Abstract

Practical relevance:

Non-hemotropic Mycoplasma species are frequently implicated in cases of respiratory disease, and also conjunctivitis, in cats.

Clinical challenges:

Mycoplasma species are considered commensal bacteria of the conjunctiva and the upper respiratory tract of cats, and hence their role as a primary pathogen is difficult to determine. These organisms certainly appear to play a significant role as a secondary pathogen in the upper airways, and there is increasing evidence that in some animals they may represent a primary infection. However, mycoplasmas have not been found in the lower airways of clinically healthy cats – suggesting that, when present, they likely represent a pathologic process. Diagnostic challenges exist as well; Mycoplasma species are not typically identified via cytology due to their small size, and culture of these organisms requires special media and handling. Although PCR has improved identification and allowed for speciation, conflicting culture and PCR results can create a dilemma regarding the clinical relevance of infection.

Evidence base:

This article draws on original research and case reports to provide information about the role of Mycoplasma species in thefeline upper and lower respiratory tract, diagnostic methods and associated challenges, and treatment options.

Audience:

The goal is to provide small animal practitioners with a current and organized review of the often-conflicting literature regarding the role of Mycoplasma species in feline respiratory infections.

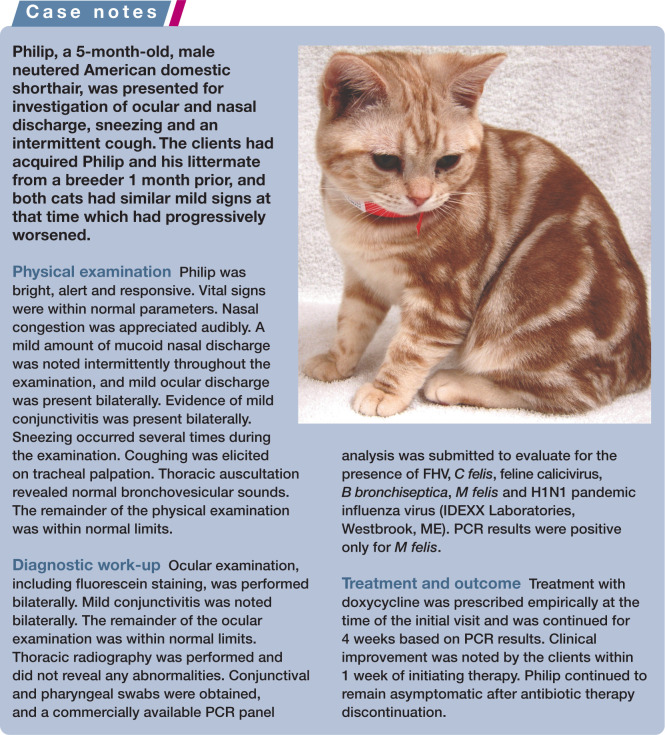

Non-hemotropic mycoplasmas and respiratory disease

Mycoplasmas, members of the class Mollicutes, are the smallest known prokaryotes, lack a cell wall and require sterols for growth. They are widely considered to be commensal organisms associated with mammalian mucosal membranes. While there are well over 100 different species of Mycoplasma, this review will focus on those non-hemotropic mycoplasmas reported to affect cats, and, more specifically, the respiratory system.1,2 The role of Mycoplasma species as a primary pathogen in conjunctivitis3 –5 and upper respiratory tract disease (URTD) is still heavily debated; however, the organism is at least considered to contribute to these conditions as a secondary infection. Diseases of the lower respiratory tract and pleural cavity have been reported with Mycoplasma species as a primary pathogen.6 –17

Upper respiratory tract disease

URTD is a significant concern in the feline population, particularly in a shelter environment. Viral infections, such as feline calicivirus and feline herpesvirus (FHV), and bacterial organisms, such as Bordetella bronchiseptica and Chlamydophila felis, play a significant role in URTD. The currently understood role of mycoplasmas as a potential primary pathogen in URTD is controversial. Mycoplasma species are part of the normal flora of the upper respiratory tract. While these organisms are often identified in cats with URTD, they have also been isolated from the upper respiratory tract of clinically normal, asymptomatic cats.18 –20 One study evaluated cats with URTD and their asymptomatic housemates, and isolated Mycoplasma felis from both groups. 18 Another study evaluating a shelter population documented a high prevalence of M felis infection in cats that remained healthy. 19 It is important to note that while cats in these studies were asymptomatic for URTD, they could possibly serve as carriers of infection.

