Abstract

Objective:

To estimate the burden of excess weight in Brazilian adolescents.

Design:

Systematic review with meta-analysis.

Setting:

We searched the literature in four databases (MEDLINE/PubMed, EMBASE, SciELO and LILACS). Studies were included if they had cross-sectional or cohort design and enrolled Brazilian adolescents. Studies based on self-reported measures were excluded. Random effect models were used to calculate prevalence estimates and their 95 % CI.

Participants:

Brazilian adolescents (10 to 19 years old).

Results:

One hundred and fifty-one studies were included. Trend analyses showed a significant increase in the prevalence of excess weight in the last decades: 8·2 % (95 % CI 7·7, 8·7) until year 2000, 18·9 (95 % CI 14·7, 23·2) from 2000 to 2009, and 25·1 % (95 % CI 23·4, 26·8) in 2010 and after. A similar temporal pattern was observed in the prevalence of overweight and obesity separately. In sensitivity analyses, lower prevalence of excess weight was found in older adolescents and those defined using International Obesity Task Force cut-off points. The Southeast and South regions had the highest prevalence of excess weight, overweight and obesity. No significant difference in prevalence by sex was found, except for studies before the year 2000.

Conclusions:

The prevalence of overweight and obesity in Brazilian adolescents is high and continues to rise. Public policies on an individual level and targeting modifications in the obesogenic environment are necessary.

Keywords: Obesity, Adolescence, Brazil, Prevalence

Obesity in early life has immediate consequences on health, such as dyslipidemia hypertension, abnormal glucose tolerance and other risk factors for cardiovascular disease (CVD)(1,2). It is a precursor of adulthood obesity(3), leading to development of cardiometabolic risk factors like atherosclerosis and type 2 diabetes(1,4). According to data from the World Health Organisation (WHO), in 2012, chronic non-communicable diseases were responsible for 38 million deaths worldwide(5). From an economic point of view, chronic non-communicable diseases are responsible for high public financial expenditures, with obesity being especially linked to sky-rocketing medical costs(6).

In the last decades, the global prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adolescents has exponentially increased(7). In 2008, it was estimated that 170 million people less than 18 years old were classified with overweight or obesity(7); and projection models show that, by 2030, 30 % of children and adolescents will be affected by these conditions in the USA(8). Estimates by WHO show that most youths with excess weight live in low- and middle-income countries, where the rates have been increasing even faster compared to high-income countries(9).

In Brazil, overweight and obesity among youth is an important public health concern due to its increasing prevalence. Data from the Family Budget Survey (POF), conducted between 1974 and 2009, show that obesity among adolescents increased from 0·4 to 5·9 % in boys and from 0·7 to 4·0 % in girls(10). More recently, the Study of Cardiovascular Risks in Adolescents (ERICA), which evaluated 73 399 Brazilian adolescents aged 12 to 17 years, revealed that 17·1 % and 8·4 % of adolescents had overweight and obesity, respectively(11).

Differences between Brazilian regions are striking in many ways, with social, demographic, cultural and economic factors particularly influencing nutritional status. The South and Southeast are more developed and industrialised regions, Midwest is in development trough agribusiness, while the North and Northeast regions are characterised by the highest social inequalities in Brazil. Access to healthcare services is much lower in the North and Northeast regions compared to the rest of the country. Despite very different epidemiological profiles, regional information about the trends in prevalence of excess weight among adolescents are scarce. A previous systematic review that included 28 Brazilian studies showed an overall prevalence of obesity among adolescents of 14·1 %, but results were not stratified by region or decades, therefore making it difficult to generalise such rate for the whole country(12). The diversity between Brazilian geographical areas highlights the necessity of collecting data from studies conducted in different cities and states of Brazil in order to obtain a better epidemiological profile of youth obesity across the country during the past decades.

In order to have a better understanding of excess weight trends in Brazilian adolescents, we performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies that presented data about weight status in this population. Our objective was to estimate the prevalence of overweight and obesity in Brazilian adolescents, considering regional and temporal variations. We hypothesised that overweight and obesity would significantly increase over the years in all regions of Brazil.

Methods

The protocol for this review was registered and published on the Prospero database (Registration number: CRD42018107055). The report of this systematic review follows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement(13,14).

Search strategy

The search strategy was performed in Portuguese and English languages, without restriction of publication data, by the main investigator. The literature search combined the following keywords: overweight, obesity, adolescents and Brazil. The terms were searched in four databases: MEDLINE (Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online/PubMed), EMBASE (Elsevier), Scientific Electronic Library Online (SciELO) and Literatura Latino-Americana e do Caribe em Ciências da Saúde (LILACS). Full search strategy is shown in the supplementary material (Table S1). All potentially eligible studies were considered for review. Duplicate studies were excluded. The software EndNote version X7 (Thomson Reuters, New York, NY) was used for reference selection management. The last search was performed in June 2020.

Study eligibility

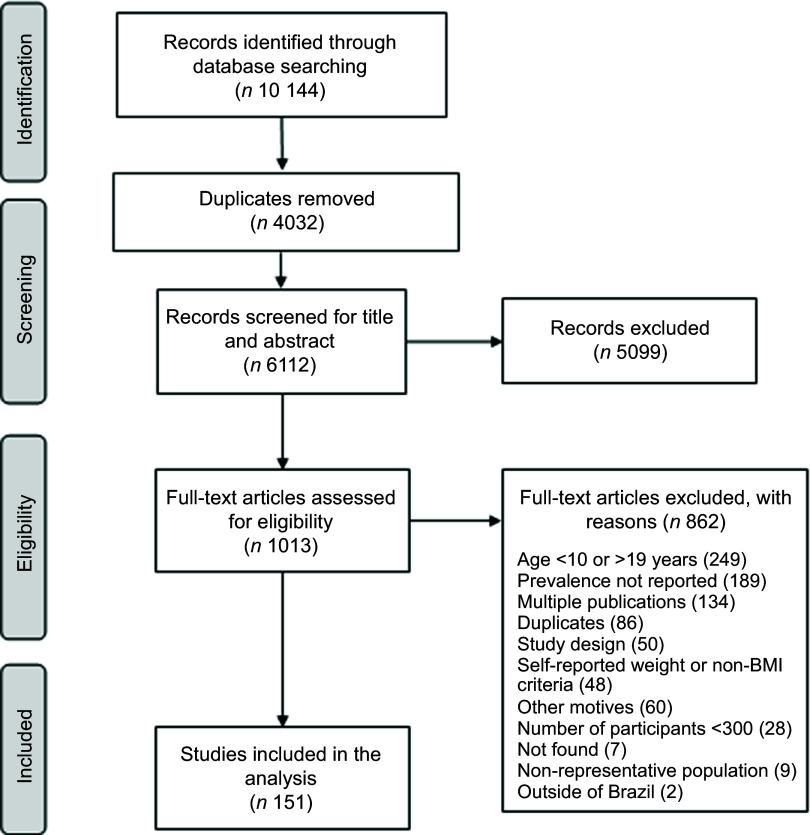

Two pairs of reviewers (MS and MRG; JAR and MM) analysed study eligibility independently. Figure 1 shows the flow diagram of the studies included in the meta-analysis. The studies were selected based on the following criteria: cross-sectional and cohort studies that reported the prevalence of overweight/obesity among Brazilian adolescents (10–19 years old). Weight and height had to be measured to calculate the BMI; studies based on self-reported data were excluded.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of study selection.

Populations in the studies had to be selected through random sampling or census, and studies that included less than 300 individuals were excluded. A sample size calculation was performed considering the following parameters: prevalence of overweight/obesity of 25 %(11), power of 80 % and confidence level of 95 %. These parameters required a sample of around 300 adolescents. This criterion was adopted to help us in the screening processes, avoiding studies with non-representative sample at local level, at least, or those with a large margin of error.

Additionally, studies that assessed only specific subgroups not representative of its geographical strata were considered ineligible. Systematic reviews, narrative reviews, clinical trials, case–control and case reports studies, as well as studies using overweight/obesity diagnostic criteria for adults were excluded from this review. Studies in English and Portuguese were included. A third investigator (FVC) solved disagreements between reviewers.

Data extraction

Two pairs of reviewers (MS and MRG; JAR and MM) separately evaluated the studies for data extraction. Titles and abstracts were reviewed and publications were selected for reading in full, if they presented data according to the inclusion/exclusion criteria or had insufficient information in the abstract to make a decision. Studies from the same population were assessed and the article with more details was included. In relation to studies with insufficient information, a request was sent to the authors; if they did not reply, the study was excluded from this review.

