Abstract

Objective:

High salt intake is one of the leading diet-related risk factors for several non-communicable diseases. We aimed to estimate the prevalence of high salt intake in Iran.

Design:

A modelling study by the small area estimation method, based on a nationwide cross-sectional survey, Iran STEPwise approach to risk factor Surveillance (STEPS) 2016. The modelling estimated the prevalence of high salt intake, defined as a daily salt intake ≥ 5 g in all districts of Iran based on data from available districts. The modelling results were provided in different geographical and socio-economic scales to make the comparison possible across the country.

Setting:

429 districts of all provinces of Iran, 2016.

Participants:

18 635 salt intake measurements from individuals 25 years old and above who participated in the Iran STEPS 2016 survey.

Results:

All districts in Iran had a high prevalence of high salt intake. The estimated prevalence of high salt intake among females of all districts ranged between 72·68 % (95 % UI 58·48, 84·81) and 95·04 % (95 % UI 87·10, 100). Estimated prevalence for males ranged between 88·44 % (95 % UI 80·29, 96·15) and 98·64 % (95 % UI 94·97, 100). In all categorisations, males had a significantly higher prevalence of high salt intake. Among females, the population with the lower economic status had a higher salt consumption than the participants with higher economic status by investigating the concentration index.

Conclusions:

Findings of this study highlight the high salt intake as a prominent risk factor in all Iran regions, despite some variations in different scales. More suitable population-wide policies are warranted to handle this public health issue in Iran.

Keywords: Salt, Sodium chloride, Iran, Estimation, Spatial variation

Non-communicable diseases (NCD) have been the greatest contributor to mortality and disease burden globally, with growing trends during the recent decades(1). Various non-modifiable (e.g. age, gender and ethnicity) and modifiable (e.g. behavioural, social and cultural) risk factors have been blamed for the progression of the most prominent subcategories of NCD(2–4). As the major preventable determining factors of NCD, unhealthy diet, physical inactivity and tobacco use have attracted increasing attention(5). Unhealthy or suboptimal dietary habits have an important role in developing chronic NCD(6). In 2017, high Na intake, low whole grains intake and low fruit intake were the essential culprits for all-ages deaths and disability-adjusted life years globally(6). Hence, it seems imperative to implement suitable preventive strategies to stem the imposed burden of these risk factors.

High salt intake has been proved to be associated with numerous NCD development(5,7). Hypertension is one of the major affected conditions responsible for various CVD(8,9). Moreover, other potentially negative effects of high salt intake include increased risk of gastric cancer(10–12), kidney stones and osteoporosis(13,14), direct impact on stroke and left ventricular hypertrophy independent of hypertension(15,16), proteinuria and renal disease(17), asthma progression and exacerbation(18), and it is an indirect cause of obesity by increasing intake of fluids(19).

Diet-related NCD are growing rapidly in low- and middle-income countries, necessitating the implementation of urgent action plans to mitigate this trend(4,20). Investing in the prevention of NCD through financial and economic means is an effective method of stopping and managing the heavy burden of these diseases(21,22). Iran, a country within the Middle East region – a well-known area with vast socio-economic differences and inequities(23) – showed the highest rates of mortality and disability-adjusted life years attributable to high salt intake(24,25). A recent national report on salt intake in Iran represented that 97·66 % of the Iranian population consumes at least 5 g/d of salt. The mean salt intake among the population was 9·52 g/d (95 % CI 9·48, 9·56) in that survey(26). Also, a precious time-trend study on salt intake of the Iranian population exhibited an increasing trend of salt intake, especially with a significant increase in men, between 1998 and 2013(27). The undesirable dietary habits particularly high salt intake in Iran are nearly consistent with other countries located in the Middle East region, like the Arab countries and Turkey having noticeable population(3,28–31).

A successful action plan on handling high salt intake in populations starts with precise knowledge of salt intake in different geographic, economic and cultural domains of a country or region(5,32,33). Various studies around the world investigated spatiotemporal variations of salt intake(34–37). Besides, socio-economic status (SES) as a determinant of high salt intake has been studied in different countries(20,34,36–38). Although some studies examined salt intake in Iranian regions, it seems difficult to arrive at the best evidence-based decision concerning the current literature since the performed reports lack detailed data on all districts and regions(26). Therefore, in this study, we aimed to study socio-demographic differences of salt intake based on different geographical, social and economic aspects among districts of Iran. A thorough knowledge about variations of salt intake in different areas enables health authorities to introduce new policies to prevent high salt intake as a major risk factor for substantial NCD in countries like Iran.

Materials and methods

Data source and study population

We recruited the participants’ data from the Iran STEPwise approach to risk factor Surveillance 2016 study, based on 30 541 enrolled participants with 18 years old age and above. A cluster random sampling method of populations was done to enroll candidates from urban and rural populations of thirty provinces of Iran. The collected data covered 389 districts of Iran. Spot urine sampling – as a random urine sample – was obtained from all the candidates aged at least 25 years old. All collected samples were brought into the central headquarter of the survey in less than 18 h and analysed by one calibrated auto-analyser (Cobas C311 Hitachi High–Technologies Corporation) by the central committee(39). Three equations (Kawasaki, Tanaka and INTERSALT) were used to estimate daily salt intake from spot urine samples. The values derived from the Tanaka formula were set as the reference values since this method had the lowest root mean square error compared with others(40). Finally, a total number of 18 635 salt intake measurements from individuals were received and included by the central committee of the study(26). The difference between the present paper and the previously published one(26) is the more detailed investigation in this study by the chosen estimation model explained in the following sections. Iran is composed of thirty provinces, and each province consists of multiple districts. In the previous publication based on the Iran STEPwise approach to risk factor Surveillance 2016 survey, the values for high salt intake were reported for the participants chosen from provinces, and data were for the province level and reported at the individual level. Also, participants in that study were from 389 (out of 429) districts of Iran, and data for the remaining forty districts were not available. To meet this gap, we estimated the prevalence of high salt intake for all districts of Iran, and the provided data in this study are the aggregated data, not individual.

