Abstract

Objective:

To examine the literature and identify main themes, methods and results of studies concerning food and nutrition addressed in research on transgender populations.

Design:

A systematic review conducted through July 2020 in the MedLine/PubMed, Scopus and Web of Science databases.

Results:

Of the 778 studies identified in the databases, we selected thirty-seven. The studies were recent, most of them published after 2015, being produced in Global North countries. The most often used study design was cross-sectional; the least frequently used study design was ethnographic. Body image and weight control were predominant themes (n 25), followed by food and nutrition security (n 5), nutritional status (n 5), nutritional health assistance (n 1) and emic visions of healthy eating (n 1).

Conclusions:

The transgender community presents body, food and nutritional relationships traversed by its unique gender experience, which challenges dietary and nutritional recommendations based on the traditional division by sex (male and female). We need to complete the lacking research and understand contexts in the Global South, strategically investing in exploratory-ethnographic research, to develop categories of analysis and recommendations that consider the transgender experience.

Keywords: Nutritional care, Gender identity, Gender nonconforming, Sexual and gender minority

It is estimated that the global prevalence of transgender and gender nonconforming people is 4·6 per 100 000 individuals, or 1 in every 21 739 individuals, with a significant increase in the last 50 years(1). Some transgender people seek to express their gender identity(2) by realising a gender transition (Fig. 1), a process that can involve everything from changing clothes, names and pronouns to health needs, such as hormone replacement therapy (HRT) and/or gender affirming surgeries (GAS), which include surgical interventions such as vaginoplasty, mastectomy, phalloplasty and hysterectomy among others(3). Such interventions are sought by about 80% of the transgender population and are directly related to well-being(4).

Fig. 1.

Gender classification in cisgender and transgender, accordingly continuity or discontinuity concerning sex and gender identity. We use the term cisgender to describe a person to whom the gender identity matches with the sex assigned at birth, and transgender to a person to whom that correspondence does not exist. The sex assigned at birth corresponds to biological features, that is, sexual organs, reproductive structures and hormones. However, bodies encompass broader social and cultural meanings, such as techniques, rules about how to be ‘man’ or ‘woman’, behaviours, costumes and preferences. We name gender identity the way people perceive their selves in this socio-cultural system. This concept is not limited to masculine or feminine characteristics but to several possibilities that mix different characteristic of genders or none of them(2,3)

Transgender people suffer many forms of stigma throughout their lives. The Gender Minority Stress Theory proposes that the stigma attached to gender identity adversely affects health: in the short term, with the body’s response to stress and elevation of cortisol levels, but also chronically by contributing to the development of non-transmissible chronic diseases, communicable diseases and mental health problems(5). Stigma against transgender people is expressed in various ways, including social exclusion by family and friends; physical and mental violence from both relatives and strangers; and through the institutional creation of barriers to access in education, health, work and social services, thus affecting all aspects of social life(6).

Most gender studies in the fields of food and nutrition emphasise sexual and reproductive differences, accounting for only the binary conception of man and woman. Yet gender relations are involved in the development of obesity(7), in determining food insecurity(8) and in eating behaviours(9), among others. Consolidated surveys provide a basis for anthropometric and food consumption parameters and present specific recommendations based on gender. However, though important for orienting populations around the world, such recommendations do not address individuals who are transgender(10). To promote gender-based nutritional and food care, we need to know what nutritional and food research informs us about transgender communities.

In this paper, our general premise is that the experience of transgender individuals affects their food and nutritional demands differently than cisgender people, and therefore, needs to be included in recommendations, guidelines, and food and nutrition policies. We highlight the two principal issues that are responsible for mobilising our hypothesis: stigma and gender transition. The stigma experienced by the transgender community impacts body and body image relationships, being associated with food intake capacity, higher cardio-metabolic risk, diabetes and mental health problems such as anxiety, depression and suicide(6). HRT is thus a healthcare need that is also used as a strategy to alleviate social suffering. HRT confers changes in body composition, principally through redistribution of fat and muscle mass, which may be similar or not to the intended gender, since the desired gender is not necessarily the opposite of the sex attributed to birth(4). To discover the repercussions of these dimensions and others on transgender food and nutritional demands, we see the need to gather more evidence.

Our aim with this review is to gather and organise transgender population studies in the fields of food and nutrition. We set this goal by considering that research on food and nutrition for transgender people is fragmented and needs to be connected to provide the state of evidence we have available up to date about this topic. We sought to systematise and characterise the knowledge thus far produced so that future research may be performed to fill the identified gaps. We guided our review based on the following question: What are the geographic coverage, themes, and methodological and principal approaches in food and nutrition research that address the transgender population? As geographic coverage, we considered the period in which the surveys were performed and the countries of origin of both the researchers and participants. As themes, we considered the general areas in which the study might be linked to the objective. As methodological approaches, we considered study designs and techniques; finally, we identified the main results, conclusions and contributions related to the transgender population and food and nutrition.

Methods

This review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses recommendations. We did not register our protocol for this review because our research does not directly analyse health-related results.

Search strategy

We conducted the search between the months of June and July of 2020. The search strategies were developed based on consultations with specialists in the field, as well as a previous comprehensive food and nutrition studies review(11). To cover as many terms as possible related to the transgender population, we used the most frequent words, extracted from a systematic review of LGBTQ theme reviews(12).

The terms: (FOOD OR DIET OR NUTRITION OR EATING) and (TRANSSEXUAL OR TRANSSEXUAL OR TRANSGENDER OR TRANSVESTITE OR TRANS-SEXUALITY OR ‘GENDER DYSPHORIA’). We conducted searches in the Scopus, MedLine/PubMed (via the National Library of Medicine) and Web of Science databases, all of which revealed excellent performance in gathering evidence for systematic reviews(13) (see online supplementary material, Supplemental Table S1).

Study selection

The titles and abstracts were read by two independent authors (S.M.G. and M.F.A.M.), and in case of disagreement, a third author was consulted (M.C.M.J.). We relied on the assistance of Mendeley and Rayyan Qatar Computing Research Institute (QCRI) reference managers to combine the databases, exclude duplicates, read titles and abstracts, and select and analyse disagreements.

Studies conducted in the field of human and dietary nutrition were included, without limitation as to year, language or study design. Studies with a specific focus on hormonal treatment, literature reviews, theoretical essays, abstracts, dissertations, theses, books or articles whose titles that were not available for reading in the referenced journal were excluded.

The complete texts were retrieved and revised by S.M.G. to confirm the study’s eligibility, and in case of doubts the other authors were consulted. A supplementary manual search was performed to identify additional studies using the references found in the selected articles.

Quality assessment

We used the following recommendations for assessing methodological quality: qualitative studies were evaluated using the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ)(14); cross-sectional observational studies were evaluated using the Joanna Briggs Institute Prevalence Studies Checklist(15). Cohort and case–control studies were assessed using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale(16). The observational studies were also evaluated using the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) statement(17). Case reports were evaluated using the Methodological Quality and Synthesis of Case Series and Case Reports(18).

Studies were classified as high quality, moderate quality or low quality, using the Jacob, Araújo and Albuquerque criteria(19). Studies were classified as high quality when fulfilling > 80% of the criteria on the referred checklist, as moderate quality when fulfilling from 79 to 50% of the criteria and as low quality when fulfilling < 50% of the required criteria. In cases where two instruments were used and the classifications were divergent, the lower classification was considered.