Data were entered in a pretested Microsoft Office Excel™ spreadsheet based on the Strengthening in Epidemiology Statement (STROBE) checklist(15). The absolute, rather than relative value of each variable, was obtained. Any discordance between the data extracted was discussed until consensus was reached. Captured variables included study name, date of publication, year of data collection, study design and type (household survey, school-based survey, etc), age range, region, diagnostic criteria for overweight and obesity and estimated prevalence of overweight and obesity (overall and by sex).

Risk of bias

We assessed the risk of bias for each selected study using a ten-item tool that was specifically developed for population-based prevalence studies(16). The tool is divided in two domains – external validity (four items) and internal validity (six items). After evaluation of the ten items, each item received a score of 1 (yes) or 0 (no). According to overall scores, a summary assessment deemed a study to be at low (9–10), moderate (6–8) or high (≤5) risk of bias.

Statistical analysis

Random effect models were used to calculate prevalence estimates and their 95 % CI. Results are presented by decades (before year 2000, years 2000 to 2009, and year 2010 and after). Sensitivity analyses were performed by sex, age group, macroregion and diagnostic criteria. Double arcsine transformation was used to handle distribution asymmetry related to different prevalence measures(17). Continuity correction was used for adjustment when a discrete distribution was approximated by a continuous distribution. Pooled values were then converted to prevalence. Chi-square test was used to determine differences in prevalence rates among different decades. The Cochran chi-square and I 2 tests were used to evaluate statistical heterogeneity and consistency among the studies. Values of I 2 higher than 50 % were considered an indication of high heterogeneity; however, high heterogeneity is expected in meta-analysis of prevalence studies. Statistical analyses were performed using MetaXL (Epi-Gear International, Sunrise Beach, Australia), an Excel-based comprehensive program for meta-analysis.

Results

The search retrieved 10 144 articles in 4 databases, of which 4032 were duplicates and were excluded. Additional 5099 articles were removed based on title and abstracts, and 1013 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility, of which 151 (9 187 431 individuals) met all the inclusion criteria (Fig. 1).

The main characteristics of the included studies are described in Table S2. Most studies had a cross-sectional design (146 studies, 97 %). Sample sizes varied substantially with a median of 1009 adolescents. Few studies collected the data before the 2000s (nine studies, 6 %). The most used criteria to define overweight or obesity were from the WHO (80 studies, 53 %).

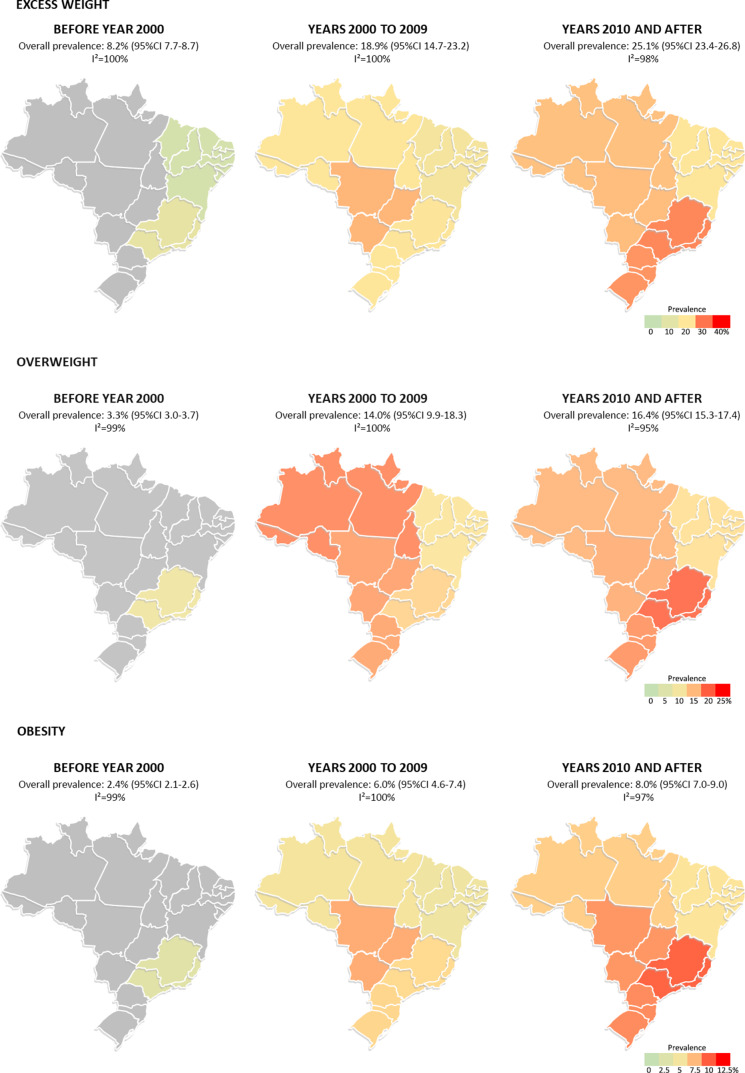

A meta-analysis was conducted according to the excess weight category and temporal trends by decades. Changes in the prevalence of excess weight over time and by Brazilian regions are shown in Fig. 2. The overall prevalence of overweight/obesity, overweight and obesity was 20·6 % (95 % CI 19·6, 21·5, I 2 100 %), 14·5 % (95 % CI 13·5, 15·4, I² 100 %) and 6·6 % (95 % CI 6·2, 7·0, I² 100 %), respectively. In trend analyses, we observed a significant increase in the prevalence of overweight/obesity in the last decades (8·2 % (95 % CI 7·7, 8·7, I² 100 %) until 2000s, 18·9 (95 % CI 14·7, 23·2, I² 100 %) in the 2000s and 25·1 % (95 % CI 23·4, 26·8, I² 98 %) in the 2010s). Similar results are observed for the trends in the prevalence of overweight and obesity when analysed separately. Complete forest plots for overweight/obesity, overweight and obesity, showing all studies included, can be found on the Online Supplementary Figs. S1, S2 and S3.

Fig. 2.

Prevalence of excess weight (overweight/obesity), overweight and obesity by time period in Brazilian macroregions. Excess weight: a) Before year 2000: Northeast (n 3, 5·3 %; 95 % CI 2·5, 8·9, I² 99 %) and Southeast (n 8, 11·9 %; 95 % CI 6·5, 18·1, I² 99 %). b) Years 2000 to 2009: North (n 3, 19·4 %; 95 % CI 13·5, 25·7, I² 98 %), Northeast (n 14, 16·4 %; 95 % CI 13·9, 19·1, I² 97 %), Midwest (n 2, 24·2 %; 95 % CI 17·9, 30·9, I² 97 %), Southeast (n 27, 19·1 %; 95 % CI 16·7, 21·6, I² 98 %) and South (n 23, 19·6 %; 95 % CI 16·5, 22·9, I² 98 %). c) Years 2010 and after: North (n 5, 23·3 %; 95 % CI 21·3, 25·5, I² 82 %), Northeast (n 18, 19·6 %; 95 % CI 17·0, 22·5, I² 97 %), Midwest (n 4, 23·6 %; 95 % CI 22·2, 25·1, I² 51 %), Southeast (n 19, 28·2 %; 95 % CI 25·8, 30·6, I² 95 %) and South (n 28, 27·1 %; 95 % CI 24·2, 30·0, I² 97 %). Overweight: a) Before year 2000: Southeast (n 4, 9·0 %; 95 % CI 3·5, 15·5, I² 98 %). b) Years 2000 to 2009: North (n 2, 17·7 %; 95 % CI 9·6, 26·8, I² 97 %), Northeast (n 10, 11·7 %; 95 % CI 9·8, 13·7, I² 94 %), Midwest (n 2, 16·4 %; 95 % CI 12·8, 20·1, I² 93 %), Southeast (n 21, 13·6 %; 95 % CI 12·1, 15·2, I² 95 %) and South (n 13, 16·1 %; 95 % CI 13·9, 18·3, I² 94 %). c) Years 2010 and after: North (n 2, 15·2 %; 95 % CI 14·7, 15·8, I² 0 %), Northeast (n 14, 12·9 %; 95 % CI 11·1, 14·8, I² 94 %), Midwest (n 4, 15·6 %; 95 % CI 14·3, 17·0, I² 59 %), Southeast (n 12, 19·4 %; 95 % CI 18·1, 20·8, I² 85 %) and South (n 18, 17·1 %; 95 % CI 15·3, 19·1, I² 94 %). Obesity: a) Before year 2000: Southeast (n 3, 2·9 %; 95 % CI 1·3, 4·8, I² 90 %). b) Years 2000 to 2009: North (n 2, 5·2 %; 95 % CI 4·0, 6·5, I² 59 %), Northeast (n 10, 4·5 %; 95 % CI 2·9, 6·3, I² 97 %), Midwest (n 2, 7·8 %; 95 % CI 5·1, 10·7, I² 93 %), Southeast (n 23, 6·6 %; 95 % CI 5·2, 8·1, I² 97 %) and South (n 15, 6·7 %; 95 % CI 5·3, 8·3, I² 95 %). c) Years 2010 and after: North (n 3, 6·9 %; 95 % CI 5·8, 8·1, I² 20 %), Northeast (n 15, 6·0 %; 95 % CI 4·9, 7·2, I² 93 %), Midwest (n 5, 8·4 %; 95 % CI 7·1, 9·8, I² 79 %), Southeast (n 12, 9·8 %; 95 % CI 7·9, 11·9, I² 97 %) and South (n 19, 8·7 %; 95 % CI 6·7, 10·9, I² 98 %).

