Abstract

Series outline:

This is the first article in a two-part series on urinalysis in the cat. The focus of Part 1 is urine macroscopic examination. Part 2, to appear in the May 2016 issue, discusses urine microscopic examination.

Practical relevance:

Urinalysis is an essential procedure in feline medicine but often little attention is paid to optimising the data yielded or minimising factors that can affect the results.

Clinical challenges:

For the best results, appropriately collected urine should be prepared promptly by specialist laboratory personnel for the relevant tests and assessed by a clinical pathologist. This is invariably impractical in clinical settings but careful attention can minimise artefacts and allow maximum useful information to be obtained from this seemingly simple process.

Audience:

Clinical pathologists would be familiar with the information provided in this article, but it is rarely available to general or specialist practitioners, and both can potentially benefit.

Equipment:

Most of the required equipment is routinely available to veterinarians. However, instructions have been provided to give practical alternatives for specialist procedures in some instances.

Evidence base:

Evidence for much of the data on urinalysis in cats is lacking. Validation of the human equipment used routinely, such as dipsticks, is also lacking. As such, the evidence base for feline urinalysis is quite poor and information has largely been extrapolated from the human literature. Information from feline studies has been included where available. In addition, practical clinicopathological and clinical observations are provided.

Introduction

Examination of urine (urinalysis) is often carried out to investigate ill health in cats. It is one of the oldest and most commonly performed laboratory tests in veterinary practice. A complete urinalysis, conducted competently and in a timely fashion, can provide important information about both urinary tract and non-urinary tract disorders at relatively low cost. It is therefore imperative that meticulous attention is paid to this seemingly simple test so that accurate information is obtained and artefacts minimised.

Urinalysis has two components: a macroscopic examination and a microscopic examination. The macroscopic examination includes assessing the urine’s gross appearance, as well as performing a dipstick analysis and urine specific gravity (USG) measurement. It is relatively inexpensive and can be performed quickly and easily. Microscopic examination of urine (to be discussed in Part 2), which includes urine sediment examination and urine cytological assessment, is more demanding and time consuming. It involves greater skill and more equipment to perform competently.

Specimen collection considerations

Timing of collection

Though rarely considered, appropriate timing of collection can be important – and is not necessarily difficult.

Early morning collection of urine (preferably the first urine catch of the day) is best for evaluating tubular function, as urine that has been stored in the bladder overnight is more likely to be concentrated and have an acidic pH, which will retard the dissolution of renal tubular casts.

Freshly formed urine (collected late morning to early evening) is best for microbial culture and assessment of cellular morphology. Fastidious bacteria may only be recoverable from recently formed urine samples and the morphology of cellular constituents may be distorted by prolonged overnight exposure to urine. Immediate centrifugation of recently formed urine and the preparation of an air-dried smear for future reference is prudent if urinary tract infection (UTI) or neoplasia is suspected.1,2

Methods of collection

The three methods of urine collection are cystocentesis, catheterisation and voided sample collection. Patient compliance, risk of trauma to the bladder and level of technical expertise are factors that can influence the choice of collection method. Inducing urine formation in cats by administration of diuretics or parenteral fluids is acceptable if urine is required for microbial culture but is not suitable for routine urinalysis.

Cystocentesis

Cystocentesis allows collection of an uncontaminated urine sample ideal for bacterial or fungal culture. It also allows appropriate timing of collection when timing is important. Cystocentesis is usually performed relatively easily in cats unless they have idiopathic feline lower urinary tract disease (iFLUTD). These cats typically have a small bladder and any handling results in voiding; ultrasound-guided sampling may be more rewarding in these situations.

Microscopic haematuria is frequently present in cystocentesis samples, especially if there is pre-existing bladder inflammation. 2 Cystocentesis is thus not ideal when performing routine monitoring for haematuria in cats with recurrent iFLUTD.

Catheterisation

Catheterisation in cats requires chemical restraint, thus is not routinely used for urine collection unless it has been performed for another reason (eg, treating urethral obstructions).

Voided sample

Collection of a voided sample is simple, and useful when assessing and serially monitoring various chemicals in the urine (eg, glucose, ketones). If the sample is naturally voided (without use of manual expression), haematuria can also be monitored. Voided urine samples can additionally be used for urine protein:creatinine ratio (UPCR) and urine cortisol:creatinine ratio (UCCR) measurement.

Voided samples are sometimes quite easy to obtain as ‘free catch’ samples from cats urinating in litter trays, especially if cats are habituated to collection (eg, for diabetic management). Kit4Cat (Coastline Global) hydrophobic sand or aquarium gravel 3 can also be used to enable urine collection from litter trays. Manual expression of the bladder using digital pressure in an attempt to solicit a urine sample may result in haematuria. It also carries a risk of iatrogenic bladder rupture, particularly if the bladder is friable due to pre-existing pathology, or pressure is excessive. Collection of urine samples from the surface of a clean smooth table top may be adequate for a screening urinalysis if there are no disinfectant residues on the table. 2 Voided urine from kittens can be obtained by stimulating the anogenital reflex with a warm moist cloth or cotton wool ball. This technique may be more successful if the neonate has been separated from the queen for at least an hour. 1

Voided samples are not recommended for urine culture unless they are the only option available or cytological examination of an air-dried smear from voided urine suggests that a fulminant UTI is present (ie, numerous neutrophils, some of which may appear degenerate, accompanying a monomorphous bacterial population). Ideally, any voided sample for urine culture should be collected as a ‘midstream’ urine sample. Excluding the first portion of the urine stream, which is often contaminated during contact with the genital tract, skin and hair, is recommended unless disease of the urethra or genital tract is suspected. 2 Midstream catch is feasible with expressed urine and some voided samples.

If timing of collection of voided samples is important (eg, stored urine is required) there are various practical strategies that can be employed. A litter tray can be removed at night and only provided in the morning for either free catch or litter collection. Aquarium gravel with particles less than 4 mm has been validated for UCCR determination, 3 and presumably would be reasonable for routine chemical analysis, though substantiated evidence for this is lacking.

Urine sample handling and storage

Urine is an unpredictably unstable mixture. In vitro changes can occur rapidly after collection and it is, therefore, recommended that urine samples are examined as soon as possible following collection to eliminate unknown and unpredictable variables. 2 The authors recommend that urinalysis is performed within 60 mins of collection.

Urine containers

Irrespective of the method of collection, once collected, urine should be placed in a leakproof, clear (for visualisation of the physical characteristics of the sample without opening the vessel) and sterile container. Commercially available 70 ml plastic containers (Figure 1) are ideal, as they are flat-bottomed (to prevent inadvertent spillage) and allow all the relevant patient’s details to be clearly recorded on the label.

Figure 1.

