Abstract

Polymorphisms in the prion protein (PrP) gene are associated with phenotypic expression differences of transmissible spongiform encephalopathies in animals and humans. In sheep, at least 10 different mutually exclusive polymorphisms are present in PrP. In this study, we determined the efficiency of the in vitro formation of protease-resistant PrP of nine sheep PrP allelic variants in order to gauge the relative susceptibility of sheep for scrapie. No detectable spontaneous protease-resistant PrP formation occurred under the cell-free conditions used. All nine host-encoded cellular PrP (PrPC) variants had distinct conversion efficiencies induced by PrPSc isolated from sheep with three different homozygous PrP genotypes. In general, PrP allelic variants with polymorphisms at either codon 136 (Ala to Val) or codon 141 (Leu to Phe) and phylogenetic wild-type sheep PrPC converted with highest efficiency to protease-resistant forms, which indicates a linkage with a high susceptibility of sheep for scrapie. PrPC variants with polymorphisms at codons 171 (Gln to Arg), 154 (Arg to His), and to a minor extent 112 (Met to Thr) converted with low efficiency to protease-resistant isoforms. This finding indicates a linkage of these alleles with a reduced susceptibility or resistance for scrapie. In addition, PrPSc with the codon 171 (Gln-to-His) polymorphism is the first variant reported to induce higher conversion efficiencies with heterologous rather than homologous PrP variants. The results of this study strengthen our views on polymorphism barriers and have further implications for scrapie control programs by breeding strategies.

Scrapie is a fatal and infectious neurodegenerating disease occurring in sheep and goats. The disease belongs to the group of transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSEs) or prion diseases found in humans and animals. Creutzfeldt-Jacob disease, Gerstmann-Sträussler-Scheinker syndrome, and fatal familial insomnia in humans and bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) in cattle also belong to this group. Prion diseases are characterized by the accumulation of an “infectious” abnormal protease-resistant isoform (PrPSc) of the host-encoded cellular prion protein (PrPC) in tissues of the central nervous system. Although the exact origin and nature of the causative agent remain unknown, it is thought to transmit and replicate by protein only (16). PrPSc molecules form the major, if not the only, component of the agent transmitting the disease (28).

Several polymorphisms in the open reading frame of PrP are associated with differences in phenotypic expression of prion diseases such as incubation period, pathology, and clinical signs. For PrP of sheep, 10 mutually exclusive amino acid polymorphisms at positions 112 (Met to Thr), 136 (Ala to Val), 137 (Met to Thr), 138 (Ser to Asn), 141 (Leu to Phe), 151 (Arg to Cys), 154 (Arg to His), 171 (Gln to Arg or Gln to His), and 211 (Arg to Gln) have been described (Table 1) (1, 2, 6, 12, 13, 20, 25, 33). The polymorphisms at codons 136, 171, and to a lesser extent 154 occur frequently, while the polymorphisms at codons 137, 211, and to a lesser extent 112 are rare. The allelic variant PrPVRQ (amino acids at positions 136 [Val], 154 [Arg], and 171 [Gln] are indicated in superscript by single-letter amino acid codes; polymorphisms at other codons are indicated separately [Table 1]) is significantly associated with a high susceptibility to scrapie and short survival times of scrapie-affected sheep of many different breeds (6, 9, 14, 20, 21, 25). In contrast, the allelic variant PrPARR is significantly associated with resistance to natural and experimental infections with scrapie and BSE in probably all sheep breeds (1, 6, 9, 14, 15, 20). In breeds where the PrPVRQ allele is rare or absent (for instance, the Suffolk breed), the phylogenetic wild-type (wt) PrPARQ allelic variant is associated with increased scrapie susceptibility but with lower penetrance than found for the PrPVRQ allele (21, 34). Little is known about the association of the allelic variants PrPT112ARQ, PrPAT137RQ, PrPAHQ, PrPARH, and PrPARQQ211 with susceptibility to scrapie.

TABLE 1.

Allelic variants of sheep PrP

| Variant designation

|

Polymorphic amino acid residue at position:

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allele | Proteina | 112 | 136 | 137 | 138 | 141 | 151 | 154 | 171 | 211 |

| PrPARQ | PrPC_wt and PrPSc_wt | M | A | M | S | L | R | R | Q | R |

| PrPT112ARQ | PrPC_112T | T | A | M | S | L | R | R | Q | R |

| PrPVRQ | PrPC_136V and PrPSc_136V | M | V | M | S | L | R | R | Q | R |

| PrPAT137RQ | PrPC_137T | M | A | T | S | L | R | R | Q | R |

| PrPAN138RQb | PrPC_138N | M | A | M | N | L | R | R | Q | R |

| PrPAF141RQ | PrPC_141F | M | A | M | S | F | R | R | Q | R |

| PrPAC151RQb | PrPC_151C | M | A | M | S | L | C | R | Q | R |

| PrPAHQ | PrPC_154H | M | A | M | S | L | R | H | Q | R |

| PrPARR | PrPC_171R | M | A | M | S | L | R | R | R | R |

| PrPARH | PrPC_171H and PrPSc_171H | M | A | M | S | L | R | R | H | R |

| PrPARQQ211 | PrPC_211Q | M | A | M | S | L | R | R | Q | Q |

PrPARQ has been designated as phylogenetic wt since all polymorphic variants can be derived from this variant by a single nucleotide or amino acid change.

Polymorphisms published during manuscript preparation and therefore excluded from this study.

The mechanisms by which the different allelic variants contribute to susceptibility to scrapie are not completely understood. From genetic studies, it can be deduced that naturally occurring variants of PrP, including those associated with a high risk for scrapie, probably cannot induce the spontaneous development of scrapie in sheep (5, 18, 19) as has been found for inherited prion diseases. Furthermore, it has been shown that the scrapie susceptibility-linked polymorphisms at codon 136 and 171 can modulate the efficiency of the cell-free conversion of sheep PrPC to protease-resistant forms (PrP-res [protease-resistant PrP for which no linkage with infectivity has been demonstrated]) induced by PrPSc (4). In this cell-free system, sheep PrPC_VQ (=PrPC_136V) and PrPC_AQ (=PrPC_wt) are efficiently converted to PrP-res by the homologous PrPSc (PrPSc_VQ/VQ [=PrPSc_136V] and PrPSc_AQ/AQ [=PrPSc_wt], respectively). In contrast PrPC_AR (=PrPC_171R) is poorly converted to PrP-res by PrPSc (4, 29). Also, other biological aspects of TSE diseases such as species barriers, polymorphism barriers, and the nongenetic propagation of prion strain phenotypes are reflected in the specificities of PrP conversion reactions in this cell-free system (3, 4, 24, 29). Therefore, the system may be used to gauge the potential in vivo transmissibility of TSEs and to predict the susceptibility of hosts for TSEs (3, 24, 29).