Other studies, in both shelter animals and cats presenting to veterinary hospitals, indicate a significant association between Mycoplasma species and URTD.18,21 –24 One study documented the presence of Mycoplasma species in seven shelter cats with URTD in which no primary pathogen was identified. 22 An additional study of 40 humane society cats with rhinitis isolated Mycoplasma species as the sole pathogen in 5% of cats. 25 These results suggest that mycoplasmas may act as primary pathogens in some cats.

Regardless of whether mycoplasmas act as a primary or secondary pathogen, identifying and addressing their presence in URTD patients should be considered.

Lower respiratory tract disease

To date, Mycoplasma species have not been isolated from the lower airway of clinically healthy cats.6,26,27 Mycoplasmal infection has, however, been reported in association with lower airway, pulmonary parenchymal and pleural disease.

In one study of 21 cats with lower respiratory tract infections, mycoplasmas were found to be the most common cause of infection, and a Mycoplasma species was the sole isolate in the majority of those cases. 7 These organisms have been reported as the sole isolate in at least one other study of feline lower airway disease as well. 8 Mycoplasma species were recovered by culture of tracheobronchial lavage fluid in 21% of cats with pulmonary disease in one study. 6 Prevalence of mycoplasmal infection was estimated to be approximately 15% in a recent study utilizing PCR for detection in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid from cats with lower airway disease. 9 Lower airway disease, including feline asthma and chronic bronchitis, is a significant problem in cats. Based on the available data and potential for exacerbation of these conditions, evaluating for the existence of concurrent infection with Mycoplasma species is recommended.

Although uncommon, Mycoplasma species have been isolated from patients with pneumonia. In six cases, the infection was diagnosed based on pure culture of Mycoplasma species from airway wash samples.7,10 –13 An additional study diagnosed mycoplasmal infection based on PCR isolation where culture results were negative. 9 Utilization of PCR also allowed for speciation, and M felis, Mycoplasma gateae and Mycoplasma feliminutum were each documented in a single case. 9 This was the first report of M feliminutum in the feline lower airway. The significance of the particular species in the feline lower airway is still questioned. M felis is the most commonly reported mycoplasma in the feline lower respiratory tract. 7 Detection of this organism in the lower respiratory tract likely represents true infection. However, the potential for oropharyngeal contamination must also be considered, and it is essential to make every effort to reduce the likelihood of contamination during sampling and to consider culture results in combination with all other available information in each case.

Mycoplasmal infection has been occasionally documented as a cause of pulmonary abscess and pyothorax. Two cases of Mycoplasma species associated pulmonary abscess have been reported, and both cats made a full recovery after appropriate treatment.7,14 One cat was treated with a combination of surgical excision of the abscess and antimicrobial therapy, while the other cat received only antimicrobial therapy. In four cases of pyothorax associated with Mycoplasma species reported to date,15,28,29 both mixed infections (with Arcanobacterium pyogenes) 15 and pure Mycoplasma species infection have been documented. 28 These cases were thought to be due to extension of infection from other areas of the body such as the pharyngeal/oral mucosal flora or concurrent mycoplasmal bronchopneumonia.

A large number of cats diagnosed with Mycoplasma species associated lower respiratory tract disease appear to have concurrent or preceding signs of URTD. In one study, 38% of cats with lower respiratory tract infection had ocular and URTD signs. 7 Given the link between mycoplasmas and URTD, whether as a primary or secondary pathogen, the possibility of extension of infection from the upper respiratory tract must be considered. Even in the absence of URTD signs, extension of normal flora, including Mycoplasma species, could be an exacerbating factor in already compromised airways such as those affected by feline asthma and chronic bronchitis.

Sample collection

The first step towards isolating Mycoplasma species leading to a diagnosis is sample collection. Sampling methods for cats affected with URTD have included swabbing mucosal surfaces (conjunctiva, nasal passage, oropharynx), nasal flushing or collection of nasal biopsies. Samples from the lower airways are typically obtained via some form of airway wash.

Upper airway sampling

A large number of cats with URTD have concurrent conjunctivitis, and conjunctival swabs can be obtained in these cases. Alternatively, and particularly in the absence of conjunctivitis, the use of nasal or pharyngeal swabs may be considered. In one study evaluating these two sampling sites, pharyngeal swabs were comparable to nasal swabs for isolation of Mycoplasma species and appeared less stressful to the patient. 22 In a clinical setting, pharyngeal swabs may be preferable to nasal swabs as a relatively non-invasive sampling technique. Regardless of the location for obtaining the swab, care should be taken to ensure good mucosal contact with the swab as mycoplasmas adhere to host cells.