In relation to regional estimates, only the Northeast and Southeast regions had data available before year 2000 invalidating comparisons among regions at this time. Between years 2000 and 2009 and after 2010, the Northeast had the lowest prevalence of excess weight, overweight and obesity compared to the other regions. A small number of studies from the Midwest and North regions were included in the last two time periods. The highest prevalence of all weight groups in years 2010 and after was found in the Southeast region, followed by the South region (Fig. 2).

Prevalence rates of excess weight category and their 95 % CI by sex, age group and diagnostic criteria are presented in Table 1. The overall prevalence of overweight and obesity was similar among sexes, except for studies before year 2000, for which females had a higher prevalence of excess weight. Studies that enrolled older adolescents and those adopting International Obesity Task Force (IOTF) cut-off points after year 2000 reported lower prevalence ratios of excess weight compared to other categories. High statistical heterogeneity was identified in all analyses.

Table 1.

Subgroup meta-analyses of excess weight, overweight and obesity by decades

| Time trends | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before 2000 | 2000–2009 | 2010 and after | ||||||||||

| Variables | n | % | 95 % CI | I²% | n | % | 95 % CI | I²% | n | % | 95 % CI | I²% |

| Excess weight (overweight/obesity) | ||||||||||||

| Sex | ||||||||||||

| Female | 10 | 11·9 | 8·4–15·7 | 99 | 46 | 19·2 | 17·7–20·7 | 96 | 40 | 23·8 | 22·1–25·5 | 95 |

| Male | 13 | 4·6 | 4·4–5·0 | 99 | 46 | 20·7 | 14·9–26·8 | 100 | 39 | 24·8 | 22·4–27·1 | 97 |

| Age group, years | ||||||||||||

| 10–14 | 1 | – | – | 26 | 20·5 | 18·1–23·0 | 98 | 17 | 28·3 | 24·6–32·0 | 98 | |

| 15–19 | 5 | 4·7 | 4·4–5·1 | 99 | 19 | 14·2 | 9·0–19·8 | 100 | 12 | 18·0 | 15·3–20·9 | 97 |

| Diagnostic criteria | ||||||||||||

| IOTF | 7 | 9·2 | 5·7–13·1 | 99 | 23 | 17·2 | 15·0–19·6 | 97 | 16 | 21·7 | 19·1–24·3 | 95 |

| Must et al. (27) | 1 | – | – | 3 | 21·1 | 17·8–24·6 | 87 | – | – | – | ||

| Conde and Monteiro(26) | – | – | – | 8 | 22·3 | 18·4–26·4 | 98 | 5 | 26·1 | 14·8–38·4 | 99 | |

| WHO | 4 | 4·4 | 4·1–4·7 | 99 | 33 | 19·3 | 13·0–26·1 | 100 | 45 | 26·6 | 24·3–28·9 | 98 |

| CDC | 1 | – | – | 5 | 16·9 | 10·4–24·0 | 98 | 5 | 21·9 | 18·0–26·0 | 92 | |

| Overweight | ||||||||||||

| Sex | ||||||||||||

| Female | 3 | 10·9 | 3·9–19·2 | 95 | 28 | 14·7 | 13·3–16·2 | 94 | 22 | 16·4 | 15·2–17·7 | 90 |

| Male | 6 | 2·3 | 2·1–2·6 | 99 | 29 | 13·8 | 8·3–19·7 | 100 | 22 | 15·3 | 13·7–16·9 | 94 |

| Age group, years | ||||||||||||

| 10–14 | 1 | – | – | 18 | 15·4 | 13·2–17·7 | 98 | 10 | 17·8 | 15·2–20·4 | 96 | |

| 15–19 | 4 | 1·8 | 1·7–2·0 | 99 | 10 | 10·7 | 4·3–18·1 | 100 | 8 | 12·6 | 10·2–15·1 | 93 |

| Diagnostic criteria | ||||||||||||

| IOTF | 2 | 14·5 | 11·4–17·8 | 72 | 16 | 14·2 | 12·4–16·1 | 92 | 9 | 14·5 | 12·3–16·8 | 92 |

| Must et al. (27) | – | – | – | 2 | 13·6 | 12·0–15·2 | 46 | – | – | – | ||

| Conde and Monteiro(26) | – | – | – | 6 | 19·5 | 17·5–21·6 | 92 | 2 | 11·7 | 6·0–18·3 | 93 | |

| WHO | 3 | 1·7 | 1·6–1·8 | 98 | 23 | 13·1 | 7·5–19·2 | 100 | 33 | 17·7 | 16·7–18·9 | 93 |

| CDC | 1 | – | – | 4 | 11·5 | 4·3–20·0 | 98 | 3 | 11·1 | 10·4–12·1 | 0 | |

| Obesity | ||||||||||||

| Sex | ||||||||||||

| Female | 2 | 4·2 | 3·1–5·3 | 0 | 32 | 6·1 | 5·3–6·9 | 92 | 23 | 6·5 | 5·6–7·5 | 93 |

| Male | 5 | 2·2 | 2·0–2·5 | 99 | 33 | 6·6 | 4·6 −8·8 | 100 | 23 | 7·8 | 6·3–9·3 | 97 |

| Age group, years | ||||||||||||

| 10–14 | 1 | – | – | 19 | 6·5 | 5·0–8·1 | 98 | 11 | 9·7 | 7·2–12·5 | 98 | |

| 15–19 | 4 | 2·2 | 1·9–2·5 | 100 | 10 | 3·4 | 1·9–5·2 | 98 | 9 | 5·3 | 4·0–6·6 | 91 |

| Diagnostic criteria | ||||||||||||

| IOTF | 1 | – | – | 18 | 4·9 | 3·8–6·1 | 93 | 9 | 4·9 | 3·7–6·2 | 91 | |

| Must et al. (27) | – | – | – | 2 | 7·4 | 3·9–11·8 | 94 | – | – | – | ||

| Conde and Monteiro(26) | – | – | – | 6 | 5·3 | 3·5–7·4 | 97 | 2 | 3·3 | 2·0–4·9 | 64 | |

| WHO | 3 | 2·2 | 1·9–2·5 | 100 | 24 | 6·7 | 4·4–9·3 | 100 | 33 | 9·4 | 8·3–10·6 | 97 |

| CDC | 1 | – | – | 5 | 6·5 | 2·4–11·5 | 96 | 3 | 7·0 | 6·4–7·8 | 0 | |

IOTF, International Obesity Task Force; CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Risk of bias assessment is presented in online Supplementary Table S3. Overall risk of bias was considered low in 108 studies (71·5 %), moderate in 42 studies and high in 1 study. All studies had data collected using the same mode and directly from the subjects, had an acceptable case definition, measured the parameter of interest with an instrument shown to have validity and reliability, and had appropriate numerators and denominators for the parameter of interest. Most studies selected a population that was nationally representative in the parameters of interest (66·9 %) and had a sampling frame representative of the target population (88·7 %). A census or a random form of selection was used in 115 studies (76·2 %) and the likelihood of non-response bias was minimal in 77 studies (51·0 %).

Discussion

In this systematic review, we identified 151 studies reporting rates of excess weight in Brazilian adolescents, with data collected from 1974 to 2018. Prevalence of excess weight ranged from 2·2 % to 44·4 %, and an increase could be seen when comparing information from more recent to older studies. Populations were included from household surveys, birth cohorts and school-based samples, and only twelve studies included individuals from more than one macroregion in Brazil.

Individual cross-sectional studies have hinted the rising trends of overweight and obesity among this age group in different countries(18,19), but representative data of trends about the prevalence of overweight and obesity among Brazilian adolescents were limited. To fill this gap, we performed a systematic review focused on adolescents from all regions in Brazil, and we show separate data by decades of data collection. In general, we observed an increase in the prevalence of overweight and obesity among Brazilian adolescents since the 70s. The high statistical heterogeneity found was expected, as previous meta-analyses of prevalence studies showed(12,20). In our analysis, the heterogeneity can be due to differences between samples of the studies in many characteristics, such as age (some included adolescents from all ages, others included only those with 10 to 13 years or 17 and older), ethnic background (some studies were made with indigenous populations), criteria for excess weight (five different classifications were observed) and type of study (school-based, household survey or cohort).

