Abstract

Overview:

Over 22 Bartonella species have been described in mammals, and Bartonella henselae is most common worldwide. Cats are the main reservoir for this bacterium. B henselae is the causative agent of cat scratch disease in man, a self-limiting regional lymphadenopathy, but also of other potentially fatal disorders in immunocompromised people.

Infection:

B henselae is naturally transmitted among cats by the flea Ctenocephalides felis felis, or by flea faeces. A cat scratch is the common mode of transmission of the organism to other animals, including humans. Blood transfusion also represents a risk.

Disease signs:

Most cats naturally infected by B henselae do not show clinical signs but cardiac (endocarditis, myocarditis) or ocular (uveitis) signs may be found in sporadic cases. B vinsonii subspecies berkhoffii infection has reportedly caused lameness in a cat affected by recurrent osteomyelitis and polyarthritis.

Diagnosis:

Isolation of the bacterium is the gold standard, but because of the high prevalence of infection in healthy cats in endemic areas, a positive culture (or polymerase chain reaction) is not confirmatory. Other compatible diagnoses must be ruled out and response to therapy gives a definitive diagnosis. Serology (IFAT or ELISA) is more useful for exclusion of the infection because of the low positive predictive value (39–46%) compared with the good negative predictive value (87–97%). Laboratory testing is required for blood donors.

Disease management:

Treatment is recommended in the rare cases where Bartonella actually causes disease.

Bacterial properties

Bartonella (previously named Rochalimaea) species are small, vector-transmitted Gram-negative intracellular bacteria that are well adapted to one or more mammalian reservoir hosts.

To date, over 22 Bartonella species have been described, but their role as pathogens of humans and domestic animals is the subject of ongoing investigations (Table 1). 1 The most common species in both cats and humans is B henselae, the agent of cat scratch disease as well as of other potentially fatal disorders in immunocompromised people.

Table 1.

Species and subspecies of Bartonella that are confirmed or potential human pathogens 1

| Bartonella species | Primary reservoir | Vector | Accidental host |

|---|---|---|---|

| B bacilliformis | Human | Lutzomyia verrucarum | None |

| B quintana * | Human | Pediculus humanus | Cat, dog, monkey |

| B elizabethae | Rattus norvegicus | Xenopsylla cheopis | Human, dog |

| B grahamii | Several species of wild mice | Rodent fleas | Human |

| B henselae * | Cat | Ctenocephalides felis felis (C felis) Other vectors? | Human, dog |

| B clarridgeiae * | Cat | C felis | Human, dog |

| B koehlerae * | Cat | C felis | Human |

| B vinsonii subspecies berkhoffii * | Coyote, dog | Ticks? | Human, cat |

| B vinsonii subspecies arupensis | Peromyscus leucopus | Ticks? Fleas? | Human |

| B washoensis | Spermophilus beecheyii | Fleas? | Human, dog |

| B asiatica | Rabbit | Fleas? | Human |

*Zoonotic species

B henselae is naturally transmitted among cats by the flea Ctenocephalides felis felis, or by flea faeces. In the infected cat, Bartonella inhabits red blood cells, which are ingested by the flea, and the bacterium survives in the flea’s gut. Contaminated flea faeces deposited on the skin of the cat end up under the cat’s claws due to self-scratching. A cat scratch is the common mode of transmission of the organism to other animals, including humans. 2

B henselae has been experimentally transmitted among cats by transferring fleas fed on naturally infected cats to specific pathogen-free (SPF) cats, and by intradermal inoculation of excrement collected from fleas fed on B henselae-infected cats. 2 This has demonstrated that both the vector and the cat – through scratches – may transmit the organism. Infection is amplified in the flea hindgut, and B henselae can persist in the environment in flea faeces for at least 9 days. 3 Blood transfusion also represents a risk: cats have been experimentally infected with B henselae and B clarridgeiae by intravenous or intramuscular inoculation with infected cat blood. 4

B henselae transmission did not occur when infected cats lived together with uninfected cats in a flea-free environment. Transmission consequently does not occur through bites, scratches (in the absence of fleas), grooming, or sharing of litter boxes and food dishes. Furthermore, transmission could not be demonstrated between bacteraemic female cats and uninfected males during mating, or to the kittens of infected females either during gestation or in the neonatal period, again in flea-free environments. 5

