Short abstract

Understanding the extent to which prescription drug prices are higher in the United States than in other countries is useful when developing policies to address both growth in drug spending and the financial impact of prescription drugs on consumers. This study summarizes findings from comparisons of drug prices in the United States and other high-income countries based on 2022 data and presents results from various sensitivity analyses.

Keywords: Health Care Costs, Health Care Price Competition, Pharmaceutical Drugs

Abstract

Understanding the extent to which prescription drug prices are higher in the United States than in other countries—after accounting for differences in the volume and mix of drugs—is useful when developing and targeting policies to address both growth in drug spending and the financial impact of prescription drugs on consumers. This study summarizes findings from comparisons of drug prices in the United States and other high-income countries based on 2022 data and presents results for specific types of drugs, including brand-name originator drugs and unbranded generic drugs, and from sensitivity analyses.

Understanding the extent to which prescription drug prices are higher in the United States than in other countries—after accounting for differences in the volume and mix of drugs—is useful when developing and targeting policies to address both growth in drug spending and the financial impact of prescription drugs on consumers.

A prior RAND analysis compared 2018 manufacturer gross drug prices in the United States with those in 32 Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries using a price index approach.1 The earlier analysis reported results for all drugs combined, for specific categories of drugs, and under different methodological approaches. This study updates the main results from this earlier report using more recent data through 2022.2 It also includes new analyses focusing on price comparisons for biosimilars and changes in price comparison results over time.

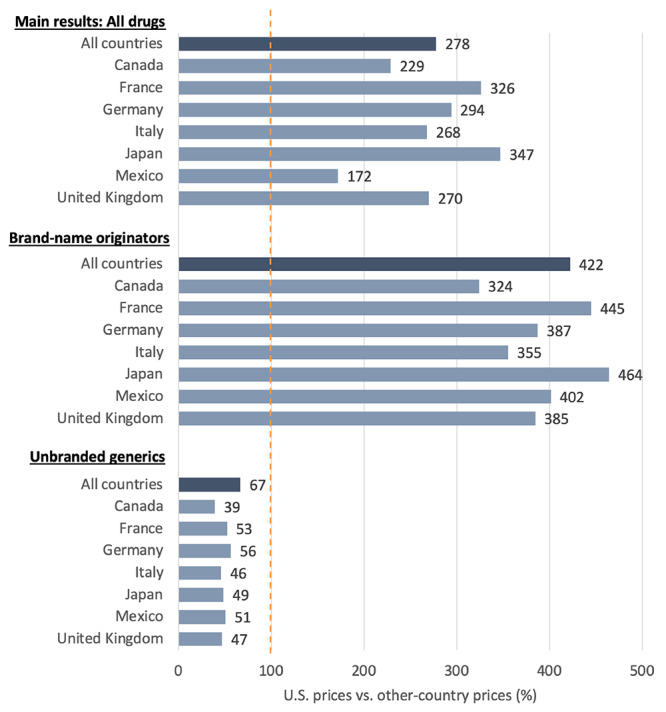

In brief, when analyzing data for all prescription drugs available in the United States and comparison countries, we found that U.S. manufacturer gross prices for drugs in 2022 were 278 percent of prices in the 33 OECD comparison countries combined. Put another way, prices in other countries were 36 percent—or a little more than one-third—of those in the United States.

These results stem from the combination of starkly different price comparison findings for brand-name versus generic drugs: U.S. prices for brand-name originator drugs were 422 percent of prices in comparison countries, while U.S. unbranded generics, which we found account for 90 percent of U.S. prescription volume, were on average cheaper at 67 percent of prices in comparison countries, where on average only 41 percent of prescription volume is for unbranded generics. U.S. prices for brand-name drugs remained 308 percent of prices in other countries even after adjustments to account for rebates paid by drug companies to U.S. payers and their pharmacy benefit managers.

These high-level findings from the current study are consistent with results from the prior analysis using 2018 data.3 Overall, the gap between U.S. and other countries’ prices widened slightly between the two analyses because of faster growth in U.S. prices, a change in U.S. drug mix, a change in the overlap of drugs sold in both the United States and other countries, or a combination of factors.

Study Approach

We used 2022 IQVIA MIDAS data to calculate price indexes comparing prescription drug prices in the United States with those in 33 OECD comparison countries.4 For our main results, we used presentation-level data (that is, data with separate records for each combination of active ingredient, formulation, and dosage strength) for all prescription drugs in the IQVIA MIDAS dataset.5 We then compared prices between the United States and individual OECD comparison countries bilaterally, using as many presentations overlapping between the United States and the other markets.6 Separately, we compared U.S. prices with those in all other countries in our data aggregated together as a summary measure. We used U.S. volume weights (that is, the share of total volume accounted for by each presentation) to calculate price indexes because of our interest in price differences from a U.S. policy perspective.