Data extraction

The data were extracted by S.M.G. and verified by M.F.A.M. and M.C.M.J. We extracted the following information from the studies: author(s), country of correspondence, author, year, setting, study design, study aim, participants, data collection techniques and significant results. We obtained the Human Development Index of the corresponding authors’ countries in the 2019 Human Development Index – Ranking(20).

Summary of results

We have presented the results in a descriptive manner and using absolute frequency. We have produced summaries of each of the articles and systematised the principal conclusions. The articles were subsequently grouped according to their principal themes.

Results

Studies selection

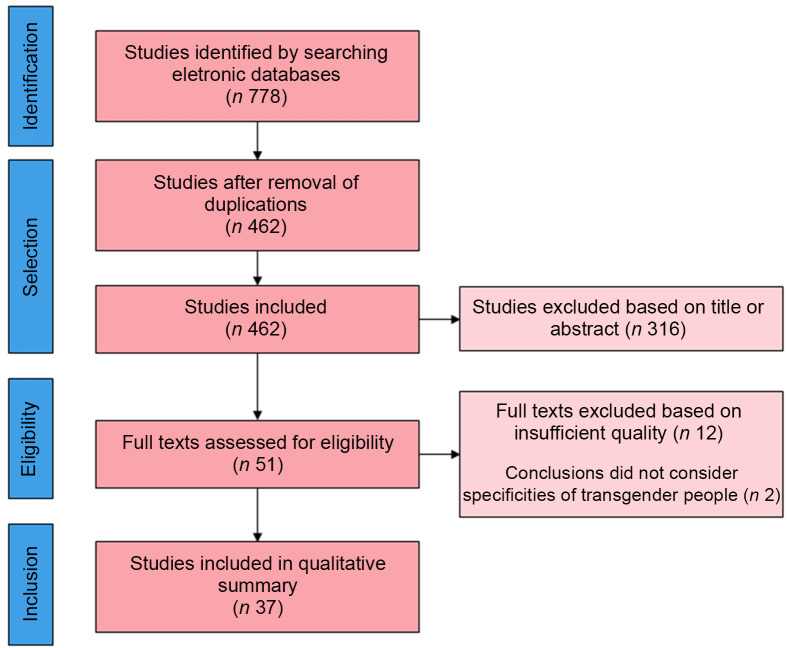

The process of identifying and selecting articles is described in Fig. 2. We identified 778 studies in the databases, 221 in MedLine/PubMed, 261 in Scopus and 296 in Web of Science. After excluding duplicate studies, 462 were maintained. We performed a thorough reading of the titles and abstracts and excluded theoretical studies, abstracts, non-peer-reviewed and out of scope articles. Of the total studies, fifty-one studies were read in full and assessed for quality; of these, thirty-seven articles were satisfactory and thus included. The selected articles are characterised in Table 1.

Fig. 2.

Flow diagram of studies included in the present review on transgender peoples and food and nutrition research

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies about transgender and gender nonconforming peoples’ consideration in food and nutrition research

| n | Author(s), year | Setting | Study design | Study aim | Participants | Data collection techniques | Important results | Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Algars, Santtila and Sandnabba, 2010 | The population-based study, Finland | Case–control/quantitative | Understand the relationship between gender identity, body image and eating disorders in a population-based sample | 349 transgender woman and 222 transgender men, mean age of 25 years old, with respective control paired for age and sex assigned at birth | Surveys | Participants with gender identity conflicts had high levels of body dissatisfaction and eating disorders, compared with control | Strong |

| 2 | Algars et al., 2012 | The population-based study, Finland | Case study/qualitative | Examine eating behaviours and cognitions in a sample of transgender Finnish adults | 20 transgender men and transgender woman, age between 21 and 62 years old | Semi-structured interviews | Participants developed eating disorders currently or previously to suppress the body characteristic of sex assigned to birth. Gender transition relieved symptoms of eating disorders | Moderate |

| 3 | Auer et al., 2016 | Ghent University Hospital, Ghent, Belgium | Cohort/quantitative | Analyse the metabolic profile of transgender peoples before and after hormonal treatment | 20 men and women transgender people, with more than 18 years old, matched for sex and age | Anthropometrics and laboratory measures and targeted metabolomics | In transwoman: the hormonal therapy reduced the muscle mass and increases relative fat In transmen: the hormonal therapy increases muscle mass The metabolic did not change in the groups, except for the citrulline–arginine ratio, amino acid lysine, alanine and asymmetric dimethylarginine |

Moderate |

| 4 | Avila, Golden and Aye, 2019 | Gender multidisciplinary academic clinic, does not specify city or country | Cross-sectional/quantitative | Assess the frequency of intentional weight manipulation behaviours for the purpose of gender assertion | 107 transgender peoples between 13 and 22 years old | Surveys | The prevalence of weight manipulation for gender assertion was 63% | Strong |

| 5 | Bandini et al., 2013 | Gender identity and eating behaviour clinics in the cities of Florence and Bologna, Italy | Case–control/quantitative | Assess similarities and differences in body image and general psychopathology between transgender people, cisgender people with eating disorders and a control group | 100 transgender people, 94 cisgender people with an eating disorder and 107 cisgender subjects without an eating disorder, all adults | Surveys and anthropometric measures | Transgender people and people with eating disorders are characterised by severe bodily restlessness. In transgender individuals, body disquiet varies by stage of gender change and by biological sex, while in cisgender individuals with eating disorders, it is related to general psychopathology | Strong |

| 6 | Beaty, Trees and Mehler, 2017 | Denver, USA | Case report | Describe a case of recurrent hypophosphatemia in a transgender woman with anorexia nervosa | A 27-year-old transgender woman with a history of restrictive anorexia nervosa | Anthropometrics and laboratory measures and physical examination | Hospital and residential treatment lasted 13 weeks. Levels of Ca in the diet were considered sufficient in the second week of hospitalisation and vitamin D in the fourth week. The patient was discharged and had normal P levels in the subsequent 3 weeks | Moderate |

| 7 | Bell, Rieger and Hirsch, 2019 | The population-based study, Johnson, USA | Cross-sectional/quantitative | Compare the percentage of eating disorder symptoms, psychological symptoms, and risk and protective factors between gay and lesbian cis-gendered people and transgender people | 320 individuals identified as gay, lesbian and transgender people, with an average age of 38·26 years | Surveys | Transgender people had a higher prevalence of dissatisfaction with eating patterns than gay and lesbian | Moderate |

| 8 | Brewster et al., 2019 | Community-based sample, USA | Cross-sectional/quantitative | Understanding body image problems and symptomatology of eating disorders in transgender women | 205 transgender women, between 16 and 68 years old | Web-based survey | Sexual objectification, internalisation of socio-cultural patterns of attractiveness, body surveillance, body dissatisfaction and discrimination are direct or indirect predictors of eating disorders | Moderate |

| 9 | Bishop et al., 2020 | The population-based study, Minnesota, USA | Cross-sectional/quantitative | Examine eating behaviours, physical activity, weight-related bullying among groups of transgender and cisgender people | 80 794 transgender and cisgender students, from the 9th and 11th grades | Surveys | Transgender students were more likely to feed on the free or reduced-price supply and fast foods and soft drinks, and less frequently to eat fruit and milk. Transgender students were also more likely to develop obesity, weight bullying and less physical activity | Strong |

