Abstract

Practical relevance:

Many pet cats are kept indoors for a variety of reasons (eg, safety, health, avoidance of wildlife predation) in conditions that are perhaps the least natural to them. Indoor housing has been associated with health issues, such as chronic lower urinary tract signs, and development of problem behaviors, which can cause weakening of the human–animal bond and lead to euthanasia of the cat. Environmental enrichment may mitigate the effects of these problems and one approach is to take advantage of cats’ natural instinct to work for their food.

Aim:

In this article we aim to equip veterinary professionals with the tools to assist clients in the use of food puzzles for their cats as a way to support feline physical health and emotional wellbeing. We outline different types of food puzzles, and explain how to introduce them to cats and how to troubleshoot challenges with their use.

Evidence base:

The effect of food puzzles on cats is a relatively new area of study, so as well as reviewing the existing empirical evidence, we provide case studies from our veterinary and behavioral practices showing health and behavioral benefits resulting from their use.

Introduction

Although cats are currently the most commonly kept pet in the USA, the conditions they are kept in are perhaps the least natural to them, especially given that the domestic cat’s behavior and behavioral needs are very similar to those of their closest wild ancestor, the African wildcat. 1 Current veterinary and cat care guidelines (eg, American Veterinary Medical Association; Indoor Pet Initiative) encourage keeping cats indoors for safety, health and ecological reasons, but this recommendation, along with the concurrent misperception of cats as being low-maintenance pets, means that many cats are housed in suboptimal environments. One significant influence on cats’ living conditions is how they are routinely fed. Most cats are offered food ad libitum from a bowl, are often required to share feeding areas or dishes with other cats and have to expend little to no effort to acquire calories.

Cats are natural predators that, in the wild, tend to eat multiple small meals each day.2,3 When able to hunt, cats make several hunting attempts each day, only approximately half of which lead to a prey item. 4 Indoor housing has been associated with increases in the occurrence of obesity,5–7 type 2 diabetes mellitus, 8 joint problems 9 and chronic lower urinary tract signs. 10 Furthermore, the risk of behavioral and mental health problems may increase with confinement. 11 Commonly reported behavioral concerns from cat owners include aggression, attention-seeking behaviors and stress-related behaviors such as house-soiling and overgrooming.12,13 These problem behaviors can lead to a weakening of the human–animal bond, and in many cases result in unwarranted euthanasia of the cat.14,15 Environmental enrichment may have some mitigating effects on these stress-related behaviors. 16

We propose that one approach to environmental enrichment is to take advantage of cats’ natural instinct to work for their food. In this review, we explain what food puzzles are and why they are a biologically relevant enrichment device for cats. We provide an overview of the most common types of food puzzles, how they should be used and how to overcome any client resistance to changing the method of food delivery to their cats. Finally, we provide tools for assessing the most appropriate types of food puzzles for individual cats, and a user-friendly handout that practitioners can give to their clients to get them started.

What are food puzzles?

Food puzzles were originally created to provide enrichment for captive zoo and laboratory animals. 17 They typically consist of any object that can hold food and be manipulated to release food when the animal interacts with it. Food puzzles may be mobile (rolled or pushed) or stationary, and they can be used to provide either wet or dry food. They may be purchased or homemade (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Homemade mobile (a), homemade stationary (b), purchased stationary (c) and purchased mobile (d) food puzzles. Courtesy of Mikel Delgado (a,c), Leticia Dantas (b) and Ingrid Johnson (d)

Mobile food puzzles are often shaped like a ball, egg or tube. Their rounded surfaces make it easy for cats to roll the puzzle by pushing with a paw or their nose. These puzzles generally have one or more holes in them, and in some cases can be adjusted to make release of food easier or harder by changing the size or number of open spaces that can dispense food. The current iterations of these puzzles are typically designed for use with dry food or treats.

Stationary puzzles tend to be larger, with sturdy bases, and holes, cups or channels. Dry food can be placed in the holes and cups, which must be fished out with a paw. Wells may be filled with wet food; the cat must lick food out of these wells, mimicking how cats use their jaw muscles to remove flesh from bone.

Homemade puzzles for dry food can be made easily by cutting holes in containers such as yogurt pots, toilet paper rolls, egg cartons, margarine tubs or water bottles. Ice cube trays or muffin pans can be used for wet food, and yogurt lids can be placed over the individual reservoirs or cups to increase difficulty.

