Abstract

Overview:

Dermatophytosis, usually caused by Microsporum canis, is the most common fungal infection in cats worldwide, and one of the most important infectious skin diseases in this species. Many adult cats are asymptomatic carriers. Severe clinical signs are seen mostly in kittens or immunosuppressed adults. Poor hygiene is a predisposing factor, and the disease may be endemic in shelters or catteries. Humans may be easily infected and develop a similar skin disease.

Infection:

Infectious arthrospores produced by dermatophytes may survive in the environment for about a year. They are transmitted through contact with sick cats or healthy carriers, but also on dust particles, brushes, clothes and other fomites.

Disease signs:

Circular alopecia, desquamation and sometimes an erythematous margin around central healing (‘ringworm’) are typical. In many cats this is a self-limiting disease with hair loss and scaling only. In immunosuppressed animals, the outcome may be a multifocal or generalised skin disease.

Diagnosis:

Wood’s lamp examination and microscopic detection of arthrospores on hairs are simple methods to confirm M canis infection, but their sensitivity is relatively low. The gold standard for detection is culture on Sabouraud agar of hairs and scales collected from new lesions.

Disease management:

In shelters and catteries eradication is difficult. Essential is a combination of systemic and topical treatments, maintained for several weeks. For systemic therapy itraconazole is the drug of choice, terbinafine an alternative. Recommended topical treatment is repeated body rinse with an enilconazole solution or miconazole with or without chlorhexidine. In catteries/shelters medication must be accompanied by intensive decontamination of the environment.

Vaccination:

Few efficacy studies on anti-M canis vaccines (prophylactic or therapeutic) for cats have been published, and a safe and efficient vaccine is not available.

Agent properties

In contrast to single-celled yeasts, dermatophytes (‘skin plants’) are complex fungi growing as hyphae and forming a mycelium. About 40 species belonging to the genera Microsporum, Trichophyton and Epidermophyton are considered as dermatophytes. Over 90% of feline dermatophytosis cases worldwide are caused by Microsporum canis. 1 Others are caused by M gypseum, T mentagrophytes, T quinckeanum, T verrucosum or other agents. With the exception of M gypseum, all of these agents produce proteolytic and keratolytic enzymes that enable them to utilise keratin as the sole source of nutrition after colonisation of the dead, keratinised portion of epidermal tissue (mostly stratum corneum and hairs, sometimes nails).

Dermatophytes produce arthrospores, which are highly resistant, surviving in a dry environment for 12 months or more [EBM grade III]. 2 In a humid environment, however, arthrospores are short-lived. High temperatures (100°C) destroy them quickly. Arthrospores adhere very strongly to keratin.

Depending on the source of infection and reservoirs, dermatophyte species are classified into zoophilic, sylvatic, geophilic and anthropophilic fungi.

Epidemiology

Dermatophytosis is worldwide the most common fungal infection of cats and one of the most important infectious skin diseases in this species. It may be transmitted to other animal species, and is also an important zoonosis.

M canis is a typical zoophilic dermatophyte. It was generally thought that subclinical infections are very common in cats, especially in longhaired animals over 2 years of age. However, in many groups the prevalence is relatively low. Therefore, M canis should not be considered part of the normal fungal flora of cats and its isolation from a healthy animal indicates either subclinical infection or fomite carriage. 1

Arthrospores are transmitted through contact with sick or subclinically infected animals, mainly cats, but also dogs or other species. In sick animals, the infected hair shafts are fragile and hair fragments containing arthrospores are very efficient in spreading infection. In addition, uninfected cats can passively transport arthrospores on their hair, thereby acting as a source of infection. Risk factors include: introducing new animals into a cattery, cat shows, shelters, mating, etc. Indirect contact is very important too; transmission may occur via contaminated collars, brushes, toys, environments, etc. Arthrospores are easily spread on dust particles, even to rooms without access for cats.

Outdoor cats, especially in rural areas, can be exposed by digging to M gypseum, a geophilic fungus living in soil. Cats may be infected with T mentagrophytes or T quinckeanum through contact with small rodents, and with T verrucosum through contact with cattle.