In the last decades, Brazil and other middle-income countries have experienced a quick transition in food availability and eating habits. Until recently, the most prevalent nutritional problem in Brazilian children and adolescents was underweight/undernutrition, especially in the poorer and less developed regions of the country(21). However, due to a rapid industrial expansion and changes in lifestyle (such as increase in sedentary time(22) and consumption of ultra-processed foods(23)), a double disease burden can be seen – undernutrition is still present in many areas, but obesity-related health problems are higher than ever(24). Countries like India and China, which also underwent significant socio-economic changes in a small amount of time, have similar growing trends in excess weight in youth. From the 80s to the last 10 years, for an example, overweight rates increased from 1·8 % to over 13 % in Chinese children and adolescents(25).

In this systematic review, we present an overall prevalence of excess weight from studies that have adopted different criteria to classify adolescents with overweight and obesity, one of them specifically made using only Brazilian children(26). Classification based on the article by Must et al(27) was the least used. Classification based on WHO references(28) was the most commonly used, especially in studies published since 2009. Criteria by IOTF for overweight/obesity(29) was the preferred before year 2000. It is possible to consider that adding prevalence from diverse cutoffs is a limitation and could lead to imprecise results; however, the prevalence for overweight/obesity still exponentially increased in last decades when we analyze separately studies that used WHO reference curves (4.4 % until year 2000 to 26.6 % in the 2010s) and IOTF criteria (9.2 % to 21.7 %), despite including a smaller number of articles.

In subgroup analysis, the prevalence of excess weight varied greatly among macroregions, reflecting the health inequalities between them. In the literature, many studies show that associations between socio-economic status (SES) and rates of obesity depend on local characteristics – people with higher SES are less likely to be overweight or obese in high-income countries, but more likely in lower-income countries(30). In a continental sized country such as Brazil, it is important to address how significant differences among regions can influence nutritional patterns. In our study, we found a positive association between SES and rates of excess weight comparing regions – prevalence was lower in the Northeast region across all decades and higher in the South and Southeast regions in the last decade. States from the Northeast region have the lowest Human Development Index (HDI) in the country, and nutritional transition at these places is relatively recent or concurrent, with underweight still being an important public health concern. Conversely, at the South and Southeast regions, comprising states that have the highest HDI of the country, these changes were observed decades ago, and ultra-processed foods are more easily accessible(24,31). This dietary pattern has been previously reported in adolescents – in the ERICA study, higher SES was associated with greater consumption of unhealthy foods, such as sugary drinks and snacks(32).

The prevalence of overweight/obesity in this study was similar and increased across decades in both sexes; however, girls had higher rates of excess weight before year 2000 (11·9 % v. 4·6 %). This can be partially explained due to the fact that, in this period, two big studies included only boys at older age (17–19 years) from the Brazilian Army database. Similar results by sex are observed in a recent country-wide survey in Brazil(33), supporting that prevention polices against obesity should be conducted independently of sex. Finally, analyses comparing group ages showed that younger adolescents had higher prevalence of excess weight compared to their older counterparts. This can be directly related to puberty and its effect on acquisition of fat-free mass, reaching the highest levels at peak height growth velocity(34).

Treatment of obesity in a health system usually involves recommendation of lifestyle modifications (increase physical activity, decrease sugar and fat consumption), pharmacological therapy and, in selected cases, bariatric surgery. Nevertheless, obesity rates continue to grow alarmingly worldwide. This can be attributed to the fact that the ‘pressure’ from the obesogenic environment is still the same, and therefore interventions should also try to change socio-economic, political and cultural context involving excess weight. Efforts such as clear nutritional labelling in packages or decrease in percentual of fats are commonly accepted by decision-makers and food industry. However, regulation of food advertising, taxing or banning energy-dense and nutrition-poor foods sold in schools find a barrier for implementation, mostly due to commercial interests(35). Actions for prevention of obesity during childhood also involve the same modifications in public policies. Only when obesity is approached in an interdisciplinary way beyond the health sector, we will have a real chance of altering its repercussions later in life.

Nonetheless, it is important to consider regional access to healthcare services and economical power when defining prevention strategies, as they vary greatly among Brazilian regions. Populations from the North and Northeast regions, especially those with lower SES, have more difficulty in reaching the healthcare system, and when they do, resources are scarce(36). Additionally, access to healthy foods, such as vegetables and fruits, can be limited, as they have higher prices compared to ultra-processed foods. In contrast, adolescents from the South and Southeast regions have higher prevalence of excessive screen(22) and sitting time(37), as well as higher access to physical education classes. These inequity patterns show that there is no simple or single solution to tackle this health problem in Brazil. Public policies need to be specific for each region, considering their strengths and weaknesses, in order to be effective. In the South and Southeast, the higher accessibility to infrastructure (sports courts, tracks and swimming pools) can be used to diminish sedentary behaviour and to promote physical activity, while in the North and Northeast it is essential to improve nutritional composition and overall access to healthcare services.

Our study has some limitations. The number of studies from before the 2000s was much smaller than those from other decades, and more than half were composed by adolescents from the Southeast region of Brazil; therefore, the prevalence from this period may not be accurate. There was also a low representation of individuals from the North and Midwest regions, especially before 2010. This poor coverage of epidemiological changes in some Brazilian regions restricts the evaluation of national prevalence of excess weight over time. Further studies in these macroregions are required to correctly demonstrate racial, cultural and socio-economic diversity of this nation. Differences and changes in diagnosis criteria over time among the studies may also limit the interpretation of our results. High heterogeneity was found in all analyses; however, this is expected when gathering results from more than a hundred studies that used multiple criteria and included individuals from different regions and age groups.

Conclusions

Despite inherent limitations from gathering data of studies from a continent-sized country such as Brazil, our findings can be considered the most recent trend estimates of excess weight in adolescents, and they clearly show that the prevalence of overweight and obesity is alarmingly increasing in recent years. This situation warrants public health interventions, which should be based mainly on prevention of overweight during the adolescence and its health consequences later in life.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: Not applicable. Financial support: This study was financed in part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior – Brasil (CAPES) – Finance Code 001 and National Counsel of Technological and Scientific Development (CNPq) (grant: 440822/2017–3). Conflict of interest: There are no conflicts of interest. Authorship: MS, FVC, LCP and BDS conceived and designed the analysis. MS, JdAR, DSS, MMM, GZ and MRG collected the data. MS and FVC performed the analysis. All authors contributed to writing the paper. Ethics of human subject participation: Not applicable.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980021001464.

click here to view supplementary material

References

- 1. McCrindle BW (2015) Cardiovascular consequences of childhood obesity. Can J Cardiol 31, 124–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Must A & Strauss RS (1999) Risks and consequences of childhood and adolescent obesity. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2, S2–S11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Freedman DS, Khan LK, Serdula MK et al. (2005) The relation of childhood BMI to adult adiposity: the Bogalusa Heart Study. Pediatrics 115, 22–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Biro FM & Wien M (2010) Childhood obesity and adult morbidities. Am J Clin Nutr 91, 1499S–1505S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. World Health Organization (WHO) (2014) Noncommunicable Diseases Country Profiles 2014. Geneva: WHO; available at http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/128038/1/9789241507509_eng.pdf?ua=1 (accessed January 2021). [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dobbs R, McKinsey Global Institute (2014) Overcoming Obesity: An Initial Economic Analysis. McKinsey Global Institute; available at https://www.noo.org.uk/news.php?nid=2733 (accessed January 2021).

- 7. Swinburn BA, Sacks G, Hall KD et al. (2011) The global obesity pandemic: shaped by global drivers and local environments. Lancet 378, 804–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wang Y, Beydoun MA, Liang L et al. (2008) Will all Americans become overweight or obese? Estimating the progression and cost of the US obesity epidemic. Obesity (Silver Spring) 16, 2323–2330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. World Health Organization (WHO) (2014) Commission on Ending Childhood Obesity: Facts and Figures on Childhood Obesity. Geneve: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE) (2015) Pesquisa de Orçamentos Familiares 2008–2009 (Family Budget Survey 2008–2009). Rio de Janeiro: POF, 127 p.