In this study, we used this cell-free system to determine the relative conversion efficiencies of the various sheep PrP allelic variants by PrPSc isolated from sheep with different PrP genotypes. Based on the observed conversion efficiencies, we tried to gauge the linkage between nine natural occurring variants of PrP (PrPARQ and eight polymorphic variants [Table 1]) and the susceptibility of sheep for scrapie, and to a minor extent we tried to gauge the transmissibility of scrapie between sheep. This relative scrapie susceptibility profile may allow further development and/or justification of specific sheep breeding programs. It may also provide insight into structurally important residues involved in modulation of the conversion efficiencies of PrPC to PrPSc, and it may reveal important sites in the PrP molecule to target in the development of potential therapeutics. The effect of each of the eight polymorphisms on the cell-free conversion efficiencies and the predicted in vivo modulation of scrapie phenotype will be discussed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

PrP constructs and expression.

The sheep PrP allelic variants PrPARQ, PrPVRQ, and PrPARR were cloned, expressed, and characterized as described before (4). The full open reading frames of the sheep allelic variants PrPAT137RQ, PrPAF141RQ, PrPAHQ, PrPARH, and PrPARQQ211 were cloned by PCR amplification and proofread by DNA sequencing essentially as described by Bossers et al. (6). Sheep PrP allelic variant PrPT112ARQ, which was not readily available, was constructed by site-directed mutagenesis using standard methods. After subcloning all of the different sheep PrP allelic variants (EMBL accession no. AJ000679 to AJ000681 and AJ000734 to AJ000739) to eukaryotic expression vector pECV7 (4), the PrP constructs were transfected to N2a/H (Hubrechts, Utrecht, The Netherlands) eukaryotic cells as described elsewhere (4). Single-cell clones that expressed each PrP allelic variant were analyzed for expression by immunoperoxidase monolayer assay and radioimmunoprecipitation (4). The best PrPC-expressing single-cell clones were selected and/or stored for further labeling experiments. To monitor the stability and validity of the expressed sheep PrP sequences, the genomically integrated sequences were proofread by PCR amplification and subsequent analyzed by denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis after several rounds of subculturing the single cell clones (6).

Radiolabeling and purification PrPC.

Single-cell clones that expressed the different sheep PrPC variants were subcultured 2 days before labeling and labeled at near confluency as described previously (4, 7). Briefly, cells were starved for 30 to 60 min in culture medium containing only 1/10 of the normal concentration of methionine and 7.5 μg of tunicamycin D per ml. After labeling for 90 to 120 min at 37°C with at least 1 mCi of [35S]methionine-[35S]cysteine Tran35S-label (ICN) per 25-cm2 flask, the cells were lysed (0.5% Triton X-100, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 5 mM Tris-Cl [pH 7.4] [4°C], 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA) on ice in the presence of protease inhibitors (0.1 mM Pefabloc SC, 0.5 μg of leupeptin per ml, 0.7 μg of pepstatin per ml, 1 μg of aprotinin per ml). Proteins were precipitated from detergent lysates by 4 volumes of methanol at −20°C and subsequently sonicated in DLPC buffer (0.05 M Tris-HCl [pH 8.2], 0.15 M NaCl, 2% [wt/vol], N-laurylsarcosine, 0.4% [wt/vol] lecithin) containing the same protease inhibitor cocktail. 35S-PrPC was immunopurified by using antibody R521-7 (raised to sheep PrP peptide 94-107), which specifically reacts with sheep PrPC (4, 11a). Immunocomplexes were collected by using protein A-Sepharose, and bound 35S-labeled proteins were eluted in 0.1 M acetic acid (pH 2.8). If necessary, eluants were concentrated by vacuum evaporation and reconstituted in 50 mM citrate buffer pH 6.0 (G. J. Raymond, personal communication). Yield of radiolabeled PrPC was measured with a micro-β counter, and eluates were stored on ice until further use.

PrPSc purification and analysis.

PrPSc was isolated from randomly collected brain tissue (cerebrum) of five different PrPARQ/ARQ sheep, four different PrPVRQ/VRQ sheep, and one PrPARH/ARH sheep. All suffered from natural scrapie confirmed by immunohistochemistry. PrPSc was purified in the absence of protease inhibitors by ultracentrifugational pelleting from 15 g of Sarkosyl-homogenated brains (4, 8). After pelleting through a 20% sucrose cushion, the pellet was sonicated in 275 μl of phosphate-buffered saline containing 1% sulfobetaine (SB 3-14) and stored in portions at 4°C. After 1 h of digestion with 45 μg of protease K (PK) per ml at 37°C, yields of PrPSc were quantified by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) followed by SYPRO Orange (Molecular Probes) protein staining. Direct fluorescence within the 20- to 30-kDa region was determined with a STORM-840 (Molecular Dynamics) in comparison to the internal PK band and a standard dilution of bovine serum albumin. In addition, the relative amounts of PrPSc were quantified by Western blotting using antibody R521-7 (1:1,500), ECF fluorescence substrate (Amersham-Pharmacia Biotech), and the STORM-840. All isolates contained about 2 to 6 μg of PrPSc per g of brain. PrPSc yields from PrPARQ/ARQ sheep brain (3 to 6 μg/g) were almost always higher than yields from PrPVRQ/VRQ sheep brain (2 to 4 μg/g). PrPSc concentrations were equalized by further dilution in phosphate-buffered saline containing 1% SB 3-14. Isolates of PrPSc were stored at 4°C and briefly sonicated prior to use.

Cell-free conversion.