Pathogenesis

Healthy skin acts as an effective barrier against fungal invasion. The increased rate of regeneration of epidermal cells in response to the dermatophyte, with the consequent removal of fungus from the skin surface, is another protective mechanism. As dermatophytes cannot penetrate healthy skin, many cats are merely passive carriers of the arthrospores or remain subclinically infected. Whether such an infection will lead to clinical disease depends on many factors. Predisposing factors to disease include: a young age (first 2 years of life), immunosuppression (including immunosuppressive treatment), other diseases, nutritional deficits (especially proteins and vitamin A), high temperature and high humidity. 1

Very important for the facilitation of infection is any kind of skin trauma resulting from increased moisture, injury by ectoparasites or scratches due to pruritus, playing or aggressive behaviour, clipping, etc. In general, poor hygiene is a predisposing factor. In overcrowded feline groups, social stress may play an important role. This can make eradication of ringworm very difficult in catteries or shelters infected with M canis.

The potential immunosuppressive effect of feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV) and feline leukaemia virus (FeLV) on the prevalence of fungal infection has been investigated. The higher prevalence of M canis in FIV-infected animals compared with normal cats reported in one survey 3 was not observed by another group. 4 It has been suggested that any association may be related to differences in the environment rather than to the retroviral status of the cats. 5

The incubation period of ringworm caused by M canis is 1–3 weeks. During this time, hyphae grow along the hair shafts through the stratum corneum to the follicles where they produce spores that form a thick layer around the hair shafts. As dermatophytes are susceptible to high temperatures, they cannot colonise deeper parts of the skin or the follicle itself. Therefore, the hair grows normally but breaks easily near the skin surface, resulting in hair loss. Several metabolic products of the fungus may induce an inflammatory response in the skin, and may be observed mainly around the infected area, forming sometimes ring-like lesions with central areas of healing and papules on the periphery (‘ringworm’).

In many immunocompetent cats living in hygienic conditions these lesions are limited (eg, to the head) and disappear after several weeks. In immunosuppressed animals, the outcome may be a multifocal or generalised skin disease with secondary bacterial infections. On rare occasions, a marked inflammatory reaction to hyphae induces a nodular granulomatous reaction involving dermis and draining on the skin surface. These so-called pseudomycetomas are more often seen in Persian cats, sometimes concurrently with classical lesions.

The pathogenesis of other dermatophyte infections is similar to that described above.

Immunity

Naturally occurring ringworm is rarely recurrent, suggesting an effective and long-lasting immunity. Experimental studies confirm that animals express increased resistance to subsequent challenge by the homologous fungus. Reinfections may occur, but require a much greater number of spores, and usually these subsequent infections are cleared more rapidly. 1 It has been suggested that for the development of full immunity, the infection must run its entire natural course, as in cats whose infection was aborted with antifungal treatment the delayed type hypersensitivity reactions were often weaker. 6

Although dermatophyte infection is confined to the superficial keratinised tissues, a humoral and cellular immune response is induced. Prominent activation of T helper type 2 (Th2) cells and the corresponding cytokine profile leads to antibody formation followed by chronic disease, whereas activation of Th1 cells stimulates a cell-mediated response characterised by interferon-γ, and interleukins 12 and 2, and leads to recovery.1,7 Such cats are protected against reinfection. 8 The role of the humoral response in dermatophytosis is unclear, although antibodies could have a fungistatic effect by means of opsonisation and complement activation. 9

Clinical signs

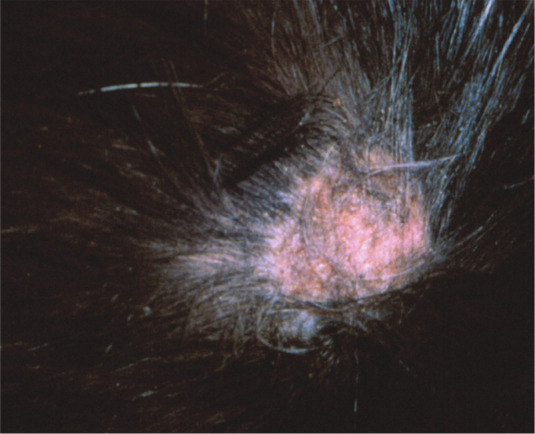

In many cats, dermatophytes cause a mild, self-limiting infection with hair loss and scaling (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

