Abstract

Purpose

Locoregionally advanced HPV+ oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (OPSCC) has excellent cure rates, although current treatment regimens are accompanied by acute and long-term toxicities. We designed a phase II de-escalation trial for patients with HPV+OPSCC to evaluate the feasibility of an upfront neck dissection to individualize definitive treatment selection to improve quality of life without compromising survival.

Methods

Patients with T1–3, N0–2 HPV+ OPSCC underwent an upfront neck dissection with primary tumor biopsy. Patients with a single lymph node less than six centimeters, with no extracapsular spread(ECS), and no primary site adverse features underwent transoral surgery (Arm A). Patients who had two or more positive lymph nodes with no ECS, or those with primary site adverse features were treated with radiation alone (Arm B). Patients who had ECS in any lymph node were treated with chemoradiation (Arm C). The primary endpoint was quality of life at 1 year compared to a matched historical control.

Results

Thirty-four patients were enrolled and underwent selective neck dissection. Based on pathologic characteristics, 14 patients were assigned to arm A, 10 patients to arm B, and 9 to arm C. A significant improvement was observed in HNQOL compared to historical controls (−2.6 vs −11.9, p=0.034). With a median follow-up of 37 months, the 3-year overall survival was 100% and estimated 3-year estimated progression free survival was 96% (95% CI: 76–99%).

Conclusion

A neck dissection driven treatment paradigm warrants further research as a de-intensification strategy.

Keywords: human papillomavirus, oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma, neck dissection, de-escalation

Introduction

HPV related oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (HPV+ OPSCC) is one of the few cancers increasing in incidence in the United States[1]. Due to the low adoption of the HPV vaccine this epidemic is expected to continue to progressively worsen through 2040[2]. For patients with locally advanced disease, excellent rates of cure are seen with multimodality therapy. Treatment, however, is accompanied by significant acute and long-term toxicities including dysphagia, velopharyngeal insufficiency, xerostomia, lymphedema, dental problems, osteoradionecrosis, and voice changes[3, 4]. Psychosocial treatment related effects also exist including body image disturbance and social isolation related to difficulty with eating in public [4–7]. The impact of these difficulties is often underestimated by providers[7] and is especially pertinent as this disease predominately effects younger patients(age 40–60). High cure rates amongst HPV+ patients, thus, results in a large survivor population affected by lifelong treatment related toxicities.

Efforts are underway to de-escalate therapy to improve quality of life for patients while maintaining cure rates. Several strategies for de-intensification are being studied, including alternative chemotherapeutics, decreased doses of radiation, and more recently incorporation of upfront surgery alone. Recent data support the role of upfront surgery for de-escalation in HPV related OPSCC[8–10]. ECOG 3311 confirmed the feasibility of using transoral robotic surgery (TORS) followed by adjuvant therapy, and demonstrated that decreasing radiation dose to 50 gray provides promise toward de-escalation. However, up to 30% of patients still received trimodal therapy, which leads to worse swallowing outcomes than single or dual modality therapy[8, 9, 11].

Although imaging can localize potentially involved lymph nodes, it does not accurately capture the number of involved lymph nodes and fails to predict microscopic features such as extracapsular spread(ECS)[12, 13]. Neck dissection is considered the gold standard for lymph node evaluation and is associated with minimal risk[14–16]. Taken together, an up-front neck dissection offers the opportunity to assess tumor behavior and tailor adjuvant therapy accordingly.

Therefore, we conducted a phase II trial for patients with T1–3, N0–2 HPV+ OPSCC to evaluate upfront selective neck dissection as a method to guide further treatment to improve quality of life in a novel treatment paradigm.

Materials and Methods

Patient Eligibility

Our phase II study was approved by the institutional review board at the University of Michigan Rogel Cancer Center(NCT02784288). All patients provided written informed consent. Inclusion criteria was as follows: 18 or older with pathologically confirmed, previously untreated, p16-positive OPSCC, clinical stage T1-T3 and N0-N2(AJCC 7), primary tumors deemed to be surgically resectable, ECOG performance status 0–2, have adequate pre-treatment laboratory criteria, and agree to use highly effective contraception per protocol.

Patients with clinical T4 and/or N3 disease, those with matted lymph nodes(defined radiologically as three abutting nodes with loss of an intervening fat plane), FNA evidence of squamous cell carcinoma involving 3 or more lymph nodes, or a biopsy of the primary site showing perineural or perivascular invasion were not eligible[17]. Additional exclusion criteria included prior head and neck radiation, documented evidence of distant metastases, New York Heart Association(NYHA) class 3 or 4 heart disease, unstable angina, history of myocardial infarction within 6 months prior to enrollment, or active infection.

Patients underwent a multidisciplinary examination by Otolaryngology, Radiation Oncology, and Medical Oncology and were presented at the multi-disciplinary head and neck tumor board for staging and treatment planning. Baseline testing included assessment of the primary tumor and regional disease, laboratory studies, and PET/CT. This study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board.

Upfront Selective Neck Dissection

Upon enrollment, patients underwent selective neck dissection and biopsies of the primary tumor. The levels of neck dissection were at the discretion of the treating surgeon(minimum II-IV). For tumors at or approaching midline, a bilateral neck dissection was performed at the discretion of tumor board recommendations and the treating surgeon. Ligation of the external carotid artery was performed at the time of neck dissection.

