Key Points

Question

How frequently are patient-reported outcomes (PROs) used as end points in randomized clinical trials (RCTs) of hematological malignant neoplasms, and are these PROs reported in primary trial publications?

Findings

In this systematic review of 90 therapeutic RCTs of hematological malignant neoplasms, 66 included PROs as an end point, but only 1 as a primary end point. PRO data were reported in 26 of the 66 publications: PROs were unchanged in 18 studies and improved in 8, with none reporting worse PROs with experimental treatment.

Meaning

These results suggest there is widespread collection of PROs for blood cancer trials but limited reporting of PRO data in associated primary trial publications, raising concerns for publication bias.

This systematic review of randomized clinical trials investigating hematological malignant neoplasms examines how often patient-reported outcomes are included in results.

Abstract

Importance

Published research suggests that patient-reported outcomes (PROs) are neither commonly collected nor reported in randomized clinical trials (RCTs) for solid tumors. Little is known about these practices in RCTs for hematological malignant neoplasms.

Objective

To evaluate the prevalence of PROs as prespecified end points in RCTs of hematological malignant neoplasms, and to assess reporting of PROs in associated trial publications.

Evidence Review

All issues of 8 journals known for publishing high-impact RCTs (NEJM, Lancet, Lancet Hematology, Lancet Oncology, Journal of Clinical Oncology, Blood, JAMA, and JAMA Oncology) between January 1, 2018, and December 13, 2022, were searched for primary publications of therapeutic phase 3 trials for adults with hematological malignant neoplasms. Studies that evaluated pretransplant conditioning regimens, graft-vs-host disease treatment, or radiotherapy as experimental treatment were excluded. Data regarding trial characteristics and PROs were extracted from manuscripts and trial protocols. Univariable analyses assessed associations between trial characteristics and PRO collection or reporting.

Findings

Ninety RCTs were eligible for analysis. PROs were an end point in 66 (73%) trials: in 1 trial (1%) as a primary end point, in 50 (56%) as a secondary end point, and in 15 (17%) as an exploratory end point. PRO data were reported in 26 of 66 primary publications (39%): outcomes were unchanged in 18 and improved in 8, with none reporting worse PROs with experimental treatment. Trials sponsored by for-profit entities were more likely to include PROs as an end point (49 of 55 [89%] vs 17 of 35 [49%]; P < .001) but were not significantly more likely to report PRO data (20 of 49 [41%] vs 6 of 17 [35%]; P = .69). Compared with trials involving lymphoma (18 of 29 [62%]) or leukemia or myelodysplastic syndrome (18 of 28 [64%]), those involving plasma cell disorders or multiple myeloma (27 of 30 [90%]) or myeloproliferative neoplasms (3 of 3 [100%]) were more likely to include PROs as an end point (P = .03). Similarly, compared with trials involving lymphoma (3 of 18 [17%]) or leukemia or myelodysplastic syndrome (5 of 18 [28%]), those involving plasma cell disorders or multiple myeloma (16 of 27 [59%]) or myeloproliferative neoplasms (2 of 3 [67%]) were more likely to report PROs in the primary publication (P = .01).

Conclusions and Relevance

In this systematic review, almost 3 of every 4 therapeutic RCTs for blood cancers collected PRO data; however, only 1 RCT included PROs as a primary end point. Moreover, most did not report resulting PRO data in the primary publication and when reported, PROs were either better or unchanged, raising concern for publication bias. This analysis suggests a critical gap in dissemination of data on the lived experiences of patients enrolled in RCTs for hematological malignant neoplasms.

Introduction

There is growing interest in incorporating patient-reported outcomes (PROs) into clinical trials as a way to better capture health-related quality of life (HRQOL) and other patient-centered end points beyond survival.1,2 PROs are the criterion standard for the assessment of subjective symptoms, as patients are in the best position to comment on their own lived experience of treatment. Indeed, several studies have shown that physicians routinely underestimate the incidence and severity of patients’ symptoms,3,4,5,6,7,8,9 and that PROs are more often concordant with overall health status than physician-led toxicity reports.10 Both the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) and the European Society of Medical Oncology (ESMO) include PRO data among the parameters considered for evaluation of clinical value of cancer-related drugs, with additional points conferred to drugs that can reliably demonstrate improvement in HRQOL and other PROs.11,12

The use of PROs as end points in randomized clinical trials (RCTs) is widely variable in oncology, and the collection and reporting of PRO data has been considered to be suboptimal.13,14,15 For example, a systematic review by Marandino and colleagues14 found that among phase 3 trials for solid tumors published between 2012 and 2016, HRQOL was not an end point in 47% of the trials, and related data were commonly underreported in the associated primary trial publications. Moreover, prior studies have suggested that even when clinical trials do collect PROs, they are infrequently assessed after disease progression and rarely followed until the end of a patient’s life.16

In contrast, there are sparse data about the use of PROs in RCTs for hematological malignant neoplasms. Given the significant morbidity associated with many blood cancers as well as the adoption of prolonged, non–fixed duration treatment in multiple hematological malignant neoplasms, PROs are critical to evaluate the effectiveness of drugs in this patient population. A prior study17 suggested that PROs were infrequently measured for pivotal blood cancer drugs that received FDA approval between January 2016 and May 2020. While an important contribution, a better denominator is all trials that were published in high-impact journals, given that not all trials lead to FDA approval. Moreover, key features of PRO data, such as the timing of data collection and associations of PRO collection and reporting with trial characteristics, have not been described. In this context, we hypothesized that PROs would be collected in a minority of therapeutic RCTs for blood cancers, and that only a subset of these trials would report PRO data in their primary publication.

Methods

Reporting, Information Sources, and Search Strategy

The present study followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) reporting guidelines. This study was exempt from institutional review board review because it involved the collection or study of existing, deidentified data.

The following 8 journals were selected by study team consensus for review because of their history of publishing high-impact blood cancer RCTs: New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM), Lancet, Lancet Hematology, Lancet Oncology, Journal of Clinical Oncology, Blood, JAMA, and JAMA Oncology. Journal issues published between January 1, 2018, and December 13, 2022, were manually searched for primary publications of therapeutic phase 3 trials for adults with hematological malignant neoplasms. For trials published in 2018 and 2019, secondary peer-reviewed publications reporting PROs were subsequently identified using an advanced PubMed search (run on March 22, 2023) with the terms (trial name) AND ((disease) OR (drug)) AND ((quality of life) OR (patient reported outcome) OR (PRO) OR (QOL) OR (HRQOL)), and secondary abstracts reporting PROs at the American Society of Hematology (ASH) and European Hematology Association (EHA) annual meetings were identified using a search (run on March 7, 2024) with the terms (trial name) AND ((quality of life) OR (PRO)) in the respective abstract libraries. The 2018-2019 years were selected to maximize the probability of a secondary publication specific to PROs. The quality of the data sources was based on the Oxford Center for Evidence-Based Medicine’s Levels of Evidence and Grades of Recommendation; since all the included studies were phase 3 RCTs, all had a rating of 1.18

Eligibility Criteria

Eligible trials were therapeutic, phase 3 RCTs that included adult patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML), acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL), acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML), hairy cell leukemia, Hodgkin lymphoma, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, multiple myeloma, Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia, light-chain amyloidosis, myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), and myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) including polycythemia vera, essential thrombocythemia, and primary myelofibrosis. Studies that evaluated immunosuppressive regimens for graft-vs-host disease (GVHD), conditioning regimens prior to hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, or radiotherapy as experimental treatment were excluded. Studies for which the original trial protocol document was not available were also excluded.

