Abstract

Practical relevance Optimising the clinical outcome for the cases we treat has to be of primary importance to every practitioner wherever they are working and whatever their sphere of practice, yet it requires much more than just clinical knowledge. This review discusses how a system of good clinical governance can help to achieve this goal. It focuses on clinical effectiveness, which in part involves the application of evidence-based veterinary medicine to formulate protocols or guidelines to help standardise and improve the quality of care given.

Benefits Once such guidance is in place, the measurement of clinical outcomes using the process of clinical audit can be of great assistance in ensuring that best practice is effectively applied. Both the theory and practical application of the so-called ‘clinical audit cycle’ within feline practice are illustrated in this review.

Prerequisites The use of such clinical management tools requires development of the necessary skills and protected time to apply them, but, as discussed, they can bring a broad range of benefits to the practice and its patients.

Clinical governance — the driving force

Clinical governance as a distinct entity has largely been developed within the UK's National Health Service (NHS), but it is a concept that any organisation providing health care, be it to humans or to cats, must surely aspire to (see left).

Clinical governance.

‘A framework through which (NHS) organisations are accountable for continually improving the quality of their services and safeguarding high standards of care by creating an environment in which excellence in clinical care will flourish.’ 1

In essence, clinical governance is a system for improving the standard of clinical practice. It is about looking at one's own practice, considering how it might be improved, and then implementing changes and finding out if those changes work. Ultimately, the aim is to create a ‘whole system’ culture that provides the organisation with the means to deliver sustainable, accountable, patient-focused, quality-assured clinical care.

Component processes

So, what does improving quality and ensuring that professionals are accountable for their practice necessitate? There is some variation in the precise detail, but broadly the processes include:

Risk management — including compliance with legal requirements (eg, health and safety legislation, control of substances hazardous to health regulations) and audit of critical events.

Human resource management — including building teams committed to improving the quality of care and a working environment in which problems can be openly discussed.

Client involvement — including effective communication of the evidence that helps clients to make informed decisions and avoid unrealistic expectations (Fig 1).

Use of information — including record keeping and evidence-based veterinary medicine.

Education, training and continuing professional development — the responsibility of professionals to keep up to date and to ensure the training of their staff.

Clinical effectiveness — the application of the best available knowledge, to achieve optimum outcomes for patients. Integral to this process is clinical audit (see later).

FIG 1.

Effective communication of the evidence base helps clients to make informed decisions and avoid unrealistic expectations

Clinical audit cycle.

‘The clinical audit cycle is a quality improvement process in clinical practice that seeks to establish guidelines for dealing with particular problems, based on documented evidence when it is available, measuring the effectiveness of these guidelines once they have been put into effect, and modifying them as appropriate. It should be an ongoing upwards spiral of appraisal and improvement.’ 4

A review in 2002 of the application of clinical governance to medical primary care concluded: ‘The experience of implementing clinical governance has been broadly positive to date.’ 3

Clinical effectiveness and clinical audit in context

Clinical effectiveness is a process whereby practices can systematically promote (and be seen to be promoting) good clinical care. Although defined in terms of patient care (see above), obviously in veterinary practice we need to consider the extra dimension of the requirements of the owner as well as the patient itself, and in some instances these may need to be balanced again one another.

Clinical audit is a method of measuring clinical effectiveness and, as such, is an important component. Of more practical relevance, though, is the ‘clinical audit cycle’ (see right), which is a means by which the measurement of clinical outcomes can be used to bring about an ongoing process of clinical improvement.

Clinical effectiveness — a medical definition.

‘The application of the best available knowledge, derived from research, clinical experience and patient preferences, to achieve optimum processes and outcomes of care for patients.’ 2

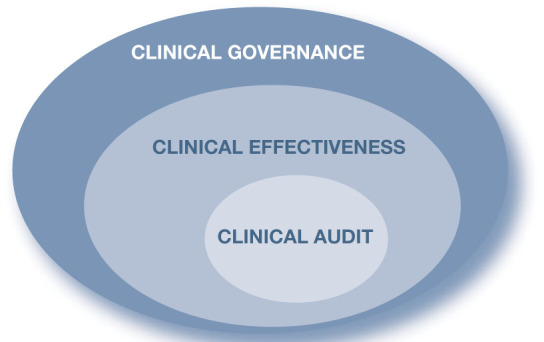

In simple terms, it is possible to think of clinical effectiveness as a major element of clinical governance, and in turn of clinical audit as one of the tools used to enhance clinical effectiveness (Fig 2).

FIG 2.

