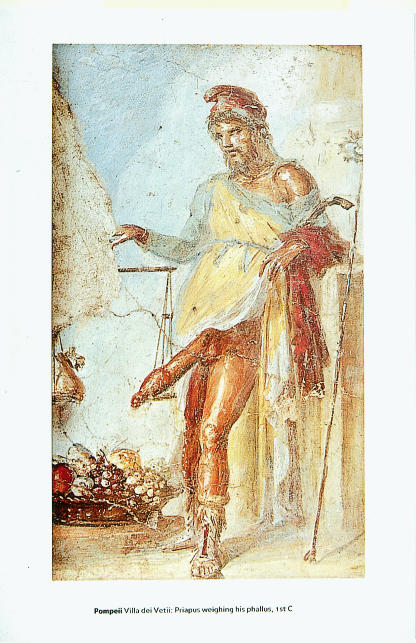

Figure.

For many men, a properly functioning penis is fundamental to their self esteem. (Priapus weighing his penis—from a fresco in the Villa dei Vetii, Pompeii, first century)

Figure.

Both alcohol consumption and smoking are associated with erectile dysfunction (“Oh, tender youth, where are you?” from The Tower of Love (1920s) by Reunier)

Figure.

Concern about the size and shape of the penis is a common problem, particularly in young men. (The Lacedaemonian Ambassadors (1896) by Aubrey Beardsley)

Figure.

High self esteem and social success seem to enhance a man’s sexual function and his attractiveness to women. (A prince enjoying five women from the Kama Sutra (1800), from the Rajput School, Kotah, Rajasthan)

Acknowledgments

1 Hirshkowitz M, Karacan I, Howell J, Arcasoy M, Williams RL. Nocturnal penile tumescence in cigarette smokers with dysfunction. Urology 1992;39:101-7. 2 Bretschneider JG, McCoy NL. Sexual interest and behaviour in healthy 80-102 year olds. Arch Sex Behav 1988;17:109-29. 3 Feldman HA, Goldstein I, Hatzichristou DG, Krane RJ, McKinlay JB. Impotence and its medical and psychosocial correlates: results of the Massachusetts male ageing study. J Urol 1994;151:54-61. 4 Rosen RC, Leiblum SR. Treatment of sexual disorders in the 1990s: an integrated approach. J Consult Clin Psychol 1995;63:877-90. 5 Cranston-Cuebas MA, Barlow DH. Cognitive and affective contributions to sexual functioning. Annu Rev Sex Res 1990;1:119-61.

The lithograph by Reunier and the painting from the Kama Sutra are reproduced with permission of the Bridgeman Art Library.

Footnotes

Alain Gregoire is consultant psychiatrist at the Old Manor Hospital, Salisbury, and senior lecturer at the University of Southampton.

The ABC of sexual health is edited by John Tomlinson, physician at the Men’s Health Clinic, Winchester and London Bridge Hospital, and formerly general practitioner in Alton and honorary senior lecturer in primary care at the University of Southampton.

Alain Gregoire is consultant psychiatrist at the Old Manor Hospital, Salisbury, and honorary senior lecturer at the University of Southampton.

The ABC of sexual health is edited by John Tomlinson, physician at the Men’s Health Clinic, Winchester and London Bridge Hospital, and formerly general practitioner in Alton and honorary senior lecturer in primary care at the University of Southampton.