Data Extraction

Two investigators (K.P. and A.I.) independently extracted data from each eligible clinical trial protocol and publication; discrepancies were resolved by consensus arbitration with a third investigator (G.A.). Concordance was assessed by calculation of κ statistics for major extracted variables. For each study, extracted data included: journal of publication, date of publication, type of malignant neoplasm, disease stage (first-line treatment, relapsed or refractory treatment, or maintenance treatment after remission or transplantation), number of study arms, single or multinational study, primary sponsor (pharmaceutical company, hospital or academic institution, or trial or cooperative group, as listed on ClinicalTrials.gov), type of experimental treatment (chemotherapy, targeted therapy or immunotherapy, cellular therapy, growth factor or erythroid maturation agent, or transplantation), duration of therapy (time-limited or indefinite), masking (double-masked or open label), primary end point, and study design (superiority or noninferiority). Studies were labeled as positive (when 1 or more primary end points were met) or negative. Trials were considered for-profit when sponsored by a pharmaceutical company and as nonprofit when sponsored by a hospital, academic institution, or cooperative group.

Information regarding PROs was collected from the primary trial publication as well as the trial protocol. The publication through which the trial was included in the analysis was considered the primary trial publication. Extracted information included: incorporation of PROs as an end point (primary, secondary, exploratory); the instruments used to collect PRO data (eg, European Organization for Research and Treatment Quality of Life of Cancer Patients [EORTC-QLQ-C30], EuroQol Research Foundation 5 Dimensions [EQ-5D], Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General [FACT-G]); the timing of PRO measurement (ie, during treatment, at the end-of-treatment visit, and/or after the end-of-treatment visit); whether the PRO data were reported in the primary trial publication or data supplement; and the reported effect of the experimental treatment on PROs (ie, improved, no change, or worse). For the timing of PRO measurement, trials were characterized as having collected PRO data after the end-of-treatment visit only if PRO data were collected more than 1 month afterward, with the intention to screen out trials where the only additional PRO datapoint was at a single safety follow-up visit within one month of the end-of-treatment.

Secondary publications and ASH or EHA abstracts reporting PROs were identified for clinical trials published in 2018 and 2019 where PROs were included as an end point but PRO data had not been reported in the primary publication. These years were selected to allow for sufficient time for a secondary analysis dedicated to PROs to be published. Delays in publication time between primary and secondary publications were calculated in months.

Statistical Analysis

Associations between trial characteristics and the collection and reporting of PROs in the primary publication were assessed using χ2 or Fisher exact test. Significance was considered at P < .05 and analyses were 2-tailed; there was no adjustment for multiple comparisons. Statistical analysis was performed using Stata version 17 (StataCorp).

Results

Study Selection and Concordance

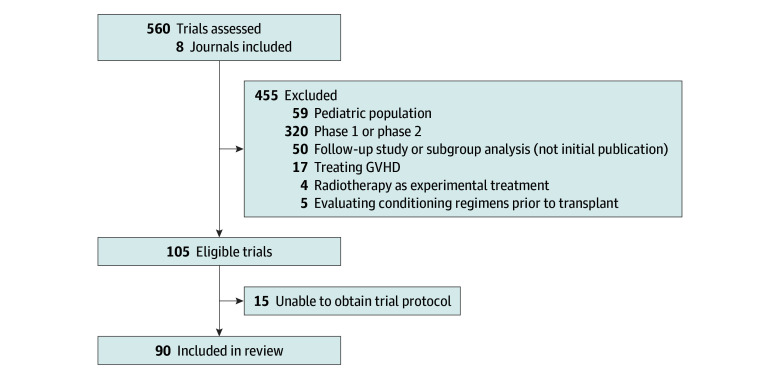

Ninety eligible phase 3 clinical trials were identified from the 8 journals (Figure).19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108 Concordance κ for investigator assessments of whether PROs were a prespecified end point, whether PROs were reported in the primary trial publication, and reported change in the PRO with the experimental treatment were 0.90, 0.96, and 0.97, respectively.

Figure. PRISMA Flowchart.

PRISMA flowchart summarizing review and selection process, including the number of excluded trials and the rationale for trial exclusion. GVHD indicates graft-vs-host disease.

Study Characteristics

Study characteristics are provided in Table 1, and individual studies analyzed are listed in eTable 1 in Supplement 1. The journals with the highest number of primary trial publications were the Journal of Clinical Oncology (25 trials [28%]) and the NEJM (20 trials [22%]). Overall, 30 (33%) reported data for plasma cell dyscrasias or multiple myeloma, 29 (32%) lymphoma, 28 (31%) leukemia or MDS, and 3 (3%) MPNs. Fifty-five trials (61%) were sponsored by a for-profit entity, while 35 (39%) were sponsored by a nonprofit entity. Eighty-three (92%) were superiority studies, while 7 (8%) were noninferiority studies. Seventy-one trials (79%) were open label, and most studies (77 [86%]) involved multiple nations. The most common therapeutic stage was first-line (49 [54%]). Experimental treatments included chemotherapy (22 [24%]), targeted therapy or immunotherapy (60 [67%]), cellular therapy (3 [3%]), growth factor or erythroid maturation agents (2 [2%]), transplantation (1 [1%]), or a combination (2 [2%]). Most trials (65 [72%]) used progression-free survival (PFS), event-free survival (EFS), or disease-free survival (DFS) as their primary end points. Sixty-two (69%) of the studies were positive, meeting 1 or more of their primary end points.

Table 1. Characteristics of 90 Primary Publications Included in the Analysis.

| Characteristic | Studies, No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Year of primary manuscript | |