- 11. Bloch KV, Klein CH, Szklo M et al. (2016) ERICA: prevalences of hypertension and obesity in Brazilian adolescents. Rev Saude Publica 1, 9s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Maria Aiello A, Marques de Mello L, Souza Nunes M et al. (2015) Prevalence of obesity in children and adolescents in Brazil: a meta-analysis of cross-sectional studies. Curr Pediatr Rev 11, 36–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J et al. (2009) The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ 339, b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M et al. (2015) Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev 4, 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M et al. (2008) The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol 61, 344–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hoy D, Brooks P, Woolf A et al. (2012) Assessing risk of bias in prevalence studies: modification of an existing tool and evidence of interrater agreement. J Clin Epidemiol 65, 934–939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Barendregt JJ, Doi SA, Lee YY et al. (2013) Meta-analysis of prevalence. J Epidemiol Community Health 67, 974–978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Lawman HG et al. (2016) Trends in obesity prevalence among children and adolescents in the United States, 1988–1994 through 2013–2014. JAMA 315, 2292–2299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wang Y & Lobstein T (2006) Worldwide trends in childhood overweight and obesity. Int J Pediatr Obes 1, 11–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wong MCS, Huang J, Wang J et al. (2020) Global, regional and time-trend prevalence of central obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 13.2 million subjects. Eur J Epidemiol 35, 673–683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Monteiro CA, Benicio MH, Konno SC et al. (2009) Causes for the decline in child under-nutrition in Brazil, 1996–2007. Rev Saude Publica 43, 35–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Schaan CW, Cureau FV, Bloch KV et al. (2018) Prevalence and correlates of screen time among Brazilian adolescents: findings from a country-wide survey. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 43, 684–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Souza AdM, Barufaldi LA, Abreu GdA et al. (2016) ERICA: intake of macro and micronutrients of Brazilian adolescents. Revista de Saúde Pública 50, Suppl. 1, 5s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Conde WL & Monteiro CA (2014) Nutrition transition and double burden of undernutrition and excess of weight in Brazil. Am J Clin Nutr 100, 1617S–1622S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yu Z, Han S, Chu J et al. (2012) Trends in overweight and obesity among children and adolescents in China from 1981 to 2010: a meta-analysis. PLoS One 7, e51949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Conde WL & Monteiro CA (2006) Body mass index cutoff points for evaluation of nutritional status in Brazilian children and adolescent. J Pediatr (Rio J) 82, 266–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Must A, Dallal GE, Dietz WH (1991) Reference data for obesity: 85th and 95th percentiles of body mass index (wt/ht2) and triceps skinfold thickness. Am J Clin Nutr 53, 839–846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. de Onis M, Onyango AW, Borghi E et al. (2007) Development of a WHO growth reference for school-aged children and adolescents. Bull World Health Organ 85, 660–667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cole TJ, Bellizzi MC, Flegal KM et al. (2000) Establishing a standard definition for child overweight and obesity worldwide: international survey. BMJ 320, 1240–1243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. McLaren L (2007) Socioeconomic status and obesity. Epidemiol Rev 29, 29–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Batista Filho M & Rissin A (2003) Nutritional transition in Brazil: geographic and temporal trends. Cad Saude Publica 1, S181–S191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. de Alves MA, de Souza AM, Barufaldi LA et al. (2019) Dietary patterns of Brazilian adolescents according to geographic region: an analysis of the Study of Cardiovascular Risk in Adolescents (ERICA). Cadernos de Saúde Pública 35, e00153818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bloch KV, Klein CH, Szklo M et al. (2016) ERICA: prevalences of hypertension and obesity in Brazilian adolescents. Revista de Saúde Pública 50, Suppl. 1, 9s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. de Oliveira PM, da Silva FA, Oliveira RMS et al. (2016) Association between fat mass index and fat-free mass index values and cardiovascular risk in adolescents. Revista Paulista de Pediatria (English Edition) 34, 30–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Dias PC, Henriques P, Anjos LAD et al. (2017) Obesity and public policies: the Brazilian government’s definitions and strategies. Cad Saude Publica 33, e00006016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Uchimura LYT, Felisberto E, Fusaro ER et al. (2017) Evaluation performance in health regions in Brazil. Revista Brasileira de Saúde Materno Infantil. 17, S259–S270. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Werneck AO, Oyeyemi AL, Fernandes RA et al. (2018) Regional socioeconomic inequalities in physical activity and sedentary behavior among Brazilian adolescents. J Phys Act Health 15, 338–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. da Veiga GV, da Cunha AS & Sichieri R (2004) Trends in overweight among adolescents living in the poorest and richest regions of Brazil. Am J Public Health 94, 1544–1548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. de Vasconcelos Chaves VL, Freese E, Lapa TM et al. (2010) Temporal evolution of overweight and obesity among Brazilian male adolescents, 1980–2005. Cad Saude Publica 26, 1303–1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sawaya AL, Dallal G, Solymos G et al. (1995) Obesity and malnutrition in a Shantytown population in the city of Sao Paulo, Brazil. Obes Res 2, 107s–115s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Caliman SB, Castro Franceschini Sdo C & Priore SE (2006) Secular trends in growth in male adolescents: height and weight gains, nutritional state and relation with education. Arch Latinoam Nutr 56, 321–328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Chiara V, Sichieri R & Martins P (2003) Sensitivity and specificity of overweight classification of adolescents, Brazil. Rev Saude Publica 37, 226–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Peres KG, Barros AJ, Anselmi L et al. (2008) Does malocclusion influence the adolescent’s satisfaction with appearance? A cross-sectional study nested in a Brazilian birth cohort. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 36, 137–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. da Silva RCR & Malina RM (2003) Overweight, physical activity and TV viewing time among adolescents from in Niterói, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Rev Bras Ciênc Mov 11, 63–66. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Anjos LA, Castro IR, Engstrom EM et al. (1999) Growth and nutritional status in a probabilistic sample of schoolchildren from Rio de Janeiro. Cad Saude Publica 19, S171–S179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Lancarotte I, Nobre MR, Zanetta R et al. (2010) Lifestyle and cardiovascular health in school adolescents from Sao Paulo. Arq Bras Cardiol 95, 61–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Frainer DES, da Silva MdCM, Santana MLPd et al. (2011) Prevalence and associated factors of surplus weight in adolescents from Salvador, Bahia, Brazil. Revista Brasileira de Medicina do Esporte 17, 102–106. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Freitas Júnior IF, Balikian Júnior P, Miyashita LK et al. (2008) Growth and nutritional status of children and adolescents in the city of Presidente Prudente, State of São Paulo, Brazil. Revista Brasileira de Saúde Materno Infantil 8, 265–274. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Nobre MR, Domingues RZ, da Silva AR et al. (2006) Prevalence of overweight, obesity and life style associated with cardiovascular risk among middle school students. Rev Assoc Med Bras (1992) 52, 118–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Farias Júnior JCd & Lopes AdS (2003) Prevalence of overweight in adolescents. Rev Bras Ciênc Mov 11, 77–84. [Google Scholar]

- 51. de Souza Ferreira JE & da Veiga GV (2008) Eating disorder risk behavior in Brazilian adolescents from low socio-economic level. Appetite 51, 249–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Terres NG, Pinheiro RT, Horta BL et al. (2006) Prevalence and factors associated to overweight and obesity in adolescents. Rev Saude Publica 40, 627–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Campagnolo PD, Vitolo MR, Gama CM et al. (2008) Prevalence of overweight and associated factors in southern Brazilian adolescents. Public Health 122, 509–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Del Duca GF, Garcia LMT, de Sousa TF et al. (2010) Body weight dissatisfaction and associated factors among adolescents. Revista Paulista de Pediatria 28, 340–346. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Kuschnir FC & da Cunha AL (2009) Association of overweight with asthma prevalence in adolescents in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. J Asthma 46, 928–932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Rodrigues AN, Moyses MR, Bissoli NS et al. (2006) Cardiovascular risk factors in a population of Brazilian schoolchildren. Braz J Med Biol Res 39, 1637–1642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Amorim PR, de Faria RC, Byrne NM et al. (2006) Physical activity and nutritional status of children of low socioeconomic status. Two interrelated problems: undernutrition and overweight. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr 15, 217–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Barros EG, Pereira RA, Sichieri R et al. (2014) Variation of BMI and anthropometric indicators of abdominal obesity in Brazilian adolescents from public schools, 2003–2008. Public Health Nutr 17, 345–352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Campos LDA, Leite ÁJM, De Almeida PC. (2006) Socioeconomic status and its influence on the prevalence of overweight and obesity among adolescent school children in the city of Fortaleza, Brazil. Revista de Nutricao 19, 531–538. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Costa MCD, Cordoni Junior L & Matsuo T (2007) Overweight in adolescents aged 14 to 19 years old in a Southern Brazilian city. Revista Brasileira de Saúde Materno Infantil 7, 263–270. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Dutra CL, Araujo CL & Bertoldi AD (2006) Prevalence of overweight in adolescents: a population-based study in a southern Brazilian city. Cad Saude Publica 22, 151–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Gomes FdS, Anjos LAd, Vasconcellos MTLd (2009) Influence of different body mass index cut-off values in assessing the nutritional status of adolescents in a household survey. Cadernos de Saúde Pública 25, 1850–1857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Rosa ML, Fonseca VM, Oigman G et al. (2006) Arterial prehypertension and elevated pulse pressure in adolescents: prevalence and associated factors. Arq Bras Cardiol 87, 46–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Pereira JL, Félix PV, Mattei J et al. (2018) Differences over 12 years in food portion size and association with excess body weight in the city of São Paulo, Brazil. Nutrients 10, 696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Pelegrini A, Silva DAS, Petroski EL et al. (2010) Nutritional status and associated factors in schoolchildren living in rural and urban areas. Revista de Nutrição 23, 839–846. [Google Scholar]

