Abstract

Objectives

We evaluated the efficacy of cryosurgery in association with itraconazole for the treatment of feline sporotrichosis. We also compared the length of treatment protocol with others reported in the literature.

Methods

Cats naturally infected with fungi of the Sporothrix schenckii complex were evaluated. Diagnosis was confirmed by cytology and fungal culture. Prior to the cryosurgical procedure, every animal was receiving itraconazole 10 mg/kg/day PO, for different time periods. The same protocol was maintained until 4 weeks after complete healing of the lesions.

Results

Eleven of 13 cats were considered clinically cured. The treatment duration ranged from 14–64 weeks (median 32 weeks).

Conclusions and relevance

The combination of cryosurgery and itraconazole was effective in treating cases of feline sporotrichosis and decreased the treatment length compared with protocols using only medication.

Introduction

Sporothrix schenckii species complex is the etiological agent of sporotrichosis, a subcutaneous mycosis of humans and other mammals. It has a worldwide distribution but is more common in tropical and subtropical countries. The cat is the animal species most affected by this fungal infection and has a great zoonotic potential. 1 Feline clinical cases are associated with multiple skin lesions, and, less often, respiratory disease and fatal systemic involvement. Subcutaneous nodules and ulcers are the most frequent lesions in diseased cats. 2

Treatment of feline sporotrichosis is a challenge for veterinarians. Azoles and iodides are commonly used medications; however, cure, therapeutic failure and adverse effects occur regardless of the employed protocol.3,4 The need for regular and extended treatment, combined with the cost and the trouble of giving cats medication, are contributing factors to the low percentage of clinical cure. 5

We evaluated the efficacy of cryosurgery in association with itraconazole for the treatment of feline sporotrichosis. We also compared the length of treatment protocol with others reported in the literature.

Materials and methods

Inclusion criteria

Between 2003 and 2013, cats were examined in three veterinary hospitals, one each in the cities of Rio de Janeiro, Seropédica and São Paulo, Brazil.

Cats with skin lesions by naturally acquired sporotrichosis with no systemic signs of the infection were included in the study.

Prior to the cryosurgical procedure, every animal was receiving itraconazole 10 mg/kg/day, orally, for different time periods.

S schenckii complex fungi was first diagnosed in each cat through cytology and culture. On the day of the cryosurgery, another sample of skin lesion was collected through biopsy and sent for tissue culture to confirm Sporothrix infection.

Cryosurgical technique

A cryosurgical protocol was applied to each animal as previously reported for different canine and feline dermatoses. 6

Every cat was premedicated with acepromazine; then, anesthesia was induced with propofol, and maintained with halothane or isoflurane during the cryosurgery procedure.

Lesions were frozen by liquid nitrogen spray (Cry-ac-3; Brymill Criogenic Systems). Lesions ⩿5 cm diameter were frozen using a small aperture tip (C), while a larger aperture (B) was used for lesions >5 cm. Liquid nitrogen was applied from a distance of 2–3 cm from the target tissue until a frozen halo around the lesion was achieved. Three freeze–thaw cycles were applied to every lesion. After the first cycle, the following cycles were performed after complete thaw of the preceding freeze. Thaw time was determined by the disappearance of the ice halo.

For postprocedural care, cats with nasal involvement were treated with tramadol 2–4 mg/kg q8h for 5–7 days. When the nose was not affected, cats were medicated with metamizole 25 mg/kg q12h for 5–7 days. Owners were instructed to clean the wounds with saline solution and gauze if they notice any kind of discharge from the lesions.

Animals were rechecked every 2 weeks after the cryosurgery procedure.

Antifungal treatment

Prior to the cryosurgical procedure, every animal was receiving itraconazole 10 mg/kg/day for various time periods. After cryosurgery, the administration of medication was maintained at the same dose of 10 mg/kg/day until 4 weeks after lesions were completely healed. Then, cats were considered clinically cured.