| 10 | Diemer et al., 2015 | National colleges and universities, USA | Cross-sectional/quantitative | Examine the association between gender identity and sexual orientation and the occurrence of eating disorders, compensatory behaviours in cis and transgender students | 289 024 participants, including cisgender and transgender people, with diverse sexual orientation and an average age of 20 years | Web-based survey and sampled in-person | The prevalence of eating disorders, use of diet pills and stimulation of vomiting or use of laxatives were higher in transgender people, especially among those who were unsure of their sexual orientation | Moderate |

| 11 | Diemer et al., 2018 | Community-based sample, Massachusetts, USA | Cross-sectional/quantitative | Investigate the prevalence of eating disorders in a sample with diverse gender identity | 452 transgender and gender-nonconforming people, aged 18–75 years | Web-based survey and sampled in-person | The prevalence of diagnosed eating disorders was 4·7%. Individuals with non-binary gender identities were more likely to be diagnosed with an eating disorder than people with binary gender identities | Strong |

| 12 | Duffy, Henkel, and Earnshaw, 2016 | Community-based sample, USA, Europe and Canada | Cross-sectional/qualitative | Examine assistance experiences during the treatment of transgender people with eating disorders | 84 transgender and gender-diverse, 18–33 years old | Web-based questionnaire | 56% of participants reported that their eating disorders were not related to their physical bodies. Most treatment experiences were marked by inappropriate and disrespectful approaches to gender identities | Moderate |

| 13 | Gordon et al., 2016 | Community-based sample, Boston metropolitan area, USA | Cross-sectional/qualitative | Explore body control behaviours in an ethnically diverse sample of transgender women | 21 ethnically diverse young transgender women, aged 18–32 years | Semi-structured interviews | Compulsive eating was the most frequent form of body control. The development of eating disorders was related to the ideal notions of femininity, racial/ethnic patterns, the need to reaffirm gender, the stigma suffered, the use of hormones, and the support and resilience networks presented | Moderate |

| 14 | Guss et al., 2016 | Public high-school, Massachusetts, USA | Cross-sectional/quantitative | Examine differences in disordered weight control behaviours, non-prescribed steroids and perceived weight status among transgender and cisgender students | 2473 transgender and cisgender students in grades 9–12 | Surveys | Transgender students were more likely to fast for more than 24 h, use diet pills, take laxatives, use steroids without a prescription and have symptoms of an image disorder | Strong |

| 15 | Henderson et al., 2019 | Population-based sample, Virgínia, Ohio, Delaware, Georgia, Kansas, Minnesota and Missouri, USA | Cross-sectional/quantitative | Examine the association between gender identity and stress related to food and housing | 261 transgender and 52 799 cisgender person adults aged 18 years or older | Surveys | Transgender people had lower-income and more significant stress related to food | Strong |

| 16 | Himmelstein, Puhl and Watson, 2019 | National population-based sample, USA | Cross-sectional/quantitative | Examine the relationship between weight-based victimisation and eating disorders, diet and health | 9838 participants of different sexual and gender identities, aged between 13 and 17 years old | Web-based surveys | Transgender, cisgender and non-binary adolescents presented diets and strategies for weight control, binge eating, little physical activity, difficulties falling asleep and dealing with food stress | Strong |

| 17 | Hiraide et al., 2017 | Japan, does not specify the city | Case report | To present the longitudinal course of two Japanese transgender patients with eating disorders undergoing gender transition | A woman and a transgender man, both 35 years old | Hospital records and clinical monitoring | Gender reassignment processes reduced body dissatisfaction and improved patients’ symptoms of eating disorders | Moderate |

| 18 | Jones et al., 2018 | Community-based sample, national transgender health service, UK | Cross-sectional/quantitative | Explore the risk factors for eating disorder symptoms in transgender people and the role of hormones | 563 transgender people, with an average age of 29·49 years | Surveys | Eating disorder symptoms were more prevalent in the transgender population who were not on hormone treatment | Strong |

| 19 | Khoosal et al., 2014 | Community-based sample, The Leicester Gender Identity Clinic, UK | Cohort/quantitative | Examine eating disorders in transgender women before and after gender reassignment surgery, compared with cisgender controls | 40 transgender women, with an average age of 41·8 years and 147 cisgender women diagnosed with an eating disorder with an average age of 27 years | Surveys | After sex change surgery, there was a reduction in body dissatisfaction among transgender women. In comparison with controls, only body perfectionism was superior in transgender women | Moderate |

| 20 | Kirby and Linde, 2020 | Community-based sample, Midwestern University, Illinois, USA | Cross-sectional/qualitative | Know the health disparities related to nutrition and the barriers to adequate food and health by transgender and gender nonconforming university students | 26 transgender university students, with an average age of 22·7 years | Questionnaires and semi-structured interviews | The students had a large consumption of processed and ultra-processed foods and a high prevalence of food insecurity due to access, cost, preparation, health status and expiration date. The trend toward seating disorders was also an emerging topic | Moderate |

| 21 | Linsenmeyer and Rahman, 2018 | USA | Case report | Describe the impact of nutritional interventions on the health of a transgender patient | One transgender man with 27 years old | Questionnaires, biochemical and anthropometric data | The dietary intervention carried out for 1 year has positively impacted daily energy consumption, serum lipid levels, eating disorders and body image trends | Moderate |

| 22 | Linsenmeyer, Drallmeier and Thomure, 2020 | Community-based sample, USA | Case report | Describe the nutritional and food parameters of adult transgender men | 10 transgender men adults | Questionnaires, anthropometric assessment and dietary records | The prevalence of obesity was 65·9%, associated with a low intake of fruits and vegetables and a high Na intake | Moderate |

| 23 | Milington et al., 2020 | Community-based sample, USA | Cross-sectional/quantitative | Compare psychological, laboratory and anthropometric characteristics of a group of adolescents before using puberty blockers and gender hormone treatment concerning the features of the general population | 374 transgender children and adolescents, 78 using blockers, with an average age of 11 years and 296 using hormones for gender transition, with an average age of 16 | Anthropometric, physiological and laboratory data were collected as part of routine medical care | Before starting the treatment of gender affirmation, young transgender people are physiologically similar to the general population of children and adolescents in the USA, except for HDL, which was lower | Strong |

| 24 | Nagata et al., 2020 | Community-based sample, USA | Cross-sectional/quantitative | To evaluate disordered eating attitudes and behaviours in transgender men and women | 484 transgender people, 312 men with an average age of 30·5 years and 172 women with an average age of 41·2 years | Web-based survey | The prevalence of reported eating disorders was 10·6% in transgender men and 8·1% in transgender women. The prevalence of food restriction was 25% in trans men and 30% in trans women | Moderate |

| 25 | Peterson et al., 2020 | Clinical-based sample, Midwestern region, USA | Cross-sectional/quantitative | To explore the performance of the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q) in a sample of young transgender people seeking hormone therapy for gender assertion | 249 transgender people, 11–24 years old | Surveys | The best performance of the questionnaire was revealed when applied in general, without considering subscales. The performance of the questionnaire is similar to that observed in previously published samples of cisgender women | Moderate |