IQVIA MIDAS sales and volume estimates are projected from IQVIA's audits of standardized list prices and manufacturer, wholesaler, and other invoices; they do not reflect net prices realized by the manufacturers. These data are designed to support country-level trend and pattern analyses, but they remain estimates. The MIDAS data used in this analysis were obtained under license from IQVIA. Our MIDAS extract was prepared on May 19, 2023. Price indexes greater than 100 indicate that U.S. prices are higher than those in the comparison country; indexes less than 100 indicate that U.S. prices are lower than those in the comparison country.

Gross Price Comparison Results

In 2022, U.S. prices across all drugs were 278 percent of prices in the 33 OECD comparison countries.7 Prices in the United States were higher than those in each individual comparison country (see Figure 1 for comparisons of U.S. prices with those in the G7 countries and Mexico). For example, U.S. prices were 229 percent of prices in Canada (or, alternatively, Canadian prices were 44 percent of U.S. prices). Across all 33 comparison countries, U.S. prices ranged from 172 percent of prices in Mexico to 1,028 percent of prices in Turkey.

Figure 1.

U.S. Manufacturer Gross Prescription Drug Prices as a Percentage of Prices in Selected Other Countries, All Drugs, 2022

SOURCE: Authors’ analysis of 2022 sales and volume data from IQVIA, “MIDAS,” webpage, undated (run date May 19, 2023).

NOTE: All countries refers to all 33 OECD comparison countries combined. Other countries’ prices are set to 100. Biologics were excluded from unbranded generics. Only some presentations sold in each country contribute to bilateral comparisons. Brand-name originators and Unbranded generics reflect IQVIA's assignment of drug products in individual countries.

The gap between U.S. prices and prices in other countries was larger for brand-name originator drugs. U.S. prices were 422 percent of prices of non-U.S. countries for these drugs. However, prices for unbranded generic drugs were generally lower in the United States than in other countries. U.S. prices were 67 percent of prices of non-U.S. countries for unbranded generics. We found that U.S. prices were higher than most comparison countries when combining data for all non-originator drugs, including unbranded generics and brand-name non-originator drugs.8

France and Japan generally have the lowest prices among the comparison countries for all drugs and for brand-name originator, biologics, and nonbiologic drugs separately. Canada, Germany, and the United Kingdom tend to have higher prices across each subset of drugs.

Our main findings—that U.S. gross prices are higher than those in comparison countries for all drugs and for brand-name originator drugs but lower for unbranded generic drugs—held through several additional sensitivity analyses related to how price indexes were calculated.

Addressing U.S. Gross-to-Net Discounts

One important limitation of our analysis is that we use manufacturer prices for the purposes of comparison, because net prices (that is, the prices realized by manufacturers after negotiated and other discounts are applied) are not released by the pharmaceutical companies. The magnitude of the difference between manufacturer gross and net prices is difficult to quantify across all drugs. Net prices reflect confidential rebates negotiated between manufacturers and plan sponsors (often through their pharmacy benefit managers) that vary depending on market conditions and negotiating leverage. Net prices also reflect Medicaid best price and rebate program provisions, discounts from the 340B prescription drug discount program that may or may not be applied as drugs are sold by manufacturers, and discounts from other sources. In cases in which net prices can be reliably estimated, the magnitude of gross-to-net reductions varies substantially across therapeutic classes.9

To assess how our results might change if net price information were available, we conducted a final set of sensitivity analyses in which we adjusted U.S. prices downward based on published estimates of the relative differences between manufacturer gross and net prices. The resulting U.S. prices remained substantially higher than prices in other countries—but with a smaller difference than in our main results. When adjusting prices for U.S. brand-name drugs dispensed through the retail channel downward by 37.2 percent,10 U.S. prices for brand-name drugs were 308 percent of prices in other countries (versus 422 percent in our main results).

Because of a lack of available estimates, we did not adjust prices in other countries downward to reflect increasingly common discounts on manufacturer prices.11 U.S. prices would appear relatively higher—that is, more in line with our main results—if we were able to also adjust for rebates and other discounts applied to manufacturer prices in other countries.

Building on prior findings, this update provides further evidence that gross manufacturer drug prices are higher in the United States than in comparison countries. Although we apply a single, market-wide adjustment to approximate rebates and other discounts applied to U.S. brand-name prices, we recognize gross-to-net margins vary substantially across drugs and therapeutic classes and that our estimates of U.S. net prices therefore incorporate substantial measurement error. We also recognize that resulting price indexes will understate differences between prices in the United States and other countries because they adjust only U.S. prices downward even though rebates and similar discounts are increasingly common in other countries.