Benefits of using food puzzles

Zoos and sanctuaries encounter many obstacles to providing adequate housing for felid species, which may have difficulty adjusting to captivity for several reasons. Territory and hunting opportunities are restricted, and many solitary species are housed in pairs or in groups. 18 The parallels with domestic cat housing are numerous. Implementing enrichment by providing foraging opportunities and food puzzles offers several benefits to captive large cats, including reducing stereotypies such as pacing,19,20 improving body condition 21 and increasing exploratory behavior.18,22

Current guidelines for the care and welfare of domestic cats suggest that they be allowed to express the predatory sequence to the extent possible, including active acquisition of food.4,23,24 Although few empirical studies of the benefits of food puzzles for companion animals have been conducted, provision of food puzzles has been shown to increase activity and reduce problematic behavior in dogs. 25 In cats, various forms of enrichment (such as play, perches, play towers and novel toys) have been shown to reduce signs of stress 16 and to contribute to weight loss. 26 Table 1 outlines cases from our veterinary and behavioral practices that showed either behavioral or health-related benefits after the implementation of food puzzles along with other forms of behavior modification. Benefits we have observed include weight loss, decreased aggression toward humans and other cats, reduced anxiety and fear, cessation of attention-seeking behaviors and resolution of litter box avoidance.

Table 1.

Case examples where food puzzles were implemented to aid with a health or behavioral concern

| Cat(s) | Presenting concern(s) | Food puzzle(s) implemented | Other modifications implemented | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DMH; 2 x MN; 11 y and 6 y | Obesity | Mobile and stationary (purchased) | – | Older cat lost 6.4% of body weight in 3.5 months, and increased mobility. Younger cat lost 11% of body weight in 12 months |

| DMH; SF; 9 y | Obesity | Mobile (homemade and purchased) | – | Weight loss: 11% in 12 months |

| DSH; NM; 8 y | Obesity | Mobile (homemade and purchased) | – | Weight loss: 20% in 12 months |

| DSH; 2 x MN; 7 y and 1 y | Younger cat trying to play rough with older cat | Mobile and stationary (purchased) | A general enrichment plan and clicker training were also introduced | Cats played with food puzzles simultaneously; older cat preferred stationary puzzles and younger cat preferred rolling puzzles. The altercations between cats decreased significantly |

| DMH; 2 x NM; 3.5 y | Sibling cats meowing for food; waking owner up to be fed; interfering with owner’s preparation and eating of meals; stealing food from plates, sinks and counters | Mobile and stationary (homemade and purchased) | Owner was instructed to avoid leaving food and dirty dishes on counters and sinks to prevent cats from being inadvertently rewarded for undesirable behaviors | Food puzzles slowed down both cats’ eating and a decrease in meowing for food was observed. Behavior around owner’s preparation of food and while eating was improved as long as cats were distracted with a food puzzle |

| British Shorthair; NM; 3 y | Impulsive and frustrationbased aggression towards owner (biting with no warning when anticipating meals, and when attention was not given) | Mobile (purchased) and stationary (homemade) | – | The use of puzzles immediately resolved the situations where the cat experienced frustration (anticipation of meals, attention-seeking) and the cat started to show appeasement behaviors as opposed to impulsively attacking. The aggressive behavior resolved within 6 months |

| DSH; NM; 10 y | Disorientation, nocturnal vocalization, alterations in the sleep–wake cycle, decreased social interactions; diagnosed with cognitive dysfunction syndrome | Mobile and stationary (homemade and purchased) | – | Introduction of puzzles associated with marked decrease in disorientation, improved sleep–wake cycle and cessation of nocturnal vocalizations, as well as increased social behavior between the cat and other cats in the household (3 x NM and 1 x SF in total) and the clients. Provision of enrichment avoided introduction of pharmacological treatment |

| DSH; SF; 8 y | Fear-based aggression toward owner (cat signaled fear when approached, showed severe avoidance behavior and bit if touched or picked up) | Mobile and stationary (purchased) | In addition to the puzzles provided, the client was instructed to desensitize and countercondition the cat to the owner’s approach, and to positively reinforce alternative behaviors | The cat’s fear-related aggressive behaviors gradually decreased in frequency and intensity over time. After 1 year of treatment, the client was able to pet and pick up the cat, and the cat came when called. No more episodes of aggression were reported |

| DSH; NM; 9 y | Noise phobia (cat had fear and panic reactions to several types of sudden and loud noises, sometimes redirecting aggression to a nearby cat in the multi-cat household) | Mobile and stationary (purchased) | – | Redirected aggression resolved. Signs of noise phobia significantly improved |

