Abstract

The EICP22 protein (EICP22P) of Equine herpesvirus 1 (EHV-1) is an early protein that functions synergistically with other EHV-1 regulatory proteins to transactivate the expression of early and late viral genes. We have previously identified EICP22P as an accessory regulatory protein that has the ability to enhance the transactivating properties and the sequence-specific DNA-binding activity of the EHV-1 immediate-early protein (IEP). In the present study, we identify EICP22P as a self-associating protein able to form dimers and higher-order complexes during infection. Studies with the yeast two-hybrid system also indicate that physical interactions occur between EICP22P and IEP and that EICP22P self-aggregates. Results from in vitro and in vivo coimmunoprecipitation experiments and glutathione S-transferase (GST) pull-down studies confirmed a direct protein-protein interaction between EICP22P and IEP as well as self-interactions of EICP22P. Analyses of infected cells by laser-scanning confocal microscopy with antibodies specific for IEP and EICP22P revealed that these viral regulatory proteins colocalize in the nucleus at early times postinfection and form aggregates of dense nuclear structures within the nucleoplasm. Mutational analyses with a battery of EICP22P deletion mutants in both yeast two-hybrid and GST pull-down experiments implicated amino acids between positions 124 and 143 as the critical domain mediating the EICP22P self-interactions. Additional in vitro protein-binding assays with a library of GST-EICP22P deletion mutants identified amino acids mapping within region 2 (amino acids [aa] 65 to 196) and region 3 (aa 197 to 268) of EICP22P as residues that mediate its interaction with IEP.

Equine herpesvirus 1 (EHV-1), a member of the subfamily Alphaherpesvirinae, is a major pathogen of equines (1, 14, 42). Infection with EHV-1 is associated with clinical complications ranging from respiratory infection and neurological disorders to spontaneous abortions in pregnant mares (1, 14, 42). EHV-1 genes are regulated at the transcriptional level, and the gene products are synthesized in a coordinate temporal order as immediate-early, early, and late, analogous to those of other alphaherpesviruses (11, 22, 23). The transcription program of the EHV-1 genome has been defined as a single immediate-early (IE) gene, 49 early (E) genes, and 26 late (L; γ1 and γ2) genes (11, 22, 23, 27, 57, 64). The sole IE gene is essential (19) and is transcribed as a 6.0-kb mRNA that encodes several IE protein (IEP) species that arise by posttranslational modification and migrate on sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) gels between 150 and 200 kDa (9, 10, 25, 26).

Functionally, IEP has been characterized as a sequence-specific transcriptional activator (55). Previous studies revealed that IEP contains a site-specific DNA-binding domain (amino acids [aa] 422 to 597), a nuclear localization signal (aa 963 to 970), and a functional transactivation domain that is enriched in charged amino acids and maps to the amino terminus at residues 3 to 89 (34, 56, 58). The EICP27, EICP0, and EICP22 proteins (EICP27P, EICP0P, and EICP22P) interact synergistically with IEP in transient-transactivation assays with various EHV-1 promoters (3, 27, 32, 55). Additionally, the IE promoter is negatively autoregulated by IEP and other EHV-1 regulatory proteins to control expression of the IE protein. The IR2 protein is an example of a negative IE gene regulator, since this early regulatory protein lacks the IEP transactivation domain, but harbors the DNA-binding domain that can down-regulate IE gene expression (26, 34).

The major focus of this investigation is EICP22P, which is encoded by the EICP22 (IR4) gene, the fourth gene within each inverted repeat of the short genomic region of EHV-1. ICP22P homologs have been identified in other herpesviruses including herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) (39, 45), EHV-4 (15), pseudorabies virus (63), bovine herpesvirus type 1 (52), varicella-zoster virus (16) VZV Marek's disease virus (51), herpesvirus of turkeys (62), and simian varicella virus (24). Although the functions of these proteins are poorly understood, results from various laboratories investigating HSV-1 ICP22P have outlined some characteristics of this immediate early protein (5, 8, 36, 45–47, 49, 53). Interestingly, ICP22P has both positive and negative transcriptional effects on various HSV-1 promoters, which are mediated by its interactions with other HSV-1 regulatory proteins (48, 49). Other recent studies implicated ICP22P in the phosphorylation of the carboxyl-terminal domain of the cellular RNA polymerase II (49), a function that appears to be related to the role of ICP22P in viral gene transcription (36).

The EHV-1 EICP22 gene is transcribed as 3′ coterminal early 1.4-kb and late 1.8-kb transcripts that potentially can express proteins of 293 (major) and 469 aa, respectively (29, 30). EICP22P migrates as several species between 42 and 47 kDa on SDS-PAGE gels, is heavily phosphorylated, and localizes to the nucleus to form punctate bodies as revealed by immunofluorescence studies (28; D. E. Bowles and D. J. O'Callaghan, unpublished observations). Western blot analysis of purified virion preparations indicated that EICP22P is present in the tegument-nucleocapsid fraction of the virion (28). The role of EICP22P in gene regulation was addressed in transient-transactivation assays, which indicated that EICP22P (i) by itself can only minimally transactivate EHV-1 promoters; (ii) acts synergistically with EICP27Protein up-regulate the IE promoter; (iii) does not interfere with IE autoregulation; (iv) acts synergistically with EICP0P to enhance expression from both early and late promoters; and (v) acts synergistically with IEP to enhance expression of HSV-1 promoters (28, 29; Bowles and O'Callaghan, unpublished). Gel shift studies with radiolabeled DNA probes did not reveal any in vitro DNA-binding activity for EICP22P (33, 34). In studies investigating the DNA-binding characteristics of IEP, EICP22P was shown not only to enhance the ability of IEP to bind to all early and late promoters tested but also to increase the rate at which IEP binds to its target sequence and to enhance the transcription of EHV-1 promoter-reporter constructs by the IE mutants (33). Interestingly, results of gel shift assays with mutant forms of IEP altered in the conserved WLQN DNA-binding region indicated that purified glutathione S-transferase (GST)-EICP22P fusions were able to restore the DNA binding of some mutants (33; S. K. Kim and D. J. O'Callaghan, unpublished observations).

In the present study, further characterization of EICP22P has demonstrated that physical interactions occur between EICP22P and IEP. These investigations also identified EICP22P as a self-associating protein that forms dimers and higher-order complexes during infection. By using various in vivo and in vitro protein-binding assays, we demonstrate that (i) EICP22P physically binds to IEP and to itself, forming stable complexes; (ii) amino acids mapping within region 2 (aa 65 to 196) and region 3 (aa 197 to 268) of EICP22P mediate its interaction with IEProtein, and (iii) aa 124 to 143 of EICP22P are required for the self-interaction of this protein.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacteria, viruses, and cell culture.

Mouse fibroblast L-M cells were propagated as described previously (3, 11, 55). EHV-1 infections were performed in L-M cells grown as monolayers in Eagle's minimum essential medium supplemented with penicillin (100 U/ml), streptomycin (100 μg/ml), nonessential amino acids, and 2% fetal bovine serum. The monolayers were infected with the EHV-1 KyA strain at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10, and cell lysates were harvested at 12 h postinfection as described previously (3, 30). Methods for the expression of GST fusion plasmids in the BL21(DE3)pLysE strain of Escherichia coli and for purification of the fusion proteins were described previously (34).

Plasmids.

The pcDR4, pRDR4(Δ) deletion mutants, pGST-EICP22, pGST-EICP22(Δ)-deletion mutants, pGem44z(IR2), pGemIE, pSVIE, and AMPGST-gD constructs were previously generated and are described elsewhere (27, 29, 34, 55). The yeast vectors pACTII (Clontech), which expresses the GAL4 activation domain (aa 768 to 881), and pAS1-CYH2 (a generous gift of S. J. Elledge), which possesses the GAL4 DNA-binding domain (aa 1 to 147), were the parent vectors.

(i) Construction of the pACTIR4 (EICP22-activation domain fusion) two-hybrid vector.

PCR primers 22UN (5′AAAGATAGATCTGAATTCGCCCAGCCATGGCCCACG3′) and 22DN (5′GGGGGATCCGTCGACGGGCATGCGTACACCTAT3′) were used to generate an upstream NcoI site and a downstream SalI site, respectively, that flank the EICP22 gene of the previously described pcDR4 mammalian expression vector (28). The PCR product was digested with NcoI and SalI to release a 390-bp NcoI fragment and a 510-bp NcoI-SalI fragment. The 510-bp NcoI-SalI fragment was first ligated into NcoI-XhoI-digested pACTII to generate the pACTIR4ΔNcoI intermediate. The 390-bp NcoI fragment was then ligated into NcoI-digested pACTIR4ΔNcoI to generate an in-frame fusion of full-length EICP22 with the activation domain of GAL4.

(ii) Construction of the pASCYHIR4 (EICP22–DNA-binding fusion) two-hybrid vector.

The PCR product described above also incorporated a further upstream 5′ EcoRI site that would cut in frame with the NcoI site. A second digestion of the PCR product was performed with EcoRI-SalI, and a subsequent ligation was performed into EcoRI-SalI-digested pAS1-CYH2 to generate the in-frame, full-length EICP22-GAL4 DNA-binding fusion two-hybrid vector.

(iii) Construction of the EICP22P deletion mutant two-hybrid vectors.

The previously described (33) EICP22P deletion mutant constructs [pcDR4(Δ)] were restriction digested with either EcoRI-PvuII (see Fig. 6, M1 to M5) or NarI-SgrAI (see Fig. 6, M6 to M8). The released fragments were ligated into correspondingly digested pACTIR4 in which the selected enzymes would cut only within the EICP22 open reading frame (ORF). The vectors were sequenced across the restriction sites and cotransformed along with pASCYHIR4 into the SFY526 (Clontech) or PJ-694A (gift of Kelly Tatchell) yeast strain.

