Abstract

Overview:

Phaeohyphomycoses and hyalohyphomycoses are rare opportunistic infections acquired from the environment. More cases have been reported in recent years in humans and cats.

Disease signs:

Single or multiple nodules or ulcerated plaques (which may be pigmented) in the skin are the typical lesions. In some cases the infection disseminates or involves the central nervous system (CNS).

Diagnosis:

Diagnosis is based on fungal detection by cytology and/or histology. Culture provides definitive diagnosis and species identification.

Treatment:

Treatment involves surgical excision in cases of localised skin disease followed by systemic antifungal therapy, with itraconazole as the agent of first choice. Relapses after treatment are common. Itraconazole and other systemic antifungal agents have been used to treat systemic or neurological cases, but the response is unpredictable. The prognosis is guarded to poor in cats with multiple lesions and systemic or neurological involvement.

Zoonotic risk:

There is no zoonotic risk associated with contact with infected cats.

Fungal properties and epidemiology

Phaeohyphomycoses are rare opportunistic fungal infections caused by numerous genera of fungal moulds that characteristically produce melanin-pigmented ‘dematiaceous’ (dark-coloured) hyphal elements in tissues and in culture (Figures 1 and 2); yeast-like forms have also been found in some cases. 1 Hyalohyphomycoses are caused by several genera of fungi that are non-pigmented, being transparent or hyaline in tissues. 1

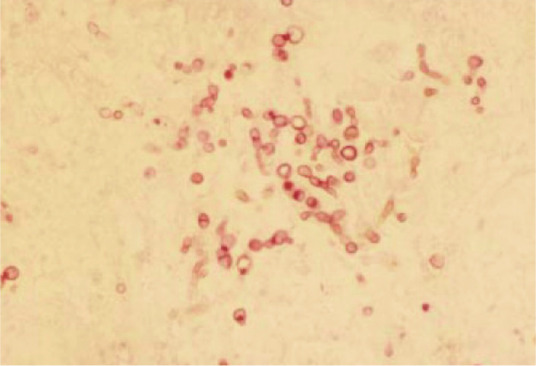

Figure 1.

Dark-coloured, periodic acid-Schiff-positive, fungal structures in a tissue sample. Courtesy of Alessandra Fondati

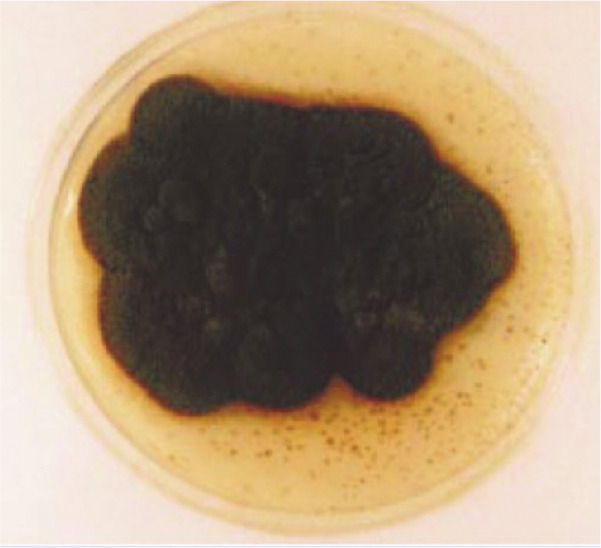

Figure 2.

‘Dematiaceous’ (dark-coloured) colony. Courtesy of Alessandra Fondati

Both are ubiquitous saprophytic agents. The number of reports of infections is increasing in humans and animals, often associated with immunosuppressive treatment or an immunosuppressive condition. In human medicine, they are currently considered emerging fungal infections.2,3

Infections are acquired from traumatic implantation from the environment (soil and decomposed plants). Direct transmission between hosts does not occur. 1

The taxonomy of the aetiological agents is complicated, and names have often been changed. More than 100 species classified within 60 genera have been described as agents of phaeohyphomycosis in animals and humans. Pathogens for dogs and cats include species from Alternaria, Bipolaris, Cladophialophora and Curvularia. Genera with species causing disease in cats, but not in dogs, are Exophiala, Fonsecaea, Macrophomina, Microsphaerosis, Moniliella, Phialophora, Phoma, Scolecobasidium and Stemphylium.