Ticks may also act as vectors for transmission among cats, human beings, dogs and other mammalian hosts: trans-stadial transmission of B henselae was demonstrated in Ixodes ricinus. 6

Epidemiological evidence and experimental studies have demonstrated the important role of fleas in the transmission of B henselae and B clarridgeiae among cats. Three other species, B koehlerae, B bovis and B quintana, have been isolated from cat blood, but the modes of transmission and the reservoir potential of these species in felids have not been established. In addition, B vinsonii subspecies berkhoffii DNA was detected in the blood of a cat. 7

Epidemiology

Bartonella species have a worldwide distribution, with highest prevalences in areas where conditions are most favourable for arthropod vectors, mainly fleas. In Europe, many studies have been carried out and the antibody prevalence in cats has ranged from 8–53% (Table 2).

Table 2.

Antibody prevalence of Bartonella infection in the feline population in European countries

| Country | Number of cats | Prevalence (%) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Netherlands | 163 (stray) | 52 | Bergmans et al (1997) 8 |

| Austria | 96 | 33 | Allerberger et al (1995) 9 |

| Switzerland | 728 | 8 | Glaus et al (1997) 10 |

| Germany | 713 | 15 | Haimerl et al (1999) 11 |

| 245 | 37.1 | Morgenthal et al (2012) 12 | |

| France | 64 | 36 | Chomel et al (1995) 13 |

| 94 | 53 | Heller et al (1997) 14 | |

| 179 | 41 | Gurfield et al (2001) 15 | |

| Spain | 680 | 23.8 | Ayllon et al (2012) 16 |

| Italy | 540 | 38 | Fabbi et al (2004) 17 |

| 1300 (stray) | 23.1 | Brunetti et al (2013) 18 | |

| Scotland | 78 | 15.3 | Bennett et al (2011) 19 |

Pathogenesis

Chronic bacteraemia mainly occurs in young cats, under the age of 2 years. 20 Young experimentally infected cats maintained relapsing B henselae or B clarridgeiae bacteraemia for as long as 454 days. 21 Immune system avoidance via intracellular location, frequent genetic rearrangements and alteration of outer membrane proteins are considered important factors for the maintenance of persistent bacteraemia. The location within erythrocytes and vascular endothelial cells is believed to protect Bartonella also from antimicrobial agents.

As the host-adapted reservoir of B henselae, cats display minimal pathogenic effects after experimental infection. Gross necropsy findings were unremarkable in experimentally infected cats but some histopathological changes emerged: follicular hyperplasia of lymph nodes and spleen, lymphocyte and plasma cell infiltrates in liver, heart, kidney and eye, and pyogranulomatous inflammation in liver, spleen, kidney, heart and lymph nodes.5,21

Immunity

The antibody response to B henselae has been investigated for the identification of vaccine candidates. The kinetics in response to B henselae antigens in chronically infected experimental cats is highly variable in degree and duration.2,21,22 Reinfection by a different strain of B henselae is possible, as supported by the isolation of unrelated bacterial clones from the same cat at different times. 23 Antibodies are, therefore, considered not protective, and Bartonella species antibody positive cats may be infected. 17 A cell-mediated response was not evident in investigated experimentally infected cats. 21

Clinical signs

Cats naturally infected with Bartonella species usually do not show clinical signs. Both experimental and natural infection studies have tried to establish an association between clinical signs and infection, but a link has not been unequivocally proven.

Experimental Infection

Exposure to infected fleas does not result in clinical signs [EBM grade II].2,24 In some cases of experimental inoculation, a self-limiting febrile disease, transient mild anaemia, localised or generalised lymphadenopathy, mild neurological signs and reproductive failure have been reported [EBM grade III]. 21

Natural Infection

The role of Bartonella as a cause of clinical signs is even more unclear after natural infection despite a plethora of studies. Studies based on antibody detection are of limited value because antibody only proves exposure, and not necessarily an active infection. Moreover, there is cross-reactivity between different Bartonella species and strains that may or may not cause clinical signs. Because of the high percentage of infected healthy cats in endemic areas an association between clinical signs and B henselae infection is not easy to demonstrate.

