Abstract

Practical relevance Osteoarthritis (OA) is very common in the cat and in many cases is associated with significant long-term pain, which limits mobility and activity, and severely compromises the animal’s quality of life.

Clinical challenges The treatment of chronic arthritic pain is a major challenge and many analgesic drugs used in other species are not licensed, not available or not tested for use in the cat. Many older cats with painful OA have some degree of chronic kidney disease (CKD) and many clinicians are reluctant to use non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) in these animals because of the potential for nephrotoxicity.

Evidence base There are several publications that show that meloxicam is an effective NSAID for the cat and can be used long-term. It is easy to administer and there is published evidence that meloxicam can actually slow the progression of CKD in this species. Many other drugs are used to treat chronic pain in the cat but there is no documented evidence of their efficacy in OA. Unlike the dog, there is limited evidence for the effectiveness of omega-3 fatty acid-rich diets in managing feline OA and further work is required. There is no published data as yet for the usefulness or otherwise of nutraceuticals (glucosamine and chondroitin) in managing feline OA; studies in the authors’ clinic suggest some pain-relieving effect. Research into environmental enrichment as a way of improving quality of life in cats with painful OA is lacking, but it is an approach worth using where possible. Modifications to the environment (eg, provision of comfortable bedding and ramps) are also important.

Should we worry about treating feline osteoarthritis?

Even though it is now becoming, albeit slowly, accepted that cats do suffer with osteoarthritis (OA), many clinicians still appear to believe that cats with musculoskeletal pain do not need specific analgesic therapy. Their small size, coupled with the fact that they are not generally expected to perform strenuous activities or to go for walks with the owner, gives rise to the assumption that cats are able to adapt their lifestyle and cope with any discomfort. However, this is a dangerous assumption and the authors strongly believe that we should strive to relieve the pain associated with OA in cats and to improve their comfort and quality of life. In the past 10 years the percentage of cats in the USA over 6 years of age has increased from 24–47%, and cats over 15 years have increased from 5–14%. 1 The fact that the feline population is an ageing one, lends further weight to this welfare argument; given, as discussed in Part 1 of this article, that advancing age is the main risk factor for both increasing prevalence and severity of feline OA.

Are NSAIDs an option?

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are the mainstay of drug treatment of OA in other species, and there is much evidence to support their effectiveness in cats.2–7 However, the potential toxicity of these compounds deters many clinicians from routinely using them in older animals. NSAIDs act predominantly by blocking the inflammatory effects of prostaglandins through inhibition of the breakdown of arachidonic acid by cyclo-oxygenase (COX). There are two principal forms of COX – an endogenous form, COX-1, and an inducible form, COX-2. The endogenous form is responsible for the production of protective prostaglandins, which help to maintain the integrity of the gastric mucosa and vascular endothelium and to protect renal blood flow in times of circulatory crisis. COX-2 is produced as part of the inflammatory response and is responsible for producing inflammatory prostaglandins such as PGE2. It has thus been proposed that NSAIDs that preferentially or selectively inhibit COX-2 or are COX-1 sparing are preferable since they are potentially associated with fewer side effects.8,9 However, COX-1 does play an important part in the inflammatory process and pain perception, and COX-2 is important in the resolution of inflammation, is found in certain normal tissues such as the kidney and CNS, 9 and interestingly may play a role in the prevention and/or healing of duodenal damage.6,10,11

A comprehensive review of the use of NSAIDs in the cat has been published by Lascelles et al. 6 Although there are a few NSAIDs that are licensed for use in the cat (Table 1), only meloxicam is licensed for long-term use. Robenacoxib has recently been licensed for administration as a 6-day course for the cat; it is a COX-2 selective NSAID, with a very short plasma half-life, and has been shown specifically to target inflamed tissues. 12 Safety studies on the long-term administration of robenacoxib to cats, albeit healthy ones, have been published; no toxicologically significant effects were reported. 13 Ketoprofen has a 5-day licence in the cat for oral use. Tolfenamic acid is licensed as an antipyretic in the cat (3-day course) but is not licensed for musculoskeletal pain. Certain other NSAIDs have been used off-licence in the cat, but these are best avoided, particularly as meloxicam is generally safe and effective.

Table 1.