| 2018 | 18 (20) |

| 2019 | 24 (27) |

| 2020 | 18 (20) |

| 2021 | 15 (17) |

| 2022 | 15 (17) |

| Primary manuscript journal | |

| NEJM | 20 (22) |

| Lancet | 8 (9) |

| Lancet Oncology | 17 (19) |

| Lancet Hematology | 11 (12) |

| Journal of Clinical Oncology | 25 (28) |

| Blood | 8 (9) |

| JAMA | 0 |

| JAMA Oncology | 1 (1) |

| Sources of funding | |

| Profit | 55 (61) |

| Nonprofit | 35 (39) |

| Type of malignancy | |

| Plasma cell dyscrasia | 30 (33) |

| Multiple myeloma | 25 (28) |

| Smoldering multiple myeloma | 1 (1) |

| Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia | 2 (2) |

| Light-chain amyloidosis | 2 (2) |

| Lymphoma | 29 (32) |

| Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma | 9 (10) |

| Mantle cell lymphoma | 2 (2) |

| Follicular lymphoma | 4 (4) |

| Hodgkin lymphoma | 3 (3) |

| T-cell lymphoma | 4 (4) |

| Primary CNS lymphoma | 1 (1) |

| Multiple | 6 (7) |

| Leukemia | 28 (31) |

| Acute myeloid leukemia | 9 (10) |

| Acute promyelocytic leukemia | 1 (1) |

| Acute lymphoblastic leukemia | 2 (2) |

| Chronic lymphocytic leukemia | 10 (11) |

| Chronic myeloid leukemia | 2 (2) |

| Myelodysplastic syndrome | 3 (3) |

| Multiple | 1 (1) |

| Myeloproliferative neoplasm | 3 (3) |

| Essential thrombocythemia | 1 (1) |

| Myelofibrosis | 1 (1) |

| Multiple | 1 (1) |

| Study design | |

| Superiority | 83 (92) |

| Noninferiority | 7 (8) |

| Masking | |

| Open label | 71 (79) |

| Double-masked | 19 (21) |

| Nations included | |

| Single nation | 13 (14) |

| China | 2 (2) |

| France | 1 (1) |

| Germany | 2 (2) |

| Italy | 1 (1) |

| United Kingdom | 1 (1) |

| US | 6 (7) |

| Multiple nations | 77 (86) |

| Type of experimental therapy | |

| Chemotherapy | 22 (24) |

| Targeted therapy or Immunotherapy | 60 (67) |

| Cellular therapy | 3 (3) |

| Growth factor or erythroid maturation agent | 2 (2) |

| Transplant | 1 (1) |

| Multiple | 2 (2) |

| Disease stage | |

| First-line | 49 (54) |

| Maintenance after first-line | 4 (4) |

| Maintenance after transplant | 3 (3) |

| Relapsed/refractory | 29 (32) |

| First-line and maintenance | 1 (1) |

| First-line and relapsed/refractory | 4 (4) |

| Primary end pointa | |

| PFS, EFS, or DFS | 65 (72) |

| Overall survival | 11 (12) |

| Response rateb | 15 (17) |

| Relapse rate | 1 (1) |

| Transfusion independence | 2 (2) |

| MRD negativity | 1 (1) |

| Maximum trough concentration | 1 (1) |

| Time to thrombosis, hemorrhage, or death from vascular causes | 1 (1) |

| Patient-reported outcomes | 1 (1) |

| Spleen volume reduction | 1 (1) |

| Positive results | |

| Yesc | 62 (69) |

| No | 28 (31) |

Abbreviations: CNS, central nervous system; DFS, disease-free survival; EFS, event-free survival; MRD, minimal residual disease; NEJM, New England Journal of Medicine; PFS, progression-free survival.

Categories not mutually exclusive.

Includes any type of response rate, including complete response, overall response rate, very good partial response, major erythroid response, hematological response, kidney response, major molecular response.

If study had multiple primary end points, it was considered positive if the experimental treatment demonstrated statistically significant improvement in at least one primary end point.

Inclusion of PROs as End Points

Twenty-four clinical trials (27%) did not include PROs as a prespecified end point. Among the 66 (73%) that did, only 1 RCT (1%) included PROs as a primary end point, 50 (56%) had PROs as a secondary end point, and 15 (17%) as an exploratory end point (Table 2). Trials that were sponsored by for-profit entities were more likely to include PROs as an end point compared with trials sponsored by nonprofit entities (49 of 55 [89%] vs 17 of 35 [49%]; P < .001) (Table 3). Trials involving plasma cell dyscrasias and/or multiple myeloma (27 of 30 [90%]) or MPNs (3 of 3 [100%]) were more likely to include PROs as an end point compared with trials involving lymphoma (18 of 29 [62%]) or leukemia and/or MDS (18 of 28 [64%]) (P = .03). There was no association between disease stage or positive primary end point results and inclusion of PROs as an end point. Lastly, trials involving time-limited treatment were less likely to include PROs as an end point compared with trials with indefinite treatment (24 of 43 [56%] vs 42 of 47 [89%]; P < .001).

Table 2. PROs in Phase 3 Studies of Hematologic Malignant Neoplasms.

| Characteristic | Studies, No. (%) (N = 90) |

|---|---|

| PRO listed as end point | 66 (73) |

| Primary | 1 (1) |

| Secondary | 50 (56) |

| Exploratory | 15 (17) |

| PRO not an end point | 24 (27) |

| Studies with PROs as end points (n = 66) | |

| Type documenteda | |

| General HRQOL | 65 (98) |

| Disease-specific metric | 36 (55) |

| Symptom-specific metric | 21 (32) |

| Collected during treatment | |

| Yes | 64 (97) |

| No | 1 (2) |

| Not recorded in protocol | 1 (2) |

| Collected at end-of-treatment visit | |

| Yes | 61 (92) |

| No | 3 (5) |

| Not recorded in protocol | 2 (3) |

| Collected after end-of-treatment visit, during follow-up | |

| Yes | 39 (59) |

| No | 24 (36) |

| Not recorded in protocol | 3 (5) |

| Reported in the primary publication (including data supplement) | |

| Yes | 26 (39) |

| No | 40 (61) |

| Subcohorts of studies with PROs as end point | |

| 2018-2019 studies with PRO data not reported in primary publication (n = 19) | |

| PRO data reported in a secondary publication or ASH/EHA meeting | |

| Yes | 8 (42) |

| No | 11 (58) |

| Studies with PROs reported in primary publication, secondary publication, or ASH/EHA meeting (n = 34) | |

| Change in PROs with experimental treatment | |

| Improvement | 13 (38) |

| No change | 21 (62) |

| Worsening | 0 |

Abbreviations: ASH, American Society of Hematology; EHA, European Hematology Association; HRQOL, health-related quality of life; PRO, patient-reported outcomes.

See Methods sections for list of measures.

Table 3. Associations Between Trial Characteristics and Inclusion of PROs as an End Point.

| Characteristic | Studies, No. (%)a | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PRO end point | No PRO end point | ||

| Source of funding | |||

| Profit | 49 (89) | 6 (11) | <.001 |

| Nonprofit | 17 (49) | 18 (51) | |

| Type of malignant neoplasm | |||

| Plasma cell dyscrasia | 27 (90) | 3 (10) | .03 |

| Lymphoma | 18 (62) | 11 (38) | |

| Leukemia | 18 (64) | 10 (36) | |

| MPN | 3 (100) | 0 | |

| Disease stageb | |||

| First-line | 33 (67) | 16 (33) | .23 |

| Relapsed or refractory | 24 (83) | 5 (17) | |

| Maintenance | 4 (57) | 3 (43) | |

| Positive study | |||

| Yes | 46 (74) | 16 (26) | .78 |

| No | 20 (71) | 8 (29) | |

| Time-limited treatment | |||

| Yes | 24 (56) | 19 (44) | <.001 |

| No | 42 (89) | 5 (11) | |

Abbreviations: MPN, myeloproliferative neoplasms; PRO, patient-reported outcomes.

These percentages reflect in-row relative frequencies.

Studies which spanned across different disease stages (n = 5) were omitted from univariable analysis.

Characteristics of PROs Included in Phase 3 Blood Cancer Trials

Of the 66 trials that included PROs as an end point, 65 (98%) collected general quality-of-life measures, including EORTC-QLQ-C30,109 EQ-5D,110 FACT-G,111 36-Item Short Form Survey (SF-36),112 Patient Report Outcome Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Cancer SF7a,113 MD Anderson Symptom Inventory (MDASI),114 General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12),115 Cancer Therapy Satisfaction Questionnaire (CTSQ),116 Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire for Medication (TSQM),116 Patient Global Impressions (PGI-C),117 and Work Productivity and Impairment Questionnaire (WPAI).118 Thirty-six (55%) collected disease-specific measures, including EORTC-QLQ subscales (eg, myeloma module [MY20], CLL module [CLL16]),109 FACT subscales (eg, leukemia, lymphoma, multiple myeloma, bone marrow transplant),111 or MDASI subscales (eg, CLL, CML, etc).114 Twenty-one (32%) collected symptom-specific metrics, including EORTC-QLQ subscales (eg, Chemotherapy-Induced Peripheral Neuropathy [CIPN20], Elderly Cancer Patients [ELD14]),109 FACT subscales (eg, neurotoxicity [NTX], fatigue, pain, dyspnea, anemia),111 PROMIS subscales (fatigue),113 Brief Pain Inventory,119 and ItchyQoL.120 Details regarding the PROs utilized for each disease type are included in eTable 2 in Supplement 1. With respect to timing of PRO collection, 64 trials (97%) collected PRO data during treatment, 61 (92%) at the end-of-treatment visit, and 39 (59%) greater than 1 month after the end-of-treatment visit.