Approximately 0.9 μg of PrPSc per conversion reaction in siliconized tubes was partially denatured at a final concentration of 2.5 M guanidine HCl (Gdn-GdnHCl) (using 8 to 9 M Gdn-HCl in 50 mM sodium citrate) overnight at 37°C in the presence of protease inhibitors. The partially denatured PrPSc was subsequently added to a conversion mix containing about 10,000 cpm of nonglycosylated 35S-labeled PrPC and conversion buffer to give final concentrations of ≤1 M Gdn-HCl, 50 mM sodium citrate (pH 6.0), 1% N-laurylsarcosine, and 5 mM cetyl pyridinium chloride in a total volume of 34 μl or less. The use of nonglycosylated PrPC does not seem to alter species specificity, strain specificity, and polymorphism barrier specificity (3, 4, 24, 29). Reactions were mixed regularly and incubated for 2.5 days at 37°C. After incubation, each reaction volume was increased to 100 μl by addition of Tris-NaCl (50 mM Tris-Cl [pH 7.5], 150 mM NaCl) and split 1:10. The 9/10 fraction was digested with 35 μg of PK per ml for 1 h at 37°C, and thereafter PK was inactivated by adding Pefabloc SC on ice. The proteins in both fractions, minus (1/10) and plus (9/10) PK, were precipitated for at least 2 h with methanol in the presence of 20 μg of thyroglobulin as a carrier. Pellets were sonicated and boiled in 4% β-mercapthoethanol–4 M urea containing Laemmli sample buffer and analyzed by SDS-PAGE on a 14% gel (Novex). Percentage of conversion was determined by measuring radiolabel in specific regions of the gels (input PrPC, 25 to 27 kDa; conversion products, 20 to 22 kDa), using for the initial experiments exposures of X-ray film and for later experiments phosphorimaging (STORM-840). Percent conversion was calculated as conversion signal/start signal × 10% × 100/90. At least two or more independent conversion reactions were performed from each different PrP variant. Normalization was performed within each set of conversions (nine PrPC variants with one PrPSc type) in comparison to the homologous conversion in that particular set. The significance of differences between PrPC conversion efficiencies was calculated by the linear mixed model regression method.

RESULTS

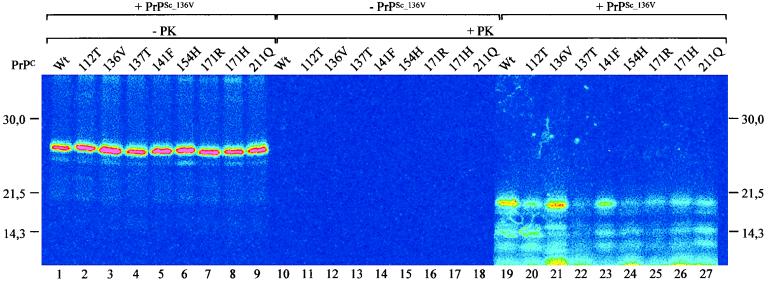

The nine different naturally occurring sheep PrPC variants could be readily detected after labeling, immunoprecipitation, and SDS-PAGE by phosphorimaging (Fig. 1, lanes 1 to 9). Due to the absence of glycosylation, a uniform product with a molecular mass of about 26 kDa was present in all lanes, indicating that apart from the single amino acid changes, no differences could be observed with regard to processing and/or partial endogenous proteolysis. In addition, also at the cell culture level, we detected no (microscopic) differences between the nine different variants in biosynthesis and localization of PrPC in immunoperoxidase monolayer assays. The nine radiolabeled PrPC variants revealed no PrP-res formation after incubation under cell-free conversion conditions without addition of exogenous PrPSc (Fig. 1, lanes 10 to 18). This finding indicates that under these in vitro conditions, no detectable spontaneous formation of PrP-res occurs, which coincides with the requirement of exogenous agent for natural scrapie development (5, 18, 19). In contrast, if partially denatured PrPSc is added to the conversion reaction, readily detectable PrP-res formation occurs with the specific shift in molecular mass of about 6 kDa (Fig. 1, lanes 19 to 27).

FIG. 1.

Phosphorimage of an SDS-polyacrylamide gel (indicated in pseudo-intensity staining) showing cell-free conversion reactions of nine different nonglycosylated sheep PrPC variants by sheep PrPSc_136V to PK-resistant forms. Lanes 1 to 9 show approximately 1/10 of the input of PrPC in the various conversion reactions. Incubation of these variants under cell-free conditions revealed no spontaneous PrP-res formation after PK digestion (lanes 10 to 18). Different amounts of PrP-res were formed upon addition of partially denatured exogenous PrPSc (lanes 19 to 27). PK digestion removes about 6 kDa from the N-terminal part of PrP when converted to protease-resistant forms (compare lanes 1 to 9 with lanes 19 to 27). Molecular mass markers (in kilodaltons) are indicated.

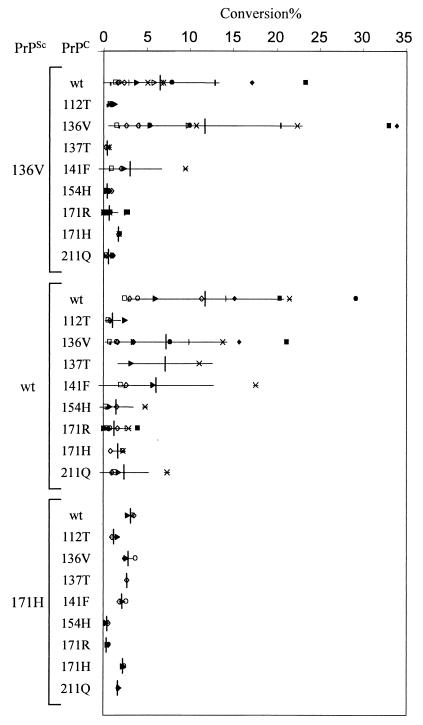

Three different PrPSc preparations, i.e., PrPSc_wt, PrPSc_136V, and PrPSc_171H, could be obtained from natural scrapie cases homozygous for PrP. Of several independent isolates, about 1 μg of PrPSc was partially denatured and subsequently renatured under conversion conditions in the presence of one of each of the nine different 35S-labeled PrPC molecules. After PK digestion, SDS-PAGE, and phosphorimaging, different amounts of PrP-res could be observed (Fig. 1, lanes 19 to 27). These sets of nine conversion experiments were repeated several times with PrPSc preparations isolated from different sheep brains, except for PrPSc_171H, of which the various isolates were obtained from the single homozygous PrPARH/ PrPARH scrapie case available worldwide. The data show that for unknown reasons, the conversion efficiencies between sets vary enormously (Fig. 2) independent of PrPSc isolate. However, the relative conversion efficiencies of the nine allelic variants induced by either PrPSc_wt, PrPSc_136V, or PrPSc_171H in multiple and independent experiments were very similar. For example, in all PrPSc_136V-induced conversion sets, the PrPC_136V allelic variant was always converted with highest efficiency, PrPC_wt was converted with reduced efficiency (Pdifferent_136V = 0.06), and PrPC_171R was converted almost not at all (Pdifferent_wt < 0.01). Therefore, we normalized the data for each set of nine conversion experiments to the homologous conversion reaction within that set, usually the strongest conversion reaction (Fig. 3).