An appropriate collection container for cat urine

Subsequent testing will dictate whether the urine sample will require further aliquoting into different tubes (eg, conical tubes for centrifugation, Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Examples of an appropriate tube for aliquoting cat urine for centrifugation

Urine preservation techniques if urinalysis is delayed

Ideally, a complete urinalysis should be performed at the time of urine collection. In a busy veterinary practice, however, this may not always be possible, as the necessary time and appropriate personnel may be unavailable. In vitro changes, including bacterial proliferation, may occur in unpreserved urine stored at room temperature (Table 1). Consequently, if urinalysis cannot be performed on a freshly collected urine sample within a relatively short period of time, the sample will need to be stored and preserved appropriately for later examination.

Table 1.

Artefacts associated with delays in processing unpreserved urine

| Causes of urine artefacts | Effects of urine artefacts | Corrective action | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Delays in processing of urine samples stored at room temperature | • Bacterial proliferation (see below) • Cell degeneration • Cast dissolution • Decreased yield of RBCs, WBCs and casts |

Refrigerate or transport on cold pack | |

| • Formation or loss of crystals | Return the sample to room temperature or warm the sample in a 37°C water bath before microscopic examination. Also verify the presence of crystals via analysis of another urine sample immediately after collection | ||

| • Evaporative loss of volatile substances (eg, ketones) | Use an airtight seal | ||

| Bacterial proliferation/overgrowth | • Increased urine turbidity • False-negative urine glucose • Falsely increased urine pH if urease-producing bacteria present • Falsely decreased urine pH if bacteria use glucose to form acidic metabolites • Alkaline urine can alter cellular components, degrading casts and lysing RBCs in urine • RBC lysis, resulting in false haemoglobinuria rather than haematuria • Decreased concentration of chemicals metabolised by bacteria (eg, glucose, ketones) • Increased number of bacteria in urine sediment • Altered urine culture results |

Refrigerate or transport on cold pack |

WBCs = white blood cells, RBCs = red blood cells

Refrigeration

If sample processing delays of greater than 15–30 mins are anticipated, the urine sample should be refrigerated immediately at 2–8°C to retard bacterial growth and cellular degeneration. If urine has been collected solely for urine culture, then it should be refrigerated immediately. It is imperative that a refrigerated urine sample is returned to room temperature before routine dipstick analysis. This may also help to redissolve any substances that may have precipitated at cold temperatures.2,4

Refrigeration should be avoided if the sediment is to be evaluated specifically for struvite or calcium oxalate crystalluria.4,5 Refrigeration can cause a pronounced increase in the number of these crystals, which is not always reversed by returning the sample to room temperature or warming the sample in a 37°C water bath prior to microscopic examination.

Chemical preservation

Several chemical substances have been purported to help prevent in vitro degenerative changes in the constituents of urine (cells and casts). In the authors’ experience, the use of chemical preservatives (other than EDTA anticoagulant) generally introduces artefacts. If samples are to be sent to a laboratory for further processing, it is worthwhile checking with the referral laboratory for its preferred urine preservatives.

Formalin Urine cells, casts and crystals can be preserved by adding four or five drops of neutral buffered formalin per 10 ml of urine, but this is only applicable for urine submitted for unstained wet-prep examination. Urine subjected to formalin treatment should not be used to prepare air-dried direct smears or cytospin smears destined for Romanowsky staining (eg, Diff-Quik), as the formalin will adversely affect Romanowsky staining techniques. For this reason, urine samples treated with formalin should be clearly labelled when being sent to an external veterinary laboratory to avoid confusion and generation of spurious results. Such samples should be accompanied by a duplicate ‘untreated’ urine sample, aliquoted into a separate container, which can be used for microbial culture, dipstick analysis and air-dried cytological smear assessment.

EDTA anticoagulant Aliquoting urine into tubes containing EDTA anticoagulant helps to preserve cellular detail, particularly where air-dried urine cytological smear assessment is required. It should always be ensured that EDTA tubes are used within their expiry date and are filled with urine to the designated level. These samples are unsuitable for urine culture.

Other chemical preservatives Other, less commonly used urine chemical preservatives include thymol, toluene and boric acid. Their use, however, is associated with artefacts, which vary depending on the preservative. 6 For example, urine samples sent away for laboratory culture using boric acid as the preservative were found to be significantly less likely to give a positive culture result when compared with urine submitted in a plain sterile tube. 7

Freezing

Freezing can preserve urine for dipstick analysis but is unsuitable for wet-prep sediment examination, air-dried stained urine cytology examinations or microbial culture. 2

Artefacts associated with urine preservation

Refrigeration and chemical preservation can result in artefacts in urine samples presented for urinalysis. Some of these artefacts (Table 2) are reversible.1,2 Bacterial contamination, however, creates similar artefacts to those associated with unpreserved urine samples (Table 1).

Table 2.

Artefacts associated with preserved urine samples

| Urine preservation technique | Types of urine artefacts | Corrective action |

|---|---|---|

| Refrigeration | • Possible inhibition of enzyme reactions (eg, glucose) on urine dipstick analysis • Higher urine specific gravity in cold samples • Tendency for in vitro formation of struvite and calcium oxalate crystals |

Bring urine sample to room temperature before examination |

| • In vitro precipitation of amorphous urates or phosphates | Verify via analysis of another urine sample immediately after collection | |

| Formalin and other chemical preservatives | • Unreliable dipstick analysis and microbial culture • Poor stain uptake when air-dried smears are stained for cytological assessment |

Provide another aliquot of untreated urine collected at the same time and refrigerated |

Performing and interpreting the macroscopic urinalysis

A complete urinalysis includes a macroscopic and microscopic examination of the urine specimen.

Macroscopic examination is relatively quick, cheap and easy. It entails a subjective assessment of the physical properties of urine (colour, turbidity, odour and volume) and a USG reading, which is objectively measured with a refractometer. It also includes semiquantitative assessment of the chemical properties of urine by dipstick analysis.

Physical properties

Colour

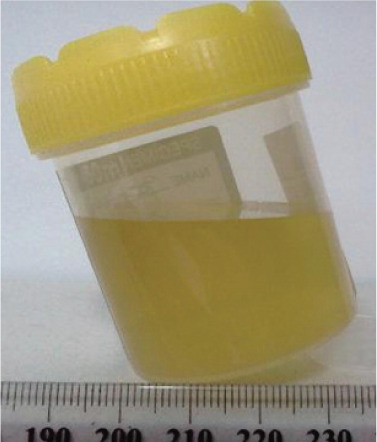

Urine samples should be examined for colour through a clear container held against a white background under good lighting conditions. Normal cat urine may be light yellow or yellow to amber in colour (Figure 2). This normal coloration is mainly attributable to the presence of urochrome and urobilin pigments, which are both by-products of normal metabolic processes. Urochrome is a yellow, lipid-soluble, sulphur-containing pigment that results from oxidation of the colourless metabolite urochromogen. Increased urochrome excretion can occur in fever and starvation, and should be assessed in the light of the clinical history and USG.