Study variables

High salt intake is the main variable of this study, defined as dietary guidelines of the WHO. The guideline mandates average daily consumption of sodium chloride (daily salt intake) less than 5 g for the general adult population of all countries except for regions that lower levels of salt intake have already been set based on prior investigations(41). We estimated the prevalence of high salt intake, defined as daily intake equal or more than 5 g, among all districts of Iran through the small area estimation method. The burden of high salt intake, defined as the number of populations in a district with a daily salt intake ≥ 5 g, was also estimated. All estimations were made for each sex separately. The utilisation of a salt shaker at the last meal was one of the questions in the STEPwise approach to risk factor Surveillance survey and was scored as a 1–5 scaling system by the participants. High scores of this question were determined as excess salt consumption variable to highlight the importance of self-report in salt intake.

Small area estimation method

To estimate spatial differences of salt intake in Iran, we used the small area estimation method, a statistical method utilised to estimate variables in areas with a small sample size and subpopulations of a smaller area within a larger geographical domain. We also stratified the population based on the two sexes in all districts of the country in 2016. Small areas due to small sample sizes may have imprecise estimations of variables. Therefore, various statistical methods have been suggested to generate valid and accurate statistics for these areas(42). Small area estimation methods are mainly based on generalised linear mixed models. A regression model encompassing covariates and correlated spatial errors dependent on near domains will help to make better estimations if a variable has a spatial dependence in small areas. This study utilised a Bayesian spatial hierarchical multilevel regression model for two levels of provincial and district estimations. The small area estimation model consists of two parts of a sampling model (#1) and a linking model (#2) as follows:

| (1) |

|

(2) |

where the

are the provinces and

are the provinces and

are the districts within each province,

are the districts within each province,

is the variance of the variable,

is the variance of the variable,

is the matrix of determining factors in the provincial level,

is the matrix of determining factors in the provincial level,

is the matrix of determining factors in the district level,

is the matrix of determining factors in the district level,

and

and

are the random effects of provincial and district levels respectively, which have a normal distribution, and

are the random effects of provincial and district levels respectively, which have a normal distribution, and

is the spatial random effect of near domains which has a conditional auto-regressive normal distribution(43). Adjacency matrix was utilised to input data from near districts in estimations, as the districts sharing a border weighted one and other components of the matrix weighted zero. This matrix was then introduced to the auto-regressive normal distribution of the random spatial effects model. Considering the variables’ prior distribution and likelihood distribution, the posterior distribution was calculated, and exports of data by sex and all districts were made based on the mean, and 2·5 and 97·5 percentiles of the variable were calculated correspondence as 95 % of uncertainty interval (UI). The prevalence of high salt intake for the rest of forty districts without data on salt intake was estimated through this model, and final results were reported for an overall number of 429 districts.

is the spatial random effect of near domains which has a conditional auto-regressive normal distribution(43). Adjacency matrix was utilised to input data from near districts in estimations, as the districts sharing a border weighted one and other components of the matrix weighted zero. This matrix was then introduced to the auto-regressive normal distribution of the random spatial effects model. Considering the variables’ prior distribution and likelihood distribution, the posterior distribution was calculated, and exports of data by sex and all districts were made based on the mean, and 2·5 and 97·5 percentiles of the variable were calculated correspondence as 95 % of uncertainty interval (UI). The prevalence of high salt intake for the rest of forty districts without data on salt intake was estimated through this model, and final results were reported for an overall number of 429 districts.

Spatial categorisations

Multiple categories of districts were generated to investigate differences of high salt intake in different areas. Comparisons between the four borders of Iran and areas by the seas were made. A previous survey in Iran classified all provinces in four main regions of the west, north-northeast, southeast and centrally based on geographical and SES to study metabolic risk factors of NCD(44). We also reported the prevalence of high salt intake among these super-regions of Iran.

Concentration index

The concentration index evaluated socio-economic variations and inequalities of salt intake. This index is calculated by the concentration curve. The concentration curve operates by a two-dimensional diagram composed of a health-associated variable (like salt intake in this study) and wealth index (as the socio-economic index). It visualises the status of the variable according to different economic categories. The wealth index was derived from household questionnaires assessing the SES. The principal components analysis method was used to aggregate data into the wealth index with five quintiles of poorest to richest categories(26,45). The horizontal axis of the diagram demonstrates the cumulative percentage of wealth index (poorest to richest levels), and the vertical axis demonstrates the high salt intake. A 45° bisector line of the diagram means equality of the estimated variable. Curves placed above the bisector line express a higher concentration of locations in poorer domains, and the concentration index will be negative. Curves placed under the bisector line mean higher concentrations in richer domains, and the concentration index will be positive(46). The concentration index in this study was derived from the Households Income and Expenditure Survey of Iranian households in 2016(47). As it was defined based on regional levels, inequality refers to a geographical difference of salt intake in this study.

Statistical analysis

UI were utilised to compare districts, as overlapping UI meant a non-significant difference in comparison. A P-value less than 0·05 was considered statistically significant. Due to the small sample size for various age groups of each sex and imprecise estimations on age categories, age-standardised estimations were reported only for the prevalence of high salt intake. However, estimations for all ages were done too and used to calculate the burden of high salt intake. Small area estimation modelling was carried out by the R2WinBUGS package in R for Windows version 3.6.1 (http://www.r-project.org/, RRID: SCR_001905) and OpenBUGS software. Visualisation was done by R for Windows version 3.6.1. Statistical analyses were performed using STATA version 11 (STATA Corp.).

Results

Overview

The prevalence of high salt intake was significantly higher in men than in women 94·80 % (95 % UI 89·15, 99·62), 86·50 % (95 % UI 74·94, 97·58), respectively, P-value < 0·001). The estimated Pearson correlation coefficient between high salt intake and related diet and lifestyle habits showed mild to moderate associations. The high salt intake had a positive correlation with using a salt shaker at the last meal (Pearson correlation coefficient 0·22, P-value < 0·001) and excess salt consumption (0·28, P-value < 0·001). This variable also negatively correlated with lifestyle modifications, including reducing salt consumption habits in estimations (-0·32, P-value < 0·001).