Notes

Andrew W. Mulcahy, Christopher M. Whaley, Mahlet Gizaw, Daniel Schwam, Nathaniel Edenfield, and Alejandro Uriel Becerra-Ornelas, International Prescription Drug Price Comparisons: Current Empirical Estimates and Comparisons with Previous Studies, RAND Corporation, RR-2956-ASPEC, 2021b.

The prior analysis compared U.S. prices with those in 32 OECD countries. Colombia joined the OECD in April 2020, after the prior analysis was completed. Our main results in this updated study include Colombia. Costa Rica became an OECD member in May 2021 but is not included in this updated analysis because IQVIA's MIDAS data do not include Costa Rica as a separate market.

MIDAS is a registered trademark of IQVIA. This study does not reproduce any IQVIA MIDAS data directly.

To avoid outlier presentations from exerting undue influence on our overall results, we excluded a small number of observations with (1) very low volume or sales or a given country and presentation, or (2) extreme ratios of U.S. prices to other-country prices.

The share of volume and sales contributing to each analysis varied widely but was generally considerably less than 100 percent. For example, for the United States–Canada comparison, 72 and 63 percent of Canadian and U.S. volume and 84 and 71 percent of Canadian and U.S. sales, respectively, contributed to our analysis. Among the Group of Seven (G7) countries, Japan had the smallest overlap with the United States, with only 17 and 30 percent of Japanese and U.S. volume and 48 and 46 percent of Japanese and U.S. sales, respectively, contributing to our analyses. The overlap in drugs sold in the United States and Japan was much higher at the active ingredient level (rather than the presentation level) at nearly 60 percent of volume and 80 percent of sales. This finding motivated robustness checks wherein we calculated prices at the active ingredient rather than the presentation level.

The number of drug presentations included in each bilateral analysis varied given the overlap between U.S. and comparison country data. The analysis comparing U.S. prices with prices in all comparison countries combined used data from 4,690 presentations and 1,646 active ingredients.

Prices in the United States were exactly 100 percent of prices in all other countries combined when unbranded generics and brand-name non-originator drugs were combined. While drugs labeled in IQVIA MIDAS as “unbranded non-originator” drugs are primarily unbranded generics, drugs designated as brand-name non-originators are more diverse and include (1) multisource branded generics (generic drugs marketed under a brand name, which is common in some countries outside the United States but very rare in the United States) and (2) brand-name drugs approved in the United States via the 505(b)(2) regulatory approval pathway (such as EpiPen). Drugs in the second category are often non-originator drugs, but they might be priced and marketed as brand-name originator drugs.

Andrew W. Mulcahy, Daniel Schwam, Preethi Rao, Stephanie Rennane, and Kanaka Shetty, “Estimated Savings from International Reference Pricing for Prescription Drugs,” JAMA, Vol. 326, No. 17, 2021a.

We calculated the 37.2 percent as one minus the 2022 ratio of net to invoice prices measured across protected brand drugs from IQVIA Institute for Human Data Science, The Use of Medicines in the U.S. 2023: Usage and Spending Trends and Outlook to 2027, May 2, 2023.

Ulf Persson and Bengt Jönsson, “The End of the International Reference Pricing System?” Applied Health Economics and Health Policy, Vol. 14, No. 1, 2016.

This research was sponsored by the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation and conducted within the Payment, Cost, and Coverage Program within RAND Health Care.

References

- IQVIA Institute for Human Data Science The Use of Medicines in the U.S. 2023: Usage and Spending Trends and Outlook to 2027. May 2, 2023. , , .

- Mulcahy Andrew W., Schwam Daniel, Preethi Rao, Rennane Stephanie, Shetty Kanaka Estimated Savings from International Reference Pricing for Prescription Drugs JAMA 2021a;326(17) doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.13338. , “. ,” . , Vol. , No. , . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulcahy Andrew W., Whaley Christopher M., Gizaw Mahlet, Schwam Daniel, Edenfield Nathaniel, Becerra-Ornelas Alejandro Uriel . International Prescription Drug Price Comparisons: Current Empirical Estimates and Comparisons with Previous Studies. RAND Corporation; 2021b. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR2956.html , , , RR-2956-ASPEC, . As of August 1, 2023: [Google Scholar]

- Persson Ulf, Jönsson Bengt The End of the International Reference Pricing System? Applied Health Economics and Health Policy 2016;14(1) doi: 10.1007/s40258-015-0182-5. , “. ” . , Vol. , No. , . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]