It has been suggested that Bartonella infection could play a role in chronic gingivostomatitis, but the prevalence of antibodies or organisms was not higher in diseased cats than in control populations [EBM grade II].10,25 –30

Cats positive for both feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV) and Bartonella antibodies had in one study an increased risk of lymphadenopathy [EBM grade III]. 25

An association between Bartonella antibodies and urinary tract disease or haematuria was found in two studies [EBM grade III].10,31

Pearce et al did not find any difference in antibody prevalence between healthy cats and cats with seizures or other neurological conditions. 32 A non-controlled retrospective study reported Bartonella DNA and antibodies in cerebrospinal fluid from cats with CNS disease [EBM grade III]. 33

No difference in Bartonella antibody prevalence was found between healthy cats and those affected by uveitis, but in some cases evidence of Bartonella species exposure was reported in cats with uveitis responsive to drugs considered effective against Bartonella [EBM grade IV].34–36

No difference in Bartonella antibody prevalence was found in cats affected by anaemia, but in cats positive for Bartonella antibodies a significant association with hyperglobulinaemia was seen [EBM grade I].37,38 Lappin et al demonstrated no association between fever and positivity to Bartonella antibodies or DNA. 39

A study based on serology and culture did not find an association between Bartonella infection and chronic rhinosinusitis. 40 Also no link was reported between Bartonella infection and pancreatitis, based on the finding that cats with normal feline pancreatic lipase immunoreactivity values and cats with elevated values did not show any difference in Bartonella antibody prevalence. 41

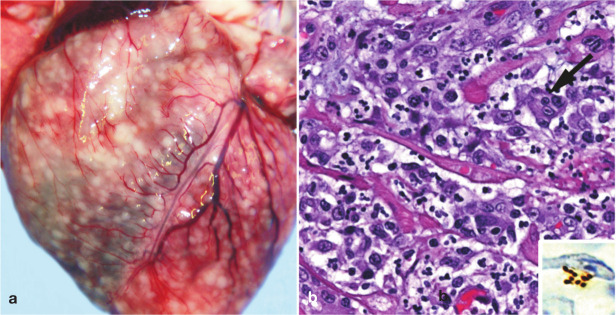

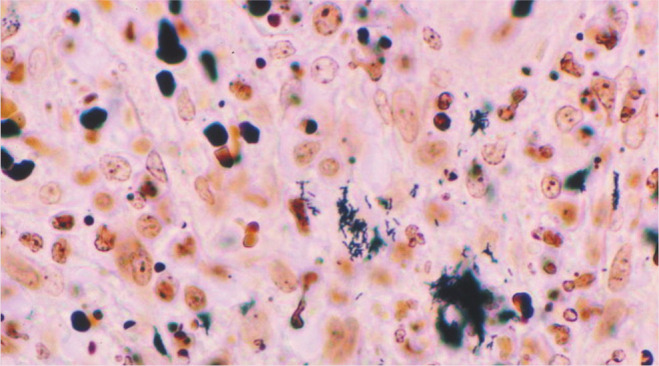

A few case reports concern B henselae-associated endocarditis or myocarditis. Fatal aortic and mitral valve B henselae-associated endocarditis was reported in two cats in the USA.42,43 Moreover, B henselae anterior mitral valve leaflet vegetative endocarditis was successfully treated in a cat presenting with a grade III/IV systolic heart murmur and signs of aortic embolisation (lethargy and weakness in the hind limbs, weak femoral pulses, pelvic pain, increased serum creatine kinase activity). 44 This case report confirms that Bartonella species may be a cause of blood culture-negative endocarditis, as suspected. 45 Bartonella-associated myocarditis was suspected in a cat presenting with supraventricular tachycardia responsive to antibiotic therapy. 46 Post mortem evidence of pyogranulomatous myocarditis and diaphragmatic myositis associated with B henselae infection was also obtained in two cats (Figure 1). 47

Figure 1.