High salt intake in districts

Comparing the estimated prevalence of high salt intake among all districts of Iran beside their estimated mean of daily salt intake showed subnational trends of salt intake. Females in the Masal district of Gilan province had the lowest estimated prevalence of high salt intake as 72·68 % (95 % UI 58·48, 84·81), which imposed an estimated burden of 13 300 (11 371–15 163) with a mean salt intake of 7·99 (95 % UI 6·74, 9·30) g/d. In contrast, females in the Darmian district of South Khorasan province had the highest prevalence as 95·04 % (95 % UI 87·10, 100) alongside a burden of 13 047 (12 093–13 702) with a mean salt intake of 10·03 (95 % UI 8·32, 11·73) g/d. Males in the Abadan district of Khuzestan province earned the lowest estimated prevalence as 88·44 % (95 % UI 80·29, 96·15), imposing a burden of 79 059 (70 794–86 684) with a mean salt intake of 9·39 (95 % UI 7·73, 11·05) g/d. The highest prevalence of high salt intake in men happened in the Khorramdarreh district of Zanjan province as 98·64 % (95 % UI 94·97, 100), contributing to a burden of 21 976 (21 220–22 288), with a mean salt intake of 12·37 (95 % UI 11·01, 13·72) g/d (online supplementary material, Supplemental Table 1). The total estimated numbers of mean daily salt intake, the prevalence of high salt intake and compelled burden for all districts of Iran are available in online supplementary material, Supplemental Table 2.

Disparities of high salt intake

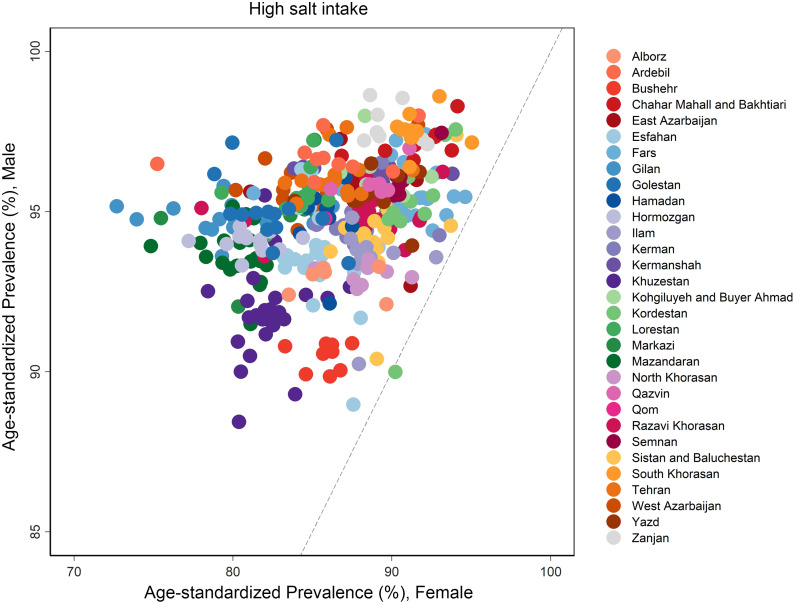

Patterns of high salt intake revealed a higher prevalence in males. Detailed visualisation of the age-standardised prevalence of high salt intake is provided in Fig. 1. Male to female ratio of estimated high salt intake ranged between 0·997 and 1·31. Only one district in the country had a ratio roughly lower than one (Kamyaran district in Kordestan province, 0·977). The mentioned ratio in 232 districts ranged between 1·01 and 1·10, ratios of 179 districts ranged between 1·10 and 1·20, ratios of sixteen districts ranged between 1·20 and 1·30, and only one district had a ratio more than 1·30 (Masal district in Gilan Province, 1·31) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Age-standardised prevalence of high salt intake in all districts of Iran, stratified by sex

Fig. 2.

Male to female ratio of the age-standardised prevalence of high salt intake compared in all districts of Iran

Various geographical and spatial variations of high salt intake were investigated. Districts sharing a border with other countries or seas/oceans (overall 113 districts) had a significantly lower high salt intake in comparison to non-border ones (316 districts) as 85·58 % (95 % UI 72·86, 97·50) v. 86·83 % (95 % UI 75·68, 97·60) in females (P-value = 0·004) and 94·23 % (95 % UI 87·94, 99·59) v. 95·01 % (95 % UI 89·58, 99·63) in males (P-value < 0·001). Districts located by the sea (forty-nine districts) had a lower prevalence of high salt intake in comparison to rest of districts (380 districts), as 82·44 % (95 % UI 68·10, 96·27) v. 87·03 % (95 % UI 75·82, 97·75) in females (P-value < 0·001) and 93·14 % (95 % UI 86·28, 99·40) v. 95·02 % (95 % UI 89·52, 99·65) in males (P-value < 0·001). Among provinces categorised in four main regions of the west, north-northeast, southeast and centrally, there was a significant difference between regions only in females, with the highest rates in the southeast region as 87·56 % (95 % UI 74·66, 99·14) v. the lowest in the north-northeast region as 83·85 % (95 % UI 71·59, 95·77) (P-value < 0·001). This regional categorisation showed no significant difference in males (P-value = 0·081). Females in districts located in the west border of Iran had a significantly lower prevalence of high salt intake as 87·48 % (95 % UI 76·18, 98·08) v. districts located in the east border as 90·00 % (95 % UI 78·43, 99·48) (P-value = 0·014). However, this difference was not significant in males of these two borders (P-value = 0·458). Districts located in the northern and southern borders of the country had significantly lower rates of high salt intake than districts of western and eastern borders for both sexes (P-value < 0·001). There were no significant differences between capital districts and non-capital districts among both males and females (Table 1).

Table 1.

Geographical disparities of high salt intake prevalence based on different categorisations of districts in Iran, stratified by sex

| Sex | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | Male | ||||||

| Geographical categorisation | Prevalence of high salt intake (%) | 95 % UI | P-value | Prevalence of high salt intake (%) | 95 % UI | P-value | |

| Border | Yes (113) | 85·58 | 72·86, 97·50 | 0·004 | 94·23 | 87·94, 99·59 | <0·001 |

| No (316) | 86·83 | 75·68, 97·60 | 95·01 | 89·58, 99·63 | |||

| Sea | Yes (49) | 82·44 | 68·10, 96·27 | <0·001 | 93·14 | 86·28, 99·40 | <0·001 |

| No (380) | 87·03 | 75·82, 97·75 | 95·02 | 89·52, 99·65 | |||

| Four regions | West (192) | 87·27 | 76·46, 97·72 | <0·001 | 94·95 | 89·39, 99·57 | 0·081 |

| North-northeast (88) | 83·85 | 71·59, 95·77 | 94·38 | 88·24, 99·73 | |||

| Southeast (66) | 87·56 | 74·66, 99·14 | 94·86 | 89·45, 99·72 | |||

| Central (83) | 86·69 | 75·16, 97·95 | 94·88 | 89·32, 99·52 | |||

| West v. East border | West (23) | 87·48 | 76·18, 98·08 | 0·014 | 94·94 | 88·99, 99·56 | 0·458 |