In some cats, especially immunocompetent adults, the only sign of dermatophytosis may be scaling. Courtesy of Tadeusz Frymus

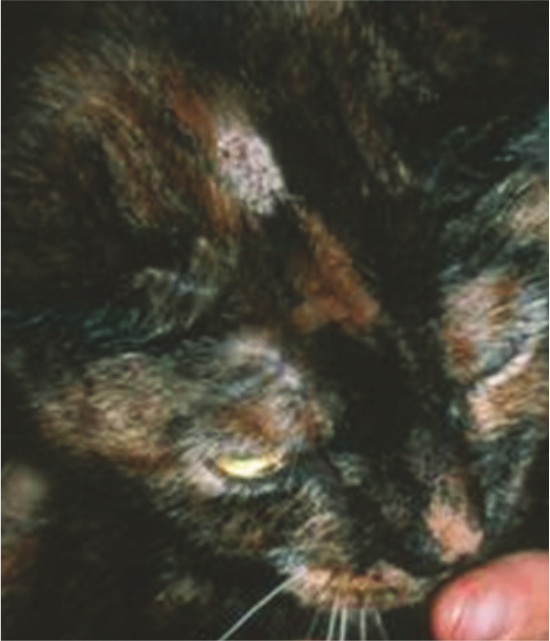

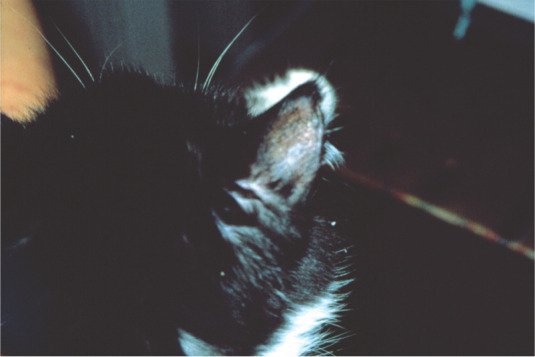

The typical presentation of ringworm in cats is regular and circular alopecia (Figure 2), with hair breakage, desquamation and sometimes an erythematous margin and central healing.1,10 The lesions are sometimes very small, but occasionally may have a diameter of 4–6 cm. Lesions may be single or multiple, and are localised mostly on the head (Figure 3) but also on any part of the body, including the distal parts of the legs and the tail. Young cats, in particular, display lesions localised at first to the bridge of the nose and then extending to the temples, the external sides of the pinnae and auricular margins (Figure 4). Multiple lesions may coalesce. Pruritus is variable, generally mild to moderate, and usually no fever or loss of appetite is observed.1,10

Figure 2.

Circular alopecia caused by M canis infection. Courtesy of Tadeusz Frymus

Figure 3.

On many occasions dermatophytosis lesions start on the head. Courtesy of International Cat Care (formerly Feline Advisory Bureau)

Figure 4.

External sides of the pinnae may also be affected by dermatophytosis. Courtesy of Tadeusz Frymus

In some cats, dermatophytosis can present as a papulocrustous dermatitis (‘miliary dermatitis’) affecting mainly the dorsal trunk.

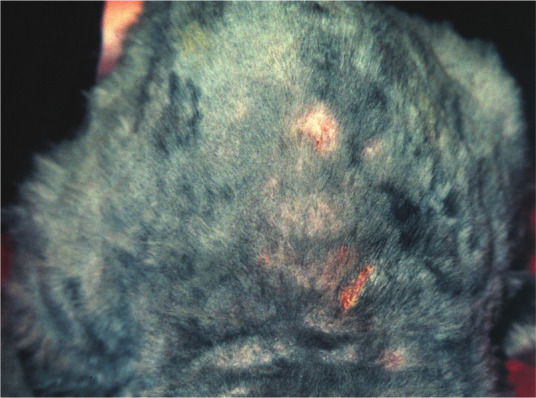

In immunosuppressed cats, extensive lesions with secondary bacterial involvement are sometimes associated with chronic ringworm. Such patients demonstrate atypical, large alopecic areas, erythema, pruritus, exudation and crusts (Figure 5). At this stage, dermatophytosis may mimic other dermatological conditions. Typical signs may be still visible at the margins of the lesions.