- 66. Araujo CL, Dumith SC, Menezes AM et al. (2010) Nutritional status of adolescents: the 11-year follow-up of the 1993 Pelotas (Brazil) birth cohort study. Cad Saude Publica 26, 1895–1903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Barbiero SM, Pellanda LC, Cesa CC et al. (2009) Overweight, obesity and other risk factors for IHD in Brazilian schoolchildren. Public Health Nutr 12, 710–715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Cintra IdP, Zanetti Passos MA, Dos Santos LC et al. (2014) Waist-to-height ratio percentiles and cutoffs for obesity: a cross-sectional study in Brazilian adolescents. J Health Popul Nutr 32, 411–419. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Detsch C, Luz AMH, Candotti CT et al. (2007) Prevalence of postural changes in high school students in a city in southern Brazil. Revista Panamericana de Salud Pública 21, 231–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Thomaz EB, Cangussu MC, da Silva AA et al. (2010) Is malnutrition associated with crowding in permanent dentition? Int J Environ Res Public Health 7, 3531–3544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Suñé FR, Dias-Da-Costa JS, Olinto MTA et al. (2007) Prevalence of overweight and obesity and associated factors among schoolchildren in a southern Brazilian city. Cadernos de Saude Publica 23, 1361–1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Goldani MZ, Barbieri MA, da Silva AA et al. (2013) Cesarean section and increased body mass index in school children: two cohort studies from distinct socioeconomic background areas in Brazil. Nutr J 12, 104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Toral N, Slater B & da Silva MV (2007) Food consumption and overweight in adolescents from Piracicaba, São Paulo, Brazil. Rev Nutr 20, 449–459. [Google Scholar]

- 74. Aerts D, Madeira RR & Zart VB (2010) Body image of teenage students from Gravatai, State of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. Epidemiol Serv Saúde 19, 283–291. [Google Scholar]

- 75. Vanzelli AS, Castro CTd, Pinto MdS et al. (2008) Prevalence of overweight and obesity among children of public schools in the city of Jundiaí, São Paulo, Brazil. Revista Paulista de Pediatria 26, 48–53. [Google Scholar]

- 76. Santana DD, Barros EG, Costa RSD et al. (2017) Temporal changes in the prevalence of disordered eating behaviors among adolescents living in the metropolitan area of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Psychiatry Res 253, 64–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Fanhani KK & Bennemann RM (2011) Nutrition status of municipal schoolchildren in Maringá, Paraná State, Brazil. Acta Scientiarum – Health Sci 33, 77–82. [Google Scholar]

- 78. Flores LS, Gaya AR, Petersen RD et al. (2013) Trends of underweight, overweight, and obesity in Brazilian children and adolescents. J Pediatr (Rio J) 89, 456–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Oliveira JS, de Lira PIC, Veras ICL et al. (2009) Nutritional status and food insecurity of adolescents and adults in two cities with a low human development index. Rev Nutr 22, 453–465. [Google Scholar]

- 80. Silva KS & Lopes AS (2008) Excess weight, arterial pressure and physical activity in commuting to school: correlations. Arq Bras Cardiol 91, 84–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Stabelini Neto A, Bozza R, Ulbrich A et al. (2012) Metabolic syndrome in adolescents of different nutritional status. Arq Bras Endocrinol Metabol 56, 104–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Coelho LG, Candido AP, Machado-Coelho GL et al. (2012) Association between nutritional status, food habits and physical activity level in schoolchildren. J Pediatr (Rio J) 88, 406–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Fernandes RA, Rosa CS, Silva CB et al. (2007) Accuracy of different body mass index cutoffs to predict excessive body fat and abdominal obesity in adolescents. Rev Assoc Med Bras (1992) 53, 515–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Kac G, Velasquez-Melendez G, Schlussel MM et al. (2012) Severe food insecurity is associated with obesity among Brazilian adolescent females. Public Health Nutr 15, 1854–1860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Leal VS, de Lira PIC, Oliveira JS et al. (2012) Overweight in children and adolescents in Pernambuco state, Brazil: prevalence and determinants. Cadernos de Saude Publica 28, 1175–1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Tassitano RM, de Barros MVG, Tenório MCM et al. (2009) Prevalence of overweight and obesity and associated factors among public high school students in Pernambuco State, Brazil. Cadernos de Saúde Pública 25, 2639–2652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Pelegrini A & Petroski EL (2007) Overweight Adolescents: Prevalence And Related Factors. Rev bras ativ fís saúde. 12, 45–53. [Google Scholar]

- 88. Benedet J, de Assis MAA, Calvo MCM et al. (2013) Overweight in adolescents: exploring potential risk factors. Revista Paulista de Pediatria 31, 172–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Christofaro DG, Fernandes RA, Oliveira AR et al. (2014) The association between cardiovascular risk factors and high blood pressure in adolescents: a school-based study. Am J Hum Biol 26, 518–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. da Silva JB, da Silva FG, de Medeiros HJ et al. (2009) The nutritional status of schoolchildren living in the semi-arid area of northern Brazil. Rev Salud Publica (Bogota) 11, 62–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Silva A & Hasselmann MH (2018) Association between domestic maltreatment and excess weight and fat among students of the city/state of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Cien Saude Colet 23, 4129–4142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Fernandes RA, Conterato I, Messias KP et al. (2009) Risk factors associated with overweight among adolescents from western Sao Paulo state. Rev Esc Enferm USP 43, 768–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Guedes DP, Rocha GD, Silva AJ et al. (2011) Effects of social and environmental determinants on overweight and obesity among Brazilian schoolchildren from a developing region. Rev Panam Salud Publica 30, 295–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Guerra LD, Espinosa MM, Bezerra AC et al. (2013) Food insecurity in households with adolescents in the Brazilian Amazon: prevalence and associated factors. Cad Saude Publica 29, 335–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Pinto ICS, de Arruda IKG, Diniz AS et al. (2010) Prevalence of overweight and abdominal obesity according to anthropometric parameters and the association with sexual maturation in adolescent schoolchildren. Cadernos de Saude Publica 26, 1727–1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Laus MF, Miranda VP, Almeida SS et al. (2013) Geographic location, sex and nutritional status play an important role in body image concerns among Brazilian adolescents. J Health Psychol 18, 332–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Vieira Cunha Lima SC, Oliveira Lyra C, Galvao Bacurau Pinheiro L et al. (2011) Association between dyslipidemia and anthropometric indicators in adolescents. Nutr Hosp 26, 304–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Caran LG, Santana DD, Monteiro LS et al. (2018) Disordered eating behaviors and energy and nutrient intake in a regional sample of Brazilian adolescents from public schools. Eat Weight Disord 23, 825–832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Bispo S, Correia MI, Proietti FA et al. (2015) Nutritional status of urban adolescents: individual, household and neighborhood factors based on data from The BH Health Study. Cad Saude Publica 1, 232–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. de Souza CO, de Silva RCR, Assis AMO et al. (2010) Association between physical inactivity and overweight among adolescents in Salvador, Bahia – Brazil. Rev Bras Epidemiol 13, 468–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Castro TG, Barufaldi LA, Schlussel MM et al. (2012) Waist circumference and waist circumference to height ratios of Kaingang indigenous adolescents from the State of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. Cad Saude Publica 28, 2053–2062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Cunha DB, Bezerra IN, Pereira RA et al. (2018) At-home and away-from-home dietary patterns and BMI z-scores in Brazilian adolescents. Appetite 120, 374–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Cureau FV, Duarte PM, dos Santos DL et al. (2012) Overweight/obesity in adolescents from Santa Maria, Brazil: prevalence and associated factors. Rev Bras Cineantropom Desempenho Hum 14, 517–526. [Google Scholar]