Reporting of PRO Data in Primary and Secondary Publications

Of the 66 trials that included PROs as an end point, 26 (39%) reported these data in the primary trial publication. Of these, 8 (31%) reported improvement in PROs with the experimental treatment, while 18 (69%) reported no change. No trials reported worsening of PROs in the experimental treatment arm. Trials involving plasma cell dyscrasias and/or multiple myeloma (16 of 27 [59%]) or MPNs (2 of 3 [67%]) were more likely to report PRO data in the primary publication compared with trials involving lymphoma (3 of 18 [17%]) or leukemia and/or MDS (5 of 18 [28%]) (P = .01) (Table 4). There was no association between trial sponsorship, disease stage, or positive primary end point result with PRO reporting in primary publications. Furthermore, there was no association between positive primary end point result and whether improvement was reported in measured PROs. Trials involving time-limited treatment were less likely to report PRO results compared with trials involving indefinite treatment (4 of 24 [17%] vs 22 of 42 [52%]; P = .004).

Table 4. Associations Between Trial Characteristics and Reporting of PROs in Primary Publications (Among Studies That Included PROs as an End Point).

| Characteristics | Studies, No. (%)a | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PRO reported | PRO not reported | ||

| Source of funding | |||

| Profit | 20 (41) | 29 (59) | .69 |

| Nonprofit | 6 (35) | 11 (65) | |

| Type of malignant neoplasm | |||

| Plasma cell dyscrasia | 16 (59) | 11 (41) | .01 |

| Lymphoma | 3 (17) | 15 (83) | |

| Leukemia | 5 (28) | 13 (72) | |

| MPN | 2 (67) | 1 (33) | |

| Disease stageb | |||

| First-line | 11 (33) | 22 (67) | .22 |

| Relapsed or refractory | 7 (29) | 17 (71) | |

| Maintenance | 3 (75) | 1 (25) | |

| Positive study | |||

| Yes | 19 (41) | 27 (59) | .63 |

| No | 7 (35) | 13 (65) | |

| Time-limited treatment | |||

| Yes | 4 (17) | 20 (83) | .004 |

| No | 22 (52) | 20 (48) | |

Abbreviations: MPN, myeloproliferative neoplasms; PRO, patient-reported outcomes.

These percentages reflect in-row relative frequencies.

Studies which spanned across different disease stages (n = 5) were omitted from univariable analysis.

There were 19 trials published in 2018 and 2019 that included PROs as an end point but did not report PRO data in the primary trial publication. Of these, 6 (32%) had a secondary peer-reviewed publication with PROs by March 2023; the mean delay in publication time was 21 months. Four of these 6 trials (66%) reported improvement in PROs with the experimental treatment, while 2 (33%) reported no change and none reported worsening PROs with treatment. Of the 13 trials (68%) that did not have a secondary publication, only 2 reported comparative PRO data in an abstract published at a subsequent ASH or EHA annual meeting; of these, 1 (50%) reported improvement in PROs with experimental treatment, and 1 (50%) reported no change.

Discussion

PROs are critical to understanding patients’ perspectives about the functional, psychological, and physical effects of treatment. In contrast to our hypothesis (and to a prior analysis with a different definition of high-impact protocols), we found that PROs were included as an end point in a majority of therapeutic RCTs for hematological malignant neoplasms. However, PRO results were rarely reported in the primary trial publication, and when reported, were either improved or unchanged with the experimental treatment. These results reveal a critical gap in the dissemination of data on the lived experiences of patients with hematological malignant neoplasms during high-impact phase 3 clinical trials.

We identified significant differences between blood cancer disease groups regarding the collection and reporting of PRO data. For example, RCTs involving plasma cell disorders or multiple myeloma were significantly more likely to both collect and report PRO data in the associated primary publication. This contrasted with RCTs of lymphoma, leukemia, and MDS, where slightly over half of trials included PROs as an end point, and only a minority reported PRO results in the primary trial publication. One possible explanation is the increased adoption of triplet and/or quadruplet regimens as standard-of-care for the treatment of multiple myeloma; many of these regimens are not time-limited and therefore involve prolonged drug exposure, which may incentivize a more nuanced understanding by researchers of patient-reported adverse effects over time. In contrast, there may be less interest in measuring PROs for patients with lymphoma and aggressive leukemia, where treatments are most often of fixed-duration and time-limited decrements in HRQOL can be seen as the price to pay for a potential cure.

We did not identify a significant difference in the collection or reporting of PROs based on the line of treatment. One could argue that PRO data are particularly relevant for patients with relapsed or refractory disease, where clinicians must carefully balance disease control with patient symptoms and drug-related toxic effects. Reassuringly, we found that most RCTs in the relapsed and refractory settings included a PRO measure as an end point; however, only a relatively small fraction of these reported PRO data in the primary trial publication. Given that in many cases, later lines of therapy are associated with only incremental benefits in overall survival or surrogate end points,121 these data argue that there should be a more concerted effort to report PRO data in RCTs of relapsed and refractory patients, to allow clinicians and patients to make better decisions about the potential effectiveness of continued treatment.

We found that almost all RCTs that included a PRO as an end point collected PRO data through the end-of-treatment visit. However, less than two-thirds of these collected any PRO data more than 1 month after the end-of-treatment visit, suggesting a limited understanding of how treatments may affect long-term HRQOL. This finding is consistent with a prior report that found that 76% of primarily solid tumor oncology clinical trials published in 3 major journals between 2015 and 2018 assessed QoL during treatment, but fewer than 25% of RCTs continued PRO data collection until disease progression and fewer than 3% until patient death.16 While longer-term PRO data collection is challenging and resource intensive, it can leverage the RCT infrastructure to provide valuable insight into the natural history of HRQOL for each disease, even after the conclusion of treatment.

Only 1 RCT in our analysis included PROs as a primary end point; the most popular primary end points were surrogate survival metrics (PFS, EFS, DFS), overall survival, and response rate. We did not identify any association between positive trial results and inclusion of PROs as an end point or reporting of PRO data in the primary publication. Notably, 26% of positive RCTs did not include a PRO among the study end points, and 59% of positive RCTs that did have a PRO end point did not report PRO data in the primary trial publication. These data suggest that PROs are not readily available for many treatment regimens that are subsequently incorporated into routine clinical practice. At the very least, investigators for RCTs of hematological malignant neoplasms should be encouraged to report these results if they are available at the time of trial publication.

Indeed, lack of supporting PRO data has been previously identified. For example, Davis and colleagues122 showed that between 2009 and 2013, only 10% of EMA cancer drug approvals had evidence of improved HRQOL for patients. This issue is further compounded by potential publication bias: in our analysis, among the studies that reported PRO data either in the primary trial publication or a subsequent manuscript or abstract, none reported worsening of PROs with the experimental treatment. Combined with prior studies suggesting that RCTs that fail to show improvement in PROs often frame PRO outcomes in an undeservedly favorable light,123,124 this finding suggests a need for more stringent collecting and reporting requirements for PROs in blood cancer RCTs, such that detrimental impacts on HRQOL cannot be easily omitted from trial publications.