Nasal flush and biopsy have also been evaluated.16,17 These techniques would be suitable once the patient is anesthetized and intubated to provide airway protection. Both nasal flush and biopsy yield similar isolation rates for Mycoplasma species, and no qualitative difference has been identified.16,17 The fact that mycoplasmas are cell-associated organisms 2 likely accounts for the slightly increased sensitivity of isolation from nasal biopsy samples compared with nasal flush.

Lower airway sampling

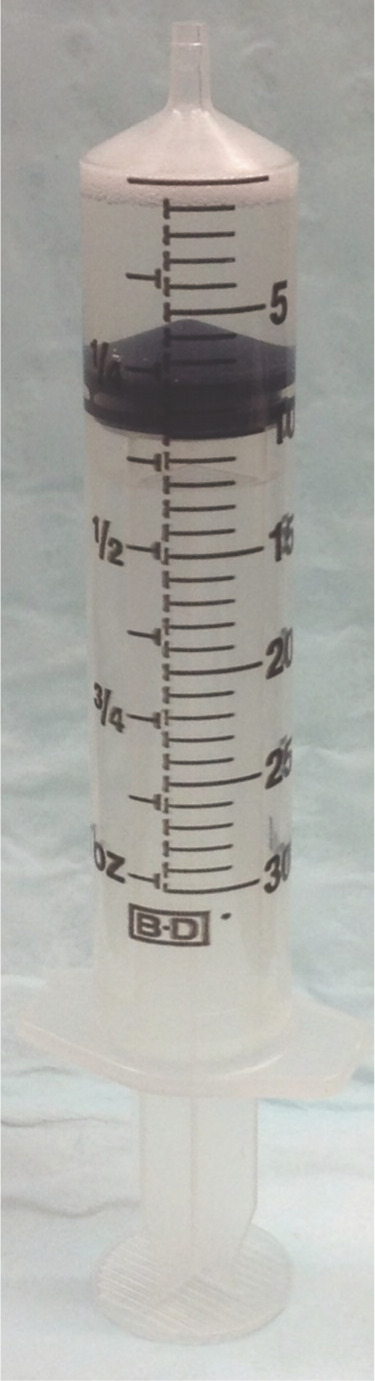

Endotracheal wash and BAL (Figure 1) are two techniques that are recommended for sampling the lower feline airways. 26 The major difference between the techniques is the level at which the wash occurs: the target for endotracheal wash is the level of the carina, while BAL aims to obtain fluid from the bronchi and alveoli (Figure 2). BAL can be performed with or without bronchoscopic guidance (Figure 3). Bronchoscopically guided BAL is recommended in the case of specific lung lobe involvement (eg, lobar pneumonia).

Figure 1.

In preparation for bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL), a syringe of sterile saline is attached to a sterile 5 Fr red rubber catheter. Note the end of the catheter has been cut using sterile scissors to create an opening at the distal end

Figure 2.

BAL fluid sample

Figure 3.

BAL being performed in a blind fashion (ie, without bronchoscopic guidance).

The patient is intubated with a sterile endotracheal tube, and a red rubber catheter is advanced through the endotracheal tube until it meets resistance and can no longer be advanced. Sterile saline is introduced through the catheter, and the airway sample is aspirated

Alternative sample collection techniques will likely be required when dealing with cases of pulmonary abscess and pyothorax. For pulmonary abscess, fine needle aspiration (FNA) of the lung nodule may provide adequate sample for culture.7,14 This sampling technique is limited by the depth of the nodule within the lung tissue. Ultrasonographic guidance can be utilized for peripheral nodules, but deeper nodules are not easily visualized with ultrasound due to air interference. 30 Computed tomography (CT) can instead be utilized for FNA of deeper lung nodules. 31 Reported complications of FNA of lung tissue are rare but include pneumothorax and hemorrhage. Complications appear higher when CT guidance is utilized, and this likely reflects sampling of deeper lesions that require penetration of aerated lung tissue. 31 Specific complications associated with FNA of pulmonary abscesses have not been reported in the veterinary literature; although the potential for inducing pyothorax should be considered, FNA is the least invasive diagnostic technique available to confirm a diagnosis of Mycoplasma species associated lung abscesses. Thoracocentesis with fluid analysis and culture is required for the diagnosis of pyothorax.

Following sampling from the patient, appropriate sample handling and transport to the laboratory must be ensured, especially when submitting for culture (see later).