| 26 | Pistella et al., 2020 | Population-based sample in California schools | Cross-sectional/quantitative | Examine gender identity disparities in different types of behaviours related to weight and its relationship with school security in a sample of transgender and cisgender students | 358 transgender and 31 251 non-transgender adolescents, enrolled between grades 6 and 12 | Surveys | In general, transgender students feel less secure at school, but they exhibit healthier eating behaviours when they consider it safe | Strong |

| 27 | Ristori et al., 2019 | Florence, Italy | Case report | Describe clinical cases of transgender adolescents who presented pathological eating behaviours | Two transgender teenagers with an average age of 15 years | Questionnaires and clinical data | After hormonal treatment, the pathological eating behaviours were decreased, and healthy eating habits were restored | Moderate |

| 28 | Russomano, Patterson and Jabson, 2019 | Community-based sample, Southeast USA | Cross-sectional/qualitative | Explore the experiences of food insecurity experienced by transgender people | 20 transgender people were living in food insecurity, between 18 and 50 years old | Telephone interview | The difficulty in finding and maintaining jobs was the main factor in food insecurity and discomfort when seeking food assistance due to discrimination, whether from the government, philanthropy or family networks. The physical and mental health of the participants was affected | Strong |

| 29 | Russomano and Tree., 2020 | Community-based sample, Southeast USA | Cross-sectional/quantitative | Assess the prevalence of food security, access to food policies and the association with perceived levels of stress and resilience | 105 transgender people, mostly between 18 and 34 years old | Web-based surveys | The prevalence of food insecurity was 79%. Only 22% of participants reported using a local food assistance programme. There was no association between stress and resilience and food security | Moderate |

| 30 | Schier and Linsenmeyer, 2019 | NA | Ethnography/qualitative | Describe the food and nutrition messages shared among the transgender community using video blogs | 30 public vlogs of transgender users | Ethnography in online video platform | The messages shared through vlogs concern especially the topics of diet and exercise functions, diet and exercise philosophies, such as making vlogs, advice for success, use of dietary supplements and the effects of hormone therapy | Strong |

| 31 | Simone et al., 2020 | Population-based sample in Minnesota colleges and universities | Cross-sectional/quantitative | Compare self-reported levels of anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa and eating pathology-specific academic impairment (EAI) | 238 transgender and genderqueer students and 13 346 cisgender students | Surveys | Cisgender women and transgender people have higher levels of anorexia, bulimia and eating pathology-specific academic impairment | Strong |

| 32 | Testa, Rider, Haug and Balsam, 2017 | Community-based sample, USA and Canada | Cross-sectional/quantitative | Examine the relationship between gender readjustment surgeries and eating disorders in transgender men and women | 442 transgender people, with an average age of 32·49 years | Web-based surveys | For transgender individuals who expressed a desire for bodily changes, their achievement was indirectly associated with lower levels of eating disorders, mediated by the relationship between non-affirmation of gender and better body satisfaction levels | Strong |

| 33 | Turan et al., 2018 | Istanbul University Cerrahpaşa Medical Faculty, Istanbul, Turkey |

Cohort/quantitative | To investigate the short-term impact of hormone administration on body composition, dietary attitudes and psychopathologies in transgender men | 37 transgender men and 40 cisgender women | Clinical data form | After the 24th week of hormone administration, the participants’ average body weight and BMI increased, body restlessness and general psychopathological symptoms decreased, but eating attitudes and behaviours did not change | Moderate |

| 34 | Vilas et al., 2014 | Community-based sample, Unidade de Distúrbios de Gênero do Hospital Ramón y Cajal, Madrid | Cohort/quantitative | To verify nutritional status, eating behaviour, and lifestyle and its effects on the prevalence of overweight and obesity in transgender people before and after hormonal treatment | 157 transgender individuals, with an average age of 32·9 years | Surveys | 24·24% of transgender men and 10·99% of transgender women were overweight after treatment, 10·61 and 5·49% were obese. The diet was characterised by a high consumption of fats, mainly saturated and cholesterol | Moderate |

| 35 | Vocks, Stahn, Loenser and Legenbauer, 2009 | Population-based sample, Germany, Austria and Switzerland | Case–control/quantitative | Check for differences in weight control, eating disorders and image disorders between transgender and cisgender people | 356 participants, of which 88 transgender women, with an average age of 37·27 years and 43 transgender men, with an average age of 34·95 years | Web-based surveys and questionnaires in a paper-and-pencil version | Transgender women had higher levels of food restriction, concern about food, weight and shape, desire for thinness, bulimia and body dissatisfaction compared with male cisgender controls | Moderate |

| 36 | Watson, Veale and Saewyc, 2017 | Community-based sample, Canada | Cross-sectional/quantitative | Explore the relationship between disordered eating and risk and protection factors for trans youth | 923 transgender people, between 14 and 25 years old | Web-based surveys | The enacted stigma (harassment and discrimination) was associated with greater chances of reported binge eating. Support networks, such as family, school or friends, were associated with lower options of disordered eating. Higher levels of stigma and the absence of a protective factor were highly likely to develop an eating disorder | Moderate |

| 37 | Witcomb et al., 2015 | Population-based sample, USA | Case–control/quantitative | Assess the risk of eating disorders in transgender and cisgender people | 600 participants, with an average age of 35·14 years, of which 200 were transgender | Surveys | Transgender participants had higher levels of risk for eating disorders than their controls. Body dissatisfaction in transgender men was comparable to the group of cisgender men with eating disorders | Moderate |

Study themes and characteristics

The inclusion of gender identity in food and nutrition studies is recent. The first study included in the review was published in 2009(21) and the vast majority of such studies were published since 2015(10,22–51). Of the thirty-seven studies, five concerned food and nutritional security(25,29,37,38,48), twenty-five concerned body image and weight control(21,23,24,26–28,32–34,36,40–47,49,50,52–55), five concerned nutritional status(10,22,30,31,56), one concerned nutritional health care(51) and one involved emic views of healthy eating(39). The most frequent study designs were cross-sectional (n 22), followed by case reports (n 5), case–controls (n 4), cohort studies (n 4) and one ethnographic study (n 1) (see Table 1).

Quality analysis

Of the articles, thirty-seven were judged to be of good or moderate quality and fourteen were classified as low quality, and thus excluded. The lower-quality studies were mostly case reports lacking accurate information concerning either diagnosis, measurement of variables or results. Though some of the selected articles presented a limited sample number, or did not clearly present the sample or selection criteria, we did not consider the limitations discovered as detracting from the merit of our review, since we had excluded those whose failings might compromise their conclusions.