Clinical effectiveness is an important component of clinical governance and, in turn, incorporates clinical audit as a tool

Clinical effectiveness — what tools can the team use?

Improving clinical effectiveness requires a multifaceted approach to encourage excellence, and many different tools have been used including peer review, clinical incident review, surveys, benchmarking, clinical guidelines and the clinical audit cycle.

Peer review

Peer review involves an evaluation of the quality of care provided by a clinical team with a view to improving clinical care. Regular practice meetings to review interesting or unusual cases, and/or carry out morbidity and mortality assessments, are an example of how peer review can be incorporated into practice.

Critical incident review

A critical incident review is formalised peer review used in specific cases that have caused concern or for which there was an unexpected outcome (eg, an anaesthetic death in a patient that was considered to have been at low risk). Discussion and reflection should enable the team to learn from what has happened and to improve in future, but it is important that this can take place in a no-blame environment where all team members feel free to open up about what took place.

Client surveys and focus groups

Surveys and focus groups can be used to obtain users' views about the quality of care they have received and thus inform the manner in which clinical care is provided and the areas where there is most room for improvement.

Benchmarking

Benchmarking may be internal (ie, comparison within a practice or group), or external, involving comparison with similar practices or against an externally set ‘gold standard’. Benchmarks relating to postoperative complications in cats (and dogs) following routine neutering are now available to veterinary practitioners at www.vetaudit.co.uk.

Clinical guidelines — a convenient medium for the busy practitioner

Clinical guidelines can be defined as systematically developed statements to assist practitioner and client decisions about appropriate health care for patients in specific clinical circumstances and, therefore, enhance clinical effectiveness. The term ‘clinical protocol’ is sometimes used synonymously, although it can suggest a more rigid set of rules that the clinician is obliged to follow. In some instances, such as when the circumstances are very clearly defined and the consequences of not following specific instructions are potentially dire, the rigid application of protocols may be more appropriate than the assistance that guidelines can offer.

The use of clinical guidelines is extremely widespread in the medical profession around the world, as they are seen as having a number of benefits:

They can assist the application of evidence-based best practice to individual patients;

They help to provide a uniform standard of care;

They can be used in the education and training of health professionals;

They can help patients (clients) to make informed decisions by improving communications and managing expectations;

They can incorporate a cost/benefit analysis of diagnostic and treatment options.

Despite these advantages, medical clinical guidelines do have their antagonists. There are fears that they may be imposed by health authorities or medical insurance companies as cost-cutting exercises and thus restrict access to potentially useful treatments; that they may interfere with the clinical freedom of doctors; and, potentially, could be used against the medical profession in litigation and therefore increase defensive medicine.

Medical clinical guidelines are only one source of information available to the clinician, and are not suitable for every clinical situation. 5 In practice, they have not undermined the clinical judgement of doctors and, even where guidelines are laid down as a legal standard, courts still require sensible discretion to be used in applying them. 6

Examples of guidelines.

Currently few nationally developed clinical guidelines exist within the veterinary field, but feline practice is relatively well endowed.

A series of 26 protocols, written by the Feline Advisory Bureau's feline expert panel, and covering a wide range of clinical topics, such as anaemia, FLUTD, hyperthyroidism, blood pressure measurement and mycobacterial infections, is available from the International Society of Feline Medicine (www.isfm.net)

The European Advisory Board on Cat Diseases has issued guidelines on feline panleukopenia, feline herpesvirus infection, feline calicivirus infection, feline leukaemia (FeLV infection), feline immunodeficiency (FIV infection), feline infectious peritonitis, rabies, avian influenza, Chlamydophila felis and Bordetella bronchiseptica infections in cats. A synopsis of these was published in a special issue of this journal in July 2009. The main recommendations of the guidelines are also contained in a collection of fact sheets, available online in 18 languages at www.abcd-vets.org/factsheet/index.asp

The American Association of Feline Practitioners publishes guidelines for practice excellence, available at www.catvets.com/professionals/guidelines/publications. Among the subjects covered are feline life stages, senior care, zoonoses, feline behaviour, and retrovirus management and testing

Three key features differentiate guidelines from general clinical advice such as may be given in veterinary texts:

They involve an explicit attempt to systematically review the literature on the subject in question for the best available evidence.

They represent a consensus in the setting in which they are prepared, rather than the opinion of an individual. This may be a panel of experts if they are nationally developed guidelines, or a team of clinical staff if they are guidelines being written or adapted for local use.

The information is presented in summary form, often as a series of bullet points, so as to be readily accessible in a clinical situation.