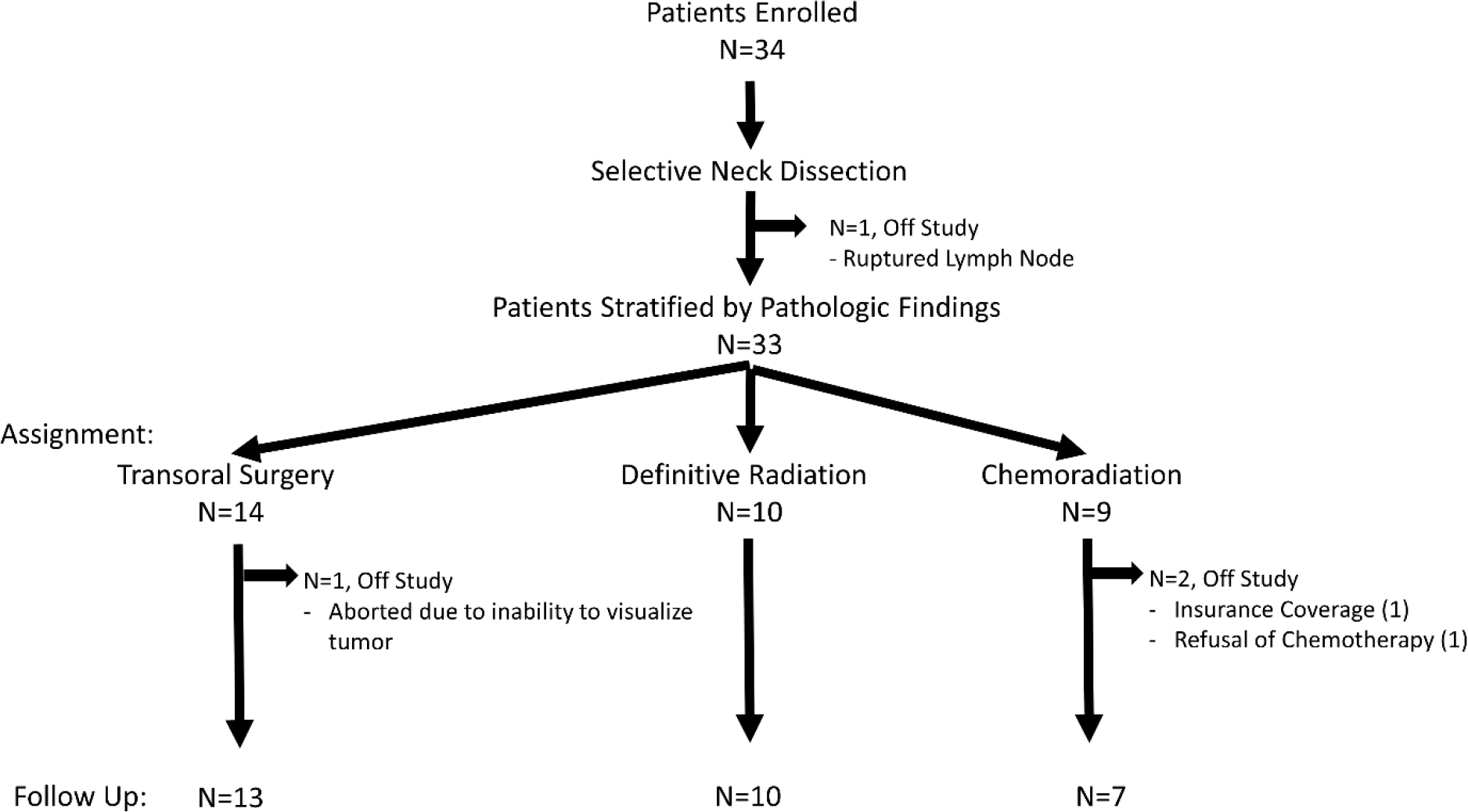

The neck dissection pathology was reviewed by a head and neck pathologist. Based on the findings, patients were stratified into one of three treatment groups(Figure 1). Per protocol, ECS was defined as any extension of metastatic carcinoma within the lymph node, through the capsule, and into the surrounding connective tissue. This included both microscopic ECS(≤ 1 mm) and macroscopic ECS(> 1 mm). Patients with a single lymph node that measured less than six centimeters, had no ECS, and had no perineural/perivascular invasion in the primary biopsy underwent transoral surgery of the primary site alone. Patients who had two or more positive nodes with no ECS, or who had perineural/perivascular invasion of the primary biopsy were treated with definitive radiation to the primary site and adjuvant radiation to the neck. Patients who had ECS in any number of lymph nodes were treated with definitive radiation to the primary site and adjuvant radiation to the neck with concurrent chemotherapy.

Figure 1:

CONSORT Diagram

Transoral Surgery

Surgery was performed using the DaVinci SI Robot(Intuitive, Sunnyvale CA), typically within 2 weeks of neck dissection. No patients underwent tracheostomy or PEG placement at the time of surgery. Frozen sections were used intraoperatively, and margins were taken from the primary surgical specimen and separately submitted margins at the discretion of the treating surgeon.

Radiation and Chemotherapy

All patients assigned radiation underwent standard head and neck simulation with 5-point mask and IV contrast unless contraindication. Radiation dosing was 70 Gy(35 fractions delivered 5 days/week) to the high-risk planning tumor volume(PTV70) including primary tumor gross disease, 66Gy to PTV66 to any positive margin or nodal level with pathologic extranodal extension, 59.5 Gy to PTV59 including postoperative bed and dissected neck, and 56Gy to PTV56 elective volumes at risk for subclinical disease including contralateral undissected neck.

Weekly carboplatin(AUC 1) and paclitaxel(30 mg/m2) were administered in patients receiving chemoradiation. Patients were seen weekly for toxicity evaluations and management.

Response and Follow Up

Three months following completion of definitive therapy, patients underwent PET/CT and physical examination. If there was no concern for persistent disease, patients underwent surveillance follow-up every three months for three years after completion of definitive treatment with yearly chest imaging(chest CT or X-ray at the discretion of the treating physician).