FIG. 2.

Scattergraph of individual percentages of PrPC conversion to protease-resistant forms. Each set of conversions (nine PrPC variants induced by a single PrPSc type performed at the same time) is indicated by a single marker. The nine different sheep PrPC variants are converted with different efficiencies by either PrPSc_136V, PrPSc_wt, or PrPSc_171H. Mean conversion percentages (±standard deviation) are indicated.

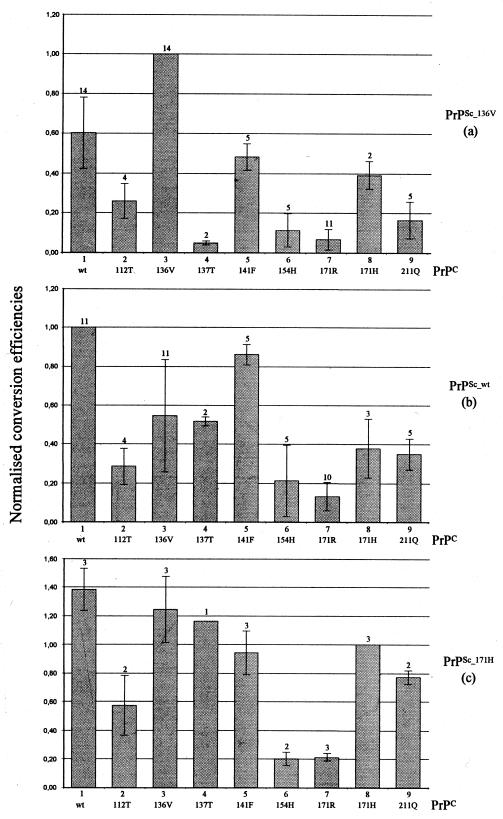

FIG. 3.

Sets of conversions (a plus b plus c), defined as all nine different PrPC variants incubated with one type of PrPSc, were normalized to the homologous conversion reactions. Mean normalized conversion efficiencies (±standard deviation) and the number of independent conversion reactions of each PrPC variant are indicated.

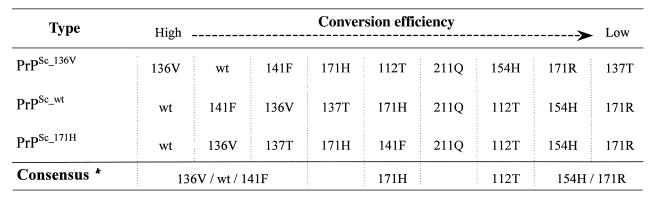

Within each conversion set, remarkable differences in the convertibility of PrPC into PrP-res are visible. In each PrPSc set, a trend in decreasing convertibility can be observed. The order of this trend in the three different sets is summarized in Fig. 4. From these three different PrPSc sets, we created a consensus in which the rare allelic variants PrPAT137RQ and PrPARQQ211 were excluded (Fig. 4). This consensus indicates the relative order in which these allelic variants are predicted to be linked to susceptibility for scrapie. The most efficient converting variants by each of the three types of PrPSc were PrPC_136V, PrPC_wt, and PrPC_141F, while PrPC_112T, PrPC_154H, and PrPC_171R converted with low efficiency. The variants PrPC_171H and PrPC_211Q converted with intermediate efficiency. Some remarkable differences between the first two PrPSc sets exist (compare Fig. 3a and b). One observed difference is the switch in convertibility of PrPC_136V and PrPC_wt with homologous and heterologous PrPSc (Fig. 3a and b, bars 1 and 3). Another point of interest is the relatively high conversion rate of PrPC_141F, which has conversion properties similar to those of PrPC_wt (Fig. 3a and b, bars 1 and 5; Pdifferent_wt = 0.77). The PrPC_137T variant behaves like PrPC_136V in PrPSc_wt- and PrPSc_171H-induced reactions (Fig. 3b and c, bars 3 and 4; Pdifferent_136V = 0.88 and 0.80, respectively), while this variant is inconvertible by PrPSc_136V (Fig. 3a, bar 4; Pdifferent_wt < 0.01 while Pdifferent_171R = 0.37).

FIG. 4.

Relative conversion efficiencies of the various sheep PrPC variants by each PrPSc. PrPC allelic variants are indicated by their single amino acid polymorphisms and ranked within each type of PrPSc in order of decreased conversion efficiency. *, virtually absent PrP allelic variants in vivo; PrPAT137RQ and PrPARQQ211 were excluded.

The smaller data set of the convertibility of various PrPC variants by PrPSc_171H shows also a shift in the relative conversion efficiencies of the nine PrP variants. Due to the limited availability of PrPSc_171H, only one to three data points could be generated for each PrPC variant. The results show, however, that the heterologous variants PrPC_wt, PrPC_136V, and PrPC_137T have higher conversion efficiencies with PrPSc_171H than the homologous PrPC_171H variant itself (Fig. 3, compare bars 1, 3, and 4 with bar 8 in each panel). More importantly, the convertibility of the PrPC_154H and PrPC_171R variants in the PrPSc_171H set remained low (Fig. 3c, bars 6 and 7).

DISCUSSION

In a previous study (4), we demonstrated that the conversion efficiencies of three sheep PrP variants (PrPC_136V, PrPC_wt, and PrPC_171R) reflected their linkage with scrapie susceptibility. In this study, we measured the conversion efficiencies of nine different PrP allelic variants with three different types of PrPSc. Based on these results, we tried to gauge the linkage of PrP alleles with relative susceptibility for scrapie. Of these nine allelic variants, those with polymorphisms at either codon 112, 137, 141, 154, 171, or 211 have not been significantly associated with a particular scrapie phenotype.