| DSH; NM; 2 y | Fear of people (familiar and unfamiliar) | Mobile and stationary (purchased) | – | Behavior significantly improved, with cat showing attachment signs to both owners, coming when called, allowing (and being relaxed during) petting; avoidance behavior ceased |

| DSH; 1 SF and 1 NM; 8 y and 2 y | Fear-based aggressive behavior (older toward younger cat); younger cat redirected aggression toward the older cat. Altercations frequently led to bites | Mobile and stationary (purchased) | – | Intensity and frequency of aggression decreased and no more bites occurred. Both cats started to use avoidance behavior rather than aggression. The younger cat stopped redirecting aggression toward the older cat |

| DSH; 2 x SF; 10 y and 8 y | Fear-based aggressive behavior toward cat housemate (younger cat would signal fear and attack the older cat whenever it approached) | Mobile and stationary (purchased). Puzzles were provided for both cats, which were temporarily separated | Desensitization and counterconditioning therapy was implemented with the use of the rolling puzzles and during feeding sessions of highly palatable food | Fear signaling (hissing, avoidance) was still seen sporadically, but no episodes of offensive aggression were reported after 6 months of treatment |

| DSH; NM; 7 m | Pouncing and stalking the clients’ guinea pigs | Mobile and stationary (homemade) | Counterconditioning therapy sessions toward the guinea pigs | Implementation of puzzles, and desensitization and counterconditioning therapy sessions toward the guinea pigs resulted in cessation of the cat’s behaviors toward them |

| DLH; NM; 12 y | Urination outside of litter box due to chronic feline idiopathic cystitis | Mobile and stationary (purchased) | Besides the food puzzles, appropriate litter box management was recommended | Behavior completely resolved within 6 months of treatment |

| DLH; MN; 1 y | Anxiety signs when left alone (increased vocalizations, agitation, pacing), hyperattachment (followed owner constantly, stress signs when owner was out of sight) and anxiety response (agitation and tension) to owner departure cues. Diagnosed with separation anxiety syndrome | Mobile and stationary (homemade and purchased) | A comprehensive enrichment plan was formulated for this cat, with the addition of a more complex environment (vertical space and hiding areas) | Anxiety signs while the client was away completely stopped. Signs of hyperattachment and anxiety responses to owner departure cues were still seen but gradually waned within 1 year of treatment |

| DLH; SF; 9 y | Signs of depression when left alone by the owner (anorexia, social withdrawal, lack of play behavior), hyperattachment (following owner constantly, stress signs when owner was out of sight) and anxiety response to owner departure cues (agitation and tension). Diagnosed with separation anxiety syndrome | Mobile and stationary (homemade and purchased) | A comprehensive enrichment plan was formulated for this cat, with the addition of a more complex environment (vertical and hiding areas). A safe place was also conditioned | Signs of depression while the owner was away and of hyperattachment and anxiety responses to owner departure cues decreased in frequency with gradual improvement during 6 months. Within 1 year, the owner ranked the cat’s improvement as excellent (signs were mild or not seen) |

| Varied; 2 x SF and 3 x NM; varied ages | Multi-cat household, meal-related fighting and urine marking. Urine marking continued, despite the cats living in separate spaces owing to fighting. Regurgitation of undigested food was observed during meals | Mobile and stationary (homemade and purchased) | Cats were gradually reintroduced using positive reinforcement and counterconditioning techniques. A litter box cafeteria was offered, allowing the cats to choose their preference. Thereafter, permanent litter boxes were added in previously soiled areas of the home. Scratching posts were placed in areas where litter boxes were not an option, providing alternative marking opportunities. Meal feeding ceased and canned food was offered in excess in multiple feeding stations. Interactive play at a minimum of once a day was recommended and implemented | Significant decrease in inter-cat aggression, urine marking ceased, cats were fully integrated and no longer required separation. Regurgitation due to overeating much reduced in frequency |

| DSH; SF; 6 m | Urination outside of the litter box, urinating in bathtub daily | Mobile (purchased). Owners began leaving food puzzles in the bathtub for the cat to play with | Owners made simultaneous adjustments to the litter box that increased compliance | Cat stopped urinating outside of the litter box |

| Persian; SF; 6 y | Urination outside of litter box, diagnosed with feline idiopathic cystitis or Pandora syndrome | Mobile and stationary (purchased) | After initial buprenorphine treatment for the acute presentation, a comprehensive plan of multimodal environmental modification was implemented | Cat has been in remission for 2.5 years |