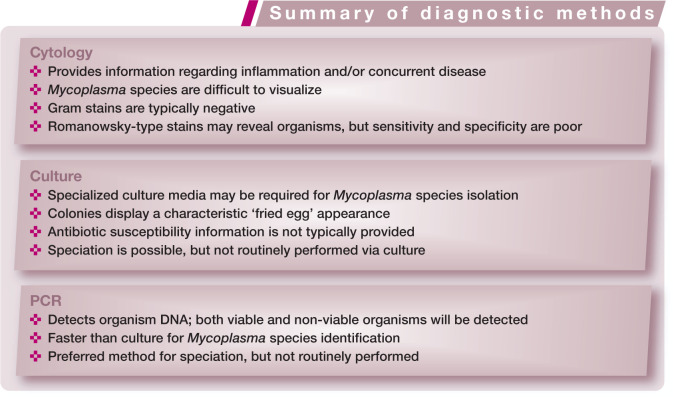

Diagnostic methods

Cytology

Due to their small size, Mycoplasma species can be difficult to visualize with light microscopy. Staining with Gram stain is unrewarding because these organisms lack a cell wall. Mycoplasma species have been visualized using Romanowsky-type stains;32 –34 however, this method can be unreliable, with poor sensitivity and specificity. 34

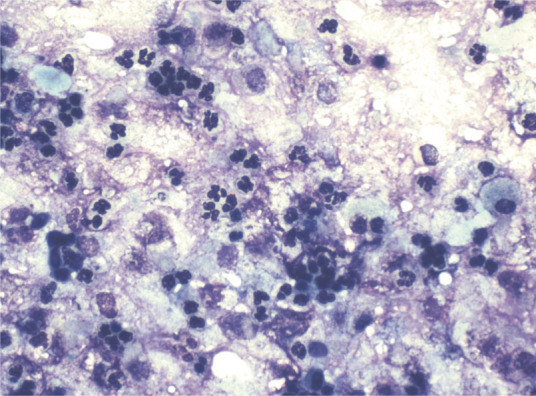

Cytologic evaluation of samples most commonly reveals predominantly neutrophilic inflammation in the absence of bacteria (Figure 4).1,2,7 While cytology provides very useful information in general, it provides no findings specific to mycoplasmal infection.

Figure 4.

Neutrophilic BAL cytology. This would be a typical finding in patients infected with Mycoplasma species. Image obtained using a × 40 objective on a light microscope. Courtesy of Peter Christopherson, Auburn University College of Veterinary Medicine

Culture

Culture can be performed on all of the sample types discussed earlier. Mycoplasmas are somewhat fragile organisms when not associated with host cells; therefore, appropriate sample handling and transport to the laboratory for culture are key. Use of special transport media (eg, Amies medium without charcoal or Stuart’s medium) should be considered, particularly if there will be a delay between sample collection and transport to the laboratory. Samples should be refrigerated if there will be any delay and shipped on ice. If this process will take longer than 24 h, some sources recommend freezing the sample and shipping on dry ice. 2 Storage and shipment recommendations can vary between microbiology laboratories and consultation with the individual laboratory is recommended.

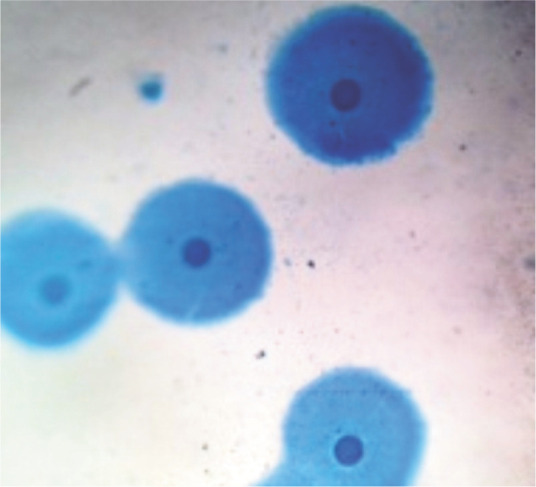

When submitting specimens for culture, the laboratory should be alerted to the suspicion of Mycoplasma species infection. Some mycoplasmas will grow on standard culture media, but often specific mycoplasma culture media is required. Some Mycoplasma species are non-cultivable even on specific culture media. Not only is there variation among Mycoplasma species in preferred media, but also in length of incubation. Some mycoplasmas will produce visible colonies in several days; for others, it may take several weeks for colonies to be visualized. This variation is one of the challenges of isolating Mycoplasma species via culture. Cultured colonies are very small and may require light microscopy for visualization; they have a characteristic ‘fried egg’ appearance (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Mycoplasmal colonies stained directly on the agar surface using Dienes’ stain. Colonies produce a characteristic ‘fried egg’ appearance. Image obtained using a × 40 objective on a light microscope. Courtesy of Terri Hathcock, Auburn University College of Veterinary Medicine Bacteriology/ Mycology Laboratory

Susceptibility testing and speciation are not routinely performed, and most laboratories report only growth of Mycoplasma species. While species determination is possible via culture, PCR is the currently the method of choice.