Currently few nationally developed clinical guidelines exist within the veterinary field, but feline practice is actually relatively well endowed. Those, such as the International Society of Feline Medicine's (ISFM's) clinical protocols, the European Advisory Board on Cat Diseases' guidelines on infectious diseases and the American Association of Feline Practitioners' (AAFP's) guidelines (see box on page 563), as well as veterinary guidelines drawn up by the American Animal Hospital Association (www.aahanet.org/resources/guidelines.aspx), cover various aspects of feline/small animal medicine and practice. And in this very issue of J Feline Med Surg appears a new set of joint guidelines from the ISFM and AAFP on long-term NSAID use.

ISFM and AAFP consensus guidelines on long-term use of NSAIDs in cats.

Guidelines to encourage more widespread and appropriate use of NSAIDs in cats that would benefit from treatment are published on pages of 521–538 of this issue of J Feline Med Surg, and at: doi:10.1016/j.jfms.2010.05.004

While not the only way of communicating the findings of evidence-based veterinary medicine (EBVM), guidelines represent a convenient and accessible medium for the busy practitioner and are a useful starting point for practice discussion. It is likely that they will become more widely used in the veterinary profession in the future. Where guidelines are not already available, practitioners wishing to utilise them either independently or as part of the clinical audit process will often need to formulate them locally. In these instances, it falls upon the clinical team to follow the principles of EBVM.

EBVM and best practice

Evidence-based veterinary medicine is a discipline in its own right, and anyone with an interest in the subject is strongly advised to consult a dedicated text on the subject (eg, Cockcroft and Holmes' handbook). 7 The process of grading the evidence has previously been outlined in an editorial in this journal. 8 Within human medicine the best available knowledge has become synonymous with evidence based largely on randomised controlled trials, meta-analyses and systematic reviews. However, in veterinary practice we need to consider a broader range of evidence as these types of evidence are in short supply (see box above).

EBVM involves a five-stage process:

-

Convert information needs into answerable questions These may be about:

— The patient or problem being addressed;

— The intervention being considered;

— A comparison intervention (or control);

— The clinical outcome.

Track down the best evidence with which to answer them Evidence may be gathered from the clinical examination, diagnostic laboratory, published research or other sources.

Critically appraise the evidence How valid (close to the truth) and useful (clinically applicable) is it?

Apply the results of this appraisal to clinical practice.

Evaluate performance.

The aim is to establish what constitutes ‘best practice’ for the management of a particular condition under certain circumstances.

Best practice can be defined as the most efficient (involving the least amount of effort or expense) and effective (producing the best results) way of accomplishing a task.

Suitable for audit?

The areas of clinical veterinary practice that are most suited to being audited are:

Amenable to measurement

Commonly encountered

Have room for improvement in performance

Financially significant to the practice and/or animal owner

Best practice is often defined in terms of a local clinical setting where, in addition to any relevant evidence from research, the available skills and resources as well as individual clinician preferences are taken into account in delivering what is considered optimal for the patient in that context. As discussed earlier, best practice may be expressed in terms of a set of clinical guidelines for the condition in question. However, it is important to emphasise that any definition of best practice needs to be interpreted in the light of clinical experience in order to address the primary clinical concern of what is best for the patient at hand.

Clinical audit cycle — what is involved and what are the issues?

Clinical audit is the collecting and recording of clinical information with the aim of monitoring the quality of care. As purely a process of measurement it has limited value, although it can play a role in benchmarking the performance of one practice against another for the purposes of quality assurance. What is of potentially much more value is the clinical audit cycle, as defined earlier, because it can be used as a management tool to improve clinical performance.

A detailed explanation of the process is provided elsewhere. 9 For the purpose of this article, the key components of the clinical audit cycle — which are best visualised as a positive feedback loop (see below) — are:

-

Preparation — this includes:

— Selecting an area to audit;

— Considering your objectives for the audit;

— Making sure that you are able to record and retrieve information;

— Involving the team in the process, which includes developing a culture in which problems and differences of opinion can be freely discussed (Fig 4).

Establishing guidelines — see earlier.

Selection of criteria — these are ‘explicit statements that define what is being measured, and represent elements of care that can be measured objectively’. 10 Select criteria (which can be either outcomes or processes) that can be easily understood and measured, and set targets for each criterion.

-

Assessing the outcome and maintaining improvement

— Compare results with targets;

— Review and discuss how improvements could be made;

— Implement changes;

— Re-audit.

FIG 4.

Improving clinical effectiveness in practice requires developing a culture in which problems and differences of opinion can be freely discussed within the team

An example of the audit cycle being put into action is given on page 567.