| DSH; MN; 11 y | Urine marking (cat lived in a multi-cat household and had episodes throughout its adult life) | Mobile and stationary (purchased) | Vertical space and hiding places were also added to the house | Marking behavior ceased |

| DSH; SF; 9 y | Urination outside of litter box due to chronic feline idiopathic cystitis, possible location and substrate preference for toileting behavior and litter box aversion | Mobile and stationary (purchased) | In addition to the food puzzles, appropriate litter box management was recommended | Behavior completely resolved within 3 months of treatment |

| DSH; NM; 2 y | Urination outside of litter box due to chronic feline idiopathic cystitis, possible location and substrate preference for toileting behavior and litter box aversion | Mobile and stationary (purchased) | Besides the food puzzles, appropriate litter box management was recommended | Behavior completely resolved within 3 months of treatment |

| Maine Coon; NM; 8 m | Pronounced fear toward household dog (13-week-old Golden Retriever); mild inappropriate play behavior toward owners and stress-induced scratching | Mobile and stationary (purchased) | Safe place conditioning and desensitization and counterconditioning to dog, plus additional physical enrichment in the house | All problem behaviors resolved |

| DMH; SF; 16 y | Obesity, lack of interaction with owners, secluded itself in one room. Fearful and antisocial with new kittens in home despite positive slow introduction | Started with stationary and advanced to all types | Many other accommodations had already been implemented for this cat (vertical space, hiding places, heating pads, canned and dry food, attempts to engage in interactive play and supportive therapy for arthritis) with little to no change | Weight loss: 32% in 18 months. After implementing stationary food puzzles the cat started to lose weight and play with the owners more. It became interested in the other foraging toys outside of ‘its room’ that the kittens were playing with. It eventually rejoined the household, using both stationary and mobile toys. It will now forage side by side with the young cats |

DMH = domestic mediumhair; NM = neutered male; SF = spayed female; DSH = domestic shorthair; DLH = domestic longhair; y = years; m = months

Furthermore, implementing food puzzles presents few risks of decreasing the welfare of cats. In one study, 85% of group-housed cats (23/27) in a shelter engaged with a food puzzle without increases in aggression between cats, 27 suggesting few problems with implementing food puzzles in multi-cat environments. Although problem-solving to acquire food may initially frustrate some animals, presenting animals with some level of challenge that is appropriate to their natural ecology and matched to their skill level is likely to provide cognitive, physical and behavioral benefits in otherwise-enriched surroundings. 28

Implementing food puzzles

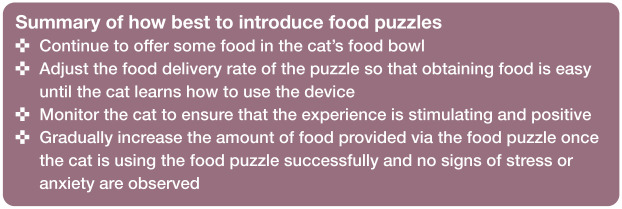

As with the introduction of any new resource, successfully implementing food puzzles requires some planning. Clients should be prepared to try a few different types of food puzzle, because cats may have individual preferences for the type of puzzle or how they interact with puzzles (eg, some cats prefer mobile puzzles that can be pushed or rolled, while others are more adept at using stationary puzzles; some cats are more likely to use their paws to move a toy, while others may push the toy with their nose). The box below provides a guide to helping clients choose a starter puzzle.

Ultimately, because implementing food puzzles offers enrichment beyond just as a means of providing food, the end goal is to have several different types of puzzles available for cats (as is recommended with other toys). The key to success is for clients to introduce puzzles to the cats correctly. This means setting the difficulty level to meet the abilities of the cat, and increasing the cat’s motivation to interact with the puzzle as much as possible. Some pointers for clients on how best to introduce food puzzles are given in the box above. Clients should be encouraged to convey feedback to the practice staff on the cat’s progress.