Polymerase chain reaction

PCR allows for detection of mycoplasmal DNA either directly from specimens or from cultured colonies. Both conventional and real-time techniques with several variations have been utilized. Some detect Mycoplasma as a genus while others are specific for certain species; PCR for M felis, for example, is currently commercially available.

Advantages of PCR include detection of small numbers of organisms and non-cultivable organisms, less concern with special transport, increased speed of detection, and ability to determine the species of Mycoplasma involved. This technique is highly sensitive, so sample or laboratory contamination can lead to false-positive results. One of the biggest disadvantages of PCR, however, is that it detects only DNA; therefore, viability of the organism, and potential clinical relevance, must be questioned. This is particularly true when an organism is detected via PCR in a patient with negative culture results. This could simply reflect the sensitivity of the assay and difficulty of Mycoplasma culture, or it could represent a non-pathogenic organism. PCR results should, therefore, always be interpreted in the light of the patient’s clinical condition.

Studies have compared PCR isolation with culture, and results reflect the increased sensitivity of PCR. Two studies evaluating PCR and culture of samples from the upper respiratory tract of cats determined that the two methods yielded similar results, with the occasional sample being PCR positive but culture negative.16,22 Evaluation of the two methods using samples of BAL fluid from cats with lower airway disease revealed less agreement, with PCR indicating a 15.4% prevalence of Mycoplasma species in a population of cats that was culture negative for Mycoplasma species. 9

In two of the above-mentioned studies, PCR allowed for species identification and revealed a couple of mycoplasmas, M feliminutum and Mycoplasma arginini, which are not typically isolated from the feline lower airway.9,16 This offers a significant advantage, especially in furthering our understanding of mycoplasmal involvement in airway disease. Clinically, speciation can also be an advantage in identifying the particular species associated with disease. Since M felis is the most commonly isolated Mycoplasma species in the feline respiratory tract, PCR assays were developed to specifically identify this organism.35,36 These appear to have good sensitivity and specificity for M felis, and provide rapid results, with one study indicating that the assay was completed within 4 h. 35

The advantages of PCR – increased sensitivity, quicker results and the ability to identify the infecting Mycoplasma species – make this an attractive option for use in the clinical setting. The main caution is the need for results to be interpreted in the light of an individual patient’s clinical presentation, since positive results do not necessarily correlate with viable organisms.

Treatment

Antimicrobial therapy is the mainstay of treatment for mycoplasmal infections. It is also important to treat any underlying disease conditions that may predispose to these infections. In the case of URTD, mycoplasmal infection might be secondary to other infections (FHV, C felis, etc) or pathology (eg, rhinitis). Therefore, successful treatment likely depends on managing the underlying disease condition. In the lower respiratory tract, Mycoplasma species are thought to be primary pathogens. However, infected cats often have concurrent conditions (bronchitis, feline asthma, etc) that could predispose to mycoplasmal infection. Strong consideration should be given to proper management of these underlying conditions where they exist.

While antimicrobial therapy based on sensitivity data is ideal for bacterial infections, this information is typically not reported by laboratories for Mycoplasma species. Therefore, empirical therapy must be chosen. These organisms are reportedly susceptible to tetracyclines, macrolides, fluoroquinolones, lincosamides, chloramphenicol and aminoglycosides. 1 Due to the lack of a cell wall, β-lactam antibiotics (penicillins, cephalosporins, etc) are not effective against Mycoplasma species.

One study compared amoxicillin–clavulanic acid, cefovecin and doxycycline for the treatment of URTD in a group of shelter cats. 37 The investigators found that amoxicillin–clavulanic acid and doxycycline were more effective than cefovecin, and also recorded a significant improvement in oculonasal discharge scores in cats receiving doxycycline. 37 They postulated that this could be attributable to the efficacy of doxcycline against Mycoplasma species. It should be noted, however, that this study did not elaborate on antimicrobial efficacy specifically in cats with mycoplasmal infections. Considering that these organisms are not susceptible to β-lactam antibiotics, the improvement seen in cats receiving amoxicillin–clavulanic acid or cefovecin was likely due to infection with a different organism.