The nine different natural variants of sheep PrPC, incubated with different types of PrPSc, converted to PrP-res in vitro with different efficiencies. The most efficient converting PrPC variants were PrPC_136V, PrPC_wt, and PrPC_141F. The conversion efficiencies of variants PrPC_154H, PrPC_171R, and to a minor extent PrPC_112T were consistently low in all reactions induced with the different types of PrPSc. From the perspective of breeding strategies, of great interest are the low-convertible variants PrPC_154H and PrPC_171R for positive selection and the variants PrPC_136V, PrPC_wt, and PrPC_141F for negative selection. The presence in the same flock of several PrP variants which are linked to resistance may turn out to be safer in scrapie control programs based on breeding strategies and may contribute to maintaining a more genetically diverse sheep population.

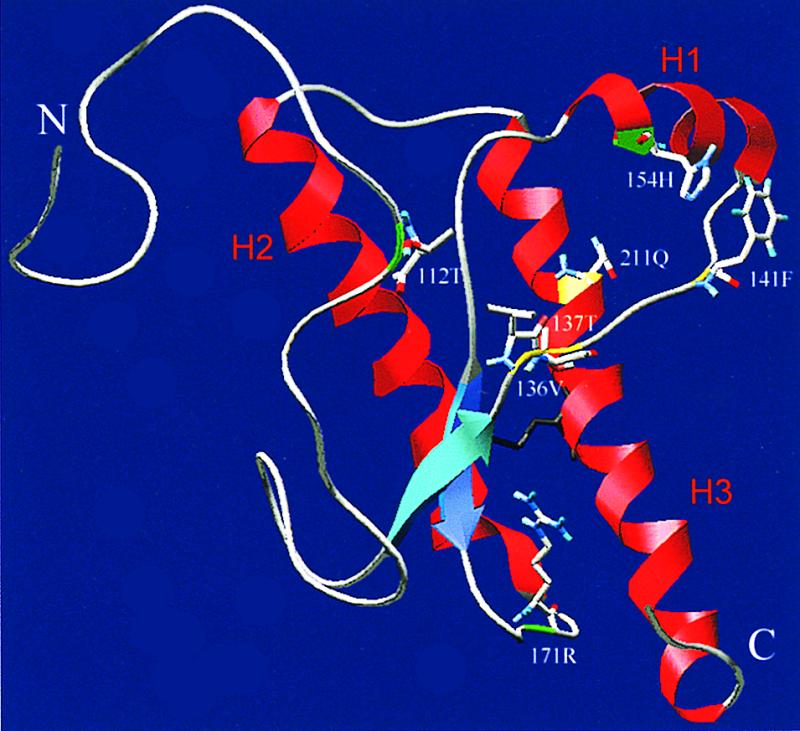

The conversion efficiencies of the allelic variants PrPC_136V, PrPC_wt, and PrPC_171R are consistent with the earlier in vitro observations of a smaller conversion data set (4). Although the PrPSc_wt in the latter study was less potent in inducing conversions of PrPC_wt and PrPC_136V, a comparable but less drastic switch in the convertibility of PrPC_wt and PrPC_136V was observed if conversions were induced by either PrPSc_wt or PrPSc_136V. The codon 112 polymorphism Met to Thr reduces the convertibility of PrP compared to PrPC_wt in conversion reactions induced by different types of PrPSc (P = <0.04). This reduced convertibility is consistent with observations that this allelic variant in homozygous form is found only in healthy sheep (at low frequency). Only a few heterozygous PrPVRQ/PrPT112ARQ or PrPARQ/PrPT112ARQ scrapie-infected sheep of the Ile-de-France or Japanese Suffolk breed have been described (22, 25). In these cases, the other alleles are probably dominant and result in scrapie development. In the theoretical three-dimensional structure of sheep PrP, this polymorphism is located in the highly flexible N-terminal region (Fig. 5). The larger side chain of Met, the polarity of Thr, or the shorter hydrogen bond between amino acids at codons 110 and 112 may influence the stability of PrPC and/or the interaction with PrPSc since both side chains are directed toward the potential interaction site.

FIG. 5.

Three-dimensional representation of all polymorphic residues in sheep PrP. Sheep PrP fragment (amino acids 93 to 234) was modeled by using SwissModel (27) and the three-dimensional structures (PDB) of recombinant hamster PrP (2PrP) and mouse PrP (1AG2) as templates. The N terminus (N), C terminus (C), α-helices 1 to 3, and the separate polymorphic positions are indicated.

The allelic variant PrPC_137T demonstrates conversion properties similar to those of PrPC_136V in PrPSc_wt- and PrPSc_171H-induced conversion reactions (Pdifferent_136V = 0.88 and 0.80, respectively). In PrPSc_136V-induced conversion reactions, however, the codon 137 polymorphism results in inconvertibility (Pdifferent_wt < 0.01; Pdifferent_171R = 0.37). Probably the neighboring polymorphisms at codons 136 and 137 interfere with the potential interaction site between PrPC and PrPSc (Fig. 5). No in vivo data for this allelic variant are available since the allele is rare (only one healthy but culled sheep has been found to have this allele [6]). This allele is therefore irrelevant for breeding strategies and was excluded from the consensus linkage with scrapie susceptibility in Fig. 4.

The polymorphism Phe at codon 141 (PrPC_141F) had minor reduction effects on the convertibility to PrP-res, and this variant reacted in the same order of magnitude as PrPC_wt (Pdifferent_wt = 0.77). This seems to be consistent with observations that sheep having the PrPVRQ/PrPAF141RQ genotype have somewhat longer survival times than sheep having the PrPVRQ/PrPARQ genotype, while both have longer survival times than PrPVRQ/PrPVRQ sheep in a flock of Swifter sheep where PrPVRQ is linked to highest scrapie susceptibility and shortest survival times (6). Based on in vitro conversion efficiencies, the PrPAF141RQ allele is expected to be associated with high susceptibility in flocks where PrPARQ is associated with highest scrapie susceptibility. From the similar conversion efficiencies of PrPC_wt and PrPC_141F, but also from amino acid sequence comparisons between different species, the L141F polymorphism is expected to act fairly neutrally. In addition, L141M in hamster and mouse, L141V in brush-tailed possum, and L141I in human and gorilla are also found without any demonstrated linkage to TSEs, which indicates that some degree of evolutionary amino acid freedom at this position of the PrP is allowed. However, the neighboring polymorphism in goat PrP at codon 142 (Ile to Met) is associated with decreased susceptibility to experimental infections with scrapie and BSE (15), suggesting that the loop between β-sheet 1 and α-helix 1 (Fig. 5) is not without importance.