| East (19) | 90·00 | 78·43, 99·48 | 95·36 | 89·87, 99·93 | |||

| North and South v. West and East border | North-South (70) | 83·86 | 70·40, 96·89 | <0·001 | 93·69 | 87·09, 99·50 | <0·001 |

| West-East (42) | 88·62 | 77·20, 98·71 | 95·13 | 89·39, 99·73 | |||

| Capital v. non-capital districts | Capital (31) | 85·84 | 75·15, 96·16 | 0·340 | 94·93 | 89·90, 99·51 | 0·685 |

| non-capital (398) | 86·55 | 74·92, 97·69 | 94·79 | 89·09, 99·63 | |||

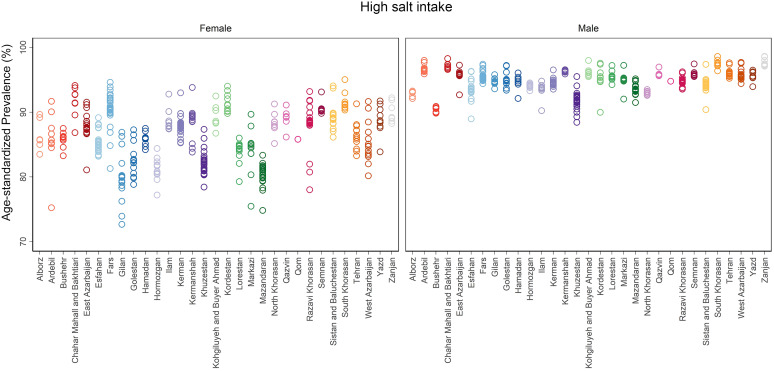

Differences of high salt intake between districts of each province indicated higher variation rates among females of districts than males. Except for Qom province, which has just one district, the highest and lowest disparity (the difference between maximum and minimum estimated prevalence) among females of districts was seen in Ardebil and Hamadan provinces, with differences of 16·5 and 3·3, respectively. The estimated differences between males were the highest in Kordestan (7·6) and the least in Kermanshah (0·7) provinces (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Disparities of age-standardised prevalence of high salt intake among districts of each province of Iran, stratified by sex

The estimated concentration index for high salt intake in females showed a significantly higher prevalence of this value in the poor population as −0·005 (95 % UI −0·008, −0·002). This index in males showed a higher prevalence of high salt intake in richer people as 0·001 (95 % UI −0·0006, 0·002), but the difference was not significant.

Discussion

We set out to highlight the high salt intake in all districts across Iran. High salt consumption was higher in males than females. Salt intake among females of different districts and regions showed significantly higher variations than males of the same regions. Districts located in borders and by the sea had a lower prevalence of high salt intake. Districts in western and eastern borders showed higher salt intake rates compared with northern and southern districts. The SES showed a minor impact on salt intake in Iran. Self-reported use of a salt shaker at the last meal and self-reported excess salt consumption were significantly correlated with a higher prevalence of high salt intake.

A drastic higher prevalence of high salt intake in men than women in almost all districts in Iran was observed. This finding was consistent with previous estimations and investigations of salt intake in the Iranian population(27,48,49). One study highlighted the possible role of a more prominent positive attitude towards lower salt consumption among women, especially in population with higher education(50). Previous studies have suggested the potential impact of sex differences like the menstrual cycle on lower salt preference and consumption(51,52). More participation of women in healthy eating habits like reading food labels, trying diets and a tendency to learn about nutrition and foods are other explanations(53,54). Other behavioural differences between men and women, like higher compliance with dietary guidelines and believing in instructions, and more profound concern about physical appearance and health issues in women, have lead women to more awareness of high salt intake(55).

Several geographical differences in high salt intake were reported in this study. Similar studies on spatial variations of high salt intake in Italy and the United Kingdom confirm the impact of regional differences on salt intake(34,36). A national survey in Italy showed significantly higher salt intake in the country’s southern regions(34). Similarly, a study in the UK found a north-south pattern of salt intake across Britain, and salt consumption was higher in Scotland than in England and Wales(36). High salt intake in districts located by the borders was lower than in other districts in Iran. The influence of cultures of neighbouring countries on diet habits, health beliefs and acculturation may have caused such differences(56,57). High salt intake was lower in districts alongside seas and oceans in this study. Other proposed explanations are consuming more fish and spicy food, which can potentially affect salt preference(26,58).

According to high salt intake estimations in the present study, a higher prevalence of high salt intake in females with poor SES was discovered based on the calculated concentration index. This is in line with previous investigations on the impact of socio-economic variations on salt intake in different countries, which have shown higher salt intake in lower social classes of populations(34,36,38). Researchers believe this finding is mainly due to the salty, fatty, low-quality, processed and cheap food products used in low socio-economic groups(59). In addition, low-quality bread is one of the main bases of diet in low socio-economic individuals. The bread produced with high percentages of salt is another interpretation of this issue(60). An investigation on 10 years of a national salt reduction initiative in Britain showed enduring social inequalities in salt intake even after the period of intervention(35). To conquer social inequalities of high salt intake, the implementation of proper educational programmes based on health education models is needed(38).

To explore insight on salt consumption, we evaluated the self-report use of salt shaker at the last meal. We found a moderate correlation between the high prevalence of high salt intake and excess use of salt shaker at meals in estimations. These findings support the importance of having insight into the high salt intake and its potential role in lowering extra salt intake. A previous large-scale study found that a brief questionnaire of eating behaviours named Salt Check Sheet could successfully predict salt intake in participants compared to laboratory measurements(61). Improving knowledge, perceptions and attitude on outcomes of high salt intake is another major step in controlling this issue(62). A study based on the theory of reasoned action revealed that attitude is the significant predictor of dietary habits, specifically high salt intake, and change in people’s attitude is essential in tackling this disaster(50).

In this study, a modelling method was used to estimate the prevalence of high salt intake in all districts of Iran. The estimated data could provide a precise vision for researchers and public health authorities to focus on areas with high salt intake more efficiently. The gold standard of salt intake measurement is Na excretion measurement in a 24-h urine sample(63). Alternative methods of urinary sodium estimation include random and timed spot urine samples. However, controversy remains on the validity of these methods, as various studies investigated the reliability of spot urine samples in estimating salt intake, and the results were not optimum(64,65). Therefore, to assess Na intake in an Iranian population, a combination of spot urine samples and a semi-quantitative FFQ method was developed and successfully employed. This method showed promising features in salt intake estimation(66).