Gross and histological findings in two cats from a North Carolina shelter that died after a litter of flea-infested kittens was introduced to the shelter. (a) Coalescing granulomas distributed throughout the myocardium of an approximately 9-week-old female kitten. (b) Pyogranulomatous myocarditis in an 8-month-old castrated male cat, which had been co-housed with the flea-infested kittens. Macrophages, with a rare multinucleated giant cell (arrow), are particularly numerous towards the upper left of the image; haematoxylin and eosin stain. Inset: Cluster of short bacilli in an inflammatory focus are immunoreactive (brown) for B henselae-specific monoclonal antibody; immunohistochemistry with diaminobenzidine chromogen and haematoxylin counterstain. Reproduced, with permission, from Varanat et al (2012) 47

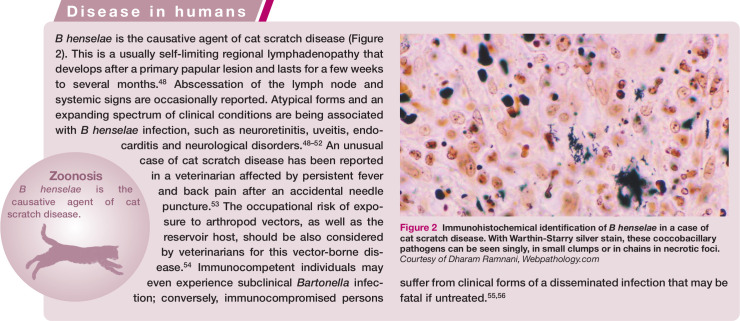

Figure 2.

Immunohistochemical identification of B henselae in a case of cat scratch disease. With Warthin-Starry silver stain, these coccobacillary pathogens can be seen singly, in small clumps or in chains in necrotic foci. Courtesy of Dharam Ramnani, Webpathology.com

Lameness and pain during limb palpation were observed in a cat affected by recurrent osteomyelitis and polyarthritis associated with B vinsonii subspecies berkhoffii infection and bacteraemia. 7

In conclusion, most cats naturally infected by B henselae do not show clinical signs. The identification of Bartonella infection in cats with disease should prompt a critical assessment of the role of the infection in the causation of the clinical signs and the exclusion of other compatible diagnoses.

Diagnosis

Bartonella laboratory testing is required for feline blood donors, for pet cats belonging to immunosuppressed persons, or when a human Bartonella-related disease is diagnosed in a cat’s home.

Isolation of the bacterium is the gold standard, but because of the high prevalence of infection in healthy cats in endemic areas, a positive culture is not confirmatory, and other compatible diagnoses must be ruled out.

The disease is, therefore, diagnosed on the basis of exclusion, and by assessing the response to therapy. The ex juvantibus inference about disease causation from the observed response to a treatment may apply to uveitis, endocarditis, myocarditis, osteoarthritis and multifocal central nervous system (CNS) disease, which are considered compatible with feline bartonellosis.

PCR may be used on samples of blood, aqueous humour, cerebrospinal fluid or tissues, and several gene targets have been studied. To reduce false-negative test results, repeated blood cultures are required or PCR performed on more than one kind of biological sample (blood, lymph node, oral swab).

Serology (IFAT or ELISA) is more useful for exclusion than for confirmation of the infection because of the low positive predictive value (39–46%) compared with the good negative predictive value (87–97%) [EBM grade III].13,15,17,20 Bartonella IgM antibodies are found in experimentally and naturally infected cats but their occurrence seems not to be related to bacteraemia [EBM grade II]. 57

Treatment

Treatment is recommended in the rare cases where Bartonella has actually caused disease (eg, endocarditis).

Current therapeutic strategies in cats (Table 3) are based on in vitro studies and human bartonellosis. Data from controlled efficacy studies in cats are lacking. A cat affected by recurrent osteomyelitis and polyarthritis associated with B vinsonii subspecies berkhoffii genotype II infection and bacteraemia recovered after therapy with azithromycin (10 mg/kg PO q48h for 3 months) and amoxicillin–clavulanate (62.5 mg PO q12 for 2 months) [EBM grade IV]. 7

Table 3.