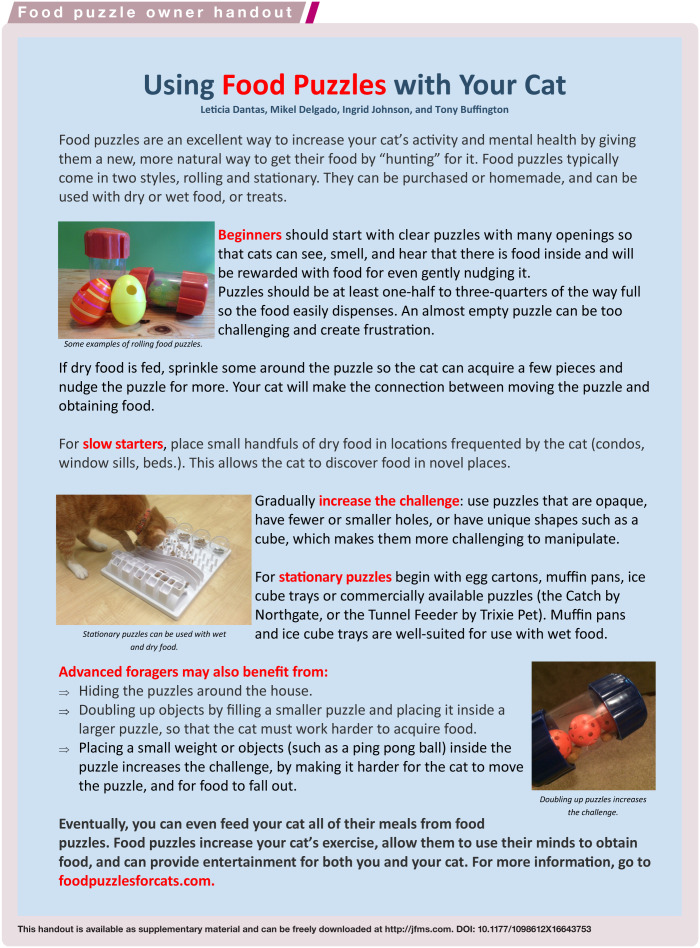

Initially, obtaining food from the puzzle needs to be as easy as obtaining food from the food bowl. This means that the cat should have to do very little work for food at first. The puzzle should be filled as much as possible, and should have several large holes to allow food to fall out easily. The puzzle should roll with little manipulation. For stationary puzzles, cups or reservoirs should be overflowing (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

(a,b) Puzzles should initially be filled as much as possible. Photos courtesy of Mikel Delgado

As cats may initially be resistant to working for food, particularly if they have a history of not having to do so,29,30 the regular food dish may need to be removed when introducing food puzzles. Because some cats may view their food container as a ‘safety signal’, or may be stressed by changes in their environment, they may prefer having the puzzle initially introduced as a choice next to the usual feeding container at the time of feeding, and containing the cat’s usual food. Some cats, particularly those that tend to be nervous, may prefer that the food puzzle be placed in a quiet area, where they can explore it undisturbed.

The food puzzle should be introduced when the cat is likely to be hungry. Motivation may be increased at first by using a novel food type in the puzzle, such as treats or a dental diet. As the cat becomes more adept at using the puzzle, the food can be changed to their regular diet, or a mix of their regular dry food and treats.

For dry food puzzles, the client should place food on the floor next to and around the puzzle and allow the cat to eat around the puzzle. Their cat may inadvertently move the puzzle while eating, which will help them make the association between moving the puzzle and receiving food. The owner may even gently roll or nudge the puzzle at first to maintain the cat’s interest. Eventually, regular food dishes can be removed and the cat can receive all of its daily food from puzzles.

Troubleshooting potential challenges and solutions

Some clients (and cats) may be reluctant to accept the introduction of food puzzles. Making food puzzles as user friendly and convenient as possible increases the client’s likelihood of using them, and, consequently, improves their cat’s welfare. Our collective experience is that most, if not all, cats can adjust to food puzzles, given time, patience and proper staging of difficulty. Some common challenges to food puzzle use and how we address them in our veterinary and behavioral practices are discussed below.

The owner does not think their cat will use food puzzles

We have not encountered cats that could not adapt to food puzzles. Senior cats, kittens, three-legged cats, blind cats and cats with other disabilities, such as partial paralysis, have all been observed to use a food puzzle of some type. Reminding the client of the cat’s natural lifestyle as a hunter that works for food may be helpful. Sharing and discussing the food puzzle handout (see page 728) with the client, as well as demonstrating how the puzzles work, will help clients get started. Providing coaching and encouragement during the implementation process reduces the likelihood of the client concluding that their cat is unwilling or unable to work for their food.

The owner will not make or purchase food puzzles

The best way to address this is to have food puzzles available for sale in the veterinary practice, or to provide referrals to local pet stores that sell food puzzles. There are also many good resources online describing how to create food puzzles out of recyclable materials (such as yogurt containers and plastic water bottles).