The observed low convertibility of the PrPC_154H variant confirms previous speculations that this variant might also induce a certain degree of resistance to scrapie development (Pdifferent_171R = 0.06, 0.15, and 0.71 for PrPSc_136V, PrPSc_wt, and PrPSc_171H, respectively). However, to our knowledge only two natural cases of scrapie in a PrPAHQ/PrPAHQ sheep have been found in the United Kingdom in a flock where PrPARQ is associated with highest susceptibility (M. Dawson, personal communication). This observation and the data for experimental challenge of sheep with the PrPAHQ allele show that this allele does not induce such an absolute resistance to TSEs as the PrPARR allele (10, 31). This seems to be consistent with the slightly increased in vitro conversion efficiencies of the PrPC_154H variant compared to the PrPC_171R variant in vitro (Pdifferent = 0.06). After intracerebral infections with the CH1641 scrapie isolate (predominant PrPSc_wt) or BSE, sheep with the PrPAHQ/PrPAHQ genotype, but not with the PrPARR/PrPARR genotype, developed scrapie with some unusual features (31). The 10-fold reduction in convertibility of PrPC_154H compared to PrPC_136V in the PrPSc_136V-induced reactions and the 5-fold reduction in convertibility of this PrPC_154H variant compared to PrPC_wt in the PrPSc_wt-induced reactions suggests that in vivo the PrPAHQ allele may induce more resistance in flocks where PrPVRQ is associated with highest scrapie susceptibility rather than in flocks where PrPARQ is associated with highest scrapie susceptibility. The codon 154 polymorphism is located in α-helix 1 (Fig. 5), and its charged side chain may interfere with the potential nucleation site between the two smaller β-sheets toward α-helix 1. In addition, this polymorphism induces a charge inversion comparable to that found in the resistant PrPC_171R variant, indicating that the two polymorphisms may destabilize the hydrophobic core and/or the dipolar character of PrP by similar mechanisms.

The allelic variant PrPC_171H has a significantly reduced convertibility compared to PrPC_wt in conversion reactions induced by PrPSc_wt and PrPSc_171H (Fig. 3, bars 1 and 8; P < 0.01 and P = 0.02, respectively). The codon 171 Gln-to-His polymorphism is found mainly in Texel and some smaller cross-breeds. Several scrapie sheep with the PrPVRQ/PrPARH genotype have been described (2), and thus far only a single scrapie-infected PrPARH/PrPARH sheep of the Dutch Zwartbles breed has been found (unpublished results). Based on the in vitro conversion data and observations that this allele in the homozygous PrPARH/PrPARH setting is almost absent in sheep with scrapie, it may be that the PrPARH allele introduces a certain degree of resistance to scrapie at least in a homozygous setting but has a more neutral role in heterozygous PrPARH genotypes.

The codon 211 polymorphism (Arg to Gln), located inside α-helix 3 (Fig. 5), reduces convertibility compared to the PrPC_wt variant (P < 0.01). Polymorphisms at almost the same location in human PrP are all associated with spontaneous Creutzfeldt-Jacob disease or Gerstmann-Sträussler-Scheinkersyndrome (polymorphic codons 211 Arg to His, 213 Val to Ile, 215 Gln to Pro, or 220 Gln to Arg [sheep PrP numbering]) (17, 26, 30, 35). Under the cell-free conditions used, however, no detectable spontaneous PrP-res formation occurred in the PrPC_211Q reaction (Fig. 1, lane 18). Although only a single (culled) sheep with this PrPARQQ211 allele has been found (2), this polymorphism is found as a common polymorphism in goats (H. M. Schatzl, unpublished results), and its introduction in sheep therefore might actually have its origin in goats. Since goats and sheep have identical wt PrP sequences, it is predicted that this polymorphism is associated with reduced susceptibility in goats as well.

Only three different types of PrPSc could be isolated from sheep homozygous for PrPARQ, PrPVRQ, and PrPARH with natural scrapie. Since PrPSc could not be obtained from sheep homozygous for one of the other six PrP genotypes, no in vitro conversion data could be generated for these PrPSc types. Nevertheless, PrPSc from other homozygous types of PrPSc like PrPSc_141F or PrPSc_154H are of great interest. Conversion reactions using, for instance, PrPSc_154H may elucidate whether allelic variants linked to resistance remain inconvertible even when induced with homologous PrPSc. Such conversion reactions are important for the justification of future scrapie control programs which introduce TSE-resistant PrP genotypes. The set of nine conversion reactions induced by PrPSc_171H indicate that the most efficient reaction is not always the homologous one (Fig. 3c).

Since only one scrapie sheep with the PrPARH/PrPARH genotype was found, limited PrPSc was available for in vitro conversions. Although the data set for PrPSc_171H is limited, some interesting observations could be made. The relative conversion efficiencies of the various PrPC variants by PrPSc_171H reflected most of the features of reactions induced with the PrPSc_wt or PrPSc_136V, for instance, the reduced convertibility of the PrPC_154H and PrPC_171R variants (P < 0.01), the reduced convertibility of the PrPC_112T variant (P < 0.01), the comparable characteristics of PrPC_141F and PrPC_wt, and the overall high convertibility of the PrPC_wt and PrPC_136V variants. A rather unusual feature, however, is the relatively high convertibility of PrPC_wt, PrPC_136V and to lesser extent PrPC_141F compared to the homologous PrPC_171H variant (Fig. 3c, bars 1, 3, 5, and 8). This PrPSc_171H variant seems to be the first ever described variant of PrPSc inducing higher conversion efficiencies in heterologous PrPC variants than in homologous variants. The molecular mechanism underlying this effect is still unclear, but it might be that as an intrinsic property, PrPC_171H has less capability to convert to protease-resistant PrP. This PrPSc_171H conversion set therefore emphasizes that some polymorphic PrPC variants (like PrPC_171R and PrPC_154H) are more or less prone to convert than others, independent of PrPSc type.