Quality of Life Assessment

Videofluoroscopic evaluation of swallowing was obtained prior to neck dissection and one year after the completion of therapy. Quality of life instruments(HN-QOL and neck dissection impairment index- NDII) were administered prior to neck dissection, prior to radiation therapy, then every three months for three years after completion of definite treatment.

Statistical Considerations

The primary objective of this single arm phase II clinical trial was to assess whether pathologic results from upfront neck dissection can be used to select subsequent treatment to minimize treatment modalities and thereby improve functional outcomes. We hypothesized that the proposed paradigm could improve quality of life compared to a historical control group. The historical cohort consisted of patients with OPSCC treated on a phase II clinical trial with weekly carboplatin and paclitaxel with concurrent IMRT that spared the constrictors, larynx and major salivary glands[5, 18]There was no difference is age, sex, smoking history, and T classification. There was a difference in N classification if stratified by AJCC 7th edition, but not if stratified by AJCC 8th edition. For the functional outcome in our historical control data, the largest variance in HNQOL was the eating domain score at one year which worsened by a mean of −13, indicating a significant decline. Therefore, we set the primary endpoint as the one- year eating domain quality of life.

We planned to perform propensity adjusted(weighted) linear regression analysis to estimate the causal effect of our proposed treatment strategy on the mean change score at one year compared to our historical control data. A power analysis, assuming a type I error rate of 5%, was conducted based on two methods of analysis: (a) a two-sample t-test of the change scores, and (b) an analysis of covariance(ANCOVA) 51 of the change(1 year post- pretreatment) after covariate adjustment for propensity score strata. Matching the historical cohort to our inclusion criteria (p16+, non T4, non N3), we found that the difference in mean EATING score change from −13 to −3 would have 90% power with 90 evaluable patients[18]. To achieve 80% power under this scenario 48 evaluable patients were required. We developed stopping rules for mortality or neck dysfunction that were monitored but did not trigger early stopping.

A planned interim analysis was performed after enrollment of 30 patients and initial results were compared to our matched historical dataset per protocol after the last patient had 12 months of follow up after completion of therapy. The steering committee reviewed the interim results and based on our positive significant findings in HNQOL at the primary endpoint, and emerging data regarding efficacy of de-escalation of HPV+ oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma, it was decided to stop early. We performed a propensity score weighted analysis (for cohort membership) to minimize potential bias and multivariable models were performed with covariates for T classification, N classification and smoking (yes/no). A two-sided p-value less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Data Availability

The data generated in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author to maintain patient privacy per institutional policy.

Results

Patient Characteristics

Thirty-four patients were enrolled between October 2016 and April 2019. One patient had a ruptured lymph node during their neck dissection. The case was discussed in a multidisciplinary tumor board, and it was decided to take the patient off-study and treat with definitive chemoradiation(Figure 1). The remaining thirty-three patients were included in analysis for treatment related toxicities, quality of life, and disease outcomes. The baseline demographics of these patients are shown in Table 1. The Representativeness of Study Participants are shown in Supplementary Table 1.

Table 1:

Patient and Tumor Characteristics

| n or median (range), n=33 | |

|---|---|

| Age, years | 61 (40–76) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 27 (82%) |

| Female | 6 (18%) |

| Race | |

| White | 32 |

| Black | 1 |

| ECOG performance status | |

| 0 | 31 |

| 1 | 2 |

| Smoking History | |

| No | 21 (64%) |

| Yes | 12 (36%) |

| Pack Years | 10 (0.75 –24) |

| Disease Location | |

| Tonsil | 25 (76%) |

| Tongue base | 8 (24%) |

| Initial T Stage* | |

| T1 | 21 (64%) |

| T2 | 10 (30%) |

| T3 | 2 (6%) |

| Initial N Stage* | |

| N0 | 7 (21%) |

| N1 | 16 (48%) |

| N2a | 2 (6%) |

| N2b | 8 (24%) |

| Number of Nodes | 1 (0–5) |

| Extracapsular Spread | |

| Yes | 10 |

| No | 23 |

| Perineural Invasion | |

| Yes | 1 |

| No | 32 |

| Perivascular Invasion | |

| Yes | 0 |

| No | 33 |

per AJCC 7th Edition

Neck Dissection and Treatment Stratification

All patients underwent selective neck dissection. Thirty-two patients underwent levels II-IV and one patient underwent levels I-IV. There were no reported complications from neck dissection(including cranial nerve injury or hematoma). Based on the results of the neck dissection 42%(14/33) of patient were assigned to TORS, 30%(10/33) to radiation alone, and 27%(9/33) to chemoradiation. TORS was performed at an average of 15.8 days from neck dissection(range 9–27).Recognizing that increased numbers of treatment modalities to the primary site results in greater acute and late toxicities, the goal of this paradigm was to decrease the number of treatments to the primary site[4]. To calculate the number of patients de-escalated in this study, we considered a primary surgical paradigm of treatment: surgery (primary resection and neck dissection) followed by directed adjuvant therapy (radiation with or without chemotherapy). If all patients underwent a primary surgical approach with upfront TORS and neck dissection, 57%(19/33) of patients in this study that underwent adjuvant therapy would have not needed the TORS resection (10 received radiation alone and 9 received chemoradiation). Detailed data regarding the changes in clinical stage and pathologic stage before and after neck dissection are characterized in Supplemental Table 2.

Two patients underwent staging neck dissection and failed to complete protocol dictated treatment; both were taken off trial. One was assigned to chemoradiation; however, the patient refused chemotherapy and was treated with radiation alone. The second patient was stratified to TORS, but resection was aborted due to poor transoral access. The patient was treated with radiation alone.

