Abstract

Overview:

Papillomaviruses are epitheliotropic and cause cutaneous lesions in man and several animal species, including cats.

Infection:

Cats most likely become infected through lesions or abrasions of the skin. Species-specific viruses have been detected but human and bovine related sequences have also been found, suggesting cross-species transmission.

Clinical signs:

In cats, papillomaviruses are associated with four different skin lesions: hyperkeratotic plaques, which can progress into Bowenoid in situ carcinomas (BISCs) and further to invasive squamous cell carcinomas (ISCCs); cutaneous fibropapillomas or feline sarcoids; and cutaneous papillomas. However, papillomaviruses have also been found in normal skin.

Diagnosis:

Papillomavirus-induced skin lesions can be diagnosed by demonstration of papillomavirus antigen in biopsies of skin lesions, or detection of papillomavirus-like particles by electron microscopy and papillomavirus DNA by polymerase chain reaction (PCR).

Treatment:

Spontaneous regression might be expected. In cases of ISCC, complete excision should be considered if possible.

Virus

Papillomaviruses are small viruses containing circular double-stranded DNA and belonging to the family Papillomaviridae, which contains 30 genera.

Epidemiology

Papillomaviruses have been detected in several animal species and in man as a cause of cutaneous lesions. 1 In each host different papillomavirus types exist, which is also true for cats. 2 The viruses tend to be species-specific, but sequences related to bovine and human papillomaviruses have been found in cats, suggesting cross-species transmission.3,4 Papillomavirus infection has also been detected in other felids including the Florida panther subspecies of cougar (Puma concolor coryi), bobcat (Lynx rufus), Asian lion (Panthera leo persica), snow leopard (Panthera uncia) and clouded leopard (Neofelis nebulosa). 5

Pathogenesis

Papillomaviruses are epitheliotropic; infections usually occur through lesions or abrasions of the skin. Initially, the basal cells of the stratum germinativum are infected, which leads to hyperplasia and delayed maturation of cells in the stratum spinosum and granulosum. In the basal cells only early gene expression occurs, whereas viral protein synthesis and virion assembly occurs in terminally differentiated cells of the stratum spinosum and, more specifically, the stratum granulosum. Virus is present in the differentiated keratinised cells and is shed with exfoliated cells of the stratum corneum.

Papillomaviruses are commonly found in normal skin of different animals, including the cat; 6 this makes definitive proof of a causal relationship between the presence of papillomavirus sequences and skin lesions difficult.

Clinical signs

In cats, papillomaviruses have been associated with different skin lesions.

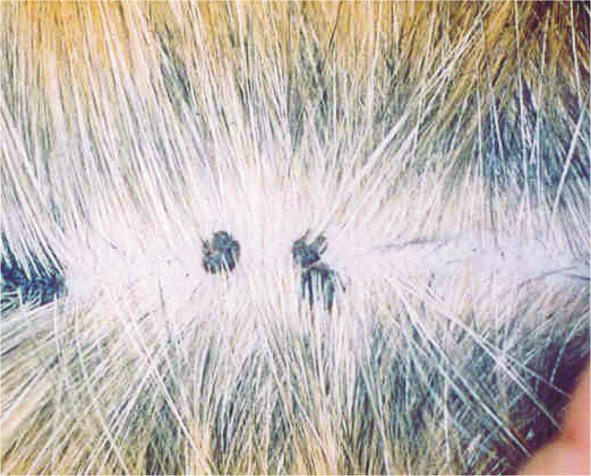

First, cutaneous hyperkeratotic plaques seem to be most common in older and immunosuppressed cats – eg, feline immunodeficiency virus-infected animals.7,8 However, plaques have also been reported in cats without any recognised immunodeficiency. 9 The plaques appear as flat, slightly raised scaly and variably pigmented lesions (Figure 1).

Second, viral plaques can progress into Bowenoid in situ carcinomas (BISCs), and further to invasive squamous cell carcinomas (ISCCs). Feline BISCs occur often in pigmented, haired skin and appear as crusting, hyperpigmented and roughly circular lesions. Sunlight plays a role in the development of ISCCs, with lesions tending to be found in sparsely haired areas such as eyelids, nose and pinnae. A clear association between papillomavirus DNA (the Felis domesticus papillomavirus 2 – FdPV-2) and squamous cell carcinoma has been found; it was detected in all 20 BISCs examined, and in 17/20 cases of ISCC. However, FdPV-2 DNA could also be detected in 52% of normal skin swabs. 6 In one study, 50% of the sequenced papillomavirus DNA was most closely related to human papillomavirus DNA. In a recent study, papillomavirus DNA could not be detected in any of 30 oral squamous cell carcinoma samples screened, 10 which is at variance with earlier observations.

Third, feline cutaneous fibropapillomas or feline sarcoids may be caused by papillomavirus infection. They are rare, occurring as skin neoplasms (nodular masses) found most commonly on the head, neck, ventral abdomen and limbs (Figure 2). The finding of a papillomavirus similar to bovine papillomavirus type 1, and the higher prevalence in cats with known exposure to cattle, suggest an association with the bovine virus.11,12 This hypothesis is in line with the known association between bovine papillomavirus and equine sarcoids.