Figure 5.

In some cats, particularly immunocompromised ones, the outcome of dermatophytosis may be a multifocal or generalised skin disease. Courtesy of International Cat Care (formerly Feline Advisory Bureau)

A rare outcome is onyxis and perionyxis and, exceptionally, nodular granulomatous dermatitis (pseudomycetoma) with single or multiple cutaneous nodules, firm and not painful on palpation. 11 Fistulisation of these nodules is possible. Pseudomycetoma occurring as abdominal masses may be a rare complication of laparotomy in animals with cutaneous dermatophytosis. 12

Diagnosis

As dermatophytosis can produce lesions similar to many feline skin diseases, it should be considered in all cats with any cutaneous condition. If possible, dermatophyte diagnosis should be undertaken before any treatment.

An inexpensive and simple screening tool for M canis infection is the Wood’s lamp examination. However, it is not very sensitive: only about 50% of M canis strains fluoresce and other dermatophytes do not fluoresce at all. 13 Furthermore, debris, scale, lint and topical medications (eg, tetracycline) can produce false-positive results. Thus, Wood’s lamp findings should be confirmed by other methods.

Direct microscopic examination is another simple and rapid method to detect dermatophytes on hairs or scales. It is recommended to pluck hairs for this purpose under Wood’s lamp illumination, or from the edge of a lesion. The sample should be cleared with 10–20% potassium hydroxide solution before examination. There are a number of techniques to improve the visualisation of fungal elements on the hair shafts. 1 Hairs or hair fragments with hyphae and arthrospores are thicker, with a rough and irregular surface. However, direct microscopic examination may give false-positive results, especially if saprophytic fungal spores are present or debris is interpreted as fungal elements. Also, the sensitivity of this technique is relatively poor and has been assessed as 59%. 14 Higher sensitivity (76%) has been achieved by fluorescence microscopy with calcafluor white – a special fluorescent stain that binds strongly to structures containing cellulose and chitin. 13

Culture on Sabouraud dextrose agar or other media is the gold standard for the detection of dermatophytes. This method is very sensitive and can determine the species. Samples (hairs, scales) should be collected from the margin of new lesions after gently swabbing with alcohol to reduce contamination. If a subclinical infection or passive carriage is suspected, brushing for 5 mins with a sterile brush is the best method for collecting sample material. A brand new toothbrush is mycologically sterile. 1 Several in-house dermatophyte test media (DTM) based on colour change are available commercially. However, few attempts have been made to evaluate the performance of such media with veterinary samples. 10 Therefore, suspect colonies must be examined microscopically to confirm the presence of a fungus. 1

Polymerase chain reaction has been proposed for the detection of M canis sequences in suspected material from animals. 15

Disease management

In immunocompetent cats, isolated lesions disappear spontaneously after 1–3 months and may not require medication. However, treatment of such cases will reduce the disease course as well as the risk for other animals and humans, and contamination of the environment.

Topical treatment is generally less effective in cats compared with humans due to poor penetration of the medicines through the hair coat, lack of tolerance of this treatment by many cats and the possible existence of unnoticed small lesions (Figure 6). Thus, therapeutic measures should include a combination of systemic and topical treatment, maintained for at least 10 weeks. Generally, cats should be treated not only until the lesions completely disappear, but until the dermatophyte can no longer be cultured from the hairs on at least two sequential brushings 1–3 weeks apart.

Figure 6.

Some dermatophytosis lesions may become visible only after clipping. Courtesy of Tadeusz Frymus

In catteries and shelters, dermatophyte infection is very difficult, time-consuming and expensive to eradicate. Good compliance by the owner is therefore essential. A treatment programme is necessary, together with complete separation of infected and uninfected animals and intensive decontamination of the environment. This will necessitate interruption of breeding programmes and shows. All animals in the cattery should be treated. A far less preferable alternative is to divide the cats into groups and treat according to infection status. Special hygiene measures should be taken when handling infected animals in order to prevent infection of humans (gloves, disinfection of cat scratches or any other injury).