Some conversion reactions showed a large variation in conversion efficiency between independent PrPSc isolates (Fig. 3a, bar 1; Fig. 3b, bars 3 and 6). This variation might be linked to PrPSc isolate quality and/or it might be linked (hypothetically) to the PrP allele which in that particular flock is associated with high scrapie susceptibility. For example, PrPSc_wt isolated from PrPARQ/PrPARQ sheep residing in a flock of sheep in which the PrPVRQ allele is associated with high scrapie susceptibility might be different from PrPSc_wt isolated from sheep in a flock in which the PrPARQ allele is associated with highest scrapie susceptibility. These structural differences between PrPSc isolates may cause shifted conversion profiles between the various PrPC variants. For instance, PrPSc_wt from a PrPVRQ background might convert PrPC_136V better and PrPC_wt less than PrPSc_wt from a PrPARQ background. This might indicate that if scrapie develops in sheep residing in a flock in which a different PrP allele is linked to highest risk of scrapie, the scrapie agent has overcome the polymorphism barrier (defined as a single amino acid mismatch between PrPC and PrPSc reducing the conversion efficiency) but may not be completely adapted to the PrP genotype of the new host, and thus the isolated PrPSc might still be carrying “PrPVRQ information.” Adaptation effects in strains when transmitted to different species have been theoretically predicted by numerical integration to require at least two or three passages for stabilization (23). Data on the isolation, transmission, and characterization of the CH1641 scrapie isolate indicate that these adaptation effects may also occur in vivo (11, 14). If these adaptation effects between the different PrP genotypes in vivo indeed occur, then it becomes even more important to know the PrP alleles in the direct environment of sheep before assessing their risk for scrapie development. Whether this hypothesis is true needs further investigation.

All of the different sheep PrP polymorphisms (except codon 211) are located in, or their side chains are directed to, the potential interaction site between PrPC and PrPSc (Fig. 5). This interface, which has been predicted to be located between the two smaller β-sheets toward α-helix 1, might interact very specifically in the process of self recognition between PrPSc and PrPC (PrPC_136V is most efficiently converted by PrPSc_136V, while PrPC_wt is most efficiently converted by PrPSc_wt). The polymorphism at codon 136 (Ala or Val), which influences convertibility or polymorphisms like Pro to Leu in human PrP at codon 102 (32), may modulate the interaction (recognition) between PrPC and PrPSc. Such a recognition site might be a potential location in PrP for interference with PrPSc formation or TSE replication by targeting antibodies or synthetic peptides.

In summary, this study has found a clear effect of different polymorphisms in sheep PrPC and to a lesser extent in sheep PrPSc on the in vitro convertibility of PrPC to protease-resistant isoforms. The conversion data indicate that sheep with the PrPVRQ, PrPARQ, and PrPAF141RQ alleles are at high risk for scrapie development. The alleles of PrPAHQ, PrPARR, and to minor extent PrPT112ARQ seem to be linked to resistance to scrapie. Therefore, these alleles seem to be most suitable for introducing genetic resistance to scrapie by breeding strategies using positive selection for PrPARR and PrPAHQ and negative selection for PrPVRQ, PrPARQ, and PrPAF141RQ. It should be mentioned, however, that in vivo other factors such as dose, strain of TSE, route of infection, and efficiency of delivery are likely to be important in determining scrapie susceptibility and transmissibility. Future studies including BSE, sheep-passaged BSE, or PrPSc of other species may reveal which animals are most prone to carry or become infected with a cross-species TSE infection.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank L. J. M. van Keulen and coworkers for collecting of sheep materials and confirmation of the scrapie cases, and we thank W. Buist for help with the statistical analysis.