Discoloration of urine is one of the reasons that cat owners seek veterinary attention. The most common causes for discoloured urine in cats are haematuria, haemoglobinuria, myoglobinuria and bilirubinuria (Figure 3, Table 3). Various drugs and foods have also been documented to cause urine discoloration in humans. In cats, urine discoloration can occur after treatment with the antibiotics clofazimine (pink to brown) and rifampicin (orange–red).1,2,8,9

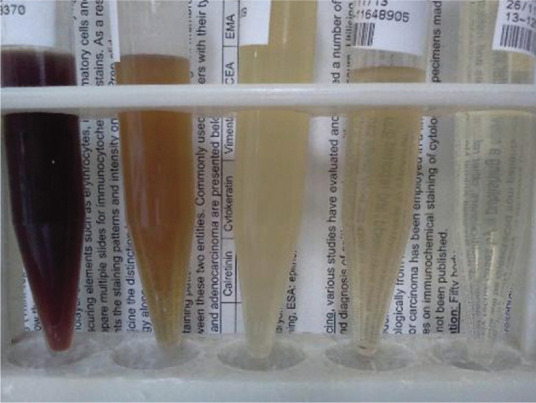

Figure 3.

Cat urine samples displaying a range of colours and turbidity, with obvious discoloration noted in the two samples on the far left. Increased turbidity, evident because background print is obscured, is present in the three samples on the left

Table 3.

Causes of abnormal-coloured urine in cats

| Colour | Cause |

|---|---|

| Colourless or pale yellow | Dilute urine |

| Dark yellow or yellow–orange | Concentrated urine, bilirubin, excess urobilin |

| Yellow–green to yellow–brown | Bilirubin/biliverdin |

| Brown to black | Methaemoglobin, myoglobin, bile pigments |

| Red, pink, red–brown, red–orange to orange | Haematuria, haemoglobinuria, myoglobinuria, methaemoglobinuria, porphyrins, clofazimine or rifampicin treatment |

| Blue | Methylene blue |

| Blue–green | Methylene blue, Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection, biliverdin (old urine sample) |

| Milky white | Pyuria, lipiduria, phosphate crystals, sperm |

Turbidity

Turbidity can be assessed semiquantitatively by how clearly one can visualise background newsprint through a well-mixed urine sample in a clear container under good lighting (Figure 3). Freshly collected urine from normal cats is usually clear (Figure 1). However, clear urine must still be analysed to ensure no abnormalities are present.

Turbidity due to lipiduria in healthy cats is often localised to the surface layers, as lipids rise to the top of urine samples. Artefactual turbidity may arise as a result of changes in temperature and pH. Following refrigeration, for example, urine can become cloudy due to precipitation of crystals; this can sometimes be reversed by returning the sample to room temperature or warming the sample in a 37°C water bath. Other causes of artefactual turbidity in urine samples include contaminants in the collection container, semen and faeces. 2

Abnormal turbidity or cloudy urine may be associated with increased numbers of micro-organisms, cellular elements (red blood cells [RBCs], white blood cells [WBCs], epithelial cells) or crystalluria. Milky turbid fresh urine specimens are most commonly associated with pyuria. Abnormally turbid urine should always be subjected to microscopic examination to further investigate the underlying cause.

Macroscopic haematuria typically results in brownish to red turbid urine. Haemoglobinuria and myoglobinuria result in brownish to red (occasionally black) transparent urine.1,2,9

Odour

Although odour may vary in intensity depending on the gender of the cat (eg, the urine of mature intact male cats has a strong characteristic odour), in the authors’ experience urine odour is not pathognomonic for any particular disease process.

Volume

Normal adult cats produce a urine volume of 18–28 ml/kg/day (5–60 ml/kg/day in kittens). Polyuria is defined as a urine volume exceeding 40 ml/kg/day.1,2

USG

USG is the only test of renal function (ie, the kidneys’ ability to modify the solute content of the urine via dilution and concentration) performed during routine urinalysis.

USG reflects the total solute concentration in the urine. Osmolality is more accurate than USG as it depends solely on the number of particles in the solution (not a combination of number, particle size and molecular weight as in USG). However, osmolality is not readily measured in practice, while USG is easy and can be performed in-house using a refractometer (see box on page 195).

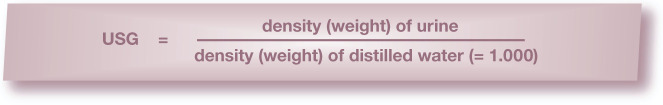

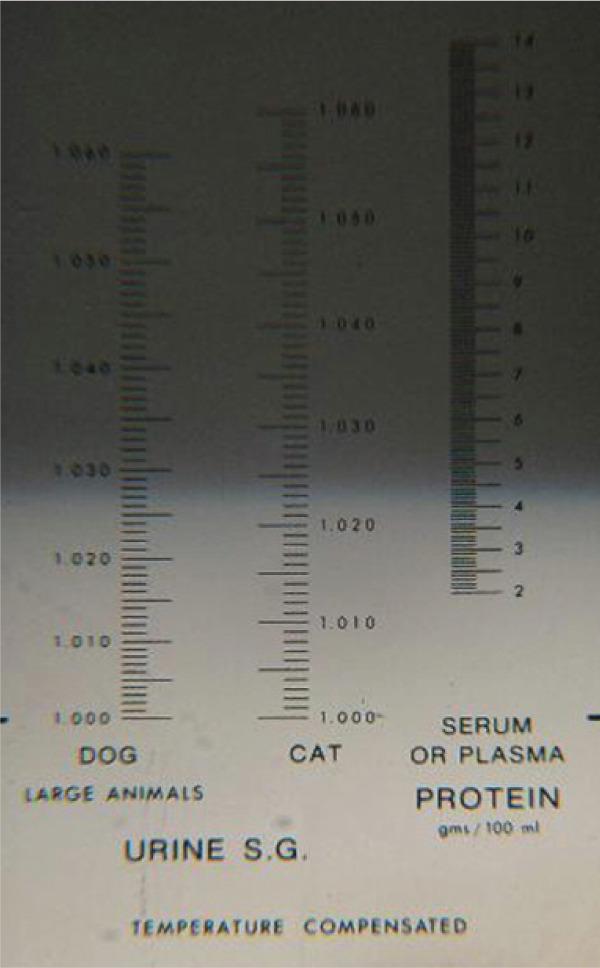

Figure 4.