Genera with species causing hyalohyphomycosis in dogs and cats include Fusarium, Acremonium, Paecilomyces, Pseudallescheria, Sagemonella, Phialosimplex and Scedosporium.

Feline phaeohyphomycosis probably has a worldwide distribution as sporadic cases have been reported from North America, Spain, 4 Italy,5,6 Australia, 7 Canada, 8 the UK9,10 and Japan. 11

A retrospective study from the UK evaluating 77 cats with nodular granulomatous skin lesions caused by fungal infection found that the most frequent cause was hyalohyphomycosis. Phaeohyphomycosis and deep pseudomycetomas were less frequently diagnosed. 9

Pathogenesis

Infection occurs mainly through contact or skin puncture, especially through trauma involving wood. 1 Respiratory tract colonisation is suspected to occur in systemic cases. In the rare cases of CNS infection, the route of exposure has not been elucidated, but an extension from sinuses, the orbit and middle ear has been suggested.1,12 Local infections are rarely associated with systemic diseases or immunosuppression. 1 The infrequent cases of systemic disseminated infection may or may not be associated with immunosuppression.

Clinical presentation

Nodules or masses in the skin or nasal mucosa are the most common clinical problem. Ulcerated, crusting or fistulating nodules, non-ulcerated subcutaneous nodules and/or plaques, which can be focal or multifocal and locally invasive, are typical lesions.4–11 The lesions may appear pigmented, 1 but are otherwise not different from chronic bacterial infection or cystic skin lesions. In most cases they are found in the facial region, and on the distal part of the extremities or the tail. A typical presentation is a nodule on the bridge of the nose. 4 A case of a focal pulmonary granuloma caused by Cladophialophora bantiana has been reported in a cat. 13

A few cases in the literature concern fungal infections that were responsible for multifocal neurological signs due to encephalitis or brain abscesses 12 or for disseminated disease,14,15 especially in association with immunosuppression. In these cases the causative organism has been identified as Cladosporium species. Most cases have been diagnosed post mortem.

Diagnosis

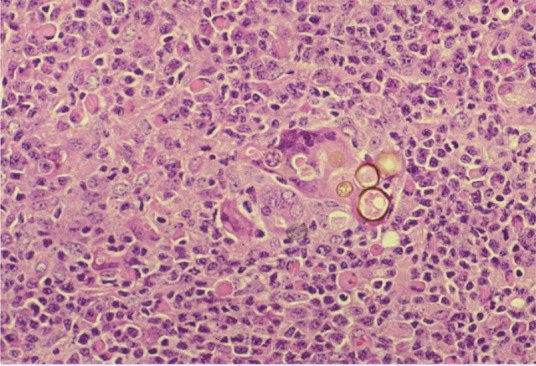

Diagnosis is based on visualisation of the fungal organism on cytology and/or histology, which usually shows a nodular to diffuse pyogranulomatous inflammation pattern. In tissue, the presence of pigmented fungal structures in the centre of the pyogranulomatous reaction is highly suggestive of phaeohyphomycosis (Figure 3).1,4–11 Special fungal stains such as Gomori methenamine silver or periodic acid-Schiff can enhance the diagnostic sensitivity.

Figure 3.

Pigmented fungal structures in a tissue sample. Courtesy of Lluís Ferrer

Definitive diagnosis relies on fungal culture and identification of the fungal species based on morphology and pigmentation features by specialised laboratories. 1

Molecular techniques have only seldom been used to identify pathogenic fungal species. 11

Treatment

No prospective studies exist on the treatment of feline phaeohyphomycosis or hyalohyphomycosis. Recommendations are based on case reports.

The approach for local lesions is aggressive surgical excision, as these rarely respond to antifungal treatment. After surgery of a single lesion, if multiple lesions exist or in cases of disseminated infection, itraconazole is the treatment of choice [EBM grade IV]. Disseminated or neurological cases are poorly responsive to treatment. Ketoconazole, amphotericin B and posaconazole have been used in a few cases [EBM grade IV].1,13

Table 1 lists the treatment options for these infections.

Table 1.