NSAID therapy in cats

| Drug | Dose | Indications/comments |

|---|---|---|

| Meloxicam (Metacam; Boehringer Ingelheim) | 0.1 mg/kg PO on day 1, then 0.05 mg/kg q24h PO | Easy to administer in food Dosing is more accurate if syringe is used Titrate to lowest effective dose Avoid initial loading dose if CKD is present COX-2 preferential |

| Robenacoxib (Onsior; Novartis) | 1–2 mg/kg PO q24h for up to 6 days | For use in acute pain and inflammation Plasma levels reduce relatively quickly but concentrations in inflamed tissues remain high Flavoured tablets – generally accepted COX-2 specific |

| Ketoprofen (Ketofen; Merial) | 1 mg/kg PO q24h for up to 5 days | Acute pain from musculoskeletal disorders |

| Tolfenamic acid (Tolfedine; Vétoquinol) | 4 mg/kg PO q24h for 3 days | Licensed only for treatment of fever and upper respiratory tract disorders |

These NSAIDs are all licensed for use in the cat in the UK

Note that the above comments relating to product licensing refer to the UK situation, and there may well be differences in other regions of the world that readers need to be aware of.

Use of meloxicam in the arthritic cat

Meloxicam has proven to be very effective for treating chronic pain in arthritic cats,2–6,14,15 and its liquid formulation makes accurate dosing relatively simple; it is palatable, and also well accepted when put in food. (More accurate dosing is achieved by using the syringe provided, rather than counting drops from the bottle, since the size of the drops can vary.) When given orally, meloxicam has a half-life of approximately 24 h, allowing effective once-daily dosing.6,7 Its bioavailability is approximately 80% when given orally, and 79% is eliminated in the faeces, with only 21% being eliminated in the urine, 7 resulting in less potential for nephrotoxicity. Meloxicam is known to be metabolised by oxidative pathways, and thus the relative low capacity for hepatic glucuronidation of exogenously administered drugs seen in the cat is less of a problem.16–18

The recommended dose of meloxicam, according to the manufacturer’s data sheet, is 0.1 mg/kg PO on day 1 and then 0.05 mg/kg q24h. However, there is considerable evidence that lower doses are effective in controlling arthritic pain and it is advisable to use the lowest effective dose, particularly when there is clinical or laboratory evidence of renal disease. In a study of 40 cats with osteoarthritic pain, each cat was given 0.1 mg PO, irrespective of body weight (equivalent to a dose range of 0.01–0.03 mg/kg), and owners subjectively assessed treatment efficacy as being good or excellent in 85% of cases. 14 In a study by Gowan et al where the median treatment duration was 527 days, the median maintenance dose after titration that maintained clinical improvement was 0.03 mg/kg, 15 which is much lower than the manufacturer’s recommended dose. Irrespective of the initial dose of meloxicam, it is always good practice to gradually reduce the dose that is being administered, either by reducing the dose level or by increasing the dose interval; the authors have used both approaches with success. The dose can be titrated according to the clinical response of the individual case.

Given it is mainly older cats that suffer from OA, routine blood and urine analyses are advisable to assess liver and kidney status before commencing NSAID therapy; monitoring of blood pressure is also recommended since inhibition of COX within the kidneys can exacerbate hypertension.9,19 Detection of any abnormalities is not a contra-indication for using the drug, but may affect the initial dose that is administered, and will influence the frequency of follow-up checks, and physical and laboratory examinations. If there is evidence of renal or hepatic disease, it is wise to start with a dose lower than the recommended dose (eg, 0.02–0.03 mg/kg); the dose can be gradually increased if required and if the clinical assessment allows.

Meloxicam has proven to be very effective for treating chronic pain in arthritic cats, and its liquid formulation makes accurate dosing relatively simple; it is palatable, and also well accepted when put in food.

Many cats with OA will also have some degree of chronic kidney disease (CKD), 15 which is a major concern for veterinarians and tends to make them very cautious and reluctant to use NSAIDs because of the possibility of precipitating acute renal failure. This has not been the authors’ experience and the above-mentioned study by Gowan and colleagues demonstrated that meloxicam might even have a beneficial effect on renal function in the older cat. 15 The group of cats with kidney disease that received meloxicam showed less of an increase in blood creatinine levels over time compared with cats with kidney disease that did not receive meloxicam. This effect may be indirect: improved mobility and overall quality of life subsequent to pain relief may result in a better appetite and increased water consumption, leading to an overall increase in calorie intake, better hydration and reduced tissue catabolism. The relief of pain could also reduce the animal’s ‘stress level’; stress has been shown to affect other disease processes such as idiopathic cystitis, 20 and conceivably stress might increase the severity of renal disease. Another possibility is that meloxicam has a direct anti-inflammatory effect on the kidney, leading to a reduction in ongoing interstitial inflammation and fibrosis that would otherwise cause further deterioration in renal function.