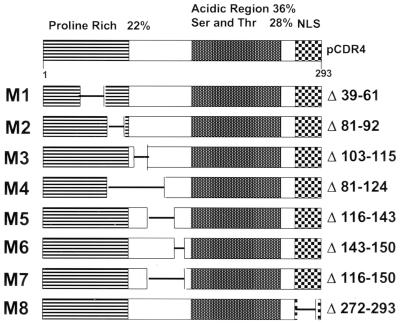

FIG. 6.

Mutant forms of EICP22P. The various deletion mutant constructs of the EICP22 gene were subcloned into the pACTII GAL4 activation plasmids and designated pACT-M1 to pACT-M8 (Table 2). In addition, these deletion mutants of the EICP22 gene were cloned into pGEM expression plasmids for use in in vitro transcription-translation reactions. The predicted forms of EICP22P showing the various deletions are presented. The top diagram shows the four regions of EICP22P.

Generation of the IEP two-hybrid vectors.

The simian virus 40 promoter-driven, full-length IE mammalian expression vector, pSVIE, was digested with NcoI-BamHI to release the 5′ 1,270-bp portion of the IE ORF, which was ligated into NcoI-BamHI-digested pACTII to generate the pACTIEΔBE intermediate. The pSVIE plasmid was then cut with BamHI-EcoRI to release the 3′ 3,480-bp portion of the IE ORF, which was ligated into the NcoI-EcoRI-digested pACTIEΔBE. The resultant vector, pACTIEP, is a fusion between the full-length IE sequence and the activation domain of GAL4. For the construction of the IE-GAL4 DNA-binding fusion, pSVIE was cut with BamHI-NcoI to remove the 5′ 1.3-kb fragment of IE, which was cloned into NcoI-BamHI-digested pAS1-CYH2 to create the pASCYHIEΔBam intermediate. Another IE expression plasmid, pGEMIE, was cut with BamHI to release the 3.5-kb BamHI fragment, which was ligated into BamHI-digested pASCYHIEΔBam. The resultant construct, pASCYHIE, represents the fusion between full-length IE and the DNA-binding domain of GAL4. The plasmids pACTGac-1 and pAS1-CYHPP-1 (both supplied by K. Tatchell), in which Gac1 is a regulatory subunit of the yeast phosphatase type 1 known to physically associate strongly with the PP-1 protein (18), served as a positive control to assess assay conditions.

Yeast transformation.

The yeast strains were transformed with the respective plasmids via a standard electroporation protocol for yeast transformation (2). Briefly, a single colony was grown in YPD (yeast extract-peptone-dextrose) medium at 30°C overnight, and this culture was added to 500 ml of prewarmed YPD and grown at 30°C to an optical density at 600 nm of 1.3 to 1.5 (about 12 to 15 h). The yeast were centrifuged, washed with double-distilled water (ddH2O), and resuspended in electrocompetence buffer (10× Tris-EDTA [TE], 10× lithium acetate, 250 mM dithiothreitol) at 30°C for 45 min. The electrocompetent yeast cells were harvested by centrifugation, washed (ddH2O), and resuspended in ice-cold 1 M sorbitol. The yeast cells were then aliquoted (40 μl) into 0.2-μm electroporation cuvettes containing 100 ng of total DNA and pulsed with the Bio-Rad Gene Pulser at 1.5 kV, 25 μF, and 200 Ω. Finally, the yeasts were plated onto respective minimal medium plates supplemented with the appropriate amino acids and incubated at 30°C for 1 to 2 weeks before being used in β-galactosidase assays.

Colony lift and liquid β-galactosidase quantitative assays.

The yeast colonies that grew following transformation were subjected to the colony lift β-galactosidase assay. Each plate was overlaid with a Whatman no. 5 filter disc, creating a replica of the plate, and the discs were then frozen in liquid nitrogen for 10 s and incubated at 30°C in 2 ml of Z-buffer (100 mM Na2HPO4, 40 mM NaH2PO4, 10 mM KCl, 1 mM MgSO4, 0.27% β-mercaptoethanol [BME]) containing 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (X-Gal) (18). Positive protein-protein interactions were identified by the presence of blue yeast colonies. The colonies became blue between 2 and 16 h of incubation at 30°C, depending upon the relative affinities of the protein interactions. Quantitative analyses were then conducted by a liquid β-galactosidase assay. Briefly, the suspected positive colonies were grown overnight at 30°C in minimal medium lacking the appropriate amino acids. A 2-ml aliquot of the overnight culture was inoculated in 8 ml of warm YPD and incubated at 30°C for 3 to 5 h until an optical density (600 nm) of 0.5 to 1 was reached. A 1.5-ml aliquot of the culture was then centrifuged, resuspended in Z buffer, frozen in liquid nitrogen (45 s), and supplemented with o-nitrophenyl β-d-galactopyranoside (ONPG). The reaction mixtures were incubated at 30°C for 1 to 3 h to develop a yellow color, and absorbance at 420 nm was measured to calculate the nanomoles of ONPG hydrolyzed per minute.

Purification of GST fusion proteins.

The expression and purification of GST fusion proteins were carried out as described previously (33, 34) with slight modifications. Competent BL21(DE3)pLysE E. coli was transformed with the pGST-EICP22 expression plasmid, and colonies were inoculated into 2× YT (yeast tryptone) medium supplemented with 2% glucose and 100 μg of ampicillin per ml and incubated overnight with shaking at 37°C. The cultures were diluted 1:10 into 500 ml of fresh prewarmed 2× YT medium supplemented with 100 μg of ampicillin per ml and incubated at 37°C for 3 h. Isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactoside (IPTG) was added to a final concentration of 0.1 mM. After a 2-h incubation, the bacteria were harvested by centrifugation, resuspended in 20 ml of ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 0.25 mM aprotinin, and 0.25 mM leupeptin, and subjected to French press lysis at 4°C. The extracts were clarified by centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 10 min, and the resultant supernatant was incubated with 1 ml of a 50% slurry of glutathione-Sepharose 4B (Pharmacia, Piscataway, N.J.) that was previously equilibrated with cold PBS. After a brief centrifugation, the matrix was washed three times with 10 bed volumes of ice-cold PBS. The GST fusion proteins were eluted in 1 ml of glutathione elution buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8], 10 mM reduced glutathione).

In vitro transcription and translation.

The proteins were translated from the expression plasmids in vitro by using a TnT kit as recommended by the manufacturer (Promega; Madison, Wis.). All experiments involving the translated products were performed in parallel in the presence or absence (competition assays) of [35S]methionine-labeled proteins. Radioactive products were analyzed by SDS-PAGE, using standard procedures for both discontinuous and gradient gels as described previously (10, 11, 29). pPOLY(A)-luc (T7) (Promega) and pZeoSv/lacZ (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, California) were used as T7 expression plasmids to generate 35S-labeled luciferase and LacZ control proteins, respectively.

GST pull-down and competition assay.

GST, GST-EICP22P, GST-EICP22P(Δ) deletion mutants, and GST-gD (EHV-1 glycoprotein D) were prepared and purified as described above and subjected to the GST pull-down procedure outlined previously (38). The GST fusion proteins were incubated with equivalent amounts of the 35S-labeled in vitro-translated products in a final volume of 200 μl of NETN buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8], 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5% Nonidet P-40). After incubation for 45 min at room temperature with gentle-rocking, 20 μl of a 50% slurry of glutathione-Sepharose 4B was added, and the proteins were given an additional 45-min incubation. Finally, the beads were washed five times in NETN buffer, and the proteins were eluted and then loaded onto gels for SDS-PAGE followed by autoradiography. The competition assays were essentially the same except that unlabeled in vitro-translated proteins were used in addition to the 35S-labeled species.

Coimmunoprecipitation from in vitro transcription-translation.

The Promega rabbit reticulocyte lysate TnT kit was used for in vitro transcription and translation of genes of interest. The in vitro transcription-translation was carried out as described in the standard reaction protocol, in which luciferase and ddH2O were used as positive and negative control reactions, respectively. The proteins were 35S labeled for each identification, and a small aliquot of each reaction product was analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by autoradiography. The procedure as outlined (48) describes an in vitro protein-binding assay whereby the mixture of lysates is allowed to incubate for 1 h at 30°C in binding buffer (20 mM HEPES [pH 7.9], 50 mM KC1, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 10% glycerol) to allow protein complexes to form. The coimmunoprecipitations were performed as described previously (48) with anti-EICP22P specific antibodies (anti-TrpE-IR4 and pooled monoclonal antibodies [MAbs] J1 to J7) as well as anti-IEP peptide specific antibody and anti-IEP specific MAbs (9, 10). The protein-antibody complexes were removed by using protein-A Sepharose beads (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) followed by centrifugation. After washing to eliminate nonspecific precipitates, the proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and subsequent autoradiography and phosphorimager analyses.

Coimmunoprecipitation from infected-cell lysates.

Monolayers of L-M cells were infected with EHV-1 KyA at a MOI of 10. After attachment (1.5 h at 37°C), the inoculum was removed and replaced with methionine-free medium for 1 h. This medium was then replaced for an additional 8 to 10 h with medium containing [35S]methionine (50 μCi/ml). The monolayers were washed extensively with PBS, and the cells were harvested and lysed in RIPA buffer (150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 0.1% SDS, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 1.0% Nonidet P-40). Immunoprecipitations of both EHV-1 infected and mock-infected lysates were performed with the anti-TrpE-IR4 antiserum, pooled EICP22P mAbs J1 to J7, preimmune rabbit serum, or anti-IEP peptide antiserum as previously described (9, 29) and were followed by SDS-PAGE analyses on 4 to 15% Tris-HCl gradient gels and autoradiography and phosphorimager analyses. The MAbs specific for EICP22P were generated by methods described previously (9), and the mapping of the epitopes reactive with each monoclonal antibody will be described elsewhere.

Western immunoblotting and SDS-PAGE analysis.