Suggested treatment for bartonellosis in cats

| Drug | Dose | Duration | Reference(s) | EBM grade |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Doxycycline | 10 mg/kg PO q12–24 h | 2–4 weeks | Lappin and Black (1999) 35 | IV |

| Azithromycin | 10 mg/kg PO q24h (q48h) | For 7 days followed by every other day for 6–12 weeks | Ketring et al (2004)

36

Varanat et al (2009) 7 |

IV |

| Marbofloxacin | 5 mg/kg PO q24h | 6 weeks | Perez et al (2010) 44 | IV |

| Amoxicillin– clavulanate (with azithromycin) | 62.5 mg PO q12h | 2 months | Varanat et al (2009) 7 | IV |

After natural or experimental infection with B henselae or B clarridgeiae, healthy cats have been treated to eliminate bacteraemia and many drugs have been evaluated: doxycycline, amoxicillin, amoxicillin-clavulanate, enrofloxacin, erythromycin and rifampicin [EBM grade II].58–60 Based on these results, clearance of bacteraemia cannot be guaranteed and, in the case of failure, there is the risk of inducing antimicrobial resistance. Treatment of healthy carriers, therefore, cannot be considered an effective measure for eliminating the zoonotic risk, as is sometimes requested in human cases of cat scratch disease or where other Bartonella-related disease occurs in a family member.

Prevention

Based on transmission studies to date, strict flea (and tick) control is the only successful preventive measure. There is no vaccine available against Bartonella infection.

Footnotes

Funding: The authors received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors for the preparation of this article. The ABCD is supported by Merial, but is a scientifically independent body.

The authors do not have any potential conflicts of interest to declare.

Key Points

B henselae is the most common Bartonella species infecting cats, which are the main reservoir for this bacterium.

B henselae is the causative agent of cat scratch disease in man, a self-limiting regional lymphadenopathy.

B henselae is naturally transmitted among cats by the faeces of Ctenocephalides felis felis fleas; contact infections do not occur. Blood transfusion also represents a risk.

Most cats naturally infected by B henselae do not show clinical signs but sporadic cases of endocardial, myocardial or ocular feline disease have been reported.

Other Bartonella species, for which cats are accidental hosts, may have more pathogenic potential.

Antibodies are not protective, and seropositive cats may be reinfected.

Bartonellosis is diagnosed on the basis of exclusion, and by assessing the response to antibiotic therapy.

Testing healthy cats or people is of no benefit.

Treatment of healthy carriers is no measure for eliminating the zoonotic risk.

Strict flea and tick control is the only effective preventive measure.