Considerations for the practice

While carrying out clinical audit within the practice does not raise the same ethical dilemmas as practice-based research (Table 1), there are undoubtedly some barriers, as well as manifold benefits, to audit, as highlighted in the box on page 566. There are also a number of more general issues that warrant consideration, as outlined below.

TABLE 1.

Distinctions between audit and research

| Research | Clinical audit |

| Creates new knowledge | Tests care given against knowledge gained |

| Generally is based on a hypothesis | Measures against criteria |

| May involve ‘experiments’ on animals | Should never involve anything beyond clinical management |

| May need ‘ethical’ approval | Abides by an ethical framework but does not usually require ethical approval |

| May involve random allocation to different treatment groups, including placebo | Never involves random allocation or use of placebo |

| Usually carried out on a large scale over a prolonged period of time | Usually carried out on a relatively small number of cases over a short time span |

| Rigorous methodology — power calculations for sample sizes, statistical tests, etc | Different methodology from research; less need for large sample sizes and statistical significance |

| Results are generalisable and hence may be published; aimed at influencing the activities of clinical practice as a whole | Results are only relevant locally, influencing activities of local clinicians and teams; the audit process may be of wider interest and hence audits should still be published |

Clinical audit cycle.

Clinical audit does require an environment in which problems and departures from best practice can be freely discussed. In the past, the veterinary (and human) medical professions have shied away from the discussion of problems and the public may still not be ready to accept that performance in health care can be anything other than optimal. However ‘near miss’ reporting is now accepted practice in air traffic control, where problems are considered as a starting point for improving future performance. Therefore, to improve our clinical effectiveness it is necessary that we as a profession take an honest look at our performance and use problems as an opportunity to learn.

Research is concerned with discovering the right thing to do; audit with ensuring that it is done right. 11

Interpretation of audit data.

Statistical significance is important in a scientific experiment, which has to be designed with this in mind. A control group has to be formed; the numbers involved have to be large enough to be statistically significant; and ideally there will be some form of blinding to minimise bias. Trying to design an audit along these lines will usually result in failure and thus data that is generated by an audit should be viewed rather differently. If treated as scientific data, and the standard tests applied, it is usually very difficult to measure a statistically significant difference between outcomes before and after any changes were implemented. However, if the data are viewed as performance indicators, and investigated qualitatively in more depth where appropriate, they can be used as a logical basis for action. This is similar to using practice financial trends to guide commercial decisions. In other words, audit data cannot be ‘proven’ to be scientifically valid, and thus generalisable, but they can be used sensibly to guide our actions in an informed manner.

Audit — benefits and barriers.

Benefits of audit

Audit helps establish, firstly, what the practice is doing and, secondly, that what is being done is acceptable

It is a basis for improving clinical effectiveness

It improves job satisfaction

It helps standardise care throughout the practice

It increases public confidence in the profession as a whole and in individual practice procedures

It may fulfil the requirements of any national or local practice standard schemes

It assists in creating a positive culture within the clinical team

It is a management tool with the potential to increase practice income

If we don't do it, it might be imposed on us externally

Barriers to audit

Time — it takes time and effort to set up an audit

Manpower — staff may be taken away from other activities

Technology — while there is no reason why an audit cannot be done with pen and paper it is more frequently carried out using computerised data

Skills — lack of appropriate training

Fear — feeling of loss of control among clinical staff

Money — although there may also be cost/benefits (see text)

Avoiding pitfalls

Do not confuse audit with practice-based research

Pick a subject to audit that is relevant (ie, affects many/all and/or occurs commonly)

Clearly define the criteria

Do not overcomplicate the audit

Allow sufficient protected time

Case study.

Avonmore Veterinary Hospital has invested in equipment to measure blood pressure in cats, but after a few months it is apparent that very little use has been made of it, except as part of the senior pet profile that is offered to owners. The head veterinarian decides that the best way to encourage utilisation of what he considers to be a clinically important tool is to bring together a team of key players and undertake a clinical audit.

The audit process The team, consisting of the practice head nurse, front desk manager and two other veterinarians, agrees that screening for hypertension is a suitable area to audit because it is important, common, and the practice has plenty of room to improve its performance. They discuss various approaches to the issue and decide that a simple process of audit, evaluating the number of blood pressure measurements carried out over a period of time, will suffice, but that they will limit the inclusion criteria to cats that are considered to be at high risk. They agree to go away and examine the evidence base for measuring blood pressure in older cats and which groups are most at risk.