Limitations

Our analysis has limitations. First, our data were limited to a subset of journals and calendar years, and our sample of RCTs is likely not fully representative of all therapeutic phase 3 trials for hematological malignant neoplasms. Our choice to focus on a subset of high-impact journals was intended to isolate RCTs that were most likely to inform clinical practice; however, we recognize that our study population is therefore likely to be enriched for RCTs that were able to meet their primary end points or demonstrate other hard outcomes. Second, given the relatively short timeframe included in our study, we were unable to assess whether there have been changes in the collection and reporting of PROs over time, particularly after the publication of guideline statements for PROs for RCTs.125,126 Third, our statistical analysis was limited by relatively small sample size, and we were not able to adjust for multiple comparisons or conduct multivariable analyses. In particular, our univariable analyses for RCTs dedicated to MPNs were limited, as only 3 such trials were included in our systematic review. Furthermore, the small sample size precluded our ability to analyze associations between individual PROs and trial characteristics. Finally, our study did not include pediatric RCTs; given similar concerns about suboptimal utilization of PROs in pediatric trials,127,128 we believe that a secondary review focused on this population is warranted.

Conclusions

In contrast to prior work, we found that almost 3 of every 4 therapeutic RCTs for hematological malignant neoplasms collected PRO data; however, only 1 RCT included PROs as a primary end point. Moreover, a minority of studies reported these data in the associated primary publication, and when reported, PROs were either better or unchanged, raising concerns for publication bias. Our analysis suggests a critical gap in dissemination of data on the lived experiences of patients with hematological malignant neoplasms during phase 3 trials, which may be addressed with more inclusive PRO design and more stringent reporting requirements.

eTable 1. List of Reviewed Trials

eTable 2. Aggregated PROs Used in Reviewed RCTs

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Trotti A, Colevas AD, Setser A, Basch E. Patient-reported outcomes and the evolution of adverse event reporting in oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(32):5121-5127. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.4784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Basch E. The missing voice of patients in drug-safety reporting. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(10):865-869. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0911494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fromme EK, Eilers KM, Mori M, Hsieh YC, Beer TM. How accurate is clinician reporting of chemotherapy adverse effects? A comparison with patient-reported symptoms from the Quality-of-Life Questionnaire C30. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(17):3485-3490. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.03.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Di Maio M, Gallo C, Leighl NB, et al. Symptomatic toxicities experienced during anticancer treatment: agreement between patient and physician reporting in three randomized trials. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(8):910-915. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.57.9334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Di Maio M, Basch E, Bryce J, Perrone F. Patient-reported outcomes in the evaluation of toxicity of anticancer treatments. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2016;13(5):319-325. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2015.222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Basch E, Iasonos A, McDonough T, et al. Patient versus clinician symptom reporting using the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events: results of a questionnaire-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7(11):903-909. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70910-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Atkinson TM, Ryan SJ, Bennett AV, et al. The association between clinician-based common terminology criteria for adverse events (CTCAE) and patient-reported outcomes (PRO): a systematic review. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24(8):3669-3676. doi: 10.1007/s00520-016-3297-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Veitch ZW, Shepshelovich D, Gallagher C, et al. Underreporting of symptomatic adverse events in phase i clinical trials. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2021;113(8):980-988. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djab015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takenaga T, Kuji S, Tanabe KI, et al. Prospective analysis of patient-reported outcomes and physician-reported outcomes with gynecologic cancer chemotherapy. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2024;50(1):75-85. doi: 10.1111/jog.15811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Basch E, Jia X, Heller G, et al. Adverse symptom event reporting by patients vs clinicians: relationships with clinical outcomes. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101(23):1624-1632. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schnipper LE, Davidson NE, Wollins DS, et al. ; American Society of Clinical Oncology . American Society of Clinical Oncology Statement: a conceptual framework to assess the value of cancer treatment options. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(23):2563-2577. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.61.6706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cherny NI, Sullivan R, Dafni U, et al. A standardised, generic, validated approach to stratify the magnitude of clinical benefit that can be anticipated from anti-cancer therapies: the European Society for Medical Oncology Magnitude of Clinical Benefit Scale (ESMO-MCBS). Ann Oncol. 2015;26(8):1547-1573. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bylicki O, Gan HK, Joly F, Maillet D, You B, Péron J. Poor patient-reported outcomes reporting according to CONSORT guidelines in randomized clinical trials evaluating systemic cancer therapy. Ann Oncol. 2015;26(1):231-237. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marandino L, La Salvia A, Sonetto C, et al. Deficiencies in health-related quality-of-life assessment and reporting: a systematic review of oncology randomized phase 3 trials published between 2012 and 2016. Ann Oncol. 2018;29(12):2288-2295. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Le Saux O, Falandry C, Gan HK, You B, Freyer G, Péron J. Changes in the use of end points in clinical trials for elderly cancer patients over time. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(10):2606-2611. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haslam A, Herrera-Perez D, Gill J, Prasad V. Patient experience captured by quality-of-life measurement in oncology clinical trials. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(3):e200363. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.0363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Al Hadidi S, Kamble RT, Carrum G, Heslop HE, Ramos CA. Assessment and reporting of quality-of-life measures in pivotal clinical trials of hematological malignancies. Blood Adv. 2021;5(22):4630-4633. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2021004190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.The Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine . Oxford Center for Evidence-based Medicine’s Levels of Evidence and Grades of Recommendation. Accessed June 17, 2023. https://www.cebm.net