The owner does not want to prepare food puzzles daily

If the client is willing, they can acquire several food puzzles to rotate. All dry food puzzles can be prepared once a week and stored in airtight storage bins. 31

The owner is concerned about noise/ night-time activity

Stationary puzzles can be used at night, or mobile food puzzles can be confined to areas away from the bedroom.

The owner is resistant to having food scattered around the home

The cat will likely eat most of the food dispensed by the puzzle. However, food puzzles can be used in select rooms (eg, bathroom, office, kitchen), or in more restricted areas such as bathtubs, laundry baskets, under- the-bed storage containers or in the lids of large storage totes. The downside of restricting the area the puzzle is used in is that it makes food easier to obtain, and reduces the cat’s movement and activity; and bathtubs and containers may provide other challenges for any cat with a mobility issue (such as older, arthritic cats).

The owner has tried a food puzzle and the cat would not use it

The owner should be encouraged to try again, this time empowered with more detailed instructions and specific guidance. Staff should be trained to guide clients through learning challenges. Initial difficulty of use and lack of motivation are two of the most common barriers to cats’ willingness to use food puzzles. For slow starters, placing handfuls of dry food in locations frequented by the cat (cat furniture, window sills, beds) allows the cat the chance to discover food in novel places. These cats generally can transition from this to stationary puzzles located in these areas.

There are multiple cats in the home

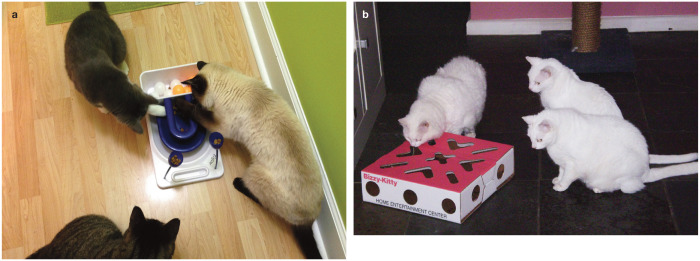

All cats in the home can be acclimated to food puzzles. Because cats may have individual preferences, several types of food puzzles can be distributed throughout the home, and each cat should be provided with their own puzzle. If one type of puzzle is more popular, then the owner should provide multiple puzzles of that type. This prevents cats from having to compete over food resources, and from being forced to eat in the same area, a behavior that is unnatural to solitary hunters. However, some cats are willing to use a food puzzle together (Figure 3). 27

Figure 3.

(a,b) Some cats will use food puzzles together. Courtesy of Ingrid Johnson (a) and Leticia Dantas (b)

There are dogs in the home

For homes with dogs, puzzles can be used in restricted areas (see earlier), or baby gates can be used to keep dogs out of certain areas of the home where the cats’ food puzzles are kept. The baby gates should be placed at a height whereby the cat can either jump over or crawl under, but the dog cannot. Dogs also can be taught a ‘leave it’ verbal cue, and be provided with their own foraging toys in a separate area of the house, or, if possible, outdoors.

The cat appears frustrated by the food puzzle

Frustration can occur in animals when a previously obtainable resource changes or becomes inaccessible. Frustration may have adaptive properties, as it can lead to the persistence of efforts and emitting of novel behaviors to access a resource or solve a problem.28,32 While such behaviors would promote successful use of food puzzles, frustration may lead to development of fearful or aggressive behaviors in some animals, particularly when a problem is insoluble. 33 We have not encountered cats that developed such negative behaviors after the introduction of food puzzles, because difficulty was staged appropriately. We recognize that frustration is possible, particularly in unenriched environments. We recommend that food puzzles be introduced as part of a multimodal enrichment plan,34,35 and that our implementation recommendations be followed carefully.

