Abstract

Overview:

Tritrichomonas foetus is a protozoan organism that is specific to cats and can cause large bowel diarrhoea. It is distinct from other Tritrichomonas species and not considered to be zoonotic. Infection is most common in young cats from multicat households, particularly pedigree breeding catteries.

Disease signs:

Affected cats show frequent fetid diarrhoea, often with mucus, fresh blood and straining, but generally remain bright and do not lose weight.

Diagnosis:

Diagnosis of infection is usually based on direct microscopic examination of freshly voided faeces. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing is more sensitive but may detect infections unrelated to diarrhoea and, therefore, requires care in interpretation.

Treatment:

The treatment of choice is ronidazole, which should be used with care as it is an unlicensed drug for cats with a narrow safety margin. Clinical signs are generally self-limiting in untreated cases, but may take months to resolve.

Agent

Tritrichomonas foetus is a highly motile flagellate protozoan parasite (Figure 1) that resides in the large intestine of cats, where it causes a pathology.1–4 It is distinct from Pentatrichomonas hominis, which infects humans. 3 T foetus is also recognised as a parasite of the reproductive tract of cattle. However, Tritrichomonas isolated from cats does not cause the same pathology as bovine isolates in experimental infection of cattle, and vice versa. Furthermore, recent molecular studies have identified sequence differences between feline and bovine isolates, suggesting they are distinct strains.

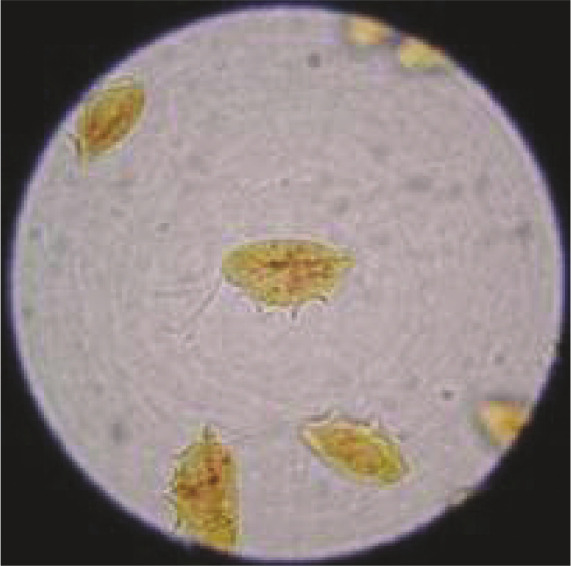

Figure 1.

T foetus stained with Lugol’s iodine. Three anterior flagellae can be seen, and an undulating membrane runs the length of the body. Courtesy of International Cat Care (formerly Feline Advisory Bureau)

Life cycle

During replication in the mucus of the large intestine, trophozoites are produced by binary fission and excreted in the faeces. No oocyst form exists for Tritrichomonas. Transmission occurs via the faecal–oral route. The trophozoites have very limited ability to survive outside the cat and do not persist in the environment.

Epidemiology

Prevalence studies have given variable results, depending on the test used, but the background of the cats is also an important variable. Surveys based on PCR testing give the highest prevalence, sometimes over 70%. This makes it difficult to show an association between infection and the symptom of diarrhoea; the test may detect infections not associated with the clinical picture. In other studies a figure of up to 30% has been found, but when comparing the prevalence in cats with clinical signs with that in healthy cats from the same background, there has not always been a clear difference. Infection is more common in cats from multicat environments, particularly from breeding colonies. Groups may be affected, but also single cats within the household. Infection is more common in young cats: 75% of cases are in cats less than 1 year of age.

Studies in Europe have concentrated on cats with chronic diarrhoea, and T foetus has indeed been detected in the faeces of up to 32% of cats in the UK, Italy, Switzerland and the Netherlands,5 –10 as well as in cats from Germany attending an international cat show in the USA. 11 More recently, the protozoan was found in 19% of cats with chronic diarrhoea sampled in Austria, 12 and in 15.7% of randomly sampled cats and 18.5% of cattery cats in Germany. 13

Pathogenesis

The mechanism by which Tritrichomonas induces diarrhoea is not clear. It resides in the mucus on the mucosal surface of the large intestine and adherence factors may be important. The organism may produce toxins and induces an inflammatory response in the colon.

Clinical signs

Not all infections are associated with clinical signs. The parasite targets the large bowel, and the features of the diarrhoea are usually suggestive of colitis, with frequent passage of small quantities of liquid to semi-formed faeces, often with blood, mucus and some straining. Some affected cats develop faecal incontinence. The parasite has been found in the genital tract of cats but does not appear to be linked to reproductive disease.

Immunity

Little is known about the immunity to Tritrichomonas. Infections generally resolve, which suggests that infected cats develop an effective immune response.