The median survival time for cats diagnosed with IRIS (International Renal Interest Society) stage 2 kidney disease is 1151 days and with stage 3 disease is 679 days. 21 Providing no evidence emerges that NSAIDs reduce this median survival time, it is preferable that cats with painful OA and CKD should live their remaining life in as little pain as possible.

Some important considerations when using NSAIDs in cats are highlighted below.

Considerations when using NSAIDs.

It is important to encourage adequate fluid intake in cats receiving NSAIDs and thus moist tinned or sachet food should be fed, particularly to animals on long-term therapy. If a cat receiving NSAIDs stops eating or drinking, the drug should be stopped immediately. The commonest side effect seen with NSAIDs is vomiting and diarrhoea, and has been reported in approximately 4% of cats receiving meloxicam.2,14 If these signs persist for more than a couple of days the drug should be stopped. It can be reintroduced after 3–5 days, preferably at a lower dose; alternatively, a different drug could be used. Gastrointestinal protectants (eg, omeprazole, 0.75–1.0 mg/kg PO q24h for maximum of 8 weeks; misoprostol, 5 µg/kg PO q8h) can be considered if gastrointestinal side effects are a persistent problem, although they are seldom necessary.

NSAIDs are highly protein-bound in the blood and thus care is always needed when they are given to a cat receiving other drugs where there might be competition for protein binding. Such competition could result in increased levels of NSAID in the blood with consequent adverse effects. These patients should be particularly carefully monitored. If administering a NSAID to a cat already receiving another drug, the dose of the NSAID should be halved; similarly if the cat is receiving a NSAID and another drug is given (eg, an antibiotic) then again the dose of the NSAID should be halved. The use of ACE inhibitors and/or diuretics together with NSAIDs has been shown in human medicine to significantly increase the risk of nephrotoxicity,22–24 and so extreme care is required if administering NSAIDs to cats on concomitant ACE inhibitor and/or diuretic therapy.

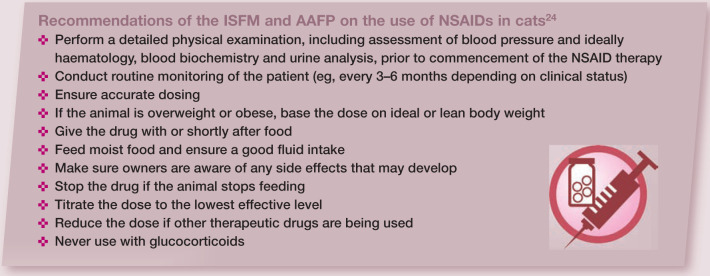

Recently, the International Society of Feline Medicine (ISFM) and the American Association of Feline Practitioners (AAFP) produced very useful guidelines, published in this journal, on the use of NSAIDs in the feline patient. 24 The main recommendations are summarised below.

Do other drug treatments have a role?

Multimodal analgesic therapy is now being introduced to the feline patient although this is still very much in its infancy and experience is lacking.24–26 The basis of this approach is to use a combination of drugs that all act at different levels of the pain pathway and thus will have a synergistic effect, hopefully improving pain control and possibly also enabling lower doses of individual drugs to be given, with less risk of side effects. Some of the drugs used to supplement NSAIDs (in humans, dogs and cats) are amantidine, amitriptyline, gabapentin and tramadol (Table 2).25–27 Some authorities also advocate the use of opioids (eg, butorphanol 0.1–0.4 mg/kg IV/IM/SC q2h or 0.2–1.0 mg/kg PO q6h; buprenorphine 0.01–0.03 mg/kg IM/IV/SC q6–8h, 0.01–0.03 mg/kg buccally q6–12h; and, in some countries, fentanyl patches 2–5 µg/kg/h q5–7 days), but the limitations of using these drugs in the treatment of chronic persistent pain are obvious. 27 These drugs are not licensed in the cat and their use must be in accordance with the prescribing cascade in the UK or other relevant prescribing legislation.

Table 2.

Other drugs sometimes used with NSAIDs for multimodal therapy

| Drug | Suggested dose | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Amantidine | 3–5 mg/kg PO q24h | No convenient size of capsule for cats Syrup available Not evaluated in the cat |

| Amitriptyline | 0.5–1.0 mg/kg PO q24h | Lethargy, weight gain, decreased grooming and transient cystic calculi reported |

| Gabapentin | 5–10 mg/kg PO q12–24h | Gradually reduce dose when withdrawing drug Appears effective, especially where sensitisation might be present Unpleasant taste |

| Tramadol | 1–2 mg/kg PO q12–24h | Very unpleasant taste Neurological side effects may occur May produce ‘opioid-like’ side effects |

NB Experience is lacking with these drugs in the cat. Thus they must be used cautiously (see Lascelles and Robertson) 26

Is there a benefit of feeding omega-3 fatty acids?