Topical therapy

In cats with a limited number of lesions, hairs should be clipped away from the periphery of lesions incorporating a wide margin. Clipping should be gentle to avoid spreading the infection due to microtrauma. Spot treatment of lesions may be of limited efficacy; instead, whole body shampooing, dipping or rinsing is recommended. In patients with generalised disease, longhaired cats and for cattery decontamination, clipping the entire cat is useful to make topical therapy application easier and to allow for better penetration of the drug. This approach also limits the spread of the spores into the environment, to people and to other animals. The entire hair coat, including whiskers, should be gently clipped and all infected hairs should be wrapped and disinfected before disposal. Chemical or heat sterilisation of instruments is essential. Cats should not be clipped in veterinary clinics to avoid environmental contamination. The best place for clipping is in the cat’s own household, where the environment is already contaminated.

Topical antifungal drugs differ widely in their efficacy. One of the most effective procedures is a whole body treatment with a 0.2% enilconazole solution performed twice weekly. 1 Local or general side effects are very seldom reported provided that grooming is prevented (Elizabethan collar) until the cat is dry. 16 Very effective is also 2% miconazole with or without 2% chlorhexidine as a twice weekly body rinse or shampoo. 1 In the USA, lime-sulphur solution is commonly used.

Systemic therapy

Itraconazole

Though relatively expensive, itraconazole is currently the preferred drug in feline dermatophytosis and is licensed for this indication. 1 It is comparable (or superior) in efficacy to ketoconazole or griseofulvin and is much better tolerated by cats. The only adverse reaction occasionally reported is anorexia. The embryotoxicity and teratogenicity of itraconazole also seems to be lower than that of ketoconazole. Nevertheless, its administration in pregnancy is not recommended. Use in kittens as young as 6 weeks is possible.

Most veterinary dermatologists will use itraconazole as so-called pulse therapy, which is also suggested by the manufacturer. This protocol is effective and also reduces the cost of treatment. A pulse administration of 5 mg/kg/day for 1 week, every 2 weeks for 6 weeks has been suggested. 17 Another study demonstrated that there were sufficient levels of itraconazole in the plasma and the fur of cats with ringworm that had been given three cycles of treatment consisting of 1 week with treatment (5 mg/kg) and 1 week without. A 25–30% reduction in levels was observed after the week without treatment, but the concentrations were still high enough even 2 weeks after the last administration [EBM grade IV]. 18 These data illustrate that such a treatment schedule (3 x 7 days of dosing) provides actual coverage of at least 7 weeks.

Terbinafine

An alternative is terbinafine administered orally 30–40 mg/kg once daily.1,11 It seems also suitable for pulse therapy. After administration lasting 14 days, terbinafine persisted in the hair of cats at inhibitory concentrations for 5.3 weeks [EBM grade III]. 19 Occasional vomiting and intensive facial pruritus has been observed as side effects.

Ketoconazole

Ketoconazole has been used orally at 2.5–5 mg/kg twice daily. However, cats are relatively susceptible to side effects with this drug, which include liver toxicity, anorexia, vomiting, diarrhoea and suppression of steroid hormone synthesis. Ketoconazole is also contraindicated in pregnant animals.

Griseofulvin

In some countries, griseofulvin is still used. However, it is not now generally recommended as more safe and effective preparations are available. It is administered orally for at least 4–6 weeks at 25–50 mg/kg q12–24h. Griseofulvin is poorly soluble in water and micronised formulation as well as administration with fatty meals enhance absorption. Adverse reactions include anorexia, vomiting, diarrhoea and bone marrow suppression, particularly in Siamese, Himalayan and Abyssinian cats. The use of griseofulvin is contraindicated in kittens younger than 6 weeks of age and in pregnant animals as the compound is teratogenic, particularly during the first weeks of gestation. There are a few reports suggesting that FIV infection predisposes cats to griseofulvin-induced bone marrow suppression. Therefore, cats should be tested for this infection prior to therapy. If griseofulvin is chosen, a complete blood count should be carried out monthly to detect possible bone marrow suppression.