- 19.Godfrey AL, Campbell PJ, MacLean C, et al. Hydroxycarbamide plus aspirin versus aspirin alone in patients with essential thrombocythemia age 40 to 59 years without high-risk features. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(34):3361-3369. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2018.78.8414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mascarenhas J, Kosiorek HE, Prchal JT, et al. A randomized phase 3 trial of interferon-α vs hydroxyurea in polycythemia vera and essential thrombocythemia. Blood. 2022;139(19):2931-2941. doi: 10.1182/blood.2021012743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mascarenhas J, Hoffman R, Talpaz M, et al. Pacritinib vs best available therapy, including ruxolitinib, in patients with myelofibrosis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4(5):652-659. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.5818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kastritis E, Palladini G, Minnema MC, et al. Daratumumab-based treatment for immunoglobulin light-chain amyloidosis. NEJM. 2021;385(1):46-58. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2028631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kastritis E, Leleu X, Arnulf B, et al. Bortezomib, melphalan, and dexamethasone for light-chain amyloidosis. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(28):3252-3260. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.01285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Richardson PG, Jacobus SJ, Weller EA, et al. Triplet therapy, transplantation, and maintenance until progression in myeloma. NEJM. 2022;387(2):132-147. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2204925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Facon T, Kumar S, Plesner T, et al. Daratumumab plus lenalidomide and dexamethasone for untreated myeloma. NEJM. 2019;380(22):2104-2115. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1817249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mateos M-V, Dimopoulos MA, Cavo M, et al. Daratumumab plus bortezomib, melphalan, and prednisone for untreated myeloma. NEJM. 2018;378(6):518-528. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1714678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moreau P, Dimopoulos M-A, Mikhael J, et al. Isatuximab, carfilzomib, and dexamethasone in relapsed multiple myeloma (IKEMA): a multicentre, open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2021;397(10292):2361-2371. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00592-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grosicki S, Simonova M, Spicka I, et al. Once-per-week selinexor, bortezomib, and dexamethasone versus twice-per-week bortezomib and dexamethasone in patients with multiple myeloma (BOSTON): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2020;396(10262):1563-1573. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32292-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Usmani SZ, Quach H, Mateos M-V, et al. Carfilzomib, dexamethasone, and daratumumab versus carfilzomib and dexamethasone for patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma (CANDOR): results from a randomised, multicentre, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2022;23(1):65-76. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00579-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Attal M, Richardson PG, Rajkumar SV, et al. Isatuximab plus pomalidomide and low-dose dexamethasone versus pomalidomide and low-dose dexamethasone in patients with relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma (ICARIA-MM): a randomised, multicentre, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet. 2019;394(10214):2096-2107. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32556-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dimopoulos MA, Gay F, Schjesvold F, et al. Oral ixazomib maintenance following autologous stem cell transplantation (TOURMALINEMM3): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2019;393(10168):253-264. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)33003-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dimopoulos MA, Terpos E, Boccadoro M, et al. Daratumumab plus pomalidomide and dexamethasone versus pomalidomide and dexamethasone alone in previously treated multiple myeloma (APOLLO): an open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(6):801-812. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00128-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kumar SK, Harrison SJ, Cavo M, et al. Venetoclax or placebo in combination with bortezomib and dexamethasone in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma (BELLINI): a randomised, double-blind, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(12):1630-1642. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30525-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kumar SK, Jacobus SJ, Cohen AD, et al. Carfilzomib or bortezomib in combination with lenalidomide and dexamethasone for patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma without intention for immediate autologous stemcell transplantation (ENDURANCE): a multicentre, open-label, phase 3, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(10):1317-1330. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30452-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Richardson PG, Oriol A, Beksac M, et al. Pomalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone for patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma previously treated with lenalidomide (OPTIMISMM): a randomised, openlabel, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(6):781-794. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30152-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jackson GH, Davies FE, Pawlyn C, et al. Lenalidomide maintenance versus observation for patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (Myeloma XI): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(1):57-73. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30687-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moreau P, Mateos M-V, Berenson JR, et al. Once weekly versus twice weekly carfilzomib dosing in patients with relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma (A.R.R.O.W.): interim analysis results of a randomised, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19(7):953-964. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30354-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goldschmidt H, Mai EK, Bertsch U, et al. Addition of isatuximab to lenalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone as induction therapy for newly diagnosed, transplantation-eligible patients with multiple myeloma (GMMG-HD7): part 1 of an open-label, multicentre, randomised, active-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Haematol. 2022;9(11):e810-e821. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(22)00263-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dimopoulos MA, Richardson PG, Bahlis NJ, et al. Addition of elotuzumab to lenalidomide and dexamethasone for patients with newly diagnosed, transplantation ineligible multiple myeloma (ELOQUENT-1): an open-label, multicentre, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Haematol. 2022;9(6):e403-e414. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(22)00103-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schjesvold FH, Dimopoulas M-A, Delimpasi S, et al. Melflufen or pomalidomide plus dexamethasone for patients with multiple myeloma refractory to lenalidomide (OCEAN): a randomised, head-to-head, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet Haematol. 2022;9(2):e98-e110. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(21)00381-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mateos M-V, Nahi H, Legiec W, et al. Subcutaneous versus intravenous daratumumab in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma (COLUMBA): a multicentre, open-label, non-inferiority, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Haematol. 2020;7(5):e370-e380. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(20)30070-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jackson GH, Davies FE, Pawlyn C, et al. Response-adapted intensification with cyclophosphamide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone versus no intensification in patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (Myeloma XI): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Haematol. 2019;6(12):e616-e629. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(19)30167-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Usmani SZ, Schjesvold F, Oriol A, et al. Pembrolizumab plus lenalidomide and dexamethasone for patients with treatment-naïve multiple myeloma (KEYNOTE-185): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Haematol. 2019;6(9):e448-e458. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(19)30109-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mateos M-V, Blacklock H, Schjesvold F, et al. Pembrolizumab plus pomalidomide and dexamethasone for patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma (KEYNOTE-183): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Haematol. 2019;6(9):e459-e469. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(19)30110-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dimopoulos MA, Spicka I, Quach H, et al. Ixazomib as postinduction maintenance for patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma not undergoing autologous stem cell transplantation: the phase III TOURMALINE-MM4 Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(34):4030-4041. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.02060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bridoux F, Arnulf B, Karlin L, et al. Randomized trial comparing double versus triple bortezomib-based regimen in patients with multiple myeloma and acute kidney injury due to cast nephropathy. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(23):2647-2657. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.00298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stadtmauer EA, Pasquini MC, Blackwell B, et al. Autologous transplantation, consolidation, and maintenance therapy in multiple myeloma: results of the BMT CTN 0702 Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(7):589-597. doi: 10.1200/JCO.18.00685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Facon T, Venner CP, Bahlis NJ, et al. Oral ixazomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone for transplant-ineligible patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Blood. 2021;137(26):3616-3628. doi: 10.1182/blood.2020008787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lonial S, Jacobus S, Fonseca R, et al. Randomized trial of lenalidomide versus observation in smoldering multiple myeloma. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(11):1126-1137. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.01740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dimopoulos MA, Tedeschi A, Trotman J, et al. Phase 3 trial of ibrutinib plus rituximab in Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia. NEJM. 2018;378(25):2399-2410. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1802917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tam CS, Opat S, D’Sa S, et al. A randomized phase 3 trial of zanubrutinib vs ibrutinib in symptomatic Waldenström macroglobulinemia: the ASPEN study. Blood. 2020;136(18):2038-2050. doi: 10.1182/blood.2020006844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tilly H, Morschhauser F, Sehn LH, et al. Polatuzumab vedotin in previously untreated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. NEJM. 2022;386(4):351-363. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2115304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kamdar M, Solomon SR, Arnason J, et al. Lisocabtagene maraleucel versus standard of care with salvage chemotherapy followed by autologous stem cell transplantation as second-line treatment in patients with relapsed or refractory large B-cell lymphoma (TRANSFORM): results from an interim analysis of an open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2022;399(10343):2294-2308. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00662-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Davies A, Cummin TE, Barrans S, et al. Gene-expression profiling of bortezomib added to standard chemoimmunotherapy for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (REMoDL-B): an open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(5):649-662. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30935-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nowakowski GS, Chiappella A, Gascoyne RD, et al. ROBUST: a phase III study of lenalidomide plus R-CHOP versus placebo plus R-CHOP in previously untreated patients with ABC-type diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(12):1317-1328. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.01366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Oberic L, Peyrade F, Puyade M, et al. Subcutaneous rituximab-MiniCHOP compared with subcutaneous rituximab-MiniCHOP plus lenalidomide in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma for patients age 80 years or older. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(11):1203-1213. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.02666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lugtenburg PJ, Brown PN, van der Holt B, et al. Rituximab-CHOP with early rituximab intensification for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: a randomized phase III trial of the HOVON and the Nordic Lymphoma Group (HOVON-84). J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(29):3377-3387. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.03418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bartlett NL, Wilson WH, Jung S-H, et al. Dose-adjusted EPOCH-R compared with R-CHOP as frontline therapy for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: clinical outcomes of the Phase III Intergroup Trial Alliance/CALGB 50303. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(21):1790-1799. doi: 10.1200/JCO.18.01994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Younes A, Sehn LH, Johnson P, et al. Randomized phase III trial of ibrutinib and rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone in non–germinal center B-cell diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(15):1285-1295. doi: 10.1200/JCO.18.02403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Le Gouill S, Ghesquières H, Oberic L, et al. Obinutuzumab vs rituximab for advanced DLBCL: a PET-guided and randomized phase 3 study by LYSA. Blood. 2021;137(17):2307-2320. doi: 10.1182/blood.2020008750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Morschhauser F, Fowler NH, Feugier P, et al. Rituximab plus lenalidomide in advanced untreated follicular lymphoma. NEJM. 2018;379(10):934-947. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1805104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ogura M, Sancho JM, Cho S-G, et al. Efficacy, pharmacokinetics, and safety of the biosimilar CT-P10 in comparison with rituximab in patients with previously untreated low-tumour-burden follicular lymphoma: a randomised, double-blind, parallel-group, phase 3 trial. Lancet Haematol. 