Bread is an essential energy source, protein and vitamins and is widely used as a basic part of the diet globally(67). Iranians are the second greatest consumers of bread – after Turkey – in the world, with an average daily bread consumption of about 320 g, summing up to nearly 117 kg per capita annually(68,69). This amount of bread consumption is about 5 times of European countries and six times of global average bread consumption(69). One of the important sources of salt intake in the Iranian diet is bread, as salt is widely applied in bread preparation(68). The poor quality of bakery flour and lower protein content and gluten in flour are the major reasons for excessive use of salt in bread by bakers(68,70). So, bakers believe that adding salt helps to increase dough consistency and prevents the bread from sticking to surfaces(71). The standard salt level in bread is suggested to be less than 1 g in 100 g bread(72). Various studies in Iran investigated the amount of salt in different consumed bread in Iran. They revealed that the estimated salt amount in bread is 2–3 times higher than recommended levels, with this amount being higher in traditional bread than nontraditional types(68–70,73,74). Different community trials found that salt reduction in bread to one-half or one-third is feasible and has no significant impact on the taste or quality of bread(71,75). An alternative approach to reduce salt intake via bread without negative effects on bread sales is replacing sodium chloride with other salts like K-based salts(76,77). Also, the same consistency of dough can be provided by replacing excess salt with ascorbic acid(78,79).

The global estimates of salt intake in 2010 indicated that bread intake was twice as recommended globally, and areas with higher levels were East Asia, Central Asia and Eastern Europe(37). To tackle this issue worldwide, the WHO set a 30 % relative reduction in mean population salt intake as a goal before 2025 in the previous decade(80). WHO also introduced the SHAKE technical package, which consists of measuring and monitoring salt use, promoting food reformulation with lesser salt, inventing effective labelling and marketing tools, education, knowledge promotion and providing an environment that supports healthy eating(81). Successful national plans started in countries like the United Kingdom and Finland leading to significant control of salt intake in these countries. Plans included urging food industries to add less salt to foods, labelling food products and elevating public knowledge on high salt intake hazards(7). The idea rising from the UK resulted in a global programme of World Action on Salt and Health, translating the UK’s strategies and helping countries alongside the WHO to control high rates of salt intake(82). School-based educational programmes to reduce salt intake in students and their families (School-EduSalt) showed promising results, explicitly educating through social networks(83,84). The efficacy of population-level interventions in reducing dietary salt intake, especially focusing on reducing salt in bread, was also approved through some distinguished reviews(85,86).

Several community trials targeting high salt intake have been conducted in Iran. A reduction in high salt intake and blood pressure levels was achieved; however, larger studies at national levels are required(71,87,88). Healthy Bread Initiative was a part of the Healthy Food for Healthy Communities project in Esfahan province in Iran that provided new bread with no bicarbonate, less salt and more bran. The project was designed to enhance the behaviour of both producers and consumers of bread and resulted in a successful intervention towards salt intake reduction(89). Food labelling as traffic light labelling started as a national programme in 2014 and has been ruled to be obligatory for the food industry since 2016 in Iran(4,90). The efficacy and usefulness of food labelling have been studied and proved in Iran(91). However, more direct education like face-to-face instructions would help to better understand and notice the food labels(92,93). One survey investigated consumers’ negligence towards the use of food labels. Small sizes of information printed, lack of interest, uncertainty about information and failing to comprehend the labels were the main reasons for neglecting food labels in Iran(94). Policy analysis also showed that poor media involvement in public awareness, incompatibility of colours on labels with standard guidelines, inconsistency of label with nature of the product and lack of monitoring plans were the major obstacles against food labelling policies(95).

A successful national programme of salt intake reduction is comprised of four main steps: accurate estimation of the level of salt intake among all population as the first step, setting time-limited targets for salt intake by the population as the second step, developing and implementing interventions to reduce salt intake as the third step, and finally, monitoring and evaluation of the implemented programmes and making essential adjustments as the fourth step(5). In the process of designing and applying policies, there are four main target groups needed to be handled: decision-makers (policymakers and executive units), beneficiaries (general population, high-risk groups and medical staff), partners defined as anyone who can be involved in the process like media and religious authorities and potential oppositions (like food producers and providers)(32). Mandatory regulations and reformulations are undeniable parts of policies to reduce salt in food product preparations by food industries(96). Policies may face numerous barriers during the implementation process, but evidence-based solutions are ready to overcome them(97).

The limitations of this work are mainly complex modelling methods and possible statistical errors during estimations. Nevertheless, this is the first district-based study of salt intake in all Iran districts, which is the greatest strength of this work. Other limitations could be probable mistakes in salt intake measurements of included participants that was used as the base data for the modelling, which is out of the scope of this study as no new measurements were made for modelling. The lack of data on each age group of the population and area of residency is another limitation. Instead, age-standardised data were estimated to make the comparison between districts possible.

Conclusion

Regarding high salt intake in almost all districts of Iran, proper legislation and action plans are needed to stop this trend. Spatial variations of salt intake estimated in this study provide a beneficial measure for national and sub-national authorities and policymakers to handle this great public health issue in Iran.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to thank all the participants, researchers and staff of medical universities and Ministry of Health and Medical Education of Iran, which helped conducting the Iran STEPs 2016 survey. Also, we appreciate the aid of all colleagues in Non-communicable Diseases Research Center (NCDRC), and Endocrinology and Metabolism Research Institute, in Tehran University of Medical Sciences. Financial support: This research was funded by Iran’s Ministry of Health and Medical Education with the grant No. 1372. Conflict of interest: There are no conflicts of interest. Authorship: F.F. designed and conceptualised the study. S.A. interpreted the data and prepared the first manuscript. S.A., E.M. and A.A. did the literature search and review. E.G., A.G. and M.M. developed the small area estimation modelling codes and provided the results of modelling. N.E., S.A. and S.S.M. did the statistical analysis and visualisation. N.R., S.M.F., R.H. and F.G. had administrative support of the survey. A.K. and A.D.M. provided the data and had technical support. F.F., S.A., N.E., E.M., S.S.M., A.A. and N.R. critically revised the manuscript. All authors thoroughly read the final manuscript and approved the ultimate content and data. F.F. was the corresponding author and chief investigator of the study and supervised all stages of the survey. Ethics of human subject participation: This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki, and all procedures involving research study participants were approved by the ethical committee of Endocrinology and Metabolism Research Institute of Tehran University of Medical Sciences, under code IR.TUMS.EMRI.REC.1397.026. Verbal informed consent was obtained from all subjects/patients in the base study, Iran STEPs 2016 survey. Verbal consent was witnessed and formally recorded.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980021002986.