When they reconvene they agree that the audit will be restricted to cats suffering from one of three conditions: chronic nephritis, hyperthyroidism or cardiomyopathy. They also agree that they will use the evidence they have gathered to draw up information sheets for clients, stressing the importance of regular blood pressure monitoring for at-risk cats, and guidelines for the practice team, outlining how such cases should be handled. There is a discussion as to whether the criterion to be measured should be the number of animals that have their blood pressure measured, or simply the number of blood pressure measurements performed, over a period of time. As it is a simple matter to pull out the product ‘blood pressure measurement’ using the practice management software, it is decided simply to measure any increase in the absolute numbers being performed over a 2-month period.

What is identified? The group meets again after the audit period has elapsed to consider the results. Over the 2 months before the audit started they had only carried out six blood pressure measurements, compared with 22 during the audit period. The group feels this is a heartening increase, but in view of the fact that there were 72 cats in the practice diagnosed with one of the three qualifying conditions, they consider there is plenty of room for further improvement. After discussing the barriers to concordance with the vets' recommendations, they decide there is a need for better awareness of what is being done internally via a series of practice meetings, including the front desk staff, who are recognised as having an important role in translating a veterinary recommendation into a booking for a procedure. It is also decided to send written advice to owners of all relevant cats reinforcing the need for regular monitoring of blood pressure and stressing the sudden and severe consequences, such as blindness and sudden hind limb paralysis, that could result if it went undiagnosed.

What next? A meeting after a second 2-month audit period reveals a further increase in the number of blood pressure measurements being charged, from 22 to 51. This is considered to be very satisfactory — the extra income from the procedures carried out more than compensating for the time and effort involved. The group decides that it will carry out a data search to examine the individual records of cats that had not had their blood pressure checked to see if there are particular reasons why they should have been excluded. It is agreed to carry on for another 2-month audit period. The group also decides that it will carry out an outcome audit, measuring the blood pressure of hypertensive cats 4 months after diagnosis, to see how well their condition is being controlled.

Within the practice, preparation for an audit, including the production of guidelines, should provide the opportunity for discussion of different viewpoints and a review of the evidence. This is within the context that individual clinicians remain responsible for the clinical care of their patients and are required to exercise judgement in their application.

The aim of clinical audit is to improve clinical effectiveness throughout the practice, but the audit data that is gathered may potentially reveal significant differences between individual clinicians. Some thought should be given as to how the issues raised by this will be handled.

And what if results of an audit reveal failure to achieve targets for best practice? While there are few ethical problems with trying to improve performance, there may be ethical implications in continuing to follow procedures that fail to meet expected targets.

There may also be issues about how collected data should be used. The lack of statistical significance of clinical audit data has already been mentioned, and extreme care should be taken in drawing comparisons between practices on the basis of audit. There may be benefits to the profession in organised collation of clinical audit data, to enable practices to benchmark their own performance, but this will raise issues of confidentiality and the possibility of ‘league tables’ being created that compare practices. Great care then needs to be taken to ensure that like is compared with like.

KEY POINTS.

Clinical governance provides a framework to help improve standards of clinical care.

Clinical guidelines can assist in applying evidence-based veterinary medicine uniformly but need to be used flexibly with the needs of the individual patient in mind.

Research answers the question ‘what is best practice?’; clinical audit establishes if it is being put into effect.

Clinical audit can bring many benefits apart from improved clinical outcomes, including enhanced team working, job satisfaction and increased income, but needs the development of the relevant skills and adequate resourcing.

References

- 1. Scally G, Donaldson LJ. Clinical governance and the drive for quality improvement in the new NHS in England. Br Med J 1998; 317: 61–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. RCN. Clinical effectiveness strategy. Clinical effectiveness steering group report, 1996.

- 3. Campbell SM, Sweeney GM.The role of clinical governance as a strategy for quality improvement in primary care. Brit J Gen Pract 2002; 52 (suppl): S12–S18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Viner B. Using audit to improve clinical effectiveness. In Pract 2009; 31: 240–43. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hewitt-Taylor J. Clinical guidelines and care protocols. Chichester: John Wiley and Sons, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hurwitz B. Clinical guidelines: legal and political considerations of clinical guidelines. Br Med J 1999; 318: 661–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cockcroft P, Holmes M. Handbook of evidence based veterinary medicine. Oxford; Blackwell Publishing, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lloret A. The process of evidence-based medicine. J Feline Med Surg 2009; 11: 529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Viner B. Success in veterinary practice: maximising clinical outcomes and personal well-being. Chichester; Wiley-Blackwell, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 10. National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Principles for ‘best practice’ in clinical audit. Oxford: Radcliffe Medical Press, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Smith R. Audit and research. Br Med J 1992; 305: 905–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]