(a) A temperature-compensated optical veterinary refractometer and (b) the reticle viewed through the eye-piece when the refractometer is held up to the light

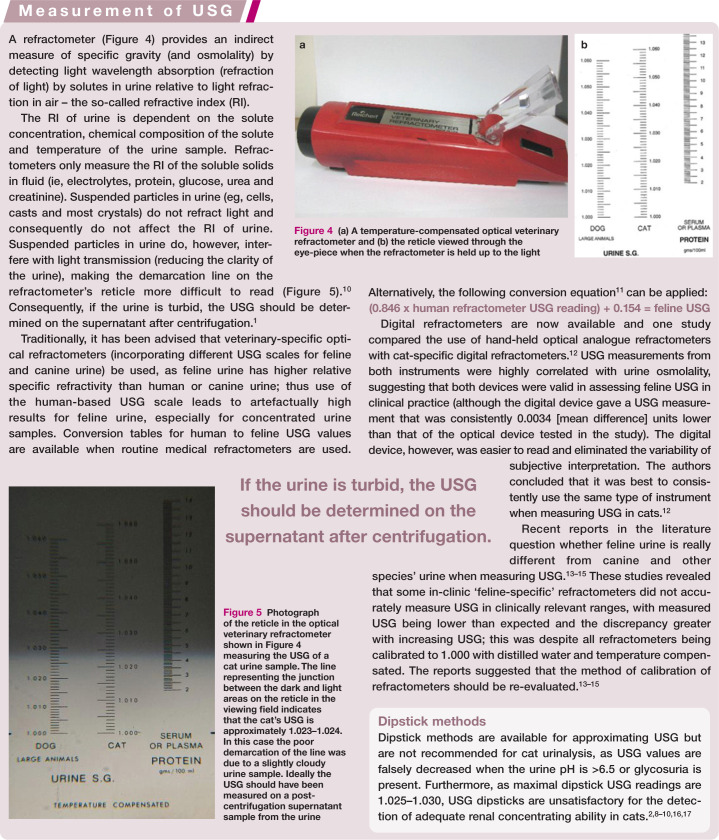

Figure 5.

Photograph of the reticle in the optical veterinary refractometer shown in Figure 4 measuring the USG of a cat urine sample. The line representing the junction between the dark and light areas on the reticle in the viewing field indicates that the cat’s USG is approximately 1.023–1.024. In this case the poor demarcation of the line was due to a slightly cloudy urine sample. Ideally the USG should have been measured on a postcentrifugation supernatant sample from the urine

Care must be taken to obtain accurate, repeatable and reliable USG readings from a digital or analogue refractometer. USG measurements should be made prior to the commencement of any treatment that has the potential to alter USG (Table 4).

Table 4.

Checklist to help ensure accurate results when using a refractometer to measure urine specific gravity (USG)

| Check points | Action/considerations |

|---|---|

| Type of refractometer used | Use a refractometer with a cat-specific scale (Figures 4 and 5) incorporated into the viewing screen (reticle) or use conversion factor (see page 195) |

| Ensure regular refractometer calibration | Ideally, refractomer calibration should be checked daily with distilled water (USG 1.000) or a 5% NaCl solution in distilled water (USG 1.022). Do not use commercially prepared protein standards for instrument calibration as they contain non-protein preservatives that increase refractive index values 11 |

| Use temperature-compensated refractometers | Temperature affects the density of urine and hence the USG. For non-temperature compensated refractometers, read at or near 20°C for accurate measurement 10 |

| Avoid USG measurements on turbid urine | USG should be determined on the supernatant after centrifugation of turbid urine 1 |

| Reading USG results >1.035 off refractometer scales that only read up to 1.035 | Dilute urine 1:1 with distilled water and then double the last two digits of the reading obtained to give the true USG1,10 |

| Factors increasing USG1,2,10 | Consider: • Glucosuria – a concentration of 1 g/dl (55.5 mmol/l) of glucose in urine will increase the USG by 0.004–0.005 units • Proteinuria – a concentration of 1 g/dl (10 g/l) of protein in urine will increase the USG by 0.003–0.005 units • Turbidity of urine • Cold temperatures • Free haemoglobin • Increased lipid content • Radiographic contrast media |

| Factors decreasing USG | Measure USG prior to fluid therapy and diuretics |

| Take appropriate care of the refractometer 11 | Rinse and dry the clear optical measuring surface and the underside of the cover plate that comes into contact with the measuring surface. Avoid scratching the clear optical measuring surface |

Interpretation

USG in healthy adult cats may range from 1.001–1.085, although a recent large-scale study in 1040 apparently healthy adult cats reported that 88% of the cats concentrated their urine to a USG of >1.035 on a random single urinalysis. 16 The same study also revealed that dietary modification had only a modest effect on USG, with increasing dietary moisture content more likely to lower USG in female cats. 16

USG must always be assessed and interpreted in conjunction with patient health, hydration status and azotaemia.1,2

Hyposthenuria (USG <1.008) implies that the kidneys are capable of diluting the glomerular filtrate. While persistent hyposthenuria usually suggests that renal dysfunction is not present, some cats with renal dysfunction are still capable of producing hyposthenuric urine. 1 UTIs can also result in hyposthenuria.

Isosthenuria (USG 1.008–1.012) indicates that the glomerular filtrate has not been altered by the kidneys.1,2 Isosthenuria occurs occasionally in healthy cats but, when accompanied by dehydration and azotaemia, is indicative of decreased renal function. Persistent isosthenuria in a non-azotaemic cat is suggestive of a concentrating defect.

Hypersthenuria (USG >1.012) demonstrates that the kidneys are capable of concentrating the glomerular filtrate to some extent. Cats should be able to concentrate to at least 1.040 in the face of dehydration or azotaemia. Some cats with less than 25% functional renal mass have been able to concentrate to >1.040, suggesting that 1.040 may be a conservative cut-off for differentiating pre-renal from renal azotaemia. It has been proposed that, in azotaemic cats, >1.045 implies adequate concentration, 1.040–1.045 is questionable and <1.040 inappropriate.1,17 The production of very concentrated urine (>1.050) in a dehydrated or azotaemic cat suggests reduced renal perfusion (hypovolaemia, hypotension or cardiac disease) rather than renal disease. 17

Difficulties in interpreting feline USG may be encountered with cats in renal failure that retain concentrating ability for a variable period after the onset of azotaemia. Cats with 58–83% reduction in renal mass can still produce hypersthenuric urine, with a USG of 1.022–1.067. Consequently, some of these cats could be misclassified according to the USG as having pre-renal azotaemia.1,17,18 Assessment of USG in neonates is also challenging. In comparison with adults, neonates tend to have poorer renal concentrating ability. The USG in random samples from healthy neonatal kittens is typically low (1.006–1007). USG readings of up to 1.038 have been observed in kittens by 4 weeks of age and up to 1.080 may be possible by 8 weeks of age.1,19

Routine evaluation of USG is required for interpretation of some of the test results from a complete urinalysis. The amount of any substance in the urine, such as protein, must be interpreted in the light of the USG. For example, a 2+ dipstick protein result on a urine sample with a USG of 1.060 indicates mild proteinuria, in contrast to a 2+ dipstick protein result on a urine sample with a USG of 1.007, which indicates a significant proteinuria. 2

Chemical properties

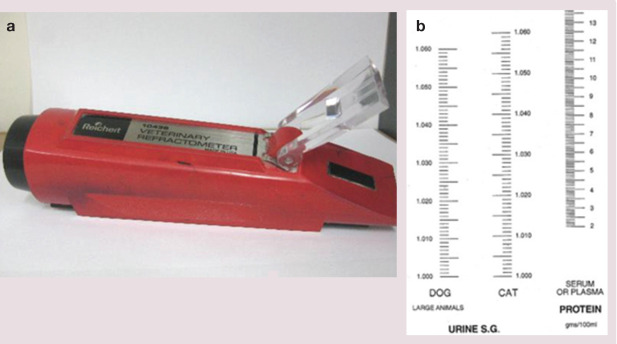

Many chemical properties of cat urine (including pH, protein, glucose, ketones, haemoglobin/occult blood and bilirubin) can be easily and rapidly assessed in-house with the use of dry reagent test strips (dipsticks) (Figure 6). Dipstick analysis provides a semi-quantitative measurement of these various chemical parameters, some of which need to be interpreted in light of the refractometer USG reading. Note that not all chemical parameters present on commercially available dipsticks yield valid results when tested on cat urine.1,2,6,8 –10 Urobilinogen, USG, nitrite and leukocyte esterase activity (‘leukocytes’) test pads should be considered unreliable in cats.