As with the dog, there are diets rich in omega-3 fatty acids (mainly found in fish oils) that are recommended for cats with OA. The omega-3 fatty acids most required by the cat are docosahexaenoic acid and alpha-linolenic acid. Not only are the absolute levels of these omega-3 fatty acids important but also the ratio of omega-3 to omega-6 fatty acids. There are publications showing the effectiveness of omega-3 rich diets in the dog, where randomised double-blind controlled clinical trials have shown that the diet improves weightbearing, as assessed by both objective and subjective measurements.28,29 The studies also showed that when used in combination with a NSAID (carprofen), the dose of the NSAID was reduced more quickly and to a lower level compared with the dose of NSAID required when a control diet was fed. 30

There is one published study evaluating an omega-3 rich diet in cats with degenerative joint disease, which showed that cats given the diet had improved activity levels compared with cats fed a control diet, as assessed by their owners; however, no differences in activity levels were detected with collar-mounted activity monitors. 31 There is also evidence that, contrary to popular belief, omega-3 rich diets can lead to weight loss.31–33

The authors most often use Hill’s feline j/d in combination with meloxicam. Obviously, when used with NSAIDs the moist form of the diet should be fed. It is the authors’ experience that many cats with chronic OA will improve when just having the diet on its own, although any improvement generally takes longer (6–8 weeks) compared with meloxicam alone (with which an improvement is often apparent within 7–10 days). These therapeutic diets generally contain other ingredients that might be beneficial, such as glucosamine and chondroitin (R Sul, D Chase, T Parkin and D Bennett, unpublished data). 34

The basis of multimodal analgesic therapy is to use a combination of drugs that all act at different levels of the pain pathway.

Are glucosamine and chondroitin supplements justified?

There are several preparations available containing glucosamine and chondroitin, usually with other additives such as minerals and antioxidants. Most of these are given orally and are referred to as nutraceuticals, although strictly this term covers any purified or synthesised substance that is given orally and which is involved in normal physiological functions. Both glucosamine and chondroitin are involved in the metabolism of cartilage matrix proteins and their use has often been justified on the grounds that they may help cartilage repair, or perhaps more likely, slow down its degradation in the osteoarthritic joint. However, there is anecdotal evidence that these preparations can reduce the pain associated with OA, an effect that is often reported within 6–8 weeks, suggesting that they may, in some way, be anti-inflammatory. It could be that by slowing the degradation of cartilage, the release of cartilage breakdown products (which are known to stimulate inflammation) is reduced.

The evidence from clinical studies carried out in both human and canine patients is contradictory. 34 Recently a randomised double-blind clinical trial in cats with OA comparing the effectiveness of meloxicam and a glucosamine/chondroitin supplement has been completed. The cats receiving the nutraceutical did improve with time but it took longer and the improvement was not to the same extent as that seen in the meloxicam group. Interestingly, when the two groups were given a placebo at 75 days and reassessed at 90 days, the improvement seen in the nutraceutical group was maintained for a significantly longer period compared with the meloxicam group (R Sul, D Chase, T Parkin and D Bennett, unpublished data).

A problem with these supplements is the lack of regulation and, in some cases, quality control. It is the authors’ opinion that products produced by reputable veterinary manufacturers and supplied through veterinary surgeons should always be used rather than the cheaper versions available through health stores and supermarkets. Although the exact ‘therapeutic’ dose of these products is unknown, the manufacturers’ recommended dose rates for these products result in higher amounts being administered compared with what is delivered by feeding prescription diets containing these supplements.

Modifying the environment in certain ways, when combined with appropriate analgesic therapy, can improve the cat’s physical and psychological welfare.

These products are generally very safe, and can be used either on their own or together with a NSAID, in which case they may help to lower the dose of the non-steroidal. Care must be taken with polysulphated products (mainly available in injectable form), which should not be used with NSAIDs since they have an anticoagulant effect which could theoretically prolong a gastrointestinal bleed produced by a NSAID. Pentosan polysulphate is the common injectable form; it does not have a licence for use in the cat in the UK, but is used in the cat, particularly in Australia. The oral administration of glucosamine and chondroitin has been associated with mild gastrointestinal upset in cats, although this is a rare side effect.

Weight reduction is useful, but can it be achieved?

Approximately 14% of older cats suffering from OA are obese. 2 Although pharmaceuticals have recently received approval for the treatment of weight loss in dogs (eg, dirlotapide; Slentrol, Pfizer), these drugs must not be given to cats because of the risk of hepatic lipidosis. Therefore, conventional strategies for weight management need to be applied.