Treatment of phaeohyphomycosis and hyalohyphomycosis

| Drug/treatment | Dose and frequency | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Surgical excision | Radical surgery with wide margins | |

| Itraconazole | 10 mg/kg PO q24h | Consider if multiple lesions or post-surgery |

| Posaconazole | 5 mg/kg q24h PO | Consider in severe or disseminated disease |

| Amphotericin B | 0.25 mg/kg q48h IV to a total | Consider in severe or disseminated disease |

There are no vaccines available.

Footnotes

Funding: The authors received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors for the preparation of this article. The ABCD is supported by Merial, but is a scientifically independent body.

The authors do not have any potential conflicts of interest to declare.

Key Points

Sporadic cases of these fungal diseases have been reported in cats.

Skin nodules and ulcers, especially involving the facial area, distal extremities and tail, are the most frequent lesions.

Dissemination and CNS signs may occur in rare cases, especially with Cladosporium species infection.

Histology and culture are the most useful diagnostic tests. Some fungi show a typical pigmentation, which is helpful for diagnosis.

A combination of surgery and systemic antifungal treatment (itraconazole) may cure cases with localised lesions.

Cases of disseminated skin disease or systemic disease have a poor prognosis; new azole drugs like posaconazole should be considered in these cats.

References

- 1. Grooters AM, Foil CS. Miscellaneous fungal infections. In: Greene CE. (ed). Infectious diseases of the dog and the cat. 3rd ed. St Louis: Saunders Elsevier, 2006, pp 637–650. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Revankar SG, Patterson JE, Sutton DA, Pullen R, Rinaldi MG. Disseminated phaeohyphomycosis: review of an emerging mycosis. Clin Infect Dis 2002; 34: 467–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fothergill AW. Identification of dematiaceous fungi and their role in human disease. Clin Infect Dis 1996; 22: S179–S184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fondati A, Gallo MG, Romano E, Fondevila D. A case of feline phaeohyphomycosis due to Fonsecaea pedrosoi. Vet Dermatol 2001; 2: 297–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Beccati M, Vercelli A, Peano A, Gallo MG. Phaeohyphomycosis by Phialophora verrucosa: first European case in a cat. Vet Rec 2005; 157: 93–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Abramo F, Bastelli F, Nardoni S, Mancianti F. Feline cutaneous phaeohyphomycosis due to Cladophyalophora bantiana. J Feline Med Surg 2002; 4: 157–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kettlewell P, McGinnis MR, Wilkinson GT. Phaeohyphomycosis caused by Exophiala spinifera in two cats. J Med Vet Mycol 1989; 27: 257–264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Outerbridge CA, Myers SL, Summerbell RC. Phaeohyphomycosis in a cat. Can Vet J 1995; 36: 629–630. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Miller RI. Nodular granulomatous fungal skin disease of cats in the United Kingdom: a retrospective review. Vet Dermatol 2010; 21: 130–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Knights CB, Lee K, Rycroft AN, Patterson-Kane JC, Baines SJ. Phaeohyphomycosis caused by Ulocladium species in a cat. Vet Rec 2008; 162: 415–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Maeda H, Shibuya H, Yamaguchi Y, Miyoshi T, Irie M, Sato T. Feline digital phaeohyphomycosis due to Exophiala jeanselmei. J Vet Med Sci 2008; 70: 1395–1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bouljihad M, Lindeman CJ, Hayden DW. Pyogranulomatous meningoencephalitis associated with dematiaceous fungal (Cladophialophora bantiana) infection in a domestic cat. J Vet Diagn Invest 2002; 14: 70–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Evans N, Gunew M, Marshall R, Martin P, Barrs V. Focal pulmonary granuloma caused by Cladophialophora bantiana in a domestic shorthair cat. Med Mycol 2011; 49: 194–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Elies L, Balandraud V, Boulouha L, Crespeau F, Guillot J. Fatal systemic phaeohyphomycosis in a cat due to Cladophialophora bantiana. J Vet Med A Physiol Pathol Clin Med 2003; 50: 50–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mariani CL, Platt SR, Scase TJ, Howerth EW, Chrisman CL, Clemmons RM. Cerebral phaeohyphomycosis caused by Cladosporium spp. in two domestic shorthair cats. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2002; 38: 225–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]