Fourth, papillomaviruses have been associated with feline cutaneous papillomas. 13

Figure 1.

Pigmented flat cutaneous papillomas. Courtesy of Herman Egberink, PhD thesis, Utrecht

Figure 2.

A case of sarcoid in a patient presented at the Utrecht Companion Animal Clinic; diagnosis was verified histologically, but the viral etiology was not established. Courtesy of Y Schlotter, Companion Animal Clinic, Veterinary Faculty, Utrecht University

Diagnosis

A biopsy from a skin lesion can be taken for histopathological examination and immunohistochemical staining of papillomavirus group-specific antigens. By electron microscopy, intranuclear papillomavirus-like particles might be demonstrated in keratinised cells. Also PCR can be used to demonstrate papillomavirus DNA in the lesions and for identification of the viral strain by further sequencing. However, the presence of papillomavirus DNA in normal skin of cats makes interpretation of positive PCR results of skin lesions difficult [EBM grade I].

Disease management

No specific treatment is known. In immunocompetent cats, spontaneous regression can be expected, as is also seen in dogs, but it may take a long time, up to several months [EBM grade IV]. Imiquimod (Aldara), used for topical treatment of Bowen’s disease in humans, has never been thoroughly evaluated in cats with this condition; a response was noted but no conclusion with respect to the efficacy of the drug in cats can be drawn [EBM grade III]. 14 In this study the ISCC lesions were also papillomavirus antigen negative. Feline ISCCs tend to slowly metastasise. Therefore, if the anatomical location allows, complete excision might be curative.

There are no vaccines available for papillomatosis in cats.

Footnotes

Funding: The authors received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors for the preparation of this article. The ABCD is supported by Merial, but is a scientifically independent body.

The authors do not have any potential conflicts of interest to declare.

Key Points

Papillomavirus infections are associated with skin lesions but the virus can also be found in normal skin.

Besides cat-specific papillomaviruses, DNA sequences most closely related to human and bovine wart viruses have been detected in skin lesions.

The diagnosis is supported by the intralesional detection of viral antigen or DNA.

There is no specific treatment for papillomavirus-induced skin lesions.

References

- 1. Munday JS, Kiupel M. Papillomavirus-associated cutaneous neoplasia in mammals. Vet Pathol 2010; 47: 254–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Munday JS, Willis KA, Kiupel M, Hill FI, Dunowska M. Amplification of three different papillomaviral DNA sequences from a cat with viral plaques. Vet Dermatol 2008; 19: 400–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. O’Neill SH, Newkirk KM, Anis EA, Brahmbhatt R, Frank LA, Kania SA. Detection of human papillomavirus DNA in feline premalignant and invasive squamous cell carcinoma. Vet Dermatol 2011; 22: 68–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Anis EA, O’Neill SH, Newkirk KM, Brahmbhatt RA, Abd-Eldaim M, Frank LA, et al. Molecular characterization of the L1 gene of papillomaviruses in epithelial lesions of cats and comparative analysis with corresponding gene sequences of human and feline papillomaviruses. Am J Vet Res 2010; 71: 1457–1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sundberg JP, Van Ranst M, Montali R, Homer BL, Miller WH, Rowland PH, et al. Feline papillomas and papillomaviruses. Vet Pathol 2000; 37: 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Munday JS, Witham AI. Frequent detection of papillomavirus DNA in clinically normal skin of cats infected and non-infected with feline immunodeficiency virus. Vet Dermatol 2010; 21: 307–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Egberink HF, Berrocal A, Bax HA, van den Ingh TS, Walter JH, Horzinek MC. Papillomavirus associated skin lesions in a cat seropositive for feline immunodeficiency virus. Vet Microbiol 1992; 31: 117–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Carney HC, England JJ, Hodgin EC, Whiteley HE, Adkison DL, Sundberg JP. Papillomavirus infection of aged Persian cats. J Vet Diagn Invest 1990; 2: 294–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wilhelm S, Degorce-Rubiales F, Godson D, Favrot C. Clinical, histological and immunohistochemical study of feline viral plaques and bowenoid in situ carcinomas. Vet Dermatol 2006; 17: 424–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Munday JS, Knight CG, French AF. Evaluation of feline oral squamous cell carcinomas for p16CDKN2A protein immunoreactivity and the presence of papillomaviral DNA. Res Vet Sci 2011; 90: 280–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Schulman FY, Krafft AE, Janczewski T. Feline cutaneous fibropapillomas: clinicopathologic findings and association with papillomavirus infection. Vet Pathol 2001; 38: 291–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Munday JS, Knight CG, Howe L. The same papillomavirus is present in feline sarcoids from North America and New Zealand but not in any non-sarcoid feline samples. J Vet Diagn Invest 2010; 22: 97–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Munday JS, Kiupel M, French AF, Howe L, Squires RA. Detection of papillomaviral sequences in feline Bowenoid in situ carcinoma using consensus primers. Vet Dermatol 2007; 18: 241–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gill Vl, Bergman PJ, Baer KE, Craft D, Leung C. Use of imiquimod 5% cream (AldaraTM) in cats with multicentric squamous cell carcinoma in situ: 12 cases (2002–2005). Vet Comp Oncol 2008; 6: 55–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]