Although challenging, a recent study showed that weight loss can be successfully achieved in client-owned cats through the use of low calorie diets, although the rate of weight loss was slower than predicted. 35 The main cause of owner non-compliance was begging by the cat. However, the study showed that begging behaviour was reduced when the diet was given in the dry form with high water-binding capacity fibre (not an option if the cat is also receiving NSAIDs). Altering the method of feeding (using pre-prepared portions) also helped.

Why is ‘environmental enrichment’ so key?

Because chronic arthritic pain seems to cause many significant behavioural changes in the cat, modifying the animal’s environment in certain ways, when combined with appropriate analgesic therapy, can help to overcome some of these and thus improve the physical and psychological welfare of the animal.25,26 A very useful review of environmental enrichment has been published in this journal. 36 Modifications need not be complex, as the following examples illustrate.

Steps and ramps It is generally accepted that the vertical dimension is very important to the cat. Therefore, steps or ramps can be provided to facilitate access to beds, sofas, window ledges, and so on, for cats with OA which are unwilling or unable to jump (Figure 1). Modification of cat flaps may also be required.

Bedding The provision of comfortable bedding is a simple but important requirement.

Security Cats are highly territorial animals and like to feel secure in their core territory (owner’s home) and the immediate outside territory. This can be improved by providing places to hide and, ideally, more than one access route. Major disturbances to the cat’s territory, such as the introduction of other pets, can cause anxiety and stress and make coping with chronic pain that much more difficult. Where possible, any changes that cannot be avoided should be introduced gradually.

Resources It is important to ensure the cat has easy access to food and water, and also to its litter tray. There should be at least one litter tray per cat in the household and the litter should be sufficiently deep. Litter trays need to be of a generous size for cats with mobility problems and sometimes this is better achieved by ‘purpose-built’ trays (Figure 2). More than one food bowl can be distributed throughout the core territory. This will encourage activity and provide mental stimulation. Hiding the cat’s bowl is also a way of providing physical and mental stimulation. Water bowls should be placed away from the food and more than one should be provided. Shallow water bowls are preferable. Scratching posts are another resource not to be overlooked (Figure 3).

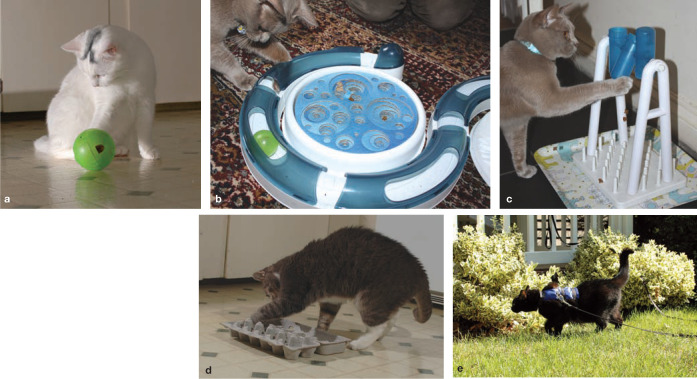

Interaction and exercise The owner should actively interact with the cat and provide opportunities for play and exploration during at least three sessions per day and for several minutes each session – again to encourage exercise and mental stimulation (Figure 4). Holding and stroking the cat, particularly around the head, is also to be encouraged, since this is known to release neurotransmitters that can improve the cat’s mood and its ability to cope with chronic pain. Grooming the cat on several different occasions during the day and for several minutes each time will have a similar effect (Figure 5).

Pheromonatherapy There is evidence that pheromonatherapy can reduce the impact of a stressed environment. 37 There are products available that contain feline facial pheromones (F3 fraction [Feliway; Sanofi] and F4 fraction [Felifriend; Sanofi]). These are provided as a spray that can be released into the environment or as a diffuser that plugs into an electrical socket.

Figure 1.

Arthritic cats find it difficult to jump and reach their favourite high points where they feel safe and content, be it a bed, sofa or window ledge (a). (b) Moving furniture to provide ‘stepped access’ will help. (a,b) Courtesy of Deb Givin (c,d) A variety of purpose-built steps and ramps are also commercially available. (c,d) ©2012 Foster & Smith, Inc. Reprinted as a courtesy and with permission from http://www.DrsFosterSmith.com

Figure 2.

The litter tray should be adapted so that it is easy for the cat to access and exit from and to comfortably position itself when urinating and defecating. This tray was made from a horticultural seedling tray. Courtesy of Sarah Heath

Figure 3.

Scratching posts, or in this case a home-made version comprising a cardboard scratch pad in a wooden box, can help to prevent excessive claw growth. Courtesy of Deb Givin

Figure 4.