- 104. de Moraes AC, Musso C, Graffigna MN et al. (2014) Prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors among Latin American adolescents: a multilevel analysis. J Hum Hypertens 28, 206–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Silva DAS, Pelegrini A, Grigollo LR et al. (2011) Differences and similarities in stages of behavioral change related to physical activity in adolescents from two regions of Brazil. Revista Paulista de Pediatria 29, 193–201. [Google Scholar]

- 106. Silva DA, de Lima LR, Dellagrana RA et al. (2013) High blood pressure in adolescents: prevalence and associated factors. Cien Saude Colet 18, 3391–3400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Polderman J, Gurgel RQ, Barreto-Filho JA et al. (2011) Blood pressure and BMI in adolescents in Aracaju, Brazil. Public Health Nutr 14, 1064–1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Krinski K, Elsangedy HM, da Hora S et al. (2011) Nutritional status and association of overweight with gender and age in children and adolescents. Rev Bras Cineantropom Desempenho Hum 13, 29–35. [Google Scholar]

- 109. da Silva BB, de Menezes MC, Nunes KS et al. (2019) Association between body mass index and asthma symptoms among teenage students in São José, Santa Catarina, Brazil. ACM Arq Catarin Med 48, 71–81. [Google Scholar]

- 110. de Fiuza RFP, Muraro AP, Rodrigues PRM et al. (2017) Skipping breakfast and associated factors among Brazilian adolescents. Revista de Nutrição 30, 615–626. [Google Scholar]

- 111. Romero A, Borges C & Slater B (2015) Patterns of physical activity and sedentary behavior associated with overweight in Brazilian adolescents. Rev Bras Ativ Fís Saúde 20, 26–35. [Google Scholar]

- 112. Araujo C, Toral N, Silva AC et al. (2010) Nutritional status of adolescents and its relation with socio-demographics variables: national Adolescent School-based Health Survey (PeNSE), 2009. Cien Saude Colet 2, 3077–3084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. dos Farias ES, dos Santos AP, de Farias-Júnior JC et al. (2012) Excess weight and associated factors in adolescents. Revista de Nutrição 25, 229–236. [Google Scholar]

- 114. Santana ML, de Silva RC, Assis AM et al. (2013) Factors associated with body image dissatisfaction among adolescents in public schools students in Salvador, Brazil. Nutr Hosp 28, 747–755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Miranda VP, Conti MA, de Carvalho PH et al. (2014) Body image in different periods of adolescence. Rev Paul Pediatr 32, 63–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Leal G, Philippi ST & Alvarenga MDS (2020) Unhealthy weight control behaviors, disordered eating, and body image dissatisfaction in adolescents from São Paulo, Brazil. Braz. J Psychiatry 42, 264–270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Lock NC, Susin C, Damé-Teixeira N et al. (2020) Sex differences in the association between obesity and gingivitis among 12-year-old South Brazilian schoolchildren. J Periodontal Res 55, 559–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Neto AC, de Andrade MI, de Menezes Lima VL et al. (2015) Body weight and food consumption scores in adolescents from northeast Brazil. Rev Paul Pediatr 33, 319–326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Castilho SD, Nucci LB, Hansen LO et al. (2014) Prevalence of weight excess according to age group in students from Campinas, SP, Brazil. Rev Paul Pediatr 32, 200–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Cecon RS, Franceschini SDCC, Peluzio MDCG et al. (2017) Overweight and body image perception in adolescents with triage of eating disorders. Sci World J 2017 2017, 8257329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Raphaelli CO, Azevedo MR & Hallal PC (2011) Association between health risk behaviors in parents and adolescents in a rural area in southern Brazil. Cadernos de Saude Publica 27, 2429–2440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. da Cruz LL, Cardoso LD, Pala D et al. (2013) Metabolic syndrome components can predict C reactive protein concentration in adolescents. Nutr Hosp 28, 1580–1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Souza LS, Santo RCE, Franceschi C et al. (2017) Anthropometric nutritional status and association with blood pressure in children and adolescents: a population-based study. Sci Med 27, ID25592. [Google Scholar]

- 124. Vasconcellos MB, Anjos LA & Vasconcellos MT (2013) Nutritional status and screen time among public school students in Niteroi, Rio de Janeiro State, Brazil. Cad Saude Publica 29, 713–722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. de Moraes MM, Moreira NF, de Oliveira ASD et al. (2019) Associations of changes in BMI and body fat percentage with demographic and socioeconomic factors: the ELANA middle school cohort. Int J Obes (Lond) 43, 2282–2290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Franceschin MJ & da Veiga GV (2020) Association of cardiorespiratory fitness, physical activity level, and sedentary behavior with overweight in adolescents. Revista Brasileira de Cineantropometria Desempenho Humano 22, e60449. [Google Scholar]

- 127. Monteiro AR, Dumith SC, Goncalves TS et al. (2016) Overweight among young people in a city in the Brazilian semiarid region: a population-based study. Cien Saude Colet 21, 1157–1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.de Carneiro CS, do Peixoto MRG, Mendonça KL et al. (2017) Overweight and associated factors in adolescents from a brazilian capital. Revista Brasileira de Epidemiologia 20, 260–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Christofaro D, Andrade SM, Fernandes RA et al. (2016) Overweight parents are twice as likely to underestimate the weight of their teenage children, regardless of their sociodemographic characteristics. Acta Paediatr 105, e474–e479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Coutinho CA, Longui CA, Monte O et al. (2014) Measurement of neck circumference and its correlation with body composition in a sample of students in Sao Paulo, Brazil. Horm Res Paediatr 82, 179–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Cureau FV, Duarte P, dos Santos DL et al. (2014) Clustering of risk factors for noncommunicable diseases in Brazilian adolescents: prevalence and correlates. J Phys Act Health 11, 942–949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132. Guedes DP, Miranda Neto JT, de Silva MMD (2014) Anthropometric nutritional of adolescents from a region of low economic development in Brazil: comparison with the WHO-2007 reference. Rev Bras Cineantropom Desempenho Hum 16, 258–267. [Google Scholar]

- 133. de Pinho L, Botelho AC & Caldeira AP (2014) Associated factors of overweight in adolescents from public schools in Northern Minas Gerais State, Brazil. Rev Paul Pediatr 32, 237–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134. Finato S, Rech RR, Migon P et al. (2013) Body image insatisfaction in students from the sixth grade of public schools in Caxias do Sul, Southern Brazil. Rev Paul Pediatr 31, 65–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135. Fortes Lde, S , Cipriani FM & Ferreira ME (2013) Risk behaviors for eating disorder: factors associated in adolescent students. Trends Psychiatry Psychother 35, 279–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136. Graup S, de Araujo Bergmann ML & Bergmann GG (2014) Prevalence of nonspecific lumbar pain and associated factors among adolescents in Uruguaiana, state of Rio Grande do Sul. Rev Bras Ortop 49, 661–667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137. Guedes DP, Almeida FN, Neto JT et al. (2013) Low body weight/thinness, overweight and obesity of children and adolescents from a Brazilian region of low economic status. Rev Paul Pediatr 31, 437–443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138. de Sousa Júnior I, de França NM, Silva GCB et al. (2013) Relation between food habits and body mass index in students of public institutions of northeast brazilian. Pensar Prát (Impr) 16, 435–450. [Google Scholar]

- 139. Oliveira L, Ritti-Dias RM, Farah BQ et al. (2018) Does the type of sedentary behaviors influence blood pressurein adolescents boys and girls? A cross-sectional study. Cien Saude Colet 23, 2575–2585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140. Rosini N, Moura SAZO, Rosini RD et al. (2015) Metabolic syndrome and importance of associated variables in children and adolescents in Guabiruba – SC, Brazil. Arquivos Brasileiros de Cardiologia 105, 37–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141. Pitanga FJG, Alves CFA, Pamponet ML et al. (2019) Combined effect of physical activity and reduction of screen time for overweight prevention in adolescents. Revista Brasileira de Cineantropometria Desempenho Humano 21, e58392. [Google Scholar]

- 142. Anjos LAD, Silveira W (2017) Nutritional status of schoolchildren of the National Child and Youth Education Teaching Network of the Social Service of Commerce (Sesc), Brazil, 2012. Cien Saude Colet 22, 1725–1734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143. Cavalcanti AL, Ramos IA, Cardoso AM et al. (2016) Association between periodontal condition and nutritional status of Brazilian adolescents: a population-based study. Iran J Public Health 45, 1586–1594. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144. D’Avila GL, Müller RL, Gonsalez PS et al. (2015) The association between nutritional status of the mother and the frequency and location of and company during meals and overweight/obesity among adolescents in the city of Florianópolis, Brazil. Rev Bras Saúde Matern Infant 15, 289–299. [Google Scholar]