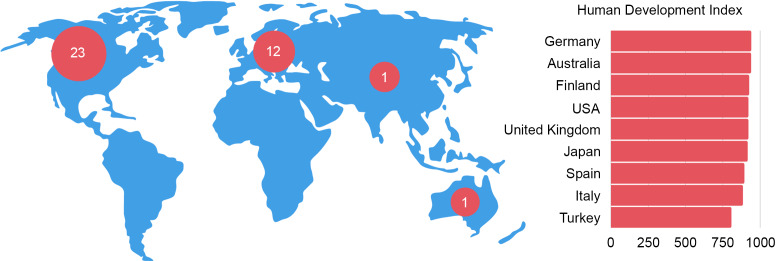

Geographic coverage

The production of knowledge concerning food and nutrition for transgender people is concentrated in the Global North. Most of the principal authors of the studies were linked to institutions in North America and Europe, and in countries with a high Human Development Index (above 0·800), as shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

The landscape of food and nutrition research about transgender people. Map of continents indicated where the main authors of the articles are from, and the Human Development Index of their respective countries

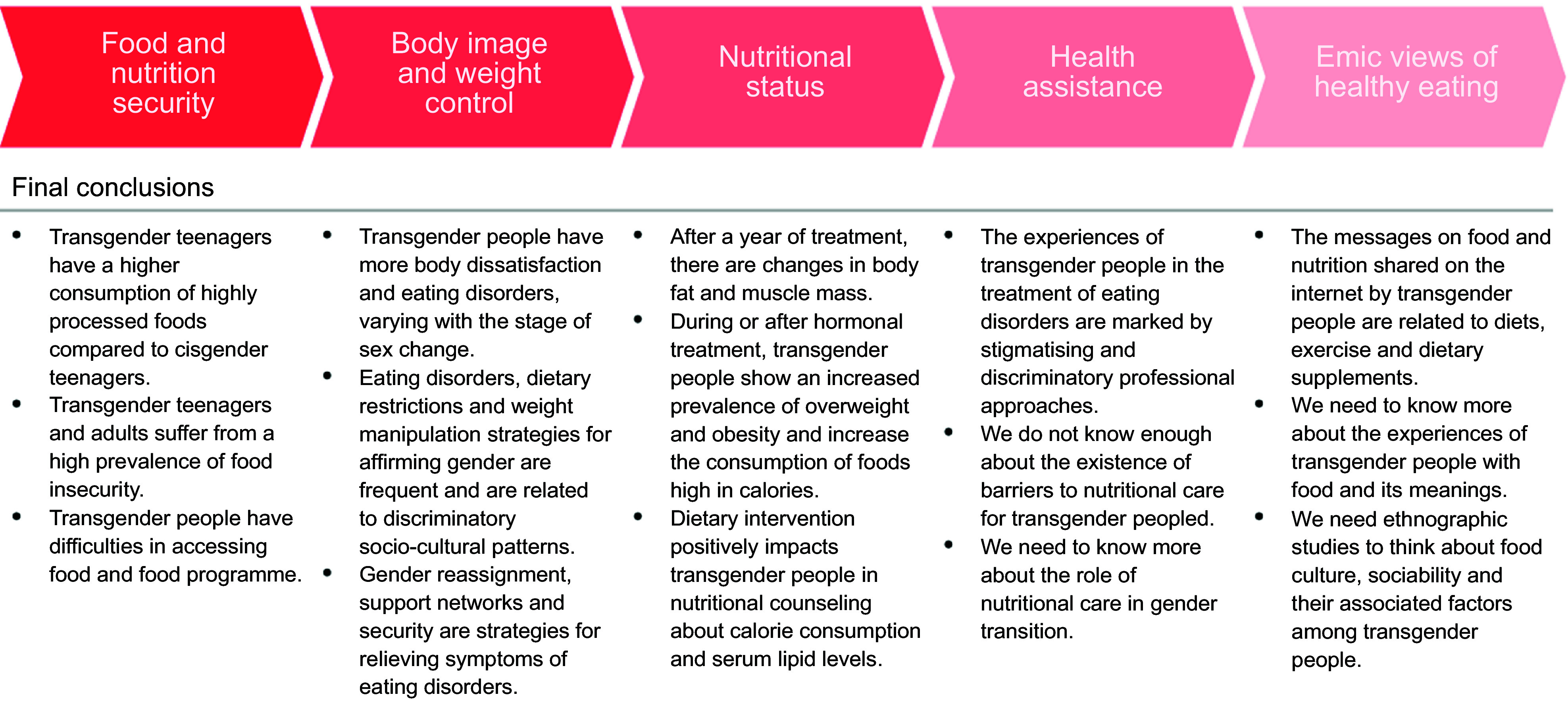

Principal contributions to the fields of food and nutrition

We have summarised the principal conclusions of the articles according to their themes in Fig. 4. Despite the limited number of studies in this review, the prevalence of food insecurity draws one’s attention. In general, transgender people, both adolescents and adults, suffer difficulties in access to food(25,37) and access to food assistance(37) and often consume ultra-processed foods(48). All the food security studies took place in the USA, and factors associated with food insecurity involve the country’s social context, in which food assistance is largely provided by private groups within society, especially religious groups. In these cases, the principal condition that promotes removal of transgender people from food assistance programmes is stigma(37). Due to their low cost, consumption of ultra-processed foods is an alternative for high-school adolescents(48).

Fig. 4.

Broad topics of current food and nutrition research about transgender people with a summary of the main conclusions in the articles reviewed

Food is often used as a strategy for seeking comfort, and this can give rise to problematic relationships to food consumption. A link between body dissatisfaction and eating disorder diagnoses, such as anorexia and bulimia, has been demonstrated by several authors(26,47,49,50,52,55). Food restriction, even when not diagnosed, is most frequently used as an instrument to fit into body and gender standards(21,32). In general, it is difficult to access treatment for eating disorder services that do not discriminate against transgender people(51), leading many in the community to the internet for tips and information on diets, exercises and dietary supplements(39).

For being effective in alleviating social suffering, the process of gender transition through multi-professional assistance is much needed by many transgender people. The effects of gender transition have been demonstrated not only to reduce eating disorders(41) but also to increase the prevalence of overweight and obesity, as well as the increased consumption of energetic foods(56), which makes nutritional therapy necessary. Yet, there are no nutritional recommendations that are appropriate to the context of the transgender population(30). This is true even though certain alternatives are indeed presented during nutritional therapy, such as male and female-based reference values for the related stage of the individual’s hormonal transition (i.e., hormonal composition), and the references for the desired gender(10).

Discussion

Food and nutrition issues are affected by gender in the transgender and gender nonconforming gender communities. Gender studies in the fields of food and nutrition are still recent and leave us with more questions than answers, revealing the need for further studies. In general, food is a means of minimising social suffering in transgender communities. However, in certain contexts, the stigma experienced can deepen food scarcity situations, by contributing to the already high prevalence of food insecurity, diets based on ultra-processed foods and difficulties in accessing adequate nutritional assistance networks.

Below we highlight the principal lessons learned from the systematisation in this review, as well as the need for further exploration of the experiences of food and gender in the Global South, since conclusions for the Global North alone present limited generalisation. Finally, we seek to point out ways to advance nutritional care for the transgender population in the future.

Trends in studies on gender, food and nutrition

Studies on food and nutrition for transgender people, although few, should serve as a guide for future research on the subject. We highlight three principal trends we identified: (1) the binary division of genders between male and female in dietary and nutritional recommendations is insufficient for transgender care; (2) many studies have limited conceptions about the transgender communities and (3) the stage of a gender transition can interfere with food and nutritional outcomes.