click here to view supplementary material

References

- 1. Roth GA, Abate D, Abate KH et al. (2018) Global, regional, and national age-sex-specific mortality for 282 causes of death in 195 countries and territories, 1980–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 392, 1736–1788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Yarahmadi S, Etemad K, Hazaveh AM et al. (2013) Urbanization and non-communicable risk factors in the capital city of 6 big provinces of Iran. Iran J Public Health 42, Suppl. 1, 113. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Afshin A, Micha R, Khatibzadeh S et al. (2015) The impact of dietary habits and metabolic risk factors on cardiovascular and diabetes mortality in countries of the Middle East and North Africa in 2010: a comparative risk assessment analysis. BMJ Open 5, e006385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Azadnajafabad S, Mohammadi E, Aminorroaya A et al. (2021) Non-communicable diseases’ risk factors in Iran; a review of the present status and action plans. J Diabetes Metabol Disord, 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fahimi S & Pharoah P (2012) Reducing salt intake in Iran: priorities and challenges. Arch Iran Med 15, 110–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Afshin A, Sur PJ, Fay KA et al. (2019) Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 393, 1958–1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. He FJ & MacGregor GA (2009) A comprehensive review on salt and health and current experience of worldwide salt reduction programmes. J Hum Hypertens 23, 363–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Intersalt Cooperative Research Group (1988) Intersalt: an international study of electrolyte excretion and blood pressure. Results for 24 h urinary sodium and potassium excretion. BMJ 297, 319–328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. He FJ & MacGregor GA (2007) Salt, blood pressure and cardiovascular disease. Curr Opin Cardiol 22, 298–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Malekzadeh R, Derakhshan MH & Malekzadeh Z (2009) Gastric cancer in Iran: epidemiology and risk factors. Arch Iran Med 12, 576–583. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tsugane S (2005) Salt, salted food intake, and risk of gastric cancer: epidemiologic evidence. Cancer Sci 96, 1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mohammadi E, Aminorroaya A, Fattahi N et al. (2020) Epidemiologic pattern of cancers in Iran; current knowledge and future perspective. J Diabetes Metabol Disord 20, 825–829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cappuccio FP, Kalaitzidis R, Duneclift S et al. (2000) Unravelling the links between calcium excretion, salt intake, hypertension, kidney stones and bone metabolism. J Nephrol 13, 169–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Devine A, Criddle RA, Dick IM et al. (1995) A longitudinal study of the effect of sodium and calcium intakes on regional bone density in postmenopausal women. Am J Clin Nutr 62, 740–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Du Cailar G, Ribstein J, Daures J-P et al. (1992) Sodium and left ventricular mass in untreated hypertensive and normotensive subjects. Am J Physiol 263, H177–H181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Perry I & Beevers D (1992) Salt intake and stroke: a possible direct effect. J Hum Hypertens 6, 23–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Verhave JC, Hillege HL, Burgerhof JG et al. (2004) Sodium intake affects urinary albumin excretion especially in overweight subjects. J Intern Med 256, 324–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Burney P (1987) A diet rich in sodium may potentiate asthma: epidemiologic evidence for a new hypothesis. Chest 91, 143S–148S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. He FJ, Markandu ND, Sagnella GA et al. (2001) Effect of salt intake on renal excretion of water in humans. Hypertension 38, 317–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lachat C, Otchere S, Roberfroid D et al. (2013) Diet and physical activity for the prevention of noncommunicable diseases in low-and middle-income countries: a systematic policy review. PLoS Med 10, e1001465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Nugent R, Bertram MY, Jan S et al. (2018) Investing in non-communicable disease prevention and management to advance the Sustainable Development Goals. Lancet 391, 2029–2035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Aminorroaya A, Fattahi N, Azadnajafabad S et al. (2020) Burden of non-communicable diseases in Iran: past, present, and future. J Diabetes Metabol Disord, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Alvaredo F, Assouad L & Piketty T (2019) Measuring inequality in the Middle East 1990–2016: the world’s most unequal region?. Rev Income Wealth 65, 685–711. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ghazizadeh-Hashemi S & Larijani B (2015) National Action Plan for Prevention and Control of Non Communicable Diseases and the Related Risk Factors in the Islamic Republic of Iran, 2015–2025. Tehran, Iran: Aftab e Andisheh Publications. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gholami A, Baradaran HR, Khatibzadeh S et al. (2018) National and subnational cardiovascular diseases mortality attributable to salt consumption in Iran by sex and age from 1990 to 2016. Arch Iran Med 21, 122–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rezaei S, Mahmoudi Z, Sheidaei A et al. (2018) Salt intake among Iranian population: the first national report on salt intake in Iran. J Hypertens 36, 2380–2389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mohammadifard N, Khosravi A, Salas-Salvadó J et al. (2019) Trend of salt intake measured by 24-h urine collection samples among Iranian adults population between 1998 and 2013: the Isfahan salt study. Nutr Metabol Cardiovasc Dis 29, 1323–1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Erdem Y, Akpolat T, Derici Ü et al. (2017) Dietary sources of high sodium intake in Turkey: SALTURK II. Nutrients 9, 933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Erdem Y, Arici M, Altun B et al. (2010) The relationship between hypertension and salt intake in Turkish population: SALTURK study. Blood Press 19, 313–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Musaiger AO (2002) Diet and prevention of coronary heart disease in the Arab Middle East countries. Med Principles Pract 11, Suppl. 2, 9–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Nasreddine L, Akl C, Al-Shaar L et al. (2014) Consumer knowledge, attitudes and salt-related behavior in the Middle-East: the case of Lebanon. Nutrients 6, 5079–5102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mohammadifard N, Fahimi S, Khosravi A et al. (2012) Advocacy strategies and action plans for reducing salt intake in Iran. Arch Iran Med 15, 320–324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Fattahi N, Azadnajafabad S, Mohammadi E et al. (2021) Geographical, gender and age inequalities in non-communicable diseases both at national and provincial levels in Iran. J Diabetes Metabol Disord, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Cappuccio FP, Ji C, Donfrancesco C et al. (2015) Geographic and socioeconomic variation of sodium and potassium intake in Italy: results from the MINISAL-GIRCSI programme. BMJ Open 5, e007467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ji C & Cappuccio FP (2014) Socioeconomic inequality in salt intake in Britain 10 years after a national salt reduction programme. BMJ Open 4, e005683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ji C, Kandala N-B & Cappuccio FP (2013) Spatial variation of salt intake in Britain and association with socioeconomic status. BMJ Open 3, e002246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Powles J, Fahimi S, Micha R et al. (2013) Global, regional and national sodium intakes in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis of 24 h urinary sodium excretion and dietary surveys worldwide. BMJ Open 3, e003733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Mazloomy Mahmoodabad SS, Tehrani H, Gholian-Aval M et al. (2016) The effect of social class on the amount of salt intake in patients with hypertension. Blood Press 25, 360–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Djalalinia S, Modirian M, Sheidaei A et al. (2017) Protocol design for large–scale cross–sectional studies of surveillance of risk factors of non–communicable diseases in Iran: STEPs 2016. Arch Iran Med 20, 608–616. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Peng Y, Li W, Wang Y et al. (2016) Validation and assessment of three methods to estimate 24-h urinary sodium excretion from spot urine samples in Chinese adults. PloS One 11, e0149655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. World Health Organization (2007) Reducing Salt Intake in Populations: Report of a WHO Forum and Technical Meeting, 5–7 October 2006, Paris, France. https://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/Salt_Report_VC_april07.pdf (accessed August 2020).