Monolayers of L-M cells were infected with EHV-1 at a MOI of 10. Both mock-infected and 12-h EHV-1-infected monolayers were washed extensively in PBS and lysed in RIPA buffer as previously described (29). After solubilization of the viral and cellular proteins, samples were boiled in 2× Laemmli sample buffer before being subjected to SDS-PAGE. To help stabilize the potential dimers and multimeric complexes, dithiobis(succinimidylpropionate) (DSP or Lomant's reagent] (37) was added to some of the samples at a final concentration of 2.38 mM. DSP is a water-insoluble, homobifunctional N-hydroxy succimide ester that targets and reacts with primary amines located at the N terminus of proteins, forming a thiol-cleavable, covalent amide bond with a span size of 12 Å. The advantage of DSP as the cross-linker is that the cross-linking is easily dissociated upon boiling of the sample in 10% BME prior to SDS-PAGE (37). Following fractionation by SDS-PAGE, the proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes as described in detail elsewhere (28). After the transfer, immunoblotting was performed with anti-TrpE-IR4 antibody specific for EICP22P (1:10,000 dilution) as the primary antibody for 30 min (room temperature) in TBST buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 150 mM NaCl, 0.05% Tween 20), and the mixture was given three 10-min washes in TBST. After washes to remove unbound primary antibody, alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat-anti rabbit antibody (Sigma) was added in TBST at a dilution of 1:7,000 for 30 min at room temperature, and the mixture was given three washes in TBST. Proteins were visualized by incubation in AP buffer (0.1 Tris-HCl [pH 9.5], 0.1 M NaCl, 5.0 mM MgCl) containing nitroblue tetrazolium (0.33 mg/ml; Life Technologies) and 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate (0.165 mg/ml; Life Technologies).

Laser-scanning confocal microscopy.

Equine ETCC cells were seeded on two-chamber glass slides (Nalge Nunc International, Naperville, Ill.) and infected with EHV-1 KyA. At the appropriate times postinfection, the cells were fixed in methanol at −20°C for 10 min, rehydrated in PBS for 10 min, blocked with 10% normal goat serum in PBS for 30 min, and reacted with a 1:200 dilution of a MAb to IEP or a 1:200 dilution of a polyclonal antibody to EICP22P in PBS with 1% bovine serum albumin for 3 h. After being rinsed, the cells were reacted with a tetramethylrhodamine-5-isothiocyanate (TRITC)-conjugated anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) or a fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG for 1 h. The slides were mounted in glycerol containing 0.1% p-phenylenediamine and 10% PBS and examined under a laser-scanning confocal microscope (MRC600; Bio-Rad Laboratories). Images were projected by use of the Bio-Rad Laboratories COMOS software and INDEC Microvoxel software.

RESULTS

EICP22P forms multimeric complexes during EHV-1 infection.

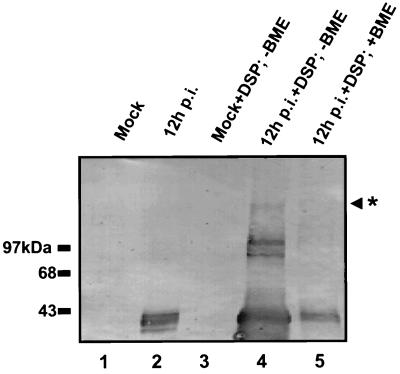

Previous studies showed that EICP22P is an early-gene product synthesized 3 to 4 h postinfection and migrates as a 42- to 47-kDa family of proteins on SDS-PAGE gels (28). Additionally, 32P-labeling experiments revealed that EICP22P is phosphorylated at both early and late times during infection (Bowles and O'Callaghan, unpublished). To address whether EICP22P multimerizes during infection, Western blot analyses with anti-TrpE-IR4 (EICP22P-specific) antiserum were performed on extracts of mock-infected and EHV-1-infected L-M cells at 12 h postinfection (Fig. 1). A family of proteins migrating between 42 and 47 kDa, indicative of EICP22P in monomeric form, was readily detected in infected cells (Fig. 1, lane 2). This family of proteins was not observed in the mock-infected cells (lanes 1 and 3), indicating the specificity of the anti-TrpE-IR4 antiserum. To examine the ability of EICP22P to form homocomplexes, the chemical cross-linker DSP was added to stabilize weak protein-protein interactions in separate aliquots of the 12-h lysates. As seen in the 12-h postinfection lane in which DSP was added but the sample was not boiled in 10% BME (lane 4), there appears to be an accumulation of EICP22P species that migrate between 85 and 100 kDa, which suggests the formation of EICP22P dimers. In addition, higher-molecular-mass species (125 to 140 kDa) were readily detected, indicating that higher-order complexes of EICP22P were formed (lane 4). The detection of these high-molecular-mass species in the infected cell extracts suggests that these proteins are EICP22P species, but the presence of proteins that are either nonspecifically cross-linked or “trapped” in these complexes has not been totally ruled out. Boiling the DSP cross-linked extracts in Laemmli sample buffer supplemented with 10% BME dissociated most of the multimeric EICP22P complexes to the monomeric form (lane 5). These data suggest that formation of EICP22P dimers and higher-order complexes occurs during EHV-1 infection.

FIG. 1.

Detection of multimeric complexes of EICP22P in extracts of EHV-1-infected cells. Mock-infected (lanes 1 and 3) and EHV-1-infected (lanes 2, 4, and 5) L-M cell extracts were prepared at 12 h postinfection (p.i.) as described in Materials and Methods. Western blot analysis of the extracts with anti-TrpE-IR4 antibody specific for EICP22P shows a family of proteins migrating between 42 and 47 kDa (lane 2). DSP was added to the extracts of mock-infected (lane 3) and infected (lanes 4 and 5) cells. Lane 4 shows the EICP22P species migrating at approximately 85 to 100 kDa. The asterisk indicates higher-order EICP22P complexes at approximately 125 to 140 kDa (lane 4). DSP-cross-linked infected-cell extracts were boiled in loading buffer containing 10% BME to dissociate the DSP-stabilized EICP22P complexes (lane 5).

EICP22P forms complexes with IEP and self-aggregates in yeast two-hybrid analyses.

To investigate further the possibility that EICP22P undergoes physical interactions with itself as well as with IEP, the full-length EICP22 and IE ORFs were cloned next to the activation and DNA-binding domains of the yeast two-hybrid vectors as described in Materials and Methods. The positive control plasmids pACTGac-1 and pAS1-CYHPP-1, in which Gac-1 is a regulatory subunit of the yeast phosphatase type 1 known to physically associate strongly with the PP-1 protein (18), were used to assess assay conditions. Quantitative analyses were then conducted by a liquid β-galactosidase assay in which the relative strength of the protein-protein interaction was determined by measurement of the rate of hydrolysis of ONPG. The results (Table 1) clearly indicate that a physical interaction occurred between EICP22P and IEP and that EICP22P undergoes self-aggregation. Other control reactions tested possible protein-protein interactions, including EICP22P–Gac-1, EICP22P–PP-1, IEP–Gac-1, and IEP–PP-1, and the results revealed that these EHV-1 regulatory proteins did not interact with either of the yeast proteins. In these control reactions, all values of ONPG hydrolysis were at background levels (<80 nmol of ONPG hydrolyzed). Additionally, the lack of false-positive results when each plasmid was transformed alone ruled out endogenous activation by either EICP22P or IEP. As shown in Table 1, under the conditions used, EICP22P interacted with IEP with an apparently lower affinity than that with which EICP22P self-associates. In this strain of yeast (SFY526), the result that EICP22P self-interaction was of a greater affinity than was the interaction between EICP22P and IEP was reproducible in five independent assays. Lastly, the results indicate that EHV-1 IEP also undergoes a self-interaction.

TABLE 1.

Yeast two-hybrid analyses of plasmids expressing the EHV-1 IE and EICP22 genesa

| Bait | β-Galactosidase activityb of (prey):

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (no plasmid) | EHV-1 EICP22P | EHV-1 IEP | Control (Gac-1) | Control (PP-1) | |

| SFY 526 yeast | 16 | 13 | 14 | 14 | 20 |

| EHV-1 EICP22P | 24 | 18,720 | 1,330 | 40 | 61 |

| EHV-1 IEP | 30 | 1,210 | 880 | 45 | 79 |

| Control (Gac-1) | 19 | 21 | 29 | 69 | 48,200 |

| Control (PP-1) | 37 | 58 | 63 | 45,380 | 54 |

The EHV-1 EICP22 and IE genes were cloned into either the DNA-binding plasmid (bait) or the Gal4 activation domain plasmid (prey) and cotransformed into yeast strain SFY526 as outlined in Materials and Methods. The yeasts were cultivated overnight, and following fractionation, the samples were assayed for β-galactosidase activity by measurement of ONPG hydrolyzed as described in Materials and Methods.

Values shown are nanomoles of ONPG hydrolyzed. All negative controls yielded 80 nmol or less of ONPG hydrolyzed. The positive controls, Gac-1 and PP-1, yielded values as high as 48,200 nmoml of ONPG hydrolyzed. The data indicate that protein-protein interactions occurred between the EICP22P-EICP22P pair, the EICP22P-IEP pair, and the IEP-IEP pair. Thus, the EICP22P-IEP interaction was weak compared to that of the positive controls. The data in this table were reproducible, and similar findings were obtained in four additional independent assays.

Coimmunoprecipitation of a complex of EICP22P and IEP from in vitro transcription-translation lysates.