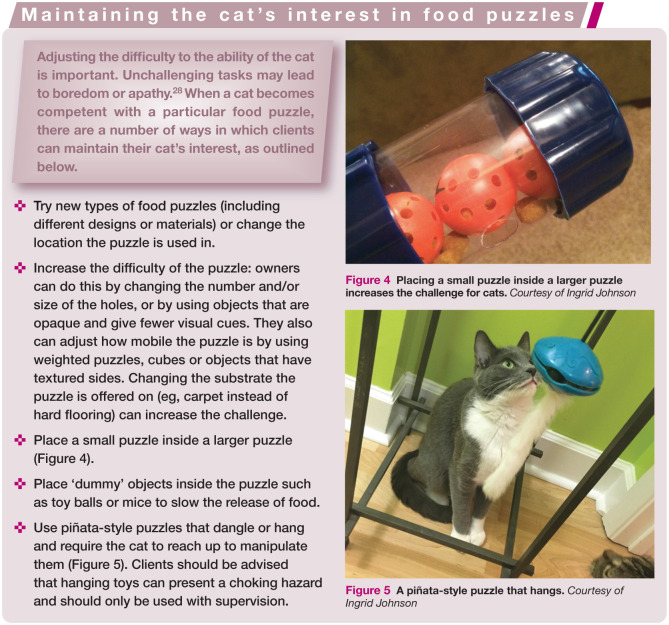

Figure 4.

Placing a small puzzle inside a larger puzzle increases the challenge for cats. Courtesy of Ingrid Johnson

Figure 5.

A piñata-style puzzle that hangs. Courtesy of Ingrid Johnson

Limitations and further research

In this review, we have not included details of all cases seen that have involved recommendations for the use of food puzzles. Rather, we have attempted to provide a range of the types of cases that might be commonly encountered in primary care veterinary practice. We acknowledge there are limitations to the cases we have provided. They are retrospective in nature, and, in some instances, food puzzles were not the only intervention, so one cannot be sure of the relative effectiveness of each component of the treatment.

We included these cases acknowledging that this limitation is also often found in primary care medicine. Further research is greatly needed to determine the relative effectiveness of different approaches to environmental enrichment, including food puzzles, in promoting health and welfare for confined cats.

Key points

Food puzzles enable cat owners to take advantage of the domestic cat’s natural inclination to work (hunt) for their food to provide mental stimulation and increase the activity of their pet cats.

Food puzzles are relatively easy to implement, and there are few risks associated with their use.

There are likely many health and behavioral benefits from using food puzzles. Examples of the potential benefits of their use in concert with other behavior modifications are outlined in the retrospective case studies in Table 1.

Veterinary practices are often the main source of information for many pet owners, and this review provides suggestions, tools and user-friendly information to help veterinary professionals make the recommendation of food puzzles a standard practice.

Supplemental Material

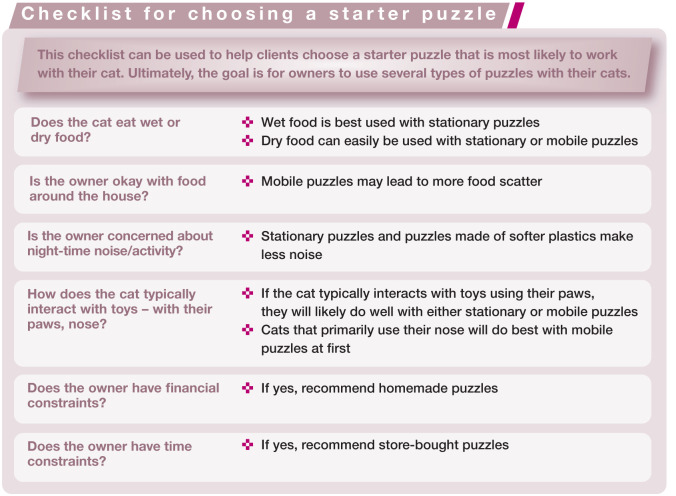

Using food puzzles with your cat

Footnotes

Funding: MMD was supported by an NSF GRFP fellowship.