- 42. Ghosh M & Rao J (1994) Small area estimation: an appraisal. Statist Sci 9, 55–76. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Rao JNK (2017) Small-area estimation. In Wiley StatsRef: Statistics Reference Online, pp. 1–8 [Balakrishnan N, Colton T, Everitt B et al. , editors]. Hoboken, NJ, USA: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Farzadfar F, Danaei G, Namdaritabar H et al. (2011) National and subnational mortality effects of metabolic risk factors and smoking in Iran: a comparative risk assessment. Popul Health Metr 9, 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Vyas S & Kumaranayake L (2006) Constructing socio-economic status indices: how to use principal components analysis. Health Policy Plan 21, 459–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Erreygers G (2009) Correcting the concentration index. J Health Econ 28, 504–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Statistical Centre of Iran (2017) Income and Costs of Iranian Families 2016. Available at https://www.amar.org.ir/ (accessed August 2020).

- 48. Mirzaei M, Soltani M, Namayandeh M et al. (2014) Sodium and potassium intake of urban dwellers: nothing changed in Yazd, Iran. J Health Popul Nutr 32, 111. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Rafiei M, Boshtam M, Sarraf-Zadegan N et al. (2008) The relation between salt intake and blood pressure among Iranians. Kuwait Med J 40, 191–195. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Mazloomi MSS, Motlagh Z, Morowati SMA et al. (2011) The efficacy of reasoned action theory in determining factors related to salt consumption among women referring to Yazd health care centers. Health Syst Res 7, 504–514. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Frye CA & Demolar GL (1994) Menstrual cycle and sex differences influence salt preference. Physiol Behav 55, 193–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Verma P, Mahajan KK, Mittal S et al. (2005) Salt preference across different phases of menstrual cycle. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol 49, 99–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Davy SR, Benes BA & Driskell JA (2006) Sex differences in dieting trends, eating habits, and nutrition beliefs of a group of Midwestern college students. J Am Diet Assoc 106, 1673–1677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Li K-K, Concepcion RY, Lee H et al. (2012) An examination of sex differences in relation to the eating habits and nutrient intakes of university students. J Nutr Educ Behav 44, 246–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Turrell G (1997) Determinants of gender differences in dietary behavior. Nutr Res 17, 1105–1120. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Ghaddar S, Brown CJ, Pagán JA et al. (2010) Acculturation and healthy lifestyle habits among Hispanics in United States-Mexico border communities. Rev Pan Am Salud Publica 28, 190–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Montoya JA, Salinas JJ, Barroso CS et al. (2011) Nativity and nutritional behaviors in the Mexican origin population living in the US-Mexico border region. J Immigr Minor Health 13, 94–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Li Q, Cui Y, Jin R et al. (2017) Enjoyment of spicy flavor enhances central salty-taste perception and reduces salt intake and blood pressure. Hypertension 70, 1291–1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Singh RB, Dubnov G, Niaz MA et al. (2002) Effect of an Indo-Mediterranean diet on progression of coronary artery disease in high risk patients (Indo-Mediterranean diet heart study): a randomised single-blind trial. Lancet 360, 1455–1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Curic D, Novotni D, Skevin D et al. (2008) Design of a quality index for the objective evaluation of bread quality: application to wheat breads using selected bake off technology for bread making. Food Res Int 41, 714–719. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Isaka Y, Moriyama T & Kanda K (2017) The SONG (salt intake and origin from general foods) study-a large-scale survey of the eating habits and dietary salt intake in the working-age population. Intern Med 56, 2423–2430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Kamran A, Azadbakht L, Sharifirad G et al. (2014) Sodium intake, dietary knowledge, and illness perceptions of controlled and uncontrolled rural hypertensive patients. Int J Hypertens 2014, 245480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. World Health Organization (2011) Strategies to Monitor and Evaluate Population Sodium Consumption and Sources of Sodium in the Diet: Report of a Joint Technical Meeting Convened by WHO and the Government of Canada. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/44614 (accessed August 2020).