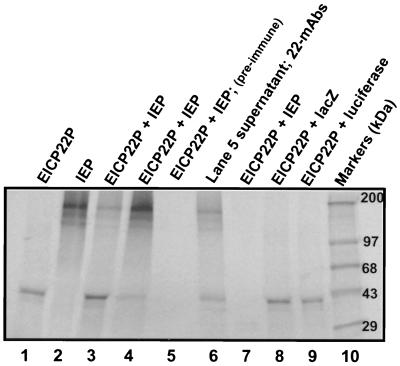

To assess whether the full-length EICP22P can physically interact with IEP by a more biochemical approach in which the proteins are readily expressed and detected, an in vitro transcription-translation system was used. Figure 2 shows the results of the coimmunoprecipitations from the in vitro transcription-translation reactions. Lanes 1 and 2 present single immunoprecipitations of EICP22P (lane 1) and IEP (lane 2) with anti-TrpE-IR4 polyclonal antiserum specific for EICP22P or anti-IEP peptide antiserum specific for IEP. The single-protein immunoprecipitations were performed to demonstrate the ability of each antibody to immunoprecipitate its respective protein in the unmixed lysates. Other control reactions, as well as our previous studies, showed that the antibody specific for EICP22P did not cross-react with IEP (28, 33) and that the antibody specific for EIP did not cross-react with EICP22P (9). The EICP22P-IEP physical interaction was assessed by the ability of either antibody to immunoprecipitate a complex of both radiolabeled protein species from a mixture of the incubated lysates. As shown in Fig. 2, lanes 3 and 4, protein species of 43 and 200 kDa, which correspond to the molecular masses of EICP22P and IEP, respectively, were immunoprecipitated by either the antibody specific for EICP22P or the antibody specific for IEP. A control reaction with preimmune rabbit serum (lane 5) failed to immunoprecipitate either protein. Also, an immunoprecipitation reaction with anti-EICP22P pooled MAbs J1 to J7 and the supernatant saved from the preimmune control (lane 5) yielded both EICP22P and IEP (lane 6). To further rule out nonspecific antibody cross-reactivity, an antibody specific for the RacC protein of Dictyostelium discoideum (54) failed to immunoprecipitate either EICP22P or IEP (lane 7). The antibody specific for EICP22P was unable to immunoprecipitate either the radiolabeled 116-kDa β-galactosidase protein (lane 8) or the 71-kDa luciferase protein (lane 9) from mixed lysates containing EICP22P and either one of these heterologous proteins. These observations indicate the specificity of the interactions of the EHV-1 proteins and further show that the antibodies to the two viral proteins do not mediate nonspecific cross-reactions with heterologous proteins.

FIG. 2.

Coimmunoprecipitation of IEP and EICP22P from in vitro transcription-translation reactions. The EICP22, IE, lacZ, and luciferase genes were cloned into T7 promoter-driven expression constructs and were in vitro transcribed-translated and [35S]methionine labeled with the Promega TnT rabbit reticulocyte lysate kit as described in Materials and Methods. Immunoprecipitations were performed with anti-TrpE-IR4 antibody specific for EICP22P (lanes 1, 3, 8, and 9) and pooled MAbs J1 to J7 specific for EICP22P (lane 6); anti-peptide IEP-specific antibody (lanes 2 and 4), preimmune rabbit serum (lane 5), and anti-RacC protein antibody (lane 7). Lanes 1 (EICP22P) and 2 (IEP) contain positive control immunoprecipitations to assess the ability of the antibody to each viral protein to immunoprecipitate its respective protein. In reactions where both EHV-1 protein extracts were mixed, both EICP22P and IEP were precipitated as a complex by antibody specific for either EICP22P or IEP (lanes 3, 4, and 6). Control immunoprecipitations with anti-TrpE-IR4 antibody specific for EICP22P were unable to precipitate either LacZ (lane 8) or luciferase (lane 9).

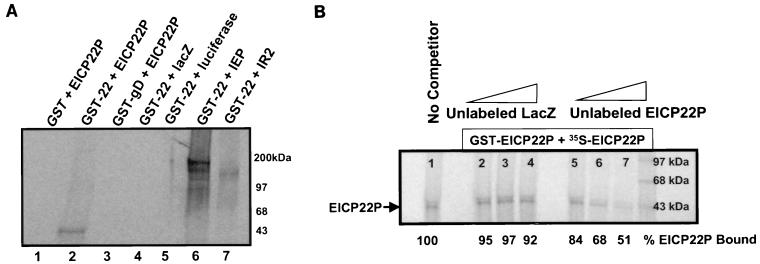

EICP22P interacts specifically with IEP and self-aggregates in GST pull-down studies.

To determine whether the EICP22P-IEP interaction and the EICP22P self-interactions indicated in the two-hybrid analysis are a result of a direct physical interaction between the proteins, in vitro protein-binding assays were performed. GST-tagged, full-length EICP22P was prepared and purified as described in Materials and Methods. Either GST, GST-gD, or GST-EICP22P was incubated with equivalent amounts of in vitro transcribed-translated [35S]methionine-labeled EICP22P, IEP, IR2P, luciferase, or LacZ in a final volume of 200 μl of NETN buffer, and pull-down assays were carried out as described previously (38). The autoradiographic results of the GST pull-down reactions (Fig. 3A) indicate that significant amounts of radiolabeled EICP22P were pulled down by the GST-EICP22P/Sepharose beads (Fig. 3A, lane 2) whereas neither the radiolabeled LacZ protein (lane 4) nor the radiolabeled luciferase protein (lane 5) was precipitated in appreciable amounts. Experiments assessing the ability of GST-EICP22P to precipitate either the radiolabeled IEP or the radiolabeled IR2P are shown in lanes 6 and 7, respectively. GST-EICP22P physically interacted with IEP and, to a lesser extent, with IR2P (compare the band intensities of lanes 6 and 7). Negative control reactions showed that neither GST (lane 1) nor GST-gD (lane 3) was able to precipitate the radiolabeled viral protein. Also, our previous findings (33, 34), as well as additional control reactions (results not shown), revealed that GST did not react with IEP. The failure of GST to interact with IEP is a reproducible finding as shown in the experiments in Fig. 8B. Furthermore, in competition assays in which either unlabeled in vitro-transcribed-translated EICP22P or LacZ was added prior to the addition of radiolabeled EICP22P, a reduction in the amount of radiolabeled EICP22P precipitated was observed only when the unlabeled EICP22P was added (Fig. 3B, compare lanes 2 to 4 with lanes 5 to 7).

FIG. 3.

EICP22P specifically interacts with itself and IEP. (A) GST pull-down assays. GST (lane 1) and GST fusion proteins GST-EICP22P (lane 2) and GST-gD (lane 3) were preincubated with in vitro-transcribed-translated 35S-EICP22P prior to precipitation with glutathione-Sepharose beads. Specific interactions between EICP22P and itself are evident in lane 2. The ability of 35S-IEP (200 kDa) and 35S-IR2P (125 kDa) to physically interact with GST-EICP22P is shown in lanes 6 and 7, respectively. Control reactions were performed with GST-EICP22P with 35S-LacZ (lane 4) or 35S-luciferase (lane 5). (B) Competition assays. GST-EICP22P was preincubated with either increasing amounts of unlabeled in vitro-transcribed-translated LacZ protein (lanes 2 to 4), or unlabeled in vitro-transcribed-translated EICP22P (lanes 5 to 7). The percentage of 35S-EICP22P bound by GST-EICP22P in the presence of each competitor, compared to the amount bound in the absence of a competitor, which was set at 100% (lane 1), is indicated under each lane. Preincubation with the unlabeled EICP22P, but not LacZ, reduced the amount of 35S-EICP22P precipitated (% EICP22P Bound).

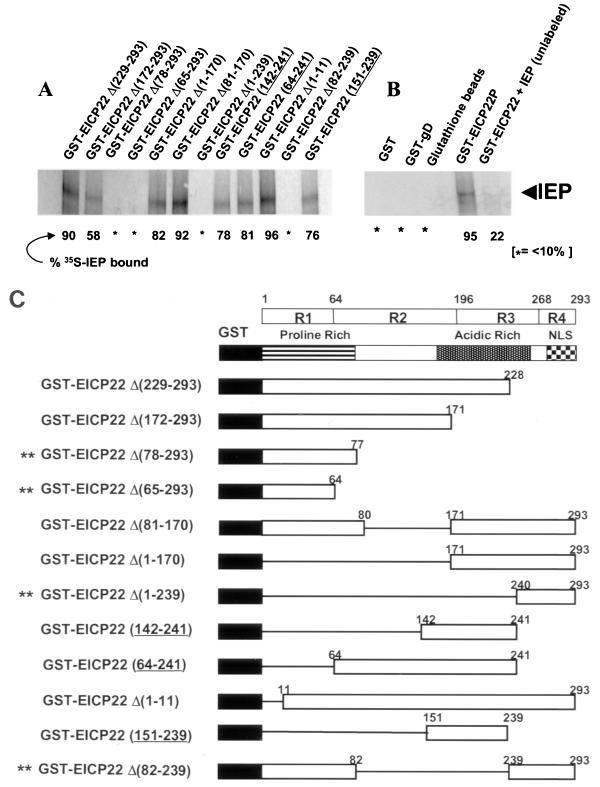

FIG. 8.

Physical interaction of EICP22P and IEP require sequences that map within regions 2 and 3 of EICP22P. (A) The panel of GST-EICP22P deletion and truncation mutants in panel C were prepared and purified as described in Materials and Methods. Each GST fusion protein was used in separate reactions as precipitators in GST pull-down assays with in vitro-transcribed-translated 35S-IEP products of the pGemIE expression construct. Following incubation, the complexes were removed via precipitation with glutathione-Sepharose beads, and the bound proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and subsequent autoradiography. The relative amounts of bound protein were calculated respective to the amount of 35S-IEP that was bound by the full-length GST-EICP22P (% 35S-IEP bound); 95% of the total cpm of 35S-IEP was bound by the GST-EICP22P fusion. Measurements of bound 35S-IEP were made by both phosphorimager analysis and scintillation counting of excised bands after solubilization. The asterisk indicates that less than 10% of the cpm of the 35S-IEP was bound. (B) Specificity of the interaction between 35S-IEP and GST-EICP22P. Neither GST, GST-gD, nor glutathione beads reacted with 35S-IEP. The GST-EICP22P protein bound 95% of the total cpm of 35S-IEP. Incubation of unlabeled in vitro-transcribed-translated IEP with GST-EICP22P prior to addition of 35S-IEP significantly reduced the percentage of 35S-IEP bound. (C) Diagram of the GST-EICP22P deletion mutants. The open box indicates the amino acid sequences of EICP22P present in each GST fusion protein. The double asterisk indicates the GST fusion proteins that failed to interact significantly with 35S-IEP.