2018;5(11):e543-e553. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(18)30157-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Luminari S, Manni M, Galimberti S, et al. Response-adapted postinduction strategy in patients with advanced-stage follicular lymphoma: the FOLL12 Study. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(7):729-739. doi: 10.1200/JCO.21.01234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.MacManus M, Fisher R, Roos D, et al. Randomized trial of systemic therapy after involved-field radiotherapy in patients with early-stage follicular lymphoma: TROG 99.03. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(29):2918-2925. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2018.77.9892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Connors JM, Jurczak W, Straus DJ, et al. Brentuximab vedotin with chemotherapy for stage III or IV Hodgkin’s lymphoma. NEJM. 2018;378(4):331-344. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1708984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kuruvilla J, Ramchandren R, Santoro A, et al. Pembrolizumab versus brentuximab vedotin in relapsed or refractory classical Hodgkin lymphoma (KEYNOTE-204): an interim analysis of a multicentre, randomised, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(4):512-524. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00005-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Casasnovas R-O, Bouabdallah R, Brice P, et al. PET-adapted treatment for newly diagnosed advanced Hodgkin lymphoma (AHL2011): a randomised, multicentre, non-inferiority, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(2):202-215. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30784-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wang ML, Jurczak W, Jerkeman M, et al. Ibrutinib plus bendamustine and rituximab in untreated mantle-cell lymphoma. NEJM. 2022;386(26):2482-2494. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2201817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ladetto M, Cortelazzo S, Ferrero S, et al. Lenalidomide maintenance after autologous haematopoietic stem-cell transplantation in mantle cell lymphoma: results of a Fondazione Italiana Linfomi (FIL) multicentre, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Haematol. 2021;8(1):e34-e44. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(20)30358-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dührsen U, Müller S, Hertenstein B, et al. Positron Emission Tomography–Guided Therapy of Aggressive Non-Hodgkin Lymphomas (PETAL): a multicenter, randomized phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(20):2024-2034. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.76.8093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bishop MR, Dickinson M, Purtill D, et al. Second-line tisagenlecleucel or standard care in aggressive B-cell lymphoma. NEJM. 2022;386(7):629-639. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2116596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Locke FL, Miklos DB, Jacobson CA, et al. Axicabtagene ciloleucel as second-line therapy for large B-cell lymphoma. NEJM. 2022;386(7):640-654. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2116133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Poeschel V, Held G, Ziepert M, et al. Four versus six cycles of CHOP chemotherapy in combination with six applications of rituximab in patients with aggressive B-cell lymphoma with favourable prognosis (FLYER): a randomised, phase 3, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2019;394(10216):2271-2281. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)33008-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Matasar MJ, Capra M, Özcan M, et al. Copanlisib plus rituximab versus placebo plus rituximab in patients with relapsed indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma (CHRONOS-3): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(5):678-689. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00145-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Leonard JP, Trneny M, Izutsu K, et al. AUGMENT: a phase III study of lenalidomide plus rituximab versus placebo plus rituximab in relapsed or refractory indolent lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(14):1188-1199. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.00010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bromberg JEC, Issa S, Bakunina K, et al. Rituximab in patients with primary CNS lymphoma (HOVON 105/ALLG NHL 24): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 intergroup study. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(2):216-228. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30747-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kim YH, Bagot M, Pinter-Brown L, et al. Mogamulizumab versus vorinostat in previously treated cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (MAVORIC): an international, open-label, randomised, controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19(9):1192-1204. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30379-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Horwitz S, O’Connor OA, Pro B, et al. Brentuximab vedotin with chemotherapy for CD30-positive peripheral T-cell lymphoma (ECHELON-2): a global, double-blind, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2019;393(10168):229-240. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32984-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bachy E, Camus V, Thieblemont C, et al. Romidepsin plus CHOP versus CHOP in patients with previously untreated peripheral T-cell lymphoma: results of the Ro-CHOP phase III study (conducted by LYSA). J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(3):242-251. doi: 10.1200/JCO.21.01815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.O’Connor OA, Özcan M, Jacobsen ED, et al. Randomized phase III study of alisertib or investigator’s choice (selected single agent) in patients with relapsed or refractory peripheral T-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(8):613-623. doi: 10.1200/JCO.18.00899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Marks DI, Kirkwood AA, Rowntree CJ, et al. Addition of four doses of rituximab to standard induction chemotherapy in adult patients with precursor B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (UKALL14): a phase 3, multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Haematol. 2022;9(4):e262-e275. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(22)00038-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Huguet F, Chevret S, Leguay T, et al. Intensified therapy of acute lymphoblastic leukemia in adults: report of the Randomized GRAALL-2005 clinical trial. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(24):2514-2523. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.76.8192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Montesinos P, Recher C, Vives S, et al. Ivosidenib and azacitidine in IDH1-mutated acute myeloid leukemia. NEJM. 2022;386(16):1519-1531. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2117344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wei AH, Döhner H, Pocock C, et al. Oral azacitidine maintenance therapy for acute myeloid leukemia in first remission. NEJM. 2020;383(26):2526-2537. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2004444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.DiNardo CD, Jonas BA, Pullarkat V, et al. Azacitidine and venetoclax in previously untreated acute myeloid leukemia. NEJM. 2020;383(7):617-629. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2012971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Perl AE, Martinelli G, Cortes JE, et al. Gilteritinib or chemotherapy for relapsed or refractory FLT3-mutated AML. NEJM. 2019;381(18):1728-1740. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1902688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Xuan L, Wang Y, Huang F, et al. Sorafenib maintenance in patients with FLT3-ITD acute myeloid leukaemia undergoing allogeneic haematopoietic stem-cell transplantation: an open-label, multicentre, randomized phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(9):1201-1212. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30455-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Cortes JE, Khaled S, Martinelli G, et al. Quizartinib versus salvage chemotherapy in relapsed or refractory FLT3-ITD acute myeloid leukaemia (QuANTUM-R): a multicentre, randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(7):984-997. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30150-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Schlenk RF, Paschka P, Krzykalla J, et al. Gemtuzumab ozogamicin in NPM1-mutated acute myeloid leukemia: early results from the prospective randomized AMLSG 09-09 phase III study. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(6):623-632. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.01406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lancet LE, Uy GL, Cortes JE, et al. CPX-351 (cytarabine and daunorubicin) liposome for injection versus conventional cytarabine plus daunorubicin in older patients with newly diagnosed secondary acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(26):2684-2692. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.77.6112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wei AH, Montesinos P, Ivanov V, et al. Venetoclax plus LDAC for newly diagnosed AML ineligible for intensive chemotherapy: a phase 3 randomized placebo-controlled trial. Blood. 2020;135(24):2137-2145. doi: 10.1182/blood.2020004856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Huls G, Chitu DA, Havelange V, et al. Azacitidine maintenance after intensive chemotherapy improves DFS in older AML patients. Blood. 2019;133(13):1457-1464. doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-10-879866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Zhu H-H, Wu D-P, Du X, et al. Oral arsenic plus retinoic acid versus intravenous arsenic plus retinoic acid for non-high-risk acute promyelocytic leukaemia: a non-inferiority, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19(7):871-879. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30295-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Shanafelt TD, Wang XV, Kay NE, et al. Ibrutinib–rituximab or chemoimmunotherapy for chronic lymphocytic leukemia. NEJM. 2019;381(5):432-443. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1817073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Fischer K, Al-Sawaf O, Bahlo J, et al. Venetoclax and obinutuzumab in patients with CLL and coexisting conditions. NEJM. 2019;380(23):2225-2236. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1815281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Woyach JA, Ruppert AS, Heerema NA, et al. Ibrutinib regimens versus chemoimmunotherapy in older patients with untreated CLL. NEJM. 2018;379(26):2517-2528. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1812836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Seymour JF, Kipps TJ, Eichhorst B, et al. Venetoclax–rituximab in relapsed or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia. NEJM. 2018;378(12):1107-1120. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1713976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Tam CS, Brown JR, Kahl BS, et al. Zanubrutinib versus bendamustine and rituximab in untreated chronic lymphocytic leukaemia and small lymphocytic lymphoma (SEQUOIA): a randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2022;23(8):1031-1043. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(22)00293-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Moreno C, Greil R, Demirkan F, et al. Ibrutinib plus obinutuzumab versus chlorambucil plus obinutuzumab in first-line treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (iLLUMINATE): a multicentre, randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(1):43-56. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30788-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Sharman JP, Brander DM, Mato AR, et al. Ublituximab plus ibrutinib versus ibrutinib alone for patients with relapsed or refractory high-risk chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (GENUINE): a phase 3, multicentre, open-label, randomised trial. Lancet Haematol. 2021;8(4):e254-e266. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(20)30433-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Byrd JC, Hillmen P, Ghia P, et al. Acalabrutinib versus ibrutinib in previously treated chronic lymphocytic leukemia: results of the first randomized phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(31):3441-3452. doi: 10.1200/JCO.21.01210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Ghia P, Pluta A, Wach M, et al. ASCEND: phase III, randomized trial of acalabrutinib versus idelalisib plus rituximab or bendamustine plus rituximab in relapsed or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(25):2849-2861. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.03355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Flinn IW, Hillmen P, Montillo M, et al. The phase 3 DUO trial: duvelisib vs ofatumumab in relapsed and refractory CLL/SLL. Blood. 2018;132(23):2446-2455. doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-05-850461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Cortes JE, Gambacorti-Passerini C, Deininger MW, et al. Bosutinib versus imatinib for newly diagnosed chronic myeloid leukemia: results from the randomized BFORE trial. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(3):231-237. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.74.7162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Réa D, Mauro MJ, Boquimpani C, et al. A phase 3, open-label, randomized study of asciminib, a STAMP inhibitor, vs bosutinib in CML after 2 or more prior TKIs. Blood. 2021;138(21):2031-2041. doi: 10.1182/blood.2020009984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Fenaux P, Platzbecker U, Mufti GJ, et al. Luspatercept in patients with lower-risk myelodysplastic syndromes. NEJM. 2020;382(2):140-151. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1908892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Garcia-Manero G, Santini V, Almeida A, et al. Phase III, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of CC-486 (oral azacitidine) in patients with lower-risk myelodysplastic syndromes. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(13):1426-1436. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.02619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.List AF, Sun Z, Verma A, et al. Lenalidomide-epoetin alfa versus lenalidomide monotherapy in myelodysplastic syndromes refractory to recombinant erythropoietin. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(9):1001-1009. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.01691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer . EORTC Questionnaires. Accessed December 1, 2023. https://qol.eortc.org/questionnaires/