Results

Infected cats were all domestic shorthairs of both sexes and various ages, and had different durations of infection. The cats were client-owned animals, but 12 of them roamed freely in their neighborhoods, allowing contact with other cats and other potential sources of infection. Previous life records of two animals (cats 7 and 9) were incomplete because they were rescued when already infected with sporotrichosis. The medical records from these two cats were current since the first day they started taking itraconazole (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of 13 evaluated cats with sporotrichosis

| Cat | Sex | Housing | Age at emergence of skin lesions caused by Sporothrix (months) | Age at time of cryosurgery (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Male | Indoors/outdoors | 23 | 24 |

| 2 | Male | Indoors/outdoors | 60 | 72 |

| 3 | Male | Indoors/outdoors | 114 | 120 |

| 4 | Female | Indoors/outdoors | 30 | 36 |

| 5 | Male | Indoors/outdoors | 25 | 30 |

| 6 | Female | Indoors/outdoors | 2 | 16 |

| 7 | Female | Indoors/outdoors | NR | NR |

| 8 | Male | Indoors | 5 | 8 |

| 9 | Female | Indoors/outdoors | NR | NR |

| 10 | Male | Indoors/outdoors | 20 | 24 |

| 11 | Female | Outdoors | 110 | 122 |

| 12 | Female | Outdoors | 50 | 62 |

| 13 | Male | Outdoors | 72 | 84 |

NR = not reported

Evaluated cats had several lesions, mostly ulcerated, on different areas of the body and of varying size (Table 2; Figures 1–3).

Table 2.

Morphological aspects and location of lesions on cats at the time of the cryosurgical procedure

| Cat | Lesion pattern | Greater lesion diameter (cm) | Lesion location |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ulcer | ⩿5 | Right hindlimb, face |

| 2 | Ulcer | ⩿5 | Left ear pinna, cervical region, dorsolumbar, right hindlimb |

| 3 | Ulcer | ⩿5 | Bottom of ears |

| 4 | Ulcer | >5 | Temporal region, dorsal neck |

| 5 | Ulcer | ⩿5 | Both ear pinnae, nasal planum, left forelimb |

| 6 | Ulcer | ⩿5 | Nasal planum |

| 7 | Ulcer | >5 | Nasal bridge |

| 8 | Ulcerated nodule | ⩿5 | Left ear pinna, nasal bridge |

| 9 | Ulcer | >5 | Both ear pinnae, right and left forelimbs, right and left hindlimbs |

| 10 | Ulcer | >5 | Face, both ear pinnae, right and left forelimbs, right and left hindlimbs |

| 11 | Ulcerated nodule | ⩿5 | Lateral thorax, right hindlimb |

| 12 | Nodule | ⩿5 | Temporal region |

| 13 | Ulcerated nodule | ⩿5 | Nasal planum, both ear pinnae |

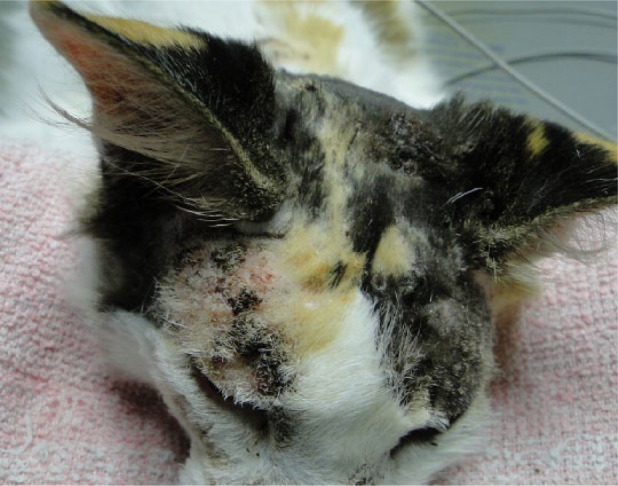

Figure 1.

Ulcerated lesions on nasal bridge and part of nasal planum of cat 7. Before cryosurgery, punch biopsy samples of the lesions were collected for histopathology and culture

Figure 2.

Ulcerated lesion on nasal bridge of cat 7 undergoing a freeze–thaw cycle of cryosurgery

Figure 3.

Ulcers and crusts on head (temporal region and between ears) of cat 4 on the day of cryosurgery

Among the 13 studied cats, 11 were considered clinically cured. Treatment length ranged from 14–64 weeks (median 32 weeks), starting from the beginning of itraconazole administration until discontinuation 4 weeks after resolution (Table 3).

Table 3.