EICP22P forms complexes with IEP during EHV-1 infection.

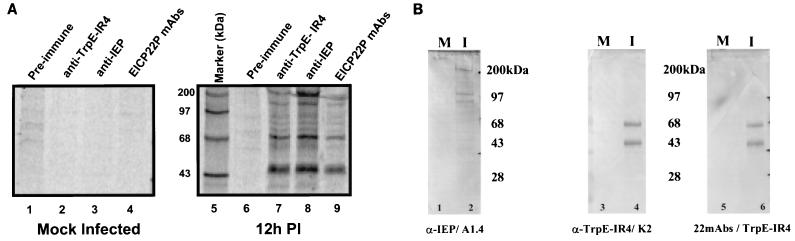

To examine the relevance of the EICP22P-IEP physical interactions, experiments were performed with EHV-1-infected cells to evaluate possible in vivo interactions of these two viral regulatory proteins. The results of coimmunoprecipitation analyses of both mock-infected (Fig. 4A, lanes 1 to 4) and 12-h EHV-1-infected (lanes 6 to 9) cell extracts were compared. Immunoprecipitations with the EICP22P-specific antibody resulted in the precipitation of proteins migrating at 43 and 200 kDa, corresponding to EICP22P and IEP, respectively (lanes 7 and 9). Immunoprecipitation with the IEP-specific antibody also resulted in the precipitation of both the 200-kDa IEP and significant amounts of the 43-kDa EICP22P (lane 8). In contrast, precipitation reactions of mock-infected cells (lanes 1 to 4) and precipitation reactions of infected cells with preimmune rabbit serum (lane 6) failed to exhibit significant amounts of the EHV-1 specific proteins. Furthermore, the results of the immunoprecipitations reveal the presence of a 68- to 70-kDa radioactive species in the infected cell extracts (lanes 7 to 9). Previous studies have shown that the EICP22 gene is transcribed as an early 1.4-kb and late 1.8-kb transcript (29, 30). The minor 1.8-kb transcript encodes a 469-aa form of EICP22P that has a predicted molecular mass of 68.8 kDa. To assess whether the 68- to 70-kDa radioactive species observed in the immunoprecipitations of EHV-1-infected cell extracts (Fig. 4A) is the 469-aa form of EICP22P, Western blot analyses were performed on aliquots of the respective immunoprecipitation products (Fig. 4B). As shown in Fig. 4B, a 68- to 70-kDa band was observed in Western blots with EICP22P specific primary antiserum but not in those with IEP specific primary antiserum. Additionally, the absence of this 68- to 70-kDa species in the mock-infected controls indicates that this species is not of cellular origin but is virus specific. Collectively, these data confirm the results of the experiments described above in which in vitro approaches were used, suggesting that the physical interactions between the two forms of EICP22P and IEP occur throughout EHV-1 infection.

FIG. 4.

(A) Coimmunoprecipitation of EICP22P and IEP from EHV-1-infected cell lysates. Mock-infected (lanes 1 to 4) and EHV-1-infected (lanes 6 to 9) L-M cells were radiolabeled with [35S]methionine as described in Materials and Methods. Cell lysates were prepared at 12 h postinfection (PI), and immunoprecipitations were performed. Aliquots of each extract were incubated with either preimmune rabbit serum (lanes 1 and 6), anti-TrpE-IR4 antibody specific for EICP22P (lanes 2 and 7), anti-peptide antibody specific for IEP (lanes 3 and 8), or pooled EICP22P-specific MAbs J1 to J7 (lanes 4 and 9). Immunoprecipitations of the EHV-1-infected lysates revealed radioactive species migrating at approximately 43 and 200 kDa with antibodies specific for either EICP22P or IEP. A radiolabeled band of approximately 68 to 70 kDa, indicative of the 469-aa form of EICP22P, was present in immunoprecipitates of EHV-1-infected extracts by using either EICP22P-specific (lanes 7 and 9) or IEP-specific (lane 8) antibody. The minor bands may represent protein degradation or incomplete translation products. (B) Western blot analyses of immunoprecipitations identify the 68- to 70-kDa band as an EICP22P species. Aliquots of coimmunoprecipitation reaction products from panel A were run on a separate SDS-PAGE gel and subjected to western blot analyses with IEP-specific MAb (A1.4) or EICP22P-specific MAb (K2) and polyclonal antibody (TrpE-IR4) as the primary antibody. The presence of the 68- to 70-kDa species was observed only in the infected (I) immunoprecipitates when the EICP22P-specific antisera were used as the primary antibody (lanes 4 and 6). Precipitates of mock-infected cells (M) with the EHV-1 specific antibodies were negative for any of the protein species.

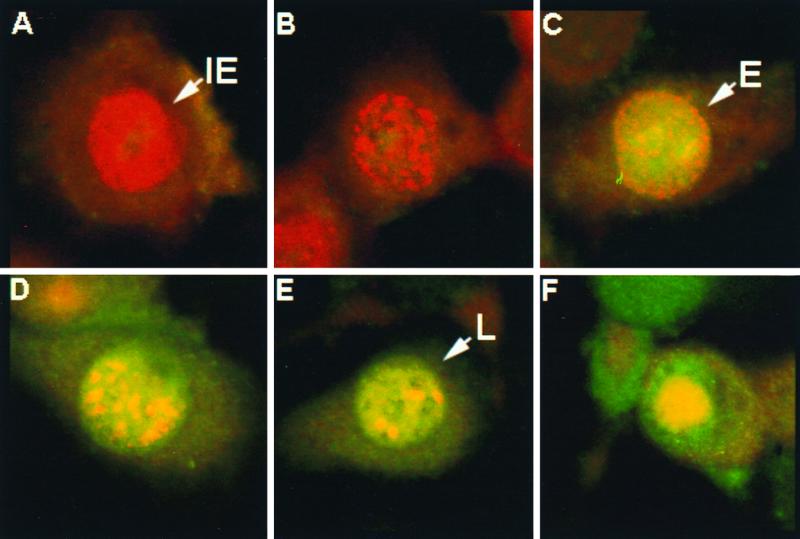

IEP and EICP22P colocalize in the nuclei of infected cells.

To determine whether IEP and EICP22P colocalize in infected equine ETCC cells, laser-scanning confocal microscopic analyses were performed with an anti-IEP-specific mouse monoclonal antibody (9) and an anti-EICP22P specific rabbit polyclonal antibody (28). IEP rapidly localized to the nucleus (Fig. 5A and B), and its distribution changed during the course of infection. Initially, IEP was dispersed throughout the nucleus (Fig. 5A), but thereafter it began to aggregate in small, dense structures within the nucleoplasm (Fig. 5B) (8). At early times (4 h) postinfection, EICP22P was initially dispersed throughout the nucleus while IEP was tightly aggregated in small, dense nuclear structures within the nucleoplasm (Fig. 5C). With time, IEP began to colocalize with EICP22P (Fig. 5C and D). At later times postinfection, the colocalization of the two EHV-1 proteins increased (Fig. 5E and F). These data are consistent with the observations that IEP and EICP22P physically interact.

FIG. 5.

Laser-scanning confocal microscopic analysis of the localization of IEP and EICP22P in EHV-1 infected cells. EHV-1-infected equine (ETCC) cells were fixed at 2 h (A), 3 h (B), 4 h (C), 6 h (D), and 16 h (E and F) postinfection. The cells were reacted with a 1:200 dilution of a mouse MAb to the IE protein (A1.4) and a 1:200 dilution of a rabbit polyclonal antibody to the EICP22P in PBS–1% BSA for 3 h. After extensive rinsing in PBS, the cells were reacted with a TRITC-conjugated anti-mouse IgG antibody (red) and a FITC-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG antibody (green) for 1 h and were examined under a laser-scanning confocal microscope as described in Materials and Methods.

Identification of amino acids required for EICP22P self-association by using yeast two-hybrid analysis.