REFERENCES

- 1.Belt P B, Muileman I H, Schreuder B E, Bos-de Ruijter J, Gielkens A L, Smits M A. Identification of five allelic variants of the sheep PrP gene and their association with natural scrapie. J Gen Virol. 1995;76:509–517. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-76-3-509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Belt P B G M, Bossers A, Schreuder B E C, Smits M A. PrP allelic variants associated with natural scrapie. In: Gibbs C J Jr, editor. Bovine spongiform encephalopathy; the BSE dilemma. New York, N.Y: Springer; 1996. pp. 294–305. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bessen R A, Kocisko D A, Raymond G J, Nandan S, Lansbury P T, Caughey B. Non-genetic propagation of strain-specific properties of scrapie prion protein. Nature. 1995;375:698–700. doi: 10.1038/375698a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bossers A, Belt P B G M, Raymond G J, Caughey B, de Vries R, Smits M A. Scrapie susceptibility-linked polymorphisms modulate the in vitro conversion of sheep prion protein to protease-resistant forms. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:4931–4936. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.10.4931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bossers A, Harders F L, Smits M A. PrP genotype frequencies of the most dominant sheep breed in a country free from scrapie. Arch Virol. 1999;144:829–834. doi: 10.1007/s007050050548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bossers A, Schreuder B E, Muileman I H, Belt P B, Smits M A. PrP genotype contributes to determining survival times of sheep with natural scrapie. J Gen Virol. 1996;77:2669–2673. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-77-10-2669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caughey B, Kocisko D A, Raymond G J, Lansbury P T., Jr Aggregates of scrapie-associated prion protein induce the cell-free conversion of protease-sensitive prion protein to the protease-resistant state. Chem Biol. 1995;2:807–817. doi: 10.1016/1074-5521(95)90087-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caughey B W, Dong A, Bhat K S, Ernst D, Hayes S F, Caughey W S. Secondary structure analysis of the scrapie-associated protein PrP 27-30 in water by infrared spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 1991;30:7672–7680. doi: 10.1021/bi00245a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clouscard C, Beaudry P, Elsen J M, Milan D, Dussaucy M, Bounneau C, Schelcher F, Chatelain J, Launay J M, Laplanche J L. Different allelic effects of the codons 136 and 171 of the prion protein gene in sheep with natural scrapie. J Gen Virol. 1995;76:2097–2101. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-76-8-2097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Foster J D, Bruce M, McConnell I, Chree A, Fraser H. Detection of BSE infectivity in brain and spleen of experimentally infected sheep. Vet Rec. 1996;138:546–548. doi: 10.1136/vr.138.22.546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Foster J D, Dickinson A G. The unusual properties of CH1641, a sheep-passaged isolate of scrapie. Vet Rec. 1988;123:5–8. doi: 10.1136/vr.123.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11a.Garssen, G. J., L. J. M. van Keulen, C. F. Farquhar, M. A. Smits, J. G. Jacobs, A. Bossers, R. H. Meloen, and J. P. M. Langeveld. Application of three anti-PrP peptide sera including staining of tonsils and brainstem of sheep with scrapie. Micros. Res. Techniques, in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Goldmann W, Hunter N, Benson G, Foster J D, Hope J. Different scrapie-associated fibril proteins (PrP) are encoded by lines of sheep selected for different alleles of the Sip gene. J Gen Virol. 1991;72:2411–2417. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-72-10-2411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldmann W, Hunter N, Foster J D, Salbaum J M, Beyreuther K, Hope J. Two alleles of a neural protein gene linked to scrapie in sheep. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:2476–2480. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.7.2476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldmann W, Hunter N, Smith G, Foster J, Hope J. PrP genotype and agent effects in scrapie: change in allelic interaction with different isolates of agent in sheep, a natural host of scrapie. J Gen Virol. 1994;75:989–995. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-75-5-989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldmann W, Martin T, Foster J, Hughes S, Smith G, Hughes K, Dawson M, Hunter N. Novel polymorphisms in the caprine PrP gene: a codon 142 mutation associated with scrapie incubation period. J Gen Virol. 1996;77:2885–2891. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-77-11-2885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Griffith J S. Self-replication and scrapie. Nature. 1967;215:1043–1044. doi: 10.1038/2151043a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hsiao K, Dloughy S R, Farlow M R, Cass C, Da Costa M, Conneally P M, Hodes M E, Ghetti B, Prusiner S B. Mutant prion proteins in Gerstmann-Sträussler-Scheinker disease with neurofibrillary tangles. Nat Genet. 1992;1:68–71. doi: 10.1038/ng0492-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hunter N, Cairns D. Scrapie-free Merino and Poll Dorset sheep from Australia and New Zealand have normal frequencies of scrapie-susceptible PrP genotypes. J Gen Virol. 1998;79:2079–2082. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-79-8-2079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hunter N, Cairns D, Foster J D, Smith G, Goldmann W, Donnelly K. Is scrapie solely a genetic disease? Nature. 1997;386:137. doi: 10.1038/386137a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hunter N, Foster J D, Goldmann W, Stear M J, Hope J, Bostock C. Natural scrapie in a closed flock of Cheviot sheep occurs only in specific PrP genotypes. Arch Virol. 1996;141:809–824. doi: 10.1007/BF01718157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hunter N, Goldmann W, Smith G, Hope J. The association of a codon 136 PrP gene variant with the occurrence of natural scrapie. Arch Virol. 1994;137:171–177. doi: 10.1007/BF01311184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ikeda T, Horiuchi M, Ishiguro N, Muramatsu Y, Kai-Uwe G D, Shinagawa M. Amino acid polymorphisms of PrP with reference to onset of scrapie in Suffolk and Corriedale sheep in Japan. J Gen Virol. 1995;76:2577–2581. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-76-10-2577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kellershohn N, Laurent M. Species barrier in prion diseases: a kinetic interpretation based on the conformational adaptation of the prion protein. Biochem J. 1998;334:539–545. doi: 10.1042/bj3340539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kocisko D A, Priola S A, Raymond G J, Chesebro B, Lansbury P T, Jr, Caughey B. Species specificity in the cell-free conversion of prion protein to protease-resistant forms: a model for the scrapie species barrier. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:3923–3927. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.9.3923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Laplanche J L, Chatelain J, Westaway D, Thomas S, Dussaucy M, Brugere-Picoux J, Launay J M. PrP polymorphisms associated with natural scrapie discovered by denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis. Genomics. 1993;15:30–37. doi: 10.1006/geno.1993.1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mastrianni J A, Iannicola C, Myers R M, DeArmond S, Prusiner S B. Mutation of the prion protein gene at codon 208 in familial Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Neurology. 1996;47:1305–1312. doi: 10.1212/wnl.47.5.1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peitsch M C. ProMod and Swiss-Model: Internet-based tools for automated comparative protein modelling. Biochem Soc Trans. 1996;24:274–279. doi: 10.1042/bst0240274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Prusiner S B. Novel proteinaceous infectious particles cause scrapie. Science. 1982;216:136–144. doi: 10.1126/science.6801762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Raymond G J, Hope J, Kocisko D A, Priola S A, Raymond L D, Bossers A, Ironside J, Will R G, Chen S G, Petersen R B, Gambetti P, Rubenstein R, Smits M A, Lansbury P T, Jr, Caughey B. Molecular assessment of the potential transmissibilities of BSE and scrapie to humans. Nature. 1997;388:285–288. doi: 10.1038/40876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ripoll L, Laplanche J L, Salzmann M, Jouvet A, Planques B, Dussaucy M, Chatelain J, Beaudry P, Launay J M. A new point mutation in the prion protein gene at codon 210 in Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Neurology. 1993;43:1934–1938. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.10.1934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Somerville R A, Birkett C R, Farquhar C F, Hunter N, Goldmann W, Dornan J, Grover D, Hennion R M, Percy C, Foster J, Jeffrey M. Immunodetection of PrPSc in spleens of some scrapie-infected sheep but not BSE-infected cows. J Gen Virol. 1997;78:2389–2396. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-78-9-2389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Telling G C, Haga T, Torchia M, Tremblay P, DeArmond S J, Prusiner S B. Interactions between wild-type and mutant prion proteins modulate neurodegeneration in transgenic mice. Genes Dev. 1996;10:1736–1750. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.14.1736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tranulis M A, Osland A, Bratberg B, Ulvund M J. Prion protein gene polymorphisms in sheep with natural scrapie and healthy controls in Norway. J Gen Virol. 1999;80:1073–1077. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-4-1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Westaway D, Zuliani V, Cooper C M, Da Costa M, Neuman S, Jenny A L, Detwiler L, Prusiner S B. Homozygosity for prion protein alleles encoding glutamine-171 renders sheep susceptible to natural scrapie. Genes Dev. 1994;8:959–969. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.8.959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Young K, Piccardo P, Kish S J, Ang L C, Dlouhy S, Ghetti B. Gerstmann-Straussler-Scheinker disease (GSS) with a mutation at protein (PrP) residue 212. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1998;57:518. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199810000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]