Lufenuron

Lufenuron is a chitin synthesis inhibitor, used for the prevention of flea infestations in dogs and cats. As chitin is also a component of the fungal cell wall, some antifungal activity had been anticipated. However, studies in cats have not demonstrated antifungal effect and lufenuron is not recommended for the treatment of dermatophytosis. 1

Other options

In cattle and fur-bearing animals, immunotherapy with anti-dermatophyte vaccines is believed to reduce the lesions and to accelerate their disappearance. Although M canis vaccines have been marketed for treatment of affected cats, controlled studies demonstrating efficacy of this procedure in cats are hard to find. Results of a placebo-controlled double-blind study performed on 55 cats with severe dermatophytosis caused by M canis or T mentagrophytes have been published. 20 An inactivated vaccine containing antigens of M canis, M canis var distortum, M canis var obesum, M gypseum and T mentagrophytes was given three times intramuscularly to sick animals. A trend of improvement in all cats following therapeutic vaccination was observed, although this improvement was not significantly different from that seen in the placebo-treated cats.

Environmental decontamination

Thorough vacuuming and mechanical cleaning is essential to remove infective material (no visible hairs should be present), especially in households with one or a few cats where disinfection is impractical and unnecessary. However, in catteries or shelters, disinfection is very important. Most disinfectants labelled as ‘antifungal’ are fungicidal against mycelial forms of the dermatophyte or macroconidia but not against arthrospores. Most efficient against arthrospores are 1:33 lime-sulphur, 0.2% enilconazole, and 1:10 to 1:100 household chlorine bleach. 1 All surfaces should be cleaned with one of these solutions. An enilconazole smoke fumigant formulation is available in many European countries.

Detailed decontamination procedures, as well as the management of infected catteries and shelters during treatment, are described elsewhere.1,21

Footnotes

Funding: The authors received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors for the preparation of this article. The ABCD is supported by Merial, but is a scientifically independent body.

The authors do not have any potential conflicts of interest to declare.

Key Points

Dermatophytosis, caused usually by M canis, is the most common fungal infection in cats and one of the most important infectious skin diseases in this species.

M canis produces arthrospores that may remain infective for about a year and are easily transmitted by direct contact or by fomites to cats, other animal species and humans.

Many cats are infected subclinically or are fomite carriers of the arthrospores.

Dermatophytosis may be endemic in groups of cats, especially in poor environmental conditions, and the eradication of the disease is very difficult in such cases.

Circular alopecia, desquamation and sometimes an erythematous margin around central healing (‘ringworm’) are typical lesions of this chronic skin disease.

In many cats it is a self-limiting disease with hair loss and scaling only. In young animals and immunosuppressed adults, the outcome may be a multifocal or generalised skin disease.

The gold standard for the detection of dermatophytes is culture on Sabouraud agar. Wood’s lamp examination and microscopic detection of arthrospores on hairs are much less sensitive.

In severe cases systemic and topical therapy must be combined and maintained for several weeks. In catteries and shelters, medication must be accompanied by intensive decontamination of the environment.

For systemic therapy itraconazole is the drug of choice.

Recommended topical treatment is repeated body rinsing with an enilconazole solution or miconazole with or without chlorhexidine.

As a safe and efficient vaccine for cats is still not available, the ABCD does not recommend vaccination.