The results of the above experiments revealed that a physical interaction occurs between EICP22P and itself (Table 1 and Fig. 3A). To determine the specific regions of EICP22P that mediate its self-interaction, EICP22 deletion mutants (Fig. 6) were subcloned into the activation domain of the yeast two-hybrid vector (pACTII-GAL4), as shown in Table 2. Plasmids pACT-IE and pACT-22 harbor the entire sequence of the IE and EICP22 genes, respectively. Each of these plasmids was cotransformed along with the full-length EICP22 ORF cloned into the GAL4 DNA-binding two-hybrid vector (pCYH-22) into the PJ-694A strain of yeast. The primary screen to identify transformants that express physically interacting EICP22P species was to determine whether the yeast transformants turned blue in the β-galactosidase plaque lift assay. Yeast strains harboring bait and prey plasmids that express the full-length EICP22P (pCHY-22 and pACT-22, respectively) or the Gac1 and PP-1 proteins were used as positive controls. All of the transformations resulted in colonies that grew on the minimal medium plates; however, the percentages of the growing colonies that became blue were dramatically different for the various mutants (Table 2). It is assumed that the transformants that did not become blue in the presence of X-Gal lacked a physical interaction between full-length EICP22P and that particular mutant EICP22P. None of the transformants pACT-M5, pACT-M6, and pACT-M7 yielded blue colonies (Table 2). These results were confirmed and quantitated by the liquid ONPG hydrolysis assays (Table 2). The finding that the ONPG hydrolysis levels of pACT-M5, pACT-M6, and pACT-M7 were below background indicated that a functional GAL4 transactivator was not present in these plasmids. Overall, analysis of the data with regard to which bait-prey pairs resulted in significant levels of ONPG hydrolysis indicated that the EICP22P sequences required for its self-interaction map between aa 124 and 150. Lastly, both the X-Gal plaque lift assay and the quantitative enzyme analysis confirmed that EICP22P and IEP physically interact (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Yeast two-hybrid mapping of EICP22P self-interactive sequencesa

| Bait plasmid | Prey plasmid | Deleted sequence (aa) | % of blue coloniesb | Amt (nmol) of ONPG hydrolyzed (SD)c |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pCYH-22 | pACT-IE | 65 | 18,035 (1,288) | |

| pCYH-22 | pACT-22 | 70 | 11,330 (1,122) | |

| pCYH-22 | pACT-M1 | 39–61 | 50 | 9,543 (1,077) |

| pCYH-22 | pACT-M2 | 81–92 | 45 | 11,297 (625) |

| pCYH-22 | pACT-M3 | 103–115 | 37 | 5,173 (822) |

| pCYH-22 | pACT-M4 | 81–124 | 20 | 4,153 (637) |

| pCYH-22 | pACT-M5 | 116–143 | 0 | 203 (23) |

| pCYH-22 | pACT-M6 | 143–150 | 0 | 480 (73) |

| pCYH-22 | pACT-M7 | 116–150 | 0 | 157 (25) |

| pCYH-22 | pACT-M8 | 272–290 | 64 | 10,400 (873) |

| pCYH-22 | pACT-IEP | 50 | 17,920 (1,220) | |

| pCYH–PP-1 | pACT–Gac-1 | 95 | 63,897 (3,885) |

Plasmid pCYH-22 and plasmid pCYH–PP-1 harbor the full-length EICP22 gene and the yeast phosphatase-1 gene, respectively, cloned into the GAL4 DNA-binding domain vector. Plasmids pACT-IE and pACT-IEP were independently generated plasmids that ahrbor the full-length IE gene in the GAL4 activation domain vector. Plasmid pACT-Gac-1 harbors the gene encoding the regulatory subunit of the yeast phosphatase 1 protein in the GAL4 activation domain vector. The various plasmid pairs were cotransformed into the PJ-694A strain of yeast, and the transformants were subjected to the β-galactosidase plaque lift assay. Colonies were obtained for each of the transformations, indicating that both plasmids were present. Selected transformants were subjected to the liquid β-galactosidase assay to assess the relative strengths of the interactions between EICP22P and each particular EICP22P deletion mutant. The details are given in Materials and Methods. In addition, single plasmid transformation with either the EICP22 or IE gene cloned into the DNA-binding vector to assess the ability of each EHV-1 protein to independently affect β-galactosidase expression failed to implicate these proteins as activators of the lac gene (data not shown).

The percentage of colonies that became blue within 6 to 8 h following plaque lift onto filters saturated with buffer containing X-Gal is indicated.

SD, standard deviation.

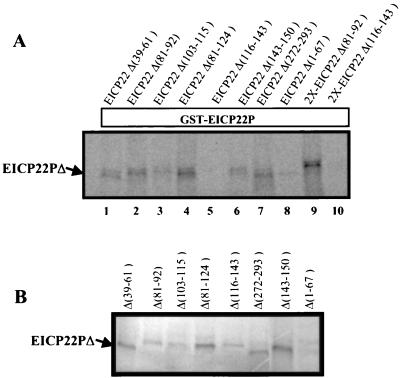

Identification of sequences that mediate the EICP22P self-interactions by using GST pull-down assays.

Results obtained with the yeast two-hybrid system implicated amino acids between 124 and 150 as the essential region for the EICP22P-EICP22P physical interaction. To confirm this result, a more biochemically defined protein-binding assay that demonstrates direct protein-protein interactions was used. The library of EICP22 deletion mutants (Fig. 6) was cloned into pGEM T7 promoter-driven plasmids and subjected to in vitro transcription-translation. Pilot experiments were performed to ensure that an adequate expression level of each radiolabeled mutant form of EICP22P was obtained and that each translation product was stable by subjecting a small aliquot of each reaction product to SDS-PAGE followed by autoradiography (Fig. 7B). The ability of each mutant protein to form higher-order complexes with GST-EICP22P was investigated by GST pull-down assays to determine the minimal EICP22P sequence that allow interaction with the full-length EICP22P. Autoradiographic results revealing which radiolabeled EICP22P species were reactive with GST-EICP22P are shown in Fig. 7A. As seen in lane 5, the EICP22P mutant lacking aa 116 to 143 failed to bind to the GST-EICP22P fusion. Additionally, doubling the amount of this EICP22P deletion mutant did not result in any significant binding of this EICP22P mutant to the GST-EICP22P (lane 10). Finally, an EICP22P mutant lacking aa 116 to 150 also failed to be precipitated by GST-EICP22P (data not shown), confirming the results of the yeast two-hybrid analyses (Table 2, pACT-M7). Further analyses of the EICP22P species indicated that deletion of EICP22P residues in the amino-terminal portion (lanes 1 to 4) or in the carboxy-terminal portion (lanes 6 and 7) failed to prevent the self-interaction, consistent with the conclusion that aa 124 to 143 are important for oligomerization of EICP22P. These data support the results obtained in the yeast two-hybrid screen with the EICP22P deletion mutants (Table 2).

FIG. 7.

Mapping amino acid sequences essential for the self-interaction of EICP22P by GST-EICP22P pull-down analysis. (A) GST pull-down analyses. Plasmids expressing portions of the EICP22 gene shown in Fig. 6 were in vitro transcribed-translated and radiolabeled with [35S]methionine as described in Materials and Methods. Equal amounts of each radiolabeled species were preincubated with the GST-EICP22P fusion, and precipitated with glutathione-Sepharose beads. The EICP22P deletion lacking aa 116 to 143 (lane 5) failed to interact with GST-EICP22P. Additionally, doubling the amount of this radiolabeled mutant protein resulted in no significant increase in in vitro binding (lane 10). (B) Expression of EICP22P deletion mutants. SDS-PAGE was performed with aliquots of products from the in vitro transcription-translation reactions of mutants depicted in Fig. 6 prior to GST pull-down analyses (A). All of the translation products were normalized to ensure that approximately equal amounts of each mutant were added in each GST pull-down reaction.

Identification of the EICP22P sequences required for the EICP22P-IEP physical interaction.

The interaction between the full-length EICP22P and the full-length IEP was demonstrated by in vivo (Fig. 4) and in vitro (Table 1 and Fig. 2) approaches. To map the EICP22P sequences required for its interaction with IEP, a diverse panel of GST-EICP22P mutants were used as precipitators in GST pull-down experiments. In this approach, an attempt was made to ascertain which of the GST fusion proteins that express portions of EICP22P could not precipitate full-length, [35S]methionine-radiolabeled IEP. Figures 8A and B show the autoradiographic results of the GST pull-down assays, and Fig. 8C is a diagram of the EICP22P sequences present in each GST-fusion protein. As shown, the percentage of 35S-IEP bound by the various GST-EICP22P deletion and truncation mutants varied considerably. The negative-control reactions showed that GST, glutathione beads, or GST–EHV-1 glycoprotein D (GST-gD) exhibited only background levels of binding to 35S-IEP (Fig. 8B). These levels never exceeded 10% and usually were only 1 to 5% of the levels that reacted with the GST fusion protein expressing full-size EICP22P (GST-EICP22P [Fig. 8B]). Importantly, the specificity of the interaction of these two viral regulatory proteins was shown in competition assays in which preincubation of unlabeled IEP with GST-EICP22P greatly reduced the binding of 35S-IEP (Fig. 8B, compare lanes 4 and 5). Other reactions showed that constructs that express EICP22P sequences 142 to 241, 64 to 241, or 151 to 239 significantly interact with IEP (78, 81, and 76% cpm of 35S-IEP bound, respectively), indicating that sequences mapping at the amino-terminal and carboxy-terminal portions of EICP22P are not essential for its interaction with IEP. Other reactions revealed that amino acids that span portions of region 2 (residues 65 to 196) and region 3 (residues 197 to 268) of EICP22P appear to encompass the IEP interaction site. These regions are delineated in the diagram shown in Fig. 8C.

DISCUSSION

We previously identified EICP22P as a homolog of ICP22P of HSV-1 and showed that it is an early auxiliary regulatory protein that enhances the transactivation activity of other EHV-1 regulatory proteins (28–30). EICP22P lacks DNA-binding motifs (29), has no in vitro DNA-binding activity (33), and in the absence of other EHV-1 regulatory proteins exhibits very minimal levels of activity in transient-transactivation assays (30). These initial observations led to the investigations of other possible mechanisms by which EICP22P can elicit its functions of transactivation synergy with other EHV-1 regulatory proteins. Recent findings from gel shift assays revealed that EICP22P greatly enhances the ability of IEP to bind to its own promoter as well as to promoters representative of all classes of EHV-1 genes (33). In addition, EICP22P enhances the rate of DNA binding of EHV-1 IEP (33) and the capacity of HSV-1 ICP4P to bind to its promoter (Kim and O'Callaghan, unpublished). These observations led to the speculation that EICP22P physically interacts with these viral regulatory proteins to mediate its synergistic effects on viral gene expression.