Results and duration of treatment, and follow-up, in 13 cats receiving itraconazole 10 mg/kg/day in association with cryosurgery for the management of sporotrichosis

| Cat | Preliminary itraconazole treatment (weeks) | Length of itraconazole treatment after cryosurgery (weeks) | Result of treatment protocol (itraconazole + cryosurgery) | Duration of treatment until clinical cure (weeks) | Duration of follow-up after clinical cure (weeks) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 12 | Clinical cure | 14 | 40 |

| 2 | 8 | 20 | Clinical cure | 28 | 96 |

| 3 | 2 | 12 | Clinical cure | 14 | 240 |

| 4 | 6 | 28 | Clinical cure | 34 | 48 |

| 5 | 20 | 16 | Clinical cure | 36 | 40 |

| 6 | 56 | 8 | Clinical cure | 64 | 72 |

| 7 | 2 | 28 | Clinical cure | 30 | 24 |

| 8 | 12 | 48 | Failure | – | – |

| 9 | 12 | 4 | Failure | – | – |

| 10 | 3 | 20 | Clinical cure | 23 | 32 |

| 11 | 24 | 24 | Clinical cure | 48 | 56 |

| 12 | 16 | 24 | Clinical cure | 40 | 40 |

| 13 | 24 | 8 | Clinical cure | 32 | 48 |

After clinical cure, the cats were followed up through clinical rechecks, telephone contact or through pictures sent electronically by the owners, for time periods ranging from 24–240 weeks. During this evaluation period none of the cured animals relapsed (Table 3; Figures 4–7).

Figure 4.

Crusts on nasal bridge of cat 7, 5 days after cryosurgery on sporotrichosis-associated lesions

Figure 5.

Fibrotic area on nasal bridge and part of nasal planum of cat 7 during healing process, 19 weeks after cryosurgery

Figure 6.

Crusts on head of cat 4, 16 days after cryosurgery on sporotrichosis-associated lesions

Figure 7.

Cicatricial area on head of cat 4, 18 weeks after cryosurgery

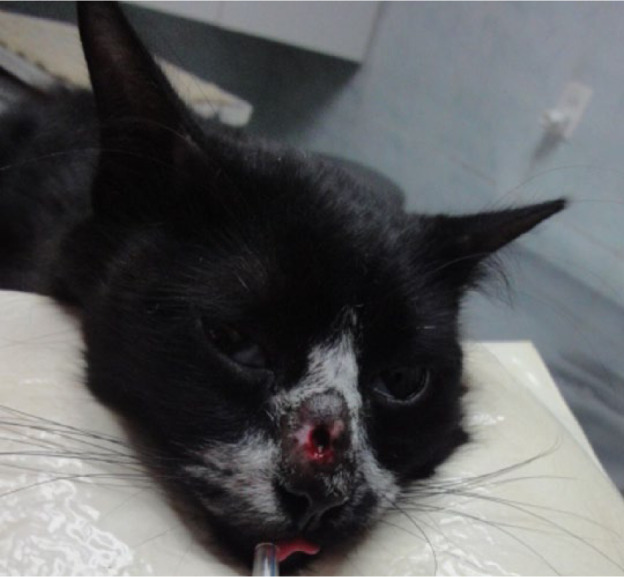

The combination of cryosurgery and itraconazole did not achieve good results over lesions of two animals (cats 8 and 9), and therapeutic failure was considered for both (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Ulcerated lesion on nasal bridge of cat 8, 48 weeks after cryosurgery when therapeutic failure was established

Discussion

Cryosurgery is the use of cold with therapeutic purposes. This technique involves the freezing of biological tissues leading to their destruction. It is indicated for the treatment of non-responsive neoplastic, inflammatory and degenerative diseases. 6 To our knowledge, this is the first report in veterinary medicine evaluating the use of itraconazole plus cryosurgery for the treatment of cutaneous sporotrichosis. Similarly, a study on the treatment of sporotrichosis in humans using liquid nitrogen showed good results. 7 A number of infected patients do not tolerate orally prescribed drugs, making physicians look for treatment alternatives. They justify the choice for cryosurgery, explaining that all live organisms are sensitive to extreme temperatures, both high and low, causing the death of the pathogen. 7 It has been previously described that surgical resection, in combination with antifungal treatment, can also be healing, either for humans or cats with sporotrichosis, as long as the lesion is located on anatomically and physiologically accessible areas. According to the literature, the feline nasal region is not easily accessible for surgical procedures, hindering the cure of nasal infections. 5 Among the studied animals, five presented with lesions on the nasal region (cats 5, 6, 7, 8 and 13), and four achieved clinical cure with the protocol of itraconazole in association with cryosurgery.