Playing with different toys provides mental stimulation and encourages exercise, which helps strengthen muscles. A wide range of feeding devices and play toys is commercially available, such as the SlimCat treat ball (a), Catit Design Senses Play Circuit and Scratch Pad (b), and Catit Activity Turn Around (c). An egg carton ‘puzzle box’ containing kibble (d) is a simple and practical alternative. For the non-free-roaming cat, mental stimulation and exercise may be provided via lead walks (e), where appropriate. (a,d,e) Courtesy of Deb Givin. (b,c) Courtesy of Sarah Ellis

Figure 5.

Grooming activities often decline considerably in the older, arthritic cat. (a) Regular grooming by the owner is thus essential and not only promotes owner–cat interaction but also stimulates the release of endorphins and other mediators which can relax the cat and help it to cope better with its pain. (b) Grooming glove being used to give an older cat a grooming massage. (a,b) Courtesy of Deb Givin

Is physical therapy relevant to the cat?

This is an area that is growing in popularity as far as the canine patient is concerned and is just now beginning to be extended to the feline patient. This type of therapy is best designed and supervised by a trained animal physiotherapist (such as a member of the Association of Chartered Physiotherapists in Animal Therapy, www.acpat.co.uk). Range of motion and massage techniques can be taught to owners and these can help to alleviate the muscular pain that is often associated with OA, and improve joint mobility. This also promotes more interaction between the owner and the cat and helps to stimulate exercise and the release of mood-enhancing neurotransmitters. Other modalities such as shock wave therapy, laser therapy, heat and cold therapy, and even hydrotherapy, may be used.38–40

What is the role of surgery?

Total hip replacement is being performed in the cat, although to date there has been no published series of cases. Arthrodesis is another surgical treatment for a painful arthritic joint, although in the authors’ experience this is rarely used in the cat, principally because of multiple joint involvement, the specific joint affected (most often the elbow) and the age of the patient. Joint debridement and removal of osteochondral bodies may help to relieve pain,41,42 although in the authors’ experience these osteochondromas are often very extensive and not necessarily mobile within the joint, making their removal very difficult. Saline irrigation of an arthritic joint is known to produce clinical improvement in humans and dogs. 43

Is stem cell therapy a viable option?

Currently, autologous adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cell therapy is available in the USA, Australia and some mainland European countries. It has been used mainly in the dog for treating OA but it is also being used in cats (eg, Medivet promotional information, www.medivetblog.com). Under general anaesthesia, adipose tissue is surgically harvested and sent to a laboratory for processing or even processed within the veterinary practice if it has the necessary equipment. After processing, the cells are injected into the affected joint. Although there are undoubtedly stem cells present in the preparation, there are many other cells including a significant number of adipose cells. Clinical improvement has been reported in the dog, but the reasons for this are unclear.44,45 Such improvement is very unlikely to be due to any form of regeneration of joint tissues, but there might potentially be an anti-inflammatory effect since there are many immune cells and cytokines present in the preparation. One area of concern, however, is that adipose cells may produce cytokines and other adipokines, which can promote cartilage degradation.

In the authors’ view, the current therapy being offered is perhaps better described as ‘cell-based therapy’, rather than stem cell therapy. It is currently very expensive and certainly further studies are essential to see if it is truly relevant or effective.

Key points

Although there is now increasing awareness of feline OA, it is still a much underdiagnosed disease in general practice and there are likely to be many cats suffering chronic pain that would benefit from therapy.

The veterinary profession will be increasingly expected to diagnose and treat OA in cats, and management of this important condition must include attempting to improve the cat’s living environment and minimising stressful situations.

NSAIDs have an important role in reducing joint pain and currently meloxicam is the only NSAID licensed for long-term use in the cat, although not in all countries. Although renal disease is common in older cats with OA, it is not a contraindication for using NSAIDs; careful monitoring of cats receiving NSAIDs is, however, essential.

Diets rich in omega-3 fatty acids appear to reduce the inflammation and pain of OA and can be used together with NSAIDs. There is also a possible role for the nutraceuticals, glucosamine and chondroitin.

In some cases it can be difficult for the clinician to be sure of a diagnosis of OA, particularly if the physical examination is unrewarding and radiography is not possible. In these cases if there are behavioural changes consistent with arthritic pain then a therapeutic trial with a NSAID (or an omega-3 diet) can be tried and, if a response is seen, a tentative diagnosis of OA (or degenerative joint disease) is justified.