Diagnosis

The organism can be identified in fresh faeces by direct examination, which reveals the motile trophozoites. The flagellae induce a jerky motion that can aid in differentiation from the trophozoites of Giardia. If mucus is passed with the faeces, this represents a good sample for examination. Faeces are suspended in saline and examined under a cover slip at x200–400. Infection can also be diagnosed using PCR, which is becoming more widely available, and by culturing the organism, for which the ‘In Pouch’ culture system is used.

There are marked differences in the sensitivity of the different diagnostic tests. PCR may have the disadvantage of identifying infections that are not clinically relevant; detection of trophozoites in faecal smears, or culture of the organism, may be the best tests for identifying cases for which treatment is indicated. Trophozoites may be difficult to identify on histopathological examination of colonic biopsies.

Treatment

The drug of choice is ronidazole, a nitroimidazole related to metronidazole. It is not licensed for use in cats and experience is limited, although it appears to be effective [EBM grade III]. It can be obtained as a powder and formulated in capsules, or as a pigeon remedy. There has been recent debate about the appropriate dose – currently 30 mg/kg q24h is recommended [EBM grade III]. This is lower than some previous recommendations but reduces the risk of side effects (neurotoxicity, as with metronidazole). Initial experience indicated that metronidazole is not effective, but this finding needs to be reviewed. The diarrhoea will usually resolve spontaneously in untreated cats, although this may take months or longer [EBM grade IV].

A key unanswered question when infection is identified in a group of cats is which cats should be treated – all animals in the group or just cats with diarrhoea? A reasonable approach is to treat only cats that are showing signs and are positive on faecal smears.

Footnotes

Funding: The authors received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors for the preparation of this article. The ABCD is supported by Merial, but is a scientifically independent body.

The authors do not have any potential conflicts of interest to declare.

Key Points

Tritrichomonas foetus is a protozoan parasite of the large bowel.

It is specific to cats and not considered zoonotic.

Clinical disease is most common in young cats from multicat households, particularly pedigrees.

Infection causes large bowel diarrhoea with frequent passage of malodorous faeces, often with mucus and blood.

Tritrichomoniasis is diagnosed by direct examination of fresh faeces or PCR, but careful interpretation is important, as infection can be detected in healthy cats.

Ronidazole is the treatment of choice, but therapy requires care.

References

- 1. Gookin JL, Levy MG, Law JM, Papich MG, Poore MF, Breitschwerdt EB. Experimental infection of cats with Tritrichomonas foetus. Am J Vet Res 2001; 62: 1690–1697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gookin JL, Breitschwerdt EB, Levy MG, Gager RB, Benrud JG. Diarrhea associated with trichomonosis in cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1999; 215: 1450–1454. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Levy MG, Gookin JL, Poore M, Birkenheuer AJ, Dykstra MJ, Litaker RW. Tritrichomonas foetus and not Pentatrichomonas hominis is the etiologic agent of feline trichomonal diarrhea. J Parasitol 2003; 89: 99–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Levy MG, Gookin JL, Poore MF, Litaker RW, Dykstra M. Information on parasitic gastrointestinal tract infections in cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2001; 218: 194–195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gunn-Moore DA, McCann TM, Reed N, Simpson KE, Tennant B. Prevalence of Tritrichomonas foetus infection in cats with diarrhoea in the UK. J Feline Med Surg 2007; 9: 214–218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Burgener I, Frey C, Kook P, Gottstein B. Tritrichomonas fetus: a new intestinal parasite in Swiss cats. Schweiz Arch Tierheilkd 2009; 151: 383–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mardell EJ, Sparkes AH. Chronic diarrhoea associated with Tritrichomonas foetus infection in a British cat. Vet Rec 2006; 158: 765–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Holliday M, Deni D, Gunn-Moore DA. Tritrichomonas foetus infection in cats with diarrhoea in a rescue colony in Italy. J Feline Med Surg 2009; 11: 131–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Frey CF, Schild M, Hemphill A, Stünzi P, Müller N, Gottstein B, et al. Intestinal Tritrichomonas foetus infection in cats in Switzerland detected by in vitro cultivation and PCR. Parasitol Res 2009; 104: 783–788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. van Doorn DC, de Bruin MJ, Jorritsma RA, Ploeger HW, Schoormans A. Prevalence of Tritrichomonas foetus among Dutch cats. Tijdschr Diergeneeskd 2009; 134: 698–700. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gookin JL, Stebbins ME, Hunt E, Burlone K, Fulton M, Hochel R, et al. Prevalence of and risk factors for feline Tritrichomonas foetus and Giardia infection. J Clin Microbiol 2004; 42: 2707–2710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Steiner JM, Xenoulis PG, Read SA, et al. Identification of Tritrichomonas foetus DNA in feces from cats with diarrhea from Germany and Austria [abstract]. J Vet Intern Med 2009; 21: 649. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kuehner KA, Marks SL, Kass PH, Sauter-Louis C, Grahn RA, Barutzki D, et al. Tritrichomonas foetus infection in purebred cats in Germany: prevalence of clinical signs and the role of co-infection with other enteroparasites. J Feline Med Surg 2011; 13: 251–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]