Itraconazole is considered the drug of choice for treating sporotrichosis in cats and has been proven to be effective, but clinical response can be unsatisfactory in some cases, especially in those with respiratory signs and nasal mucosa lesions. 4 The choice of cryosurgery as an alternative option for treating feline sporotrichosis, combined with the standard antifungal protocol, had the purpose of optimizing treatment. We aimed to decrease the length until clinical cure to minimize costs, avoid common adverse effects related to itraconazole, such as vomiting and loss of appetite, and increase owners’ compliance with the treatment of cats.

An epidemiologic study evaluated therapeutic protocols with different drugs, where clinical cure was achieved in 25.6% of the cats, and treatment length ranged from 16–80 weeks (median 36 weeks). 8 In this study, the authors followed up 266 cats and, among the 68 clinically cured, 33.8% used itraconazole with a dose of 5–10 mg/kg/day. Despite the difference in number of cats evaluated in the present study, it can be suggested that the association of itraconazole with cryosurgery achieved a better percentage of clinical cure (84.6%) in a shorter period of time.

Another study conducted with 773 cats comparing the use of ketoconazole and itraconazole applied higher doses of both drugs than those usually used to treat feline sporotrichosis because of the difficulty in achieving clinical cure. For the cats under the ketoconazole protocol (doses of 13.5–27.0 mg/kg/day), a cure rate of 28.6% was observed with a median treatment time of 28 weeks (range 8–170 weeks). However, 42% presented with gastrointestinal adverse events, such as hyporexia, vomiting and/or diarrhea, likely related to drug administration. For the group of cats receiving itraconazole (doses of 8.3–27.7 mg/kg/day), 38.3% achieved complete resolution of clinical signs with a median treatment time of 26 weeks (range 8–131 weeks); however, 30.9% of them also experienced adverse effects. 4 If animals tolerate high doses of azoles until clinical cure, especially if costs are not an issue for the owners, these protocols could be an option.

Iodides are also commonly used medications for the treatment of Sporothrix infection, and potassium iodide can be an alternative for refractory cases to oral itraconazole. Few studies have been carried out using iodide in saturated solution for cats, and the results are inconclusive. Some studies reported clinical cure, even though others stated that the treatment was unsuccessful.9–11 A recent study described a large case series using potassium iodide capsules for the treatment of cats with skin lesions and respiratory signs of sporotrichosis. The authors applied a protocol of progressively increasing doses according to clinical responses and signals of toxicity, starting from 2.5 mg/kg/day and increasing to 20 mg/kg/day. Clinical cure was achieved in 47.9% of patients with a treatment period ranging from 4–5 months. Hyporexia and a mild increase in liver enzyme levels were observed in some animals during the treatment. 9

As these results were published after the end of the present trial, the use of potassium iodide capsules was not considered as an alternative instead of cryosurgery. Potassium iodide saturated solution was not applied because its concurrent usage with itraconazole needs to be investigated further.

Intralesional application of amphotericin B in cats has been reported as an option for treating residual localized lesions of sporotrichosis refractory to itraconazole. A study showed good results, with the number of applications ranging from 1–5 weekly or every other week. 12 However, the requirement of sedation every time it is applied can be an issue for some animals and owners. Moreover, its purchase is extremely limited in Brazil, and was not considered in the current study.