References

- 1. Moriello KA, DeBoer DJ. Dermatophytosis. In: Greene CE. (ed). Infectious diseases of the dog and cat. 4th ed. St Louis: Elsevier, 2012, pp 588–602. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sparkes AH, Werrett G, Stokes CR, Gruffyd-Jones TJ. Microsporum canis: inapparent carriage by cats and the viability of arthrospores. J Small Anim Pract 1994; 35: 397–401. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mancianti F, Giannelli C, Bendinelli M, Poli A. Mycological findings in feline immunodeficiency virus-infected cats. J Med Vet Mycol 1992; 30: 257–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sierra P, Guillot J, Jacob H, Bussiéras S, Chermette R. Fungal flora on cutaneous and mucosal surfaces of cats infected with feline immunodeficiency virus or feline leukemia virus. Am J Vet Res 2000; 61: 158–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mignon BR, Losson B. Prevalence and characterization of Microsporum canis carriage in cats. J Med Vet Mycol 1997; 35: 249–256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Moriello KA, DeBoer DJ, Greek J, Kukl K, Fintelman M. The prevalence of immediate and delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions to Microsporum canis antigens in cats. J Feline Med Surg 2003; 5: 161–166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sparkes AH, Stokes CR, Gruffydd-Jones TJ. Experimental Microsporum canis infection in cats: correlation between immunological and clinical observations. J Med Vet Mycol 1995; 33: 177–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sparkes AH, Stokes CR, Gruffydd-Jones TJ. Humoral immune responses in cats with dermatophytosis. Am J Vet Res 1993; 54: 1869–1873. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sparkes AH, Stokes CR, Gruffydd-Jones TJ. SDS-PAGE separation of dermatophyte antigens, and Western immunoblotting in feline dermatophytosis. Mycopathologia 1994; 128: 91–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chermette R, Ferreiro L, Guillot J. Dermatophytoses in animals. Mycopathologia 2008; 166: 385–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Nuttall TJ, German AJ, Holden SL, Hopkinson C, McEwan NA. Successful resolution of dermatophyte mycetoma following terbinafine treatment in two cats. Vet Dermatol 2008; 19: 405–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Black SS, Abernethy T, Tyler JW, Thomas MW, Garma-Avia, Jensen HE. Intra-abdominal dermatophytic pseudomycetoma in a Persian cat. J Vet Intern Med 2001; 15: 245–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sparkes AH, Werrett G, Stokes CR, Gruffydd-Jones TJ. Improved sensitivity in the diagnosis of dermatophytosis by fluorescence microscopy with calcafluor white. Vet Rec 1994; 134: 307–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sparkes AH, Gruffydd-Jones TJ, Shaw SE, Wright AI, Stokes CR. Epidemiological and diagnostic features of canine and feline dermatophytosis in the United Kingdom from 1956 to 1991. Vet Rec 1993; 133: 57–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nardoni S, Franceschi A, Mancianti F. Identification of Microsporum canis from dermatophytic pseudomycetoma in paraffin-embedded veterinary specimens using a common PCR protocol. Mycoses 2007; 50: 215–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hnilica KA, Medleau L. Evaluation of topically applied enilconazole for the treatment of dermatophytosis in a Persian cattery. Vet Dermatol 2002; 13: 23–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Colombo S, Cornegliani L, Vercelli A. Efficacy of itraconazole as combined continuous/pulse therapy in feline dermatophytosis: preliminary results in nine cases. Vet Dermatol 2001; 12: 347–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Vlaminck KMJA, Engelen MACM. Itraconazole: a treatment with pharmacokinetic foundations. Vet Dermatol 2004; 15: 8. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Foust AL, Marsella R, Akucewich LH, Kunkle G, Stern A, Moattari S, et al. Evaluation of persistence of terbinafine in the hair of normal cats after 14 days of daily therapy. Vet Dermatol 2007; 18: 246–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Westhoff DK, Kloes M-C, Orveillon FX, Farnow D, Elbers K, Mueller RS. Treatment of feline dermatophytosis with an inactivated fungal vaccine. Open Mycology J 2010; 4: 10–17. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Carlotti DN, Guinot P, Meissonnier E, Germain PA. Eradication of feline dermatophytosis in a shelter: a field study. Vet Dermatol 2009; 21: 259–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lund A, DeBoer DJ. Immunoprophylaxis of dermatophytosis in animals. Mycopathologia 2008; 166: 407–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. DeBoer DJ, Moriello KA. The immune response to Microsporum canis induced by fungal cell wall vaccine. Vet Dermatol 1994; 5: 47–55. [Google Scholar]

- 24. DeBoer DJ, Moriello KA, Blum JL, Volk LM, Bredahl LK. Safety and immunologic effects after inoculation of inactivated and combined live-inactivated dermatophytosis vaccines in cats. Am J Vet Res 2002; 63: 1532–1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]