Results of experiments presented here, which used a variety of assays to assess protein-protein interactions, established that EICP22P physically associates with itself and with IEP. Additionally, our earlier work has shown that EICP22P is an auxiliary regulatory protein that enhance the expression of both early and late EHV-1 genes and can act in concert with either IEP EICP27P, or EICP0P of EHV-1 (3, 30, 33, 34). The physical interaction between EICP22P and IEP may help stabilize the interaction between IEP and its cognate promoter sites and/or may serve to enhance the attraction of components of the transcription initiation complex. The increased stability of these protein complexes is believed to contribute to the enhanced transactivation and DNA-binding levels of IEP in the presence of EICP22P. This type of interaction may be similar to that of the human T-cell lymphoma virus type 1 (HTLV-1) Tax transactivator-protein and CREB (cyclic AMP response element-binding protein) (59), which enhances HTLV-1 transactivation. Although the HTLV-1 Tax protein, like EICP22P, has no intrinsic DNA-binding activity (20, 40), it can increase the DNA-binding activity of certain bZip (basic leucine zipper) proteins by causing them to dimerize (5, 17, 21, 43, 61). It is not known whether EHV-1 EICP22P promotes the DNA-binding activity of cellular factors, and comparison to the well-characterized Tax protein is purely speculative at this point in the characterization of the EICP22P physical interactions.

Other results of the present study indicate that there is a self-aggregation of EICP22P both in vitro and in EHV-1-infected cells. The significance of these observations may be that dimerization of EICP22P facilitates its ability to stabilize IEP-DNA complexes and possibly that multimerization of EICP22P is requisite for its incorporation into the EHV-1 virion. It has been shown in studies of the HTLV-1 Tax protein that dimerization is required for it to associate with CREB and to be incorporated into the Tax-CREB-DNA ternary complex (60). Dimerization (or multimerization) of EICP22P may allow it to associate with IEP in a manner that fosters conformational changes of IEP and thereby enhances its interactions with cellular transcription factors. Another possibility is that EICP22P dimerization will elicit IEP dimerization such that IEP DNA-binding domains are positioned to allow multiple contacts with the IEP-binding site(s) within the promoter. This could result in the formation of a more stable clamp that IEP forms around the DNA-binding site. These two possible scenarios are representative of numerous possible models to explain the interactions between these two viral regulatory proteins.

Experiments presented here have identified physical interactions between IEP and multiple forms of EICP22P. Previous studies indicated that the late 1.8-kb EICP22 transcript potentially encodes a 469-aa protein species that has a predicted molecular mass of 68.8 kDa that was barely detectable at early times during infection (28). In the coimmunoprecipitation studies of EHV-1-infected cells, the 68-kDa species was precipitated in substantial quantities during late times postinfection (Fig. 4A) but in trace amounts at early times after infection (results not shown).

Studies with mutated forms of EICP22P indicate that the region essential to mediate the EICP22P-EICP22P self-interaction lies within aa 124 to 143. Protein sequence analyses, including BLAST and MotifFinder searches, of this portion of EICP22P have not identified a known motif that would readily mediate protein-protein interactions. A protein kinase C phosphorylation motif maps at aa 130 to 132, but it is not known whether EICP22P is phosphorylated at this specific site. It may be of interest to investigate this locus as a possible phosphorylation site as well as to examine the role that phosphorylation may play in EICP22P self-interaction. Further investigations with various EICP22P deletion and truncation mutants revealed that sequences within region 2 (aa 65 to 196) and region 3 (aa 197 to 268) of EICP22P mediate the interaction of EICP22P with IEP. Interestingly, other computer searches such as ProSite identified domains with a similar amino acid sequence in families of proteins such as the Ets-domain proteins (35), surfactant-associated polypeptide SP-C (31), and high mobility group 1 (HMG-1) DNA-binding domain proteins (6). Of these classes of proteins, the HMG-1 family is of interest because many of its members function in transcriptional regulation of various genes. Recent investigations revealed that the HMG-1(Y) protein modulates the binding of HSV-1 ICP4P to its cognate promoter (7, 44).

Our studies on the nature of the EHV-1 defective interfering particles (DIP) capable of mediating a state of persistent infection (41, 50) revealed that the DIP genome harbors repeated copies of a unique hybrid ORF that encodes the amino-terminal 196 aa of EICP22P and the carboxy-terminal 68 aa of EHV-1 EICP27P (13). This hybrid ORF, which encodes portions of two major EHV-1 early regulatory proteins, is abundantly expressed at both the mRNA and protein levels in cells infected with virus preparations containing DIP (13). More recent investigations demonstrated that expression of the EICP22P-EICP27P hybrid significantly alters EHV-1 gene expression (12). Expression of the hybrid protein significantly reduced expression of the IE gene promoter and early-gene promoters and altered the regulatory function of IEP and EICP22P. Since the highly expressed hybrid protein harbors EICP22P sequences mapping at residues 1 to 196, a sequence that encompasses the domain that mediates the EICP22P self-interaction and a portion of the domain that mediates the interaction of the EICP22P-IEP, it is possible that the hybrid protein alters viral gene expression by competing with EICP22P for interaction with itself and/or IEP. Such a reduction in the formation of complexes between EICP22P and IEP in cells persistently infected with EHV-1 may explain the observed inhibition in IE gene expression and the impairment in the function of IEP and EICP22P.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Suzanne Zavecz for excellent technical assistance and Martin Muggeridge, Arthur Frampton, Dawn Bowles, and Patrick Smith for helpful discussion. We thank Kelly Tatchell for the yeast strains and parent plasmids for the yeast two-hybrid studies. We also thank Robert Specian for assistance with the laser-scanning confocal microscopy.