Figure 6.

(a,b) Examples of commercially available urine dipsticks that may be used to perform urinalysis in cats. Note that of the multiple test pads available on these dipsticks, only six (protein, pH, blood, ketones, bilirubin and glucose) provide meaningful and reliable information in cats. The other test pads (urobilinogen, leukocytes, nitrite and USG) are either unnecessary or provide unreliable results in cats. It should always be ensured that dipsticks have not reached their expiry date and are stored and read according to the manufacturer’s instructions

Dipstick analysis should be performed before centrifugation on either a fresh urine sample or a refrigerated urine sample that has been warmed to room temperature. Urine contact can be achieved by immersion or pipetting. If performing the former, immersion of the dipstick in urine should be complete but brief, to prevent reagents leaching out of pads; excess urine should be removed by tapping the strip against the container to prevent run-off of reagents. The strip should then be held horizontally when comparing it against the chart. 1 The authors, however, advocate the use of a pipette to carefully place a drop of urine on each pad of the dipstick, which is laid horizontally. This avoids any run-off of reagents (the pipette can also be used to load the refractometer during USG estimation).

Further ‘tips and traps’ regarding the use of dipsticks are outlined in Table 5.

Table 5.

Urine dipstick testing in cats – dos and don’ts

| Dipstick analysis – dos | Dipstick analysis – don’ts | |

|---|---|---|

| • Dipstick analysis should be performed before centrifugation; if there is marked haematuria, RBCs can be sedimented and the dipstick analysis performed on the supernatant | • Don’t touch dipstick pads with your fingers • Don’t store the dipsticks in the refrigerator; they should be stored in a cool, dry place |

|

| • Check the reaction times for each pad and adhere to them • The only test pads required for testing feline urine are pH, protein, glucose, ketones, haemoglobin/blood and bilirubin |

• The urobilinogen pad is unnecessary as many normal animals have none detectable (frequently catabolised to urobilin by photo-oxidation in aged specimens or during retention of urine) | |

| • Test pads on the dipstick should be read manually by comparing against the test chart provided under good lighting. An automated dipstick reader, if available, is more accurate | • Don’t use the nitrite pad. This is intended to screen for bacteriuria, as nitrite is produced by some bacteria; however, feline urine normally contains ascorbic acid, so these pads often yield false-negative results. A positive result would warrant further urine sediment examination or urine culture | |

| • Keep the lid of the dipstick container tightly closed to avoid oxidative damage from prolonged exposure to air or light, which can affect glucose and blood test pads | • Don’t use the leukocyte pad. Most normal feline urine specimens yield false-positive results even if they do not contain leukocytes, suggesting either the presence of other non-leukocyte-specific esterases or higher esterase activity in feline urine | |

| • Keep the lid of the urine container tightly closed to prevent evaporative loss of ketones | • Don’t use expired test strips. False-negative reactions are common in the glucose test pad of out-of-date dipsticks |

Information based on studies 1, 2, 8, 9, 20 and 21. RBCs = red blood cells

pH

Normal urine pH in cats is 5.0–7.5. 22 Urine pH reflects renal regulation of H+ and HCO3− and is affected by many renal and extrarenal factors.1,10

Acidic urine may result from the ingestion of a meat diet, acidifying agents/diets, metabolic or respiratory acidosis, paradoxical aciduria in metabolic alkalosis and protein catabolic states.1,2,22 Alkaline urine may result from UTIs associated with urease-producing bacteria such as Staphylococcus aureus, Proteus species and Klebsiella species, diets low in protein or rich in vegetables, ‘post-prandial alkaline tide’ (occurs while acid is being secreted into gastric juice), alkalinising agents, metabolic alkalosis, respiratory alkalosis (eg, hyperventilation due to stress of travel or veterinary visit), distal renal tubular acidosis and urinary retention (eg, urinary tract obstruction).1,2,22 Table 6 outlines some causes of falsely increased or decreased pH readings in cat urine.

Table 6.

Artefacts associated with dipstick analysis of urine pH

| Factors that can increase urine pH | Factors that can decrease urine pH |

|---|---|

| • Alkalinising fluids and drugs including acetazolamide, sodium bicarbonate, chlorothiazide and potassium citrate | • Acidifying drugs: ammonium chloride, ascorbic acid at high doses, citric acid and methionine |

| • Containers standing open for prolonged periods prior to testing, resulting in loss of carbon dioxide | • Contamination of the pH pad by buffer leaching from the adjacent protein test pad |

| • Containers standing open for prolonged periods prior to testing, resulting in loss of carbon dioxide | • Ingestion of meat

• High protein diets |

| • Low protein diets | |

| • A very recent meal: ‘post-prandial alkaline tide’ likely due to increased acid secretion into stomach |

Information based on studies 1, 2 and 8

A pH meter may be required to accurately determine the pH (especially in highly coloured urine). In one study, dipstick results were consistently lower than those obtained using a pH meter in cats. 23

Protein

Urine dipsticks are usually the first-line screening test for detecting the presence of proteinuria. Their colorimetric test methodology primarily measures albumin. The sensitivity and specificity of dipsticks for measuring albuminuria in cats are 90% and 11%, respectively; false-positive results are seen more frequently in cats than in dogs. 24

On the Combur-10 Test dipstick (Cobas) (Figure 6), the protein reaction is graded as negative, 1+, 2+ or 3+, corresponding to <0.06, 0.3, 1.0 and 5 g/l, respectively. The product insert states that the strip’s practical detection limit is 0.06 g/l of albumin. Other commercially available urinalysis dipstick test strips may be graded differently. The product’s package insert information should be checked for the latest updates.

The urinalysis dipstick test may be affected by turbidity and the use of centrifuged supernatant is preferred for turbid samples.1,2 Factors that may erroneously affect the protein reading on the urine dipstick are outlined in Table 7.

Table 7.