Extracutaneous clinical signs of feline sporotrichosis, mainly respiratory, are often observed in infected animals. However, cats in this study did not show any disorders but the skin lesions caused by Sporothrix. This condition allowed them to be anesthetized for the cryosurgical procedure. This may also have contributed to the high percentage of success because the presence of extracutaneous signs can be inversely associated to clinical cure and directly related to death, with the risk being twice as high. 3

Cat 8 received daily oral itraconazole for 48 weeks after cryosurgery, but no clinical resolution was observed. At that time, cytological examination of the lesion still showed fungal structures compatible with S schenckii. The treatment failure of cat 8 may be attributable to an undetermined immunosuppressive cause. Despite being in good general condition and not displaying any clinical signs of other concurrent disease, several tests were carried out, including complete blood count, serum biochemistry to evaluate liver and kidney enzymes, feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV) and feline leukemia virus (FeLV) serological tests, abdominal ultrasound and thoracic radiographs, all of which presented normal or negative results. However, recent studies with both humans and cats indicate that the clinical evolution and treatment response of sporotrichosis are not associated with patient immune status.4,8,13 Coinfection of sporotrichosis and FIV and FeLV viruses in cats did not show significant difference in treatment outcome in comparison with animals without virus infection. 8

After 48 weeks of treatment, cat 8 was referred for another cryosurgical procedure (Figure 5). A low dose of potassium iodide-saturated solution was also added to the therapeutic protocol. In accordance with the goal of this study, at this time treatment failure had already been established and follow-up for this cat was done separately.

Cat 9 did not show any remarkable improvement in lesion healing 4 weeks after cryosurgery and her owner requested euthanasia. Treatment withdrawal is frequently encountered because of the difficulty of giving oral drugs to cats, the high cost of medications, the long treatment length and also the fear of acquiring the infection. 3

The existence of endemic areas of human and animal sporotrichosis, as well as the difficulty in treating felines, justify the search for effective and safe therapeutic protocols for the treatment of this fungal infection. The combination of cryosurgery and itraconazole could be indicated immediately upon diagnosis of sporotrichosis or anytime during antifungal treatment to shorten therapy length and take advantage of its associated benefits.

Conclusions

The association of cryosurgery and itraconazole was effective for the treatment of feline sporotrichosis, and it reduced the average treatment time.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Lindsey Mathews and Mr Kenneth Hampton for proofreading the manuscript prior to submission.

Footnotes

The authors do not have any potential conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Accepted: 8 February 2015

References

- 1. López-Romero E, Reyes-Montes MR, Pérez-Torres A, et al. Sporothrix schenckii complex and sporotrichosis, an emerging health problem. Future Microbiol 2011; 6: 85–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pereira SA, Menezes RC, Gremião IDF, et al. Sensitivity of cytopathological examination in the diagnosis of feline sporothricosis. J Feline Med Surg 2011; 13: 220–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pereira SA, Schubach TMP, Gremião IDF, et al. Aspectos terapêuticos da esporotricose felina. Acta Sci Vet 2009; 37: 311–321. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pereira SA, Passos SRL, Silva JN, et al. Response to azolic antifungal agents for treating feline sporotrichosis. Vet Rec 2010; 166: 290–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gremião IDF, Pereira SA, Rodrigues AM, et al. Tratamento cirúrgico associado à terapia antifúngica convencional na esporotricose felina. Acta Sci Vet 2006; 34: 221–223. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lucas R. Crioterapia na clínica veterinária: avaliação da praticabilidade, exequibilidade e efetividade em dermatoses de caninos e felinos. MS thesis, University of São Paulo, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bargman H. Successful treatment of cutaneous sporotrichosis with liquid nitrogen: report of three cases. Mycoses 1995; 38: 285–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Schubach TMP, Schubach A, Okamoto T, et al. Evaluation of an epidemic of sporothricosis in cats: 347 cases (1998–2001). J Am Vet Med Assoc 2004; 224: 1623–1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Reis EG, Gremião IDF, Kitada AAB, et al. Potassium iodide capsule treatment of feline sporotrichosis. J Feline Med Surg 2013; 14: 399–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gonzalez Cabo JF, de las Heras Guillamon M, Latre Cequiel MV. Feline sporotrichosis: a case report. Mycopathologia 1989; 108: 149–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mackay BM, Menrath VH, Ridley MF, et al. Sporotrichosis in a cat. Aust Vet Pract 1986; 16: 3–5. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gremião IDF, Schubach TMP, Pereira SA, et al. Treatment of refractory feline sporotrichosis with a combination of intralesional amphotericin B and oral itraconazole. Aust Vet J 2011; 89: 346–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Freitas DFS, Hoagland BS, Valle ACF, et al. Sporothichosis in HIV-infected patients: report of 21 cases of endemic sporotrichosis in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Med Mycol 2012; 50: 170–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]