Treatment Related Toxicities

Treatment related toxicities were measured within one month, at 180 days and > 180 days after staging neck dissection and are shown stratified by treatment arm(TORS, radiation, or chemoradiation) in Table 2. No grade 4 or 5 toxicities were observed. Acutely(within 30 days of neck dissection), two patients treated with TORS experienced oropharyngeal bleeding which required a single return to the operating room. One hundred and eighty days was chosen to reflect the acute effects of radiation(and potentially chemotherapy). The overall rates of grade 2 or 3 adverse events was slightly higher in patients treated with chemoradiation versus radiation alone with increased rates of dysgeusia(86% vs 50%), dysphagia(43% vs 10%), and pain(86% vs 40%). Given the limited sample size, these differences were not statistically significant. Long-term grade 2 or 3 treatment related adverse events(>180 days from staging neck dissection) were rare.

Table 2:

Rates of Treatment Related Toxicities of Interest

| Within 30 Days of Neck Dissection | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arm | TORS (n=13) | Radiation Alone (n=10) | Chemoradiation (n=7) | Total (n=30) |

| Dry Mouth | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Dysphagia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Fatigue | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Mucositis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Oral Hemorrhage | 2 (15%) | 0 | 0 | 2 (6%) |

| Pain | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Weight loss | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Within 180 Days of Neck Dissection** | ||||

| Arm | TORS (n=13) | Radiation Alone (n=10) | Chemoradiation (n=7) | Total (n=30) |

| Dry Mouth | 0 | 3 (30%) | 3 (43%) | 6 (20%) |

| Dysgeusia | 0 | 5 (50%) | 6 (86%) | 11 (37%) |

| Dysphagia | 0 | 1 (10%) | 3 (43%) | 4 (13%) |

| Fatigue | 0 | 2 (20%) | 2 (29%) | 4 (13%) |

| Mucositis | 0 | 6 (60%) | 6 (86%) | 12 (40%) |

| Oral Hemorrhage | 2 (15%) | 0 | 0 | 2 (7%) |

| Pain | 0 | 4 (40%) | 6 (86%) | 10 (33%) |

| Weight loss | 0 | 1 (10%) | 0 | 1 (3%) |

| Greater than 180 days from Neck Dissection | ||||

| Arm | TORS (n=13) | Radiation Alone (n=10) | Chemoradiation (n=7) | Total (n=30) |

| Dry Mouth | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Dysgeusia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Dysphagia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Fatigue | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Mucositis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hypothyroidism | 0 | 1 (10%) | 0 | 1 (3%) |

| Pain | 0 | 1 (10%) | 0 | 1 (3%) |

| Weight loss | 0 | 1 (10%) | 0 | 1 (3%) |

Includes Grade 2 and 3 treatment related toxicities. There were no Grade 4 toxicities observed