Artefacts associated with dipstick analysis of urine protein

| False negatives – causes | False positives – causes |

|---|---|

| • Bence Jones proteinuria

• Dilute urine |

• Highly alkaline dilute urine (pH >9) or moderately alkaline concentrated urine |

| • Acidic urine | • Quaternary ammonium disinfectants or chlorhexidine |

Information based on studies 1, 2 and 24

Increased dipstick protein in highly alkaline urine can be confirmed by another semiquantitative assay, the sulphosalicylic acid (SSA) precipitation test. This test is less sensitive to albumin but will detect other proteins such as globulins and Bence Jones proteins. False decreases by this method occur with highly buffered alkaline urine or dilute urine. False increases occur with massive doses of cephalosporins, sulpha drugs or penicillin, as well as use of radiographic contrast agents or thymol (a urine preservative).1,2,24

Proteinuria detected by urine dipstick and SSA has historically been interpreted in conjunction with the USG and urine sediment.1,2 For example, when using urine dipsticks, a negative to trace protein reaction is expected in healthy cats at a USG <1.020; while at a USG <1.035, the reaction should at most be 1+. In highly concentrated samples, this reading should not exceed 2+.1,2 Some researchers suggest that this interpretation may not be correct, given the limits of conventional dipstick test sensitivity, and that any true positive result for protein, regardless of urine concentration, may be abnormal. 24 A study evaluating cats with chronic kidney disease found that a positive urine dipstick result (⩾trace) with a positive SSA test (⩾0.05 g/l), a positive SSA test alone, or ⩾2+ urine dipstick result alone, were indicative of proteinuria and warranted protein quantification with a UPCR. 25

A persistent proteinuria is defined as positive test results on three or more occasions, at least 2 weeks apart. 24 If persistent proteinuria is identified in the absence of an active sediment, a UPCR should be performed. A UPCR is also recommended for assessing any chronic kidney disease in cats, as outlined in the International Renal Interest Society (IRIS) guidelines. 24

The UPCR eliminates the necessity of a 24 h urine protein measurement but the test is best performed after a period of confinement without access to a litter tray to maximise the volume of urine on which it is based. In dogs, to avoid the effects of stress it is strongly advised that three separate samples are collected at home and then pooled, with a single measurement made by the laboratory. 26 This collection protocol may also be applicable to cats, especially given that cats often exhibit much greater stress responses than dogs.

Standard practice chemistry analysers cannot be used to measure urine protein; different dedicated reagents are required for such measurements on specialised machines within the referral laboratory. Standard practice chemistry analysers are calibrated for plasma, in which the concentration of protein is 500–1000 times higher than in urine, and so cross contamination is a significant issue. In addition, creatinine concentrations are 25–100 times higher in urine than in plasma, which makes it necessary to dilute urine samples before measurement. 27 In dogs, urine samples for UPCR determination are required to be immediately frozen to increase stability and minimise the risk of IRIS misclassification; it has been shown that UPCR increases significantly after 12 h both at room temperature and at 4°C. 28 It is not known whether this is also the case in cats, but it would seem prudent to submit a frozen sample of feline urine for UPCR measurement if time-to-assay is likely to exceed 12 h. A recent study has also demonstrated that, in dogs, inter-laboratory variability in UPCR ratio measurement may influence the magnitude of the estimated proteinuria. 29

Multistix PRO (Bayer) dipsticks that measure urine protein and creatinine concentrations and UPCR have been evaluated. In cats, the dipstick results for UPCR did not correlate with the quantitative values. 30

Albumin

Normal cats have a urine albumin concentration of <0.01 g/l at a USG of 1.010. 1 Semiquantitative, species-specific, ELISA-based microalbuminuria dipsticks are available to detect 0.01–0.3 g/l of urinary albumin in feline urine (E.R.D.-HealthScreen Feline Urine Test; Heska). As urine concentration influences the concentration of albumin, the tests are performed on urine samples that have been diluted to a USG of 1.010.

In humans, most cases of renal failure occur secondarily to diabetes mellitus or essential hypertension, and evidence suggests that early increases in albuminuria (microalbuminuria) reflect glomerular damage that is undetectable by UPCR determination.1,27,31 However, routine screening of cats is not justifiable, especially for those that are clinically healthy. Healthy cats may show an age-related increase in urinary albumin concentrations. In one study, 73% of cats over 16 years had microalbuminuria. 32

Although it is likely that patients with microalbuminuria have renal lesions, not all cases require investigation (as the lesions may be mild and non-progressive) and, in some cats, micoalbuminuria may be transient. 1 In addition, many systemic disease states, including hyperthyroidism, have been associated with microalbuminuria in non-azotaemic cats. 27 Thus, even if it is a marker for incipient renal disease, many of the other diseases linked with microalbuminuria can lead to illness or death before renal disease is of any clinical consequence. 27 Some studies have also demonstrated that the semiquantitative microalbuminuria test should not be relied on as the sole determinant of proteinuria; while microalbuminuria and proteinuria are commonly seen in cats with a variety of diseases, they are not necessarily both increased and the UPCR can be increased despite negative microalbuminuria. 31

Glucose

Normal urine should be negative for glucose. Based on a scientific conference abstract that detailed a study on six healthy cats, it is usually accepted that glucose is completely reabsorbed by the feline proximal renal convoluted tubules if the serum glucose is less than 15–16 mmol/l (270–288 mg/dl). 33 However, some cats do seem to display glucosuria when serum glucose is less than 15 mmol/l (L Fleeman, 2013, personal communication). Thus conventional wisdom may be incorrect due to small study population size and healthy cats, or it may be that cats are difficult to assess accurately due to transient stress hyperglycaemia prior to urine collection. 34

One study compared urine glucose measurement by the Glucotest Feline Urine Glucose Detection System (Purina; for use in litter) and the Multistix (Bayer) dipstick. The Glucotest was found to more accurately estimate urine glucose than the Multistix dipstick; 35 however, the test has since been withdrawn from the market. The Bayer Multistix was inaccurate in approximately 25% of cases (79% were overestimations, which is a concern for diabetic monitoring and also for diagnosis as there was an overestimation in samples that were negative for urine glucose). Assessment of glucose in this study was by visual test pad inspection, and not by the Clinitek 100 Analyzer (Bayer) used in laboratories; thus the accuracy of the automated analysis is unknown. 35

Glucosuria in cats occurs with hyperglycaemia (due to stress, diabetes mellitus, corticosteroids, progestagens, thiazide diuretics, glucose-containing fluids) or renal pathology including proximal renal tubulopathy (especially due to nephrotoxic insult; eg, aminoglycoside, amphotericin B, lilies), occasionally chronic kidney disease, and transiently after urethral obstruction.1,22,34,36

Factors that may erroneously affect the glucose reading on the urine dipstick are outlined in Table 8.

Table 8.

Artefacts associated with dipstick analysis of urine glucose

| False negatives and underestimations– causes | False positives and overestimations– causes |

|---|---|

| • Refrigerated urine: samples should be returned to room temperature before testing | • Bayer Multistix test pads (other available dipsticks not validated for cats) |

| • Ketones: if urine is positive for ketones and negative for glucose, check blood glucose on a fluoro-oxalate blood sample and measure serum beta-hydroxybutyrate | • Cephalexin and enrofloxacin can both cause false-positive results with urineglucose tablets and strips in dogs.