- 145. Neves FS, Leandro DA, Silva FA et al. (2015) Evaluation of the predictive capacity of vertical segmental tetrapolar bioimpedance for excess weight detection in adolescents. J Pediatr (Rio J) 91, 551–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146. Lopes VP, Malina RM, Gomez-Campos R et al. (2019) Body mass index and physical fitness in Brazilian adolescents. J Pediatr (Rio J) 95, 358–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147. de Guimarães RF, da Silva MP, Mazzardo O et al. (2013) Association between sedentary behavior, anthropometric, metabolic profiles among adolescents. Motriz: Revista de Educação Física 19, 753–762. [Google Scholar]

- 148. Iepsen AM, da Silva MC (2014) Body image dissatisfaction prevalence and associated factors among adolescents at rural high schools in the southern region of Rio Grande do Sul State, Brazil, 2012. Epidemiologia e Serviços de Saúde 23, 317–325. [Google Scholar]

- 149. Rodrigues NL, Lima LH, Carvalho Ede S et al. (2015) Risk factors for cardiovascular diseases in adolescents. Invest Educ Enferm 33, 315–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150. Almeida Santana CC, Farah BQ, de Azevedo LB et al. (2017) Associations between cardiorespiratory fitness and overweight with academic performance in 12-year-old Brazilian children. Pediatr Exerc Sci 29, 220–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151. de Aranha LAR, Lima RV, Magalhães WOG et al. (2020) Association between excess body weight and experience of dental caries in students from the municipality of Barcelos, Amazonas, Brazil: a cross-sectional study. Arq odontol 56, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 152. Costa MVC, Calderan MF & Cruvinel T (2020) Could orthodontic fixed appliances and excess weight affect gingival health in adolescents? Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 157, 172–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153. Silva DAS, Lang JJ, Petroski EL et al. (2020) Association between 9-minute walk/run test and obesity among children and adolescents: evidence for criterion-referenced cut-points. PeerJ 8, e8651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154. Vieira CENK, Enders BC, Coura AS et al. (2015) Nursing diagnosis of overweight and related factors in adolescents. Invest Educ Enferm 33, 509–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155. D’Avila HF & Kirsten VR (2017) Energy Intake From Ultra-processed Foods Among Adolescents. Revista Paulista de Pediatria 35, 54–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156. Enes CC & Silva JR (2018) Association between excess weight and serum lipid alterations in adolescents. Cien Saude Colet 23, 4055–4063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157. Paes-Silva RP, Tomiya MTO, Maio R et al. (2018) Prevalence and factors associated with fat-soluble vitamin deficiency in adolescents. Nutr Hosp 35, 1153–1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158. Guilherme FR, Molena-Fernandes CA, Guilherme VR et al. (2015) Physical inactivity and anthropometric measures in schoolchildren from Paranavaí, Paraná, Brazil. Revista Paulista de Pediatria 33, 50–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159. Alberti A, Kupek E, Comim CM et al. (2019) Dermatoglyphical impressions are different between children and adolescents with normal weight, overweight and obesity: a cross-sectional study. F1000Research 8, 964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160. da Silva AAdP, de Camargo EM, da Silva AT et al. (2019) Characterization of physical activities performed by adolescents from Curitiba, Brazil. Revista Brasileira de Medicina do Esporte 25, 211–215.

- 161. Pereira KAS, Nunes SEA, Belfort MGS et al. (2017) Risk and protective factors for noncommunicable diseases among adolescents. Rev Bras Promoç saúde (Impr) 30, 205–212. [Google Scholar]

- 162. Silva CS, da Silva Junior CT, Ferreira BS et al. (2016) Prevalence of underweight, overweight, and obesity among 2, 162 Brazilian school adolescents. Indian J Endocrinol Metab 20, 228–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163. de Araujo TS, Barbosa Filho VC, Gubert FDA et al. (2017) Factors associated with body image perception among Brazilian students from low human development index areas. J Sch Nurs. doi: 10.1177/1059840517718249. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 164. Carmo CDS, Ribeiro MRC, Teixeira JXP et al. (2018) Added sugar consumption and chronic oral disease Burden among adolescents in Brazil. J Dent Res 97, 508–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165. Fradkin C, Valentini NC, Nobre GC et al. (2018) Obesity and overweight among brazilian early adolescents: variability across region, socioeconomic status, and gender. Front Pediatr 6, 81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166. Gemelli IFB, Farias EDS & Souza OF (2016) Age at Menarche and its association with excess weight and body fat percentage in girls in the Southwestern region of the Brazilian Amazon. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 29, 482–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167. Pozza FS, Nucci LB & Enes CC (2018) Identifying overweight and obesity in Brazilian schoolchildren, 2014. J Public Health Manag Pract 24, 204–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168. Reuter CP, Burgos MS, Barbian CD et al. (2018) Comparison between different criteria for metabolic syndrome in schoolchildren from southern Brazil. Eur J Pediatr 177, 1471–1477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169. Silva DAS, Martins PC, de Gonçalves ECA (2018) Comparison of three criteria for overweight and obesity classification among adolescents from southern Brazil. Motriz: Rev Educ Fis 23, e1017118. [Google Scholar]

- 170. Ulbricht L, de Campos MF, Esmanhoto E et al. (2018) Prevalence of excessive body fat among adolescents of a south Brazilian metropolitan region and State capital, associated risk factors, and consequences. BMC Public Health 18, 312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 171. Guimarães MR, dos Santos AA, de Moura TFR et al. (2019) Clinical and metabolic alterations and insulin resistance among adolescents. Acta Paulista de Enfermagem 32, 608–616. [Google Scholar]

- 172. Moura IRD, Barbosa AO, Silva ICM et al. (2019) Impact of cutoff points on adolescent sedentary behavior measured by accelerometer. Rev Bras Ativ Fís Saúde 24, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 173. Marques AyC, Braga IEM, de Oliveira de EDA et al. (2016) Intake of high-sodium foods and change of pressure levels in adolescents living in Itaqui/RS, Brazil. Rev AMRIGS 60, 97–103. [Google Scholar]

- 174. Ripka WL, Ulbricht L & Gewehr PM (2017) Body composition and prediction equations using skinfold thickness for body fat percentage in Southern Brazilian adolescents. PLoS One 12, e0184854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 175. Da Silva AF, Martins PC, de Gonçalves ECA et al. (2018) Prevalence and factors associated with sedentary behavior in the school recess among adolescents. Motriz: Rev Educ Fis 24, e101834. [Google Scholar]

- 176. Lourenço CLM, Zanetti HR, Amorim PRS et al. (2018) Sedentary behavior in adolescents: prevalence and associated factors. R Bras CI e Mov 26: 23–32. [Google Scholar]

- 177. Tebar WR, Ritti-Dias RM, Farah BQ et al. (2018) High blood pressure and its relationship to adiposity in a school-aged population: body mass index vs waist circumference. Hypertens Res 41, 135–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 178. da Silva SU, Barufaldi LA, de Andrade SSCA et al. (2018) Nutritional status, body image, and their association with extreme weight control behaviors among Brazilian adolescents, National Adolescent Student Health Survey 2015. Revista Brasileira de Epidemiologia 21, e180011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 179. Farias EDS, Carvalho WRG, Moraes AM et al. (2019) Inactive behavior in adolescent students of the Brazilian western amazon. Rev Paul Pediatr 37, 345–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 180. Guttier MC, Barcelos RS, Ferreira RW et al. (2019) Repeated high blood pressure at 6 and 11 years at the Pelotas 2004 birth cohort study. BMC Public Health 19, 1260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 181. Ramos DE, de Bueno MRO, Vignadelli LZ et al. (2019) Pattern of sedentary behavior in Brazilian adolescents. Rev Bras Ativ Fís Saúde 23, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 182. da Silva MP, Pacífico AB, Piola TS et al. (2020) Association between physical activity practice and clustering of health risk behaviors in adolescents. Revista Paulista de Pediatria 38, e2018247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 183. Cesar JT, Taconeli CA, Osório MM et al. (2020) Adherence to school food and associated factors among adolescents in public schools in the Southern region of Brazil. Ciência Saúde Coletiva 25, 977–988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 184. Schwertner DS, Oliveira R, Koerich M et al. (2020) Prevalence of low back pain in young Brazilians and associated factors: sex, physical activity, sedentary behavior, sleep and body mass index. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil 33, 233–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 185. de Souza Dantas M, Dos Santos MC, Lopes LAF et al. (2018) Clustering of excess body weight-related behaviors in a sample of Brazilian adolescents. Nutrients 10, 1505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 186. Lima RA, de Barros MVG, Dos Santos MAM et al. (2020) The synergic relationship between social anxiety, depressive symptoms, poor sleep quality and body fatness in adolescents. J Affect Disord 260, 200–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980021001464.

click here to view supplementary material