Is inclusive of those toxicities seen within 30 days of neck dissection

Quality of Life

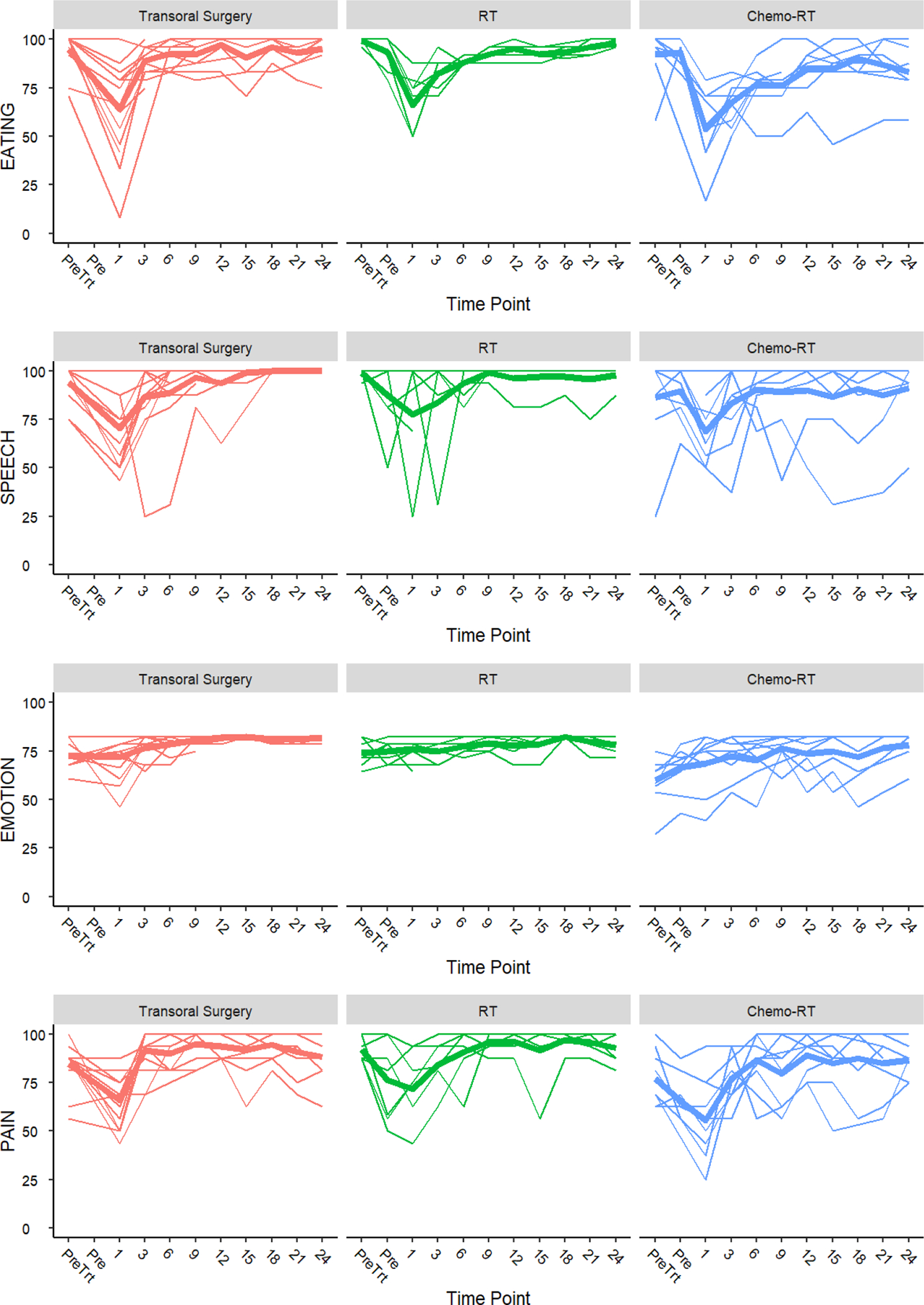

Figure 2 show the HNQOL domains stratified by treatment arm. Overall, there was an improvement in the entire cohort in the pain and emotions domains at one year following completion of therapy. There was a slight decrease in the eating and speech subscore. The primary endpoint of the de-escalation study was to reduce the negative impact of treatment on eating quality of life at one-year relative to standard treatment. We saw a significant improvement in the eating domain in the HNQOL compared to matched historical controls (p=0.034). We saw lesser improvements in the speech, pain and emotional quality of life scores that were not statistically significant(p=0.49, 0.15, 0.30, respectively). Of note, the study was powered to the eating domain, resulting in a positive study. In addition, we saw no changes in the UWQOL at 1 year and 2 years, including the chewing and swallowing domains(data not shown).

Figure 2:

Longitudinal Head and Neck Quality of Life Outcomes Stratified by Functional Domain. Pre-treatment (Pre Trt), Pre-radiation (Pre).

Because all patients underwent selective neck dissection, we hoped to ensure retention of normal neck function. Table 3 show the results of the NDII stratified by treatment arm. We have previously reported on the impairment of neck function in patients undergoing chemoradiation +/− surgery nested in the same historical cohort used for our power calculations[19]. The mean NDII score for our historical cohort was 87.4(SD 22.1, range 5–100)[19]. The addition of neck dissection in this study results in a 1- and 2-year NDII score of 96.2 and 96.7 respectively (perfect score=100). Compared to the historic cohort, there was a significant improvement in NDII(p=0.019).

Table 3:

Neck Dissection Impairment Index

| Timepoint | Mean | Std Dev | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PreTreatment | 96.7 | 4.6 | 80 | 100 |

| Pre RT or CRT | 77.6 | 15.7 | 48 | 100 |

| (months post treatment) | ||||

| 1 | 86 | 12.4 | 50 | 100 |

| 3 | 92.4 | 8.7 | 64 | 100 |

| 6 | 96.5 | 4.6 | 86 | 100 |

| 9 | 96 | 7.5 | 72 | 100 |

| 12 | 96.2 | 5 | 84 | 100 |

| 15 | 96.1 | 5.9 | 82 | 100 |

| 18 | 97.1 | 4.8 | 80 | 100 |

| 21 | 96.5 | 4.1 | 84 | 100 |

| 24 | 96.7 | 5.1 | 78 | 100 |

| 27 | 96.6 | 7.8 | 64 | 100 |

| 30 | 97.4 | 4.8 | 82 | 100 |

| 33 | 98.5 | 2.6 | 92 | 100 |

| 36 | 98.8 | 1.6 | 96 | 100 |

Swallowing Function

Swallowing function was evaluated with objective measures including a pretreatment and 1-year post-treatment videofluoroscopic swallow study. No patients developed feeding tube dependence. The specific swallowing functionality is shown in Supplemental Table 3. We observed improvements in pharyngeal weakness after treatment in 3 patients. Aspiration was seen in 0 patients before treatment and in 1 patient after treatment, although this was trace. Penetration was seen in 9 patients before treatment and 10 patients after treatment.