Tetracycline, fluoroquinolone and macrolide antimicrobials are the most frequently utilized for the treatment of respiratory mycoplasmal infection in small animals. Doxycycline has demonstrated good efficacy in studies, based both on improvement of clinical signs and clearance of the organism as assessed by PCR.38,39 The duration of the doxycycline treatment course is typically recommended to be greater than 1 week. 1 Studies have demonstrated that while a 1 week course significantly reduces clinical signs, a longer duration of treatment is required to eliminate the organism based on PCR.38,39 In one study, elimination of Mycoplasma species was accomplished within approximately 19 days with doxycycline therapy; 38 however, some cats tested positive through to day 28 of therapy. All cats in this study were negative when tested again at day 42 of therapy. 38 Another study of doxycycline therapy evaluated a 7 and 14 day treatment course, and determined that, while clinical signs were well controlled after 7 days, the 14 day course produced superior elimination of the organism. However, some cats remained PCR positive for M felis after 14 days of therapy. 39

Of the fluoroquinolones, enrofloxacin is not recommended as a first choice in cats due to the risks of ocular toxicity. Newer fluoroquinolones, particularly pradofloxacin, have demonstrated efficacy and ocular safety in this species.25,38,40 Clinical signs appear to improve within 1 week of initiating pradofloxacin treatment; however, organism elimination has been documented to take approximately 20 days. 38 Azithromycin has also been used successfully to treat both upper and lower respiratory tract infections in cats, especially when Mycoplasma species are involved.7,41

It is worth emphasising again that, given that Mycoplasma species are considered normal flora of the upper respiratory tract, detection of organism DNA does not clearly correlate with URTD. Therefore, it is important to consider the individual case prior to treating for mycoplasmal infection.

Recurrence

Recurrence, or recrudescence, of infection is a concern. With upper respiratory infection, in particular, environment and exposure likely play a significant role. A large number of URTD cases occur in shelter animals where multiple factors (crowded conditions, introduction of new animals, stress, poor nutrition, etc) may make reinfection likely and compromise these animals immunologically. Additionally, concurrent infections (eg, FHV) may lay the groundwork for recurrence of Mycoplasma species infection as an opportunistic pathogen. Being part of the normal flora of the upper respiratory tract, it is highly likely that Mycoplasma species will repopulate the area. In healthy individuals in a stable, low-stress environment, this may not present as clinical illness or require treatment. It is likely also dependent on the species of Mycoplasma involved. In animals with underlying chronic pathology in the upper or lower airways, recurrence of infection may be more likely until the underlying disease condition is addressed appropriately.

The potential for recrudescence should also be considered when determining a treatment plan, in the light of evidence that inadequate length of therapy can be detrimental to elimination of these organisms.

Prevention

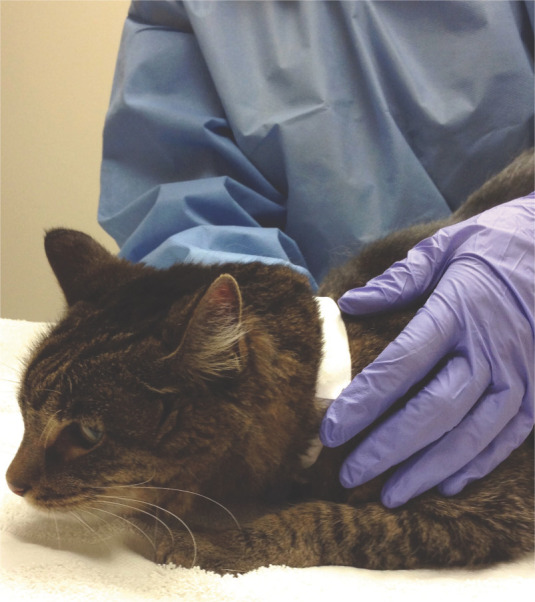

Prevention of mycoplasmal infection relies on prevention of concurrent infections and/or management of underlying disease conditions that predispose to opportunistic infection. In shelter situations, efforts should be made to avoid overcrowding, reduce stress and reduce concurrent infections. Hand washing between handling individual animals, and wearing gloves and gowns when handling animals with clinical signs of respiratory disease (Figure 6), may help reduce spread in these environments. Although isolation of animals with signs of respiratory disease would be ideal, this can be extremely difficult in a shelter environment. Routine disinfectants should be adequate to eliminate the organism from the environment.

Figure 6.