- 110.EuroQOL . EQ-5D-3L information page. Accessed December 1, 2023. https://euroqol.org/information-and-support/euroqol-instruments/eq-5d-3l/

- 111.FACIT Group . FACT Measures. Accessed December 1, 2023. https://www.facit.org/facit-measures-searchable-library

- 112.RAND Corporation . 36-Item Short Form Survey (SF-36). Accessed December 1, 2023. https://www.rand.org/health-care/surveys_tools/mos/36-item-short-form.html

- 113.PROMIS Health Organization . Accessed December 1, 2023. https://www.promishealth.org/57461-2/

- 114.University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center . The MD Anderson Symptom Inventory. Accessed December 1, 2023. https://www.mdanderson.org/research/departments-labs-institutes/departments-divisions/symptom-research/symptom-assessment-tools/md-anderson-symptom-inventory.html

- 115.USAID . Accessed December 1, 2023. https://www.advancingnutrition.org/resources/caregiver-toolkit/mental-health/general-health-questionnaire-ghq-12

- 116.IQVIA . Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire for Medication (TSQM). Accessed December 1, 2023. https://www.iqvia.com/library/fact-sheets/treatment-satisfaction-questionnaire-for-medication-tsqm

- 117.National Institute of Mental Health . Patient Global Impressions scale—Change, Improvement, Severity (PGI-C, PGI-I, PGI-S). Accessed December 1, 2023. https://eprovide.mapi-trust.org/instruments/patient-global-impressions-scale-change-improvement-severity

- 118.Reilly Associates . Accessed December 1, 2023. http://www.reillyassociates.net

- 119.University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center . Brief Pain Inventory. Accessed December 1, 2023. https://www.mdanderson.org/research/departments-labs-institutes/departments-divisions/symptom-research/symptom-assessment-tools/brief-pain-inventory.html

- 120.Emory University . Itchy QoL: A Pruritus-Specific Quality of Life Instrument. March 26, 2009. Accessed December 1, 2023. https://emoryott.technologypublisher.com/tech?title=ItchyQol%3a_A_Pruritus-Specific_Quality_of_Life_Instrument

- 121.Michaeli DT, Michaeli T. Overall survival, progression-free survival, and tumor response benefit supporting initial US Food and Drug Administration approval and indication extension of new cancer drugs, 2003-2021. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(35):4095-4106. doi: 10.1200/JCO.22.00535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Davis C, Naci H, Gurpinar E, Poplavska E, Pinto A, Aggarwal A. Availability of evidence of benefits on overall survival and quality of life of cancer drugs approved by European Medicines Agency: retrospective cohort study of drug approvals 2009-13. BMJ. 2017;359:j4530. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j4530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Samuel JN, Booth CM, Eisenhauer E, Brundage M, Berry SR, Gyawali B. Association of quality-of-life outcomes in cancer drug trials with survival outcomes and drug class. JAMA Oncol. 2022;8(6):879-886. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2022.0864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Gyawali B, Shimokata T, Honda K, Ando Y. Reporting harms more transparently in trials of cancer drugs. BMJ. 2018;363:k4383. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k4383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Calvert M, Blazeby J, Altman DG, Revicki DA, Moher D, Brundage MD; CONSORT PRO Group . Reporting of patient-reported outcomes in randomized trials: the CONSORT PRO extension. JAMA. 2013;309(8):814-822. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Calvert M, Kyte D, Mercieca-Bebber R, et al. ; the SPIRIT-PRO Group . Guidelines for inclusion of patient-reported outcomes in clinical trial protocols: the SPIRIT-PRO Extension. JAMA. 2018;319(5):483-494. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.21903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Murugappan MN, King-Kallimanis BL, Reaman GH, et al. Patient-reported outcomes in pediatric cancer registration trials: a US Food and Drug Administration perspective. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2022;114(1):12-19. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djab087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Riedl D, Rothmund M, Darlington AS, Sodergren S, Crazzolara R, de Rojas T; EORTC Quality of Life Group . Rare use of patient-reported outcomes in childhood cancer clinical trials—a systematic review of clinical trial registries. Eur J Cancer. 2021;152:90-99. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2021.04.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. List of Reviewed Trials

eTable 2. Aggregated PROs Used in Reviewed RCTs

Data Sharing Statement