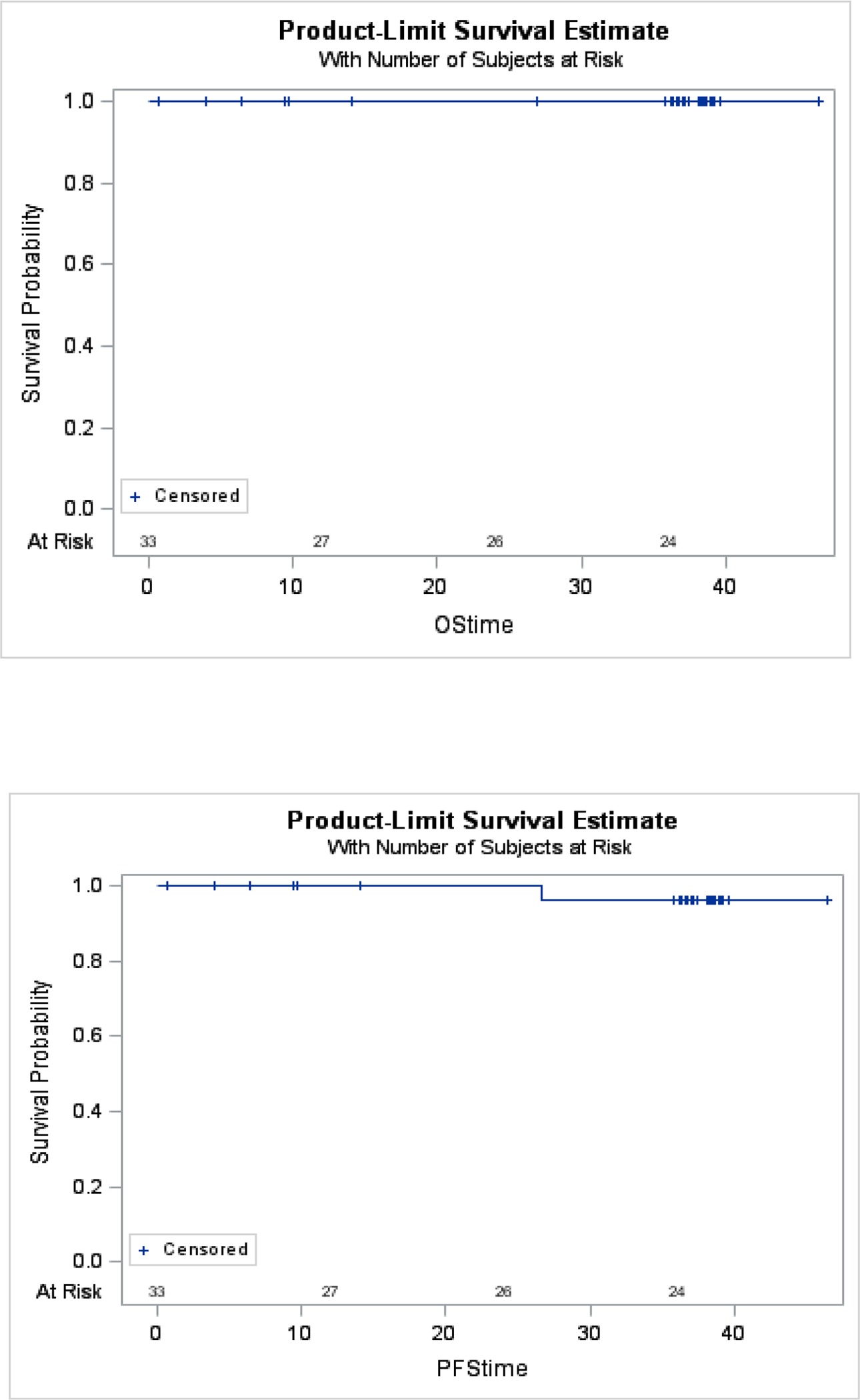

Survival

The median follow-up duration among all enrolled study participants was 37 months. All patients assigned to a treatment modality post neck dissection(TORS, RT, CRT) had follow-up greater than 36 months. The 3-year overall survival of 100% and 3-year estimated progression free survival of 96%(95% CI: 76, 99%)(Figure 3). One patient experienced a locoregional recurrence at 27 months. The patient was initially treated with TORS and the locoregional recurrence was treated with chemoradiation. The patient remains disease free at the time of analysis.

Figure 3:

Kaplan Meier estimates of Overall Survival and Progression Free Survival

Discussion

This study examines a novel treatment paradigm incorporating up-front neck dissection for subsequent treatment selection in patients with low-risk HPV-related OPSCC. Our data demonstrate that such a treatment paradigm may offer improved quality of life by avoiding trimodality therapy to the primary site when compared to historical treatment controls.

The major driver of adjuvant therapy after surgical resection in HPV-related OPSCC is the extent of neck disease. More than 80% of patients present with neck disease on presentation[20], and the most common indication for adjuvant radiation therapy is the degree of nodal involvement as well as presence of ECS. Indications for adjuvant radiation to the primary site, such as positive margins or perineural invasion are uncommon[8]. Patients destined for trimodality therapy to the primary site may be better suited to avoid transoral surgery up front to minimize treatment related toxicities. There is an accumulating body of literature supporting worse quality of life with trimodality therapy compared to surgery plus adjuvant radiation or definitive chemoradiation[21, 22]. However, identifying patients that can avoid trimodality therapy based on the extent of neck disease is difficult. PET and CT imaging have a sensitivity and specificity of 37.6–77% and 60–97% respectively[12], but the overall accuracy is closer to 60%[12, 16, 23]. An upfront neck dissection can add both diagnostic information in patients who have more extensive disease and therapeutic value in patients who do not require any adjuvant treatment. The availability of this pivotal information prior to primary tumor resection allows appropriate selection of patients for treatment with either surgery, radiation or chemoradiation.

The results of ECOG 3311 have informed us that surgery is feasible in patients with HPV-related OPSCC. Importantly in this study, there were 11% of patients who underwent surgery alone, 58% of patients who had surgery and radiation(dual modality) and 31% of patients with surgery followed by chemoradiation(trimodality). Our paradigm allowed single modality treatment to the primary site(surgery or radiation) in 73% of patients, and dual modality therapy in 27% of patients. By staging the neck dissection, this allowed the 27% of patients who would have typically gotten surgery up front on the primary site in 3311 to avoid this modality altogether. This not only avoids the risk of surgical complications, but also improves the quality of life in this patient population, without changes to survival.

Currently there are limited randomized controlled trials comparing radiation-based treatment to surgically-based treatment in HPV+ OPSCC. The first ORATOR trial randomized patients to radiotherapy +− chemotherapy or surgery +− adjuvant therapy based on pathology. This study showed slightly superior 1-year swallowing function in the radiation cohort but was not considered clinically meaningful[9]. Based on treatment stratification, 23%(19 patients) underwent single modality to the primary site, 48%(39 patients) underwent dual modality to the primary site, and 29%(23 patients) underwent triple modality therapy, demonstrating a significant number of patients assigned to trimodality therapy ORATOR2 had a similar randomized design that sought to expand and further validate the results of ORATOR, but was closed early given the toxicity in the surgical arm. [24] All three deaths occurred in the surgical arm, with two of the three deaths directly related to transoral resection. This further strengthens the argument of carefully selecting patients to undergo primary site resection based on the avoidance of other therapies.