References

- 1. Chomel BB, Boulouis H-J, Maruyama S, Breitschwerdt EB. Bartonella spp. in pets and effect on human health. Emerg Infect Dis 2006; 12: 389–394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chomel BB, Kasten RW, Floyd-Hawkins KA, Chi B, Yamamoto K, Roberts-Wilson J, et al. Experimental transmission of Bartonella henselae by the cat flea. J Clin Microbiol 1996; 34: 1952–1956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Finkelstein JL, Brown TP, O’Reilly KL, Wedincamp J, Jr, Foil LD. Studies on the growth of Bartonella henselae in the cat flea (Siphonaptera: Pulicidae). J Med Entomol 2002; 39: 915–919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Abbott RC, Chomel BB, Kasten RW, Floyd-Hawkins KA, Kikuchi Y, Koehler JE, et al. Experimental and natural infection with Bartonella henselae in cats. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis 1997; 20: 41–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Guptill L, Slater L, Wu C-C, Lin T-L, Glickman LT, Welch DF, et al. Experimental infection of young specific pathogen-free cats with Bartonella henselae. J Infect Dis 1997; 176: 206–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cottè V, Bonnet S, Le Rhun D, Le Naour E, Chauvin A, Boulouis H-J, et al. Transmission of Bartonella henselae by Ixodes ricinus. Emerg Infect Dis 2008; 14: 1074–1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Varanat A, Travis A, Lee W, Maggi RG, Bissett SA, Linder KE, et al. Recurrent osteomyelitis in a cat due to infection with Bartonella vinsonii subsp. berkhoffii genotype II. J Vet Intern Med 2009; 23: 1273–1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bergmans AMC, de Jong CMA, van Amerongen G, Schot CS, Schouls LM. Prevalence of Bartonella species in domestic cats in The Netherlands. J Clin Microbiol 1997; 35: 2256–2261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Allerberger F, Schonbauer M, Zangerle R, Dierich M. Prevalence of antibody to Rochalimaea henselae among Austrian cats. Eur J Ped 1995; 154: 165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Glaus T, Hofmann-Lehmann R, Greene C, Glaus B, Wolfensberger C, Lutz H. Seroprevalence of Bartonella henselae infection and correlation with disease status in cats in Switzerland. J Clin Microbiol 1997; 35: 2883–2885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Haimerl M, Tenter AM, Simon K, Rommel M, Hilger J, Autenrieth IB. Seroprevalence of Bartonella henselae in cats in Germany. J Med Microbiol 1999; 48: 849–856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Morgenthal D, Hamel D, Arndt G, Silaghi C, Pfister K, Kempf VA, et al. Prevalence of haemotropic Mycoplasma spp, Bartonella spp and Anaplasma phagocytophilum in cats in Berlin/Branderburg (Northeast Germany). Berl Munch Tierarztl Wochenschr 2012; 125: 418–427. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chomel BB, Gurfield AN, Boulouis HJ, Kasten RW, Piemont Y. Réservoir félin de l’agent de la maladie des griffes du chat, Bartonella henselae, en région parisienne: resultants préliminaires. Rec Med Vet 1995; 171: 841–845. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Heller R, Artois M, Xemar V, de Briel D, Gehin H, Jaulhac B, et al. Prevalence of Bartonella henselae and Bartonella clarridgeiae in stray cats. J Clin Microbiol 1997; 35: 1327–1331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gurfield AN, Boulouis H-J, Chomel BB, Kasten RW, Heller R, Bouillin C, et al. Epidemiology of Bartonella infection in domestic cats in France. Vet Microbiol 2001; 80: 185–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ayllon T, Diniz PP, Breitschwerdt EB, Villaescusa A, Rodriguez-Franco F, Sainz A. Vector-borne diseases in client-owned and stray cats from Madrid, Spain. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 2012; 12: 143–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fabbi M, De Giuli L, Tranquillo M, Bragoni R, Casiraghi M, Genchi C. Prevalence of Bartonella henselae in Italian stray cats: evaluation of serology to assess the risk of transmission of Bartonella to humans. J Clin Microbiol 2004; 42: 264–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Brunetti E, Fabbi M, Ferraioli G, Prati P, Filice C, Sassera D, et al. Cat-scratch disease in Northern Italy: atypical clinical manifestations in humans and prevalence of Bartonella infection in cats. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2013; 32: 531–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bennett AD, Gunn-Moore DA, Brewer M, Lappin MR. Prevalence of Bartonella species, haemoplasmas and Toxoplasma gondii in cats in Scotland. J Feline Med Surg 2011; 13: 553–557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Guptill L, Wu CC, HogenEsch H, Slater LN, Glickman N, Dunham A, et al. Prevalence, risk factors, and genetic diversity of Bartonella henselae infections in pet cats in four regions of the United States. J Clin Microbiol 2004; 42: 652–659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kordick D, Brown TT, Shin K, Breitschwerdt EB. Clinical and pathologic evaluation of chronic Bartonella henselae or Bartonella clarridgeiae infection in cats. J Clin Microbiol 1999; 37: 1536–1547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Yamamoto K, Chomel BB, Kasten RW, Hew CM, Weber DK, Lee WI. Experimental infection of specific pathogen free (SPF) cats with two different strains of Bartonella henselae type I: a comparative study. Vet Res 2002; 33: 669–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Arvand M, Viezens J, Berghoff J. Prolonged Bartonella henselae bacteremia caused by reinfection in cats. Emerg Infect Dis 2008; 14: 152–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bradbury CA, Lappin MR. Evaluation of topical application of 10% imidacloprid-1% moxidectin to prevent Bartonella henselae transmission from cat fleas. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2009; 236: 869–873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ueno H, Hohdatsu T, Muramatsu Y, Koyama H, Morita C. Does coinfection of Bartonella henselae and FIV induce clinical disorders in cats? Microbiol Immunol 1996; 40: 617–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Quimby J, Elston T, Hawley J, Brewer M, Miller A, Lappin MR. Evaluation of the association of Bartonella species, feline herpesvirus 1, feline calicivirus, feline leukemia virus and feline immunodeficiency virus with chronic feline gingivostomatitis. J Feline Med Surg 2008; 10: 66–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dowers KL, Hawley JR, Brewer MM, Morris AK, Radecki SV, Lappin MR. Association of Bartonella species, feline calicivirus, and feline herpesvirus 1 infection with gingivostomatitis in cats. J Feline Med Surg 2010; 12: 314–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pennisi MG, La Camera E, Giacobbe L, Orlandella BM, Lentini V, Zummo S, et al. Molecular detection of Bartonella henselae and Bartonella clarridgeiae in clinical samples of pet cats from Southern Italy. Res Vet Sci 2010; 88: 379–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Belgard S, Truyen U, Thibault JC, Sauter-Louis C, Hartmann K. Relevance of feline calicivirus, feline immunodeficiency virus, feline leukemia virus, feline herpesvirus and Bartonella henselae in cats with chronic gingivostomatitis. Berl Munch Tierarztl Wochenschr 2010; 123: 369–376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Namekata DY, Kasten RW, Boman DA, Straub MH, Siperstein-Cook L, Couvelaire K, et al. Oral shedding of Bartonella in cats: correlation with bacteremia and seropositivity. Vet Microbiol 2010; 146: 371–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Breitschwerdt EB, Levine JF, Radulovich S, Hanby SB, Kordick DL, La Perle KMD. Bartonella henselae and Rickettisa seroreactivity in a sick cat population from North Carolina. Int J Appl Res Vet Med 2005; 3: 287–302. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pearce LK, Radecki SV, Brewer M, Lappin MR. Prevalence of Bartonella henselae antibodies in serum of cats with and without clinical signs of central nervous system disease. J Feline Med Surg 2006; 8: 315–320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Leibovitz K, Pearce L, Brewer M, Lappin MR. Bartonella species antibodies and DNA in cerebral spinal fluid of cats with central nervous system disease. J Feline Med Surg 2008; 10: 332–337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Fontenelle JP, Powell CC, Hill AE, Radecki SV. Prevalence of serum antibodies against Bartonella species in the serum of cats with or without uveitis. J Feline Med Surg 2008; 10: 41–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lappin MR, Black JC. Bartonella spp infection as a possible cause of uveitis in a cat. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1999; 214: 1205–1207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ketring KL, Zuckerman EE, Hardy WD, Jr. Bartonella: a new etiological agent of feline ocular disease. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2004; 40: 6–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ishak AM, Radecki S, Lappin MR. Prevalence of Mycoplasma haemofelis, ‘Candidatus Mycoplasma haemominutum’, Bartonella species, Ehrlichia species, and Anaplasma phagocytophilum DNA in the blood of cats with anemia. J Feline Med Surg 2007; 9: 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Whittemore JC, Hawley JR, Radecki SV, Steinberg JD, Lappin MR. Bartonella species antibodies and hyperglobulinemia in privately owned cats. J Vet Intern Med 2012; 26: 639–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lappin MR, Breitschwerdt E, Brewer M, Hawley J, Hegarty B. Prevalence of Bartonella species antibodies and Bartonella species DNA in the blood of cats with and without fever. J Feline Med Surg 2009; 11, 141–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Berryessa NA, Johnson LR, Kasten RW, Chomel BB. Microbial culture of blood samples and serologic testing for bartonellosis in cats with chronic rhinosinusitis. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2008; 233: 1084–1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bayliss DB, Steiner JM, Sucholdolski JS, Radecki SV, Brewer MM, Morris AK, et al. Serum feline pancreatic lipase immunoreactivity concentration and seroprevalences of antibodies against Toxoplasma gondii and Bartonella species in client-owned cats. J Feline Med Surg 2009; 11: 663–667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Chomel B, Wey AC, Kasten RW, Stacy BA, Labelle P. Fatal case of endocarditis associated with Bartonella henselae type I infection in a domestic cat. J Clin Microbiol 2003; 41: 5337–5339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Chomel BB, Kasten RW, Williams C, Wey AC, Henn JB, Maggi R, et al. Bartonella endocarditis: a pathology shared by animal reservoirs and patients. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2009; 1166: 120–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Perez C, Hummel JB, Keene BW, Maggi RG, Diniz PPVP, Breitschwerdt EB. Successful treatment of Bartonella henselae endocarditis in a cat. J Feline Med Surg 2010; 12: 483–486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Malik R, Barrs VR, Church DB, Zahn A, Allan GS, Martin P, et al. Vegetative endocarditis in six cats. J Feline Med Surg 1999; 1: 171–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Nakamura RK, Zimmerman SA, Lesser MB. Suspected Bartonella-associated myocarditis and supraventricular tachycardia in a cat. J Vet Cardiol 2011; 13: 277–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Varanat M, Broadhurst J, Linder KE, Maggi RG, Breitschwerdt EB. Identification of Bartonella henselae in two cats with pyogranulomatous myocarditis and diaphragmatic myositis. Vet Pathol 2012; 49: 608–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Boulouis HJ, Chang CC, Henn JB, Kasten RW, Chomel BB. Factors associated with the rapid emergence of zoonotic Bartonella infections. Vet Res 2005; 36: 383–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Fonollosa A, Galdos M, Artaraz J, Perez-Irezabal J, Martinez-Alday N. Occlusive vasculitis and optic disk neovascularization associated with neuroretinitis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm 2011; 19: 62–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Tsuneoka H, Yanagihara M, Otani S, Katayama Y, Fujinami H, Nagafuji H, et al. A first Japanese case of Bartonella henselae-induced endocarditis diagnosed by prolonged culture of a specimen from the excised valve. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2010; 68: 174–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Mascarelli PE, Maggi RG, Hopkins S, Mozayeni BR, Trull CL, Bradley JM, et al. Bartonella henselae infection in a family experiencing neurological and neurocognitive abnormalities after woodlouse hunter spider bites. Parasit Vectors 2013; 6: 98. DOI: 10.1186/1756-3305-6-98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Maggi RG, Ericson M, Mascarelli PE, Bradley JM, Breitschwerdt EB. Bartonella henselae bacteremia in a mother and son potentially associated with tick exposure. Parasit Vectors 2013. 6: 101. DOI: 10.1186/1756-3305-6-101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Lin JW, Chen CM, Chang CC. Unknown fever and back pain caused by Bartonella henselae in a veterinarian after a needle puncture: a case report and literature review. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 2011; 11: 589–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Maggi RM, Mascarelli PE, Havenga LN, Naidoo V, Breitschwerdt EB. Co-infection with Anaplasma platys, Bartonella henselae and Candidatus Mycoplasma haematoparvum in a veterinarian. Parasit Vectors 2013; 6: 103. DOI: 10.1186/1756-3305-6-103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Massei F, Messina F, Gori L, Macchia P, Maggiore G. High prevalence of antibodies to Bartonella henselae among Italian children without evidence of cat scratch disease. Clin Infect Dis 2004; 38: 145–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Lange D, Oeder C, Waltermann K, Mueller A, Oehme A, Rohrberg R, et al. Bacillary angiomatosis. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2009; 7: 767–769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Ficociello J, Bradbury C, Morris A, Lappin MR. Detection of Bartonella henselae IgM in serum of experimentally infected and naturally exposed cats. J Vet Intern Med 2011; 25: 1264–1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Greene CE, McDermott M, Jameson PH, Atkins CL, Marks AM. Bartonella henselae infection in cats: evaluation during primary infection, treatment, and rechallenge infection. J Clin Microbiol 1996; 34: 1682–1685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Regnery RL, Rooney JA, Johnson AM, Nesby SL, Manzewitsch P, Beaver K, et al. Experimentally induced Bartonella henselae infections followed by challenge exposure and antimicrobial therapy in cats. Am J Vet Res 1996; 57: 1714. Erratum in: Am J Vet Res 1997 58: 803. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Kordick DL, Papich MG, Breitschwerdt EB. Efficacy of enrofloxacin or doxycycline for treatment of Bartonella henselae or Bartonella clarridgeiae infection in cats. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1997; 41: 2448–2455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Kaplan JE, Benson C, Holmes KH, Brooks JT, Pau A, Masur H, et al. Guidelines for prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in HIV-infected adults and adolescents: recommendations from CDC, the National Institute of Health, and the HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. MMWR Recomm Rep 2009; 58: 1–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Brunt J, Guptill L, Kordick DL, Kudrak S, Lappin MR. American Association Feline Practitioners 2006 Panel report on diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of Bartonella spp infections. J Feline Med Surg 2006; 8: 213–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]