Wearing gloves and gowns when handling animals with URTD signs, and hand washing between individual animals, may help reduce spread of mycoplasmal infection

A feline vaccine against Mycoplasma species is not currently available.

Key Points

It is clinically challenging to determine the role of Mycoplasma species in feline upper respiratory tract disease.

Mycoplasma species have only been isolated from the lower respiratory tract of cats with respiratory disease, and this supports a role for this organism as a primary pathogen in the lower respiratory tract.

Culture for Mycoplasma species may be optimized with special media. Therefore, it is important to communicate suspicions of Mycoplasma infection to the laboratory at the time of sample submission.

Advantages of PCR include increased sensitivity, faster results, and the ability to identify which Mycoplasma species is involved in an infection.

Antimicrobial therapy is the mainstay of treatment for Mycoplasma species infection; however, infection may recur. Management of concurrent disease conditions also plays an important role in determining the success of treatment.

Footnotes

Funding: The author received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors for the preparation of this article.

The author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- 1. Greene CE, Chalker VJ. Nonhemotropic mycoplasmal, ureaplasmal, and L-form infections. In: Greene CE. (ed). Infectious diseases of the dog and cat. 4th ed. St Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders, 2012, pp 319–325. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sykes JE. Mycoplasma infections. In: Sykes JE. (ed). Canine and feline infectious diseases. St Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders, 2014, pp 382–389. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Campbell LH, Snyder SB, Reed C, Fox JG. Mycoplasma felis-associated conjunctivitis in cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1973; 163: 991–995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tan RJ. Suceptibility of kittens to Mycoplasma felis infection. Jpn J Exp Med 1974; 44: 235–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Haesebrouck F, Devriese LA, van Rijssen B, Cox E. Incidence and significance of isolation of Mycoplasma felis from conjunctival swabs of cats. Vet Microbiol 1991; 26: 95–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Randolph JF, Moise NS, Scarlett JM, Shin SJ, Blue JT, Corbett JR. Prevalence of mycoplasmal and ureaplasmal recovery from tracheobronchial lavages and of mycoplasmal recovery from pharyngeal swab specimens in cats with or without pulmonary disease. Am J Vet Res 1993; 54: 897–900. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Foster SF, Martin P, Allan GS, Barrs VR, Malik R. Lower respiratory tract infections in cats: 21 cases (1995. –2000). J Feline Med Surg 2004; 6: 167–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chandler JC, Lappin MR. Mycoplasmal respiratory infections in small animals: 17 cases (1988–1999). J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2002; 38: 111–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Reed N, Simpson K, Ayling R, Nicholas R, Gunn-Moore D. Mycoplasma species in cats with lower airway disease: improved detection and species identification using a polymerase chain reaction assay. J Feline Med Surg 2012; 14: 833–840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Foster SF, Barrs VR, Martin P, Malik R. Pneumonia associated with Mycoplasma spp in three cats. Aust Vet J 1998; 76: 460–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Trow AV, Rozanski EA, Tidwell AS. Primary mycoplasma pneumonia associated with reversible respiratory failure in a cat. J Feline Med Surg 2008; 10: 398–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bongrand Y, Blais MC, Alexander K. Atypical pneumonia associated with a Mycoplasma isolate in a kitten. Can Vet J 2012; 53: 1109–1113. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Barrs VR, Allan GS, Martin P, Beatty JA, Malik R. Feline pyothorax: a retrospective study of 27 cases in Australia. J Feline Med Surg 2005; 7: 211–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Crisp MS, Birchard SJ, Lawrence AE, Fingeroth J. Pulmonary abscess caused by a Mycoplasma sp in a cat. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1987; 191: 340–342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gulbahar MY, Gurturk K. Pyothorax associated with a Mycoplasma sp and Arcano-bacterium pyogenes in a kitten. Aust Vet J 2002; 80: 344–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Johnson LR, Drazenovich NL, Foley JE. A comparison of routine culture with polymerase chain reaction technology for the detection of Mycoplasma species in feline nasal samples. J Vet Diagn Invest 2004; 16: 347–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Johnson LR, Kass PH. Effect of sample collection methodology on nasal culture results in cats. J Feline Med Surg 2009; 11: 645–649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Holst BS, Hanas S, Berndtsson LT, Hansson I, Söderlund R, Aspán A, et al. Infectious causes for feline upper respiratory tract disease – a case-control study. J Feline Med Surg 2010; 12: 783–789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gourkow N, Lawson JH, Hamon SC, Phillips CJ. Descriptive epidemiology of upper respiratory disease and associated risk factors in cats in an animal shelter in coastal western Canada. Can Vet J 2013; 54: 132–138. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Blackmore DK, Hill A. The experimental transmission of various mycoplasmas of feline origin to domestic cats (Felis catus). J Small Anim Pract 1973; 14: 7–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bannasch MJ, Foley JE. Epidemiologic evaluation of multiple respiratory pathogens in cats in animal shelters. J Feline Med Surg 2005; 7: 109–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Veir JK, Ruch-Gallie R, Spindel ME, Lappin MR. Prevalence of selected infectious organisms and comparison of two anatomic sampling sites in shelter cats with upper respiratory tract disease. J Feline Med Surg 2008; 10: 551–557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Johnson LR, Foley JE, De Cock HE, Clarke HE, Maggs DJ. Assessment of infectious organisms associated with chronic rhinosinusitis in cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2005; 227: 579–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hartmann AD, Hawley J, Werckenthin C, Lappin MR, Hartmann K. Detection of bacterial and viral organisms from the conjunctiva of cats with conjunctivitis and upper respiratory tract disease. J Feline Med Surg 2010; 12: 775–782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Spindel ME, Veir JK, Radecki SV, Lappin MR. Evaluation of pradofloxacin for the treatment of feline rhinitis. J Feline Med Surg 2008; 10: 472–479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lee-Fowler T, Reinero C. Bacterial respiratory infections. In: Greene CE. (ed). Infectious diseases of the dog and cat. 4th ed. St Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders, 2012, pp 936–950. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Padrid PA, Feldman BF, Funk K, Samitz EM, Reil D, Cross CE. Cytologic, microbiologic, and biochemical analysis of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid obtained from 24 healthy cats. Am J Vet Res 1991; 52: 1300–1307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Malik R, Love DN, Hunt GB, Canfield PJ, Taylor V. Pyothorax associated with a Mycoplasma species in a kitten. J Small Anim Pract 1991; 32: 31–34. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wong WT, Noor F. Pyothorax in the cat – a report of two cases. Kajian Vet 1984; 16: 15–17. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Reichle JK, Wisner ER. Non-cardiac thoracic ultrasound in 75 feline and canine patients. Vet Radiol Ultrasound 2000; 41: 154–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zekas LJ, Crawford JT, O’Brien RT. Computed tomography-guided fine-needle aspirate and tissue-core biopsy of intrathoracic lesions in thirty dogs and cats. Vet Radiol Ultrasound 2005; 46: 200–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Foster SF, Martin P. Lower respiratory tract infections in cats: reaching beyond empirical therapy. J Feline Med Surg 2011; 13: 313–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Johnsrude JD, Christopher MM, Lung NP, Brown MB. Isolation of Mycoplasma felis from a serval (Felis serval) with severe respiratory disease. J Wildl Dis 1996; 32: 691–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hillstrom A, Tvedten H, Kallberg M, Hanas S, Lindhe A, Holst BS. Evaluation of cytologic findings in feline conjunctivitis. Vet Clin Pathol 2012; 41: 283–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chalker VJ, Owen WM, Paterson CJ, Brownlie J. Development of a polymerase chain reaction for the detection of Mycoplasma felis in domestic cats. Vet Microbiol 2004; 100: 77–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Soderlund R, Bolske G, Holst BS, Aspan A. Development and evaluation of a real-time polymerase chain reaction method for the detection of Mycoplasma felis. J Vet Diagn Invest 2011; 23: 890–893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Litster AL, Wu CC, Constable PD. Comparison of the efficacy of amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, cefovecin, and doxycycline in the treatment of upper respiratory tract disease in cats housed in an animal shelter. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2012; 241: 218–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hartmann AD, Helps CR, Lappin MR, Werckenthin C, Hartmann K. Efficacy of pradofloxacin in cats with feline upper respiratory tract disease due to Chlamydophila felis or Mycoplasma infections. J Vet Intern Med 2008; 22: 44–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kompare B, Litster AL, Leutenegger CM, Weng HY. Randomized masked controlled clinical trial to compare 7-day and 14-day course length of doxycycline in the treatment of Mycoplasma felis infection in shelter cats. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis 2013; 36: 129–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lees P, Toutain PL. Pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, metabolism, toxicology and residues of phenylbutazone in humans and horses. Vet J 2013; 196: 294–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ruch-Gallie RA, Veir JK, Spindel ME, Lappin MR. Efficacy of amoxycillin and azithromycin for the empirical treatment of shelter cats with suspected bacterial upper respiratory infections. J Feline Med Surg 2008; 10: 542–550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]