ECOG 3311 randomized patients to receive 50 vs 60 gray of radiation in an adjuvant fashion and showed no differences in reported recurrence or quality of life outcomes. Despite a large variation of the radiation dose to the primary site and nodal basins between institutions and within the treatment arms that could affect treatment efficacy/quality of life, these data do suggest the efficacy of de-escalated adjuvant therapy, but important to note this is phase 2 and not phase 3 data and will require additional studies to validate. There are multiple additional single institution trials that further suggest decreasing adjuvant dosing to as low as 30–36 gray may be feasible for maintaining survival in very select patient cohorts[10, 11, 25, 26].

Radiation based de-escalation strategies have shown success in HPV+ OPSCC. Chera et al showed that patients receiving weekly chemotherapy with 60 Gy with limited smoking history had similar survival that historical controls. [27] There was also favorable long-term swallowing function (2-year). Similarly, Chen et al used induction chemotherapy to select patients for de-escalation (complete or partial responders 54 Gy versus 60Gy). [28] Approximately half of the cohort was de-escalated to 54 Gy, and they showed patients could be safely de-escalated with a lower side effect profile based on response to induction. Future trials could combine the decrease in dose to the primary site, coupled with the selection of patients who can avoid radiation all together based on neck dissection to personalize treatment in HPV+ OPSCC.

De-escalated therapy based on the sub-stratification of ECS into micro and macro ECS is also of interest. In retrospective analyses MicroECS was thought to have less of a survival impact than macroECS. In our cohort, ten patients were found to have ECS, seven of which were micro-ECS(<1mm) with the remaining three being macro-ECS(>1mm). This suggests that fewer patients may require adjuvant chemotherapy with radiation as we further define the prognostic value of the substratifications of ECS[29, 30]. However, even in recently published de-esclation cohorts, there is a significant difference in survival of patients with ECS when treated with de-escalated adjuvant RT doses[10], highlighting the importance of precise patient selection.

The concept of neck dissection up front has the potential to be considered as an addition of treatment in some patients and could affect shoulder function. Our group has previously published on the impact of shoulder function on patients undergoing chemoradiation for HPV+OPSCC utilizing carboplatin and paclitaxel.[19] In this cohort the average NDII was 87.4/100, and is significantly worse that patients in our current study (p=0.019). Two factors that worsen shoulder function in patients undergoing primary chemoradiation for HPV+ OPSCC is the addition of salvage neck dissection to treatment and large radiation treatment volumes. This is likely due to 1) salvage neck dissection is more morbid than pretreatment neck dissection and 2) the volume of radiation delivered in post-surgical patients is lower and has less morbidity. Further research on the type and extent of neck dissection may elucidate further differences.

An important note is the lack of exact matching from our historical cohort to this study. While we were able to propensity match patients to create our power calculations, the differences in treatment to the primary site and changes in the AJCC staging system, which effect the inclusion criteria, can limit the interpretation of these results. In addition, our institutional preference is to use weekly carboplatin and paclitaxel as radiation sensitizers in the treatment of HPV related OPSCC. While our published data has shown similar efficacy with less side effects that high dose cisplatin[5, 18], this can introduce a bias when applying this paradigm more broadly.

This study required careful interdisciplinary and multidisciplinary planning to prevent treatment delays. Typically, patients were booked for neck dissection and robotic resection at the same time as to reserve the operating room. Pathologic evaluation was expedited in these cases to ensure appropriate arm selection. The generalizability of this paradigm would require a high level of management if this were brough forward as a national trial.

In this study, 14/33 patients required two anesthetics when brought back to the operating room for primary resection, which may increase the perioperative risk. Currently, many institutions already perform neck dissection and robotic surgery separately because of operating room access to the robot, although this has institutional variance. While we did not have any perioperative complications related to this second anesthetic, careful counseling of patients is important to explain this increased risk when utilizing this paradigm.

Another important limitation in this study is the selection of our historical control group. While the historical cohort had excellent disease control and quality of life outcomes [5], a modern control group may have allowed a better comparison of IMRT techniques that are more conformal with lower elective doses given over time. Thus the improved quality of life seen in this study may be similar to a modern radiation cohort. As such, future studies examining a neck dissection-based treatment paradigm should be powered using modern IMRT techniques to expand and validate these results.

In conclusion, treatment with upfront neck dissection in patients with locally advanced HPV+ OPSCC may improve quality of life when compared to our historical cohort, without compromising survival outcomes. Further research using this treatment paradigm is necessary to understand the full clinical significance of this strategy.

Supplementary Material

Translational relevance:

Current de-escalation trials in patients with HPV+OPSCC are underway to mitigate acute and long-term toxicities of treatment without compromising survival. We designed a phase II trial for patients with HPV+OPSCC to evaluate the feasibility of an upfront neck dissection to individualize treatment selection to improve quality of life without compromising survival. Our work demonstrates that a neck dissection up front may improve treatment selection, with 76% of patients receiving single modality (radiation or surgery alone) and 24% of patients receiving dual modality therapy. With the primary endpoint of this study met, we showed improvement in the 1 year post treatment quality of life scores when compared to historical controls. In addition, we had a 100% three year overall survival and 96% three year disease specific survival, demonstrating the early safety of this treatment paradigm.