First, the contemporary public health demands challenge classic nutritional assessment methods and dietary recommendations to include the transgender population. Studies concerning recommendations for anthropometric measures and Dietary Reference Intake consider a binary division of the sexes (male and female)(10). However, the studies we gathered demonstrate the effects of HRT and GAS on lipid profile, body composition, eating disorder development and behaviour in the transgender population and the need to consider such processes in their health assessments. Therefore, the global prevalence of people who do not conform to the sex attributed at birth increases and suggests the need to update protocols and current recommendations.

Second, the studies we reviewed use different criteria when considering transgender people. The majority of the research focuses on the medical diagnosis of gender dysphoria and the psychopathological relations with food. Researchers must consider the relationship between transgender communities and food cultures beyond a pathological relationship, considering specific ethical assumptions, such as acting in collaboration with the community, using stigma-free language, emphasising participant data protection and avoiding hypotheses that consider conversion, reorientation or restorative therapy(57). Gender dysphoria is not the best criterion for classifying transgender people; Putckett et al. (58) suggest a two-step method for confirming gender in broad population surveys, considering the transgender population as that in which sex and gender do not match.

Finally, we also observed that the existing heterogeneity in the identities and needs of the transgender population makes it necessary to consider characteristics of the population in the development of each research question. As an example, studies related to HRT must consider that not all transgender people want or even have access to this therapy, and if they did, it might still be performed in different ways(4). Also, different stages of the therapy yield different results depending on the patient’s body composition, eating disorders and food consumption. In addition, having access to services that perform HRT and/or GAS is correlated with communities in terms of their access to food. Controlling such information might well be essential to better explain biological and social influences on health and nutrition in the transgender community.

Research gaps and directions for future research on gender and food

With this review, we highlight seven principal gaps we need to address to advance on food and nutrition research about transgender communities. We showed that evidence on food and nutrition in transgender persons is derived mainly from quantitative and transversal studies, without consensus about categories of analysis. Based on these findings, we propose (1) to perform more exploratory studies that enable us to formulate adequate indicators for future hypothesis tests. The evidence available so far is related to transgender people living in the context of developed countries. For this reason, we propose to the scientific community to (2) develop research in the context of the Global South, (3) analyse the influences of the diverse welfare state systems in the protection of food rights and (4) understand the historical and cultural impact of gender on the dietary habits of transgender peoples. Finally, the scientific production about this topic is concentred most in eating behaviour studies, being scarce about food security. We thus suggest (5) to explore the association between perception of food security and food consumption; (6) to indicate determinants of food insecurity in transgender communities and (7) to diversify the research approach on eating behaviour. In the next paragraphs, we explain our arguments.

We need to perform more exploratory studies (primarily ethnographic) better to understand the food and nutrition needs of transgender people. For any population, what we know is part of our generalised premises. Considering the specificities of transgender groups that we highlighted in this paper, revisiting our assumptions during our diagnosis and interventions is crucial. Exploratory studies will be useful in this task, enabling us to select proper health and well-being indicators, formulate cultural-based guidelines and understand differing outcomes of food and nutrition interventions within the transgender community.

Research on food and nutrition in the transgender community is concentrated in developed countries, with high Human Development Index, and located in the Global North. These countries lead the production of scientific knowledge worldwide and dominate the publishing market by concentrating the largest publishers, the most prominent scientific journals and the largest scientific associations. Furthermore, the older and more consolidated universities and research centres are located in the Global North and are targets for funding by the private sector(59). In this context, we see limited interest in research of problems faced mostly by societies in the Global South(60,61).

Changes in dietary standards do not happen linearly or homogeneously between the Global North and South countries. Therefore, the generalisations of studies - markedly North American and European - remain limited. Globally, we see the tendency to increasing the consumption of ultra-processed foods and decreasing food preparation in the home environment. However, this transition occurs at different moments between countries and regions. Developed countries in the context of industrialised food systems led this transition, being accompanied in the last years by those with weakened food regulation and fragile democracies(62). Like Brazil, some countries in the Global South that have maintained mostly traditional eating habits for many generations in the last decade have been facing pervasive changes in their food patterns due to the lack of regulation from the state(63). Consequently, in these countries, the impacts of dietary changes on health (e.g., non-communicable diseases) began to emerge even before overcoming fundamental problems such as malnutrition and infectious diseases, leading to an accumulation of health conditions related to food and nutrition(64).

Specific food and health needs for transgender people may also vary according to the social and health protection systems of the country or region in which they live. In Canada, the State finances some health procedures specific to transgender people, while in Japan, HRT is not covered by the health system, and the access to GAS is limited to a few hospitals. In the USA, coverage varies, requiring co-payment by the insurance status and employer participation. In countries that require direct payment or co-payment, transition costs can reach $23 000 (USD). In South Africa, only two public clinics specialise in health care for transgender people, offering HRT and few GAS services(65). In contrast, in Brazil, the entire gender transition process is provided by the Unified Health System (SUS, in Portuguese) financed by the State(66). Direct health costs in the general population are associated with the purchasing power of the individual(67) and increased food insecurity(68), affecting the food choices(69,70); in addition, access to HRT and GAS continues to influence nutritional status, body composition and eating behaviour in transgender people(22,27,42).

Cultural and historical aspects are also implicated in gender relations and can influence food and nutritional issues. Histories of colonialism and dictatorships present repercussions in violence levels and in the construction of masculinity and femininity standards(71). A democratic environment directly impacts the security and recognition of citizenship for transgender people. Currently, 27% of the countries worldwide, concentrated in the Global South, criminalise same-sex relationships and six member states of the United Nations impose the death penalty(72). A global survey carried out by Transgender Europe shows that between the years 2008 and 2018, there were 2982 murders of trans and gender-diverse people. It is noteworthy that 88% of these murders occurred in the Global South, where many countries have colonialist inheritances(73).

One study also included in our review revealed a potential association between the feel of security and the consumption of ultra-processed foods(35). Gordon et al. (23) demonstrated a relationship between gender standards and the development of eating disorders. With the current study, we see that there is a direct relationship between stigma and violence perpetrated against transgender people and their food and nutritional needs.

In the fields of food and nutrition, despite widespread discussion of gender and food and nutrition insecurity, transgender people are only rarely considered. One study in the USA reveals the severity of the prevalence of food and nutrition insecurity in this population, reaching around 79%(37). It is necessary to explore what factors are associated with this high prevalence, and how the variables are related, whether directly or indirectly. The literature records the effects of stigma on transgender people in several dimensions involving food and nutrition insecurity, but without directly measuring them: in education, health, work and in access to income(6,74). And we do not know how these indicators behave in determining food insecurity in this population.

There is still a gap in nutritional approaches for care of the transgender population with eating disorders, currently limited to focuses on psychopathological issues. Research on mental health is a trend of the studies on transgender communities due to the stigma effects on quality of life and general health. However, we need to understand better the complex nexus between life experiences and socio-cultural factors in the context of transgender people(75).

We still do not know how nutritionists and food and nutrition teams provide health services care to the transgender population. We also do not know the meanings attributed to food throughout the lives of transgender and gender nonconforming individuals. These seemingly important questions were the principal gaps discovered. We know that food is involved in a network of symbolic elements and is not limited to nutrients or their effects on health alone. For a stigma-free approach, it is necessary to train nutrition professionals to be able to explore these elements in differing gender communities.