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Rodan I, Heath S. Feline behavioral health and welfare. St Louis, MO: Elsevier Health Sciences, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Beaver BV. Feline behavior. St Louis, MO: Elsevier Health Sciences, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 3. National Research Council (US). Ad Hoc Committee on Dog and Cat Nutrition. Nutrient requirements of dogs and cats. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rochlitz I. A review of the housing requirements of domestic cats (Felis silvestris catus) kept in the home. Appl Anim Behav Sci 2005; 93: 97–109. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Allan F, Pfeiffer D, Jones B, et al. A cross-sectional study of risk factors for obesity in cats in New Zealand. Prev Vet Med 2000; 46: 183–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Robertson I. The influence of diet and other factors on owner perceived obesity in privately owned cats from metropolitan Perth, Western Australia. Prev Vet Med 1999; 40: 75–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Scarlett J, Donoghue S, Saidla J, et al. Overweight cats: prevalence and risk factors. J Int Assoc Stud Obes 1994; 18: S22–S28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Slingerland LI, Fazilova VV, Plantinga EA, et al. Indoor confinement and physical inactivity rather than the proportion of dry food are risk factors in the development of feline type 2 diabetes mellitus. Vet J 2009; 179: 247–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Laflamme DP. Understanding and managing obesity in dogs and cats. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2006; 36: 1283–1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Buffington CT. Idiopathic cystitis in domestic cats – beyond the lower urinary tract. J Vet Intern Med 2011; 25: 784–796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Stella JL, Lord LK, Buffington CT. Sickness behaviors in response to unusual external events in healthy cats and cats with feline interstitial cystitis. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2011; 238: 67–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Porters N, De Rooster H, Verschueren K, et al. Development of behavior in adopted shelter kittens after gonadectomy performed at an early age or at a traditional age. J Vet Behav 2014; 9: 196–206. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Amat M, de la Torre JLR, Fatjó J, et al. Potential risk factors associated with feline behaviour problems. Appl Anim Behav Sci 2009; 121: 134–139. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Salman MD, New JJG, Scarlett JM, et al. Human and animal factors related to relinquishment of dogs and cats in 12 selected animal shelters in the United States. J Appl Anim Welfare Sci 1998; 1: 207–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Salman MD, Hutchison J, Ruch-Gallie R, et al. Behavioral reasons for relinquishment of dogs and cats to 12 shelters. J Appl Anim Welfare Sci 2000; 3: 93–106. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Buffington CT, Westropp JL, Chew DJ, et al. Clinical evaluation of multimodal environmental modification (MEMO) in the management of cats with idiopathic cystitis. J Feline Med Surg 2006; 8: 261–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Young RJ. Environmental enrichment for captive animals. Hoboken, NJ: Blackwell Publishing, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mellen JD, Shepherdson DJ. Environmental enrichment for felids: an integrated approach. Int Zoo Yearbook 1997; 35: 191–197. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bashaw MJ, Bloomsmith MA, Marr M, et al. To hunt or not to hunt? A feeding enrichment experiment with captive large felids. Zoo Biol 2003; 22: 189–198. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Markowitz H, LaForse S. Artificial prey as behavioral enrichment devices for felines. Appl Anim Behav Sci 1987; 18: 31–43. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Young RJ. The importance of food presentation for animal welfare and conservation. Proc Nutr Soc 1997; 56: 1095–1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Williams B, Waran N, Carruthers J, et al. The effect of a moving bait on the behaviour of captive cheetahs (Acinonyx jubatus). Anim Welfare 1996; 5: 271–281. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ellis SL. Environmental enrichment: practical strategies for improving feline welfare. J Feline Med Surg 2009; 11: 901–912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ellis SL, Rodan I, Carney HC, et al. AAFP and ISFM feline environmental needs guidelines. J Feline Med Surg 2013; 15: 219–230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Schipper LL, Vinke CM, Schilder MBH, et al. The effect of feeding enrichment toys on the behaviour of kennelled dogs (Canis familiaris). Appl Anim Behav Sci 2008; 114: 182–195. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Clarke D, Wrigglesworth D, Holmes K, et al. Using environmental and feeding enrichment to facilitate feline weight loss. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr 2005; 89: 427. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dantas-Divers LM, Crowell-Davis SL, Alford K, et al. Agonistic behavior and environmental enrichment of cats communally housed in a shelter. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2011; 239: 796–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Meehan CL, Mench JA. The challenge of challenge: can problem solving opportunities enhance animal welfare? Appl Anim Behav Sci 2007; 102: 246–261. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Koffer K, Coulson G. Feline indolence: cats prefer free to response-produced food. Psychon Sci 1971; 24: 41–42. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Osborne SR. The free food (contrafreeloading) phenomenon: a review and analysis. Anim Learn Behav 1977; 5: 221–235. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Fundamentally Feline. Implementing foraging as a feeding protocol. http://www.fundamentallyfeline.com/implementing-foraging-as-a-feeding-protocol (2014, accessed January 31, 2016).

- 32. Wong PT. Frustration, exploration, and learning. Can Psychol Rev 1979; 20: 133–144. [Google Scholar]

- 33. van Kampen HS. Violated expectancies: cause and function of exploration, fear, and aggression. Behav Process 2015; 117: 12–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Herron ME, Buffington CA. Environmental enrichment for indoor cats: implementing enrichment. Compend Contin Educ Vet 2012; 34: E1–E5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Herron ME, Buffington CAT. Environmental enrichment for indoor cats. Compend Contin Educ Pract Vet 2010; 32: E1–E5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Using food puzzles with your cat