Funding Statement:

This work was supported by NIH/NIDCD T32 DC005356, as well as University of Michigan Cancer Center Core Grant NIH/NCI P3O CA046592

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest

Previous Presentation Statement:

The Manuscript was presented at the American Head and Neck Society International Meeting in Montreal, Canada

References:

- 1.Chaturvedi AK, et al. , Human papillomavirus and rising oropharyngeal cancer incidence in the United States. J Clin Oncol, 2011. 29(32): p. 4294–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Overcoming Barriers to Low HPV Vaccine Uptake in the United States: Recommendations from the National Vaccine Advisory Committee: Approved by the National Vaccine Advisory Committee on June 9, 2015. Public Health Rep, 2016. 131(1): p. 17–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ang KK, et al. , Human papillomavirus and survival of patients with oropharyngeal cancer. N Engl J Med, 2010. 363(1): p. 24–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goyal N, et al. , Head and neck cancer survivorship consensus statement from the American Head and Neck Society. Laryngoscope Investig Otolaryngol, 2022. 7(1): p. 70–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feng FY, et al. , Intensity-modulated chemoradiotherapy aiming to reduce dysphagia in patients with oropharyngeal cancer: clinical and functional results. J Clin Oncol, 2010. 28(16): p. 2732–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eisbruch A, et al. , Chemo-IMRT of oropharyngeal cancer aiming to reduce dysphagia: swallowing organs late complication probabilities and dosimetric correlates. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys, 2011. 81(3): p. e93–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vainshtein JM, et al. , Patient-reported voice and speech outcomes after whole-neck intensity modulated radiation therapy and chemotherapy for oropharyngeal cancer: prospective longitudinal study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys, 2014. 89(5): p. 973–980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferris RL, et al. , Phase II Randomized Trial of Transoral Surgery and Low-Dose Intensity Modulated Radiation Therapy in Resectable p16+ Locally Advanced Oropharynx Cancer: An ECOG-ACRIN Cancer Research Group Trial (E3311). J Clin Oncol, 2022. 40(2): p. 138–149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nichols AC, et al. , Radiotherapy versus transoral robotic surgery and neck dissection for oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (ORATOR): an open-label, phase 2, randomised trial. Lancet Oncol, 2019. 20(10): p. 1349–1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ma DJ, et al. , Phase II Evaluation of Aggressive Dose De-Escalation for Adjuvant Chemoradiotherapy in Human Papillomavirus-Associated Oropharynx Squamous Cell Carcinoma. J Clin Oncol, 2019. 37(22): p. 1909–1918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miles BA, et al. , De-Escalated Adjuvant Therapy After Transoral Robotic Surgery for Human Papillomavirus-Related Oropharyngeal Carcinoma: The Sinai Robotic Surgery (SIRS) Trial. Oncologist, 2021. 26(6): p. 504–513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morey T, et al. , Correlation between radiologic and pathologic extranodal extension in HPV-associated oropharyngeal cancer: Systematic review. Head Neck, 2022. 44(12): p. 2875–2885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nemmour A, et al. , Prediction of extranodal extension in oropharyngeal cancer patients and carcinoma of unknown primary: value of metabolic tumor imaging with hybrid PET compared with MRI and CT. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol, 2023. 280(4): p. 1973–1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heft Neal ME, et al. , Predictors and Prevalence of Nodal Disease in Salvage Oropharyngectomy. Ann Surg Oncol, 2020. 27(2): p. 451–457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Samant S and Robbins KT, Evolution of neck dissection for improved functional outcome. World J Surg, 2003. 27(7): p. 805–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Snyder V, et al. , PET/CT Poorly Predicts AJCC 8th Edition Pathologic Staging in HPV-Related Oropharyngeal Cancer. Laryngoscope, 2021. 131(7): p. 1535–1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spector ME, et al. , Matted nodes as a predictor of distant metastasis in advanced-stage III/IV oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Head Neck, 2016. 38(2): p. 184–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dobrosotskaya IY, et al. , Weekly chemotherapy with radiation versus high-dose cisplatin with radiation as organ preservation for patients with HPV-positive and HPV-negative locally advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the oropharynx. Head Neck, 2014. 36(5): p. 617–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burgin SJM, et al. , Long-term neck and shoulder function among survivors of oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma treated with chemoradiation as assessed with the neck dissection impairment index. Head Neck, 2021. 43(5): p. 1621–1628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sood AJ, et al. , The association between T-stage and clinical nodal metastasis In HPV-positive oropharyngeal cancer. Am J Otolaryngol, 2014. 35(4): p. 463–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gross JH, et al. , Predictors of swallow function after transoral surgery for locally advanced oropharyngeal cancer. Laryngoscope, 2020. 130(1): p. 94–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Quon H, O’Malley BW Jr., and Weinstein GS, Transoral robotic surgery and a paradigm shift in the management of oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. J Robot Surg, 2010. 4(2): p. 79–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Park SI, et al. , The diagnostic performance of CT and MRI for detecting extranodal extension in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: a systematic review and diagnostic meta-analysis. Eur Radiol, 2021. 31(4): p. 2048–2061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Palma DA, et al. , Assessment of Toxic Effects and Survival in Treatment Deescalation With Radiotherapy vs Transoral Surgery for HPV-Associated Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma: The ORATOR2 Phase 2 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol, 2022. 8(6): p. 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moore EJ, et al. , Human papillomavirus oropharynx carcinoma: Aggressive de-escalation of adjuvant therapy. Head Neck, 2021. 43(1): p. 229–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Swisher-McClure S, et al. , A Phase 2 Trial of Alternative Volumes of Oropharyngeal Irradiation for De-intensification (AVOID): Omission of the Resected Primary Tumor Bed After Transoral Robotic Surgery for Human Papilloma Virus-Related Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Oropharynx. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys, 2020. 106(4): p. 725–732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chera BS, et al. , Phase II Trial of De-Intensified Chemoradiotherapy for Human Papillomavirus-Associated Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. J Clin Oncol, 2019. 37(29): p. 2661–2669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen AM, et al. , Reduced-dose radiotherapy for human papillomavirus-associated squamous-cell carcinoma of the oropharynx: a single-arm, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol, 2017. 18(6): p. 803–811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bauer E, et al. , Extranodal extension is a strong prognosticator in HPV-positive oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Laryngoscope, 2020. 130(4): p. 939–945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beltz A, et al. , Significance of Extranodal Extension in Surgically Treated HPV-Positive Oropharyngeal Carcinomas. Front Oncol, 2020. 10: p. 1394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data generated in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author to maintain patient privacy per institutional policy.