Conclusion

We identified various research gaps, especially regarding relationships between the transgender community and food, in which illness was generally the focus of connections between them. Studies on food and nutrition for transgender people need to consider dietary practices and gender diversity in countries in the Global South since studies performed in the Global North alone possess only limited generalisation. To formulate categories of analysis which reach beyond the binary male/female gender system, exploratory studies are much needed. Despite the observed gaps, our review demonstrates that the life process of transgender people directly and/or indirectly affects relationships between the body, food and nutrition, challenging recommendations based on the binary gender system alone. This deserves to be further explored.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors thank Fillipe Pereira for his methodological support. Financial support: This work was supported by Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES), for the PhD scholarship (grant numbers 88887.505839/2020-00). Conflict of interest: There are no conflicts of interest. Ethics: No ethical approval was required for this study Authorship: S.M.G. and M.C.M.J. participated in all phases of the study. M.F.A.M. participated in the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data for the work. C.R. participated in the conception of the work, drafting and revising it critically for important intellectual content. L.R.A.N. and C.O. L. contributed to the writing and revision of the manuscript.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980021001671.

click here to view supplementary material

References

- 1. Arcelus J, Bouman WP, Van Den Noortgate W et al. (2015) Systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence studies in transsexualism. Eur Psychiatr 30, 807–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Connell R & Pearse R (2014) Gender in World Perspective, 3rd ed. Cambridge: Polity. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Human Rights Campaign. (n.d.) Glossary of terms. http://www.hrc.org/resources/glossary-of-terms (accessed November 2020).

- 4. Radix AE (2016) Medical transition for transgender individuals. In Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender Healthcare, pp. 351–361 [Eckstrand KL & Ehrenfeld JM, editors]. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hendricks ML & Testa RJ (2012) A conceptual framework for clinical work with transgender and gender nonconforming clients: an adaptation of the Minority Stress Model. Prof Psychol Res Pract 43, 460–467. [Google Scholar]

- 6. White Hughto JM, Reisner SL & Pachankis JE (2015) Transgender stigma and health: a critical review of stigma determinants, mechanisms, and interventions. Soc Sci Med 147, 222–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kanter R & Caballero B (2012) Global gender disparities in obesity: a review. Adv Nutr 3, 491–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lessa I & Rocha C (2012) Food security and gender mainstreaming: possibilities for social transformation in Brazil. Int Soc Work 55, 337–352. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Spencer RA, Rehman L & Kirk SF (2015) Understanding gender norms, nutrition, and physical activity in adolescent girls: a scoping review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 12, 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Linsenmeyer W, Drallmeier T & Thomure M (2020) Towards gender-affirming nutrition assessment: a case series of adult transgender men with distinct nutrition considerations. Nutr J 19, 74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ottrey E, Jong J & Porter J (2018) Ethnography in nutrition and dietetics research: a systematic review. J Acad Nutr Diet 118, 1903–1942.e10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lee JGL, Ylioja T & Lackey M (2016) Identifying lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender search terminology: a systematic review of health systematic reviews. PLoS One 11, e0156210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bramer WM, Rethlefsen ML, Kleijnen J et al. (2017) Optimal database combinations for literature searches in systematic reviews: a prospective exploratory study. Syst Rev 6, 245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tong A, Sainsbury P & Craig J (2007) Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Heal Care 19, 349–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. The Joanna Briggs Institute (2017) Checklist for Prevalence Studies. Adelaide: The Joanna Briggs Institute. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lo CK-L, Mertz D & Loeb M (2014) Newcastle-Ottawa Scale: comparing reviewers’ to authors’ assessments. BMC Med Res Methodol 14, 45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M et al. (2014) The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Int J Surg 12, 1495–1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Murad MH, Sultan S, Haffar S et al. (2018) Methodological quality and synthesis of case series and case reports. BMJ Evidence-Based Med 23, 60–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jacob MCM, Araújo de Medeiros MF & Albuquerque UP (2020) Biodiverse food plants in the semiarid region of Brazil have unknown potential: a systematic review. PLoS One 15, e0230936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. United Nations Development Programme (2020) 2019 Human Development Index Ranking. http://hdr.undp.org/en/content/2019-human-development-index-ranking (accessed November 2020).