37

Cats may similarly be affected |

| • Out-of-date pads | |

| • Enrofloxacin has caused underestimation of glucose in dogs in in vitro tests (ie, enrofloxacin added directly to urine samples containing dextrose).

37

Cats may similarly be affected |

Information based on studies 1 and 2

Ketones

Normal cat urine should be negative for ketones as ketones are completely reabsorbed by the renal proximal tubules. 1

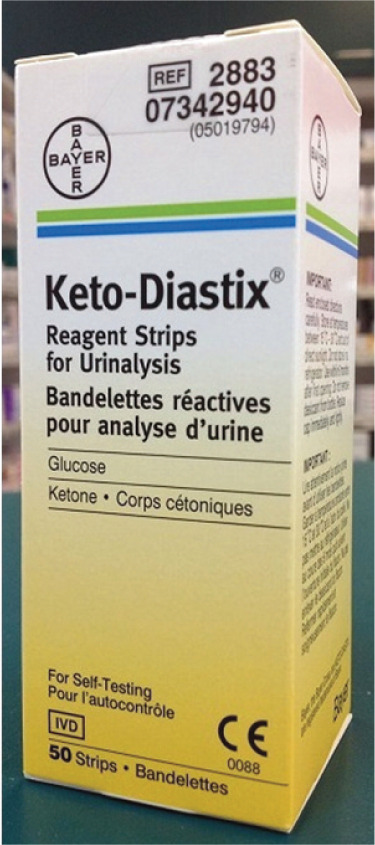

Dipstick pads (eg, Keto-Diastix; Bayer, Figure 7) and tablets use nitroprusside reactions that only detect acetoacetate and acetone, and not beta-hydroxybutyrate (βOHB), the ketone largely responsible for metabolic acidosis and the main ketone in diabetes mellitus. Urine assays tend to underestimate the degree of ketonaemia in initial diabetic assessment. Conversely, there is overestimation after treatment with insulin as serum βOHB metabolises to acetoacetate, and ketonuria should be expected for at least 3–4 days despite successful treatment of diabetic ketoacidosis.1,10,34

Figure 7.

Keto-Diastix urinalysis strips may be used at home by cat owners (in collaboration with their veterinarian) to monitor diabetic cats for any evidence of ketonaemia – which would prompt immediate medical intervention. Simultaneously, the strips can be used to identify consistent negative glucosuria, consistent with hypoglycaemia due to insulin overdose or remission

Causes of ketonuria include diabetic ketosis/ketoacidosis, starvation or prolonged anorexia, lactation, hyperthyroidism and paracetamol toxicity. 1 Factors that may erroneously affect the ketone reading on urine dipsticks are outlined in Table 9.

Table 9.

Artefacts associated with dipstick analysis of urine ketones

| False negatives – causes | False positives – causes |

|---|---|

| • Delayed sampling: acetone is volatile and evaporates, acetoacetic acid is degraded by bacteria | • Highly pigmented urine (haematuria, haemoglobinuria)

• Highly concentrated, acidic urine (trace reactions) |

| • Out-of-date dipsticks (ketone pads are sensitive to the effects of moisture, heat and light) | • Compounds with sulfhydryl groups (eg, cystine) |

| • Presence of βOHB (βOHB is not detected by reagent strips) |

Information based on studies 1, 2 and 9. βOHB = beta-hydroxybutyrate

Bilirubin

Bilirubin in urine is conjugated (only conjugated bilirubin is water soluble and able to be freely filtered by the glomerulus). Unconjugated bilirubin (bound to albumin) can only escape through the glomerulus if there is significant glomerular disease and thus would also be associated with significant proteinuria.1,2,6,8 Cats have a high renal threshold for bilirubin and feline kidneys do not conjugate bilirubin, thus feline bilirubinuria is always abnormal and suggests the presence of a hepatobiliary or haemolytic disorder.

Blood

The dipstick pad for ‘blood’ reacts with haem-containing products. 10 It is more sensitive to haemoglobin (diffuse colour change) than intact erythrocytes (spotting). The pad can be positive due to haematuria, haemoglobinura or myoglobinuria, so a positive test needs to be assessed with concurrent sediment examination, haematology and serum biochemistry. Myoglobinuria can be distinguished from haemoglobinuria by adding 80% saturated ammonium sulphate to urine (requires alkalinisation first so not usually performed in practice or in commercial laboratories). However, it is easier to assess the likelihood of myoglobinuria by checking the serum creatine kinase concentration. 32

In humans, up to 5 RBCs/µl (referred to as physiologic microhaematuria) is normal. Equivalent quantitative determinations have apparently not been carried out for cats, but a few RBCs are often present in the urine of normal cats. 2 With commercially available dipsticks, such as the Combur-10 Test, the practical detectable limit for intact RBCs is 5 RBCs/µl of urine; and for haemoglobin or haemolysed RBCs is 10 RBCs/µl of urine (refer to product insert). In comparison, visual detection of blood in urine is only possible when RBCs number approximately 2500/µl of urine. 2

Interpretation of urine dipstick pads for blood and haemoglobin may be problematic in the presence of severe haematuria as the pads may be unable to reliably differentiate haematuria and haemoglobinuria. Sediment examination of the urine sample may be useful in this instance although RBCs may lyse in vitro, especially in dilute urine, 8 and up to 50% of RBCs may be lost following centrifugation, 10 potentially resulting in an erroneous diagnosis of haemoglobinuria rather than haematuria. Other factors that may erroneously affect the blood pad on the urine dipstick are outlined in Table 10.

Table 10.

Artefacts associated with dipstick analysis of urine ‘blood’

| False negatives – causes | False positives – causes |

|---|---|

| • Failure to resuspend blood cells that have settled to the bottom of the tube | • Iodine and bromide (unlikely as requires large quantities of contaminants) |

| • Nitrites produced in UTIs (unlikely)

• Ascorbic acid (in large quantities) • Formalin as a preservative • Out-of-date reagents |

• Hypochlorite and other oxidizing agents in disinfectants (also unlikely) |

UTIs = urinary tract infections

Key Points

Urinalysis can be performed in-house or urine samples can be sent to a veterinary laboratory for examination.

To competently perform a complete and thorough urinalysis in-house – and avoid erroneous results and interpretations – it is important to be aware of the pitfalls and limitations associated with the technique.

Precautions should be taken when submitting urine samples to a veterinary laboratory, as improper handling and delays in transit can affect the integrity of some urine constituents, leading to spurious results.