Acknowledgments

Grateful thanks to Deb Givin (The Cat Hospital, Maine, Oregon), Sarah Heath (Behavioural Referrals Veterinary Practice, UK), and Race Foster and Marty Smith (DrsFosterSmith.com) for providing images for this article.

Funding

The authors received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors for the preparation of this review article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Gunn-Moore D. Considering old cats [editorial]. J Small Anim Pract 2006; 47:430–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clarke SP, Bennett D. Feline osteoarthritis: a prospective study. J Small Anim Pract 2006; 47: 439–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bennett D, Morton CA. A study of owner observed behavioural and lifestyle changes in cats with musculoskeletal disease before and after analgesic therapy. J Feline Med Surg 2009; 11:997–1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lascelles BDX, Bernie HD, Roe S, et al. Evaluation of client-specific outcome measures and activity monitoring to measure pain relief in cats with osteoarthritis. J Vet Intern Med 2007; 21:410–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lascelles BD, Henderson AJ, Hackett IJ. Evaluation of the clinical efficacy of meloxicam in cats with painful locomotor disorders. J Small Anim Pract 2001; 42:587–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lascelles BD, Hardie EM, Robertson SA. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in cats: a review. Vet Anaesth Analg 2007; 34:228–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thoulon F, Narbe R, Johnston L, et al. Metabolism and excretion of oral meloxicam in the cat [abstract]. J Vet Intern Med 2009; 23:695. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bombardier C, Laine L, Reicin A, et al. Comparison of upper gastrointestinal toxicity of rofecoxib and naproxen in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. VIGOR Study Group. New Engl J Med 2000; 343: 1520–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bergh MS, Budsberg SC. The coxib NSAIDs: potential clinical and pharmacologic importance in veterinary medicine. J Vet Intern Med 2005; 19: 633–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wolfe MM, Lichstein DR, Singh G. Gastrointestinal toxicity of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. New Engl J Med 1999; 340: 1888–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wooten JG, Blikslager AT, Marks SL, Law JM, Graeber EC, Lascelles BD. Effect of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs with varied cyclooxygenase-2 selectivity on cyclooxygenase protein and prostanoid concentrations in pyloric and duodenal mucosa of dogs. Am J Vet Res 2009; 70: 1243–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.King JN, Dawson J, Esser RE, et al. Preclinical pharmacology of robenacoxib: a novel selective inhibitor of cyclooxygenase-2. J Vet Pharmacol Ther 2009; 32: 1–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.King JN, Hotz R, Reagan EL, Roth DR, Seewald W, Lees P. Safety of oral robenacoxib in the cat. J Vet Pharmacol Ther 2011; doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2885.2011.01320.x 10.1111/j.1365-2885.2011.01320.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gunew MN, Menrath VH, Marshall RD. Long-term safety, efficacy and palatability of oral meloxicam at 0.01–0.03 mg/kg for treatment of osteoarthritic pain in cats. J Feline Med Surg 2010; 10:235–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gowan RA, Lingard AE, Johnston L, Stansen W, Brown SA, Malik R. Retrospective case-control study of the effects of long-term dosing with meloxicam on renal function in aged cats with degenerative joint disease. J Feline Med Surg 2011; 13:752–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Court M, Greenblatt D. Molecular basis for deficient acetaminophen glucuronidation in cats. An interspecies comparison of enzyme kinetics in liver microsomes. Biochem Pharmacol 1997; 53: 1041–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Court M, Greenblatt D. Biochemical basis for deficient acetaminophen glucuronidation in cats. An interspecies comparison of enzyme constraint in liver microsomes. Biochem Pharmacol 1997; 49:446–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Court M, Greenblatt D. Molecular genetic basis for deficient acetaminophen glucuronidation by cats: UGT1A6 is a pseudogene and evidence for reduced diversity of expressed hepatic UGT1A isoforms. Pharmacogenetics 1997; 10:355–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khan KN, Venturini CM, Bunch RT, et al. Interspecies differences in renal localisation of cyclooxygenase isoforms: implications in nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-related nephrotoxicity. Toxicol Pathol 1998; 26: 612–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Westropp JL, Kass PH, Buffington CAT. Evaluation of the effects of stress in cats with idiopathic cystitis. Am J Vet Res 2006; 67:731–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boyd LM, Langstan C, Thompson K, et al. Survival in cats with naturally occurring chronic kidney disease (2000–2002). J Vet Intern Med 2008; 22:1111–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Whelton A, Hamilton CW. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: effects on kidney function. J Clin Pharmacol 1991; 31: 588–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Loboz K, Shenfield G. Drug combinations and impaired renal function – the ‘triple whammy’. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2005; 59: 239–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sparkes AH, Helene R, Lascelles BD, et al. ISFM and AAFP consensus guidelines: long-term use of NSAIDs in cats. J Feline Med Surg 2010; 12:519–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Robertson S, Lascelles BD. Long term pain in cats. How much do we know about this important welfare issue? J Feline Med Surg 2010; 12:188–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lascelles BD, Robertson S. DJD-associated pain in cats. What can we do to promote patient comfort? J Feline Med Surg 2010; 12: 200–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scherk M. Experiences in feline practice: incorporating NSAIDs in analgesic therapy. Proceedings of the International Society of Feline Medicine, pre-congress meeting, June 17, 2010; Amsterdam: 12–19. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roush JK, Cross AR, Renbergn WC, et al. Evaluation of the effects of dietary supplementation with fish oil omega-3 fatty acids on weight bearing in dogs with osteoarthritis. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2010; 236:67–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roush JK, Dodd CE, Fritsch DA, et al. Multicenter veterinary practice assessment of the effects of omega-3 fatty acids on osteoarthritis in dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2010; 236: 59–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fritsch DA, Allen TA, Dodd CE, et al. A multicenter study of the effect of dietary supplementation with fish oil omega-3 fatty acids on carprofen dosage in dogs with osteoarthritis. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2010; 236:535–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lascelles BDX, DePuy V, Thomson A, et al. Evaluation of a therapeutic diet for feline degenerative joint disease. J Vet Intern Med 2010; 24:487–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Madsen L, Petersen RK, Kristiansen K. Regulation of adipocyte differentiation and function by polyunsaturated fatty acids. Biochim Biophys Acta 2005; 1740:266–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brookes PS, Buckingham JA, Tenreiro AM, Hulbert AJ, Brand MD. The proton permeability of the inner membrane of liver mitochondria from ectothermic and endothermic vertebrates and from obese rats: correlation with standard metabolic rate and phospholipids fatty acid composition. Comp Biochem Physiol B Biochem Mol Biol 1998; 119:325–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reginster J-Y, Derolsy R, Rouati LC, et al. Long-term effects of glucosamine sulphate on osteoarthritis progression; a randomised, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Lancet 2001; 357: 251–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bissot T, Servet E, Vidal S, et al. Novel dietary strategies can improve the outcome of weight loss programmes in obese client-owned cats. J Feline Med Surg 2010; 12:104–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ellis S. Environmental enrichment. Practical strategies for improving feline welfare. J Feline Med Surg 2009; 11:901–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Griffith CA, Steigerwald ES, Buffington T. Effects of a synthetic facial hormone on behaviour of cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2000; 217: 1154–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lindley S. Introduction to physical therapies. In: Watson P, Lindley S, eds. BSAVA manual of canine and feline rehabilitation, supportive and palliative care. Gloucester: BSAVA Publications, 2010: 85–89. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sharp B. Physiotherapy and physical rehabilitation. In: Watson P, Lindley S, eds. BSAVA manual of canine and feline rehabilitation, supportive and palliative care. Gloucester: BSAVA Publications, 2010: 90–113. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lindley S, Smith H. Hydrotherapy. In: Watson P, Lindley S, eds. BSAVA manual of canine and feline rehabilitation, supportive and palliative care. Gloucester: BSAVA Publications, 2010: 114–23. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Staiger BA, Beale BS. Use of arthroscopy for debridement of the elbow joint in cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2005; 226:401–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tan C, Allan G, Barfield D, Krockenberger MB, Howlett R, Malik R. Synovial osteochondroma involving the elbow of a cat. J Feline Med Surg 2010; 12:412–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bennett D. Canine and feline osteoarthritis. In: Ettinger SJ, Feldman EC, eds. Textbook of veterinary internal medicine. Diseases of the dog and cat. 7th edn. Missouri: Saunders, Elsevier, 2010: 750–61. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Black LL, Gaynor J, Adams C, et al. Effect of intraarticular injection of autologous adipose-derived mesenchymal stem and regenerative cells on clinical signs of chronic osteoarthritis of the elbow joint in dogs. Vet Ther 2008; 9: 192–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Black LL, Gaynor J, Gahring D, et al. Effect of adipose-derived mesenchymal stem and regenerative cells on lameness in dogs with chronic osteoarthritis of the coxofemoral joints: a randomized, double-blinded, multicenter, controlled trial. Vet Ther 2007; 8: 272–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lindley S. Acupuncture in palliative and rehabilitative medicine. In: Watson P, Lindley S, eds. BSAVA manual of canine and feline rehabilitation, supportive and palliative care. Gloucester: BSAVA Publications, 2010: 123–30. [Google Scholar]