- 64. Ji C, Miller M, Venezia A et al. (2014) Comparisons of spot v. 24-h urine samples for estimating population salt intake: validation study in two independent samples of adults in Britain and Italy. Nutr Metabol Cardiovasc Dis 24, 140–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Ji C, Sykes L, Paul C et al. (2012) Systematic review of studies comparing 24-h and spot urine collections for estimating population salt intake. Rev Pan Am Salud Pública 32, 307–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Mohammadifard N, Khosravi A, Esmaillzadeh A et al. (2016) Validation of simplified tools for assessment of sodium intake in Iranian population: rationale, design and initial findings. Arch Iran Med 19, 652–658. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Eslamizad S, Kobarfard F, Tsitsimpikou C et al. (2019) Health risk assessment of acrylamide in bread in Iran using LC-MS/MS. Food Chem Toxicol 126, 162–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Aalipour Hafshajani F, Mahdavi Hafshajani F & Aalipour Hafshajani M (2019) Evaluation of salt, sodium, and potassium intake through bread consumption in Chaharmahal and Bakhtiari Province. In J Epidemiol Res 6, 60–64. [Google Scholar]

- 69. Namayandeh SM, Lotfi MH, Jafari V et al. (2018) Salt content in traditional and nontraditional breads in Yazd City, Iran, 2015–2016. J Nutr Food Secur 3, 185–192. [Google Scholar]

- 70. Maghroun M, Sajjadi F, Sarhanghpour M et al. (2015) Salt and sodium content in Iranian breads. Hakim Res J 18, 209–216. [Google Scholar]

- 71. Jafari M, Mohammadi M, Ghazizadeh H et al. (2016) Feasibility and outcome of reducing salt in bread: a community trial in Southern Iran. Glob J Health Sci 8, 163. [Google Scholar]

- 72. Wyness LA, Butriss JL & Stanner SA (2012) Reducing the population’s sodium intake: the UK Food Standards Agency’s salt reduction programme. Public Health Nutr 15, 254–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Hadian Z, Feyzollahi E, Honarvar Z et al. (2020) Assessment of salt (sodium chloride) content in traditional and industrial breads in Tehran-2016. Iran J Nutr Sci Food Technol 14, 113–122. [Google Scholar]

- 74. Zibaeinezhad MJ, Houshangi M, Abtahi F et al. (2010) A study of salt (sodium chloride) content in different bread consumed in Shiraz city in spring/summer 2009. Int Cardiovasc Res J 4, 22–27. [Google Scholar]

- 75. Bolhuis DP, Temme EH, Koeman FT et al. (2011) A salt reduction of 50 % in bread does not decrease bread consumption or increase sodium intake by the choice of sandwich fillings. J Nutr 141, 2249–2255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Quilez J & Salas-Salvado J (2012) Salt in bread in Europe: potential benefits of reduction. Nutr Rev 70, 666–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Quilez J & Salas-Salvado J (2016) The feasibility and acceptability of reducing salt in partially baked bread: a Spanish case study. Public Health Nutr 19, 983–987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Dagdelen AF & Gocmen D (2007) Effects of glucose oxidase, hemicellulase and ascorbic acid on dough and bread quality. J Food Qual 30, 1009–1022. [Google Scholar]

- 79. Sheikholeslami Z, Karimi M, Komeili HR et al. (2018) A new mixed bread formula with improved physicochemical properties by using hull-less barley flour at the presence of guar gum and ascorbic acid. LWT 93, 628–633. [Google Scholar]

- 80. World Health Organization (2013) Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases 2013–2020. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241506236 (accessed August 2020).

- 81. World Health Organization (2016) The SHAKE Technical Package for Salt Reduction. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/250135/9789241511346-eng.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed August 2020).

- 82. He FJ, Jenner KH & Macgregor GA (2010) WASH-world action on salt and health. Kidney Int 78, 745–753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. He FJ, Wu Y, Feng X-X et al. (2015) School based education programme to reduce salt intake in children and their families (School-EduSalt): cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ 350, h770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Ma Y, Feng X, Ma J et al. (2019) Social support, social network and salt-reduction behaviours in children: a substudy of the School-EduSalt trial. BMJ Open 9, e028126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. McLaren L, Sumar N, Barberio AM et al. (2016) Population-level interventions in government jurisdictions for dietary sodium reduction. Cochrane Database Syst Rev issue 9, CD010166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 86. Santos JA, Trieu K, Raj TS et al. (2017) The science of salt: a regularly updated systematic review of the implementation of salt reduction interventions (March–August 2016). J Clin Hypertens 19, 439–451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Khosravi A, Kelishadi R, Sarrafzadegan N et al. (2012) Impact of a community-based lifestyle intervention program on blood pressure and salt intake of normotensive adult population in a developing country. J Res Med Sci 17, 235. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Azadnajafabad S, Saeedi Moghaddam S, Mohammadi E et al. (2021) Importance of population-wide studies in controlling non-communicable diseases: achievements of non-communicable diseases research center, endocrinology and metabolism research institute. Iran J Diabetes Lipid Disord 20, 25–33. [Google Scholar]

- 89. Talaei M, Mohammadifard N, Khaje M-R et al. (2013) Healthy bread initiative: methods, findings, and theories—Isfahan Healthy Heart Program. J Health Popul Nutr 31, 49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Zargaraan A, Dinarvand R & Hosseini H (2017) Nutritional traffic light labeling and taxation on unhealthy food products in Iran: health policies to prevent non-communicable diseases. Iran Red Crescent Med J 19, 18. [Google Scholar]

- 91. Mahdavi AM, Abdolahi P & Mahdavi R (2012) Knowledge, attitude and practice between medical and non-medical sciences students about food labeling. Health Promot Perspect 2, 173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Esfandiari Z, Marasi MR, Estaki F et al. (2019) Influence of education on knowledge, attitude and practices of students of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences to traffic light inserted on food labeling. Tehran Univ Med J 77, 54–62. [Google Scholar]

- 93. Esfandiari Z, Mirlohi M, Tanha JM et al. (2020) Effect of face-to-face education on knowledge, attitudes, and practices toward “traffic light” food labeling in Isfahan society, Iran. Int Q Community Health Educ 41, 275–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Bazhan M, Mirghotbi M & Amiri Z (2015) Food labels: an analysis of the consumers’ reasons for non-use. Arch Adv Biosci 6, 2–10. [Google Scholar]

- 95. Edalati S, Omidvar N, Haghighian Roudsari A et al. (2020) Development and implementation of nutrition labelling in Iran: a retrospective policy analysis. Int J Health Plann Manag 35, e28–e44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Gillespie DO, Allen K, Guzman-Castillo M et al. (2015) The health equity and effectiveness of policy options to reduce dietary salt intake in England: policy forecast. PloS One 10, e0127927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Appel LJ, Angell SY, Cobb LK et al. (2012) Population-wide sodium reduction: the bumpy road from evidence to policy. Ann Epidemiol 22, 417–425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980021002986.

click here to view supplementary material