Footnotes

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Charles JA. Practical urinalysis. Proceedings: CSI: clinical solutions and innovations. The University of Sydney Post Graduate Foundation in Veterinary Science, Brisbane, 2006, pp 15–75. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Osborne CA, Stevens JB. Urinalysis: a clinical guide to compassionate patient care. Shawnee Mission, KS, USA: Bayer Corporation, 1999, pp 41–131. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Goossens MMC, Meyer HP, Voorhout G, et al. Urinary excretion of glucocorticoids in the diagnosis of hyperadrenocorticism in cats. Dom Anim Endocrinol 1995; 12: 355–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Albasan H, Lulich J, Osborne CA, et al. Effects of storage time and temperature on pH, specific gravity, and crystal formation in urine samples from dogs and cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2003; 222: 176–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sturgess CP, Hesford A, Owen H, et al. An investigation into the effects of storage on the diagnosis of crystalluria in cats. J Feline Med Surg 2001; 3: 81–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chew DJ, DiBartola SP. Sample handling, preparation, analysis and urinalysis interpretation. In: Interpretation of canine and feline urinalysis. Nestle Purina Company, clinical handbook series, 1998, pp 9–21. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rowlands M, Blackwood L, Mas A, et al. The effect of boric acid on bacterial culture of canine and feline urine. J Small Anim Pract 2011; 52: 510–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Archer J. Urine analysis. In: Villiers E, Blackwood L. (eds). BSAVA manual of canine and feline clinical pathology. 2nd ed. Quedgeley, BSAVA, 2005, pp 149–168. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sink C, Weinstein N. Routine urinalysis: physical properties and chemical analysis. In: Practical veterinary urinalysis. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, 2012, pp 19–53. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Stockham SL, Scott MA. Urinary system. In: Fundamentals of veterinary clinical pathology. 2nd ed. Ames, Iowa: Blackwell Publishing, 2008, pp 416–449. [Google Scholar]

- 11. George JW. The usefulness and limitations of hand-held refractometers in veterinary laboratory medicine: an historical and technical review. Vet Clin Path 2001; 30: 201–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bennett AD, McKnight GE, Dodkin SJ, et al. Comparison of digital and optical hand-held refractometers for the measurement of feline urine specific gravity. J Feline Med Surg 2011; 13: 152–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tvedten HW, Norén A. Comparison of a Schmidt and Haensch refractometer and an Atago PAL-USG Cat refractometer for determination of urine specific gravity in dogs and cats. Vet Clin Path 2014; 43: 63–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tvedten HW. Urinalysis: update on specific gravity measurement, chemical analysis of urinary protein, creatinine, urea and electrolytes. Proceedings contribution, American College of Veterinary Pathologists Annual Meeting, Atlanta, Georgia, USA, 2014. www.acvp.org/meeting/2014/appFiles/87_Tvedten.docx. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tvedten HW, Ouchterlony H, Lilliehook IE. Comparison of specific gravity analysis of feline and canine urine, using five refractometers, to pycnometric analysis and total solids by drying. N Z Vet J 2015; 63: 254–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rishniw M, Bicalho R. Factors affecting urine specific gravity in apparently healthy cats presenting to first opinion practice for routine evaluation. J Feline Med Surg 2015; 17: 329–337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Watson ADJ, Lefebvre HE. Urine specific gravity. International Renal Interest Society. http://www.iris-kidney.com/education/urine_specific_gravity.aspx (2015, accessed October 16, 2015).

- 18. Ross LA, Finco DR. Relationship of selected clinical renal function tests to glomerular filtration rate and renal blood flow in cats. Am J Vet Res 1981; 42: 1704–1710. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hoskin JD, Turnwald GH, Kearney MT, et al. Quantitative urinalysis in kittens from four to thirty weeks after birth. Am J Vet Res 1991; 52: 1295–1299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Holan KM, Kruger JM, Gibbons SN, et al. Clinical evaluation of a leucocyte esterase test-strip for detection of feline pyuria. Vet Clin Path 1997; 26: 126–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Defontis M, Bauer N, Failing K, et al. Automated and visual analysis of commercial urinary dipsticks in dogs, cats and cattle. Res Vet Sci 2013; 94: 440–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. DiBartola SP. Clinical approach and laboratory evaluation of renal disease. In: Ettinger SJ, Feldman EC. (eds). Textbook of veterinary medicine. 7th ed. St Louis, MO: Saunders Elsevier, 2010, pp 1955–1969. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Heuter KJ, Buffington CAT, Chew DJ. Agreement between two methods for measuring urine pH in cats and dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1998; 213: 996–998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Grauer GF. Proteinuria. International Renal Interest Society. http://www.iris-kidney.com/education/proteinuria.aspx (2013, accessed October 16, 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hanzlicek AS, Roof CJ, Sanderson MW, et al. Comparison of urine dipstick, sulfosalicylic acid, urine protein-to-creatinine ratio, and a feline-specific immunoassay for detection of albuminuria in cats with chronic kidney disease. J Feline Med Surg 2012; 14: 882–888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Duffy ME, Specht A, Hill RC. Comparison between urine protein:creatinine ratios of samples obtained from dogs in home and hospital settings. J Vet Intern Med 2015; 29: 1029–1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Syme HM, Elliott J. Proteinuria. In: August JR. (ed). Consultations in feline internal medicine. 5th ed. St Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders, 2006, pp 415–422. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rossi G, Giori L, Campagnola S, et al. Evaluation of factors that affect analytic variability of urine-to-protein creatinine ratio determination in dogs. Am J Vet Res 2012; 73: 779–788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rossi G, Bertazzolo W, Dondi F, et al. The effect of inter-laboratory variability on the protein:creatinine (UPC) ratio in canine urine. Vet J 2015; 204: 66–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Welles EG, Whatley EM, Hall AS, et al. Comparison of Multistix PRO dipsticks with other biochemical assays for determining urine protein (UP), urine creatinine (UC) and UP:UC ratio in dogs and cats. Vet Clin Pathol 2006; 35: 31–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mardell EJ, Sparkes AH. Evaluation of a commercial in-house test kit for the semi-quantitative assessment of microalbuminuria in cats. J Feline Med Surg 2006; 8: 269–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wisnewski N, Clarke KB, Powell TD, et al. New data: prevalence of microalbuminuria in cats. https://www.heska.com/Documents/RenalHealthScreen/erd_datacat.aspx (2003, accessed November 14, 2015).

- 33. Kruth SA, Cowgill LD. Renal glucose transport in the cat. Proceedings of the ACVIM scientific forum, 1982, San Diego, USA, p 78. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Foster SF. Urinalysis – making sure it counts. Proceedings of the ISFM European congress; 2012 June 13–17, Budapest, Hungary, pp 79–86. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Fletcher JM, Behrend EN, Welles EG, et al. Glucose detection and concentration estimation in feline urine samples with the Bayer Multistix and Purina Glucotest. J Feline Med Surg 2011; 13: 705–711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Menrath V. Problem plumbing! FAB Journal 1998; 36: 21–24. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Rees CA, Boothe DM. Evaluation of the effect of cephalexin and enrofloxacin on clinical laboratory measurements of urine glucose in dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2004; 224: 1455–1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]