This investigation was supported by research grant AI-22001 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. W.A.D. was supported by an NIH Research Supplement to Underrepresented Minorities Award.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allen G P, Bryans J T. Molecular epizootiology, pathogenesis, and prophylaxis of equine herpesvirus type 1 infections. Prog Vet Microbiol Immunol. 1986;2:78–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K. Current protocols in molecular biology. 1, 2, and 3. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bowles D E, Holden V R, Zhao Y, O'Callaghan D J. The ICP0 protein of equine herpesvirus 1 is an early protein that independently transactivates expression of all classes of viral promoters. J Virol. 1997;71:4904–4914. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.7.4904-4914.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brady J, Jeang K T, Duvall J, Khoury G. Identification of p40x-responsive regulatory sequences within the human T-cell leukemia virus type I long terminal repeat. J Virol. 1987;61:2175–2181. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.7.2175-2181.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bruni R, Roizman B. Herpes simplex virus 1 regulatory protein ICP22 interacts with a new cell cycle-regulated factor and accumulates in a cell cycle-dependent fashion in infected cells. J Virol. 1998;72:8525–8511. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.11.8525-8531.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bustin M, Reeves R. High-mobility-group chromosomal proteins: architectural components that facilitate chromatin function. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 1996;54:35–100. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)60360-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carrozza M J, DeLuca N A. The high mobility group protein 1 is a coactivator of herpes simplex virus ICP4 in vitro. J Virol. 1996;76:6752–6757. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.8.6752-6757.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carter K L, Roizman B. The promoter and transcriptional unit of a novel herpes simplex virus 1 alpha gene are contained in, and encode a protein in frame with, the open reading frame of the alpha 22 gene. J Virol. 1996;70:172–178. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.1.172-178.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caughman G B, Lewis J B, Smith R H, Harty R N, O'Callaghan D J. Detection and intracellular localization of equine herpesvirus 1 IR1 and IR2 gene products by using monoclonal antibodies. J Virol. 1995;69:3024–3032. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.5.3024-3032.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Caughman G B, Robertson A T, Gray W L, Sullivan D C, O'Callaghan D J. Characterization of equine herpesvirus type 1 immediate early proteins. Virology. 1988;163:563–571. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(88)90297-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Caughman G B, Staczek J, O'Callaghan D J. Equine herpesvirus type 1 infected cell polypeptides: evidence for immediate-early/early/late regulation of viral gene expression. Virology. 1985;145:49–61. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(85)90200-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen M, Garko K A, Zhang Y, O'Callaghan D J. The defective interfering particles of equine herpesvirus 1 encode a, ICP22/ICP27 hybrid protein that alters viral gene regulation. Virus Res. 1999;59:149–164. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1702(98)00128-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen M, Harty R N, Zhao Y, Holden V R, O'Callaghan D J. Expression of an EHV-1 ICP22/CP27 hybrid protein encoded by defective interfering particles associated with persistent infection. J Virol. 1996;70:313–320. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.1.313-320.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crab B S, Studdert M J. Equine herpesviruses 4 (equine rhinopneumonitis virus) and 1 (equine abortion virus) Adv Virus Res. 1995;45:153–190. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3527(08)60060-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cullinane A, Rixon F J, Davison A J. Characterization of the genome of equine herpesvirus 1 subtype 2. J Gen Virol. 1988;69:1575–1590. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-69-7-1575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davison A J, Scott J E. The complete DNA sequence of varicella-zoster virus. J Gen Virol. 1986;67:597–611. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-67-9-1759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feebler B K, Pascal's H, Kleinman-Ewing C, Wong-Staal F, Pavlakis G N. The pX protein of HTLV-1 is a transcriptional activator of its long terminal repeat. Science. 1985;229:675–679. doi: 10.1126/science.2992082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Francois J M, Thompson-Jaeger S, Skroch J, Zellenka U, Spevak W, Tatchell K. GAC1 may encode a regulatory subunit for protein phosphatase type 1 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 1992;11:87–96. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05031.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garko-Buczynski K A, Smith R H, Kim K S, O'Callaghan D J. Complementation of a replication defective mutant of equine herpesvirus 1 by a cell line expressing the immediate early protein. Virology. 1998;248:83–94. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Giam C Z, Xu Y L. HTLV-1 tax gene product activates transcription via preexisting cellular factors and cAMP responsive element. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:15236–15241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goren I, Semmes O J, Jeang K T, Moelling K. The amino terminus of Tax is required for interaction with the cyclic AMP response element binding protein. J Virol. 1995;69:5806–5811. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.9.5806-5811.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gray W L, Baumann R P, Robertson A T, Caughman G B, O'Callaghan D J, Staczek J. Regulation of equine herpesvirus type 1 gene expression: characterization of immediate early, early, and late transcription. Virology. 1987;158:79–87. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(87)90240-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gray W L, Baumann R P, Robertson A T, O'Callaghan D J, Staczek J. Characterization and mapping of equine herpesvirus type 1 immediate early, early, and late transcripts. Virus Res. 1987;8:233–244. doi: 10.1016/0168-1702(87)90018-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gray W L, Gusick N J, Ek-Kommonen C, Kempson S E, Fletcher T M. The inverted repeat regions of the simian varicella virus and varicella-zoster virus have a similar genetic organization. Virus Res. 1995;39:181–193. doi: 10.1016/0168-1702(95)00091-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harty R N, Colle C F, Grundy F J, O'Callaghan D J. Mapping the termini and intron of the spliced immediate-early transcript of equine herpesvirus 1. J Virol. 1989;63:5101–5110. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.12.5101-5110.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harty R N, Colle C F, O'Callaghan D J. Equine herpesvirus type 1 gene regulation: characterization of transcription from the immediate-early gene region in productive infection. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press, Inc.; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harty R N, O'Callaghan D J. An early gene maps within and is 3′ coterminal with the immediate-early gene of equine herpesvirus 1. J Virol. 1991;65:3829–3838. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.7.3829-3838.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Holden V R, Caughman G B, Zhao Y, Harty R N, O'Callaghan D J. Identification and characterization of the ICP22 protein of equine herpesvirus 1. J Virol. 1994;68:4329–4340. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.7.4329-4340.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Holden V R, Yalamanchili R R, Harty R N, O'Callaghan D J. ICP22 homolog of equine herpesvirus 1: expression from early and late promoters. J Virol. 1992;66:664–673. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.2.664-673.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Holden V R, Zhao Y, Thompson Y, Caughman G B, Smith R H, O'Callaghan D J. Characterization of the regulatory function of the ICP22 protein of equine herpesvirus type 1. Virology. 1995;210:273–282. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Johansson J, Curstedt T. Molecular structures and interactions of pulmonary surfactant components. Eur J Biochem. 1997;244:675–693. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.00675.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim S K, Bowles D B, O'Callaghan D J. The g2 late glycoprotein K promoter of equine herpesvirus 1 is differentially regulated by the IE and EICP0 proteins. Virology. 1999;256:173–179. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.9608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim S K, Holden V R, O'Callaghan D J. The ICP22 protein of equine herpesvirus 1 cooperates with the IE protein to regulate viral gene expression. J Virol. 1997;71:1004–1012. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.2.1004-1012.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim S K, Smith R H, O'Callaghan D J. Characterization of DNA binding properties of the immediate-early gene product of equine herpesvirus type 1. Virology. 1995;213:46–56. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Klemsz M J, Maki R A. Activation of transcription by PU1 requires both acidic and glutamine domains. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:390–397. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.1.390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leopardi R, Ward P L, Ogle W O, Roizman B. Association of herpes simplex virus regulatory protein ICP22 with transcriptional complexes containing EAP, ICP4, RNA polymerase II, and viral DNA requires posttranslational modification by the U(L)13 protein kinase. J Virol. 1997;71:1133–1139. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.2.1133-1139.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lomant A J, Fairbanks G. Chemical probes of extended biological structures: synthesis and properties of the cleavable protein cross-linking reagent [35S]dithiobis(succinimidyl propionate) J Mol Biol. 1976;104:243–261. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(76)90011-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Magnaghi-Jaulin H M L, Robin P, Lipinski M, Harel-Bellan A. SRE elements are binding sites for fusion protein EWS-FLI-1. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:1052–1058. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.6.1052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McGeoch J A D D, Donald S, Rixon R J. Sequence determination and genetic content of the short unique region in the genome of herpes simplex virus type 1. J Mol Biol. 1985;181:1–13. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(85)90320-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nyborg J K, Dynan W S, Chen I S, Wachsman W. Binding of host-cell factors to DNA sequences in the long terminal repeat of human T-cell leukemia virus type I: implications for viral gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:1457–1461. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.5.1457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.O'Callaghan D J, Henry B E, Wharton J H, Dauenhauer S A, Vance R B, Staczek J, Robinson R A. Equine herpesviruses: biochemical studies on genomic structure, DI particles, oncogenic transformation, and persistent infection. I. The Hague, The Netherlands: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, Inc.; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 42.O'Callaghan D J, Osterrieder N. Equine herpesviruses. 2nd ed. London, United Kingdom: Academic Press Ltd., Harcourt Brace & Co.; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Paca-Uccaralertkun S, Zhao L J, Adya N, Cross J V, Cullen B R, Boros I M, Giam C Z. In vitro selection of DNA elements highly responsive to the human T-cell lymphotropic virus type I transcriptional activator, Tax. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:456–462. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.1.456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Panagiotidis C A, Silverstein S J. The host-cell architectural protein HMG I (Y) modulates binding of herpes simplex type 1 ICP4 to its cognate promoter. Virology. 1999;256:64–74. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.9607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Post L E, Roizman B. A generalized technique for deletion of specific genes in large genomes: alpha gene 22 of herpes simplex virus 1 is not essential for growth. Cell. 1981;25:227–232. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90247-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Purves F C, Ogle W O, Roizman B. Processing of the herpes simplex virus regulatory protein alpha 22 mediated by the UL13 protein kinase determines the accumulation of a subset of alpha and gamma mRNAs and proteins in infected cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:6701–6705. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.14.6701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Purves F C, Roizman B. The UL13 gene of herpes simplex virus 1 encodes the functions for posttranslational processing associated with phosphorylation of the regulatory protein alpha 22. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:7310–7314. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.16.7310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ransone L J. Detection of protein-protein interactions by coimmunoprecipitation and dimerization. Methods Enzymol. 1995;254:491–497. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(95)54034-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rice S A, Long M C, Lam V, Schaffer P A, Spencer C A. Herpes simplex virus immediate-early protein ICP22 is required for viral modification of host RNA polymerase II and establishment of the normal viral transcription program I. J Virol. 1995;69:5550–5559. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.9.5550-5559.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Robinson R A, Vance R B, O'Callaghan D J. Oncogenic transformation by equine herpesviruses (EHV). II. Co-Establishment of persistent infection and oncogenic transformation of hamster embryo cells by EHV-I preparations enriched for defective interfering particles. J Virol. 1980;36:204–219. doi: 10.1128/jvi.36.1.204-219.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sakaguchi M, Urakawa T, Hirayama Y, Yamamoto M N M, Hirai K. Sequence determination and genetic content of an 89 kb restriction fragment in the short unique region and internal inverted repeat of Marek's disease virus type 1. Virus Genes. 1992;6:365–378. doi: 10.1007/BF01703085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schwyzer M, Wirth U, Vogt B, Fraefel C. BICP22 of bovine herpesvirus 1 is encoded by a spliced 17 kb RNA which exhibits immediate early and late transcription kinetics. J Gen Virol. 1994;75:1703–1711. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-75-7-1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sears A E, Halliburton I W, Meignier B, Silver S, Roizman B. Herpes simplex virus 1 mutant deleted in the a22 gene: growth and gene expression in permissive and restrictive cells and establishment of latency in mice. J Virol. 1985;55:338–346. doi: 10.1128/jvi.55.2.338-346.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Seastone D J, Lee E, Bush J, Knecht D A, Cardelli J. Overexpression of a novel Rho family GTPase, RacC, induces unusual actin-based structures and positively affects phagocytosis in Dictyostelium discoideum. Mol Biol Cell. 1998;9:2891–2904. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.10.2891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Smith R H, Caughman G B, O'Callaghan D J. Characterization of the regulatory functions of the equine herpesvirus 1 immediate-early gene product. J Virol. 1992;66:936–945. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.2.936-945.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Smith R H, Holden V R, O'Callaghan D J. Nuclear localization and transcriptional activation activities of truncated versions of the immediate-early gene product of equine herpesvirus 1. J Virol. 1995;69:3857–3862. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.6.3857-3862.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Smith R H, Zhao Y, O'Callaghan D J. The equine herpesvirus 1 (EHV-1) UL3 gene, and ICP27 homolog, is necessary for full activation of gene expression directed by an EHV-1 late promoter. J Virol. 1993;67:1105–1109. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.2.1105-1109.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Smith R H, Zhao Y, O'Callaghan D J. The equine herpesvirus type 1 immediate-early gene product contains an acidic transcriptional activation domain. Virology. 1994;202:760–770. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Suzuki T, Fujisawa J I, Toita M, Yoshida M. The trans-activator tax of human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 (HTLV-1) interacts with cAMP-responsive element (CRE) binding and CRE modulator proteins that bind to the 21-base-pair enhancer of HTLV-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:610–614. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.2.610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tie F, Adya N, Greene W C, Giam C Z. Interaction of the human T-lymphotropic virus type 1 Tax dimer with CREB and the viral 21-base-pair repeat. J Virol. 1996;70:8368–8374. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.12.8368-8374.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wagner S, Green M R. HTLV-I Tax protein stimulation of DNA binding of bZIP proteins by enhancing dimerization. Science. 1993;262:395–399. doi: 10.1126/science.8211160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zelnik V R, Darteil R, Audonnet J C, Smith G D, Riviere M, Pastorek J, Ross L N. The complete sequence and gene organization of the short unique region of herpesvirus of turkeys. J Gen Virol. 1993;74:2151–2162. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-74-10-2151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhang G, Laeder D P. The structure of the pseudorabies virus genome at the end of the inverted repeat sequences proximal to the junction with the short unique region. J Gen Virol. 1990;71:2433–2441. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-71-10-2433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhao Y, Holden V R, Smith R H, O'Callaghan D J. Regulatory function of the equine herpesvirus 1 ICP27 gene product. J Virol. 1995;69:2786–2793. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.5.2786-2793.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]