- 21. Vocks S, Stahn C, Loenser K et al. (2009) Eating and body image disturbances in male-to-female and female-to-male transsexuals. Arch Sex Behav 38, 364–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Auer MK, Cecil A, Roepke Y et al. (2016) 12-months metabolic changes among gender dysphoric individuals under cross-sex hormone treatment: a targeted metabolomics study. Sci Rep 6, 37005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gordon AR, Austin SB, Krieger N et al. (2016) ‘I have to constantly prove to myself, to people, that I fit the bill’: perspectives on weight and shape control behaviors among low-income, ethnically diverse young transgender women. Soc Sci Med 165, 141–149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Guss CE, Williams DN, Reisner SL et al. (2017) Disordered weight management behaviors, nonprescription steroid use, and weight perception in transgender youth. J Adolesc Heal Off Publ Soc Adolesc Med 60, 17–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Henderson ER, Jabson J, Russomanno J et al. (2019) Housing and food stress among transgender adults in the United States. Ann Epidemiol 38, 42–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Himmelstein MS, Puhl RM & Watson RJ (2019) Weight-based victimization, eating behaviors, and weight-related health in Sexual and Gender Minority Adolescents. Appetite 141, 104321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hiraide M, Harashima S, Yoneda R et al. (2017) Longitudinal course of eating disorders after transsexual treatment: a report of two cases. Biopsychosoc Med 11, 32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jones BA, Haycraft E, Bouman WP et al. (2018) Risk factors for eating disorder psychopathology within the treatment seeking transgender population: the role of cross-sex hormone treatment. Eur Eat Disord Rev 26, 120–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kirby SR & Linde JA (2020) Understanding the nutritional needs of transgender and gender-nonconforming students at a Large Public Midwestern University. Transgender Heal 5, 33–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Linsenmeyer WR & Rahman R (2018) Diet and nutritional considerations for a FtM transgender male: a case report. J Am Coll Health 66, 533–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Millington K, Schulmeister C, Finlayson C et al. (2020) Physiological and metabolic characteristics of a cohort of transgender and gender-diverse youth in the United States. J Adolesc Heal 67, 376–383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Nagata JM, Murray SB, Compte EJ et al. (2020) Community norms for the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q) among transgender men and women. Eat Behav 37, 101381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Avila JT, Golden NH & Aye T (2019) Eating disorder screening in transgender youth. J Adolesc Heal Off Publ Soc Adolesc Med 65, 815–817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Peterson CM, Toland MD, Matthews A et al. (2020) Exploring the eating disorder examination questionnaire in treatment seeking transgender youth. Psychol Sex Orientat Gend Divers 7, 304–315. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pistella J, Ioverno S, Rodgers MA et al. (2020) The contribution of school safety to weight-related health behaviors for transgender youth. J Adolesc 78, 33–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ristori J, Fisher AD, Castellini G et al. (2019) Gender dysphoria and anorexia nervosa symptoms in two adolescents. Arch Sex Behav 48, 1625–1631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Russomanno J & Jabson Tree JM (2020) Food insecurity and food pantry use among transgender and gender non-conforming people in the Southeast United States. BMC Public Health 20, 590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Russomanno J, Patterson JG & Jabson JM (2019) Food insecurity among transgender and gender nonconforming individuals in the southeast united states: a qualitative study. Transgender Heal 4, 89–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Schier HE & Linsenmeyer WR (2019) Nutrition-related messages shared among the online transgender community: a Netnography of YouTube vloggers. Transgender Heal 4, 340–349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Simone M, Askew A, Lust K et al. (2020) Disparities in self-reported eating disorders and academic impairment in sexual and gender minority college students relative to their heterosexual and cisgender peers. Int J Eat Disord 53, 513–524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Testa RJ, Rider GN, Haug NA et al. (2017) Gender confirming medical interventions and eating disorder symptoms among transgender individuals. Heal Psychol Off J Div Heal Psychol Am Psychol Assoc 36, 927–936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Turan Ş, Aksoy Poyraz C, Usta Sağlam NG et al. (2018) Alterations in body uneasiness, eating attitudes, and psychopathology before and after cross-sex hormonal treatment in patients with female-to-male gender dysphoria. Arch Sex Behav 47, 2349–2361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Watson RJ, Veale JF & Saewyc EM (2017) Disordered eating behaviors among transgender youth: probability profiles from risk and protective factors. Int J Eat Disord 50, 515–522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Beaty L, Trees N & Mehler P (2017) Recurrent persistent hypophosphatemia in a male-to-female transgender patient with anorexia nervosa: case report. Int J Eat Disord 50, 606–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Witcomb GL, Bouman WP, Brewin N et al. (2015) Body image dissatisfaction and eating-related psychopathology in trans individuals: a matched control study. Eur Eat Disord Rev 23, 287–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Bell K, Rieger E & Hirsch JK (2019) Corrigendum: eating disorder symptoms and proneness in gay men, lesbian women, and transgender and gender non-conforming adults: comparative levels and a proposed mediational model. Front Psychol 9, 2228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Brewster ME, Velez BL, Breslow AS et al. (2019) Unpacking body image concerns and disordered eating for transgender women: the roles of sexual objectification and minority stress. J Couns Psychol 66, 131–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Bishop A, Overcash F, McGuire J et al. (2020) Diet and physical activity behaviors among adolescent transgender students: school survey results. J Adolesc Heal Off Publ Soc Adolesc Med 66, 484–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Diemer EW, Grant JD, Munn-Chernoff MA et al. (2015) Gender identity, sexual orientation, and eating-related pathology in a national sample of college students. J Adolesc Heal Off Publ Soc Adolesc Med 57, 144–149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Diemer EW, White Hughto JM, Gordon AR et al. (2018) Beyond the binary: differences in eating disorder prevalence by gender identity in a transgender sample. Transgender Heal 3, 17–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Duffy ME, Henkel KE & Earnshaw VA (2016) Transgender clients’ experiences of eating disorder treatment. J LGBT Issues Couns 10, 136–149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Ålgars M, Alanko K, Santtila P, et al. (2012) Disordered eating, gender identity disorder: a qualitative study. Eat Disord 20, 300–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Bandini E, Fisher AD, Castellini G et al. (2013) Gender identity disorder and eating disorders: similarities and differences in terms of body uneasiness. J Sex Med 10, 1012–1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Khoosal D, Langham C, Palmer B et al. (2009) Features of eating disorder among male-to-female transsexuals. Sex Relatsh Ther 24, 217–229. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Algars M, Santtila P & Sandnabba NK (2010) Conflicted gender identity, body dissatisfaction, and disordered eating in adult men and women. Sex Roles 63, 118–125. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Vilas MVA, Rubalcava G, Becerra A et al. (2014) Nutritional status and obesity prevalence in people with gender dysphoria. AIMS Public Heal 1, 137–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Adams N, Pearce R, Veale J et al. (2017) Guidance and ethical considerations for undertaking transgender health research and institutional review boards adjudicating this research. Transgender Heal 2, 165–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Puckett JA, Brown NC, Dunn T et al. (2020) Perspectives from transgender and gender diverse people on how to ask about gender. LGBT Heal 7, 305–311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Collyer FM (2018) Global patterns in the publishing of academic knowledge: global North, global South. Curr Sociol 66, 56–73. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Reidpath DD & Allotey P (2019) The problem of ‘trickle-down science’ from the Global North to the Global South. BMJ Glob Heal 4, e001719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.International Panel of Experts on Sustainable Food Systems (IPES-Food) (2017) Unravelling the food–health nexus addressing practices, political economy, and power relations to build healthier food systems. http://www.ipes-food.org/_img/upload/files/Health_ExecSummary(1).pdf/ (accessed December 2020).

- 62. Baker P, Machado P, Santos T et al. (2020) Ultra-processed foods and the nutrition transition: global, regional and national trends, food systems transformations and political economy drivers. Obes Rev 21, e13126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Monteiro CA & Cannon G (2012) The impact of transnational “big food” companies on the south: a view from Brazil. PLoS Med 9, e1001252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Vorster E & Bourne LT (2016) The nutrition transition in developing countries. In Community Nutrition for Developing Countries, pp. 54–63 [Temple NJ & Steyn N, editors]. Athabasca, Canada: Au press. [Google Scholar]

- 65. Koch JM, McLachlan C, Victor CJ et al. (2020) The cost of being transgender: where socio-economic status, global health care systems, and gender identity intersect. Psychol Sex 11, 103–119. [Google Scholar]

- 66. Popadiuk GS, Oliveira DC & Signorelli MC (2017) The National Policy for Comprehensive Health of Lesbians, Gays, Bisexuals and Transgender (LGBT) and access to the Sex Reassignment Process in the Brazilian Unified Health System (SUS): progress and challenges. Cien Saude Colet 22, 1509–1520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Abad-Segura E, González-Zamar M-D, Gómez-Galán J et al. (2020) Management accounting for healthy nutrition education: meta-analysis. Nutrients 12, 3715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Berkowitz SA, Basu S, Meigs JB et al. (2018) Food insecurity and health care expenditures in the United States, 2011–2013. Health Serv Res 53, 1600–1620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Boek S, Bianco-Simeral S, Chan K et al. (2012) Gender and race are significant determinants of students’ food choices on a college campus. J Nutr Educ Behav 44, 372–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Glanz K, Basil M, Maibach E et al. (1998) Why Americans eat what they do. J Am Diet Assoc 98, 1118–1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Banerjee P & Connell R (2018) Gender theory as southern theory. In Handbooks of Sociology and Social. Research, pp. 57–68 [Risman BJ, Froyum CM, & Scarborough WJ, editors]. Switzerland: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 72. International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association (ILGA): Lucas Ramón Mendos (2019) State-Sponsored Homophobia 2019. Geneva: ILGA World. [Google Scholar]

- 73. Berredo L, Arcon A, Regalado AG et al. (2018) Global Trans Perspectives on Health and Wellbeing: TvT Community Report. Berlin: Transgender Europe (TGEU).

- 74. Hatzenbuehler ML & Pachankis JE (2016) Stigma and minority stress as social determinants of health among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth. Pediatr Clin North Am 63, 985–997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Reisner SL, Poteat T, Keatley J et al. (2016) Global health burden and needs of transgender populations: a review. Lancet 388, 412–436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980021001671.

click here to view supplementary material